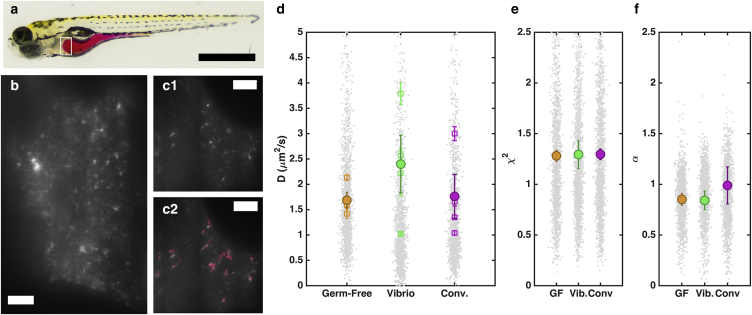

Figure 3.

Passive microrheology. (a) A larval zebrafish at five days postfertilization (dpf). The intestine is highlighted for illustration by orally gavaged phenol red dye. The voluminous intestinal bulb is evident at the anterior (left). Bar, 0.5 mm. (b) A subset of an optical section, corresponding roughly to the white rectangle region in (a), showing fluorescent tracer particles at the anterior of the gut. Bar, . (c) Another subset of a light-sheet field of view, showing particles (c1) and their trajectories (c2). Bar, . (d) Diffusion coefficients of nanospheres in the larval intestinal bulb. All data points are shown in gray; fewer than 3% are outside the plotted range. Average values within individual fish are shown as open squares, with error bars indicating mean ± SE. Averages across fish for each type, germ-free, monoassociated with a commensal Vibrio species, and conventionally colonized by microbes, are shown as solid circles, with error bars indicating mean ± SE ( fish each). (e) Reduced for the fit of the covariance-based estimator of D to the measured trajectories, for each fish type. (f) The scaling exponent, α, for the measured mean-squared-displacement as a function of time, for each fish type. For both (d) and (e), all data points are shown in gray, and solid symbols and error bars indicate the mean and SD of the mean, respectively, across fish of each type. The SD of α within each individual fish is ∼0.2 in all cases. For both (d) and (e), a value of one for or α is consistent with Brownian motion in a Newtonian fluid. To see this figure in color, go online.