Abstract

Purpose

Different shear wave elastography (SWE) machines able to quantify liver stiffness (LS) have been recently introduced by various companies. The aim of this study was to investigate the agreement between point SWE with Esaote MyLab Twice (pSWE.ESA) and 2D SWE with Aixplorer SuperSonic (2D SWE.SSI). Moreover, we assessed the correlation of these machines with Fibroscan in a subgroup of patients.

Methods

A total of 81 liver disease patients and 27 subjects without liver disease accessing the ultrasound lab were considered. Exclusion criteria were liver nodules, BMI >35, and severe comorbidities. LS was sampled from the same intercostal space with both pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI and values were tested with Lin’s analysis and Bland–Altman analysis (B&A). Agreement between each SWE machine and Fibroscan was assessed in 26 liver disease patients with Spearman correlation.

Results

Precision and accuracy between pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI were, respectively, 0.839 and 0.999. B&A showed a mean of only −0.2 kPa, with no systematic deviation between the techniques and limits of agreement at −11.6 and 11.3 kPa. Spearman’s rho correlation versus Fibroscan was 0.849 for pSWE.ESA and 0.878 for 2D SWE.SSI. The relationship became less strict in the higher range of LS (≥15.2 kPa), corresponding to cirrhosis.

Conclusion

The overall degree of concordance of pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI in measuring LS resulted remarkable, also when compared with Fibroscan. The less strict correlation for patients with LS in the higher range would not affect the staging of disease as such patients are anyhow classified as cirrhotic.

Keywords: Shear wave elastography, Ultrasound, Fibroscan, Liver stiffness, Liver fibrosis, Portal hypertension

Astratto

Obiettivo

Differenti metodiche di shear wave elastography (SWE) in grado di misurare la rigidità epatica (RE) sono state recentemente implementate su vari ecografi. Questo studio vuole valutare la concordanza fra Esaote MyLab Twice point SWE (pSWE.ESA) e Aixplorer SuperSonic 2DSWE (2DSWE.SSI). Inoltre si è potuto anche valutare la correlazione fra queste macchine e il Fibroscan in un sottogruppo di pazienti.

Metodi

Sono stati arruolati 81 pazienti con epatopatia cronica e 27 soggetti con fegato sano afferenti al laboratorio di ecografia. Sono stati esclusi pazienti con lesioni focali epatiche, BMI >35 kg/m2, severe comorbidità. La RE è stata misurata dallo stesso spazio intercostale sia con pSWE.ESA che 2D SWE.SSI e i valori sono stati confrontati con analisi di Lin ed analisi di Bland–Altman (B&A). La concordanza fra ciascuna metodica SWE e il Fibroscan è stata valutata in 26 pazienti epatopatici tramite correlazione di Spearman.

Risultati

Precisione ed accuratezza sono risultate rispettivamente 0.839 e 0.999. L’analisi di B&A ha mostrato uno scarto medio di soli −0.2 kPa e limiti di concordanza a −11.6 e 11.3 kPa, senza rilevare alcuna deviazione sistematica fra le due macchine. Il coefficiente di correlazione con il Fibroscan è risultato 0.849 per pSWE.ESA e 0.878 per 2D SWE.SSI. Si è osservata una lieve deflessione del coefficiente di concordanza tra le due metodiche per alti valori di RE (all’interno della classe corrispondente alla cirrosi).

Conclusione

La concordanza fra pSWE.ESA e 2DSWE.SSI è risultata globalmente elevata, anche nel confronto con il Fibroscan. La stadiazione dell’epatopatia non viene compromessa dal calo di correlazione ai valori più alti di RE, in quanto tali pazienti verrebbero comunque classificati come cirrotici.

Introduction

Prognosis and management of patients with liver disease are basically guided by fibrosis status and portal hypertension [1–3]. The arrival of transient elastography (TE) in 2003 represented a milestone in hepatology, giving the possibility to clinicians to non-invasively evaluate these features through the measurement of liver stiffness (LS) [4–6]. Since 2008, this quantification becomes possible with shear wave elastography (SWE) implemented in ultrasound (US) systems [7]. Different technologies introduced on the market have been later on classified by EFSUMB [8, 9].

The potential shown by SWE in the clinical scenario has driven most companies to embed their devices with new proprietary technologies for LS measurement. However, due to this rapid and very recent outbreak, clinical evidences about many of them are missing [10]. Esaote point SWE (pSWE.ESA) on MyLab Twice belongs to this group, since it was released only in 2016 and very few data have been published in full to date to the best of our knowledge [11].

Validation of a new technology for liver assessment should be at best tested versus liver histology as reference. However in recent years, the number of biopsies for chronic liver disease dramatically dropped, especially after the introduction of new direct acting antivirals for hepatitis C, an etiology accounting for about 50% of chronic liver disease in Italy. With no more need for liver biopsy in hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients, its use has shifted in current clinical practice to the unsolved atypical cases, which would no more be the perfectly suited reference standard for LS studies.

Given the above illustrated impossibility to perform a study with histology as reference standard in consecutive cases series of patients with liver disease for ethical and practical reasons, we decided to compare pSWE.ESA with Supersonic Imagine Aixplorer 2D SWE (2D SWE.SSI) held as reference, since this technique has already shown optimum performances in several etiologies of liver disease, very close to that of Fibroscan [11–16]. Moreover, data about 2D SWE.SSI with histology as reference standard have been recently published in the form of a large metanalysis based on individual (>1000) cases, which showed not only that the diagnostic accuracy of 2D SWE.SSI was very good, but on average slightly better than Fibroscan for all individual liver disease etiologies [17].

The main aim of the study was, therefore, to assess the degree of concordance between pSWE.ESA and real-time 2D SWE.SSI in measuring LS. Furthermore, we aimed at assessing the correlations of such technologies with the most extensively utilized non invasive reference standard, namely transient elastography, in a subgroup of patients.

The secondary aim was to verify whether the choice of the intercostal space made by the operator is a relevant factor in determining LS values, considering the sampling variability of liver fibrosis [18].

Patients and methods

Patients

In this cross-sectional study, we screened patients with liver disease of any stage, regardless of etiology, referred to our US lab for abdominal ultrasound. Diagnosis of liver disease and cirrhosis was made by clinical, laboratory, imaging, elastography and, if mandatory, histology findings. Patients with severe extrahepatic comorbidities, particularly cardiac and respiratory, focal liver lesions, Body Mass Index (BMI) >35 and age <18, higly elevated liver stiffness (over 5 times the upper limit of normality), were excluded. The measurement of LS with the two machines was offered to the suitable patients. A total of 86 patients were enrolled in this study.

Subjects accessing the US lab for a screening exam with no clinical nor laboratory signs of liver disease were enrolled as a healthy liver group. They were either inpatients or outpatients with no apparent severe disease (e.g. low urinary tract infections, screening for thyroid nodules, neck lymph nodes, pancreatic focal lesions, carotid and vertebral Doppler ultrasound, familiar history of malignancies, healthy volunteers submitted to a screening exam, etc.). pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI were successful in all of them. The protocol was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki (and its later amendments); informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Since failure (as defined below) of pSWE.ESA to provide LS results occurred in 5 liver disease patients, in one of which also 2D SWE.SSI failed, the final total study population with LS data was made of 108 subjects (81 liver disease patients and 27 subjects with healthy liver).

Subjects were examined fasting from at least 6 h, lying in supine position with the right arm in maximal abduction and breath hold at tidal volume during each measurement. Two operators took part into the study, with, respectively, 1 and more than 20 years of experience in performing US; each operator was expert for both machines with more than 200 exams already performed, having completed the learning curve. Each operator consecutively performed LS assessment with pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI through the same intercostal space setting the sampling region at no less than 10 mm of distance from the Glisson capsule and not deeper than 70 mm from the probe. pSWE.ESA line and 2D SWE.SSI region of interest (ROI) were positioned as much as possible in the middle sector of scanned area (i.e. when free from large vessels). Operators attempted to minimize any possible patient-related source of variability between the both machines keeping the patient in the same position and aiming at the same level of breath hold at tidal volume, guided by B-mode visualization.

Intercostal spaces, freely chosen by the operator, were non-invasively marked with a temporary skin pencil before performing the first measurement to make sure to reproduce the experiment in the correct space, as described elsewhere [11]. To verify whether the choice of the intercostal space influences LS values, measurements were taken from two different spaces (named S1 and S2) with both pSWE.ESA (36 cases) and 2D SWE.SSI (45 cases) in two subsets of subjects.

Point shear wave elastography

pSWE.ESA examination was performed with a MyLab Twice equipment (Esaote, Genova, Italy) with convex probe CA451. This system induces microscopic tissue displacements by delivering an US pushing beam through the probe. The displacement generates a shear wave that moves laterally at a speed depending on the viscoelastic properties of the tissue and which attenuates laterally within 5–10 mm. As the wave speed is captured in a small ROI of few millimeters, it is categorized as point SWE (pSWE) [19]. The quantitative value of stiffness is obtained converting speed measured in meters/seconds in kilopascals (kPa) using the Young’s Modulus [8, 20]. A minimum of 5 LS acquisitions were expected, but with a maximum of 20 measurement attempts. Technical success rate (SR) was defined as the ratio of valid measurements out of total attempts. Attempts failed when the elastography software gave no value in response to the elastography impulse (thus, measurements could only be either valid or invalid). Median values in kPa and interquartile range (IQR) of a single set, directly provided by the software, were considered for the analysis.

2D shear wave elastography

Real-time 2D SWE.SSI was performed with Aixplorer (SuperSonic Imagine, Aix-en-Provence, France) with convex probe XC6-1. This technique generates a Mach cone-shaped shear wave arising from the longitudinal axis captured with an ultrafast detection system [19]. The system gives the output in real-time intervals of approximately one second as a colour map averaging tissue stiffness of the sampled region during the acquisition time [8, 21]. The best area for stiffness quantification within the stiffness trapezoidal box of 2.5 by 3.5 cm is defined by an adjustable circular ROI that can be moved freely by the operator within the box map, with the B-mode image frozen in background. Operators were left free to choose position and diameter of the ROI (provided it was no less than 10 mm) obtaining a minimum of 5 measurements with up to 20 attempts. Measurements were considered failed when the box showed no color map (artifacts excluded) after a satisfactory time of around 15 s or when it was not possible to find a sufficiently large ROI (at least 6 mm in diameter) of homogeneous signals due to artifacts or lack of stiffness signals. The occurrence of failure was left to the judgement of expert operators. Then mean values and standard deviation (SD) of stiffness in kPa inside the ROI are computed by the system. Median values of a single set were considered for the analysis.

Transient elastography

Transient elastography with Fibroscan was not included in the specific protocol as the equipment was not readily available in the same room of the other two machines. However, some of the 81 patients with liver disease had also been submitted to transient elastography with Fibroscan with an M-probe performed according to the standard metholodogy by expert operators [11, 22]. In 26 patients, such exam was performed within one month from the study investigations with no intervening etiological treatment of liver disease in the meantime (e.g. antivirals, alcohol withdrawal) and produced valid measurements (IQR/median ratio <0.3 and SR >60%). Thus, we compared the data of pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI with Fibroscan in this subgroup of patients.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with MedCalc (v.14.8.1, MedCalc Software bvba, Mariakerke, Belgium). Normality of the distribution of the findings was assessed with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics were performed for demographic, anthropometric, clinical, laboratory parameters and for IQR/median ratio of LS measurements. Median values are reported if distribution did not result normal, otherwise the mean is shown. BMI data were compared with T test. Qualitative data are expressed as fractions and percentages.

The agreement between the equipments was assessed with Lin’s correlation concordance coefficient (CCC) and Bland–Altman analysis (B&A) [23, 24]. CCC is obtained from the product of precision (Pearson coefficient, determined by the scattering of values on the plot) and accuracy (graphically represented by the deviation of regression line from the reference 45° line). Each parameter is a number ranging from 0 (gross differences between the measures) to 1 (perfect agreement). Scatter plots are shown with local regression smoothing trend line (66% smoothing span) and the results of Pearson analysis in legend.

B&A analysis tests the relationship of the difference between two variables plotted against their mean, showing mean value of the difference and limits of agreement (LoA) of two series of data. We performed B&A with percentage values on the y axis to reduce the bias due to the natural increase of a difference as magnitude of minuend and subtrahend increases. Results of B&A with absolute differences are shown only in tables.

Comparison between SRs were made with Chi-square test.

Firstly, we tested the overall agreement between pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI in all the 108 subjects enrolled, recording also SR of both machines and IQR/median ratio of pSWE.ESA for each measurement as well as demographic and anthropometric data of the patients. Furthermore, a specific analysis was carried out including only the 81 patients with liver disease, as they are the principal target population of SWE.

Then, agreement analysis was performed splitting groups according to LS values measured with 2D SWE.SSI in order to test the performance in patients with or without expected cirrhosis to point out the relationships in the two clinically different situations (with or without cirrhosis). We decided to use a cutoff value of 15.2 kPa, slightly higher that usual value in the literature for F4 patients, in order to include patients with expected clearly established cirrhosis regardless of the etiology. Thus, pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI LS values were compared separately in subjects with LS <15.2 kPa (80 cases) and LS ≥15.2 kPa (28 cases).

The pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI findings of the 26 patients with liver disease and LS values obtained with Fibroscan were analyzed with Spearman rank correlation, since distribution of values resulted not normal. Results are displayed in scatter plots with regression line.

Results

Study population

Descriptive statistics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Data from laboratory exams no older than 2 months available at the moment of the study are reported in Table 2. All the subjects included in subgroup with 2D SWE.SSI values ≥15.2 kPa were found affected by established cirrhosis diagnosed on clinical and/or imaging data, whereas only 9 out of 80 (11.3%) subjects suffered this condition among those with values <15.2 kPa.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study population

| Study population | N (108) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Males | 72 | 66.7 |

| Females | 36 | 33.3 |

| Liver disease patients | 81 | 75.0 |

| Healthy liver subjects | 27 | 25.0 |

| Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58 | 22–86 |

| Liver disease patients | N (81) | % |

|---|---|---|

| HCV | 43 | 53.1 |

| NAFL | 12 | 14.8 |

| NASH | 7 | 8.7 |

| HBV | 6 | 7.4 |

| ASH | 5 | 6.2 |

| AIH | 2 | 2.5 |

| HBV-delta | 1 | 1.2 |

| NUVT | 1 | 1.2 |

| PSC | 1 | 1.2 |

| PVT | 1 | 1.2 |

| Cryptogenic | 2 | 2.5 |

HCV hepatitis C virus, NAFL non-alcoholic fatty liver, NASH non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, HBV hepatitis B virus, ASH alcoholic steatohepatitis, AIH autoimmune hepatitis, NUVT neonatal umbilical vein thrombosis, PSC primary sclerosing cholangitis, PVT portal vein thrombosis

Table 2.

Laboratory data of 81 liver disease patients enrolled in the study

| Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 | 2.6–4.8 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.82 | 0.3–4.40 |

| PT (INR) | 1.07 | 0.89–1.96 |

| AST (U/L) | 30 | 12–113 |

| ALT (U/L) | 28 | 10–89 |

| ALP (U/L) | 82 | 32–321 |

| GGT (U/L) | 40 | 12–354 |

| PLTs (units/mm3) | 186 | 38–331 |

PT prothrombin time, INR international normalized ratio, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, GGT gamma-glutamyl transferase, PLTs platelets

Mean BMI was 24.3 kg/m2 (SD = 3.0) with overweight status characterizing 44 out of 81 (54.3%) subjects [25]. Ascites, from minimal to moderate, was present in 6 out of 81 (7.4%) patients.

pSWE.ESA performances compared to 2D SWE.SSI

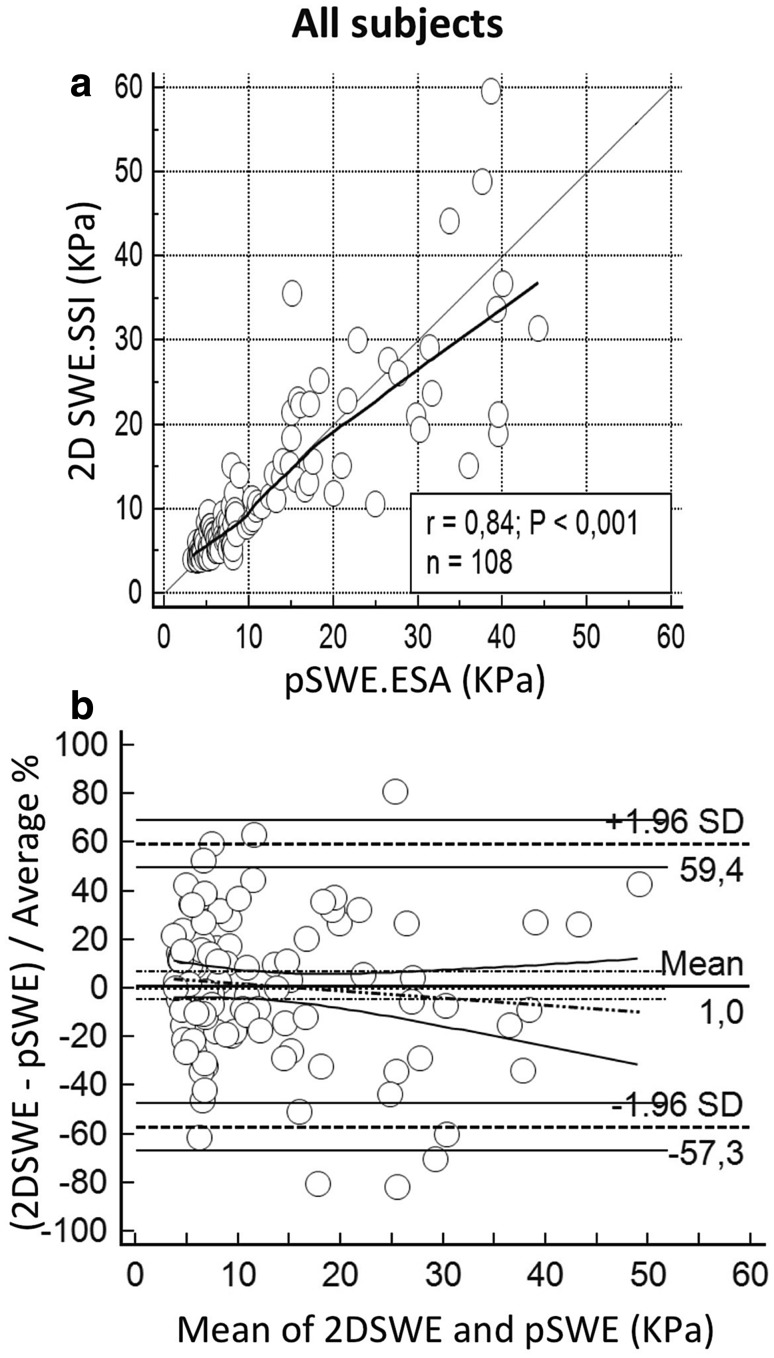

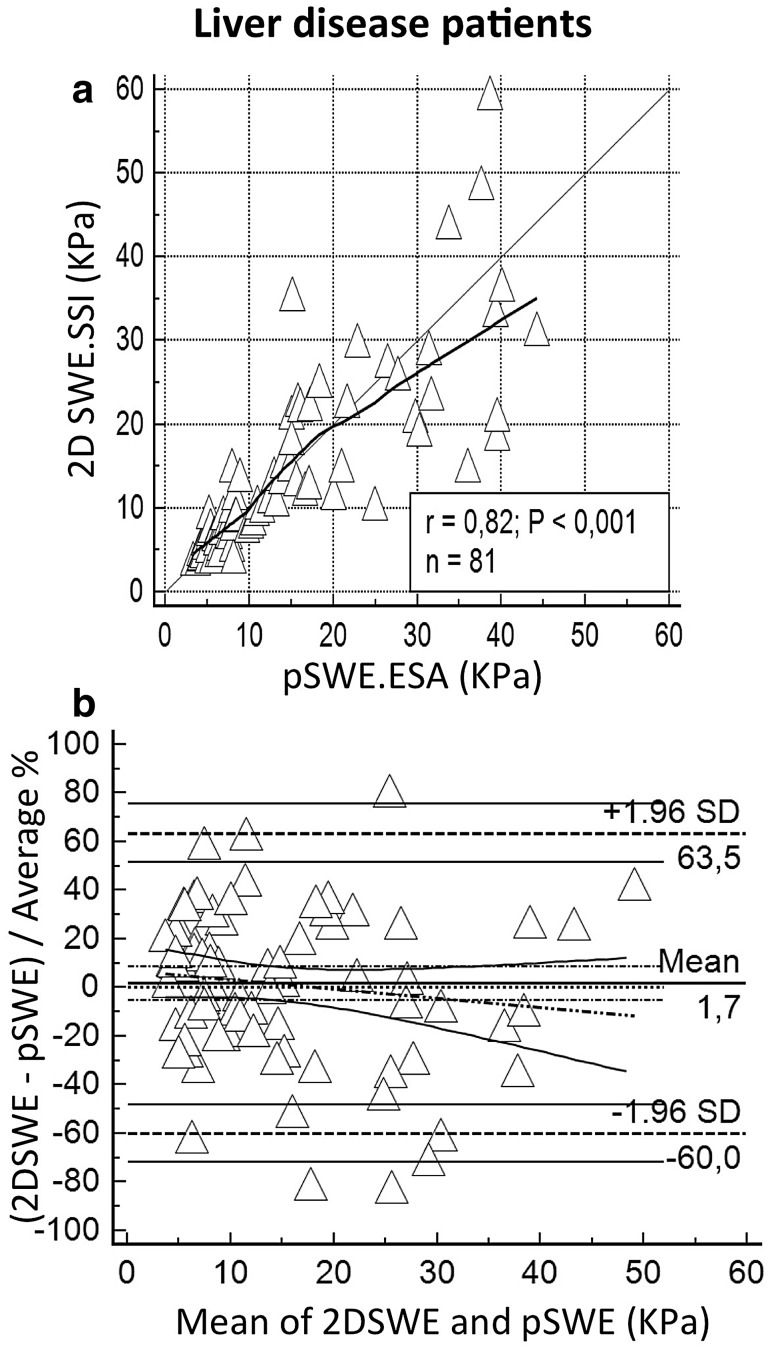

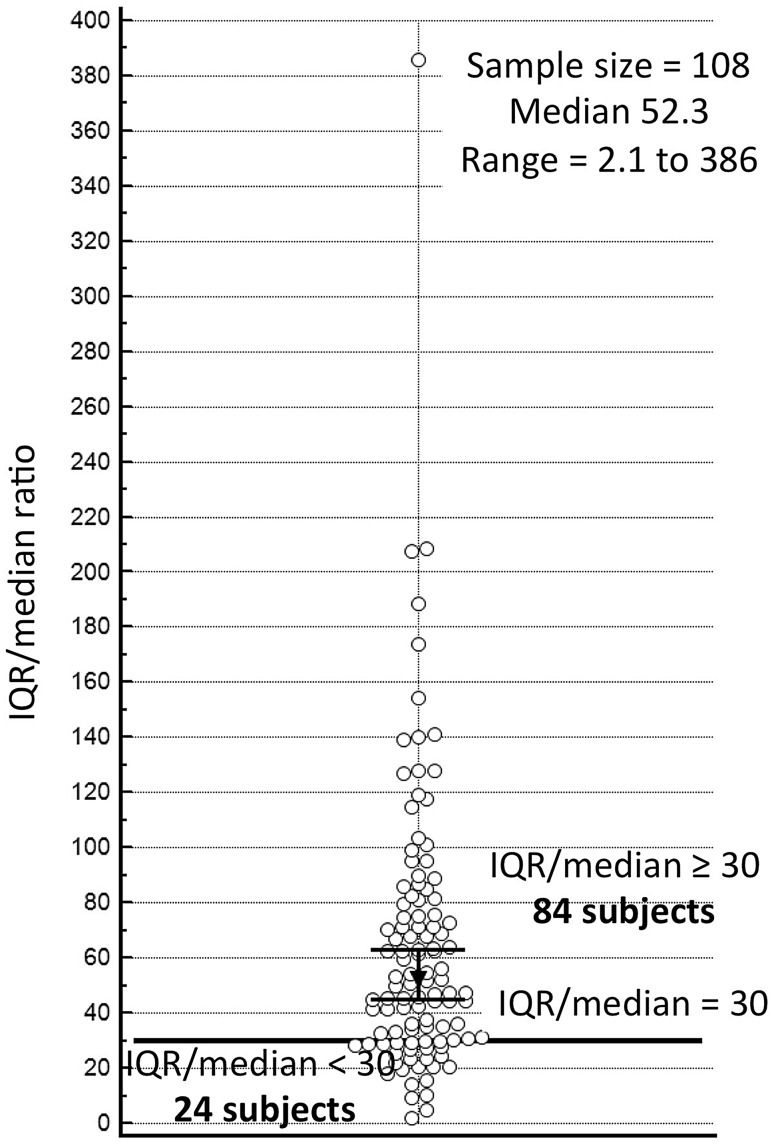

The correlation between pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI was very good when all subjects (n = 108) were assessed. Precision and accuracy were, respectively, 0.839 and 0.999. Similar performances emerged also in the 81 liver disease patients, with precision of 0.818 and accuracy of 0.999. Extended findings for these groups are reported in Table 3, Figs. 1 and 2. Figure 3 represents the distribution of IQR/median values of pSWE.ESA measurements.

Table 3.

Main results of the study

| Overall 2D SWE.SSI vs pSWE.ESA | ||

|---|---|---|

| All subjects (n = 108) | Liver disease patients (n = 81) | |

| 2D SWE.SSI median LS (kPa) | 8.4* | 10.4> |

| Range | 3.9–59.6 | 4.0–59.6 |

| pSWE.ESA median LS (kPa) | 8.0* | 10.2> |

| Range | 3.3–44.2 | 3.3–44.2 |

| Lin’s analysis | ||

| CCC (95% CI) | 0.838 (0.772 to 0.887) | 0.819 (0.730 to 0.879) |

| Precision | 0.839 | 0.818 |

| Accuracy | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Bland–Altman | ||

| Mean (95% CI) (kPa) | −0.2 (−1.3 to 1.0) | −0.2 (−1.7 to 1.3) |

| LoA (kPa) | −11.6 to 11.3 | −13.29 to 12.95 |

| T test (H0: mean = 0) | p = 0.786 | p = 0.820 |

| Bland–Altman % | ||

| Mean (95% CI) (kPa) | 1.0 (−4.6 to 6.7) % | 1.7 (−5.2 to 8.7) % |

| LoA (kPa) | −57.3 to 59.4% | −60.0 to 63.5% |

| T test (H0: mean = 0) | p = 0.716 | p = 0.620 |

Results of Pearson analysis, Lin’s analysis and Bland–Altman analysis are reported in the table including all 108 subjects enrolled and 81 liver disease patients

* p = 0.816; > p = 0.739

Fig. 1.

Overall comparison between liver stiffness measured with 2D SWE.SSI and pSWE.ESA. a Scatter plot with LOESS line (thick) and reference line (y = x, thin). b Bland–Altman plots with mean difference (thick horizontal line) and LoA (dashed horizontal lines) with the respective Confidence Intervals (continuous lines); regression line (dashes and points) is shown with Confidence Intervals lines (continuous)

Fig. 2.

Comparison between LS measured with 2D SWE.SSI and pSWE.ESA including only patients with liver disease. a Scatter plot with LOESS line (thick) and reference line (y = x, thin). Legend reports Pearson coefficient (r), p value of Pearson analysis (P) and sample size (n). b B&A plots with mean difference (thick horizontal line) and LoA (dashed horizontal lines) with the respective CIs (continuous lines); regression line (dashes and points) is shown with CI lines (continuous)

Fig. 3.

Dot plot showing distribution of pSWE IQR/median ratio. Horizontal reference line is drawn for IQR/median = 30; black markers represent the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the median

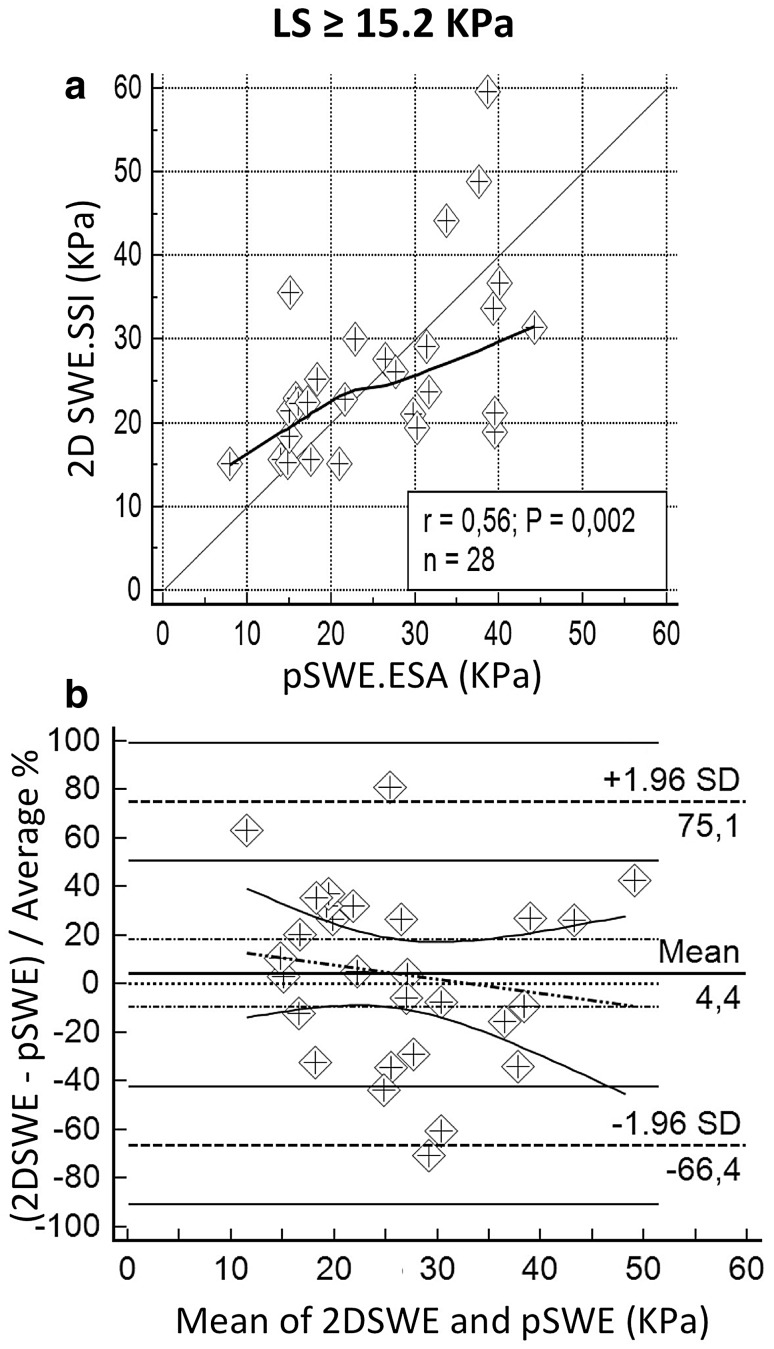

Agreement analysis was also carried out separately for subjects with LS <15.2 kPa (80 cases) and LS ≥15.2 kPa (28 cases). Mean BMI of the two subgroups was, respectively, 24.0 kg/m2 (SD = 2.9) and 25.2 kg/m2 (SD = 3.3), p = 0.102. Notwithstanding a slightly smaller accuracy, the lower LS group showed less scattered measures, resulting in a remarkably better performance in terms of precision (0.737 versus 0.559). These results are summarized in Table 4, Figs. 4 and 5. No systematic deviation to over or underestimation of pSWE.ESA in comparison to 2D SWE.SSI emerged in these subgroups.

Table 4.

Results divided by LS distribution

| 2D SWE.SSI vs pSWE.ESA | ||

|---|---|---|

| LS <15.2 kPa (n = 80) | LS ≥15.2 kPa (n = 28) | |

| 2D SWE.SSI median LS (kPa) | 7.0* | 22.9> |

| Range | 3.9–15.1 | 15.2–59.6 |

| pSWE.ESA median LS (kPa) | 6.9* | 24.7> |

| Range | 3.3–36.0 | 7.9–44.2 |

| Lin’s analysis | ||

| CCC (95% CI) | 0.635 (0.522 to 0.725) | 0.557 (0.240 to 0.767) |

| Precision | 0.737 | 0.559 |

| Accuracy | 0.861 | 0.998 |

| Bland–Altman | ||

| Mean (95% CI) (kPa) | −0.4 (−1.2 to 0.3) | 0.6 (−3.2 to 4.5) |

| LoA (kPa) | −7.2 to 6.3 | −18.9 to 20.2 |

| T test (H0: mean = 0) | p = 0.267 | p = 0.736 |

| Bland–Altman % | ||

| Mean (95% CI) (kPa) | −0.1 (−6.2 to 6.0) % | 4.4 (−9.6 to 18.4) % |

| LoA (kPa) | −53.8 to 53.5% | −66.4 to 75.1% |

| T test (H0: mean = 0) | p = 0.970 | p = 0.528 |

Concordance analysis reported separately for patients under and above the 75th percentile at 2D SWE (15.2 kPa)

* p = 0.935; > p = 0.690

Fig. 4.

Correlation between pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI in patients with stifness at 2D SWE.SSI <15.2 kPa. a, b Respectively show scatter diagram and B&A plot. Scatter diagram is drawn with LOESS line (thick) and reference line (y = x, thin). Legend reports Pearson coefficient (r), p value of Pearson analysis (P) and sample size (n). B&A plots show mean difference (thick horizontal line) and LoA (dashed horizontal lines) with respective CIs (continuous lines); regression line (dashes and points) is shown with CI lines (continuous)

Fig. 5.

Correlation between pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI in patients with stiffness at 2D SWE.SSI <15.2 Kpa (over cirrhosis). a, b Respectively show scatter diagram and B&A plot. Scatter diagram is drawn with LOESS line (thick) and reference line (y = x, thin). Legend reports Pearson coefficient (r), p value of Pearson analysis (P) and sample size (n). B&A plots show mean difference (thick horizontal line) and LoA (dashed horizontal lines) with the respective CIs (continuous lines); regression line (dashes and points) is shown with CI lines (continuous)

Technical SR of pSWE.ESA overall was 56.7% (774/1366) in all 108 subjects and similarly 54.6% (577/1057) in the 81 liver disease patients.

In 80 subjects with LS <15.2 kPa, SR of pSWE.ESA was 62.0% (588/948); conversely, the group with LS ≥15.2 kPa had a lower pSWE.ESA SR of 44.5% (186/418), statistically different (p = 0.001) from subjects with softer liver.

Comparison of SWE machines with Fibroscan

Table 5 shows the characteristics of the 26 liver disease patients and reliable Fibroscan data available. Mean BMI of these patients was 24.8 kg/m2 (SD 3.0). In this group, LS values of both SWE machines were well correlated with those of Fibroscan.

Table 5.

Laboratory data of 26 liver disease patients with Fibroscan data available

| Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 | 2.7–4.7 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.78 | 0.3–4.40 |

| PT (INR) | 1.12 | 0.89–1.96 |

| AST (U/L) | 31 | 12–55 |

| ALT (U/L) | 25 | 10–74 |

| ALP (U/L) | 77 | 43–321 |

| GGT (U/L) | 37 | 14–106 |

| PLTs (units/mm3) | 140 | 38–331 |

PT prothrombin time, INR international normalized ratio, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, GGT gamma-glutamyl transferase, PLTs platelets

Spearman’s rho coefficients were 0.849 for pSWE.ESA and 0.878 for 2D SWE.SSI. Details of the analysis are reported in Table 6 and displayed as scatter plots in Fig. 6.

Table 6.

Results of Spearman analysis of each SWE machine versus Fibroscan as reference in 26 patients with liver disease

| Median LS and range (kPa) | Rho coefficient and 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pSWE.ESA (n = 26) | 11.8 | 0.849 | <0.001 |

| 4.3–44.2 | 0.668–0.930 | ||

| 2D SWE.SSI (n = 26) | 10.7 | 0.878 | <0.001 |

| 4.9–59.6 | 0.743–0.944 | ||

| Fibroscan (n = 26) | 10.8 | ||

| 3.2–55.2 |

CI confidence interval

Fig. 6.

Comparison of LS values measured with SWE machines with Fibroscan as reference. a, b Respectively show scatter diagrams with regression line (thick) and reference line (y = x, thin) of pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI

Role of different intercostal spaces

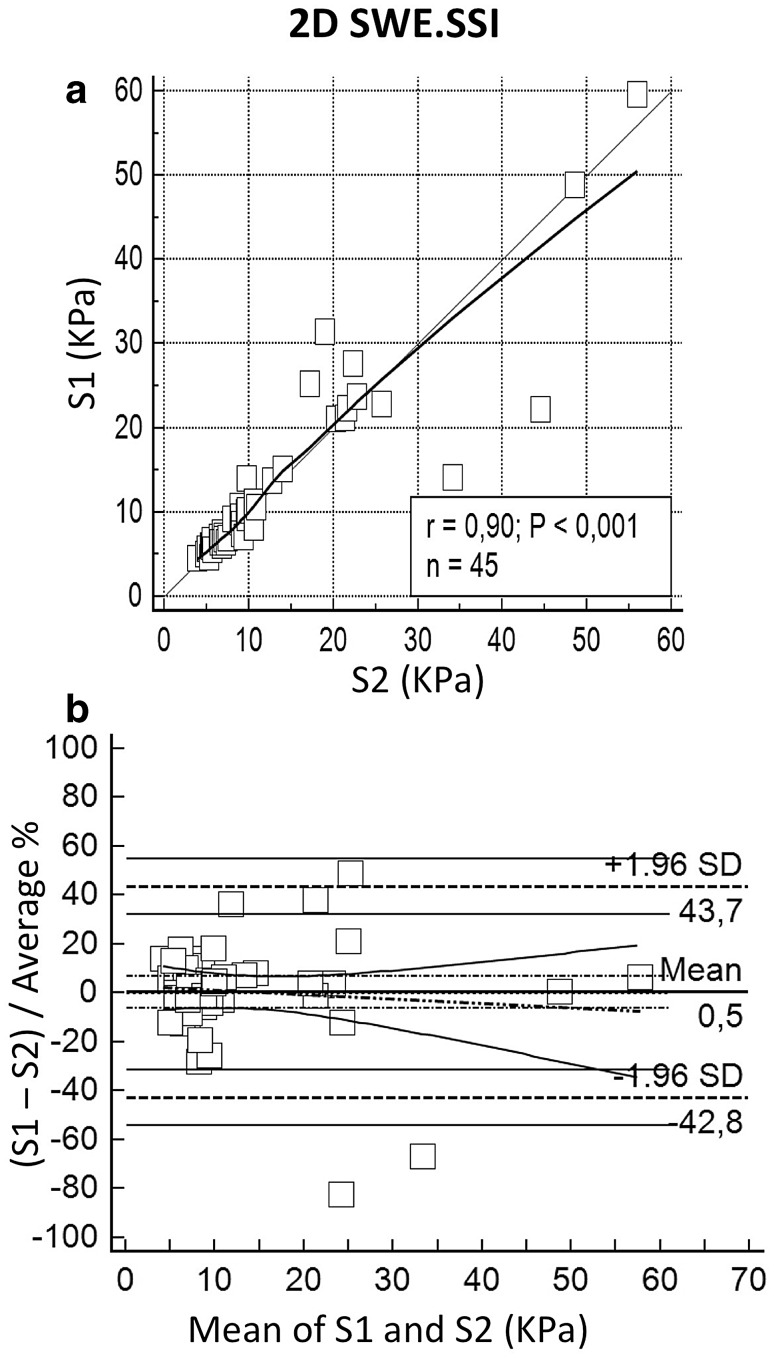

The choice of the intercostal space for liver sampling could represent a factor increasing variability of measures. Accordingly, we compared LS values collected from S1 and S2 on the same patient, separately for each equipment. Precision and accuracy were, respectively, 0.898 and 0.999 for 2D SWE.SSI and 0.911 and 0.933 for pSWE.ESA comparing LS values from S1 with LS values from S2. No systematic deviation between the machines affected the measurements. Complete results are reported in Table 7 and plotted in Fig. 7 and Fig. 8.

Table 7.

Concordance between LS sampled from S1 and S2

| Space 1 vs Space 2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2D SWE.SSI (n = 45) | pSWE.ESA (n = 36) | |

| S1 median LS (kPa) | 9.2* | 8.0> |

| Range | 4.5–59.6 | 3.9–44.2 |

| S2 median LS (kPa) | 9.1* | 7.4> |

| Range | 3.9–55.9 | 3.9–55.9 |

| Lin’s analysis | ||

| CCC (95% CI) | 0.897 (0.821 to 0.942) | 0.904 (0.825 to 0.949) |

| Precision | 0.898 | 0.911 |

| Accuracy | 0.999 | 0.993 |

| Bland–Altman | ||

| Mean (95% CI) (kPa) | −0.2 (−1.7 to 1.4) | 0.5 (−0.9 to 2.0) |

| LoA (kPa) | −10.4 to 13.2 | −7.9 to 8.9 |

| T test (H0: mean = 0) | p = 0.839 | p = 0.485 |

| Bland–Altman % | ||

| Mean (95% CI) | 0.5 (−6.2 to 7.1) % | 5.7 (−3.4 to 14.9) % |

| LoA | −42.8 to 43.7% | −47.4 to 58.9% |

| T test (H0: mean = 0) | p = 0.887 | p = 0.212 |

Results are shown separately for the two SWE equipments

* p = 0.126; > p = 0.273

Fig. 7.

Comparison between LS sampled from two different intercostal spaces (S1 and S2) with 2D SWE.SSI. a, b Respectively show scatter diagram and B&A plot. Scatter diagram is drawn with LOESS line (thick) and reference line (y = x, thin). Legend reports Pearson coefficient (r), p value of Pearson analysis (P) and sample size (n). B&A plots show mean difference (thick horizontal line) and LoA (dashed horizontal lines) with the respective CIs (continuous lines); regression line (dashes and points) is shown with CI lines (continuous)

Fig. 8.

Comparison between LS sampled from two different intercostal spaces (S1 and S2) with pSWE.ESA. a, b Respectively show scatter diagram and B&A plot. Scatter diagram is drawn with LOESS line (thick) and reference line (y = x, thin). Legend reports Pearson coefficient (r), p value of Pearson analysis (P) and sample size (n). B&A plots show mean difference (thick horizontal line) and LoA (dashed horizontal lines) with the respective CIs (continuous lines); regression line (dashes and points) is shown with CI lines (continuous)

Instances of SWE measurements failures

The case excluded from the analysis due to failure of both machines was a 78-year old female with HCV-related cirrhosis (compensated with diuretics administration, Child-Pugh B7) with clinical and ultrasonographic findings of portal hypertension and BMI 28.9 kg/m2. The other four cases in which only pSWE.ESA measurement was unsuccessful were: a 20-year old male affected by cirrhosis from Budd–Chiari syndrome with ascites and portal hypertension (Child-Pugh C11), BMI 19.8 kg/m2; a 68-year old male with HCV-related cirrhosis with portal hypertension without ascites under diuretics (Child-Pugh B7), BMI 29.0 kg/m2; a 72-year old female with HCV-related liver cirrhosis, portal hypertension and ascites (Child-Pugh B9), BMI 22.3 kg/m2; an 80-year old female with HCV-related liver disease without clinical and ultrasonographic signs of cirrhosis, BMI 33.9 kg/m2. 2D SWE.SSI LS was, respectively, 65.9, 27.6, 50.0 and 6.0 kPa. While in the former three patients the machine provided 5/5 valid measurements, valid measurements were 5/8 for the latter case.

Besides the case aforementioned, operators were able to find a suitable area to measure LS with 2D SWE.SSI in all the 108 subjects enrolled in the analysis, resulting in an SR of 100%.

Discussion

The overall degree of agreement between pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI in estimating LS resulted considerable. Notably, the correlation of pSWE.ESA with 2D SWE.SSI was stricter at lower stiffness; conversely in the higher stiffness range the correlation became less strict as the regression line deflects from the 45° reference (resulting in lower accuracy) and the scattering of measures increases (resulting in lower precision). B&A analysis confirms an acceptable global degree of agreement for clinical practice, without systematic deviation between the techniques, although we registered a wider dispersion of data in stiffer livers. In keeping with this evidence, concordance was lower in subjects with LS ≥15.2 kPa. However, this limitation would not prevent the correct fibrosis staging as these subjects would anyhow be diagnosed as cirrhotic. Caution should be only adopted when trying to stratify prognosis in cirrhotic patients according to LS. Moreover, the most clinically relevant information are those to be obtained in patients with liver diseases in the lower range of LS (namely without cirrhosis), where pSWE.ESA appears most reliable.

Our analysis in the 26 patients with liver disease submitted also to Fibroscan showed a strong correlation between both SWE equipments and Fibroscan. Although it cannot be guaranteed that measures of SWE were taken from the same intercostal space as Fibroscan, the stiffness values of SWE machines resulted very similar to those of Fibroscan, supporting the endorsement of these machines in clinical practice whenever Fibroscan would be already adopted.

The less strict relationship between pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI observed in stiff livers might be due to various reasons. One reason might be the technical difference between the equipments, since 2D SWE.SSI allows the operator to freely choose the area for quantification after the stiffness map has been displayed, whereas pSWE.ESA quantification is relatively blind as it is guided only by the B-mode image. Furthermore, in the instance of cirrhosis pSWE may inadvertently target either thicker fibrotic scars or hepatocellular regenerative nodules, which are not recognized on B-mode ultrasonography [18]. This situation might increase the variability of measures taken by pSWE.ESA and might also justify the high IQR to median ratios (Fig. 3). 2D SWE.SSI would be instead less affected since the colour elastography map guides the operator in choosing the site and the size of the ROI, with the possibility to sample a wider region including and thus averaging both thicker scars and regenerative nodules. In keeping with this hypothesis is the fact that when, comparing intercostal spaces S1 versus S2 we found scattered measures when LS was high. Worth to remark, however, that we cannot exclude the possibility that the greater variability of pSWE.ESA in stiffer liver points out an intrinsic limitation of these techniques in measuring stiffer tissues.

Discrepancy among the values sampled scanning the liver through different intercostal spaces is a topic scarcely investigated in the literature [11, 14, 26]. We found a strong concordance between LS values taken from two different intercostal spaces, with high precision and accuracy for both pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI. Noteworthy, even in this case the B&A analysis underlines weaker agreement in the high range of LS. Effect in the instance of pSWE.ESA can be appreciated also considering the deflection of LOESS line in the upper part of the graph, in keeping with the main results of the study. This result is consistent with a heterogeneous involvement of the liver in chronic liver disease, suggesting that a comprehensive evaluation of liver stiffness would probably be carried out at best by averaging the data from more than one intercostal space.

Our study has limitations. The most relevant is the lack of a histology reference, which however has become ethically and practically unfeasible at present, so that alternative solutions must be found. A second limitation could be considered the lack of Fibroscan results in all patients. This information could have made the study more comprehensive, but recent findings suggest that 2D SWE.SSI is not less accurate for fibrosis assessment than Fibroscan, making it a reliable alternative reference standard [17]. At last, the study population of patients with chronic liver disease is limited and not all fibrotic stages are represented in the same rates as in the populations we daily see in our labs. However, this study was not aimed at establishing stiffness thresholds for the various fibrotic stages (for which a larger study population would have been needed), but only at comparing pSWE.ESA with a reference technique. To this end, the study population could be considered acceptable in our view, although larger studies would clearly remain warranted.

In conclusion, the overall degree of concordance of pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI in measuring LS resulted remarkable, with good accuracy and precision in determining LS and slightly poorer results were observed only in overtly cirrhotic patients (2D SWE.SSI LS ≥15.2 kPa), a condition with no impact in the clinical practice as it implies almost no risk of mistaging.

Variability of LS sampled from different intercostal spaces with the same machine was overall limited, but greater in stiffer than in softer livers. This finding might be due to the natural heterogeneity of the liver affected by chronic disease, suggesting that a comprehensive evaluation of liver stiffness could involve assessments across more than one intercostal space, although we could not provide histological evidence to confirm this hypothesis.

Notably, a strong correlation of both pSWE.ESA and 2D SWE.SSI with Fibroscan was observed in a subgroup of patients.

Notwithstanding the considerable performances shown in this preliminary study, it was not aimed at establishing stiffness thresholds for pSWE.ESA able to discriminate different fibrosis stages and studies specifically aimed to this goal remain required.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Lorenzo Mulazzani, Veronica Salvatore, Giulia Allegretti, Francesca Matassoni, Rocco Granata, Alessia Ferrarini and Horia Stefanescu declare no conflict of interest. Fabio Piscaglia: Bayer (advisory board and speaker bureau), Bracco (speaker honoraria), Eisai (advisory board), Esaote (Research Contract), Meda Pharma (speaker bureau).

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent

All the individual participants included were informed about the protocol and then they gave their consent to take part in the study.

Footnotes

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1007/s40477-018-0293-6.

References

- 1.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Rafiq N, Makhlouf H, Younoszai Z, Agrawal R, Goodman Z. Pathologic criteria for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: interprotocol agreement and ability to predict liver-related mortality. Hepatology. 2011;53(6):1874–1882. doi: 10.1002/hep.24268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castera L, Chan H, Arrese M, Afdhal N, Bedossa P, Friedrich-Rust M, Han K, Pinzani M. EASL-ALEH clinical practice guidelines: non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis. J Hepatol. 2015;63(1):237–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardenas A, Mendez-Bocanegra A. Report of the Baveno VI consensus workshop. Ann Hepatol. 2016;15(2):289–290. doi: 10.5604/16652681.1193729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM, Yon S, Fournier C, Mal F, Christidis C, Ziol M, Poulet B, Kazemi F, Beaugrand M, Palau R. Transient elastography: a new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29(12):1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vizzutti F, Arena U, Romanelli RG, Rega L, Foschi M, Colagrande S, Petrarca A, Moscarella S, Belli G, Zignego AL, Marra F, Laffi G, Pinzani M. Liver stiffness measurement predicts severe portal hypertension in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45(5):1290–1297. doi: 10.1002/hep.21665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colecchia A, Montrone L, Scaioli E, Bacchi-Reggiani ML, Colli A, Casazza G, Schiumerini R, Turco L, Di Biase AR, Mazzella G, Marzi L, Arena U, Pinzani M, Festi D. Measurement of spleen stiffness to evaluate portal hypertension and the presence of esophageal varices in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(3):646–654. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedrich-Rust M, Wunder K, Kriener S, Sotoudeh F, Richter S, Bojunga J, Herrmann E, Poynard T, Dietrich CF, Vermehren J, Zeuzem S, Sarrazin C. Liver fibrosis in viral hepatitis: noninvasive assessment with acoustic radiation force impulse imaging versus transient elastography. Radiology. 2009;252(2):595–604. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2523081928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bamber J, Cosgrove D, Dietrich CF, Fromageau J, Bojunga J, Calliada F, Cantisani V, Correas JM, D’Onofrio M, Drakonaki EE, Fink M, Friedrich-Rust M, Gilja OH, Havre RF, Jenssen C, Klauser AS, Ohlinger R, Saftoiu A, Schaefer F, Sporea I, Piscaglia F. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography. Part 1: basic principles and technology. Ultraschall Med. 2013;34(2):169–184. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1335205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosgrove D, Piscaglia F, Bamber J, Bojunga J, Correas JM, Gilja OH, Klauser AS, Sporea I, Calliada F, Cantisani V, D’Onofrio M, Drakonaki EE, Fink M, Friedrich-Rust M, Fromageau J, Havre RF, Jenssen C, Ohlinger R, Saftoiu A, Schaefer F, Dietrich CF. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography. Part 2: clinical applications. Ultraschall Med. 2013;34(3):238–253. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1335375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piscaglia F, Salvatore V, Mulazzani L, Cantisani V, Schiavone C. Ultrasound shear wave elastography for liver disease. A critical appraisal of the many actors on the stage. Ultraschall Med. 2016;37(1):1–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1567037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piscaglia F, Salvatore V, Mulazzani L, Cantisani V, Colecchia A, Di Donato R, Felicani C, Ferrarini A, Gamal N, Grasso V, Marasco G, Mazzotta E, Ravaioli F, Ruggieri G, Serio I, Sitouok Nkamgho JF, Serra C, Festi D, Schiavone C, Bolondi L. Differences in liver stiffness values obtained with new ultrasound elastography machines and Fibroscan: a comparative study. Dig Liver Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferraioli G, Tinelli C, Dal Bello B, Zicchetti M, Filice G, Filice C. Accuracy of real-time shear wave elastography for assessing liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C: a pilot study. Hepatology. 2012;56(6):2125–2133. doi: 10.1002/hep.25936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leung VY, Shen J, Wong VW, Abrigo J, Wong GL, Chim AM, Chu SH, Chan AW, Choi PC, Ahuja AT, Chan HL, Chu WC. Quantitative elastography of liver fibrosis and spleen stiffness in chronic hepatitis B carriers: comparison of shear-wave elastography and transient elastography with liver biopsy correlation. Radiology. 2013;269(3):910–918. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Procopet B, Berzigotti A, Abraldes JG, Turon F, Hernandez-Gea V, Garcia-Pagan JC, Bosch J. Real-time shear-wave elastography: applicability, reliability and accuracy for clinically significant portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;62(5):1068–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiele M, Detlefsen S, Sevelsted Moller L, Madsen BS, Fuglsang Hansen J, Fialla AD, Trebicka J, Krag A. Transient and 2-dimensional shear-wave elastography provide comparable assessment of alcoholic liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):123–133. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassinotto C, Boursier J, de Ledinghen V, Lebigot J, Lapuyade B, Cales P, Hiriart JB, Michalak S, Bail BL, Cartier V, Mouries A, Oberti F, Fouchard-Hubert I, Vergniol J, Aube C. Liver stiffness in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a comparison of supersonic shear imaging, FibroScan, and ARFI with liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2016;63(6):1817–1827. doi: 10.1002/hep.28394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrmann E, de Ledinghen V, Cassinotto C, Chu WC, Leung VY, Ferraioli G, Filice C, Castera L, Vilgrain V, Ronot M, Dumortier J, Guibal A, Pol S, Trebicka J, Jansen C, Strassburg C, Zheng R, Zheng J, Francque S, Vanwolleghem T, Vonghia L, Manesis EK, Zoumpoulis P, Sporea I, Thiele M, Krag A, Cohen-Bacrie C, Criton A, Gay J, Deffieux T, Friedrich-Rust M. Assessment of biopsy-proven liver fibrosis by 2D-shear wave elastography: an individual patient data based meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017 doi: 10.1002/hep.29179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bedossa P, Dargere D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38(6):1449–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dietrich CF, Bamber J, Berzigotti A, Bota S, Cantisani V, Castera L, Cosgrove D, Ferraioli G, Friedrich-Rust M, Gilja OH, Goertz RS, Karlas T, de Knegt R, de Ledinghen V, Piscaglia F, Procopet B, Saftoiu A, Sidhu PS, Sporea I, Thiele M. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of liver ultrasound elastography, update 2017 (long version) Ultraschall Med. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Onofrio M, Crosara S, De Robertis R, Canestrini S, Demozzi E, Gallotti A, Pozzi Mucelli R. Acoustic radiation force impulse of the liver. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(30):4841–4849. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i30.4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bercoff J, Tanter M, Fink M. Supersonic shear imaging: a new technique for soft tissue elasticity mapping. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2004;51(4):396–409. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2004.1295425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colecchia A, Colli A, Casazza G, Mandolesi D, Schiumerini R, Reggiani LB, Marasco G, Taddia M, Lisotti A, Mazzella G, Di Biase AR, Golfieri R, Pinzani M, Festi D. Spleen stiffness measurement can predict clinical complications in compensated HCV-related cirrhosis: a prospective study. J Hepatol. 2014;60(6):1158–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin LI. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics. 1989;45(1):255–268. doi: 10.2307/2532051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bland JM, Altman DG. Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8(2):135–160. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sellen D (1995) Report of a WHO expert committee. physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. WHO Technical Report Series No. 854. WHO, Geneva [PubMed]

- 26.Deffieux T, Gennisson JL, Bousquet L, Corouge M, Cosconea S, Amroun D, Tripon S, Terris B, Mallet V, Sogni P, Tanter M, Pol S. Investigating liver stiffness and viscosity for fibrosis, steatosis and activity staging using shear wave elastography. J Hepatol. 2015;62(2):317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]