Abstract

This study aims to investigate the effects of dependency and attachment in adjusting to the loss of a loved one by directly comparing the relative contribution of each to bereavement outcomes among midlife adults. Comparisons among attachment and dependency are made using models that control for attachment among three groups of bereaved adults (N=102): prolonged grievers (n=25), resolved grievers (n=41), and a married comparison group (n=36). Prolonged grievers displayed higher marginal means of dysfunctional detachment dependency and lower marginal means of healthy dependency compared to resolved grievers and married adults, even when controlling for attachment style. Findings suggest that attachment and dependency predict unique domains of grief outcome.

Keywords: dependency, detachment, attachment, bereavement, prolonged grief

The loss of a loved one can leave an enormous impact. Furthermore, confronting loss is deeply personal, varies widely between individuals, and is characterized by physical and mental health outcomes that depend on a variety of internal and external factors (Bonanno, 2009; Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2007). Individual differences in dependency and attachment have been of interest to researchers and clinicians from a range of theoretical orientations because of the compelling ways in which these two factors are associated with distinct bereavement outcomes (Bonanno et al., 2002; Carr et al., 2000; Denckla, Mancini, Bornstein, & Bonanno, 2011; Fraley & Bonanno, 2004). However, while studies have suggested that both dependency and attachment influence grief trajectory, few have directly investigated the ways in which these two aspects of interpersonal relating may differentially predict health outcomes among conjugally bereaved adults.

Though related, attachment and dependency refer to distinct constructs with unique correlates and health outcomes. However, the two terms are sometimes used interchangeably (Neyer, 2002), or in ways that reflect alternative definitions of the two constructs (Karakurt, 2012). As several researchers have noted, dependency behaviors (or the tendency to look to others for help or aid, even in situations where autonomous functioning is warranted) are context specific and change in response to particular environmental contingencies (Bornstein, 2011; Gewirtz, 1972). Attachment, on the other hand, is conceptually associated with experiences in enduring relationships that, once formed, persist throughout the lifespan. These experiences with early attachment figures are internalized as “internal working models” (for reviews, see Bretherton & Munholland, 1999; Pietromonaco & Feldman Barrett, 2000), or mental representations of self and other; are formed in the context of early parent-child relationships; and influence behavior, thought, and emotion throughout the lifespan. In summary, whereas dependency represents behaviors influenced by and directed toward a class of individuals, attachment behaviors are directed toward and reinforced by a particular individual.

Correlations between scores on measures of dependency and anxious attachment in adults tend to be in the .30 range (see Bornstein et al., 2003), though some studies report correlations as high as .64 (Alonso-Arbiol, Shaver, & Yarnoz, 2002), suggesting that although both attachment and dependency are related, they explain different features of interpersonal functioning. Furthermore, in both clinical and community samples, dependency and attachment have distinct correlates. For example, Bornstein (2006) found that dependent men are more likely to commit domestic violence when they fear that a relationship is in jeopardy, implying that attachment-related abandonment fears may predict risk for domestic violence primarily among those men who have high levels of interpersonal dependency. Alonso-Arbiol et al. (2002) found that anxious attachment and gender combined explained only 44% of the variance associated with emotional dependency and suggested that anxiously attached individuals may tend to report higher dependency in emotional contexts because of their preoccupation with abandonment coupled with a desire for closeness with others.

In addition, empirical evidence appears to support predictions that attachment and overdependence predict different health behaviors above and beyond the relative variance explained by either factor alone. For example, high levels of dependency tend to predict effective use of health care services among a sample of psychiatric inpatients (Fowler, Brunnschweiler, Swales, & Brock, 2005). However, attachment insecurities are associated with a reduced likelihood of initiating health care visits (Ciechanowski, Walker, Katon, & Russo, 2002; Feeney, 2000). Along somewhat different lines, Bornstein (2012) reviewed several findings suggesting that higher levels of trait dependency predict higher levels of abuse perpetration directed to intimate partners, with one study reporting dependency-abuse effect sizes corresponding to a d value of .87 for emotional dependency (Murphy, Meyer, & O’Leary, 1994). The same study reported that three indices of adult attachment (i.e., anxiety over abandonment, discomfort with closeness, and avoidance of dependency) yielded weaker relationships with abuse perpetration than did dependency scores.

In the specific context of bereavement, studies have demonstrated somewhat mixed results with respect to dependency and attachment. While several studies have linked both attachment and dependency with prolonged grief (Bonanno et al., 2002; Bruce, Kim, Leaf, & Jacobs, 1990; Osterweis, Solomon, & Green, 1984; Prigerson, Maciejewski, & Rosenheck, 2000), others have suggested that interpersonal dependency may also confer protective features when coping with loss (Blake-Mortimer, Koopman, Spiegel, Field, & Horowitz, 2003; Denckla et al., 2011). Similarly, while several studies have identified a link between insecure attachment and prolonged mourning (Field & Sundin, 2001; Fraley & Bonanno, 2004; Parkes & Weiss, 1983), other studies examining the relationship between attachment style and bereavement reported contradictory findings. For example, van der Houwen, Stroebe, Stroebe, Schut, and Meij (2010) noted that attachment avoidance contributed to symptomatic grief but that anxious attachment did not, after controlling for confounding variables. In related findings, Wijngaards-de Meij et al. (2007) found that while attachment insecurity and neuroticism both explained symptomatic grief symptoms, neuroticism explained a larger portion of variance in predicting adjustment to bereavement than did attachment insecurity. Further studies have also found that avoidance may have protective features (Bonanno, Keltner, Holen, & Horowitz, 1995; Mancini, Robinaugh, Shear, & Bonanno, 2009). Taken together, these findings suggest that when moderators of the attachment-bereavement relationship such as underlying traits were taken into account, the pathway between attachment and bereavement is altered.

THE PRESENT STUDY

The present study addresses a number of previously unexplored associations among dependency and attachment that may be linked with bereavement outcomes. First, our study employs a measure that taps three interrelated facets: healthy dependency, destructive overdependence, and dysfunctional detachment. The Relationship Profile Test (RPT; Bornstein et al., 2002) is a widely used measure of dependency-detachment that offers researchers the opportunity to assess both adaptive and maladaptive facets of this interpersonal style. Destructive overdependence is defined as inflexible help-seeking even in situations where autonomous functioning is warranted, and dysfunctional detachment involves deficits in the ability to cultivate social ties or engage in effective help-seeking behaviors (Birtchnell, 1987). Finally, healthy dependency is conceptualized as an adaptive blend of the ability to flexibly seek support without compromising social connectedness in the context of secure, autonomous functioning (Bornstein, 1998). Previous studies have investigated associations among these three facets of dependency and attachment style, noting expected convergent and divergent associations (Haggerty, Blake, & Siefert, 2010). Based on these studies, we expect to find a positive association between DO and DD and both avoidant and anxious attachment and a negative association between HD and avoidant and anxious attachment among married adults. We did not make predictions about the relationship between RPT facets and attachment dimensions among bereaved adults due to a lack of previous research in this area.

Second, we examine the possibility that dependency and attachment predict unique bereavement outcomes by comparing dependency among three study groups (prolonged grievers, resolved grievers, and a married comparison group) while controlling for attachment dimensions. Consistent with extant findings indicating that features of dependency-detachment predict certain domains of functioning in close interpersonal relationships better than do features of attachment (e.g., anxiety regarding abandonment, risk for partner abuse; see Bornstein, 2006), we hypothesize that dependency and detachment scores will predict prolonged grief even when the impact of attachment is controlled for statistically.

METHOD

Participants and Procedure

Bereaved participants were recruited from the New York City metropolitan area by distributing fliers, Internet advertisements, support group referrals, and sending letters directly to individuals identified as recently bereaved in public obituary notices. Married participants were recruited through Internet advertisements and online postings. Inclusion criteria required that participants be 65 years old or less and have experienced the loss of a spouse in the past 1.5 to 3 years. Participants were remunerated approximately $200 for taking part, and the study was approved by the institutional review board. Finally, all study participants received a packet of self-report questionnaires in the mail, which they completed prior to arriving at the study site. Once at the study site, participants delivered the questionnaire packet to study investigators and went on to complete semistructured interviews with a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology.

Among the enrolled participants, we identified a subsample matched on basic demographic indicators across the three study groups (married, resolved, and prolonged grievers). This resulted in a final group sample size of 102, consisting of 36 married participants (20 women, 16 men), 41 resolved grievers (21women, 20 men), and 25 prolonged grievers (11 women, 14 men). Age, gender, ethnicity, years of education, and income were broadly representative of the metropolitan area from which participants were recruited. The average age of participants was 47.41 (SD=6.93). The sample was split approximately equally between men (49%) and women (51%). Ethnicity of the full sample was 55% Caucasian, 28% African American, 4% Asian American, 10% Hispanic, and 3% “other.” Thirty-four percent of the sample had some college education, and an additional 27% had a bachelor’s degree. In addition, 17% had a high school education or less, and 22% had either some education at the master’s level or a doctoral degree. Finally, participants had been married an average of 15.33 years (SD=9.26), and the average reported family income was $63,084 (SD = $39,550). Tests of significance along these demographic indicators did not reveal significant differences among the three comparison groups, except in the category of family income, whereby the married group’s income was significantly higher than that of the bereaved participants.

Measures

Grief symptoms

Major depressive disorder (MDD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and grief symptoms were assessed using the structured clinical interview corresponding to DSM-IV criteria (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002). Specifically, trained interviewers administered items corresponding to symptoms of MDD (9 items, α=.84) and PTSD (14 items, α=.85). Interviewers also administered items related to grief-specific PTSD symptoms (avoidance of thoughts, feelings, and talking about the loss; avoidance of people and places related to the loss; and feelings of detachment from others) and symptomatic grief symptoms (a strong yearning for the deceased, preoccupation with thoughts about why or how the loss occurred, recurrent regrets or self-blame about one’s own behavior toward the deceased, recurrent regrets or blame about others’ behavior toward the deceased, frequent difficulty accepting the finality of the loss, utter aloneness, marked loneliness more days than not, difficulties developing new intimate relationships [not necessarily romantic], and a pervasive sense that life is meaningless or empty). These data were used to identify participants meeting criteria for prolonged grief according to criteria established by Prigerson et al. (1999). We selected these criteria because they have been most widely used among clinical samples and are consistent with the most recent consensus criteria for prolonged grief as suggested for inclusion in the DSM-5 (Prigerson et al., 2009). To assess interrater reliability, each interviewer coded a randomly selected set of five additional videotaped interviews; interrater reliability among researchers was very high (κ=.92).

Dependency-detachment

The Relationship Profile Test (Bornstein et al., 2002, 2003) is a 30-item self-report questionnaire that contains items describing attitudes toward the self and others with respect to dependency and detachment. Responses are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all true of me) to 5 (very true of me). The RPT yields three subscales of 10 items each: Destructive Overdependence (DO), Dysfunctional Detachment (DD), and Healthy Dependency (HD). Sample items include “I am most comfortable when someone else takes charge” (DO); “When someone gets too close to me, I tend to withdraw” (DD); and “Being independent and self-sufficient are very important to me” (HD). In the present sample, Cronbach’s alphas for DO, DD, and HD were .86, .76, and .76, respectively.

Attachment

The Experiences in Close Relationships–Revised (ECR-R; Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000) is a 36-item questionnaire that assesses self-reported adult romantic attachment anxiety (model of self) and avoidance (model of others), developed using a combination of classical psychometric techniques and item response theory. The ECR-R has shown adequate psychometric properties across varying populations (Sibley & Liu, 2004). Participants’ responses are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items include “I talk things over with others” and “I do not often worry about being abandoned.” Some items are reverse scored in order to improve reliability (e.g., the second sample item in the previous sentence). Directions administered to participants stated “We are interested in how you generally experience relationships, not just in what is happening in a current relationship.” In the present sample, Cronbach’s alphas for attachment anxiety and avoidant attachment were .92 and .75, respectively.

RESULTS

First, we conducted comparisons between the matched group used in this study and the original sample along the two measures of interest (the RPT and the ECR-R) to test for the possibility that our sample matching procedures had introduced some unintended bias. We found no significant differences between the groups along subscales of the RPT (two-tailed t values for DO, DD, and HD, respectively, were −0.60 [df=194, p=.55, −1.48 [df=194, p=.14], and 1.20 [df=194, p=.23]). Next, we made similar comparisons between the matched subsample and the original sample along the two dimensions of attachment, finding no significant differences between the two groups in avoidant attachment (t=−1.44, df=194, p=.15) but obtaining significant differences between the matched and unmatched group along the anxious attachment dimension (t=−2.48, df=194, p=.01). Further exploration revealed that the mean anxious attachment score for the subgroup included in the analysis in this study was higher (M=3.28, SD=1.30) than that in the excluded group (M=2.84, SD=1.16). However, after conducting a second ANCOVA to control for gender effects, this significant difference between matched and unmatched groups was no longer present, F(1, 87)=1.15, p=.24. We therefore proceeded to control for gender in subsequent analyses. We also noted that there were significant differences between the study groups in income level, with the married group reporting a higher income than both the bereaved groups. This difference between study groups is best explained by the likelihood that the married group represents a family income with two potential wage earners while that of the bereaved group represents only one wage earner.

Then correlation coefficients between the RPT and ECR-R attachment dimensions were analyzed; these are presented separately for the three study groups in Table 1. As expected, anxious attachment was significantly and positively correlated with DO among resolved (r=.55, p<.01) and married participants (r=.55, p<.01). However, anxious attachment was not significantly associated with DO among the prolonged grief group (r=.23, ns). Similarly, anxious attachment was negatively correlated with HD among married (r=−.60, p<.01) and resolved adults (r=−.67, p<.01). A similar negative correlation was noted among prolonged grievers, but the association was not significant (r=−.21, ns). Finally, anxious attachment was positively correlated with DD among married adults (r=.60, p<.01), but the correlation was not significant among the resolved group (r=.11, ns) or prolonged grievers (r=−.09, ns).

TABLE 1.

RPT and ECR-R Correlations Among Prolonged Grievers, Resolved Grievers, and Married Adults.

| Attachment dimension | Prolonged grief (n=25)

|

Resolved grief (n=41)

|

Married (n=36)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DO | DD | HD | DO | DD | HD | DO | DD | HD | |

| Anxious | .23 | −.09 | −.21 | .55** | .11 | −.67** | .55** | .60** | −.60** |

| Avoidant | .11 | .44* | −.37 | .26 | .42** | −.50** | .48** | .56** | −.73** |

Note. RPT=Relationship Profile Test; ECR-R=Experiences in Close Relationships–Revised; DO= Destructive Overdependence; DD=Dysfunctional Detachment; HD=Healthy Dependency.

p<.05;

p<.01.

Correlations between the avoidant subscale of the ECR-R and the RPT dimensions are also summarized in Table 1. Avoidant attachment was significantly correlated with DO among married adults (r=.48, p<.01), but not among resolved grievers (r=.26, ns) or prolonged grievers (r=.11, ns). Avoidant attachment was positively correlated with DD among the married, resolved, and prolonged grief groups (r=.56, p<.01; r=.42, p<.01; and r=.44, p<.01, respectively). Finally, avoidant attachment was negatively correlated with HD among married adults (r=−.73, p<.01) and resolved grievers (r=−.50, p<.01). No significant relationship was noted between HD and avoidant attachment among prolonged grievers (r=−.37, ns).

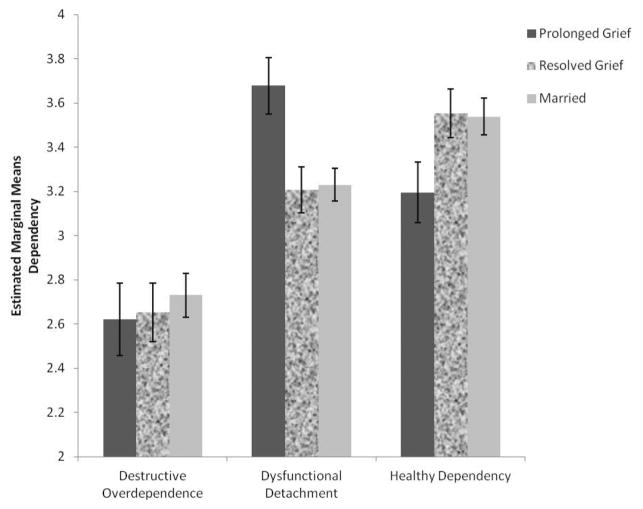

Finally, results of the ANCOVA assessing between-group differences in dependency facets among the three study groups while controlling for gender and attachment are summarized below. We first conducted an ANCOVA with both attachment anxiety and avoidance included in the same model with gender as a covariate but failed to find a significant difference. We then conducted two more separate ANCOVAs with attachment anxiety and avoidance entered in separate models. While the first model with attachment avoidance entered did not yield a significant association, the second model that included attachment anxiety did suggest significant associations. Table 2 shows the estimated marginal means and standard errors in RPT scores and the resulting F tests and pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments (where appropriate) for this second model. As hypothesized, RPT-derived DD and HD scores were associated with grief status even when controlling for attachment anxiety. Specifically, prolonged grievers had significantly higher marginal DD means (M=3.67, SE=.14) compared to resolved grievers (M=3.20, SE=.11) and married adults (M=3.23, SE=.11). Also consistent with the study hypotheses, prolonged grievers had significantly lower marginal HD means (M=3.20, SE=.11) compared to married adults (M=3.54, SE=.09). Contrary to study hypotheses, there were no significant differences in DO marginal means among the three study groups. Results are summarized graphically in Figure 1.

TABLE 2.

Estimated Marginal Means for Dependency With Gender and Attachment Anxiety as Covariates for Prolonged Grievers, Resolved Grievers, and Married Adults.

| Variables | n | M (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Destructive Overdependence | ||

| Prolonged grief | 25 | 2.62 (.16) |

| Resolved grief | 41 | 2.65 (.12) |

| Married adults | 36 | 2.73 (.13) |

| F test | F(2, 97) = .157 (ns, ) | |

| Pairwise comparisons | ns | |

| Dysfunctional Detachment | ||

| Prolonged grief | 25 | 3.67 (.14) |

| Resolved grief | 41 | 3.20 (.11) |

| Married adults | 36 | 3.23 (.11) |

| F test | F(2, 97) =4.28* (p = .017, ) | |

| Pairwise comparisons | 1 > 3, 2 | |

| Healthy Dependency | ||

| Prolonged grief | 25 | 3.20 (.11) |

| Resolved grief | 41 | 3.55 (.09) |

| Married adults | 36 | 3.54 (.09) |

| F test | F(2, 97) =3.84* (p = .025, ) | |

| Pairwise comparisons | 1 < 2 | |

Note. Only significant pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments (p<.05) are provided.

p<.05.

FIGURE 1.

Estimated marginal means for dependency with gender and attachment anxiety as covariates.

DISCUSSION

Our hypotheses regarding the association between attachment and dependency were largely supported and consistent with associations reported in previous studies. For example, Haggerty et al. (2010) found that both DO and DD were positively and significantly associated with ECR-R-assessed anxious attachment (rs=.46 and .21, respectively) and avoidant attachment (rs=.17 and .44, respectively). In the study reported here, a similar pattern of positive association between DO and DD and anxious attachment (rs=.55 and .60, respectively), as well as avoidant attachment (rs=.48 and .56, respectively), was found among married adults. Finally, HD was negatively associated with both anxious and avoidant attachment among married adults, similar to the association noted among college students in Haggerty et al.’s (2010) study.

As hypothesized, dependency and detachment showed markedly different patterns of associations among individuals experiencing prolonged grief, a bereaved group without clinical symptoms, and a married comparison group, helping predict grief trajectory above and beyond the effects of attachment style. Specifically, HD was significantly related to a course of grieving free of clinical mental health symptoms, even when taking into consideration the amount of variance that can be explained by anxious attachment style. Conversely, higher levels of DD were significantly associated with prolonged grief, even when controlling for the amount of variance in this association that can be explained by anxious attachment. These results suggest that dependency and attachment anxiety are associated with unique aspects of interpersonal functioning that share some but not all of their explained variance in predicting functioning after the loss of a spouse.

Our findings diverged from hypotheses in two important areas. First, DO did not predict grief trajectory above and beyond attachment style. This was surprising given that previous studies have identified an association between overdependence and prolonged grief (Bonanno et al., 2002; Johnson, Zhang, Greer, & Prigerson, 2007). To better understand this finding, we compared the language of dependency items between studies and found that differences among assessment instruments made it difficult to draw firm conclusions. However, a speculative conclusion suggests that there may be differences in grief outcome depending on the specific type of dependency being assessed. For example, Bonanno et al. (2002) assessed dependency among bereaved adults by targeting emotional reliance on the deceased spouse, while the RPT assesses dependency across a broad array of domains hypothesized to be impacted by this personality style. While healthy dependency and dysfunctional detachment distinguish prolonged and resolved grievers, the full impact of overdependence may be more nuanced. However, it appears that different types of maladaptive dependency can reliably distinguish prolonged grievers from resolved grievers, whether dependency is assessed with respect to the respondent’s specific feelings toward a particular spouse (Bonanno et al., 2002) or assessed using a measure of dependent personality functioning more broadly, as in the current study. Second, we failed to find that dependency predicted grief outcome when controlling for avoidant attachment. Though speculative, it may be that avoidance and facets of dependency share more variance in predicting grief outcome, as previous studies have noted the potentially protective features associated with avoidance and dependency during bereavement (Bonanno, Keltner, Holen, & Horowitz, 1995; Denckla et al., 2011; Mancini et al., 2009).

Theoretical Implications

Findings suggest that dependency and detachment provide unique information regarding resilience and coping at midlife, beyond that derived from adult attachment style. Results lend some support to Gewirtz’s (1972) functional conceptualization of dependency and Bornstein’s (2011) cognitive/interactionist model, which proposes that dependent behaviors are influenced by cues and reinforcements from any one class of individuals. Specifically, when individuals are bereaved and adjusting to the loss of a spouse, it may be that the particular pattern of reinforcers established by the presence of individuals perceived to be sources of support and aid exerts a greater influence on clinical pathology than the pattern of reinforcers established in the context of the lost partnership or influenced by internal representations of early attachment figures.

Because the study findings were generated using a cross-sectional design, causality cannot be determined definitively. That is, it is impossible to disentangle the potentially recursive effects between the bereavement process and personality self-attribution. One implication of this is that the trauma of loss itself can lead to personality reorganization (either positive or negative), and in fact there is a substantial literature devoted to the concept of posttraumatic growth (Tedeschi & Kilmer, 2005). It is possible that the association found in this study between HD and resolved grieving could be a product of posttraumatic growth, such that this particular group of individuals perceived improved well-being as a result of the personal growth they experienced after coping with the trauma of a lost loved one. This possibility rests on the assumption that level and expression of interpersonal dependency may sometimes be amenable to change, even in adulthood, as bereaved individuals reorganize their personality orientation as a direct result of the loss.

However, an alternative theory suggests that mood-repair motivation can guide retrospective self-imagery recall. McFarland and Buehler (2012) summarize four related experiments demonstrating that participants report greater personal growth after negative mood states are induced than after neutral moods are induced. The authors suggested that both current mood and mood-repair motivations influenced attitudes toward self-attributed growth, even when controlling for actual change over time. Although this does not rule out the possibility that individuals may experience personality reorganization as a result of posttraumatic growth, the results do present some conceptual concerns that can only be parsed out through experimental or longitudinal research designs.

Diagnostic, Assessment, and Treatment Implications

The present findings suggest that assessing both adaptive and maladaptive dependency in the context of bereavement may be useful not only in predicting adjustment to loss, but also in informing interventions to ameliorate the potential clinical course of bereavement. Furthermore, the findings suggest that attachment-related features of interpersonal functioning may have a reduced impact on the bereavement process when dependency-related functioning is taken into account. With respect to dependency, the results complement and extend previous findings suggesting that there are positive health effects associated with dependency, including increased compliance with medical care and increased engagement in support (Bonanno, 2009; Bornstein, 1998, 2005). The results also suggest that facilitating social connectedness may be particularly important for midlife adults coping with the loss of a significant other, so interventions should include a component that facilitates the development of healthy dependency.

Our results also have implications for more specific therapeutic strategies. Clinical interventions for prolonged grief entail a specific focus on avoidance behaviors, in addition to addressing depressive and posttraumatic features of the clinical presentation. Clinically validated treatments include cognitive grief therapy (CGT), which is a combination of interpersonal therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy to address loss-specific distress (Shear, Frank, Houck, & Reynolds, 2005). Findings from this study lend support to recommended interventions that target self-schemas through cognitive restructuring (see, e.g., Bornstein, 2005), in addition to interventions designed to modify the maladaptive interpersonal patterns that are a focus of treatment in CGT.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of this study should be taken into consideration when interpreting the present findings. Most importantly, dependency and attachment were both measured by self-report and did not include an observational or behavioral assessment. Although studies consistently find that self-assessed dependency does predict a broad array of real-world behaviors (Bornstein, 2011), the present findings are limited in the extent to which we can make reliable predictions about the role of dependent personality traits in the course of bereavement. Future studies should investigate the mechanisms by which adaptive dependency may function as a protective factor following conjugal loss through longitudinal designs that capture variables related to pre-loss personality functioning. Alternatively, future research can utilize designs that include observational or knowledgeable informant ratings of dependency- and attachment-related behaviors.

In addition, the modest sample size limits the extent to which we can draw firm conclusions regarding the generalizability of our findings. However, a power analysis does suggest that our sample size exceeded the minimum necessary to achieve an effect size of 1.00 at 80% power. Results therefore suggest that while the sample size included in this analysis was modest, it was sufficient to detect group differences consistent with previous studies in the literature. Finally, given that we did identify income differences between the two study groups, it would have been ideal to control for income in our models, but we were unable to do so because of the loss of power when including income as a covariate in our models due to missing income data among our prolonged grief group.

In conclusion, the present results suggest that adults suffering from prolonged grief may endorse greater detachment and less healthy dependency compared to adults presenting with resolved grief, above and beyond the effects that can be explained by attachment. Our findings support the hypothesis that attachment and dependency predict distinct aspects of interpersonal functioning, and these results have implications for both theory and practice. This pattern is consistent with previous investigations suggesting that dependency is best conceptualized as a multifaceted construct (Bornstein, 2005; Pincus & Wilson, 2001) comprised not only of resilience and risk factors, but also features that are distinct from attachment patterns. Furthermore, our findings extend the literature on qualities of the marital relationship as predictors of prolonged grief.

Biographies

Christy A. Denckla is a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology at the Derner Institute of Advanced Psychological Studies, Adelphi University, and a Clinical Fellow in Psychology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School. Her research has focused on individual differences in response to aversive life events, including bereavement, interpersonal trauma, and daily stressors.

Robert F. Bornstein is a professor of psychology at Adelphi University. He has published numerous articles and book chapters on personality dynamics, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment.

Anthony D. Mancini is an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at Pace University. His research and scholarly interests have focused on the different ways that people respond to life events and acute adversity.

George A. Bonanno is a professor of clinical psychology and director of the Loss, Trauma, and Emotion Lab at Columbia University’s Teachers College. His interests center on the question of how human beings cope with loss, trauma, and other forms of extreme adversity, with an emphasis on resilience and the salutary role of flexible emotion regulatory processes.

Contributor Information

CHRISTY A. DENCKLA, Gordon F. Derner Institute of Advanced Psychological Studies, Adelphi University, Garden City, New York, USA

ROBERT F. BORNSTEIN, Gordon F. Derner Institute of Advanced Psychological Studies, Adelphi University, Garden City, New York, USA

ANTHONY D. MANCINI, Department of Psychology, Pace University, New York, New York, USA

GEORGE A. BONANNO, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, New York, USA

References

- Alonso-Arbiol I, Shaver P, Yarnoz S. Insecure attachment, gender roles, and interpersonal dependency in the Basque country. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:479–490. [Google Scholar]

- Birtchnell J. Attachment-detachment, directiveness-receptiveness: A system for classifying interpersonal attitudes and behaviour. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;60:17–27. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1987.tb02713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake-Mortimer J, Koopman C, Spiegel D, Field N, Horowitz M. Perceptions of family relationships associated with husbands’ ambivalence and dependency in anticipating losing their wives to metastatic/recurrent breast cancer. Journal of Loss & Trauma. 2003;8:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. The other side of sadness: What the new science of bereavement tells us about life after loss. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Keltner D, Holen A, Horowitz MJ. When avoiding unpleasant emotions might not be such a bad thing: Verbal-autonomic response dissociation and midlife conjugal bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:975–989. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Lehman DR, Tweed RG, Haring M, Sonnega J, … Nesse RM. Resilience to loss and chronic grief: A prospective study from preloss to 18-months postloss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:1150–1164. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.5.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein RF. Depathologizing dependency. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186:67–73. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199802000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein RF. The dependent patient: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2005;36:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein RF. The complex relationship between dependency and domestic violence: Converging psychological factors and social forces. American Psychologist. 2006;61:595–606. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein RF. An interactionist perspective on interpersonal dependency. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;20:124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein RF. Illuminating a neglected clinical issue: Societal costs of interpersonal dependency and dependent personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68:766–781. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein RF, Geiselman KJ, Eisenhart EA, Languirand MA. Construct validity of the Relationship Profile Test: Links with attachment, identity, relatedness, and affect. Assessment. 2002;9:373–381. doi: 10.1177/1073191102238195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein RF, Languirand MA, Geiselman JA, Creighton MA, West HA, Gallagher EA, Eisenhart EA. Construct validity of the Relationship Profile Test: A self report measure of dependency-detachment. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2003;80:64–74. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8001_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Munholland KA. Internal working models in attachment relationships: A construct revisited. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Kim K, Leaf PJ, Jacobs S. Depressive episodes and dysphoria resulting from conjugal bereavement in a prospective community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:608–611. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.5.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, House JS, Kessler RC, Nesse RM, Sonnega J, Wortman C. Marital quality and psychological adjustment to widowhood among older adults: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Gerontology, Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2000;55:S197–S207. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.4.s197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski PS, Walker EA, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Attachment theory: A model for health care utilization and somatization. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:660–667. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000021948.90613.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denckla CA, Mancini AD, Bornstein RF, Bonanno GA. Adaptive and maladaptive dependency in bereavement: Distinguishing prolonged and resolved grief trajectories. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;51:1012–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA. Implications of attachment style for patterns of health and illness. Child: Care, Health & Development. 2000;26:277–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2000.00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field N, Sundin E. Attachment style in adjustment to conjugal bereavement. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2001;18:347–361. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JC, Brunnschweiler B, Swales S, Brock J. Assessment of Rorschach dependency measures in female inpatients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2005;85:146–153. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8502_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Bonanno GA. Attachment and loss: A test of three competing models on the association between attachment-related avoidance and adaptation to bereavement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:878–890. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:350–365. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz JL. Attachment, dependence, and a distinction in terms of stimulus control. In: Gewirtz JL, editor. Attachment and dependency. Washington, DC: V. H. Winston & Sons; 1972. pp. 139–177. [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty G, Blake M, Siefert CJ. Convergent and divergent validity of the Relationship Profile Test: Investigating the relationship with attachment, interpersonal distress and psychological health. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2010;66:339–354. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Zhang B, Greer JA, Prigerson HG. Parental control, partner dependency, and complicated grief among widowed adults in the community. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195:26–30. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000252009.45915.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakurt G. The interplay between self esteem, feelings of inadequacy, dependency, and romantic jealousy as a function of attachment processes among Turkish college students. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2012;34:334–345. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini AD, Robinaugh D, Shear K, Bonanno GA. Does attachment avoidance help people cope with loss? The moderating effects of relationship quality. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:1127–1136. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland C, Buehler R. Negative moods and the motivated remembering of past selves: The role of implicit theories of personal stability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102:242–263. doi: 10.1037/a0026271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyer FJ. The dyadic interdependence of attachment security and dependency: A conceptual replication across older twin pairs and younger couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2002;19:483–503. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Meyer SL, O’Leary KD. Dependency characteristics of partner assaultive men. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:729–735. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterweis M, Solomon F, Green M. Bereavement: Reactions, consequences, and care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes CM, Weiss RS. Recovery from bereavement. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco PR, Feldman Barrett L. The internal working models concept: What do we really know about the self in relation to others? Review of General Psychology. 2000;4:155–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus AL, Wilson KR. Interpersonal variability in dependent personality. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:223–251. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Aslan M, Goodkin K, … Maciejewski PK. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6:e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Rosenheck RA. Preliminary explorations of the harmful interactive effects of widowhood and marital harmony on health, health service use, and health care costs. The Gerontologist. 2000;40:349–357. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Jacobs SC, Reynolds CF, Maciejewski PK, Davidson JR, … Zisook S. Consensus criteria for traumatic grief: A preliminary empirical test. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;174:67–73. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, Reynolds CF. Treatment of complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:2601–2608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley CG, Liu JH. Short-term temporal stability and factor structure of the revised Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR-R) measure of adult attachment. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36:969–975. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370:1960–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Kilmer RP. Assessing strengths, resilience, and growth to guide clinical interventions. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2005;36:230–237. [Google Scholar]

- van der Houwen K, Stroebe M, Stroebe W, Schut H, Meij LW. Risk factors for bereavement outcome: A multivariate approach. Death Studies. 2010;34:195–220. doi: 10.1080/07481180903559196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijngaards-de Meij L, Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W, van den Bout J, van der Heijden P, Dijkstra I. Neuroticism and attachment insecurity as predictors of bereavement outcome. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:498–505. [Google Scholar]