Abstract

Despite limited pharmacokinetic (PK) data, dexmedetomidine is increasingly being used off-label for sedation in infants. We aimed to characterize the developmental PK changes of dexmedetomidine during infancy. In this open-label, single-center PK study of dexmedetomidine in infants receiving dexmedetomidine per clinical care, ≤10 blood samples per infant were collected. A set of structural PK models and residual error models were explored using nonlinear mixed effects modeling in NONMEM. Covariates including postmenstrual age (PMA), serum creatinine, and recent history of cardiac surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass were investigated for their influence on PK parameters. Univariable generalized estimating equation models were used to evaluate the association of hypotension with dexmedetomidine concentrations. 89 PK samples were collected from 20 infants with a median PMA of 44 weeks (range, 33–61). The median maximum dexmedetomidine infusion dose during the study period was 1.8 μg/kg/hr (0.5–2.5), and 16/20 infants had a maximum dose >1 μg/kg/hr. A one-compartment model best described the data. Younger PMA was a significant predictor of lower clearance. Infants with a history of cardiac surgery had ~40% lower clearance compared to those without a history of cardiac surgery. For infants with PMA of 33–61 weeks and body weight of 2–6 kg, the estimated clearance and volume of distribution were 0.87–2.65 L/kg/h and 1.5 L/kg, respectively. No significant associations were found between dexmedetomidine concentrations and hypotension. Infants with younger PMA and recent cardiac surgery may require relatively lower doses of dexmedetomidine to achieve exposure similar to older patients and those without cardiac surgery.

Keywords: Precedex, neonate, PK, population pharmacokinetics

Introduction

Over 90% of infants hospitalized in the intensive care unit (ICU) undergo multiple painful procedures.1 Pain and resulting agitation are associated with increased morbidity in infants, including hemodynamic instability, pathologic stress responses, and inadequate ventilation, which places infants at risk for lung injury.2 Thus, there is a critical need for safe and effective means of achieving pain control and sedation in the ICU. The most commonly used drugs for this purpose are opioids and benzodiazepines.3 However, these drugs are frequently associated with severe side effects including respiratory depression, hypotension, delayed gastric motility, and adverse neurologic events.4–6 In addition to causing increased morbidity and mortality, these side effects can lead to increased length of stay in the ICU and increased cost of care.

Dexmedetomidine represents an alternative treatment for pain and agitation. Dexmedetomidine is a selective central α2-adrenergic agonist that is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in adults for ICU and procedural sedation.7 Studies of dexmedetomidine in children are limited, and the drug is not FDA-approved for children. However, the safe and effective use of dexmedetomidine in adults has led physicians to prescribe the drug off-label in children. In safety and efficacy trials in older children, dexmedetomidine has been shown to be an effective sedating agent with few adverse side effects.8,9 Experience with dexmedetomidine in infants is limited to case reports and small case series.10–15

Understanding the pharmacokinetics (PK) of a drug is essential to determining a safe and effective dose in infants, whose drug disposition and metabolism differ markedly from older children and adults.16 In adults, dexmedetomidine undergoes almost complete biotransformation via extensive hepatic metabolism that involves both direct glucuronidation as well as cytochrome P450 mediated metabolism, with most of the metabolites excreted in the urine.7 Although the PK of dexmedetomidine is well-described in adults, there is insufficient PK data to inform dosing of this drug in infants. To date, 6 PK studies have been performed in children, and only one of these studies evaluated infants alone.17–22 Doses of dexmedetomidine in these studies ranged between 0.05–1 μg/kg (loading dose) and 0.55–0.75 μg/kg/hr (continuous infusion rate), although higher doses in infants have been reported without PK data.10,11,14 The PK studies have generally shown a larger volume of distribution for children compared to adults, reduced clearance in the first year of life, and significant inter-individual variability for the PK parameters. Further studies of dexmedetomidine PK in infants are needed. The goal of the current study was to use novel approaches including opportunistic methodologies and population PK to further define the PK of dexmedetomidine in infants.

Methods

The Duke University Institutional Review Board provided approval for the study with informed consent by each participating infant’s parent or legal guardian.

Study Design

We performed an open-label PK study of dexmedetomidine. Infants <12 months of age receiving dexmedetomidine (concentration 4 μg/mL; Precedex™, Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL) as part of standard of care in the Duke University Medical Center Intensive Care Nursery, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, or Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Unit were eligible for the study. All infants received dexmedetomidine continuous intravenous infusions at the time of enrollment, and some infants received additional bolus intravenous injections as loading doses or supplemental bolus doses.

Study Procedures

Demographic data, clinical data (including concomitant sedating or paralyzing medications within 24 hours of PK sample, diagnoses, procedures, and laboratory values), and dexmedetomidine dosing information were collected prospectively from medical records. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at Duke University.23 Blood samples obtained were 0.2 mL in volume, and a maximum of 10 blood samples were obtained per infant. When possible, blood samples were collected when labs were being obtained per standard of care; however, the infant’s guardian was given the option to consent for additional blood sample collection.

Biologic Sample Analysis

Concentrations of dexmedetomidine in plasma were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) after solid phase extraction (University of Turku, Finland). Calibration standards and quality control samples were prepared in drug-free human ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) plasma. The linear concentration range of dexmedetomidine (base form) was from 0.02 ng/ml to 5.0 ng/ml. The lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) was 0.05 ng/ml. Samples below the LLOQ were excluded from the analysis. The intra-assay accuracies of the quality control samples (0.06, 0.15, 1.0 and 4.0 ng/ml) ranged from 98.5 to 108.1%.

PK Analysis

The primary outcome of the study was the PK of dexmedetomidine. The dosing, sampling, and demographic information were merged with the bioanalytical information to create a PK dataset. Data were analyzed using nonlinear mixed effects modeling with NONMEM 7 software (version 7.2, Icon Solutions, Ellicott City, MD) and the first order conditional estimation with interaction algorithm. One- and two-compartment structural PK models and proportional, additive, and proportional plus additive residual error models were explored. Size was included by allometric scaling a priori as a covariate for structural model parameters.24 The allometric exponent for weight on clearance was fixed to be 0.75 (WT0.75). The allometric exponent for weight on volume was fixed to be 1 (WT1.0). Estimation of the allometric exponents for weight on clearance and volume of distribution was also explored. Data formatting and visualization were performed using Stata (version 13.1, College Station, TX), R (version 3.0.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and RStudio (version 0.97.551, RStudio, Boston, MA) software, including lattice, Xpose and ggplot2 packages.

Model Building Steps

Once the base model was identified, covariates were investigated for their influence on PK parameters. Continuous covariates evaluated were postmenstrual age (PMA), postnatal age, and serum creatinine. Categorical covariates included cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass within 48 hours of sampling and sex. Individual participant etas (η), defined as the deviation from the typical population parameter values, were plotted against covariates to graphically assess relationships between variability in PK parameters and covariates. In addition to a power model, the relationship between PMA and CL was explored using a sigmoidal Emax maturation function (FPMA), where FPMA = PMAHILL/(TM50HILL + PMAHILL); FPMA denotes the fraction of the adult clearance value; TM50 represents the value of PMA (weeks) when 50% adult clearance is reached; and HILL is a slope parameter for the sigmoidal maturation model. Covariates with a discernible graphical relationship to etas were evaluated for inclusion in the final model. During the model building process, potential covariates that reduced the objective function by more than 3.84 (p <~0.05) were planned for inclusion in the subsequent multivariable analysis. A forward-addition, backward-elimination approach to covariate selection was planned for use if more than one covariate were found to be significant, and a reduction of 6.6 (p <~0.01) was required for retention of a covariate in the final model.

Model Evaluation

Diagnostic plots included the following: observed versus population predicted concentration and versus individual predicted concentration; conditional weighted residuals versus predicted concentration and versus time after dose; random effects and conditional weighted residuals histograms; and observed versus predicted and individual predicted concentrations by infant. Diagnostic plots, parameter precision, and objective function value (OFV) were used to assess model goodness of fit.

The final model was evaluated using standardized visual predictive check. In this evaluation, the final model was used to generate 1000 Monte Carlo simulation replicates per time point of dexmedetomidine exposure. Simulated results were compared at the participant level with those observed in the study by calculating and plotting the percentile of each observed concentration in relation to its 1000 simulated observations derived from the final model.25 The dosing and covariate values used to generate the predictions in the standardized visual predictive check were the same as those used in the study population. The number of observed concentrations outside of the 80% prediction interval for each time point was quantified. In addition, a traditional visual predictive check was performed to verify the model predictions of the central tendency and variability. Nonparametric bootstrapping (1000 replicates) was performed to evaluate the precision of the final population PK model parameter estimates and to generate the 95% confidence intervals for parameter estimates.

Exposure-Response Relationship

Although the primary objective of our study was to evaluate the PK of dexmedetomidine, we also collected clinical data related to safety and efficacy. Events were captured if they occurred during the study period, which was defined from the time of informed consent until the final PK sample was obtained. To determine whether drug concentration was associated with safety, we recorded the incidence of events during the study period including hypotension requiring vasopressors, skin reactions, death, and any other adverse events that were considered by the treating clinician to be related to dexmedetomidine. We compared the overall average concentrations to the predicted concentrations at the time of hypotension using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. We compared the overall maximum drug concentration values among infants who died and did not die using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Data manipulation, data visualization, and non-PK statistical analysis were performed using Stata (version 14.1, College Station, TX).

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 20 infants were enrolled in the study (Table 1). The median gestational age and postnatal age were 39 weeks (range, 27–40) and 43 days (4–203), respectively. Of the 20 infants, 3 were born prematurely at gestational ages of 27, 32, and 32 weeks. The PMA of these 3 infants at time of first PK sampling was 40, 32, and 61 weeks, respectively. From the 20 participants, we collected 92 blood samples. Three samples below lower limit of quantification were excluded from the analysis. The median number of samples per infant was 4 (range, 1–10). Every infant was exposed to at least one other sedating or paralyzing medication within 24 hours of PK sample. The most common concomitant sedating medications were midazolam, methadone, fentanyl, and clonidine (Table 2). The median dexmedetomidine concentration was 0.68 ng/mL (range, 0.07–2.44). All infants received continuous intravenous infusions of dexmedetomidine during the study period, and 19/20 (95%) also received intravenous bolus doses. The median maximum continuous infusion dose of dexmedetomidine during the study period was 1.8 μg/kg/hr (0.5–2.5), not including additional bolus dosing. The majority of infants (16/20; 80%) received a maximum dose of dexmedetomidine >1 μg/kg/hr, and 10/20 (50%) received a maximum dose ≥2 μg/kg/hr.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | Infants exposed (N=20) |

|---|---|

| Postnatal age (days) | 43 (4–203) |

| Postmenstrual age (weeks) | 44 (33–61) |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 39 (27–40) |

| Birth weight (g) | 2900 (640–4054) |

| Body weight (g) | 4020(2000–6000) |

| Females | 11 (55) |

| Albumin (g/dL)a | 2.8 (1.4–3.3) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL)b | 2.0 (0.4–12.1) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.4 (0.1–1.0) |

| Race | |

| White | 8 (40) |

| Black | 10 (50) |

| Multiple races | 2 (10) |

| Cardiac surgery with bypass within 48 hours of PK sample | 4 (20) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 16 (80) |

| Dose | |

| IV bolus (μg/kg) | 0.5 (0.1–3) |

| IV infusion (μg/kg/h) | 1 (0.1–2.5) |

Data are presented as median (range) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data. Where applicable, data was at the time of first pharmacokinetic (PK) sample.

Plasma albumin levels were available in 9 participants.

Plasma total bilirubin levels were available in 10 participants.

Table 2.

Concomitant sedative or paralytic medications within 24 hours of PK sample.

| Infants exposed (N=20) | Samples exposed (N=92) | |

|---|---|---|

| Midazolam | 15 (75) | 50 (54) |

| Methadone | 14 (70) | 53 (58) |

| Fentanyl | 14 (70) | 48 (52) |

| Clonidine | 14 (70) | 34 (37) |

| Lorazepam | 12 (60) | 46 (50) |

| Morphine | 7 (35) | 20 (22) |

| Rocuronium | 6 (30) | 24 (26) |

| Hydromorphone | 6 (30) | 13 (14) |

| Vecuronium | 6 (30) | 13 (14) |

| Phenobarbital | 4 (20) | 7 (8) |

| Diazepam | 1 (5) | 4 (4) |

Data are n (%).

Population PK Model Development and Evaluation

A one-compartment model described the data adequately (Figure 1). Scaling of clearance (CL) and volume of distribution (V) parameters by weight using a fixed exponent allometric relationship (WT0.75 and WT1.0, respectively) resulted in a 40.0-point reduction in the OFV. Additionally, estimation of the exponent of total body weight on CL parameters was attempted but did not result in a significant drop in OFV compared to a fixed exponent allometric relationship. The estimated exponents of total body weight on CL and V were 1.37 and 1.93, respectively. Plots of differences in clearance (etas) versus covariates suggested relationships between clearance and PMA, postnatal age, serum creatinine, and cardiac surgery (Figure 2). Univariable addition of PMA, postnatal age, serum creatinine, or cardiac surgery to the clearance model resulted in a significant decrease in OFV, and the largest drop in OFV (ΔOFV = −10.1) occurred when PMA was added to the model (Table 3). We attempted to use a sigmoidal Emax maturation function to account for change in CL with PMA, but this method did not result in a reasonable estimate of TM50. In the multivariable analysis, only addition of cardiac surgery to the body weight- and maturational (PMA)-adjusted clearance model resulted in a significant drop in OFV (ΔOFV = −5.1) and improved the goodness of fit. However, only the effect of PMA on CL was retained after backward elimination. Covariate effects were not evaluated for V as the majority of the concentration data were from steady-state and did not give enough information about the distribution process to characterize the interindividual variability in volume of distribution.

Figure 1.

Final population pharmacokinetic (PK) model diagnostic plots: observed versus population prediction (A) and individual prediction (B), conditional weighted residuals versus population predictions (C), and time after last dose (D). The solid line in A and B is the line of identity. The solid line in C and D is a reference line at y=0. The dashed lines in A, B, C, and D are smooth lines.

Figure 2.

Eta for clearance (ETA_CL) versus postmenstrual age (PMA) (A), postnatal age (PNA) (B), serum creatinine (SCR) (C), and cardiac surgery within 48 hours of PK sample (D) for the base dexmedetomidine PK model. Each closed circle represents a patient.

Table 3.

Summary of the model building steps.

| Model | OFV | ΔOFVa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable analysis | |||

| Base Model | CL = 51.6*(WT/70)0.75; V = 102*(WT/70) | −161.9 | – |

| PMA on CL using power function | CL = 48.2*(WT/70)0.75*(PMA/43.6)1.94 | −172.0 | −10.1 |

| PMA on CL using maturation function | CL = 3580*(WT/70)0.75*(PMA1.97/(3851.97+PMA1.97) | −172.0 | −10.1 |

| PNA on CL | CL = 52.9*(WT/70)0.75*(PNA/42.5)0.26 | −170.9 | −9.0 |

| SCR on CL | CL = 49.2*(WT/70)0.75*(SCR/0.4)−0.239 | −167.5 | −5.6 |

| CARDSURG on CL | CL = 55.2*(WT/70)0.75*(0.676)CARDSURG | −168.3 | −6.4 |

| SEX on CL | CL = 43.8*(WT/70) 0.75*(1.41)MALE | −165.2 | −3.3 |

| Multivariable analysis | |||

| PMA and Cardiac surgery on CL | CL = 51.4*(WT/70)0.75*(PMA/43.6)1.69*(0.724)CARDSURG | −177.1 | −5.1 |

| PMA and SCR on CL | CL = 47.1*(WT/70)0.75*(PMA/43.6)1.67*(SCR/0.4) −0.173 | −175.0 | −3.0 |

| PMA and PNA on CL | CL = 49.7*(WT/70)0.75*(PMA/43.6)1.33*(PNA/42.5)0.0979 | −172.3 | −0.3 |

| Full model | |||

| PMA and CARDSURG on CL | CL = 51.4*(WT/70)0.75*(PMA/43.6)1.69*(0.724)CARDSURG | −177.1 | – |

| Backward Elimination | |||

| PMA on CL | CL = 48.2*(WT/70)0.75*(PMA/43.6)1.94 | −172.0 | + 5.1 |

| CARDSURG on CL | CL = 55.2*(WT/70)0.75*(0.676)CARDSURG | −168.3 | + 8.8 |

| Final model | |||

| PMA on CL | CL = 48.2*(WT/70)0.75*(PMA/43.6)1.94 | −172.0 | – |

OFV: objective function value; CL: clearance (L/h); V: volume of distribution (L); WT: weight (kg); PMA: postmenstrual age (weeks); PNA: postnatal age (days); SCR: serum creatinine (mg/dL); CARDSURG: cardiac surgery within 48 hours of PK sample.

Change in OFV for the univariable analysis was relative to the base model and for the multivariable analysis was relative to the intermediate PMA on CL model.

Population PK parameters and their precision for the final dexmedetomidine PK model are shown in Table 4. The median individual Bayesian estimate of CL was 1.51 L/h/kg (range, 0.69–2.64). The inter-individual variability estimate of V could not be estimated due to the limited number of subjects and majority of samples representing PK during continuous infusion administration. The body weight normalized population V was 1.5 L/kg. Clearance increased by 4.5% per 1-week increase in PMA at median PMA (44 weeks). Infants with recent cardiac surgery had a lower (~40%) body weight-normalized CL compared to infants without this history (median 1.01 L/h/kg [range, 0.69–1.38] vs. 1.60 L/h/kg [0.90–2.64], respectively; P=0.038). The individual Bayesian estimate of allometrically scaled CL in infants with recent cardiac surgery was 35% lower compared to those without this history (median 34.0 L/h for 70 kg [range, 23.2–46.2] vs. 52.3 [27.8–90.9], respectively; P=0.059).

Table 4.

Population PK parameters.

| Parameter | Estimate | RSE (%) | Shrinkage (%) | Bootstrap CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | Median | 97.5% | ||||

| Structural PK Model | ||||||

| CL (L/h) = θ1*(WT/70)0.75*(PMA/43.6)θ2 | ||||||

| θ1 (L/h) | 48.2 | 9 | – | 41.6 | 47.6 | 56.0 |

| θ2 | 1.94 | 27 | – | 0.82 | 1.93 | 3.27 |

| V (L, 70kg) | 106.0 | 30 | – | 77.1 | 108.0 | 398.9 |

| Inter-individual Variability (%CV) | ||||||

| CL IIV | 35.1 | 32 | 6 | 19.0 | 33.3 | 44.8 |

| Residual Variability | ||||||

| Proportional Error (%) | 19.0 | 20 | 10 | 8.3 | 19.1 | 25.6 |

| Additive Error (ng/ml) | 0.11 | 25 | 10 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.16 |

CL: clearance; V: volume of distribution; WT: body weight; CI: confidence interval; PMA: postmenstrual age; RSE: relative standard error.

The mean value for CL in a typical patient (PMA: 44 weeks; body weight: 4000 g) in this study was 1.43 L/h.

The final model was evaluated using a 1000-set bootstrap analysis; 95% of bootstrap datasets converged to >3 significant digits. The median of bootstrap fixed effects parameter estimates was within 5% of population estimates from the original data set for all parameters. The standardized visual predictive check and traditional visual predictive check revealed a reasonable fit between the observed and predicted dexmedetomidine concentrations. A uniform distribution of calculated observation percentiles was observed at earlier time points where the data points were relatively abundant (Figure 3). There were 20/89 (22.5%) observed concentrations outside of the 80% prediction interval. There were 10/89 (10.1%) observed concentrations outside of the 90% prediction interval.

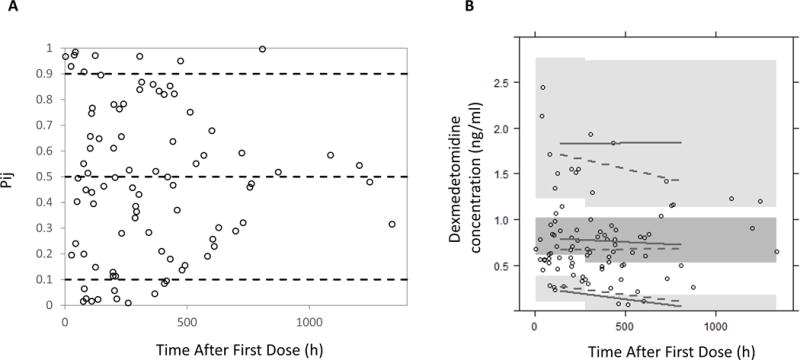

Figure 3.

Standardized visual predictive check of dexmedetomidine observation percentiles versus time after last dose (A). Open circles represent calculated percentiles. Dashed lines represent the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles (bottom, middle, and top, respectively) of model predicted data. Visual predictive check of dexmedetomidine (B). Solid lines represent 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles (bottom, middle, and top, respectively) of model predicted data. Dashed lines represent 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles (bottom, middle, and top, respectively) of observed data. Dark grey area represents 95% confidence interval for the 50th percentile of model predicted data. Light grey areas represent 95% confidence interval for the 5th and 95th percentiles (bottom and top) of model predicted data. Open circles represent observed data.

Safety

Of the 20 infants, 15 (75%) experienced hypotension requiring vasopressors during the study period. Among infants who experienced hypotension, there was no difference between the overall average concentration of dexmedetomidine and the predicted concentration at the time of hypotension (0.42 ng/mL [0.28–0.56] vs. 0.56 [0.25–0.77], respectively; P=0.58). No skin rashes or other adverse events attributed to dexmedetomidine were noted during the study period. Two (10%) infants died during the study period. Both infants who died had severe pulmonary hypertension, and the deaths were deemed unrelated to dexmedetomidine. There was no difference in median maximum levels of dexmedetomidine in infants who died compared to infants who did not die (1.18 ng/mL [0.94–1.42] vs. 0.86 [0.68–1.34], respectively; P=0.38).

Discussion

In this phase I PK study of dexmedetomidine in infants, we used a one-compartment PK model to find that after correcting for body size using weight, PMA and cardiac surgery within 48 hours of PK sample were the most significant covariates. We found that clearance and volume of distribution were 0.87–2.65 L/kg/h and 1.5 L/kg, respectively, for infants with PMA of 33–61 weeks and body weight of 2–6 kg. Our study is the first to report PK of dexmedetomidine in infants at doses >0.2 μg/kg/hr and in any child at doses >0.75 μg/kg/hr. The median maximum dose received by participants in the current study (1.8 μg/kg/hr) was 9 times greater than the maximum dose studied previously for PK in infants and 2.4 times greater than the maximum dose studied previously for PK in older children.17,20,22 At these higher doses, we did not demonstrate an association between dexmedetomidine exposure and adverse events.

When standardized to a 70-kg adult, the plasma clearance of dexmedetomidine (48.2 L/h) reported in this study was lower than typical values reported in adults,7 which is consistent with findings from previous pediatric studies.17–22 Since dexmedetomidine undergoes almost complete hepatic transformation, the relatively lower clearance of dexmedetomidine in infants likely reflects their decreased hepatic enzyme activity compared to adults.16 The estimated plasma clearance of dexmedetomidine for participants in the current study who had cardiac surgery (34.0 L/h for 70 kg) was comparable to the reported value in a study of 45 children after cardiac surgery (39.2 L/h for 70 kg).19 The slightly higher clearance in the previous study may reflect that study’s older population of children (0.01–14.4 years). However, even in older children, clearance can be very variable. In one pooled analysis of 95 children, typical clearance standardized to a 70-kg adult was 42.1 L/h, but there was significant maturation-related variability.26

One other previous study has reported the clearance of dexmedetomidine in infants alone.22 In a phase II/III safety, efficacy, and PK study of dexmedetomidine in 18 mechanically ventilated term neonates (≥36 to ≤44 weeks gestational age) receiving dexmedetomidine 0.05–0.2 μg/kg/h, clearance and steady-state volume of distribution were 0.9 (0.2–1.5) L/h/kg and 3.9 (0.1–10.9) L/kg, respectively.22 The clearance of dexmedetomidine was even lower (0.3 L/kg/h) in 24 preterm neonates. Both of these clearance values are substantially lower than the clearance obtained from our study, which may be a consequence of several factors. First, infants in the previous study were younger (mean postnatal age approximately 2 weeks) than the infants in our study (median postnatal age >6 weeks). In addition, all infants in the previous study were required to be mechanically ventilated, while 4/20 (20%) of infants in our study were not mechanically ventilated. Mechanical ventilation has been reported to decrease clearance of drugs with a high hepatic extraction ratio due to reduced cardiac output and visceral blood flow during mechanical ventilation.27 Dexmedetomidine is a drug with high hepatic extraction, and the presence of mechanical ventilation in all participants in the prior study could partially explain the lower clearance.

In our study, infants with cardiac surgery had lower dexmedetomidine clearance, although the difference was not statistically significant in the population PK model building process. Cardiopulmonary bypass during cardiac surgery has been previously reported to decrease elimination of some drugs due to impairment of renal or hepatic clearance following lowered perfusion and hypothermia.28 Cardiac surgery without cardiopulmonary bypass causes hypoperfusion,29 which could in turn cause a decreased liver clearance of high extraction drugs such as dexmedetomidine. While few data exist in pediatric patients to describe the duration of hepatic impairment, adults can have recovery of laboratory values within several days. We hypothesize therefore that any effect of cardiac surgery on dexmedetomidine clearance would be transient.30 However, given our small sample size, the possible effect of cardiac surgery should be interpreted with caution and needs to be confirmed in a larger study.

Hypotension was common in our infants, with 75% requiring vasopressor treatment during the study period. This finding reflects the severity of illness of the population of infants included in our study; all 4 infants with cardiac surgery experienced hypotension. Episodes of hypotension did not necessarily represent new episodes occurring after the start of dexmedetomidine, and hypotension could have occurred prior to the study period. The prevalence of hypotension is also complicated by the presence of concomitant medications. At Duke University Medical Center, dexmedetomidine is most often used as a second- or third-line sedating agent. Benzodiazepines and opioids were extremely common, and 12 of 20 infants (60%) were exposed to a paralyzing agent during the study period. Clonidine was also a common concomitant medication, reflecting the fact that infants with a long duration of exposure to dexmedetomidine are often transitioned to the oral or transcutaneous clonidine to prevent withdrawal symptoms. These concomitant medications, as well as other clinical comorbidities, likely contributed to the adverse event of hypotension.

The strengths of our study include the opportunistic study design, which offered minimal risk to our participants. By using population PK analysis methods, we were able to obtain important PK information at doses of dexmedetomidine never previously reported. However, our study did have several limitations. Because we did not require additional laboratory testing as part of our study design, we did not have laboratory data from enough infants to include liver dysfunction as a potential covariate in our PK model. While there was a trend toward an effect of cardiac surgery on dexmedetomidine clearance, cardiac surgery could not be established as a significant covariate in our PK model, likely due to the small sample size. In addition, the study design and small sample size limited our ability to make conclusions regarding the exposure-response relationship and safety. Hypotension was common in our population, likely due to high disease severity, and we may have therefore been unable to detect an effect of dexmedetomidine that could be present in infants less critically ill. Because the use of concomitant sedating and paralyzing medications was common and our study was non-blinded and non-randomized, we were also unable to explore efficacy of dexmedetomidine in terms of degree of sedation and analgesia. Without enough data to make strong conclusions on safety and efficacy, we were unable to recommend an “ideal” dosing range for this population. Further prospective studies that prohibit or control for the presence of concomitant sedating or paralyzing agents are needed.

Conclusions

Clearance of dexmedetomidine in our study infants was greater than the previously reported values in neonates but lower than that in adults. Volume of distribution of dexmedetomidine in our study was comparable to that in children and adults. Both PMA and cardiac surgery were important factors affecting dexmedetomidine clearance. Infants with younger PMA and recent cardiac surgery may require relatively lower doses of dexmedetomidine to achieve a level of exposure similar to older patients and those without cardiac surgery. Larger studies are needed to further define these relationships as well as determine the safety and efficacy of higher doses of dexmedetomidine.

Acknowledgments

Funding Information

R.G.G. receives salary support for research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) training grants (5T32HD043029-13), NIH awards (HHSN 275201000003I, HHSN 272201300017I), and from the Food and Drug Administration (HHSF223201610082C). H.W. receives salary support for research from the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award. M.L. receives support from the U.S. government for work in neonatal clinical pharmacology, clinical trials, and cohort studies including FDA R01 FD005101 (PI, Laughon); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute R34 HL124038 (PI, Laughon); the NIH Office of the Director ECHO Coordinating Center U2C OD023375 (PI, Smith, Duke); the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Pediatric Trials Network Government Contract HHSN267200700051C (PI Benjamin, Duke); and as the satellite site PI for the NICHD Neonatal Research Network NICHD U10 HD040492 (PI, Cotten, Duke). E.C. receives research support from the U.S. government (U54 HD090259-01, UM1 AI068632-10, UM1 AI106716-04, HHSN27500034) and consulting fees from Cempra Pharmaceuticals and The Medicines Company. K.Z. is funded by grant KL2TR001115-03 from the Duke Clinical and Translational Science Awards. P.B.S. receives salary support for research from the NIH (NIH-1R21HD080606-01A1) and the NICHD (HHSN275201000003I). M.C.W. receives support for research from the NIH (1R01-HD076676-01A1), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (HHSN272201500006I and HHSN272201300017I), the NICHD (HHSN275201000003I), the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (HHSO100201300009C), and industry for drug development in adults and children (www.dcri.duke.edu/research/coi.jsp).

References

- 1.Barker DP, Rutter N. Exposure to invasive procedures in neonatal intensive care unit admissions. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1995;72(1):F47–F48. doi: 10.1136/fn.72.1.f47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anand KJ, Hickey PR. Pain and its effects in the human neonate and fetus. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(21):1321–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711193172105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsieh EM, Hornik CP, Clark RH, Laughon MM, Benjamin DK, Jr, Smith PB, Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act—Pediatric Trials Network Medication use in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31(9):811–821. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1361933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anand KJ, Barton BA, McIntosh N, et al. Analgesia and sedation in preterm neonates who require ventilatory support: results from the NOPAIN trial. Neonatal Outcome and Prolonged Analgesia in Neonates. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(4):331–338. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anand KJ, Hall RW, Desai N, et al. Effects of morphine analgesia in ventilated preterm neonates: primary outcomes from the NEOPAIN randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9422):1673–1682. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16251-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng E, Taddio A, Ohlsson A. Intravenous midazolam infusion for sedation of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD002052. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002052.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.“PRECEDEX- dexmedetomidine hydrochloride injection, solution” drug label. Revised June 2012, Hospira, Inc. Available from http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/spl/data/76107089-2ec4-4806-ab84-7090a95beab7/76107089-2ec4-4806-ab84-7090a95beab7.xml.

- 8.Berkenbosch JW, Wankum PC, Tobias JD. Prospective evaluation of dexmedetomidine for noninvasive procedural sedation in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(4):435–439. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000163680.50087.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chrysostomou C, Di Filippo S, Manrique AM, et al. Use of dexmedetomidine in children after cardiac and thoracic surgery. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7(2):126–131. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000200967.76996.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burbano NH, Otero AV, Berry DE, Orr RA, Munoz RA. Discontinuation of prolonged infusions of dexmedetomidine in critically ill children with heart disease. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(2):300–307. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2441-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Mara K, Gal P, Wimmer J, et al. Dexmedetomidine versus standard therapy with fentanyl for sedation in mechanically ventilated premature neonates. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2012;17(3):252–262. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-17.3.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barton KP, Munoz R, Morell VO, Chrysostomou C. Dexmedetomidine as the primary sedative during invasive procedures in infants and toddlers with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(6):612–615. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31818d320d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shukry M, Kennedy K. Dexmedetomidine as a total intravenous anesthetic in infants. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007;17(6):581–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.02171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam F, Bhutta AT, Tobias JD, Gossett JM, Morales L, Gupta P. Hemodynamic effects of dexmedetomidine in critically ill neonates and infants with heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33(7):1069–1077. doi: 10.1007/s00246-012-0227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dilek O, Yasemin G, Atci M. Preliminary experience with dexmedetomidine in neonatal anesthesia. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27(1):17–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW, Blowey DL, Leeder JS, Kauffman RE. Developmental pharmacology—drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(12):1157–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su F, Nicolson SC, Gastonguay MR, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine in infants after open heart surgery. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(5):1383–1392. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d783c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vilo S, Rautiainen P, Kaisti K, et al. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous dexmedetomidine in children under 11 yr of age. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100(5):697–700. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potts AL, Warman GR, Anderson BJ. Dexmedetomidine disposition in children: a population analysis. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18(8):722–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diaz SM, Rodarte A, Foley J, Capparelli EV. Pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine in postsurgical pediatric intensive care unit patients: preliminary study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8(5):419–424. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000282046.66773.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petroz GC, Sikich N, James M, et al. A phase I, two-center study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dexmedetomidine in children. Anesthesiology. 2006;105(6):1098–1110. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200612000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chrysostomou C, Schulman SR, Herrera Castellanos M, et al. A phase II/III, multicenter, safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetic study of dexmedetomidine in preterm and term neonates. J Pediatr. 2014;164(2):276–82.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holford N, Heo YA, Anderson B. A pharmacokinetic standard for babies and adults. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102(9):2941–2952. doi: 10.1002/jps.23574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang DD, Zhang S. Standardized visual predictive check versus visual predictive check for model evaluation. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(1):39–54. doi: 10.1177/0091270010390040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potts AL, Anderson BJ, Warman GR, et al. Dexmedetomidine pharmacokinetics in pediatric intensive care–a pooled analysis. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19(11):1119–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richard C, Berdeaux A, Delion F, et al. Effect of mechanical ventilation on hepatic drug pharmacokinetics. Chest. 1986;90(6):837–841. doi: 10.1378/chest.90.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buylaert WA, Herregods LL, Mortier EP, Bogaert MG. Cardiopulmonary bypass and the pharmacokinetics of drugs. An update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1989;17(1):10–26. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198917010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohri SK, Velissaris T. Gastrointestinal dysfunction following cardiac surgery. Perfusion. 2006;21(4):215–223. doi: 10.1191/0267659106pf871oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabzi F, Faraji R. Liver function tests following open cardiac surgery. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2015;7(2):49–54. doi: 10.15171/jcvtr.2015.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]