Abstract

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is a widely used tool in critical care areas, allowing for the performance of accurate diagnoses and thus enhancing the decision-making process. Every major organ or system can be safely evaluated with POCUS. In that respect, the utility of POCUS in cardiac arrest is gaining interest. In this article, we will review the actual role of ultrasound in cardiac arrest and the main POCUS protocols focused to this scenario as well as discuss the potential role of POCUS in monitoring the efficacy of the chest compressions.

Keywords: Point-of-care, Ultrasound, Cardiac arrest, Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Sommario

La diagnostica ecografica (point-of-care ultrasound, POCUS) è uno strumento ampiamente utilizzato nelle aree di terapia intensiva e rianimazione, dove consente di ottenere diagnosi accurate e di migliorare il processo decisionale. Ogni grande organo o sistema puo’ essere tranquillamente esaminato con POCUS. In questo ambito, l’utilità del POCUS nei casi di arresto cardiaco sta riscuotendo un interesse crescente. In questo articolo passeremo in rassegna l’effettivo ruolo degli ultrasuoni nei casi di arresto cardico ed i principali protocolli POCUS mirati a questo scenario. Trattaremo inoltre il potenziale ruolo del POCUS nel monitoraggio dell’efficacia delle compressioni toraciche.

Introduction

Advanced life support is an essential component in the chain of survival for both in and out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (CA) [1, 2]. Several tools are employed in assessing the resuscitation process, aiming at optimizing the coronary and systemic blood flow and thus improving the likelihood of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) [1, 2]. In the overall CPR process, Point-of-care Ultrasound (POCUS) appears as a technique to be considered in the diagnosis of reversible causes of cardiac arrest, such as tamponade, pulmonary embolism, tension pneumothorax and hypovolemia [1, 2], as well as in distinguishing a true asystolia from a false asystolia. In this article, we will review the actual role of POCUS in cardiac arrest in diagnosing, monitoring and prognostication as well as discuss some other potential applications, such as in assessing the effectiveness of the chest compressions.

POCUS role in cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Diagnosis and monitoring

The current CPR guidelines recommend performing POCUS when a reversible cause of CA is suspected, although it is stated that the improvement of outcomes with the use of POCUS in CA has not been yet demonstrated [1, 2].

As previously mentioned, the main utility of POCUS in CA is suggested in non-shockable rhythms (i.e., pulseless electrical activity and asystolia), aiming at identifying reversible causes of CA, such as tamponade, pulmonary embolism, hypovolemia and tension pneumothorax [1, 2]. POCUS-guided pericardiocentesis thrombolytics, needle decompression and fluid challenges can be performed during CPR, many times resulting in ROSC [3, 4]. In this way, POCUS use in CPR can lead to improved management in a significative number of patients [3–5]. Additionally to rule in or out these four basic reversible causes of CA, other conditions can be diagnosed, such as severe valve problem, severe LV or RV systolic failure and cardiac rupture. However, the impact of POCUS in these arrests is uncertain.

Determining a true asystolia vs a fine ventricular fibrillation can be made using POCUS, especially when rhythm monitoring is in doubt (e.g., has artifacts), with both prognostic and therapeutic implications [6, 7], since patients with fine ventricular fibrillation probably benefit from defibrillation and have best chances of ROSC and survival.

Several POCUS protocols have been created to be used in the emergency and critically ill patient [8, 9], although few of them are focused on CRP for the recognition of reversible causes of CA, such as the CAUSE [10], FEEL [3], FEER [11], PEA [12] and SESAME protocols [13, 14] (Table 1). FEEL and FEER explore the heart only, CAUSE explores the heart and lung; PEA and SESAME are multi-organ protocols, exploring the heart, lung, abdomen and proximal deep veins of lower limbs (Table 1). Instead of arguing in favor of or against one protocol over the other, choosing one of them and using it systematically in the emergency department or critical care unit seems to be the best approach. Furthermore, each department can also create its own protocol or algorithm.

Table 1.

POCUS protocols to be used in CPR

| CAUSE10 | FEEL3

FEER11 |

SESAME13, 14 | PEA12 * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Lung ultrasound: pneumothorax | 2 | – | 1 | 1 |

| Proximal DVT (lower extremities) | – | – | 2–3 (first in non-traumatic arrest) | 3 |

| Abdomen: e.g., free fluid, ruptured abdominal aorta | – | – | 2–3 (first in traumatic arrest) | 3 |

Numbers refer to the order in which scans are performed

CAUSE cardiac arrest ultrasound exam, FEEL focused echocardiographic evaluation in life support, FEER focused echocardiographic evaluation in resuscitation, PEA parasternal-Epigastric-Abdomen and other scans (*the order of scans can vary according to clinical setting), SESAME sequential emergency scanning assessing mechanism or origin of shock of indistinct cause, DVT deep venous thrombosis

Integrating US into CPR should follow one basic premise: POCUS must not interfere with the CPR [15]. Thus, POCUS is safely integrated into the CPR when it is performed in the first rhythm assessment and in the 10 s intervals to check carotid pulse and observe other physiological variables (capnography, invasive arterial pressure) looking for signs of ROSC. Thus, operators should be properly trained in obtaining and interpreting images in these timeframes. The presence of an operator who is exclusively, or at least preferentially, dedicated to ultrasound scanning would be desirable. To authors’ knowledge, training recommendations regarding POCUS use in CA are not yet formulated. One can presume that using a multi-organ approach possesses a high learning curve in comparison with performing solely cardiac US or cardiac–lung US.

Technically, the US machine must have a very rapid boot-up and setup and be rapidly available [13, 14], as happens with portable equipment. Hand-held devices are also useful for this purpose. Using a single transducer capable of exploring all areas (e.g., a convex or microconvex probe) is preferable or eventually two transducers, such as a phased-array probe and a linear probe, as long as rapid switch between them is achievable.

An algorithm for using POCUS in CA is proposed in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. It is intuitively desirable to use a rational “holistic” approach, always starting with cardiac images (subcostal four-chamber and inferior vena cava views, if not enough, parasternal long axis or apical four-chamber view) and then exploring the next area (if required) based on cardiac images (and clinical correlation, if possible). For example, a clear tamponade does not require another exploration while an enlarged right ventricle (RV) raising suspicion of lung embolism usually mandates an exploration for deep vein thrombosis (in the first minutes of CPR, since thereafter ventricular equalization occurs and RV dilation is not categorical for lung embolism). Acute RV dilation occurs after a few minutes of arrest as blood is translocated from the systemic circulation to the right side of the heart along its pressure gradient. This means that right ventricle strain and pulmonary embolism should be cautiously ruled in on late cardiac arrest [16, 17]. Fortunately, deep vein thrombosis assessment is made without interrupting chest compressions. In addition, evaluating the pleura and abdomen in search of effusions (hemorrhages, in particular) or a ruptured abdominal aorta do not interfere with the CPR.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for the integration of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). VT ventricular tachycardia, VF ventricular fibrillation, ROSC return of spontaneous circulation, EKG electrocardiogram, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, PEA pulseless electrical activity, EMD electromechanical dissociation. Extracorporeal CPR (eCPR) should be considered to facilitate coronary angiography and PCI in coronary thrombosis

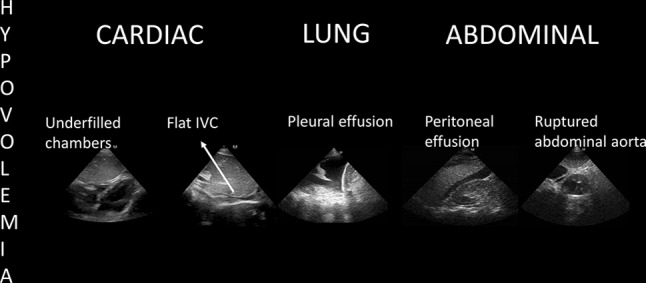

Fig. 2.

POCUS findings of hypovolemia in cardiac arrest. Once echocardiography shows depleted chambers and a flat inferior vena cava (IVC), a source of fluids loss must be followed in pleural and abdominal cavities while fluid challenges are administered during ongoing CPR. Other therapies should be employed if available, for example, REBOA resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in sub diaphragmatic sources of bleeding

Fig. 3.

POCUS findings of hypertensive pneumothorax in cardiac arrest. Once this diagnosis is made, needle thoracocentesis should be performed during ongoing CPR

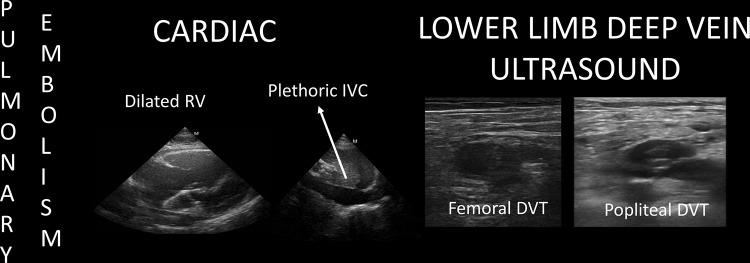

Fig. 4.

POCUS findings of pulmonary embolism in cardiac arrest. Once echocardiography shows a dilated RV and a plethoric IVC, a lower limb deep vein scanning is performed searching for a DVT (deep vein thrombosis). Thrombolytics are administered during ongoing CPR. Extracorporeal CPR (eCPR) should be considered to facilitate pulmonary thrombectomy

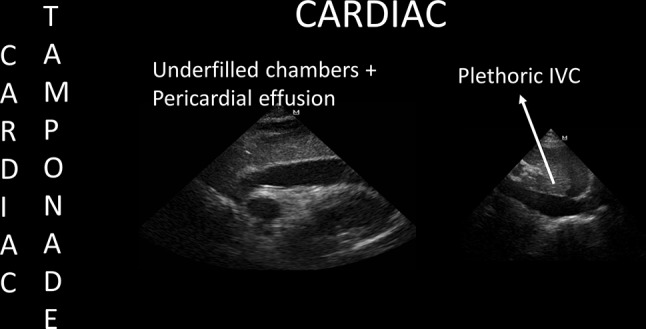

Fig. 5.

POCUS findings of cardiac tamponade in cardiac arrest. Once echocardiography shows these categorical findings, fluid challenges and ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis are performed during ongoing CPR

Fig. 6.

POCUS findings in cardiac arrest not related to hypovolemia, hypertensive pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade or pulmonary embolism. Treatments can be guided based on some findings, for example, fluid challenges in RV infarction (and patient transferred for PCI). Extracorporeal CPR (eCPR) should be considered to facilitate coronary angiography and PCI in coronary thrombosis

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is useful to assess patients in CA with inadequate or insufficient TTE windows. Its main advantage over TTE is that it can be used continuously without interrupting chest compressions [18]. Disadvantages are the lack of observation of direct causes of CA, such as abdominal bleeding or pneumothorax. Main limitations for its use are availability and costs.

Prognosis

Determining a true asystolia (absence of cardiac contraction or cardiac standstill) vs a still-contracting heart, is another interesting data provided by POCUS. When using POCUS, studies has shown that 10–35% of asystolic patients have demonstrable cardiac contraction [3, 4]. Cardiac contraction can be defined as any visible movement of the myocardium, excluding movement of blood within the cardiac chambers or isolated valve movement [4]. Demonstration of cardiac contraction on initial US is of paramount prognostic importance. In a recent multicenter study involving 793 out-of-hospital CA and in-ED CA patients with pulseless electrical activity (PEA) or asystolia, cardiac activity was present in 33% of the patients on initial US and was associated with ROSC (OR 2.8, 1.9–4.2), survival to hospital admission (OR 3.6, 2.2–5.9), and survival to hospital discharge (OR 5.7, 1.5–21.9); whereas patients who lacked detectable cardiac activity had poor ROSC and overall survival rate. Overall, ROSC rate was over 50% if cardiac activity was detected vs. 14.1% if none was documented [4]. It should be noted that ROSC detection depends on the presence of a pulse, capnography and invasive arterial pressure readings; therefore, it is not equivalent in an isolated manner on the presence of cardiac contractility on POCUS.

A meta-analysis of eight studies (n = 568) with mixed non-traumatic and traumatic arrest patients [19] also showed a poor likelihood of ROSC and survival when no cardiac activity was detected, but a modest increase in ROSC and survival (LR 5) if cardiac contraction was present. Other studies showed similar results [5, 20].

While a ROSC and overall survival rate are poor when no cardiac contraction was observed, this cannot be applied as a strict standard criteria to not initiate or cease the resuscitation efforts, since there is still a low number of patients who can achieve ROSC and survival [4, 19], especially those with witnessed arrests, early CPR, short down time [19] or a potentially reversible cause of CA.

Potential application of POCUS in CPR

Efficacy of the compressions is of paramount interest in CPR, since proper compressions are associated with ROSC and survival. To date, capnography and invasive arterial pressure are the two main tools recommended in the CPR guidelines to monitor resuscitation maneuvers in advanced CPR [1, 2]. A potential utility of POCUS is in the direct evaluation of the compressions, providing real-time observation of the squeezing and relaxation of the cardiac chambers under compressions. Several studies have demonstrated that the area of maximal compression when providing chest compressions many times result in no blood pumping in a significative percentage of patients, since it is mainly compressed the ascending aorta, aortic root or the left ventricle outflow tract, but not the left ventricle [21, 22]; thus POCUS may aid in adjusting the applied forces and hands location for optimization of the compressions. Transthoracic echocardiography for this purpose has several drawbacks, such as the movement of the transducer with chest compressions and the interference between hands of providers and the positioning of the transducer. Transesophageal echocardiography does not have the limitations of TTE regarding the movement and positioning of the transducer and thus has a potential role in advanced CPR in assessing the efficacy of the compressions [18]. In fact, mechanisms of flow during CPR (cardiac pump theory vs thoracic pump theory) were best investigated with TEE in several studies [23–25]. However, both TTE and TEE show standardization issues, since they are not clear as to what variables operators should assess to determine whether compressions are optimal or not.

Conclusions

POCUS in CPR is helpful in diagnosing reversible causes of cardiac arrest; in distinguishing a true from a false asystolia as well as in monitoring the overall CPR process; including using POCUS for guiding interventions (e.g., POCUS guided pericardiocentesis). Prognostic information (likely of ROSC and survival) is also provided by POCUS when this is performed on the first rhythm assessment as well as in hand-off periods. Finally, efficacy of the chest compressions is an interesting issue that can be evaluated with POCUS, especially TEE, however, further studies are needed to provide firm recommendations in that issue.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Human and animal studies

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Contributor Information

Pablo Blanco, Phone: +5402262521943, Email: ohtusabes@gmail.com.

Carmen Martínez Buendía, Phone: +34649635587, Email: cmbuendia@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Soar J, Nolan JP, Böttiger BW, Perkins GD, Lott C, Carli P, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 3. Adult Advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2015;95:100–147. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Link MS, Berkow LC, Kudenchuk PJ, Halperin HR, Hess EP, Moitra VK, et al. Part 7: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2015 American heart association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015;132(18 Suppl 2):S444–S464. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breitkreutz R, Price S, Steiger HV, Seeger FH, Ilper H, Ackermann H, et al. Focused echocardiographic evaluation in life support and peri-resuscitation of emergency patients: a prospective trial. Resuscitation. 2010;81(11):1527–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaspari R, Weekes A, Adhikari S, Noble VE, Nomura JT, Theodoro D, et al. Emergency department point-of-care ultrasound in out-of-hospital and in-ED cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016;109:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chardoli M, Heidari F, Rabiee H, Sharif-Alhoseini M, Shokoohi H, Rahimi-Movaghar V. Echocardiography integrated ACLS protocol versus conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients with pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest. Chin J Traumatol. 2012;15(5):284–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amaya SC, Langsam A. Ultrasound detection of ventricular fibrillation disguised as asystole. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(3):344–346. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Querellou E, Meyran D, Petitjean F, Le Dreff P, Maurin O. Ventricular fibrillation diagnosed with trans-thoracic echocardiography. Resuscitation. 2009;80(10):1211–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seif D, Perera P, Mailhot T, Riley D, Mandavia D. Bedside ultrasound in resuscitation and the rapid ultrasound in shock protocol. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:503254. doi: 10.1155/2012/503254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco P, Miralles Aguiar F, Blaivas M. Rapid ultrasound in shock (RUSH) velocity-time integral: a proposal to expand the RUSH protocol. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:1691–1700. doi: 10.7863/ultra.15.14.08059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez C, Shuler K, Hannan H, Sonyika C, Likourezos A, Marshall J. C.A.U.S.E.: cardiac arrest ultra-sound exam—a better approach to managing patients in primary non-arrhythmogenic cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2008;76(2):198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breitkreutz R, Walcher F, Seeger FH. Focused echocardiographic evaluation in resuscitation management: concept of an advanced life support-conformed algorithm. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(5 Suppl):S150–S161. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260626.23848.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Testa A, Cibinel GA, Portale G, Forte P, Giannuzzi R, Pignataro G, Silveri NG. The proposal of an integrated ultrasonographic approach into the ALS algorithm for cardiac arrest: the PEA protocol. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14(2):77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lichtenstein D. How can the use of lung ultrasound in cardiac arrest make ultrasound a holistic discipline? The example of the SESAME-protocol. Med Ultrason. 2014;16(3):252–255. doi: 10.11152/mu.2013.2066.163.dal1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lichtenstein D, Malbrain ML. Critical care ultrasound in cardiac arrest. Technological requirements for performing the SESAME-protocol—a holistic approach. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2015;47(5):471–481. doi: 10.5603/AIT.a2015.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labovitz AJ, Noble VE, Bierig M, Goldstein SA, Jones R, Kort S, et al. Focused cardiac ultrasound in the emergent setting: a consensus statement of the American Society of Echocardiography and American College of Emergency Physicians. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(12):1225–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Querellou E, Leyral J, Brun C, Lévy D, Bessereau J, Meyran D, Le Dreff P. In and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and echography: a review. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2009;28(9):769–778. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanco P, Volpicelli G. Common pitfalls in point-of-care ultrasound: a practical guide for emergency and critical care physicians. Crit Ultrasound J. 2016;8(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s13089-016-0052-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blaivas M. Transesophageal echocardiography during cardiopulmonary arrest in the emergency department. Resuscitation. 2008;78(2):135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blyth L, Atkinson P, Gadd K, Lang E. Bedside focused echocardiography as predictor of survival in cardiac arrest patients: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(10):1119–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flato UA, Paiva EF, Carballo MT, Buehler AM, Marco R, Timerman A. Echocardiography for prognostication during the resuscitation of intensive care unit patients with non-shockable rhythm cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2015;92:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang SO, Zhao PG, Choi HJ, Park KH, Cha KC, Park SM, Kim SC, Kim H, Lee KH. Compression of the left ventricular outflow tract during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(10):928–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin J, Rhee JE, Kim K. Is the inter-nipple line the correct hand position for effective chest compression in adult cardiopulmonary resuscitation? Resuscitation. 2007;75(2):305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higano ST, Oh JK, Ewy GA, Seward JB. The mechanism of blood flow during closed chest cardiac massage in humans: transesophageal echocardiographic observations. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65(11):1432–1440. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)62167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kühn C, Juchems R, Frese W. Evidence for the ‘cardiac pump theory’ in cardiopulmonary resuscitation in man by transesophageal echocardiography. Resuscitation. 1991;22(3):275–282. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(91)90035-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu P, Gao Y, Fu X, Lu J, Zhou Y, Wei X, et al. Pump models assessed by transesophageal echocardiography during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Chin Med J (Engl) 2002;115(3):359–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]