Abstract

In this paper a new approach which is based on a collaborative system of MicroGrids (MG’s), is proposed to enable household appliance scheduling. To achieve this, appliances are categorized into flexible and non-flexible Deferrable Loads (DL’s), according to their electrical components. We propose a dynamic scheduling algorithm where users can systematically manage the operation of their electric appliances. The main challenge is to develop a flattening function calculus (reshaping) for both flexible and non-flexible DL’s. In addition, implementation of the proposed algorithm would require dynamically analyzing two successive multi-objective optimization (MOO) problems. The first targets the activation schedule of non-flexible DL’s and the second deals with the power profiles of flexible DL’s. The MOO problems are resolved by using a fast and elitist multi-objective genetic algorithm (NSGA-II). Finally, in order to show the efficiency of the proposed approach, a case study of a collaborative system that consists of 40 MG’s registered in the load curve for the flattening program has been developed. The results verify that the load curve can indeed become very flat by applying the proposed scheduling approach.

Index Terms: Demand side management, demand flattening function, Fourier transform, multiobjective optimization, smart grid, dynamic scheduling, NSGA-II

Introduction

Achieving energy conservation would require developing an efficient control strategy of in-home appliances, especially in the presence of increasing ownership of distributed generation, such as renewable energy sources. The recent availability of smart home appliances supported by communicant networking was the main force behind the growing interest in developing advanced DSM [1]–[3]. While there has been a great deal of work done, particularly on wireless communication technologies for smart grid [4]–[11], the main challenge is the use of DSM as an efficient tool for load shaping in order to allow electrical appliances to operate during certain time frames (e.g. a day or a part of day) [12], [13]. Bear in mind that a DSM design strategy has to rely on the optimization of different objective functions, which also depend on the involvement of an operator. In fact, the main reason behind such an optimization is to reduce the gap between the valley and the peak of the demand curve [14]. In the case of renewable generations, this can be based on tracking the power generation curve [15], [16]. From the point of view of the system operator, for instance, [15] presents an analytic study of centralized load dispatch, which is based on unit commitment and power reserve requirements of the power system. Further studies have been conducted for handling DSM strategies that use residential appliances currently available on the market [17]–[19]. With respect to the home energy management system, [20] discusses a tradeoff between expected costs and the risk of electricity price uncertainties. The authors in [21], propose a home appliance scheduling approach which uses a stochastic formulation of the consumed power cost. Other studies consider a tertiary operation between the electricity provider and the consumer as an aggregation operator. One example is the study presented in [22] for a large number of residential users and several aggregation operators. It is based on a pricing structure that allows the customer the choice of electricity supplier in a fully deregulated market scenario. In addition, the study in [23] aims at reaching an adequate number of small energy consumers in order to quantify the trade-off between load control and tolerable service delays.

Since the main purpose behind DSM is to control power consumption by minimizing power peaks [7], [17], [22], several household appliance manufacturers have already introduced smart equipment, such as smart washing machine, dryer, heat water, dishwasher, electric vehicle battery, etc. Taking advantage of these functionalities, residential DSM could efficiently contribute to reshaping the electric demand curve. Most strategies developed so far have primarily concentrated on using DSM for tracking of a specific generation curve, especially in the case of large renewable sources which are mostly based on pricing [13]. In addition, there are some studies that focus mainly on the use of electrical vehicle charging strategies to fill the valley of total load curve [24]–[26]. In fact, these programs can indeed provide a reciprocal benefit to both the grid operator and program participants. For example, incentives such as bill reduction can be offered to program participants. Also, they can further benefit by sharing renewable sources in the form of collaborative microgrids, such as balancing renewable source generation.

The study presented in this paper proposes a novel scheduling approach that is aimed at minimizing the typical deviation of consumed power over a period T, as the optimization objective. The main purpose behind the optimization problem is to calculate the delay of each deferrable load. Therefore, the first contribution of this work is the categorization of household appliances into flexible and non-flexible deferrable loads (DL’s) depending on their electrical components. The power profile of these appliances is then presented as a sum of several rectangular pulse functions. The second contribution is developing an analysis of the flattening function of the standard deviation of consumed power over a certain period of time using Fourier Transform for the power profile of each appliance. Then, by using the Parseval theorem”, the flattening function has been simplified to form a summation of simple functions. In addition, non-deferrable loads, such as unscheduled loads and renewable source generation have been presented as a predicted curve. The final contribution is developing a dynamic scheduling algorithm based on the resolution of two successive multiobjective optimization problems. The first optimization aims at simultaneously minimizing the flattening function and typical deviation of non-flexible DL’s delays. The second deals with the simultaneous optimization of flexible DL’s power standard deviation and a satisfactory error rate. NSGA-II [27] has been used to solve both aforementioned problems. It should be noted that the proposed scheduling approach can be applied to both centralized and distributed control systems. Finally, the proposed approach has been deployed in order to schedule dishwashers as non-flexible DL’s and water heaters as flexible DL’s of a community of 40 users. An example of non-deferrable loads with PV generation has been simulated showing the validity of the proposed approach for tracking a curve generation. To the best of our knowledge, the proposed appliance scheduling approach is the first work aiming to smooth the total load curve using household appliance. Therefore, the results discussion is based only on comparing the proposed approach results to the original data in the absence of DSM.

The paper is structured as follows: Section II presents the context of the proposed scenario and the modeling of household appliances. Section III develops the formulation of dynamic flattening function optimization followed by experimentation set up and results in Section IV. Finally, Section V provides the conclusion and some perspectives.

II. DSM-Based Collaborative Smart Building

Currently, the idea of designing collaborative smart buildings is becoming a real challenge. Indeed, the emergence of power systems toward smart grids and the growing use of smart household appliances are the main driving forces towards the use of demand side management. This can have a major impact on the way in which future buildings will operate. The proposed DSM-Based collaborative smart building is assumed to be composed of several collaborative microgrids that are capable of controlling their own electrical appliances in the framework of demand side management. This would permit the system manager to decide on the activation and operation of their deferrable loads.

A. Description of collaborative smart building

Let us consider a scenario of a set 𝒩 microgrids operating in a collaborative framework conducted by an electricity provider as shown in Fig. 1. Each microgrid has a set of schedulable loads which can be activated over a given period. Consider that each MG is equipped by a Smart Control Panel (SCP) and Load Control (LC) for each schedulable appliance. LC’s are controlled by SCP in order to execute decisions about the scheduled activation time of loads in set ℐ and the the scheduled power profile of loads in set 𝒥. The SCP is the general controller in each MG. It is designed to collect all the power consumption information sent from LC’s of the same MG and will then communicate the shared information to the operating center.

Fig. 1.

Collaborative Smart building

B. Deferrable loads modeling

A deferrable load is a load that needs to be supplied for part of the day and can be deferred in time. This type of load can be used by residential, commercial or industrial consumers. Currently, with the increased awareness of energy efficiency, most electrical equipment are designed with different power levels. Mainly, household appliances are equipped with different sensors providing information about the required energy to achieve a certain task for a given duration. For example, electrical vehicle batteries, air-conditioners, tumble dryers, electric water heaters, fridges, and freezers that are currently available in the market, have several levels of power consumption (e.g., 9-level for fridges and freezers). Therefore, it can be considered that the supply of a smart appliance as a combination of several loads supplied for a defined duration beginning at the time of the first power segment activation. Now, let’s consider the operation of two types of household machines where the first uses an ordered multi power level (such as a dishwasher) and the other needing only to achieve a necessary energy level during a given period of time (such as a heat water).

1) Smart Dishwasher

Currently most machines have four operational power levels, depending on the stage in which they operate. In the Pre-Wash stage, the machine sprays water onto the dishes to loosen soil particles. At this stage it operates at medium power (level 2). For the Main Wash, once the water reaches the desired temperature followed by mixing detergent to form a solution, the machine then operates at the higher level (level 3). The lowest power level (level 1) is triggered during the Intermediate Rinsing Cycles, removal of residues remaining on the surface of the machine, and/or when the loads are rinsed with fresh water. Finally, at the Final Rinse/Drying Cycle stage, rinse aid is added and the water is heated up. Then, the water is removed and the load dried by the remaining heat. At this stage the machine operates at level 4. This category of appliances is defined as Non-flexible Deferrable Loads (NDL). Other appliances operating as NDL include washing machines and dryers, which use electrical motors for their operations.

2) Smart Heat Water

The manufacture of this type of appliance is based on heat production using resistive components. Therefore, they can easily operate at any desired power by simply changing the resistance value with a controllable rheostat. Currently, several water heater products are equipped with smart grid adaptive positioning that can be used for future utility management. This category is defined as Flexible Deferrable Loads (FDL), which includes mainly appliances whose functioning is based on resistive components.

C. Non-deferrable loads modeling

It should be noted that there are always some non-programmable class of loads, such as lighting, television, computer, etc., where their usage is randomly activated and therefore cannot be scheduled over a specific period of time.

However, in most cases their operation can be forecast at several increments (a day-ahead, an hour-ahead, or even minutes ahead). Furthermore, in the case of renewable sources that normally produce variable and non-controllable energy, the generated power is considered as a negative load. Therefore, in our model the total non-deferrable load is defined as the summation of two types of loads: non-programmable and renewable.

D. Load curve flattening

Non-flexible DL’s are deferrable over time with unchangeable power shape, while flexible DL’s are only constrained by the supply of required energy over a specific duration, regardless of the power shape. Therefore, non-flexible DL’s are less manageable than flexible DL’s. Here an analysis of the load flattening function in the case of a Non-flexible DL is introduced for 1-level and N-level appliances. This is then followed by the formulation of the flattening function of a flexible DL.

1) flattening function of 1-level appliances

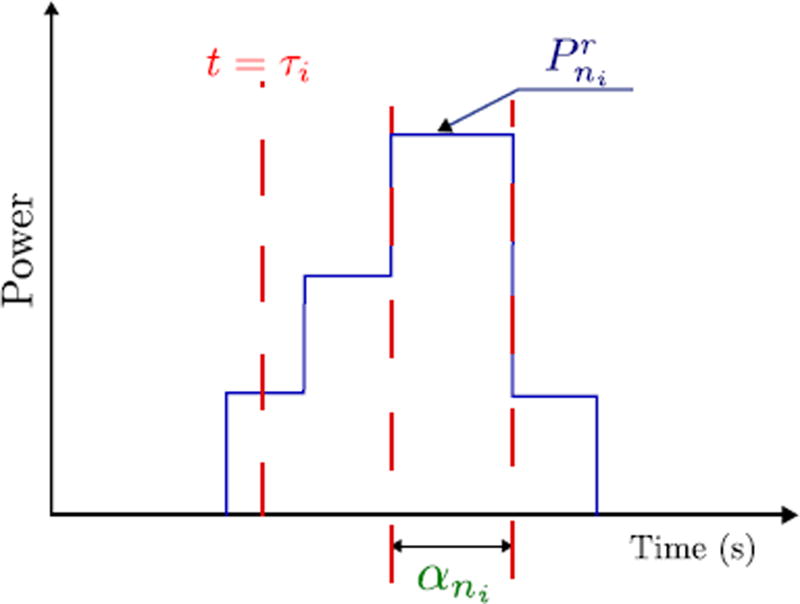

Consider the case of a set ℐ of 1-level appliances. The power profile of a load i in ℐ can be modeled as a unified square function multiplied by the rated power of load i for a time interval αi (Fig. 2).

| (1) |

where τ = {τi}i∈ℐ is the vector of activation schedule of the plugged appliances. By using the transform of Fourier of a pulse pi(t − τi),

| (2) |

with

and

Fig. 2.

1-level load operating cycle

Then, according to Parseval theorem,

| (3) |

The equations (18), (19), (20) and (21), in the Appendix, develop the calculus detail of the integral which reaches the following formulation of flattening function,

| (4) |

with,

| (5) |

2) flattening function of N-level appliances

Let’s consider a set ℐ of N-level appliances that operates according to a specified duty cycle with N levels of power consumption (Fig. 3). The power consumption of an N-level appliance can be expressed as follows,

| (6) |

where

| (7) |

Fig. 3.

N-level load operating cycle

This form allows to consider each level of a N-level load as a set of N 1-level loads. Then, the flattening function of a set ℐ of N-level appliances is given in (8),

| (8) |

By analogy with the function in (1), (8) can be expressed as,

| (9) |

with,

3) flattening function of flexible appliances

In this case, consider a set 𝒥 = {1, …, J} of flexible loads and T′ the operating period of these loads. The power profile of this kind of load can change over time according to the specific scheduling strategy and is constrained only by achieving the required energy Ej over the period T′. Fig. 4 shows two possible power profiles (Figs. 4a and 4b) of the same required energy to supply a given appliance. It is assumed that a base load power P(t′) has already been scheduled. Later, P(t′) notices the required power for supplying the non-flexible DL. Under these conditions, the flattening function can be expressed as follows,

where R = {Rj}{j∈𝒥} is the power profiles of the set 𝒥 of flexible DLs with Rj = {Rj(t), …, Rj(t+T′)} representing the power values of the appliances j ∈ 𝒥 = {1, …, J}. Note that the power profile of each appliance has to achieve the requested energy Ej over the period T′.

Fig. 4.

Two power shapes (a) and (b) of a Flexible DL operating

4) flattening function of non-deferrable loads

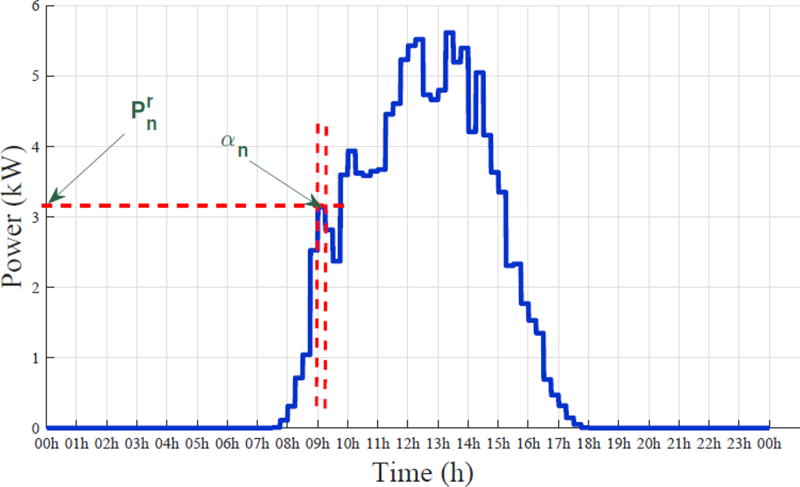

The power profile of this type of loads cannot be reshaped either for unscheduled loads or renewable sources generation, but can be only treated as a predicted load. Moreover, the forecasts of these loads are calculated periodically, for instance, each 15 minutes. Thus, the power curve of residual load can be approximated by its predicted value over N = 96 time intervals. Consequently, this type of loads can be approximated by an N-level appliance with a delay activation time equals to null value (τ = α/2). Fig.5 illustrates an example of a photovoltaic power generation curve with power capacity of 6kW. In this paper, only the case of photovoltaic plant as example of non-deferrable loads is considered by lack of forecasts data of other loads in this class. However, there is no restriction and any forecasts of a power profile can be studied in the same way as the photovoltaic power profile.

Fig. 5.

Power generation of EMI’s Photovoltaic plant during the day of January 29th, 2016 [28].

III. Dynamic flattening function optimization

The dynamic aspect of load flattening is mainly concerned with verifying the readiness of household equipment to be supplied in the next period. This dynamic occurs at each iteration t and after each time step Δt = T′ where T′ < T is the period of flexible DL’s. The algorithm assigns an activation moment to the set of appliances involved in optimization of the flattening function. Therefore, the dynamic flattening function is based on the adaptation of the previous defined function with a variable integration interval, from [0; T] to [t; t + T]. Therefore, the dynamic flattening function would be the same as (9), except in this case τni where it is substituted by as defined in (12).

| (10) |

By using this variable change u ← u − t, the function in (10) can be given as,

| (11) |

where

| (12) |

A. Dynamic flattening function optimization

Since the proposed approach deals with two different load categories (flexible and non-flexible DL), the optimization problem is defined at two stages to resolve two successive optimization problems as described in the proposed appliances scheduling algorithm. The first optimization problem (sub-problem 1) reaches optimal activation time of the first loads category (Non-flexible DL’s). This optimization aims at achieving simultaneous minimization of both the flattening function f (t, τ) (10) and the standard deviation of the loads activation delay l(τ) (14). While the second optimization problem (sub-problem 2) deals with flexible DL’s by searching for that minimizes the standard deviation of both the peak power g(R) (16) and the satisfaction error of the needed supplied energy s(R) (17). The algorithm is running dynamically in order to take in account the dynamic aspect of the appliances plug-in.

B. Optimization method

Solving both optimization problems defined in the proposed algorithm would require deploying a suitable multiobjective optimization method. In this approach fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm; NSGA-II [27] is used. This algorithm is known for its efficiency in solving multiobjective problems [29]–[31]. It should be noted that NSGA-II is the second version of NSGA that overcomes the computation complexity, as well as the non-elitist characteristic of its solutions [26]. Based on features of this optimization method, it is first defined the parameters of the deployed method, mainly the number of generations and the size of the population which corresponds to the size of solution set, called also Pareto set. Then, the range of variation of the decision vector (DV), as well as the initial values are determined. For the sub-prob 1, the DV corresponds to the activation moment of NDLs τ = {τi}{i∈ℐ} while, for sub-prob 2, it corresponds to the power profile of FDLs R = {Rj}{j∈𝒥}. After that, the optimization objectives of each sub-prob are defined in order to be evaluated during the process of NSGA-II, according

Algorithm.

Dynamic Appliances Scheduling

| 1: | INPUT: Period of NDL T, Period of FDL T′, Rated power and Operating duration αi for all NDLs, Lower and uper bounbs and for all FDLs | ||||||

| 2: | OUTPUT: Scheduled activation of NDL , Power profile of FDL . | ||||||

| 3: | PROCEDURE: | ||||||

| 4: | for t = t0 to T do | ||||||

| 5: | Check plugged NDL appliances ℐ′(t) | ||||||

| 6: | ℐ ← ℐ ∪ ℐ′(t) | ||||||

| 7: | Calculate f(t, τ) for all i ∈ ℐ as defined in (10) | ||||||

| 8: | Optimize Sub-Problem 1:

|

||||||

| 9: | for i = 1 to I do | ||||||

| 10: | if then | ||||||

| 11: | ℐ ← ℐ \ {i} | ||||||

| 12: | end if | ||||||

| 13: | end for | ||||||

| 14: | Check plugged FDL appliances 𝒥 (t) | ||||||

| 15: | Read current needed energy Ej(t) for all j ∈ 𝒥(t) | ||||||

| 16: | Calculate | ||||||

| 17: | Check plugged appliances in J | ||||||

| 18: | Optimize Sub-Problem 2

|

||||||

| 19: | t ← t + T′ | ||||||

| 20: | end for |

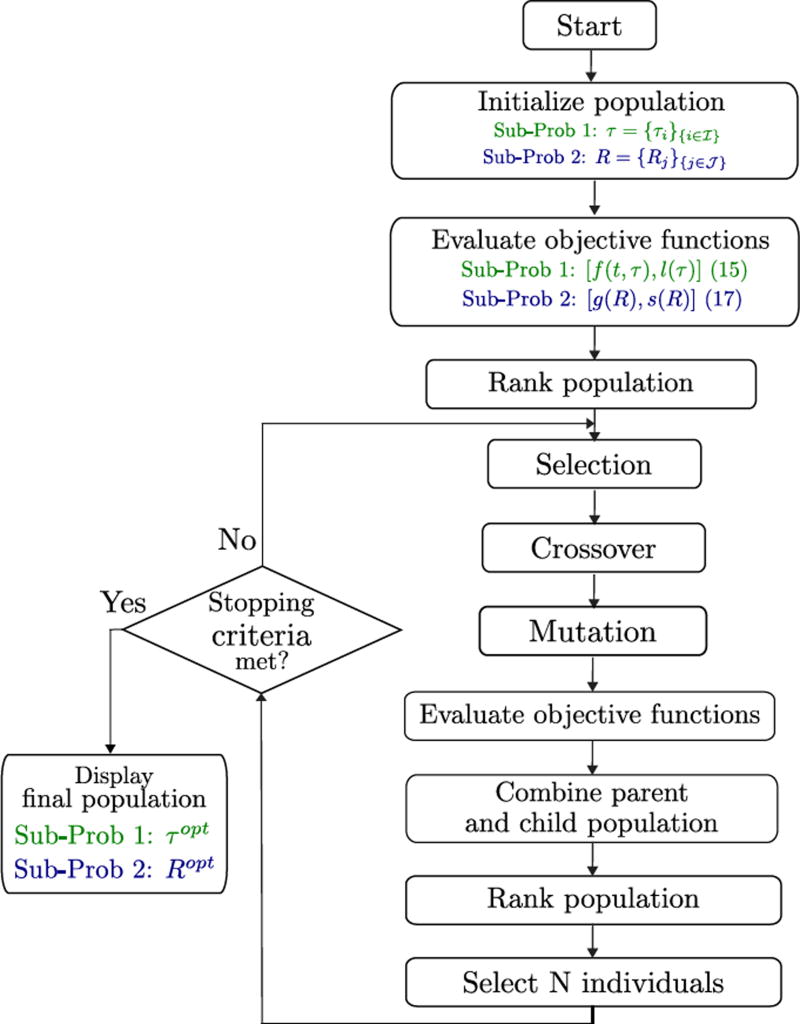

to the flow chart of the proposed method shown in Fig. 6. The final goal of the method is to present the optimal solutions corresponding to the objectives of each sub-problem: for sub-prob 1 and for sub-prob 2. Since these are multiobjective problems, the solution for each is a set of non-dominated solutions called “Pareto solutions”. The basic operations of NSGA-II are as follows:

Fast Non-dominated Sorting: This is based on two entities: the number of solutions dominating each solution in the current population (i.e., rank) and the set of dominated solutions associated with each solution.

Density estimation (crowding distance): presents the density of solutions surrounding a particular point in Pareto front. It is the average distance of two points on either side along each of the objectives.

Crowded-Comparison Operator: which compares two solutions on the basis of the rank and crowded distance. The best solution is the one with smaller rank. In the case of rank equality, the solution with smaller crowded distance would then be selected.

Fig. 6.

Flow chart of NSGA-II

Fig. 6 presents the main loop of NSGA-II which starts by initializing the population and assigning to each point the appropriate rank. Then, reproduction operators such as tournament selection, recombination and mutation are used to create the offspring population. After that, the two populations parent and offspring are combined and sorted following the crowded-comparison operators mentioned above. More details and complexity evaluation of NSGA-II can be found in [27].

IV. Simulation and results

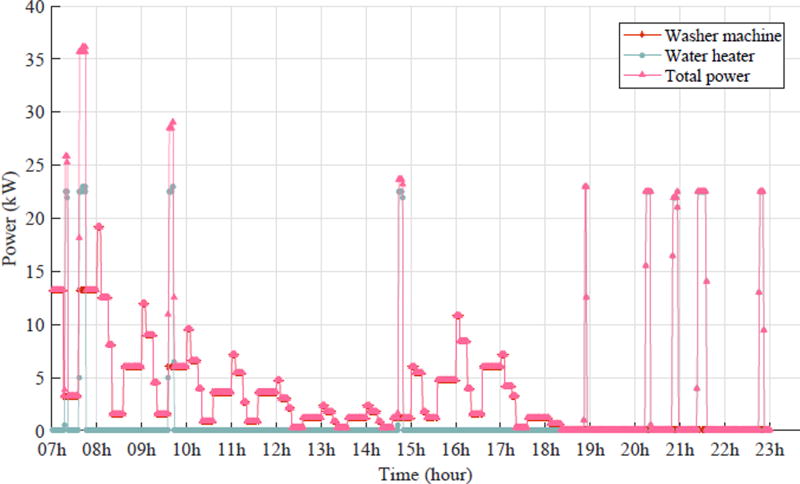

The proposed approach has been applied in order to schedule household appliances for 40 collaborative MG’s that are registered in the program of the load curve flattening. In our first case study, every registered MG includes one flexible DL (e.g., water heater) and a non-flexible DL (i.e., dishwasher). All 40 dishwashers are restricted to operate within a delay period of T = 6h. For these experiments, the residential load curve taken from [32] has been used, which corresponds to the real time single household appliances power profile. For 40 users, the instantaneous power of dishwasher machine characteristics are shown in Table I. The instantaneous power of each machine is based on the following equation.

TABLE I.

Dishwasher characteristics

|

|

|

|

|

α1 (min) | α2 | α3 | α4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 15 | 20 | 30 | 15 |

As suggested, the scheduling algorithm runs dynamically at each time slot t − δt, where δt = δt1 + δt2 is the algorithm execution time, and δt1 and δt2 are the computational times required to solve sub-problems 1 and 2 successively. At each time slot, it takes into account the new appliances requesting to be supplied during the next period ([t; t + T]). The proposed approach deals with two appliance categories, flexible and non-flexible DL, depending on the supplying flexibility as well as the electrical components of the equipment (motor or resistive component).

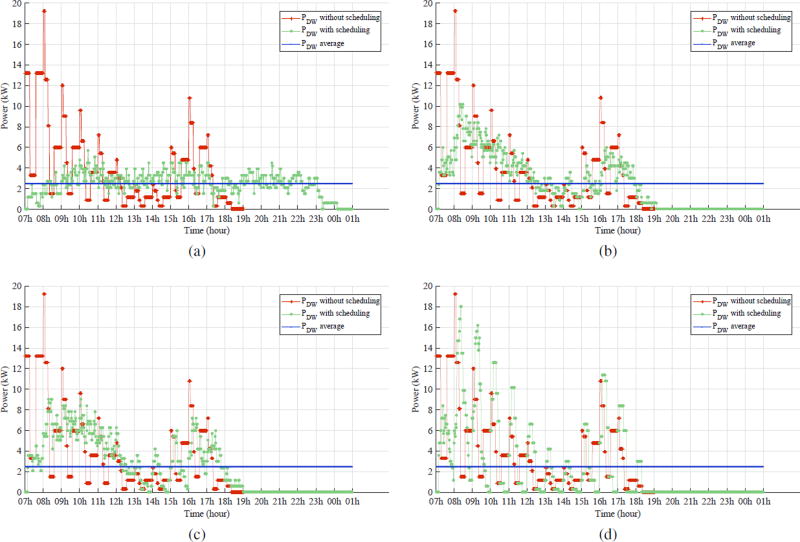

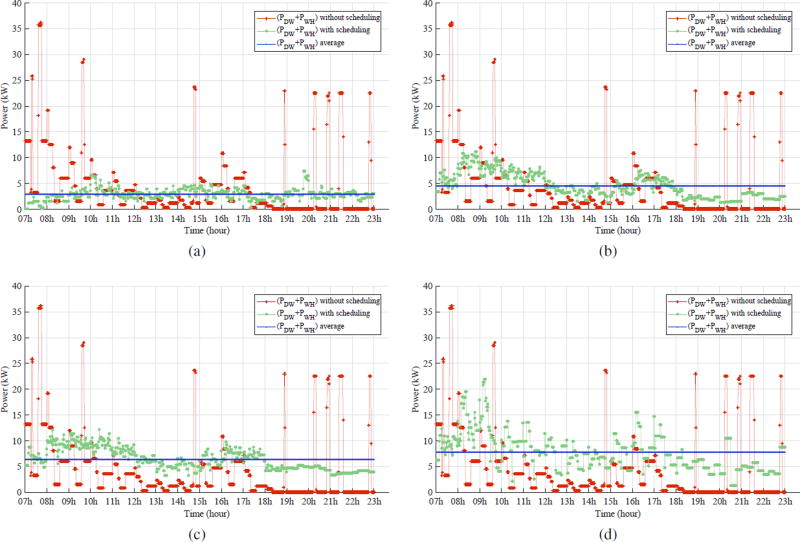

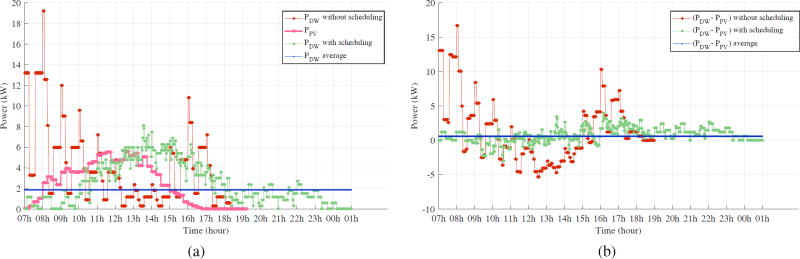

Therefore, the algorithm reaches the resolution of two multiobjective sub-problems at each slot time. The first calculates the optimal activation time of NDL, whereas the other presents the optimal power profiles of FDL. Moreover, each sub-problem deals with two objectives and then develops a set of compromise solutions. NSGA-II has been deployed to resolve these problems with a number of generation of 200 and a population size of 200. The simulations have been run on an Intel i7-4600U processor at 2.7 GHz using a Matlab code. The execution time of these problems depends on the number of variables corresponding to the appliances number. In this section, the power profile of dishwashers, water heaters and PV generation are signified by PDW, PWH and PPV, respectively. In addition, the obtained load curve using the proposed Algorithm (red curve with red dots in Figs. 9, 10 and 11) is compared to the load profile of the actual power profile without scheduling (red curve with red stars in Figs. 9, 10 and 11) and to the average load power (blue curve in Figs. 9, 10 and 11).

Fig. 9.

Power consumption before and after scheduling dishwashers considering Pareto solution corresponding to (a) minimum NDL flattening S11, (b) average NDL delay S12, (c) average NDL flattening S13 and (d) minimum NDL delay S14.

Fig. 10.

Power consumption before and after both scheduling dishwashers and shaping required energy by water heater considering Pareto solutions corresponding to the couple of solutions (e) (S11, S21), (f) (S12, S22), (g) (S13, S23) and (h) (S14, S24).

Fig. 11.

Power profile of (a) dishwashers and (b) considering PV power as negative load in the case of tracking a PV generation

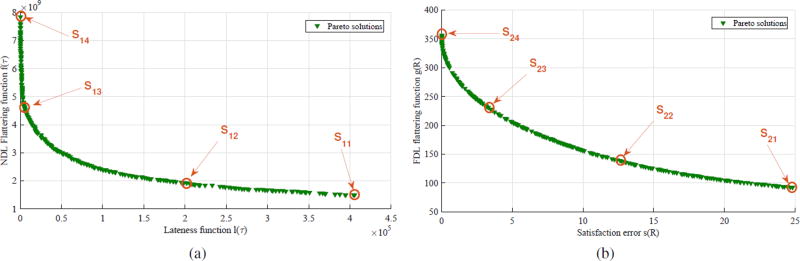

The solution of sub-problem 1 presents the Pareto front consisting of compromised solutions of the flattening function and the standard deviation of all resulting delays caused by the scheduling of the current plugged appliances. Fig. 8a illustrates an example of obtained curve at a given slot time t (for instance at t = t0). The choice of a solution from a Pareto curve depends on the decision makers strategy; whether minimizing the flattening function or the delay to supply current appliances. In this case study, four solutions have been selected to achieve different preferences, such as the minimum and median values of NDL flattening function (S11 and S13 respectively), and the minimum and median values of NDL delay (S12 and S14 respectively). These solutions correspond to an arrival rate of 11 appliances at time slot t = t0 (t0 = 7h). Performances such as standard deviation of power profile σ (PDW) and the standard deviation of the lateness resulting from scheduling σl of the four selected solutions besides the case of the same appliances turned on all at t = t0 are illustrated in Table IV. Then, the solution S11 corresponds to the minimum of NDL flattening function f (τ) which presents the minimum standard deviation of the total power profile. The corresponding power profile to this solution is illustrated in Fig. 9a. The activation time is spread and the instantaneous power stays very close to the mean value. While the solutions S12 and S13 present a compromise solutions of power deviation and activation delay. Therefore, Figs. 9b and 9c show a power profile smoother than the original profile, but not as smooth as the result of S11. Finally, S14 corresponds to the minimum standard deviation of all activation delays and Fig. 9d illustrates the power profile corresponding to this solution which shows the maximum variability of the power.

Fig. 8.

Pareto solutions, at t = t0, of (a) Sub-problem 1 and (b) sub-problem 2 using NSGA-II

TABLE IV.

Selected solutions from Pareto set of sub-problem 1

| Solution | τ1(min) | τ2 | τ3 | τ4 | τ5 | τ6 | τ7 | τ8 | τ9 | τ10 | τ11 | μ(PDW) (kW) | σ(PDW) (kW) | μl (min) | σl (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before scheduling | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.65 | 4.15 | 0 | 0 |

| S11 | 0.10 | 14.77 | 42.38 | 81.97 | 111.12 | 143.54 | 171.68 | 219.48 | 247.82 | 320.45 | 349.43 | 1.65 | 1.01 | 170.26 | 107.53 |

| S12 | 0.20 | 9.04 | 24.06 | 32.20 | 53.20 | 90.22 | 119.46 | 156.44 | 184.09 | 220.54 | 248.64 | 1.65 | 1.50 | 113.78 | 81.41 |

| S13 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 1.60 | 3.51 | 8.77 | 15.37 | 20.27 | 20.99 | 27.67 | 29.93 | 45.04 | 1.65 | 3.16 | 17.37 | 13.60 |

| S14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.94 | 2.21 | 3.96 | 4.30 | 10.57 | 1.65 | 4.01 | 2.22 | 3.20 |

| Execution time δt1 = 40.67s | Scheduling period of NDL T = 6h | At time slot t = t0 | |||||||||||||

Once the solution of sub-problem 1 is chosen, this solution is taken into account by the second optimization problem. The resolution of sub-problem 2 aims at minimizing the total deviation between the whole consumed power, together with minimizing the satisfaction error of the required energy. This problem also presents a set of compromise solutions as illustrated in 8b. Four solutions from Pareto front are selected reflecting different preferences of the decision maker, the minimum and median values of FDL flattening function (S21 and S23 respectively), and the minimum and median values of the satisfaction error (S22 and S24 respectively). More details about these solutions are presented in Table V. Comparing the optimal solutions to the case of appliances supply before scheduling both NDLs and FDLs, by smoothing the power curve, the standard deviation of the power can pass from 10.54kW to 1.09kW which is very close to the result of S11 of sub-problem 1. However, in this case the satisfaction error is very large. Fortunately, the Pareto front present a multitude of solutions and this is only one extreme solution. Therefore, depending on the required satisfaction, the algorithm user can chose the appropriate solution. Fig. 10 illustrates the power profile resulting from the four selected solutions. In the four cases, the instantaneous power is smoother than the original curve, but the degree of deviation from the average value is different depending on the location of each solution on Pareto curve whether it prioritizes the minimization of the FDL flattening function or the satisfaction error.

TABLE V.

Selected solutions from Pareto set of sub-problem 2

| Solution | R1(kW) | R2 | R3 | R4 | μ(PDW + PWH)(kW) | σ(PDW + PWH)(kW) | Ereq (kWh) | (E(R) − Ereq) (kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before scheduling | 0 | 6 | 0 | 13.93 | 14.88 | 10.54 | 299 | 0 |

| (S11, S21) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.04 | 1.09 | 299 | 298.95 |

| (S12, S22) | 3.20 | 1.83 | 0.84 | 0.31 | 5.37 | 5.27 | 299 | 206.21 |

| (S13, S23) | 3.94 | 3.35 | 3.55 | 3.46 | 6.50 | 4.62 | 299 | 84.43 |

| (S14, S24) | 6.29 | 2.50 | 3.31 | 7.83 | 9.40 | 9.43 | 299 | 7.2892e − 04 |

| Execution time δt2 = 5.12s | Scheduling period of FDL T′ = 1h | At time slot t = t0 | ||||||

Finally, to show the performance of the proposed algorithm even in the presence of non-deferrable loads, a simulation using PV generation has been developed. Herein, any curve of forecasts (e.g., a day-ahead) can be used as a known parameter to the first optimization problem (sub-problem 1). Indeed, the data illustrated in Fig. 5 has been used in this simulation. Therefore, Fig. 11a illustrates the resulting power profile from sub-problem 1 considering the PV generation. It is notable that the consumed power by the scheduled dishwashers, during the time range 7h–12h, is less than the PV production but still having the shape tracking the PV generation. After this range, with the arriving of other requests to supply, the consumption has grown and then exceeded the PV production. To verify that the total load (dishwashers and PV generation) is effectively realizing the flattening of the total load curve, Fig. 11b illustrates the power profile of the total load which is seen by the side of the main grid. Tracking the PV generation is an example of tracking a known curve of generation (PV, wind power, concentrated solar power, etc). In general, it can be any curve representing the loads called previously non-deferrable loads including also the unscheduled loads.

V. Conclusion

This paper presents a new approach for scheduling household appliances in order to realize the load curve flattening by smoothing the total load curve. The proposed approach deals with two types of loads, which allow it to take into account almost the entire spectrum of used household appliances. Moreover, the plug-in decisions to use household equipment generally vary dynamically. Therefore, this approach is based on a dynamic algorithm which strives to resolve two successive multiobjective optimization problems. The first gives the activation scheduling towards flattening the power consumption of non-flexible DL’s and the second presents the power profiles of flexible DL’s. The results verify the efficiency of the proposed scheduling approach and allow a great reduction of the standard deviation of power profile while considering other objectives. Moreover, the approach has been deployed in the case of using renewable generation and the results show the validity of this approach to deal with tracking renewable generation, or generally with any required shaping of the demand curve.

Fig. 7.

Power consumption by dishwashers and water heater of a community of 40 users

TABLE II.

Hourly arrival rate of dishwasher

| Time (h) | 7h | 8 – 9h | 10 – 11h | 12 – 14h |

| Arrival rate | 11 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| Time (h) | 15h | 16h | 17h | 18 – 23h |

| Arrival rate | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

TABLE III.

Average required energy of water heater

| Time (h) | 6h | 7h | 8h | 9 – 12h | 13h | 14 – 16h | 17h | 18h | 19h | 20h | 21 – 23h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E (kWh) | 299 | 0 | 147 | 0 | 135 | 0 | 59 | 0 | 321 | 265 | 135 |

Acknowledgments

Prof. ANIBA would like to thank the Institute of Research in Solar Energy and New Energies (IRESEN), Morocco, for their support within the InnoTherm-13-MicroCSP project.

Nomenclature

Major Abbreviations

- MG

MicroGrid

- RES

Renewable Energy Source

- DSM

Demand side management

- SCP

Smart Control Panel

- LC

Load Controller

- FDL

Flexible Deferrable Load

- NDL

Non-flexible Deferrable Load

- NSGA-II

Fast and Elitist Multiobjective Genetic Algorithm

Major Symbols

- i

Non-flexible Deferrable Load (NDL), i ∈ ℐ = {1, …, I}

- j

Flexible Deferrable Load (FDL), j ∈ 𝒥 = {1, …, J}

- T

Period of NDLs scheduling

- T′

Period of FDLs scheduling

- τi

Scheduled activation of the NDL i

Plug-in time of the NDL i

Rated power of load i ∈ ℐ

- αi

Operating duration of load i ∈ ℐ

- Rj

Scheduled profile of the FDL j, Rj = {Rj (1), …, Rj (T′)}

Upper bound on Rj

Lower bound on Rj

- Ej

Needed energy to be supplied on period T′

Biographies

Hasnae Bilil (S’11-M’15) received the Dipl.-Ing in 2010 and the Ph.D. degree in 2014 in electrical engineering from Mohammadia School of Engineers, Rabat, Morocco. She is now a teaching assistant at Mohammadia School of Engineers, University Mohammed V in Rabat, Morocco. Since August 2015, she is conducting research on Smart grid as Post-Doc at National Institute of Standards and Technology. Her current research interests include renewable energy sources, power system state estimation, smart grid and demand side management.

Ghassane Aniba Ghassane Aniba (IEEE S03IEEE M10) received the Ph.D degree in telecommunications from Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique, Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique - Energy, Materials and Telecommunications (INRS-EMT), Montreal, Canada, in 2010, and the Dipl.-Ing. degree in telecommunication engineering from the Institut National des Postes et Tlcommunications (INPT), Rabat, Morocco, in 2002. In 2010, after a postdoctoral position at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), KSA, he joined Ecole Mohammadia dingnieurs (EMI), Rabat, Morocco, where he is currently an Associate Professor in Electrical and Telecommunication Engineering. He was the chair of the cooperative techniques and relays session at the 20th International Conference on Telecommunications 2013. He is the principal coordinator of the two IRESEN Projects: MicroCSP project (2014–2017) within the InnoTherm III call for projects. His current research interests include Smart Grids, traffic modeling in green cognitive networks, cooperative wireless networks and wireless sensor networks.

Hamid Gharavi (F’92) received the Ph.D. degree from Loughborough University, United Kingdom, in 1980. He joined the Visual Communication Research Department at AT&T Bell Laboratories, Holmdel, New Jersey, in 1982. He was thenu transferred to Bell Communications Research (Bellcore) after the AT&T-Bell divestiture, where he became a consultant on video technology and a Distinguished Member of Research Staff. In 1993, he joined Loughborough University as a professor and chair of communication engineering. Since September 1998, he has been with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), U.S. Department of Commerce, Gaithersburg, Maryland. He was a core member of Study Group XV (Specialist Group on Coding for Visual Telephony) of the International Communications Standardization Body CCITT (ITUT). His research interests include smart grid, wireless multimedia, mobile communications and wireless systems, mobile ad hoc networks, and visual communications. He holds eight U.S. patents and has over 100 publications related to these topics. He received the Charles Babbage Premium Award from the Institute of Electronics and Radio Engineering in 1986, and the IEEE CAS Society Darlington Best Paper Award in 1989. He served as a Distinguished Lecturer of the IEEE Communication Society. In 1992 he was elected a Fellow of IEEE for his contributions to low-bit-rate video coding and research in subband coding for video applications. He has been a Guest Editor for a number of special issues, including Smart Grid: The Electric Energy System of the Future, Proceedings of the IEEE, June, 2011; a Special Issue on Sensor Networks & Applications, Proceedings of the IEEE, August 2003; and a Special Issue on Wireless Multimedia Communications, Proceedings of the IEEE, October 1999. He was a TPC Co-Chair for IEEE SmartGridComm in 2010 and 2012. He served as a member of the Editorial Board of Proceedings of the IEEE from January 2003 to December 2008. From January 2010 to December 2013 he served as Editor-in-Chief of IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON CAS for Video Technology. He is currently serving as the Editor-in-Chief of IEEE WIRELESS COMMUNICATIONS.

Appendix

flattening function calculus

Hereinafter, the calculus details of the flattening function of 1–level FDL is hold. By developing the function expression in (11) and using the Fourier Transform presented in (2), the obtained expression is given in (18).

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

Using that

for all a ∈ IR and IR is the set of real numbers, and applying the trigonometry formula

where a, b ∈ IR, successively, (19) is obtained.

Then, using the trigonometry formula

and using the expressions presented in (5), the obtained result is expressed in (20).

Then, giving

(20) can be expressed as in (21).

Finally, according to , we have

| (22) |

Consequently, the final expression of f (τ) is obtained as given in (4).

References

- 1.Teansri P, Hongpeechar B, Intarajinda R, Bhasaputra P, Pattaraprakorn W. Multi-scenarios of effective demand side management in Navanakorn industrial promotion zone. 2010:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin Z, Chongqing K, Kai L. Demand side management in China. IEEE PES General Meeting. 2010:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emec S, Kuschke M, Chemnitz M, Strunz K. Potential for demand side management in automotive manufacturing. 2013 4th IEEE/PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe, ISGT Europe 2013. 2013:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gharavi H, Hu B. Scalable Synchrophasors Communication Network Design and Implementation for Real-Time Distributed Generation Grid. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. (5):1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bera S, Misra S, Rodrigues JJ. Cloud Computing Applications for Smart Grid: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems. 2014;9219(c):1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fazeli A, Christopher E, Johnson CM, Gillott M, Sumner M. Investigating the effects of dynamic demand side management within intelligent Smart Energy communities of future decentralized power system; IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe; 2011. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salinas S, Li M, Li P. Multi-Objective Optimal Energy Consumption Scheduling in Smart Grids. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2012;4(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan Y, Qian Y, Sharif H, Tipper D. A Survey on Cyber Security for Smart Grid Communications. IEEE Communications Surveys and Tutorials. 2012;14(4):998–1010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang X, Misra S, Xue G, Yang D. Smart Grid The New and Improved Power Grid: A Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. 2012;14(4):944–980. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilil H, Belmoubarik S, Aniba G, Elgraini B, Maaroufi M. Non-uniform hierarchical modulation for wireless communication in smart grid; The 10th IEEE International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control; 2012. pp. 690–695. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belmoubarik S, Bilil H, Aniba G, Maaroufi M, Elgraini B. Dynamic assignment of renewable energy tokens in a collaborative microgrids; The 4th IEEE International Conference on Next Generation Networks & Services; 2012. pp. 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaira L. Achieving Demand Side Management with Appliance Controller Devices; Power Engineering Conference (UPEC), 2014 49th International Universities; 2014. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Logenthiran T. Demand side management in smart grid using heuristic optimization. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2012;3(3):1244–1252. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gan L, Wierman A, Topcu U, Chen N, Low SH. Real-time deferrable load control: handling the uncertainties of renewable generation; Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Future Energy Systems (e-Energy ’13); 2013. pp. 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papavasiliou A, Oren SS. Large-Scale integration of deferrable demand and renewable energy sources. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 2014;29:489–499. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiang Y, Member S, Liu J, Liu Y. Robust Energy Management of Microgrid With Uncertain Renewable Generation and Load. 2015:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta M, Gupta S. A Strategic Perspective of Development of Advanced Metering Infrastructure Based Demand Side Management (DSM) Model for Residential End User. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bae Hyoungchel, Yoon Jongha, Lee Yunseong, Lee Juho, Kim Taejin, Yu Jeongseok, Cho Sungrae, Bae H, Yoon J, Lee Y, Lee J, Kim T, Yu J, Cho S. User-friendly demand side management for smart grid networks; The International Conference on Information Networking 2014 (ICOIN2014); 2014. pp. 481–485. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zehir MA, Bagriyanik M. Demand Side Management potential of refrigerators with different energy classes; 2012 47th International Universities Power Engineering Conference (UPEC); 2012. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Z, Zhou S, Li J, Zhang XP. Real-time scheduling of residential appliances via conditional risk-at-value. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2014;5(3):1282–1291. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi P, Dong X, Iwayemi A, Zhou C, Li S. Real-Time Opportunistic Scheduling for Residential Demand Response. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. (1):227–234. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansen TM, Member GS, Roche R, Suryanarayanan S, Member S, Maciejewski AA, Siegel HJ. Heuristic Optimization for an Aggregator-Based Resource Allocation in the Smart Grid. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. :1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Bella G, Giarrè L, Ippolito M, Jean-Marie a, Neglia G, Tinnirello I. Modeling energy demand aggregators for residential consumers; Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Decision and Control; 2013. pp. 6280–6285. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gan L, Low S. Optimal Decentralized Protocols for Electric Vehicle Charging. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 2013;28(2):940–951. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galus MD, Wietor F, Andersson G. Incorporating valley filling and peak shaving in a utility function based management of an electric vehicle aggregator; IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ovalle A, Hably A, Bacha S. Optimal management and integration of electric vehicles to the grid: Dynamic programming and game theory approach; Industrial Technology (ICIT), 2015 IEEE International Conference on; 2015. pp. 2673–2679. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deb K, Pratap A, Agarwal S, Meyarivan T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation. 2002;6(2):182–197. [Google Scholar]

- 28.“Official website of ecole mohammadia d’ingenieurs http://www.emi.ac.ma/.”

- 29.Bilil H, Aniba G, Maaroufi M. Multiobjective optimization of renewable energy penetration rate in power systems. Energy Procedia. 2014;50:368–375. no. January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin Y-H, Tsai M-S. An Advanced Home Energy Management System Facilitated by Nonintrusive Load Monitoring With Automated Multiobjective Power Scheduling. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 2015;PP(99):1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graditi G, Luisa M, Silvestre D, Gallea R, Sanseverino ER. Heuristic-based shiftable loads optimal management in smart micro-grids. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics. 2014;3203(c):1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pipattanasomporn M, Kuzlu M, Rahman S, Teklu Y. Load Profiles of Selected Major Household Appliances and Their. Smart Grid, IEEE Transactions on (Volume:5, Issue: 2) 2014;5(2):742–750. [Google Scholar]