Abstract

Objective

Prostate cancer mortality rates have decreased over recent decades, but racial disparities in prostate cancer survival still present as a serious challenge. These disparities may be impacted by age; in fact, African American men younger than age 65 have prostate cancer mortality rates nearly three times greater than that of White men. Therefore, a systematic literature review was conducted in Medline and EMBASE databases focusing on articles comparing survival and mortality rates for prostate cancer patients across age and race.

Design

Articles included were based on the following criteria: 1) included African American and White prostate cancer patients residing in the United States; 2) measured racial disparities across distinct age categories with at least one category below and one above age 65; 3) addressed racial disparities in terms of overall survival or mortality.

Results

Twenty eight articles compared survival and mortality disparities between African American and White prostate cancer patients across different age categories. Of the 28 articles, 19 articles (68%) showed disparities decreased with age, eight articles (29%) showed disparities constant with age, and one article (3%) showed disparities increased with age.

Conclusions

More often the survival and mortality gap between African American and White prostate cancer patients decreases with age. Additional studies are needed to elucidate other factors that may influence racial disparities in prostate cancer patients. These results provide insight into the racial disparities in prostate cancer and suggest more resources should be directed towards decreasing the disparity gap in younger prostate cancer patients.

Keywords: systematic review, prostatic neoplasms, healthcare disparities, African American Continental Ancestry Group, European Continental Ancestry Group, middle aged, aged

Background

While overall mortality rates of prostate cancer have decreased over the past two decades, racial disparities in prostate cancer survival still remain a critical issue. African American men are two and a half times as likely to die of prostate cancer as any other race (ACS 2015; Siegel et al. 2014). However, a recent Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) statistics review found that among prostate cancer patients younger than 65 years of age, African Americans have a mortality rate nearly three times that of Whites (Howlader et al. 2014). Furthermore, the American Cancer Society (2015) states that although prostate cancer incident rates in men older than 65 years have decreased by 2.8% yearly from 2007 to 2011, the incidence rates for those younger than 65 have remained stable.

The racial disparity can be explained by inherent differences in the genetic makeup (Shavers and Martin 2002) and tumor biology (Wallace et al. 2008) of African American and White prostate cancer patients, as well as by differences in access to health care and treatment receipt (Taksler, Keatin and Cutler 2012). Differences in gene expression have been linked to differences in tumor biology between the races as well (Shavers and Martin 2002). Studies have also shown that more African American patients hold lower socioeconomic status (Hoffman et al. 2001), and receive watchful waiting (Shavers et al. 2004) and less aggressive treatment for prostate cancer more often than White patients (Taksler, Keatin and Cutler 2012).

African American men have been found to present at a younger age, with higher prostate-specific antigen (PSA), worse tumor grading, and more advanced stages of prostate cancer than White men (Hoffman 2001). Powell et al. (1999) found more pronounced differences between African American and White men in the 50–59 age group than in older age groups in terms of PSA levels, tumor grading, advanced disease, and recurrence rates. Powell et al. (2010) showed that prostate cancer may become distant metastatic disease at a rate of 4:1 starting at age 40 to 49 years, and concluded that prostate cancer may grow more rapidly or transform into an aggressive form earlier in African American men compared with White men.

While there is an abundance of literature showing differences in mortality between African American and White prostate cancer patients, there is far less literature available that examines the racial disparity gap as patients age. Therefore, a systematic literature review is necessary to assess whether differences in survival or mortality between African American and White prostate cancer patients widen, narrow, or stay constant with increasing age.

Methods

A systematic review of available literature was conducted with two searches performed on the EMBASE and Medline databases. The search string, developed under the guidance of the University of Maryland Baltimore reference librarian, includes the words “African American”, “Caucasian”, “disparities”, “prostatic neoplasms” and “survival”. The full search string is included in the addendum. Articles were limited to English, human subjects and journal articles, and included all articles within the database up until July 2014.

The articles were examined and kept for the study based on the following selection criteria: 1) articles included data on African American and White prostate cancer patients residing in the United States; 2) articles compared racial disparities across distinct age categories with at least one category below and one above age 65; 3) articles addressed racial disparities in terms of overall survival and mortality rates of prostate cancer patients.

The titles and abstracts of the search results were screened to determine relevance and inclusion into the study. If an article’s relevance could not be determined solely by the title and abstract, then the full article was retrieved to determine the relevance. One author participated in the article abstraction process. Both authors met to discuss each article included in the final selection. Survival and mortality statistics were extracted from articles in order to compare racial disparities in prostate cancer outcomes.

Results

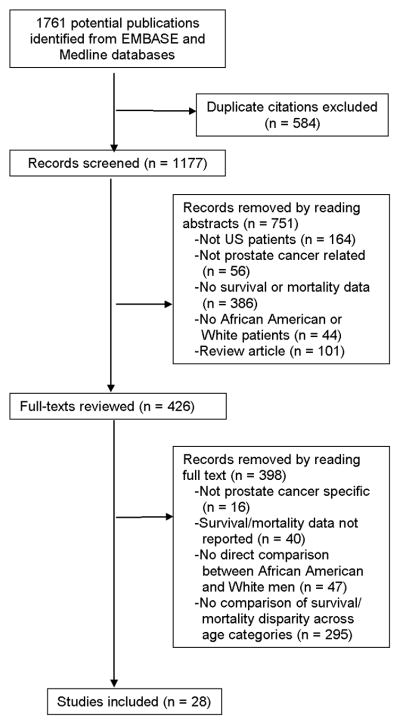

The literature searches in the Medline and EMBASE databases produced 1,177 articles, as seen in Figure 1. Based on the inclusion criteria, 28 articles were selected as relevant to the study, as seen in Figure 1 and Table 1. These studies measured racial disparities in prostate cancer patients through survival and mortality data, and compared the disparities across increasing age categories.

Figure 1.

Diagram of selection process for articles included in the systematic review

Table 1.

Summary of analysis of studies reporting overall survival and mortality disparities included in review

| SURVIVAL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author Year | Outcome | Sample | Data Source | Age Range | Age Comparisons | Staging | Racial disparity |

| Austin 199010 | Median survival (years) | 117 | NYHSC + KCHC* | 49–92 | (<60) vs (>60) | Stage B–D | Decreases with age |

| Austin 199311 | Survival at 5 years (percent) | 914 | SEER* | 45–91 | (<60) vs (>60) | Stage B–D† | Decreases with age |

| Fowler 200012 | Cause specific survival (months after diagnosis) | 920 | VAMC* | Not reported | (<70) vs (>70) | Stage T1b-2 | Decreases with age |

| Matzkin 198313 | Overall survival | 119 | Not reported* | 49–86 | (<60) vs (>60) | Stage D2 | Decreases with age |

| Mebane 199014 | 5 year relative survival rate (percent) | 7.4% total Black population; 5% total White population | SEER* | Not reported | (50–59) (60–64) (65–69) (70–74) (75–79) (80–84) (85+) | All | Decreases with age |

| Pienta 199515 | Overall survival (months after diagnosis) | 12907 | SEER* | Not reported | (50) vs (55) vs (60) vs (65) vs (70) vs (75) | All | Decreases with age |

| Powell 199516 | Overall survival (months after diagnosis) | 741 | VAMC* | 43–96 | (<65) vs (>65) | All | Decreases with age |

| Kant 199217 | 5 year relative survival rate (proportion) | 127554 | SEER* | 19+ | (<65) vs (65–74) vs (75+) | All | Constant across age |

| Pulte 201218 | 5 year relative survival | Approx. 30 million | SEER* | Not reported | (15–64) vs (65+) | Not Reported | Constant across age |

| Walker 199519 | 5 year relative survival rate | Not reported | SEER* | Not reported | (<65) vs (>65) | Not Reported | Constant across age |

| Wingo 199820 | 5 year relative survival rate (percent) | 137888 | SEER* | Not reported | (45–54) (55–64) (65–74) (75+) | All | Constant across age |

| Penson 200721 | 5 year survival rate | Not Reported | SEER* | Not reported | (45–54) (55–64) (65–74) (75+) | All | Increases with age |

| MORTALITY | |||||||

| AuthorYear | Outcome | Sample | Data Source | Age Range | Age Comparisons | Staging | Racial Disparity Gap |

| Brawley 201222 | Mortality rates (per 100,000) | Not reported | SEER* | 40+ | (40–44) (45–49) (50–54) (55–59) (60–64) (65–69) (70–74) (75–79) (80–84) (85+) | Not Reported | Decreases with age |

| CDC 199223 | Death Rates (per 100,000) | Not reported | SEER* | 50+ | (50–54) (55–59) (60–64) (65–69) (70–74) (75–79) (80–84) (85+) | Not Reported | Decreases with age |

| Cheng 200924 | Deaths (percent) | 102691 | SEER* | 45+ | (45–54) (55–64) (65–74) (75–84) (85+) | All | Decreases with age |

| Chu 200325 | Mortality rates | 10% US Population | SEER* | 50–84 | (50–59) (60–69) (70–79) (80–84) (85+) | All | Decreases with age |

| Cowen 199426 | Annual mortality rates | Not reported | SEER* | 30–80 | (50) vs (55) vs (60) vs (65) vs (70) vs (75) vs (80) | Not reported | Decreases with age |

| Ernster 197727 | Mortality rates | 3258 | Alameda* | 50+ | (50–59) (60–64) (65–69) (70–74) (75+) | Not reported | Decreases with age |

| Ernster 197828 | Annual mortality rates | 106519 | Alameda* | 50+ | (50–59) (60–64) (65–69) (70–74) (70–79) (85+) | Not reported | Decreases with age |

| Fulton 200129 | Mortality rate | Not reported | RI, SEER* | 30+ | (30–39) (40–49) (50–59) 60–69) (70–79) (80+) | All | Decreases with age |

| Garfinkel 199430 | Mortality rates (per 100, 000) | US population | NCI* | Not reported | (<65) vs (>65) | Not reported | Decreases with age |

| Hsing 199431 | Mortality rates | Not reported | Nat Center for Health Stats* | 40+ | (40–49) (50–54) (55–59) (60–64) (65–69) (70–74) (75–79) (80–84) (85+) | Not reported | Decreases with age |

| Robbins 200032 | Death rate ratio | 23334 | SEER* | 35+ | (<65) vs (>65) | All | Decreases with age |

| Soto-Salgado 201233 | Mortality rate (per 100,000) | Not reported | SEER + PR* | 45+ | (45–54) (55–64) (65–74) (75–84) (85+) | Not reported | Decreases with age |

| Datta 201134 | Odds ratio for mortality | 5% US Census Microsample Data | US Census | 40–89 | (40–64) vs (65–74) vs (75+) | All | Constant across age |

| Merrill 199735 | Percent mortality (years after diagnosis) | 10% US population | SEER* | 50+ | (50–69) vs (70+) | All | Constant across age |

| Piffath 200136 | Mortality rate (per 100,000) | Not reported | Vital Stats of US Reports | 40+ | (60–69) (70–79) (80+) | Not reported | Constant across age |

| Sarma 200237 | Lifetime risk for dying | 10% US Population | SEER* | Not reported | (50) vs (60) vs (70) | All | Constant across age |

Alameda: Alameda County; KCHC: Kings County Hospital Center; NYHSC: New York Health Science Center; Nat Center for Health Stats: National Center for Health Statistics; NCI: National Cancer Institute Cancer Statistics Review; PR: Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry; RI: Rhode Island Cancer Registry; SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; VAMC: Veterans Affairs Medical Center

554 cases lack report on staging

Population-Based Registry VS Single Institution-based Registry Studies

Of the 28 articles included in the study, 24 articles (86%) were population-based registry studies (Table 1). More specifically, eighteen population-based registry studies used data from the SEER database. The non-SEER population-based registry studies included data from the National Center for Health Statistics (Hsing and Devesa 1994), the Rhode Island cancer registry (Fulton 2001), and Alameda County registries (Ernster et al. 1997, 1998). Three of the 28 articles were single institution-based registry studies, which included data from Veterans Affairs (Fowler et al. 2000; Powell, Schwartz and Hussain 1995) and New York hospitals (Austin et al. 1990) (Table 1). Matzkin et al. (1993) did not specify the data source.

Study Characteristics

The articles collected had publication dates ranging from 1977 to 2012. The population-based registry studies involved a range of sample sizes, from 914 patients (Austin and Convery 1993) to 10% of the US population (Chu, Tarone, and Freeman 2003), as seen in Table 1. The single institution-based registry studies involved sample sizes that ranged from 117 patients (Austin and Convery 1993) to 920 patients (Fowler et al. 2000). Matzkin et al. (1993) did not report the source of data collection, but used 119 patients.

Furthermore, 18 of the 28 articles (64%) did not separate patients into two distinct age categories, but rather divided prostate cancer patients into three or greater age ranges (Table 1).

Thirteen of the 28 articles (46%) compared prostate cancer patients of all stages, as seen in Table 1. Four of the 28 articles included patients with specific cancer stages, and eleven articles did not report cancer staging (Table 1).

Survival and Morality Results

Survival and morality data were compared to determine the racial disparities between White and African American men across age. Nineteen of the 28 articles (68%) showed survival disparities decreased with age. Eight of the 28 articles (29%) showed similar disparities across age categories, and one article (3%) showed disparities increased with age.

Survival

Seven of 12 articles that measured survival data showed the survival gap between African American and White men decreased with age (Table 1). In Mebane et al. (1990), the sample size contained 7.4% of the total African American population and 5% of the White population, African Americans were found to have decreased survival compared to Whites in those less than 65, or 70–79 years of age, but Whites had similar or increased survival in the 65–69, or 80+ age groups. In a 2000 study by Fowler et al., which studied 920 patients total, the cause specific survival of African Americans less than age 70 with stage T1b-2 cancer were found to be lower than their White counterparts, but in the patients older than 70 years the survival was similar.

Furthermore, four of the 12 articles measuring survival demonstrated the disparity gap in survival did not change as patients aged (Table 1).

One article, Penson et al. (2007) found the disparity gap between African American men and Whites widened as the men increased in age. This article compared survival rates across age categories of 55–65, 55–65, 65–75, and 75 and older, and found a greater gap in survival in men aged 75 and older.

Mortality

Sixteen articles discussed mortality differences between African Americans and Whites across age categories (Table 1). Within these articles, 12 revealed the mortality gap between African American and White men decreased with age. Chu, Tarone, and Freeman (2003) measured mortality data of prostate cancer patients in the SEER program, which consisted of 10% of the United States population, and compared morality disparities between African American and White men at ages 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80–84, and 85 and older. The authors found a greater mortality gap in the 50–59 and 60–69 age groups, whereas in the 70–79, 80–89, and 85 and older age groups the mortality gap decreased. Brawley (2012) used graphical depictions of the data to depict a decrease in the mortality gap between African American and White men as age increased. Soto-Salgado et al. (2012) found a lower mortality rate in African Americans compared to non-Hispanic White men in those less than 75 years of age.

Four articles of the 16 articles that displayed disparities in mortality showed the mortality gap remained constant across increasing age categories (Table 1).

Discussion

Our systematic review focused on one aspect of racial disparities in prostate cancer patients – the age effect on survival and mortality differences between African American and White men. The majority of the articles (68%) indicated the gap in survival and mortality between African Americans and Whites lessened with increasing age. Our results agree with the most recent SEER review article, which shows a greater mortality difference between African American and White men younger than age 65 than of men older than age 65 (Howlader et al. 2014).

Within the articles, the differences in survival and mortality between blacks and whites in the “younger” and “older” age groups were compared. These age groups varied even across different articles, but the average division was determined to be age 65. Certain articles separate the patient population into age ranges of 5 or 10 years, and if so, these age ranges were taken into account and compared as a group of approximately before age 65 as “younger” and after age 65 as “older”.

This result may arise because: 1) among younger patients, African Americans may have more aggressive disease 2) among older patients, African American men may have greater competing causes of death, and 3) younger African Americans below age 65 and of lower socioeconomic status (SES) may have less financial access to appropriate health care treatment due to ineligibility for Medicare coverage.

The first explanation to the survival and mortality gap decreasing with age may be that among younger prostate cancer patients, more aggressive disease is seen in African American men than White men. Within the literature collected, several studies have found that in patients younger than 60–70 years, African Americans present with higher grade and/or higher staged tumors when compared to Whites, while in patients older than 60–70 years the difference is less pronounced (Austin 1990, 1993; Fowler et al. 2000). Powell et al. (1995) offered the explanation of earlier malignant transformation among African American men compared to Whites. Pienta et al. (1995) similarly concluded African Americans may either present with more aggressive disease at early ages, or less aggressive disease at later ages. Each study has noted that the aggressiveness in disease onset in younger years can contribute to decreasing disparities between African American and White men as age increases.

Furthermore, as prostate cancer patients age, African American patients may have increased competing causes of death, which may narrow the disparity gap between the races. However, Pienta et al. (1995) describes an alternative explanation that younger African American men may be dying of other comorbid events. Robbins et al. (2000) also postulates that the larger disparity in younger men may be because of increased risk in African American men for death from traumatic causes.

Another explanation for our study is that African American patients younger than age 65 have reduced access to medical care when compared to White patients. Ward et al. found the percent of African Americans under age 65 with no health insurance was almost twice that of Whites (Ward et al. 2004). African American prostate cancer patients were found more likely to be of low SES status (Schwartz et al. 2009), and Hoffman et al. (2001) found that insurance status and employment status were associated with the presentation of advanced disease of prostate cancer. Medicare could provide health care coverage to the patients over age 65 who could otherwise not afford adequate treatment, and create equal healthcare access to patients regardless of race. More African American men younger than age 65 may face lack of healthcare coverage due to ineligibility to Medicare. However, it should be noted socioeconomic factors are only a contributing factor to greater disparity in the younger patients. Hoffman et al. (2001) still concluded that SES factors alone could not explain the increased risk of advanced disease. Powell et al. found socioeconomic factors and financial access to care did not influence the differences in survival and mortality between African American and White patients, by finding African Americans patients with equal access to treatment at a Veterans Affairs medical center to still have poorer survival than Whites (1995). However, Powell et al. did not address whether socioeconomic factors could still be a contributing factor for racial disparities.

Therefore, biologic differences in disease progression, competing causes of death in older years, along with differences in access to care, may both contribute to the wider racial disparity gap in the younger patient population.

A potential limitation in the review would be the fact that several articles did not include complete reports of the sample size, data source, age ranges of the patients, and cancer staging of the patients, as listed in Table 1.

In addition, six articles (Fowler et al 2000; Powell, Schwartz and Hussain 1995; Brawley 2012; CDC 1992; Hsing and Devesa 1994; Piffath 2001) contained graphical presentation representing data trends across multiple years. These data points from the trends were manually extracted, which presented as a potential limitation to this article.

Moreover, the quality of articles also may be variable across studies. The study characteristics varied across the collected studies – namely the study design, sample size and geographic location of the articles. Therefore, all articles may not be of equal quality or relevant depending on the target population.

Finally, several articles compared prostate cancer disparity data across age along with other factors, such as different years of study and patient characteristics. The heterogeneity of the studies present as a limitation to the review. The articles collected had a wide range in publication dates – from 1977 to 2012. During this time, the detection and treatment of prostate cancer changed as literature and research was expanded. Brawley stated the prostate cancer mortality rate has declined by 39% from 1991 to 2008, and described the decrease as a result in improvements in screening and treatment, changes in the attribution of causes of death, and changes in hormonal therapy to prostate cancer patients.

Conclusion

The majority of the evidence from the literature in this systematic review measuring prostate cancer survival and mortality rates by race suggest a narrowing of the disparity gap with increasing age. This study focused solely on the disparities in survival and mortality between African American and White prostate cancer patients of different age groups, and further research should be conducted on both the biologic and socioeconomic factors contributing to racial disparities in prostate patients across age to further elucidate this disparity. This study opens dialogue on the fact that the racial disparity gap in prostate cancer patients lessens as they increase in age, and thus highlights the need to address the survival disparity gap among younger prostate cancer patients. Therefore, future studies and interventions should strive towards targeting the younger African American prostate cancer patient population, not only by studying the biologic differences between African Americans and Whites, but also by improving treatment access and receipt among younger African American men.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kim Yang for her guidance in conducting the systematic search for the review, and Laura Bogart for her assistance in reviewing the manuscript.

Funding: The work was supported by the National Institute on Aging Short-Term Training Program on Aging Grant (grant number T35AG036679).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Austin JP, Convery K. Age–race interaction in prostatic adenocarcinoma treated with external beam irradiation. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;16(2):140–145. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199304000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin Jean-Philippe, Aziz H, Potters L, Thelmo W, Chen P, Choi K, Brandys M, Macchia RJ, Rotman M. Diminished survival of young blacks with adenocarcinoma of the prostate. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1990;13(6):465–469. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199012000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawley OW. Trends in prostate cancer in the United States. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monograph. 2012;2012(45):152–156. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Trends in prostate cancer—United States, 1980–1988. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1992;41(23):401–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng I, Witte JS, McClure LA, Shema SJ, Cockburn MG, John EM, Clarke CA. Socioeconomic status and prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates among the diverse population of California. Cancer Causes & Control. 2009;20(8):1431–1440. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9369-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu KC, Tarone RE, Freeman HP. Trends in prostate cancer mortality among black men and white men in the United States. Cancer. 2003;97(6):1507–1516. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen ME, Chartrand M, Wetzel WF. A Markov model of the natural history of prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1994;47(1):3–21. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta GD, Glymour MM, Kosheleva A, Chen JT. Prostate cancer mortality and birth or adult residence in the southern United States. Cancer Causes & Control. 2012;23(7):1039–1046. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9970-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernster VL, Selvin S, Sacks ST, Austin DF, Brown SM, Winkelstein W. Prostatic cancer: mortality and incidence rates by race and social class. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1978;107(4):311–320. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernster VL, Winkelstein W, Jr, Selvin S, Brown SM, Sacks ST, Austin DF, Mandel SA, Bertolli TA. Race, socioeconomic status, and prostate cancer. Cancer Treatment Reports. 1977;61(2):187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JE, Bigler SA, Bowman G, Kilambi NK. Race and cause specific survival with prostate cancer: influence of clinical stage, Gleason score, age and treatment. Journal of Urology. 2000;163(1):137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)67989-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton JP. Progress in the control of prostate cancer, Rhode Island, 1987–1998. Medicine and health, Rhode Island. 2001;84(3):100–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel L, Mushinski M. Cancer incidence, mortality and survival: trends in four leading sites. Statistical Bulletin Metropolitan Insurance Company. 1994;75(3):19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman RM, Gilliland FD, Eley JW, Harlan LC, Stephenson RA, Stanford JL, Albertson PC, Hamilton AS, Hunt WC, Potosky AL. Racial and ethnic differences in advanced-stage prostate cancer: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2001;93(5):388–395. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.5.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2011. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2014. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/ [Google Scholar]

- Hsing AW, Devesa SS. Prostate cancer mortality in US by cohort year of birth, 1865–1940. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 1994;3(7):527–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kant AK, Glover C, Horm J, Schatzkin A, Harris TB. Does cancer survival differ for older patients? Cancer. 1992;70(11):2734–2740. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921201)70:11<2734::aid-cncr2820701127>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzkin H, Rangel MC, Soloway MS. Relapse on endocrine treatment in patients with stage D2 prostate cancer. Urology. 1993;41(2):144–148. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebane C, Gibbs T, Horm J. Current status of prostate cancer in North American black males. J Natl Med Assoc. 1990;82(11):782–788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill RM, Brawley OW. Prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates among white and black men. Epidemiology. 1997;8(2):126–131. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199703000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penson DF, Chan JM the Urologic Diseases in America Project. Prostate Cancer. Journal of Urology. 2007;177:2020–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienta KJ, Demers R, Hoff M, Kau TY, Montie JE, Severson RK. Effect of age and race on the survival of men with prostate cancer in the Metropolitan Detroit tricounty area, 1973 to 1987. Urology. 1995;45(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(95)96996-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piffath TA, Whiteman MK, Flaws JA, Fix AD, Bush TL. Ethnic differences in cancer mortality trends in the US, 1950–1992. Ethnicity & Health. 2001;6(2):105–19. doi: 10.1080/13557850120068432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell IJ, Banerjee M, Sakr W, Grignon D, Wood DP, Novallo M, Pontes E. Should African-American Men Be Tested for Prostate Carcinoma at an Earlier Age than White Men? Cancer. 1999;85(2):472–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell IJ, Schwartz K, Hussain M. Removal of the financial barrier to health care: does it impact on prostate cancer at presentation and survival? A comparative study between black and white men in a Veterans Affairs system. Urology. 1995;46(6):825–30. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell IJ, Bock CH, Ruterbusch JJ, Sakr W. Evidence supports a faster growth rate and/or earlier transformation to clinically significant prostate cancer in black than in white American men, and influences racial progression and mortality disparity. The Journal of Urology. 2010;183(5):1792–1797. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulte D, Redaniel MT, Brenner H, Jeffreys M. Changes in survival by ethnicity of patients with cancer between 1992–1996 and 2002–2006: is the discrepancy decreasing? Annals of Oncology. 2012;23:2428–34. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins AS, Whittemore AS, Thom DH. Differences in socioeconomic status and survival among white and black men with prostate cancer. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;151(4):409–16. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma AV, Schottenfeld D. Prostate cancer incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States: 1981–2001. Seminars in Urologic Oncology. 2002;20(1):3–9. doi: 10.1053/suro.2002.30390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz K, Powell IJ, Underwood W, George J, Yee C, Banerjee M. Interplay of Race, Socioeconomic Status and Treatment on Survival of Prostate Cancer Patients. Urology. 2009;74(6):1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Brown ML, Potosky AL, Klabunde CN, Davis WW, Moul JW, Fahey A. Race/ethnicity and the receipt of watchful waiting for the initial management of prostate cancer. Journal of general internal medicine. 2004;19(2):146–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Martin LB. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94(5):334–357. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.5.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Salgado M, Suárez E, Torres-Cintrón M, Pettaway CA, Colón V, Ortiz AP. Prostate cancer incidence and mortality among Puerto Ricans: an updated analysis comparing men in Puerto Rico with US racial/ethnic groups. Puerto Rico health sciences journal. 2012;31(3):107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taksler GB, Keatin NL, Cutler DM. Explaining racial differences in prostate cancer mortality. Cancer. 2012;118(17):4280–4289. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B, Figgs LW, Zahm SH. Differences in cancer incidence, mortality, and survival between African Americans and Whites. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1995;103(suppl 8):275–281. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s8275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace TA, Prueitt RL, Yi M, Howe TM, Gillespie JW, Yfantis HG, Stephens RM, Caporaso NE, Loffredo CA, Ambs S. Tumor immunobiological differences in prostate cancer between African-American and European-American men. Cancer Research. 2008;68(3):927–936. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, Singh GK, Cardinez C, Ghafoor A, Thun M. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2004;54(2):78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingo PA, Ries LA, Parker SL, Heath CW. Long-term cancer patient survival in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 1998;7(4):271–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.