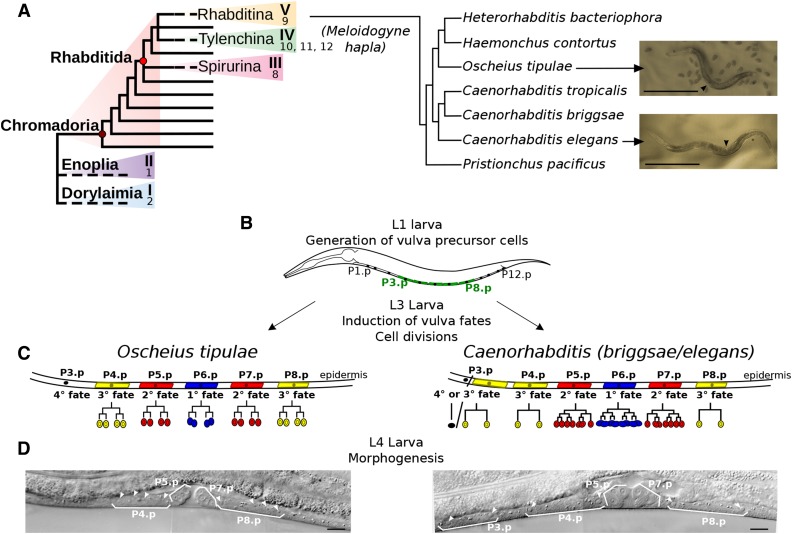

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships of O. tipulae and comparison of vulva development with C. elegans. (A) Cartoons showing (left) the systematic structure phylum Nematoda [clades I–V or 1–12 defined according to Blaxter et al. (1998), p. 199, and van Megen et al. (2009), respectively] and (right) the relationship of O. tipulae to key Rhabditina species discussed in the text. Pictures of young adult hermaphrodites of O. tipulae and C. elegans are shown on the right (arrowhead pointing to the vulva). Bar, 0.5 mm. (B–D) Vulva development in O. tipuale and C. elegans. (B) Ventral epidermal cells called P3.p to P8.p are specified as vulva precursor cells in young L1 larvae. (C) Conserved anteroposterior pattern of cell fates, despite variation in cell lineages: P6.p occupies the central position and adopts a 1° fate, P5.p and P7.p are induced to follow a 2° fate, and their daughters will form the border of the vulval invagination. Other cells (P3,4,8.p) differentiate into nonvulval epidermal fates, either with or without one round of division (3° or 4° fates, respectively). (D) Nomarski images of wild-type, L4-stage hermaphrodites (left, O. tipulae; right, C. elegans), highlighting the daughter cells of the Pn.p cells (arrowheads). Bar, 10 µm.