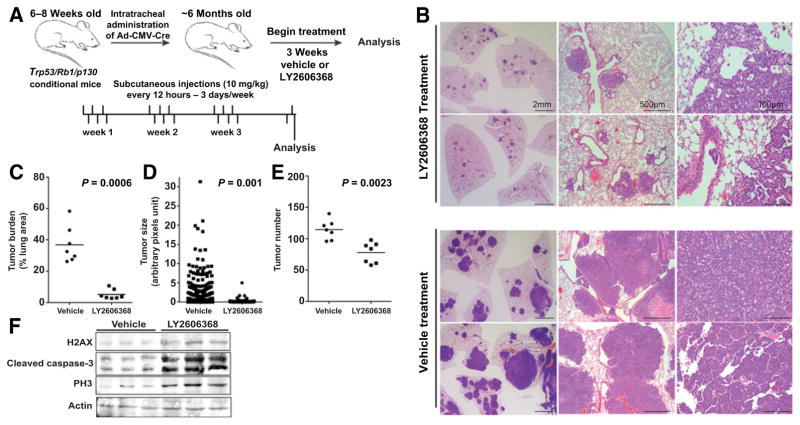

Figure 4.

LY2606368 causes tumor regression in a spontaneous genetically engineered mouse model of SCLC. A, Schematic representation of the treatment schedule in Trp53/Rb1/p130-knockout mice that develop SCLC. Mice (n = 7 per group) were treated with vehicle or LY2606368 (10 mg/kg, twice daily, days 1–3 of each 7-day cycle). B, Representative images (hematoxylin and eosin staining) of tumor burden in Trp53/Rb1/p130-knockout mice treated with vehicle control or LY2606368. Scale bars are indicated. C, Quantification of tumor burden as a percentage of lung area in Trp53/Rb1/p130-knockout mice treated with vehicle control or LY2606368 (n = 7 mice per group, one random lung section quantified per mouse). Per Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.006. D, Quantification of tumor size in Trp53/Rb1/p130-knockout mice treated with vehicle control or LY2606368 (n = 7 mice per group, one random lung section quantified per mouse). Per Mann–Whitney t test, P = 0.001. E, Quantification of tumors in Trp53/Rb1/p130-knockout mice treated with vehicle control or LY2606368 (n = 7 mice per group, one random lung section quantified per mouse). Per Mann–Whitney t test, P = 0.0023. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. F, Immunoblot analysis of phospho-H2AX (H2AX), cleaved caspase-3, and PH3 in lysates of resected tumors at treatment day 7 from the vehicle, LY2606368 treatment groups. Three animals were included per group. Actin was used as the loading control.