Abstract

Aspergillus section Aspergillus (formerly the genus Eurotium) includes xerophilic species with uniseriate conidiophores, globose to subglobose vesicles, green conidia and yellow, thin walled eurotium-like ascomata with hyaline, lenticular ascospores. In the present study, a polyphasic approach using morphological characters, extrolites, physiological characters and phylogeny was applied to investigate the taxonomy of this section. Over 500 strains from various culture collections and new isolates obtained from indoor environments and a wide range of substrates all over the world were identified using calmodulin gene sequencing. Of these, 163 isolates were subjected to molecular phylogenetic analyses using sequences of ITS rDNA, partial β-tubulin (BenA), calmodulin (CaM) and RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPB2) genes. Colony characteristics were documented on eight cultivation media, growth parameters at three incubation temperatures were recorded and micromorphology was examined using light microscopy as well as scanning electron microscopy to illustrate and characterize each species. Many specific extrolites were extracted and identified from cultures, including echinulins, epiheveadrides, auroglaucins and anthraquinone bisanthrons, and to be consistent in strains of nearly all species. Other extrolites are species-specific, and thus valuable for identification. Several extrolites show antioxidant effects, which may be nutritionally beneficial in food and beverages. Important mycotoxins in the strict sense, such as sterigmatocystin, aflatoxins, ochratoxins, citrinin were not detected despite previous reports on their production in this section. Adopting a polyphasic approach, 31 species are recognized, including nine new species. ITS is highly conserved in this section and does not distinguish species. All species can be differentiated using CaM or RPB2 sequences. For BenA, Aspergillus brunneus and A. niveoglaucus share identical sequences. Ascospores and conidia morphology, growth rates at different temperatures are most useful characters for phenotypic species identification.

Key words: Ascomycota, Eurotiales, Aspergillaceae, Multi-gene phylogeny, Extrolites, Aspergillus proliferans, Eurotium amstelodami

Taxonomic novelties: Aspergillus aerius A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson; A. aurantiacoflavus Hubka, A.J. Chen, Jurjević & Samson; A. caperatus A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson; A. endophyticus Hubka, A.J. Chen, & Samson; A. levisporus Hubka, A.J. Chen, Jurjević & Samson; A. porosus A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson; A. tamarindosoli A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson; A. teporis A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson; A. zutongqii A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson

Introduction

Aspergillus subgenus Aspergillus, typified with A. glaucus (L.) Link, was introduced to include Aspergillus species with uniseriate conidiophore heads with hyaline, brownish or greenish stipes, and slightly inflated to subglobose vesicles and green conidia in mass (Gams et al. 1985). The subgenus contains two sections, namely sections Aspergillus (Aspergillus glaucus group Thom and Raper, 1941, Thom and Raper, 1945, Raper and Fennell, 1965) and Restricti (Aspergillus restrictus group Raper & Fennell 1965). The main difference of these two sections is that species in sect. Aspergillus readily produce a sexual state in culture (homothallic) and this sexual morph was, in the dual name nomenclature system, classified in the genus Eurotium (Malloch and Cain, 1972, Pitt, 1985). While the majority of species in sect. Restricti are asexually reproducing, one exception is A. halophilicus, which produces a eurotium-like sexual state (Christensen et al. 1959, Peterson et al. 2008). Peterson (2008) examined Aspergillus phylogenetically using β-tubulin (BenA), calmodulin (CaM), ID region of rDNA (ITS and partial LSU) and RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPB2), and showed that sections Aspergillus and Restricti formed a monophyletic subgenus Aspergillus. The monophyly of both sections was recently confirmed using a larger data set by Sklenář et al. (2017). Houbraken & Samson (2011) assessed relationships in the Trichocomaceae using a multigene phylogeny (RPB1, RPB2, Tsr1 and Cct8) and showed that Aspergillus and its sexual states formed a monophyletic clade closely related to Penicillium. This was again confirmed using a 25-gene phylogeny (Houbraken et al. 2014). Pitt & Taylor (2014) on the other hand, re-examined and analysed data from Houbraken and Samson (2011), and claimed that Penicillium could be included in a very broad concept of Aspergillus, which would only be monophyletic if Penicillium was included. This was partly caused by Aspergillus paradoxus, A. malodoratus and A. crystallinus, which were at that time still classified in Aspergillus, but currently in Penicillium. Similarly, Penicillium inflatum was combined in Aspergillus as Aspergillus inflatus (Visagie et al. 2014b, Samson et al. 2014). Furthermore, Pitt and Taylor, 2014, Pitt and Taylor, 2016 proposed to maintain the genus Eurotium for subgenus Aspergillus and subdivided Aspergillus into several smaller genera based on the corresponding sexual names. Most recently, Kocsubé et al. (2016) brought strong evidence that Aspergillus and Penicillium are monophyletic based on a robust multiple gene phylogenetic analyses and extrolite profiles. These findings rejected the hypothesis of Aspergillus being a paraphyletic genus (Pitt and Taylor, 2014, Pitt and Taylor, 2016), and were in agreement with the previous studies of Houbraken & Samson (2011) and Houbraken et al. (2014).

To avoid instability and nomenclatural confusion, the broad concept of Aspergillus was chosen by a majority of the International Commission of Penicillium and Aspergillus (ICPA) on April 11, 2012. Consequently, Hubka et al. (2013a) transferred all Eurotium taxa to Aspergillus. This treatment is widely accepted. Subsequently five species producing a eurotium-like sexual state, namely A. cumulatus, A. mallochii, A. megasporus, A. osmophilus and A. sloanii were introduced in sect. Aspergillus and Aspergillus names preferred over Eurotium by most authors (Asgari et al., 2014, Kim et al., 2014, Visagie et al., 2014a, Visagie et al., 2017). Before sequence data became widely available, the taxonomy of sect. Aspergillus was based on morphological characters. Ascospore pattern, shape and size were considered the most important characters distinguishing species, whereas the conidial apparatus and mycelial pigmentation provide valuable additional information (Thom and Raper, 1941, Thom and Raper, 1945, Raper and Fennell, 1965). Raper (1957) emphasized that in some strains the sexual state is dominating, while in others it is the asexual state, which has significant influence on the appearance of colonies. Blaser (1975) found that morphology and size of ascospores, surface ornamentation and colour of conidia are dependent on the temperature and water activity of cultivation media and thus reduced some species to synonyms. Samson (1979) compiled the sect. Aspergillus species published since Raper and Fennell's treatment in 1965, and synonymized six species under earlier names. Pitt (1985) reappraised the nomenclature and taxonomy of Eurotium (sect. Aspergillus), and accepted seven species based on the distinct nature of their ascospores. Kozakiewicz (1989) focused on scanning electron microscope (SEM) examinations of conidia and ascospores in her treatment of the group. Based on conidial ornamentations, four conidial morphotypes were identified, namely aculeate, tuberculate, lobate-reticulate and microtuberculate. Within each group, characters of equatorial crests, furrow and convex wall ornamentation are important diagnostic features. It was shown that some species previously considered conspecific according to light microscopy, e.g. A. cristatus (= Eurotium cristatum) and A. intermedius (= E. intermedium), show distinct conidial ornamentation in SEM and deserve to be recognized as separate species (Kozakiewicz 1989). Hubka et al. (2013a) studied the phylogeny of sect. Aspergillus based on ID region, BenA, CaM and RPB2 sequences, and accepted 17 species based on Genealogical Concordance Phylogenetic Species Recognition (GCPSR) approach.

Members of sect. Aspergillus are generally referred to as osmo-, xero- or halotolerant. They have a world-wide distribution and are common in indoor air, house dust, cereals, food products containing high concentrations of sugar, such as syrups, jams and jellies, salted meat products, semi-dry foods, feeds, leather goods and so on (Raper and Fennell, 1965, Blaser, 1975, Chelkowski et al., 1987, Pitt and Hocking, 2009, Samson et al., 2010, Greco et al., 2015). Species in this section are able to initiate growth at minimum moisture levels, thus establishing bridgeheads and facilitating the invasion of slightly less xerophilic molds (Semeniuk et al., 1947, Raper and Fennell, 1965, Kozakiewicz, 1989). Some species are involved in food manufacturing. Aspergillus cristatus or “Golden Flower Fungus” is used in the production of Fuzhuan brick tea in China (Wen, 1990, Qi and Sun, 1990, Xu et al., 2011); Aspergillus pseudoglaucus (= Eurotium repens) is used as a starter culture in the manufacturing of katsuobushi and fish sauce (Hayakawa et al., 1993, Dimici and Wada, 1994); A. pseudoglaucus, A. chevalieri and A. montevidensis are frequently isolated from meju (dried fermented soybeans); two newly described species A. cibarius and A. cumulatus are also isolated from meju or meju fermentation related environment (Hong et al., 2011, Hong et al., 2012, Kim et al., 2014). Aspergillus chevalieri, A. cristatus, A. glaucus, A. montevidensis, A. proliferans, A. pseudoglaucus and A. ruber have been reported from feedstuffs very often (Pitt and Hocking, 2009, Samson et al., 2010, Greco et al., 2015). These species have also been reported from other habitats and substrates. Aspergillus cristatus, A. glaucus, A. pseudoglaucus and A. ruber were listed as marine-derived (Li et al., 2004a, Li et al., 2004b, Li et al., 2006, Li et al., 2008a, Li et al., 2008b, Li et al., 2009, Li et al., 2010, Wang et al., 2006, Wang et al., 2007c, Du et al., 2007, Du et al., 2008, Du et al., 2012, Du et al., 2014, Smetanina et al., 2007, Tao et al., 2009, Gomes et al., 2012, Yan et al., 2012, Sun et al., 2013, Tang et al., 2014, Meng et al., 2015) and A. brunneus, A. chevalieri, A. cristatus, A. glaucus, A. intermedius, A. montevidensis, A. niveoglaucus, A. pseudoglaucus, A. ruber and A. xerophilus have been reported from soil (Guarro et al. 2012). However, sea-water and soil are matrices rather than habitats, usually of high water activity, where these fungi cannot grow or compete with other fungi. Species in sect. Aspergillus are not considered as important pathogens, although A. glaucus, A. chevalieri and A. montevidensis (= Eurotium amstelodami) have been reported from cases of superficial infections and sporadic invasive infections (de Hoog et al., 2000, Reboux et al., 2001, Roussel et al., 2004, Summerbell et al., 2005, Hubka et al., 2012).

Species of sect. Aspergillus produce many extrolites such as flavoglaucin, auroglaucin, isotetrahydroauroglaucin, neoechinulins A and B, echinulin, preechinulin, neochinulin E, epiheveadride and questin (Slack et al., 2009, Greco et al., 2015). Production of the potentially toxic echinulin has been reported from various strains of A. montevidensis (= E. amstelodami) (Allen, 1972, Gatti and Fuganti, 1979) and A. pseudoglaucus (= E. repens) (Smetanina et al. 2007). Other so-called toxins such as flavoglaucin and auroglaucin co-occur in various taxa of sect. Aspergillus, along with isotetrahydroauroglaucin in some A. montevidensis (= E. amstelodami) and A. ruber (= E. rubrum) strains (Slack et al. 2009). Interestingly, none of the compounds produced by these fungi have been classified as real mycotoxins, as the definition of the word mycotoxin is secondary metabolites (or extrolites) produced by filamentous fungi that are toxic to human beings and other vertebrates when introduced in small amounts via a natural route (orally, through pulmonary tract or skin) (Bennett & Klich 2003). On the other hand, the small molecule extrolites, such as dihydroauroglaucin (DAG), tetrahydroauroglaucin (TAG), anthraquinone derivatives, etc. produced by sect. Aspergillus species are antioxidant, and may even be beneficial to health (Ishikawa et al., 1985, Li et al., 2004a, Li et al., 2009, Miyake et al., 2009, Meng et al., 2016). Reports of sect. Aspergillus species producing true mycotoxins such as aflatoxins, ochratoxin A and sterigmatocystin were proved to be incorrect (Frisvad et al. 2007).

The aim of this study is to provide a taxonomic revision of sect. Aspergillus using a polyphasic approach. Phylogenetic relationships between sect. Aspergillus members were investigated using a combined data set (BenA, CaM and RPB2 sequences), and comparison of single-gene phylogenies was executed to determine tentative species boundaries based on genealogical concordance principle. Furthermore, phenotypic features including macro- and micro-morphology, ecophysiology and extrolite profiles are included in the polyphasic approach. Finally, the details on the identification of world-wide indoor environment strains have been included here.

Material and methods

Fungal strains

Strains used in this study were obtained from: 1) CBS, Culture Collection of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands; 2) CGMCC, China General Microbiological Culture Collection Centre, Beijing, China; 3) NRRL, Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, Peoria, Illinois, USA; 4) KACC, Korean Agricultural Culture Collection, Wanju, South Korea; 5) CCF, Culture Collection of Fungi, Prague, Czech Republic; 6) CCM (F-), Czech Collection of Microorganisms, Brno, Czech Republic; 7) IBT, the culture collection of Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark; 8) DAOMC, Canadian Collection of Fungal Cultures, at the Ottawa Research and Development Centre – Agriculture and Agri-Food, Ottawa, Canada; and 9) BCCM/IHEM, Belgian Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms. Strains deposited in the working collection of the Applied and Industrial Mycology department (DTO) housed at the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, were also included in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Section Aspergillus strains used in phylogenetic analyses.

| Species | Strain nr.1 | Source | GenBank accession nr. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | BenA | CaM | RPB2 | |||

| Aspergillus aerius | CBS 141771T = DTO 241-G7 = IBT 34446 | The Netherlands, air treatment system in production plant, 2013, J. Houbraken | LT670916 | LT670990 | LT670991 | LT670992 |

| A. appendiculatus | CBS 374.75T = IMI 278374 = FRR 2793 = JCM 1566 = IBT 34507 | Switzerland, Stäfa, smoked sausage, 1971, P. Blaser | HE615132 | HE801333 | HE801318 | HE801307 |

| CBS 101746 = CGMCC 3.04673 (AS 3.4673) (ex-type of A. aridicola) | China, Tibet, sheep dung, H.Z. Kong & Z.T. Qi | HE615133 | HE801334 | HE801319 | HE801308 | |

| A. aurantiacoflavus | CBS 141930T = EMSL No. 2903 = CCF 5393 = DTO 355-I1 = IBT 34485 | USA, California, San Diego, baby carrier – backpack, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670917 | LT670993 | LT670994 | LT670995 |

| EMSL No. 2693 = CCF 5391 = DTO 355-H7 | USA, IL, Chicago, rubber toy imported from China, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670918 | LT670996 | LT670997 | LT670998 | |

| EMSL No. 3024 = CCF 5394 = DTO 355-H9 | USA, New Jersey, Cherry Hill, cake spread, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670919 | LT670999 | LT671000 | LT671001 | |

| A. brunneus | CBS 112.26T = CBS 524.65 = IBT 5341 = NRRL 131 = NRRL 134 = ATCC 1021 = IFO 5862 = IMI 211378 = QM 7406 = Thom 4481 = Thom 5633.4 = WB 131 = CCF 5587 (neotype of A. echinulatus) | USA, California, fruit (Ficus carica), M.B. Church | EF652060 | EF651907 | EF651998 | EF651939 |

| DTO 357-A1 = KAS7575 | Canada, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie | LT670920 | LT671002 | LT671003 | LT671004 | |

| NRRL 133 = CCF 5586 | Unknown source, G. Smith | EF652061 | EF651908 | EF651999 | EF651940 | |

| NRRL 124 = CBS 113.27 = CCF 5585 (ex-type of A. medius) | Unknown source, W. McRae | EF652056 | EF651904 | EF651997 | EF651938 | |

| DTO 197-B3 = CBS 117328 | Canada, Manitoba, M. Desjardins | LT670921 | LT671005 | LT671006 | LT671007 | |

| A. caperatus | CBS 141774T = DTO 337-E6 = IBT 34451 | South Africa, Robben Island, soil, 2015, M. Meijer | LT670922 | LT671008 | LT671009 | LT671010 |

| A. chevalieri | CBS 522.65T = NRRL 78 = ATCC 16443 = IMI 211382 = NRRL A-7803 = Thom 4125.3 = WB 78 = IBT 5680 (neotype of A. equitis) | USA, coffee beans, 1916, C. Thom | EF652068 | EF651911 | EF652002 | EF651954 |

| NRRL 79 | USA, Indiana, Indianapolis, unknown source, Dr. Adams | EF652069 | EF651912 | EF652003 | EF651955 | |

| NRRL 4755 | USA, culture contamination, D.I. Fennell | EF652071 | EF651913 | EF652004 | EF651956 | |

| CCF 3291 = DTO 355-B6 | Czech Republic, Brno, rice, 1999, V. Ostrý | FR727116 | HE578085 | HE578099 | HE801314 | |

| CCF 1676 = DTO 355-B7 | Czech Republic, Prague, semolina, 1979, V. Muzikář | LT670923 | LT671011 | LT671012 | LT671013 | |

| CCF 4788 = KACC 47145 = DTO 355-B8 | South Korea, soybeans, 2012, D.H. Kim | LT670924 | LT671014 | LT671015 | LT671016 | |

| CGMCC 3.06132 = DTO 348-G5 | China, Tibet, soil, 2001 | LT670925 | LT671017 | LT671018 | LT671019 | |

| DTO 238-E3 | Unknown source, S. Suhendriani | LT670926 | LT671020 | LT671021 | LT671022 | |

| CBS 141769 = DTO 088-D7 | Madagascar, soil, 2008, J. Houbraken | LT670927 | LT671023 | LT671024 | LT671025 | |

| CGMCC 3.06492 = DTO 348-H3 | China, Yunnan, moldy peel, 2001 | LT670928 | LT671026 | LT671027 | LT671028 | |

| DTO 092-D3 | Madagascar, soil, 2008, J. Houbraken | LT670929 | LT671029 | LT671030 | LT671031 | |

| A. cibarius | KACC 46346T = DTO 197-D3 = IBT 32307 = CCF 4783 | South Korea, Icheon, meju, 2011, S.B. Hong | JQ918177 | JQ918180 | JQ918183 | JQ918186 |

| CCF 4098 = NRRL 62493 = DTO 354-I8 | Czech Republic, Prague, toenail of 56-year-old woman, 2010, P. Lysková | FR848828 | FR837968 | FR837973 | FR837979 | |

| CCF 4235 = NRRL 62492 = DTO 354-I7 | Czech Republic, Prague, toenail of 63-year-old man, 2012, P. Lysková | HE801341 | HE801330 | HE801324 | HE801313 | |

| CCF 4264 = DTO 354-I9 | Spain, Nerja cave, near Málaga, cave sediment (entrance chambre), 2011, A. Nováková | HE974462 | HE974436 | HE806186 | HE974428 | |

| KACC 49766 = CCF 4784 | The Netherlands, black bean, 2012, M. Meijer | LT670930 | LT671032 | LT671033 | LT671034 | |

| EMSL No. 1652 = CCF 5385 = DTO 355-G6 | USA, Pennsylvania, child's shoes, 2012, Ž. Jurjević | LT670931 | LT671035 | LT671036 | LT671037 | |

| EMSL No. 2498 = CCF 5383 = DTO 355-G7 | USA, Washington DC, chocolate glazed frosted donut, 2014, Ž. Jurjević | LT670932 | LT671040 | LT671041 | LT671042 | |

| EMSL No. 2865 = CCF 5384 = DTO 355-G8 | USA, California, Danville, chocolate chip cookies, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670933 | LT671043 | LT671044 | LT671045 | |

| CGMCC 3.06498 = DTO 348-H7 | China, Hebei, soil, 2001 | LT670934 | LT671046 | LT671047 | LT671048 | |

| CGMCC 3.00450 = DTO 348-B5 | China, 1952 | LT670935 | LT671049 | LT671050 | LT671051 | |

| A. costiformis | CBS 101749T = CGMCC 3.04664 (AS 3.4664) = DTO 348-D8 = IBT 34456 = IBT 33662 | China, Hebei, moldy paper-box, 1992, H.Z. Kong | HE615136 | HE801338 | HE801320 | HE801309 |

| CCF 4097 = NRRL 62483 = DTO 354-I3 | Czech Republic, Prague, toenail of 5-year-old boy, 2010, P. Lysková | FR837960 | FR837970 | FR837974 | FR837978 | |

| DTO 326-B4 | The Netherlands, cellophane, 2015, J. Houbraken | LT670936 | LT671052 | LT671053 | LT671054 | |

| CGMCC 3.06520 = DTO 348-I5 | China, Hebei, moldy box, 2001 | LT670937 | LT671055 | LT671056 | LT671057 | |

| A. cristatus | CBS 123.53T = NRRL 4222 = ATCC 16468 = BCRC 33090 = FRR 1167 = IBT 5355 = IHEM 5619 = IMI 172280 = JCM 1569 = MUCL 15644 = NRRL 4222 = WB 4222 = CCF 5591 (ex-type of A. cristatellus) | South Africa, unknown, 1953, H.J. Swart | EF652078 | EF651914 | EF652001 | EF651957 |

| IHEM 2423 = DTO 355-B3 | Zaire, Kinshasa, soil, 1984 | LT670938 | LT671058 | LT671059 | LT671060 | |

| CCF 4701 = DTO 355-B1 | China, Hunan, tea block, 2013, Q.L. Pan & L. Wang | KF923732 | KF923737 | KF923741 | KF923734 | |

| CCF 4702 = DTO 355-B2 | China, Guangxi, tea block, 2013, Q.L. Pan & L. Wang | KF923733 | KF923739 | LT714711 | KF923736 | |

| CGMCC 3.06081 = DTO 348-E9 | China, Hubei, soil, 2001 | LT670939 | LT671061 | LT671062 | LT671063 | |

| A. cumulatus | KACC 47316T = DTO 303-D9 = IBT 34470 = IBT 33670 | South Korea, Anseong, rice straw used in meju fermentation | KF928303 | KF928297 | KF928300 | KF928294 |

| KACC 47513 = DTO 303-D8 | South Korea, air of a meju fermentation room | KF928304 | KF928298 | KF928301 | KF928295 | |

| KACC 47514 | South Korea, air of a meju fermentation room | KF928305 | KF928299 | KF928302 | KF928296 | |

| EMSL No. 2827 = CCF 5376 = DTO 355-G9 | USA, New York, Bronx, bedroom ceiling, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670940 | LT671064 | LT671065 | LT671066 | |

| A. endophyticus | CBS 141766T = DTO 354-I2 = CCF 5345 = IBT 34511 | Czech Republic, Prague, Stromovka park, endophyte of Acer pseudoplatanus, 2013, I. Kelnarová | LT670941 | LT671067 | LT671068 | LT671069 |

| A. glaucus | CBS 516.65T = NRRL 116 = ATCC 16469 = DTO 197-A1 = IBT 32295 = IMI 211383 = LCP 64.1859 = Thom 5629.C = WB 116 | USA, Washington DC, unpainted board (K.B. Raper's residence), 1938, K.B. Raper | EF652052 | EF651887 | EF651989 | EF651934 |

| NRRL 117 = DTO 355-B4 = CCF 5582 (ex-type of A. mangini) | USA, Washington DC, unpainted board (K.B. Raper's basement), 1938, K.B. Raper | EF652053 | EF651888 | EF651990 | EF651935 | |

| EMSL No. 2529 = CCF 5381 = DTO 355-H1 | Puerto Rico, Bayamon, office, air, 2014, Ž. Jurjević | LT670942 | LT671070 | LT671071 | LT671072 | |

| NRRL 120 = 117.46 = CBS 532.65 = CCF 5583 (ex-type of A. umbrosus) | USA, coffee beans, 1925, F.A. McCormick | EF652054 | EF651889 | EF651991 | EF651936 | |

| NRRL 121 = DTO 355-B5 = CCF 5584 | Unknown source | EF652055 | EF651890 | EF651992 | EF651937 | |

| EMSL No. 3317 = CCF 5382 = DTO 355-H2 | USA, New York, Ulster Park, bedroom, settle plates, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670943 | LT671073 | LT671074 | LT671075 | |

| A. intermedius | CBS 523.65T = NRRL 82 = ATCC 16444 = DSM 2830 = IBT 5677 = IMI 089278ii = IMI 89278 = LSHBBB 107 = LSHTM 107 = QM 7403 = Thom 5612.107 = WB 82 = CCF 5581 | UK, cotton yarn, 1927, G. Smith | EF652074 | EF651892 | EF652012 | EF651958 |

| NRRL 84 | Unknown source | EF652070 | EF651893 | EF652013 | EF651959 | |

| NRRL 4817 = DTO 355-B9 = IFO 5322 = IMI 313754 = JCM 23051 = CCF 5608 | Unknown country, butter | EF652072 | EF651894 | EF652014 | EF651960 | |

| NRRL 25823 | USA, IL, Peoria, soy protein, A.J. Moyer | EF652073 | EF651895 | EF652015 | EF651961 | |

| CBS 377.75 (ex-type of A. spiculosus) | Spain, Badajoz, soil, P. Blaser | HE974459 | HE974432 | HE974437 | HE974425 | |

| CCF 127 = DTO 354-I5 | China, industrial material, 1955, V. Zánová | HE578060 | HE974431 | HE578100 | HE974426 | |

| CCF 4681 = DTO 354-I6 | Czech Republic, Prague, sputum of 55-year-old woman, 2013, P. Lysková | LT670944 | LT671076 | LT671077 | LT671078 | |

| CCF 5377 = DTO 355-G5 | Czech Republic, Prague, air sampler, surgical operating room, 2014, A. Ešnerová | LT670945 | LT671079 | LT671080 | LT671081 | |

| CGMCC 3.03968 = DTO 348-D6 | China, unknown source, 1969 | LT670946 | LT671082 | LT671083 | LT671084 | |

| CGMCC 3.00664 = DTO 348-C1 | Czech Republic, unknown source, 1956 | LT670947 | LT671085 | LT671086 | LT671087 | |

| A. leucocarpus | CBS 353.68T = IBT 5350 = IMI 278375 = NRRL 3497 = QM 9365 = QM 9707 = CCF 5590 | Germany, Giessen, dried sausage, R. Hadlok | EF652087 | EF651925 | EF652023 | EF651972 |

| DTO 357-A2 = KAS7576 | Canada, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie | LT670948 | LT671088 | LT671089 | LT671090 | |

| DTO 174-I5 | Madagascar, vanilla sticks, 2012, J. Houbraken | LT670949 | LT671091 | LT671092 | LT671093 | |

| A. levisporus | CBS 141767T = DTO 355-G4 = EMSL No. 3211 = CCF 5378 = IBT 34512 | USA, Missouri, Saint Louis, bedroom, wood base, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670950 | LT671094 | LT671095 | LT671096 |

| A. mallochii | CBS 141928T = DTO 357-A5 = KAS7618 = DAOMC 146054 | USA, California, San Mateo, pack rat dung, D. Malloch | KX450907 | KX450889 | KX450902 | KX450894 |

| CBS 141776 = DTO 343-G3 | The Netherlands, chocolat miroir, 2015 | KX450908 | KX450890 | KX450903 | KX450895 | |

| A. megasporus | CBS 141929T= DTO 356-H7 = KAS6176 = DAOMC 250799 | Canada, Nova Scotia, Wolfville, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie | KX450910 | KX450892 | KX450905 | KX450897 |

| CBS 141772 = DTO 048-I3 | The Netherlands, Dutch chocolate butter, 2007, M. Meijer | KX450911 | KX450893 | KX450906 | KX450898 | |

| DTO 356-H1 = KAS5973 = DAOMC 250800 | Canada, New Brunswick, Little Lepreau, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie | KX450909 | KX450891 | KX450904 | KX450896 | |

| A. montevidensis | CBS 491.65T = NRRL 108 = ATCC 10077 = IBT 5685 = IHEM 3337 = IMI 172290 = NRRL 109 = QM 7423 = Thom 5290 = Thom 5633.24 = WB 108 | Uruguay, Montevideo, tympanic membrane of human ear, 1932, R.V. Talice & J.E. MacKinnon | EF652077 | EF651898 | EF652020 | EF651964 |

| NRRL 89 | Unknown source | EF652075 | EF651896 | EF652016 | EF651962 | |

| NRRL 90 = CBS 518.65 (ex-type of A. hollandicus) | USA, unknown source, ∼1910 | EF652076 | EF651897 | EF652017 | EF651963 | |

| NRRL 4716 | USA, Missouri, Columbia, candied grapefruit rind, D.I. Fennell | EF652079 | EF651899 | EF652018 | EF651965 | |

| NRRL 25850 | USA, IL, Peoria, refrigerated bread dough, R. Graves | EF652082 | EF651900 | EF652021 | EF651966 | |

| NRRL 35697 | USA, IL, Chicago, nasal swab | EF652084 | EF651902 | EF652022 | EF651968 | |

| NRRL A-13891 = CBS 410.65 (ex-type of A. heterocaryoticus) | Mexico, Oryza sativa kernel, 1963, C.R. Benjamin | EU021619 | EU021670 | EU021687 | EU021659 | |

| CBS 651.74 = ATCC 24717 = IMI 174724 = VKM F-1760 (ex-type of A. vitis) | Kazakhstan, Alma-Ata, ex grapes, 1968, L.A. Beljakova | HE974460 | HE974433 | HE974441 | HE974424 | |

| CCF 3998 | Czech Republic, Prague, neck skin of 78-year-old woman, 2008, M. Skořepová | FR727117 | HE974434 | FR751447 | HE974418 | |

| CCF 4069 | Czech Republic, heel skin of 32-year-old man, Prague, 2007, M. Skořepová | FR839679 | FR775356 | HE974440 | HE974419 | |

| CCF 4070 | Czech Republic, fingernail of 32-year-old woman, Prague, 2007, M. Skořepová | FR848825 | FR775335 | FR751442 | HE974420 | |

| CCF 4071 | Czech Republic, Prague, thigh and neck skin of 42-year-old woman, 2010, P. Lysková | FR839680 | HE974435 | FR751449 | HE974421 | |

| CCF 4248 | Czech Republic, Skrbeň, window sill, 1997, A. Kubátová | HE974461 | HE801339 | HE974442 | HE974422 | |

| EMSL No. 2934 = CCF 5379 = DTO 355-H3 | USA, PA, Mahanoy City, bedroom, settle plates, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670951 | LT671097 | LT671098 | LT671099 | |

| CBS 111.52 = DTO 351-C9 | Suriname, plywood, M.B. Schol-Schwarz | LT670952 | LT671100 | LT671101 | LT671102 | |

| DTO 147-I4 | Hungary, indoor air, 2014, M. Meijer | LT670953 | LT671103 | LT671104 | LT671105 | |

| CGMCC 3.03888 = DTO 348-D3 | China, mite, 1969 | LT670954 | LT671106 | LT671107 | LT671108 | |

| A. neocarnoyi | CBS 471.65T = NRRL 126 = ATCC 16924 = IBT 6016 = IMI 172279 = LSHTM A32 = QM 7402 = Thom 5612.A32 = WB 126 = DTO 196-H6 = CCF 5588 | Unknown source, P. Biourge | EF652057 | EF651903 | EF651985 | EF651942 |

| EXF-10029 = DTO 357-E2 | Slovenia, Ljubljana, Slovene Ethnographic museum, air at the sampling of shaman statue originating from Mali, 2016, P. Zalar | LT670955 | LT671109 | LT671110 | LT671111 | |

| A. niveoglaucus | CBS 114.27T = CBS 517.65 = NRRL 127 = ATCC 10075 = BCRC 33096 = CGMCC 3.04374 = FRR 927 = IBT 5356 = IMI 32050 = JCM 1578 = LSHBA 16 = NRRL 129 = NRRL 130 = QM 1977 = Thom 5612.A16 = Thom 5633 = Thom 5633.7 = Thom 7053.2 = UAMH 6591 = WB 127 = WB 130 = CCF 5589 (lectotype of A. glauconiveus) | Unknown source, A. Blochwitz | EF652058 | EF651905 | EF651993 | EF651943 |

| NRRL 128 | Unknown source, G. Smith | EF652059 | EF651906 | EF651994 | EF651944 | |

| NRRL 136 | Unknown source, G. Smith | EF652062 | EF651909 | EF651995 | EF651945 | |

| NRRL 137 | Unknown source | EF652063 | EF651910 | EF651996 | EF651946 | |

| CCF 4191 = DTO 355-C1 | Spain, Andalusia, Málaga, Cueva del Tesoro, cave sediment from the cave wall, 2010, A. Nováková | HE801344 | HE801332 | HE974438 | HE974427 | |

| CCM F-530 = CCF 4038 | Czech Republic, garlic, L. Marvanová | HE578069 | HE578086 | HE578092 | HE578114 | |

| EMSL No. 2211 = CCF 5380 = DTO 355-H8 | USA, Montana, Great Falls, air of bathroom, 2013, Ž. Jurjević | LT670956 | LT671112 | LT671113 | LT671114 | |

| IHEM 1811 = DTO 355-C3 | Belgium, Namur, indoor air, 1983 | LT670957 | LT671115 | LT671116 | LT671117 | |

| CBS 101750 = CGMCC 3.04665 (AS 3.4665) = DTO 197-B4 (ex-type of A. parviverruculosus) | China, Hebei, soil | HE615135 | HE801331 | HE801323 | HE801312 | |

| CCF 4787 = KACC 47144 = DTO 355-C4 | South Korea, soybeans, 2012, D.H. Kim | LT670958 | LT671118 | LT671119 | LT671120 | |

| CCF 4790 = KACC 47147 = DTO 355-C5 | South Korea, soybeans, 2012, D.H. Kim | LT670959 | LT671121 | LT671122 | LT671123 | |

| CGMCC 3.06092 = DTO 348-F3 | China, Guangdong, cashew Kernel, 2001 | LT670960 | LT671124 | LT671125 | LT671126 | |

| A. osmophilus | CBS 134258T = IRAN 2090C = DTO 354-C1 | Iran, East Azerbaijan province, Marand, Triticum aestivum leaf, 2006, B. Asgari | KC473921 | LT671127 | LT671128 | LT671129 |

| A. porosus | CBS 141770T = DTO 262-D7 = IBT 34443 | Turkey, soil, 2013, A. Yoltas | LT670961 | LT671130 | LT671131 | LT671132 |

| DTO 308-D1 | Turkey, soil, 2014, R. Demirel | LT670962 | LT671133 | LT671134 | LT671135 | |

| CBS 375.75 = DTO 197-C4 | Israel, Arachis hypogaea fruit, P. Blaser | LT670963 | LT671136 | LT671137 | LT671138 | |

| DTO 262-D4 | Turkey, soil, 2013, A. Yoltas | LT670964 | LT671139 | LT671140 | LT671141 | |

| DTO 262-D2 | Turkey, soil, 2013, A. Yoltas | LT670965 | LT671142 | LT671143 | LT671144 | |

| A. proliferans | CBS 121.45T = NRRL 1908 = IBT 6213 = IMI 016105ii = IMI 016105iii = IMI 16105 = LSHB BB.82 = MUCL 15625 = NCTC 6546 = QM 7462 = UC 4303 = WB 1908 = CCF 5580 | UK, Manchester, cotton yarn, G. Smith | EF652064 | EF651891 | EF651988 | EF651941 |

| DTO 322-A2 | The Netherlands, egg waffles, 2014, M. Meijer | LT670966 | LT671145 | LT671146 | LT671147 | |

| CCF 4192 = DTO 355-C6 | Spain, Andalusia, Aracena, Gruta de la Maravillas, cave sediment, 2010, A. Nováková | HE615128 | HE801328 | HE801316 | HE801305 | |

| NRRL 114 = DTO 355-C7 = CCF 5579 | USA, Massachusetts, unknown source | EF652051 | EF651886 | EF651987 | EF651933 | |

| CCF 4096 = NRRL 62482 = DTO 355-C8 | Czech Republic, Prague, palm skin, 28-year-old woman, 2008, M. Skořepová | FR848827 | FR775375 | HE650908 | HE801303 | |

| CCF 4115 = NRRL 62497 = DTO 355-C9 | Czech Republic, Prague, toenail of 64-year-old man, 2010, P. Lysková | FR851850 | FR851855 | HE578090 | HE578107 | |

| CCF 4146 = NRRL 62494 = DTO 355-D1 | Czech Republic, Prague, toenail of 48-year-old man, 2011, P. Lysková | HE578067 | HE578076 | HE650909 | HE801304 | |

| NRRL 71 = DTO 355-D2 = CCF 5578 | USA, Maryland, leafhoppers, V.K. Charles | EF652047 | EF651885 | EF651986 | EF651932 | |

| CCF 4232 | Czech Republic, Opava, stuffed bird, 2010, M. Polásek | HE615129 | HE801329 | HE801317 | HE801306 | |

| EMSL No. 2207 = CCF 5395 = DTO 355-H5 | USA, Pennsylvania, Yardley, air of living room, 2013, Ž. Jurjević | LT670967 | LT671148 | LT671149 | LT671150 | |

| EMSL No. 2791 = CCF 5392 = DTO 355-H6 | USA, New York, Troy, basement, settle plates, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670968 | LT671151 | LT671152 | LT671153 | |

| CCF 4789 = KACC 47146 = DTO 355-D3 | South Korea, soybeans, 2012, D.H. Kim | LT670969 | LT671154 | LT671155 | LT671156 | |

| A. pseudoglaucus | CBS 123.28T = NRRL 40 = ATCC 10066 = IBT 5353 = IMI 016122 = IMI 016122ii = LSHBA 19 = MUCL 15624 = QM 7463 = Thom 5343 = WB 40 (lectotype of A. glaucoaffinis) | Unknown source, 1929, A. Blochwitz | EF652050 | EF651917 | EF652007 | EF651952 |

| NRRL 13 = CBS 529.65 (ex-type of A. reptans) | France, Prunus domestica, da Fonseca | EF652048 | EF651915 | EF652005 | EF651950 | |

| NRRL 17 | USA, wrist skin | EF652049 | EF651916 | EF652006 | EF651951 | |

| NRRL 25865 | Japan, Tokyo, unknown source, T. Ohtsuki | EF652065 | EF651918 | EF652008 | EF651953 | |

| CBS 101747 = CGMCC 3.04674 (AS 3.4674) (ex-type of A. fimicola) | China, Tibet, animal dung | HE615130 | HE801335 | HE801321 | HE801310 | |

| CBS 379.75 (ex-type of A. glaber) | Switzerland, Zuoz, Vaccinium myrtillus leaf, P. Blaser | HE615131 | HE801336 | HE801322 | HE801311 | |

| CCF 3283 | Czech Republic, Prague, 2002, A. Kubátová | FR727114 | FR775360 | HE974439 | HE578110 | |

| CCF 4011 | Czech Republic, Prague, back skin of 39-year-old woman, 2008, M. Skořepová | FR839678 | FR775358 | FR751446 | HE578111 | |

| EMSL No. 1780 = CCF 5388 = DTO 355-I2 | USA, Pennsylvania, floor swab, 2012, Ž. Jurjević | LT670970 | LT671157 | LT671158 | LT671159 | |

| EMSL No. 2779 = CCF 5389 = DTO 355-I3 | USA, Florida, Melbourne, vent, settle plates, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670971 | LT671160 | LT671161 | LT671162 | |

| EMSL No. 2809 = CCF 5386 | USA, New York, Endicott, office, settle plates, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670972 | LT671163 | LT671164 | LT671165 | |

| EMSL No. 2474 = CCF 5387 = DTO 355-I4 | USA, New Jersey, Piscataway, air, basement, 2014, Ž. Jurjević | LT670973 | LT671166 | LT671167 | LT671168 | |

| EMSL No. 2853 = CCF 5390 = DTO 355-I5 | USA, Missouri, St. Louis, cheddar cheese, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT670974 | LT671169 | LT671170 | LT671171 | |

| CBS 108961 = DTO 351-D2 | The Netherlands, Woerden, parmezan cheese, J. Houbraken | LT670975 | LT671172 | LT671173 | LT671174 | |

| DTO 147-G3 | Hungary, indoor air, 2010 | LT670976 | LT671175 | LT671176 | LT671177 | |

| CGMCC 3.00460 = DTO 348-B9 | China, tea, 1952 | LT670977 | LT671178 | LT671179 | LT671180 | |

| A. ruber | CBS 530.65T = NRRL 52 = ATCC 16441 = IBT 5453 = IMI 211380 = JCM 22942 = QM 1973 = Thom 5599B = WB 52 | Unknown source | EF652066 | EF651920 | EF652009 | EF651947 |

| NRRL 76 | Unknown source, G. Smith | EF652067 | EF651921 | EF652011 | EF651948 | |

| NRRL 5000 = CBS 464.65 (ex-type of A. athecius) | UK, coffee beans, 1965, E. Yuill | EF652080 | EF651922 | EF652010 | EF651949 | |

| CBS 101748 = CGMCC 3.04632 (AS 3.4632) (ex-type of A. tuberculatus) | China, Shanxi, soil | HE615134 | HE801337 | HE801325 | HE801315 | |

| CCF 2920 | Czech Republic, Nymburk, malt dust, 1993, A. Kubátová | FR727112 | FR775357 | FR751444 | HE974430 | |

| CCF 4377 | Czech Republic, Prague, toenail of 60-year-old woman, 2011, P. Lysková | HE578065 | HE578087 | HE578098 | LT671190 | |

| CBS 104.18 = DTO 351-C4 | Unknown source, 1918, O. Goethals | LT670978 | LT671181 | LT671182 | LT671183 | |

| DTO 238-C4 | Unknown source, Rahmawati | LT670979 | LT671184 | LT671185 | LT671186 | |

| CGMCC 3.00457 = DTO 348-B6 | China, tea, 1952 | LT670980 | LT671187 | LT671188 | LT671189 | |

| A. sloanii | CBS 138177T = DTO 245-A1 = IBT 34509 = CCF 4927 | UK, Middlesex, house dust, 2010, E. Whitfield & K. Mwange | KJ775540 | KJ775074 | LT671038 | KX463365 |

| CBS 138176 = DTO 244-I8 = CCF 4926 | UK, Middlesex, house dust, 2010, E. Whitfield & K. Mwange | KJ775539 | KJ775073 | LT671039 | KX463364 | |

| CBS 138231 = DTO 245-A6 | UK, Middlesex, house dust, 2010, E. Whitfield & K. Mwange | KJ775541 | KJ775075 | KJ775311 | KX450899 | |

| CBS 138178 = DTO 245-A8 | UK, Middlesex, house dust, 2010, E. Whitfield & K. Mwange | KJ775542 | KJ775076 | KJ775313 | KX450900 | |

| CBS 138179 = DTO 245-A9 | UK, Middlesex, house dust, 2010, E. Whitfield & K. Mwange | KJ775543 | KJ775077 | KJ775314 | KX450901 | |

| A. tamarindosoli | CBS 141775T = DTO 054-A8 = IBT 34432 | Thailand, Hua Hin, soil under tamarind, 2007, R.A. Samson & J. Houbraken | LT670981 | LT671191 | LT671192 | LT671193 |

| A. teporis | CBS 141768T = DTO 058-E5 = IBT 34513 | The Netherlands, heat treated corn kernels, 2008, M. Meijer | LT670982 | LT671194 | LT671195 | LT671196 |

| A. tonophilus | CBS 405.65T = NRRL 5124 = ATCC 16440 = ATCC 36504 = IBT 21230 = IMI 108299 = QM 8599 = WB 5124 = CCF 5592 | Japan, Tokyo, binocular lens, T. Ohtsuki | EF652081 | EF651919 | EF652000 | EF651969 |

| DTO 356-H6 = KAS6175 | Canada, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie | LT670915 | LT671197 | LT671198 | LT671199 | |

| CCF 4785 = KACC 45365 = DTO 355-A2 | South Korea, meju, 2012, S.B. Hong | LT670984 | LT671200 | LT671201 | LT671202 | |

| CCF 4786 = KACC 47150 = DTO 355-A1 | South Korea, soybeans, 2012, D.H. Kim | LT670985 | LT671203 | LT671204 | LT671205 | |

| A. xerophilus | CBS 938.73T = NRRL 6131 = IBT 5429 = IBT 5489 = IBT 34503 = DTO 083-A2 = CCF 5593 | Egypt, Western desert, desert soil, J. Mouchacca | EF652085 | EF651923 | EF651983 | EF651970 |

| NRRL 6132 = CBS 755.74 | Egypt, Western desert, desert soil, J. Mouchacca | EF652086 | EF651924 | EF651984 | EF651971 | |

| A. zutongqii | CBS 141773T = CGMCC 3.13917 = DTO 349-E1 = IBT 34450 | China, Beijing, peanut shell, 2008, L. Wang | LT670986 | LT671206 | LT671207 | LT671208 |

| CGMCC 3.06103 = DTO 348-F7 | China, Ningxia, 2001 | LT670987 | LT671209 | LT671210 | LT671211 | |

| CGMCC 3.03980 = DTO 348-D7 | China, 1969, Z.T. Qi | LT670988 | LT671212 | LT671213 | LT671214 | |

| CGMCC 3.03961 = DTO 348-D5 | China, ocular lens, 1969, Z.T. Qi | LT670989 | LT671215 | LT671216 | LT671217 | |

Culture collection designations: CBS, Culture Collection of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands; CGMCC, China General Microbiological Culture Collection Centre, Beijing, China; NRRL, Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, Peoria, Illinois, USA; KACC, Korean Agricultural Culture Collection, Wanju, South Korea; CCF, Culture Collection of Fungi, Prague, Czech Republic; CCM (F-), Czech Collection of Microorganisms, Brno, Czech Republic; IBT, culture collection of the DTU Systems Biology, Lyngby, Denmark; DAOMC, Canadian Collection of Fungal Cultures, at the Ottawa Research and Development Centre – Agriculture and Agri-Food, Ottawa, Canada; BCCM/IHEM, Belgian Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms; DTO, working collection of the Applied and Industrial Mycology department (DTO) housed at the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute.

For newly isolated strains from the indoor environments, different isolation techniques were used. House dust samples were collected as described in Amend et al. (2010) and isolated using a modified dilution-to-extinction method (Visagie et al. 2014a). Air samples were collected approximately 1 m above the ground with a viable impaction sampler (MAS 100 Merck) (Peterson & Jurjević 2013). Indoor surfaces (walls, ceilings) were sampled with the swab (Greiner Bio-One, Alphen aan de Rijn, the Netherlands). For air and swab sampling, standard microbiological techniques were used for isolation. Malt extract agar (MEA) with chloramphenicol and Dichloran 18 % glycerol agar (DG18) were used as isolation media.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

Strains were grown for 1 wk on M40Y prior to DNA extraction. DNA was extracted using the Ultraclean™ Microbial DNA isolation Kit (MoBio, Solana Beach, U.S.A.) or the ArchivePure DNA yeast and Gram2+ kit (5 PRIME Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) according to manufacturer instructions updated by Hubka et al. (2015). Target loci, i.e. ITS, BenA, CaM and RPB2, were amplified using primer combination listed in Table 2. PCR product purification followed the protocol described by Réblová et al. (2016). Automated sequencing was performed at the Macrogen Sequencing Service (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) using same primers used in PCR.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study for amplification and sequencing.

| Locus | Primer | Amplification | Annealing temp (°C) | Cycles | Orientation | Sequence (from 5′ to 3′) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | V9G (General, Gen.) | Standard | 55 (alt. 52) | 35 | Forward | TTACGTCCCTGCCCTTTGTA | de Hoog & Gerrits van den Ende (1998) |

| LS266 (Gen.) | Reverse | GCATTCCCAAACAACTCGACTC | Masclaux et al. (1995) | ||||

| ITS1 (Alternative, Alt.) | Forward | TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG | White et al. (1990) | ||||

| ITS4 (Alt.) | Reverse | TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC | White et al. (1990) | ||||

| BenA | Bt2a (Gen.) | Standard | 55 (alt. 52) | 35 | Forward | GGTAACCAAATCGGTGCTGCTTTC | Glass & Donaldson (1995) |

| Bt2b (Gen.) | Reverse | ACCCTCAGTGTAGTGACCCTTGGC | Glass & Donaldson (1995) | ||||

| T10 (Alt.) | Forward | ACGATAGGTTCACCTCCAGAC | O'Donnell & Cigelnik (1997) | ||||

| Ben2F (Alt.) | Forward | TCCAGACTGGTCAGTGTGTAA | Hubka & Kolařík (2012) | ||||

| CaM | CMD5 (Gen.) | Standard | 55 (alt. 52) | 35 | Forward | CCGAGTACAAGGAGGCCTTC | Hong et al. (2005) |

| CMD6 (Gen.) | Reverse | TTTYTGCATCATRAGYTGGAC | Hong et al. (2005) | ||||

| CF1L (Alt.) | Forward | GCCGACTCTTTGACYGARGAR | Peterson (2008) | ||||

| CF1M (Alt.) | Forward | AGGCCGAYTCTYTGACYGA | Peterson (2008) | ||||

| CF4 (Alt.) | Reverse | TTTYTGCATCATRAGYTGGAC | Peterson (2008) | ||||

| RPB2 | fRPB2-5F (Gen.) | Standard | 55 (alt. 52 or 50) | 35 | Forward | GAYGAYMGWGATCAYTTYGG | Liu et al. (1999) |

| fRPB2-7CR (Gen.) | Reverse | CCCATRGCTTGYTTRCCCAT | Liu et al. (1999) | ||||

| fRPB2ResF100 (Alt.) | Touch-up | 44-46-48 | 5-5-30 | Forward | TGAARTAYGCICTTGCYAC | Sklenář et al. (2017) | |

| fRPB2ResR950 (Alt.) | Reverse | CARTGYGTCCADGTRTGKGC | Sklenář et al. (2017) | ||||

| RPB2-F50-CanAre (Alt.) | Touch-down | 65-64-63-62-61-60-55 | 1-1-1-1-1-1-38 | Forward | TTGAACATTGGTGTCAAGGC | Jurjević et al. (2015) |

Phylogenetic analysis

Sequences were inspected and assembled in BioEdit v.7.1.8 (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html). Sequence alignments were performed using the FFT-NSi strategy implemented in MAFFT v.7 (Katoh & Standley 2013). Alignment characteristics are listed in Table 3. Maximum likelihood (ML) trees were constructed with IQ-TREE v. 1.4.0 (Nguyen et al. 2015). Optimal partitioning scheme and substitution models were selected using PartitionFinder v1.1.0 (Lanfear et al. 2012) with setting allowing introns, exons and codon positions to be independent datasets. The Bayesian information criterion was used to determine the model that best fits the data. Proposed partitioning schemes and substitution models for each dataset are listed in Table 4. Support values at branches were obtained from 1 000 bootstrap replicates. The trees were rooted with Hamigera avellanea NRRL 1938. MrBayes 3.2.2 (Ronquist et al. 2012) was used to calculate Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP). Optimal partitioning scheme and substitution models were selected using PartitionFinder v1.1.0 as described above. The analyses ran for 107 generations, two parallel runs with four chains each were used, every 1 000th tree was retained, and the first 25 % of trees were discarded as burn-in. All alignments are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.7hn1j.

Table 3.

Overview of alignments characteristics used for phylogenetic analyses (excluding outgroup).

| ITS | BenA | CaM | RPB2 | BenA + CaM + RPB2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (bp) | 538 | 402 | 710 | 969 | 2 081 |

| Variable position | 76 | 164 | 284 | 286 | 734 |

| Parsimony informative sites | 52 | 149 | 251 | 243 | 643 |

Table 4.

Partition-merging results and best substitution model for each partition according to Bayesian information criterion (BIC) as proposed by PartitionFinder v1.1.0.

| Dataset | Phylogenetic method | Partitioning scheme (substitution model) |

|---|---|---|

| ITS | ML | ITS1 + ITS2 (HKY+G); 5.8S (JC+I) |

| BI | ITS1 + ITS2 (HKY+G); 5.8S (JC+I) | |

| BenA | ML | introns (K80+G); 1st codon positions (JC+I); 2nd codon positions (JC); 3rd codon positions (K81uf+G) |

| BI | introns (K80+G); 1st codon positions (JC+I); 2nd codon positions (JC); 3rd codon positions (HKY+G) | |

| CaM | ML | introns (HKY+I+G); 1st codon positions (TrN+I); 2nd codon positions (F81); 3rd codon positions (TrN+G) |

| BI | introns (HKY+I+G); 1st codon positions (HKY+I); 2nd codon positions (F81); 3rd codon positions (GTR+G) | |

| RPB2 | ML | 1st codon positions (TrN+I+G); 2nd codon positions (JC+I); 3rd codon positions (TrNef+G) |

| BI | 1st + 2nd codon positions (K80+I+G); 3rd codon positions (HKY+G) | |

| BenA + CaM + RPB2 | ML | BenA + CaM introns (K81uf+I+G); 1st codon positions of BenA + CaM + RPB2 (TrN+I+G); 2nd codon positions of BenA + CaM + RPB2 (F81+I); 3rd codon positions of BenA + CaM (GTR+G); 3rd codon positions of RPB2 (TrNef+G) |

| BI | BenA + CaM introns (HKY+I+G); 1st codon positions of BenA + CaM + RPB2 (GTR+I+G); 2nd codon positions of BenA + CaM + RPB2 (F81+I); 3rd codon positions of BenA + CaM (GTR+G); 3rd codon positions of RPB2 (HKY+G) |

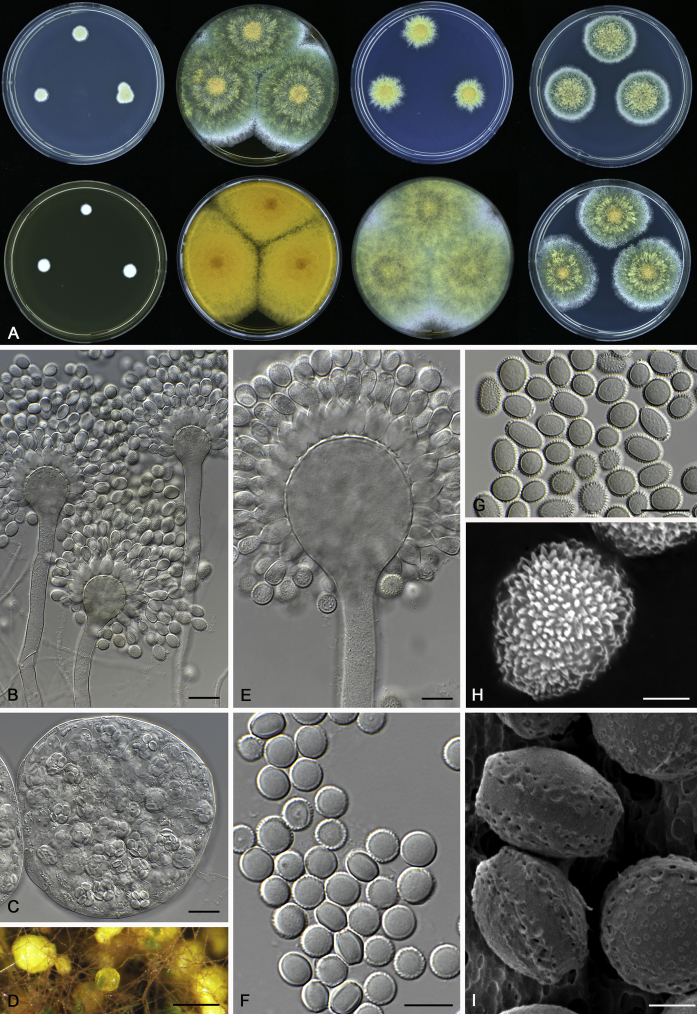

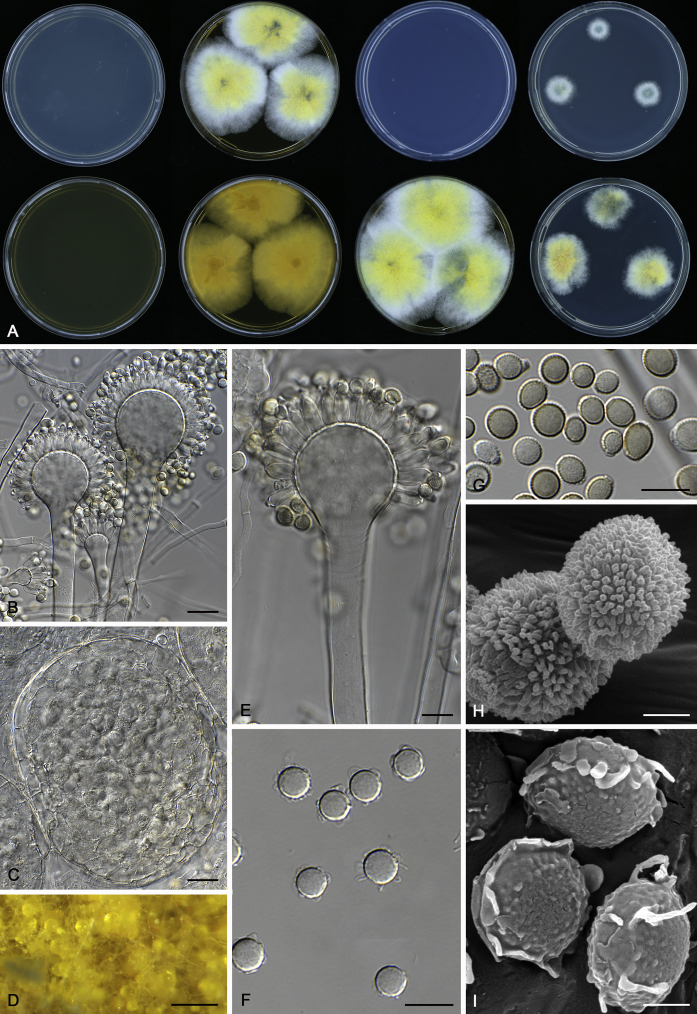

Morphological analysis

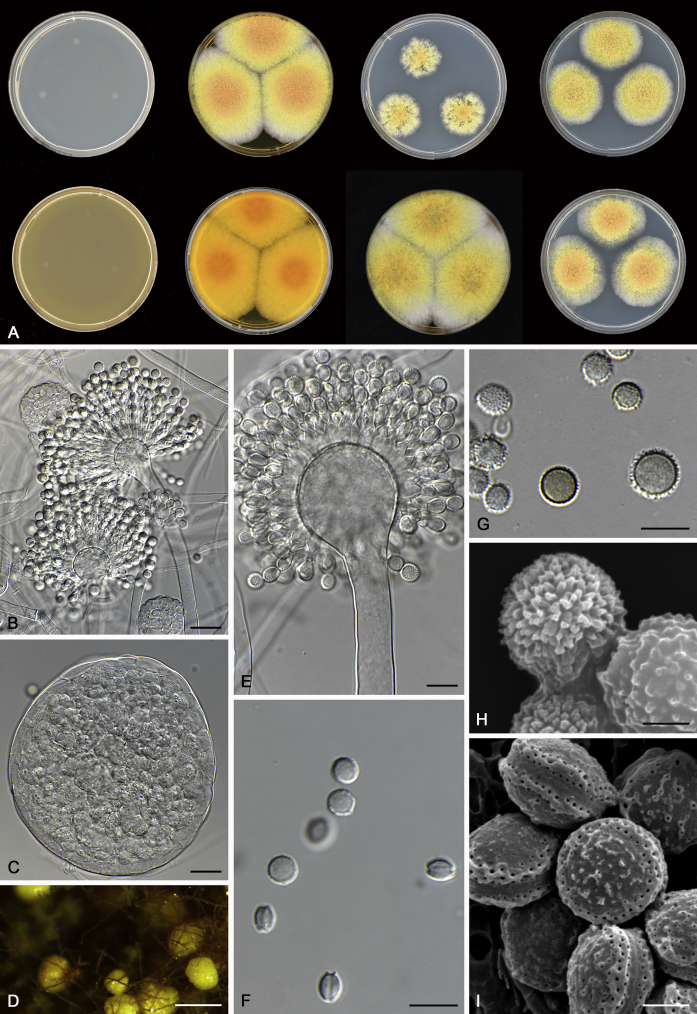

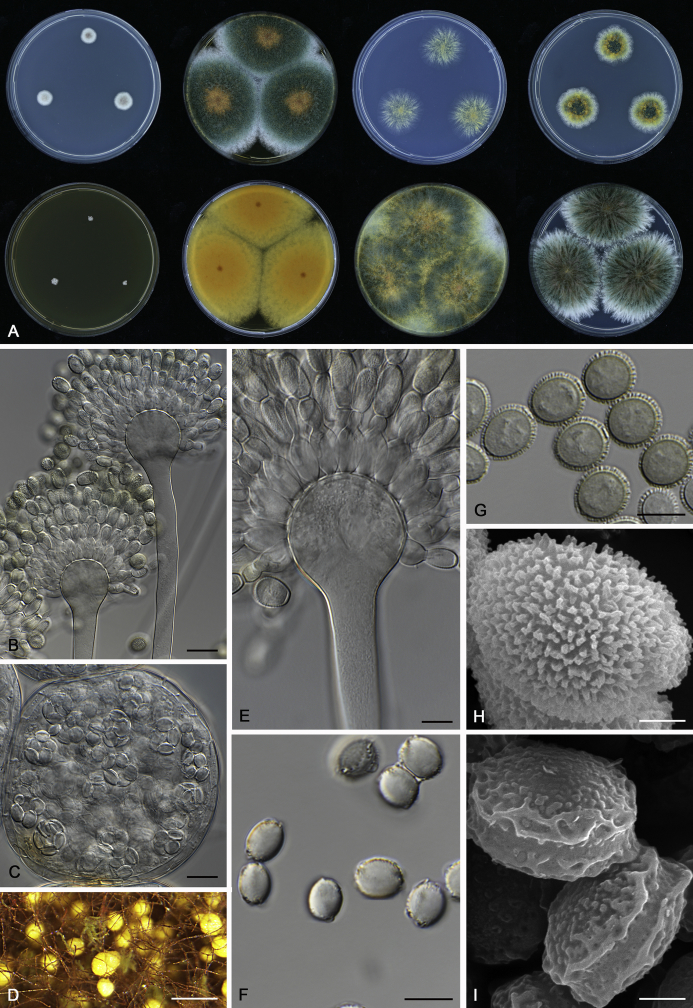

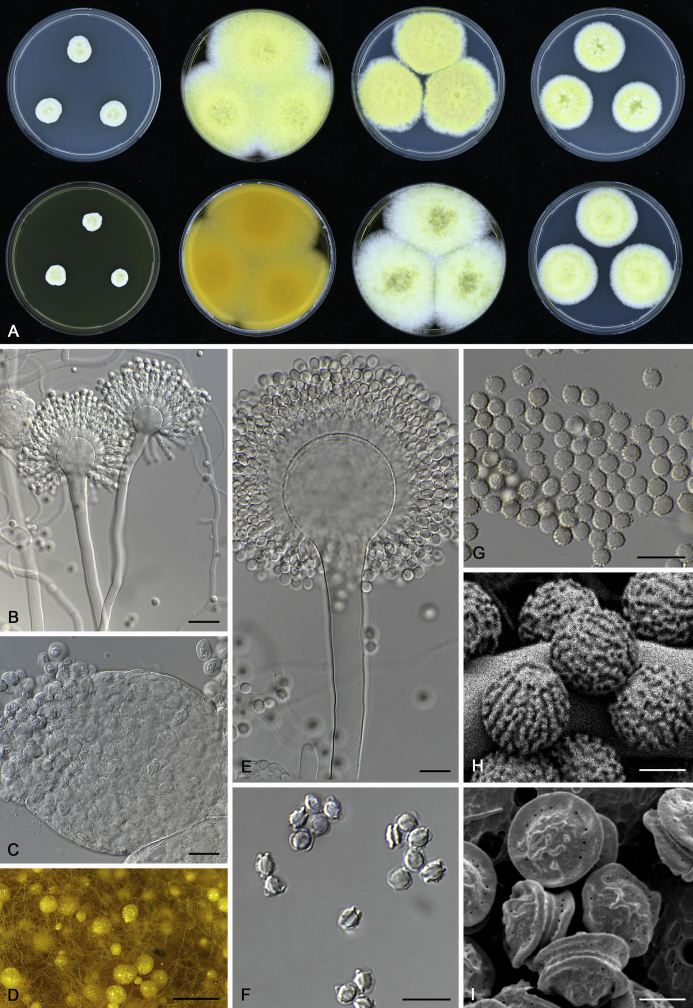

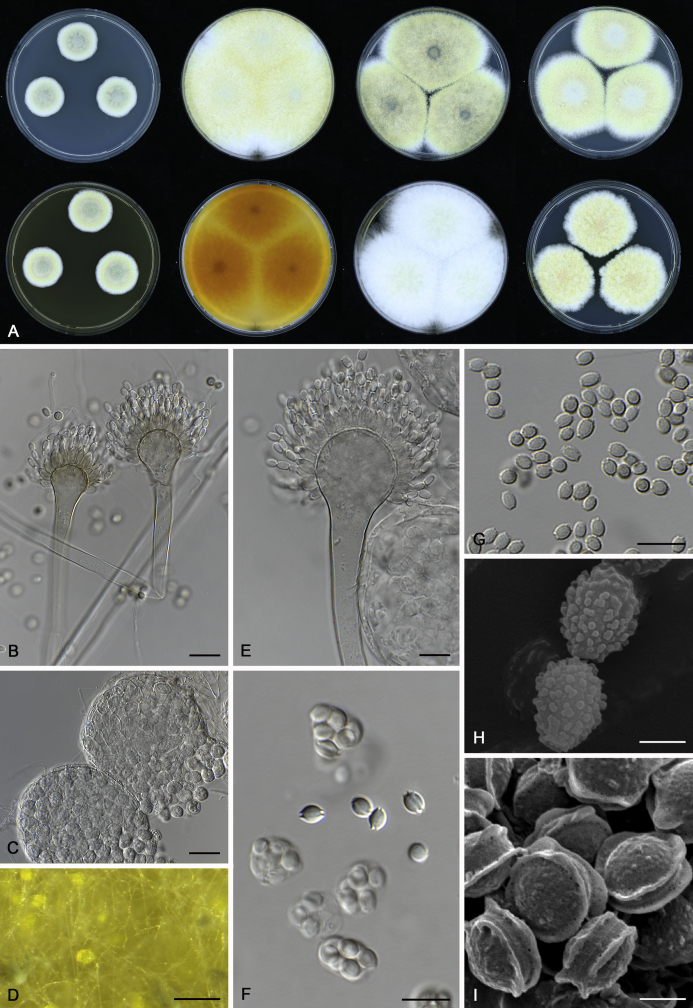

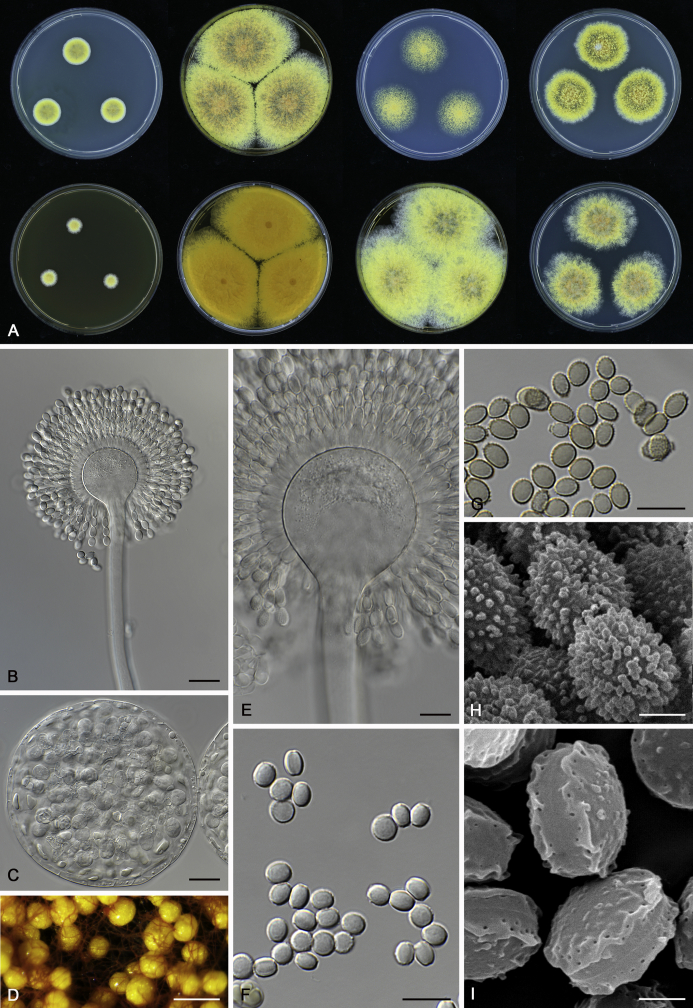

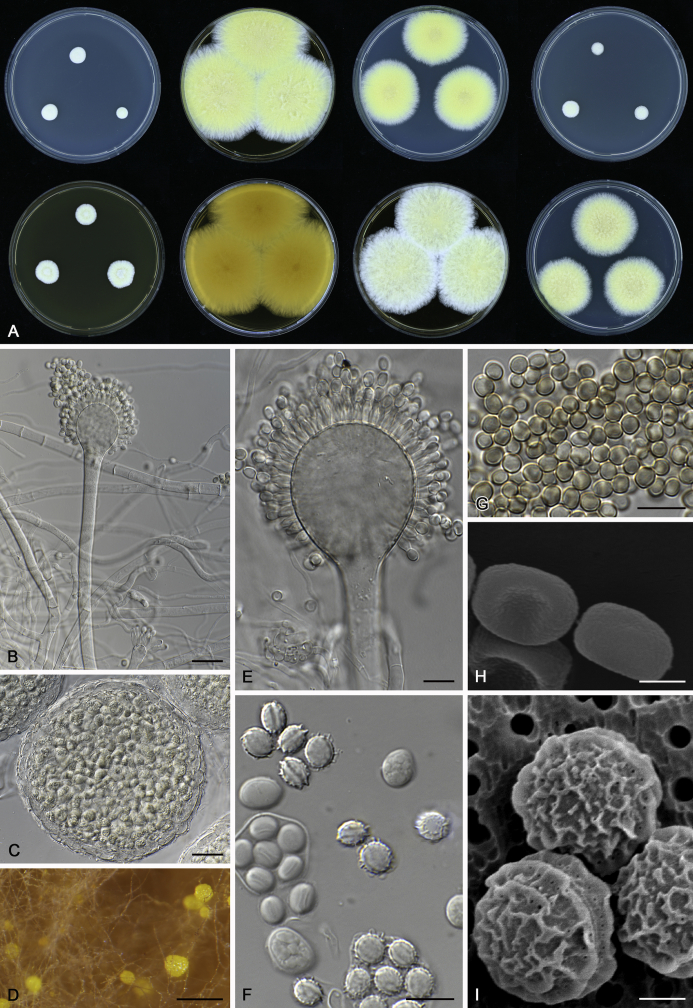

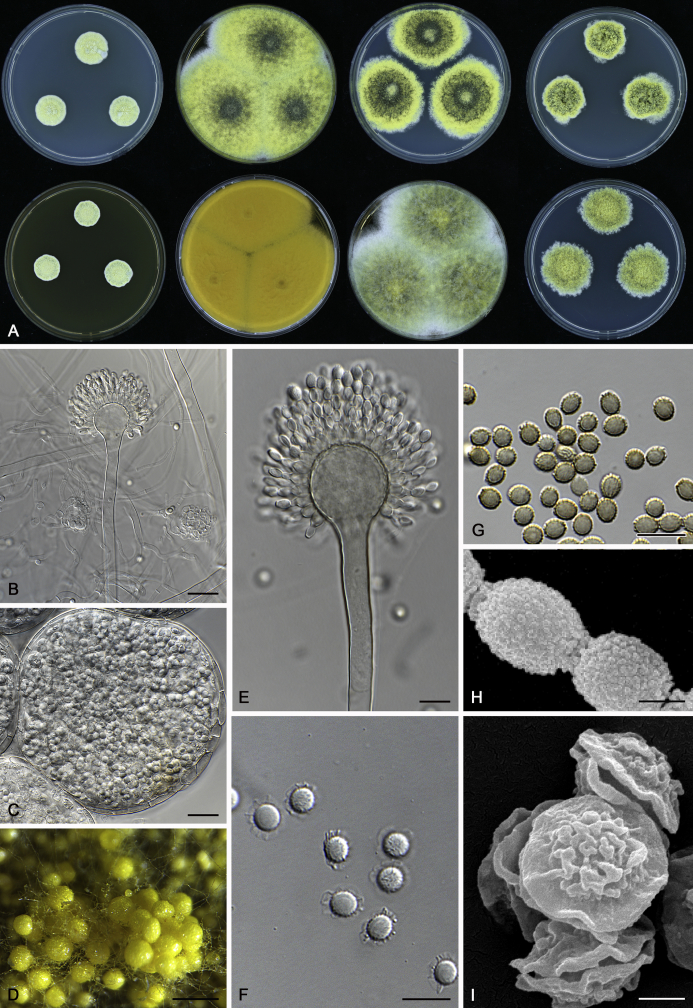

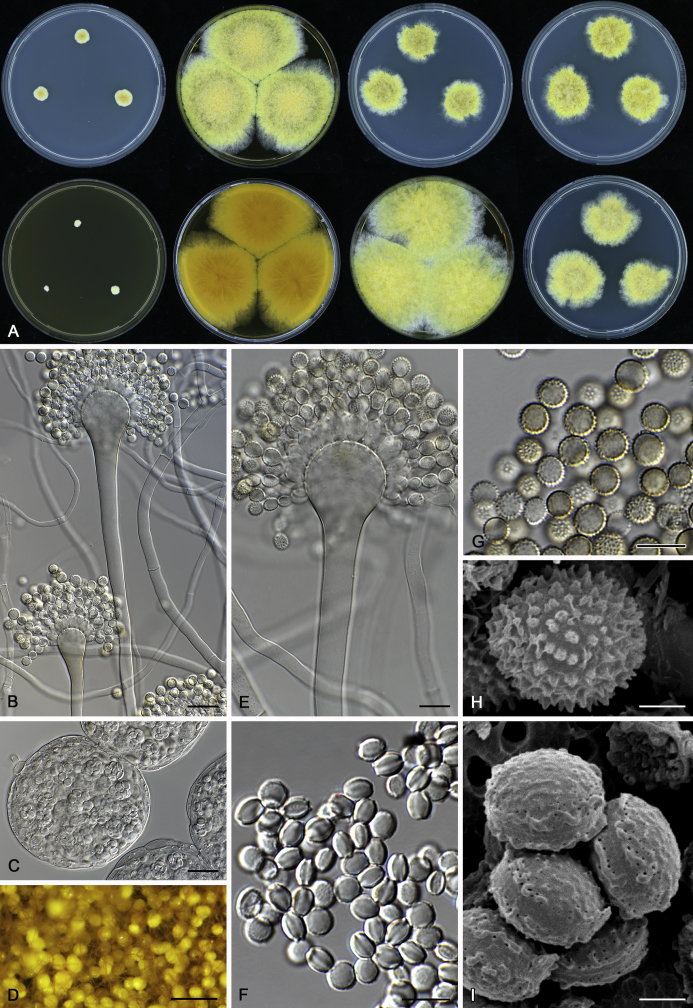

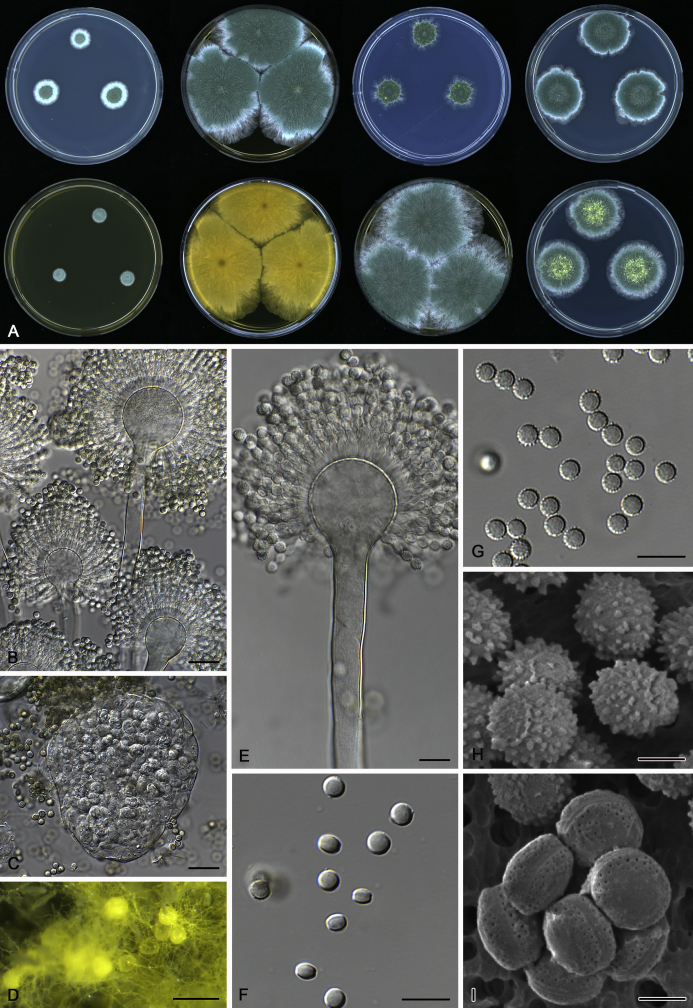

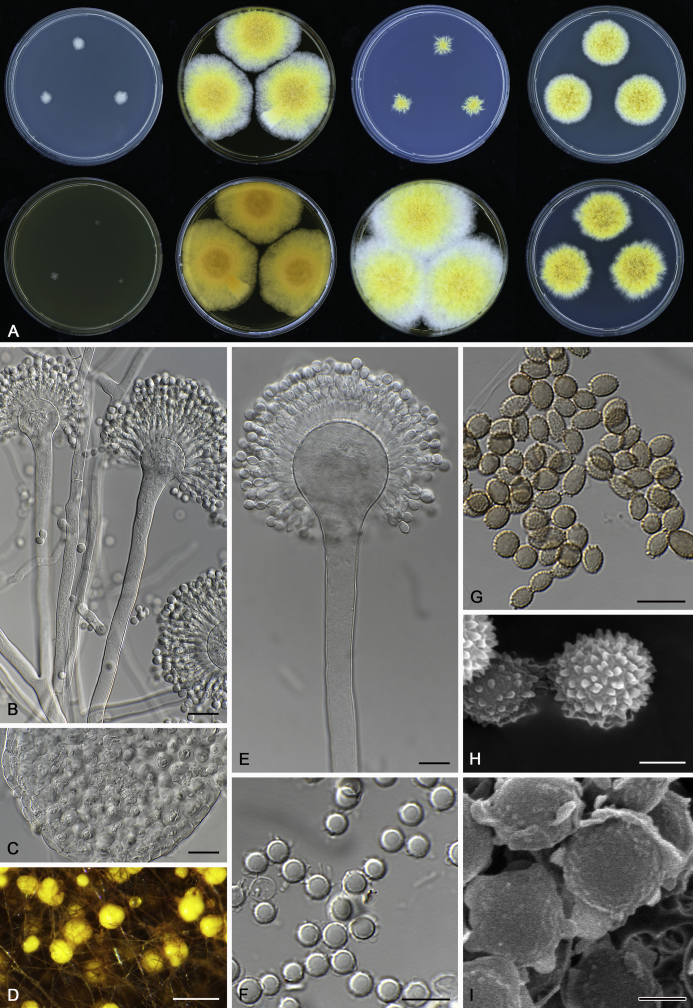

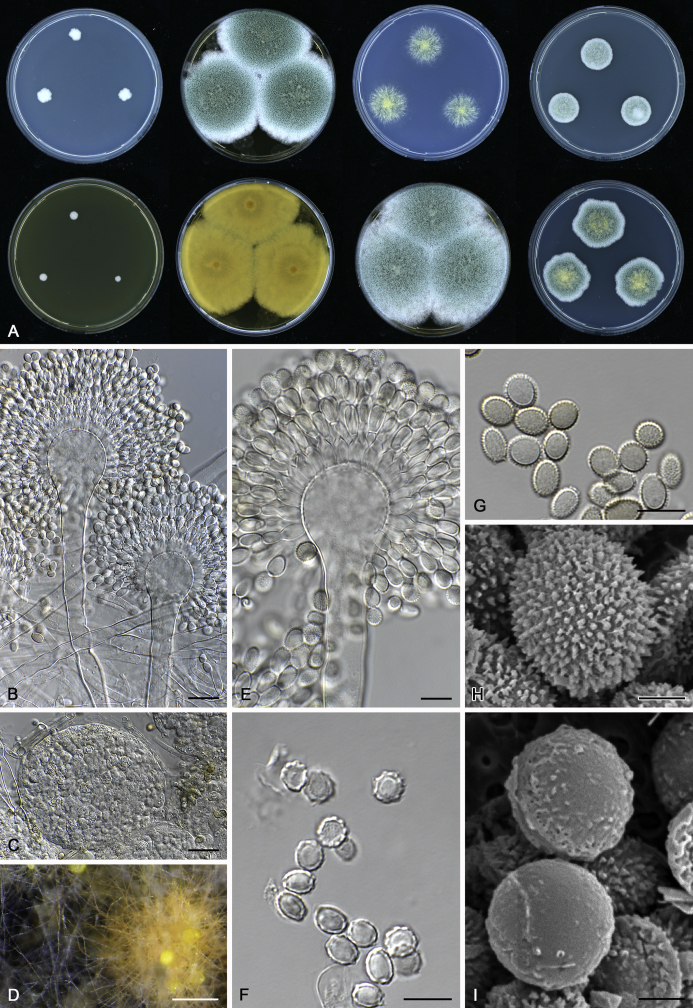

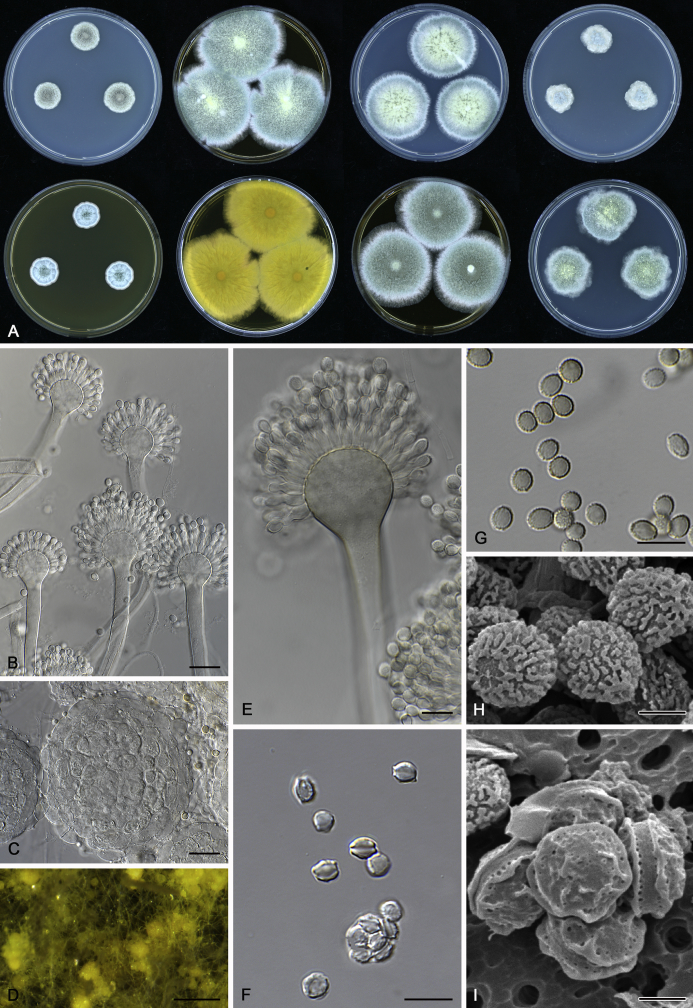

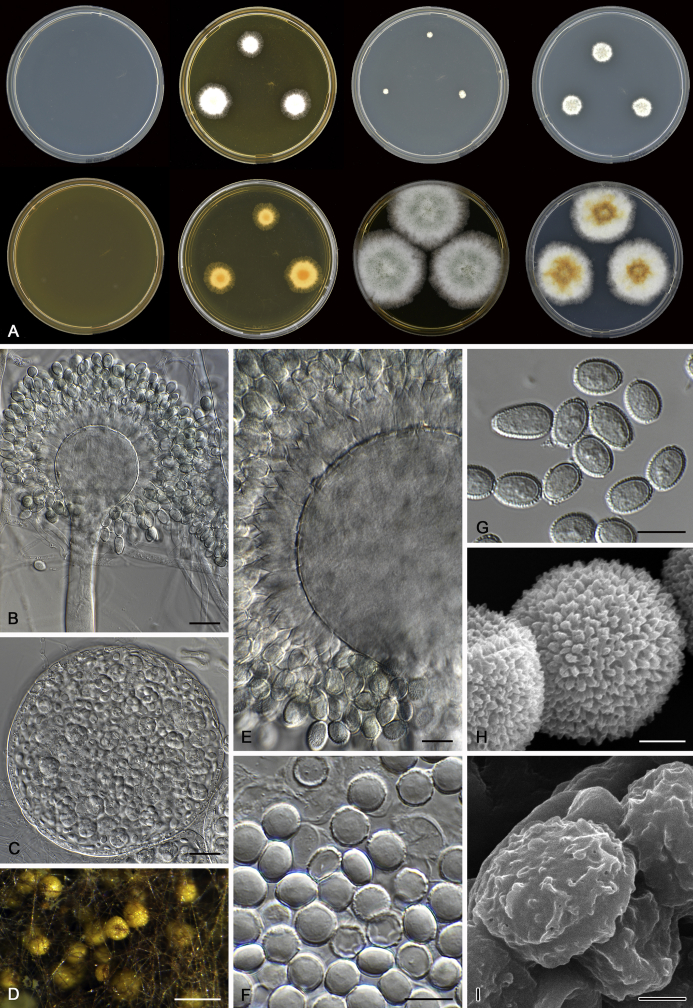

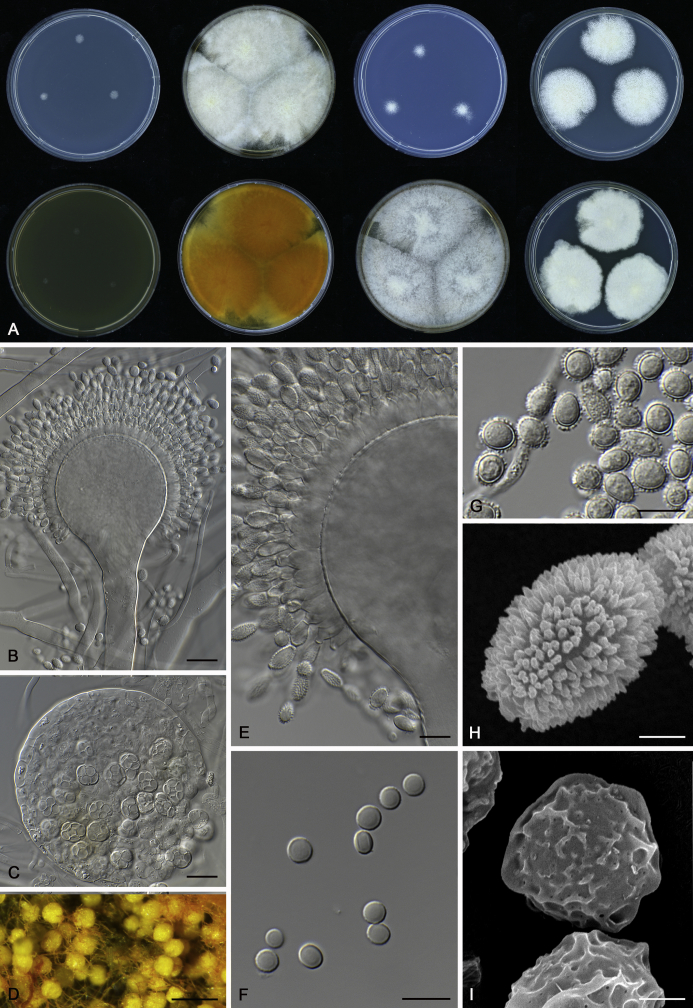

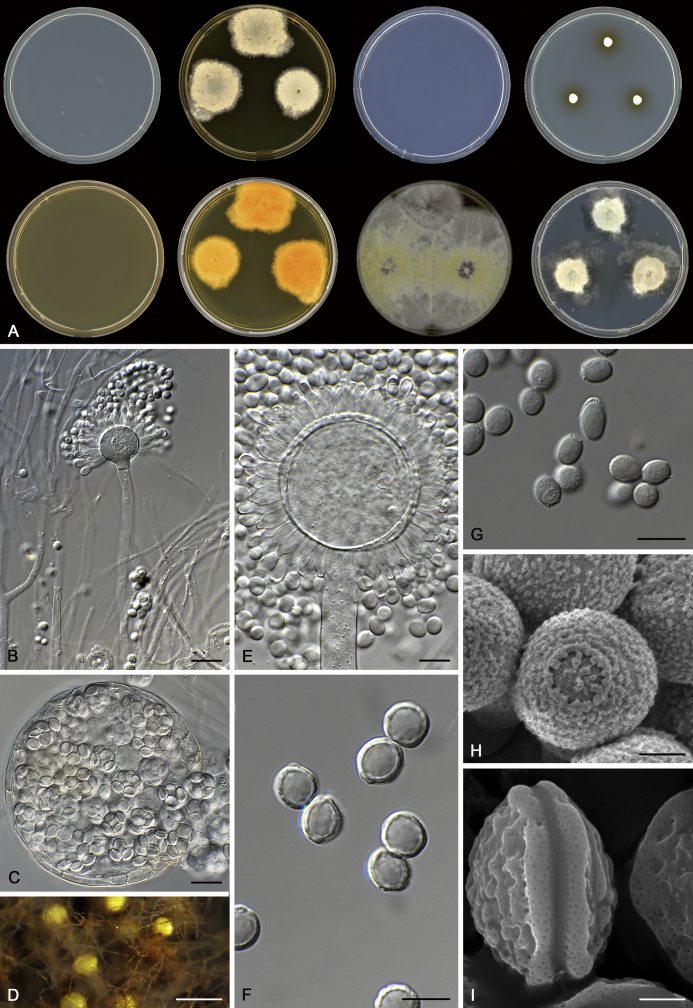

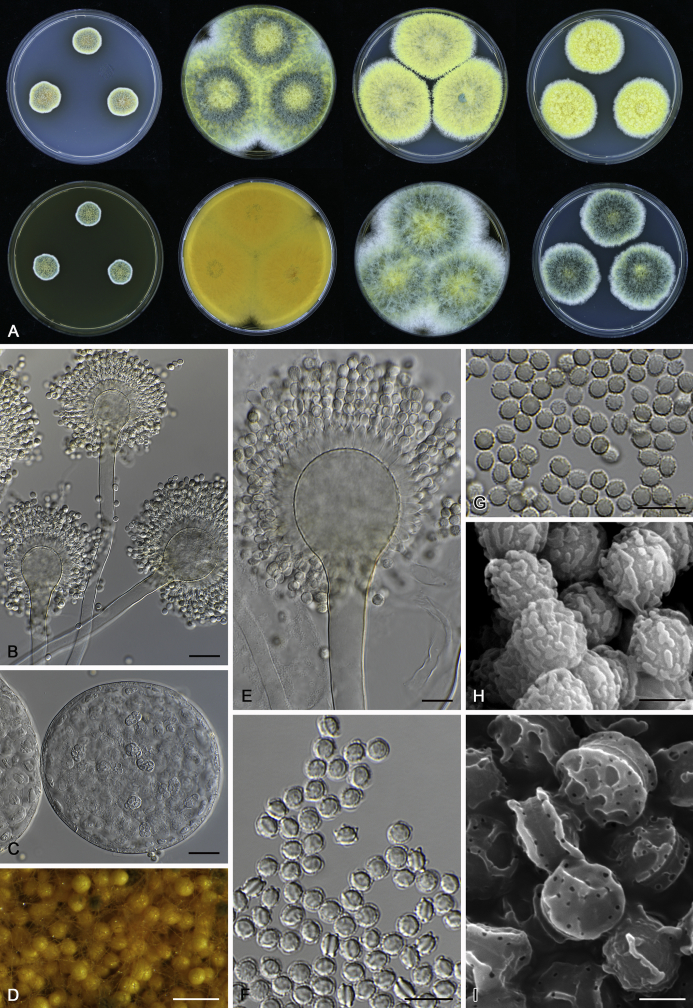

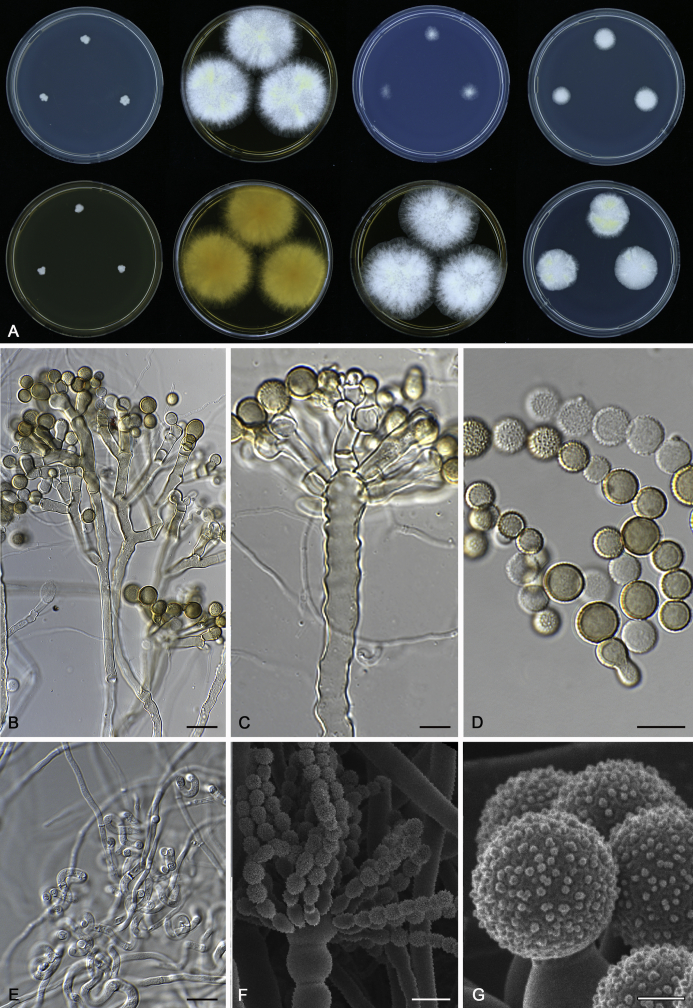

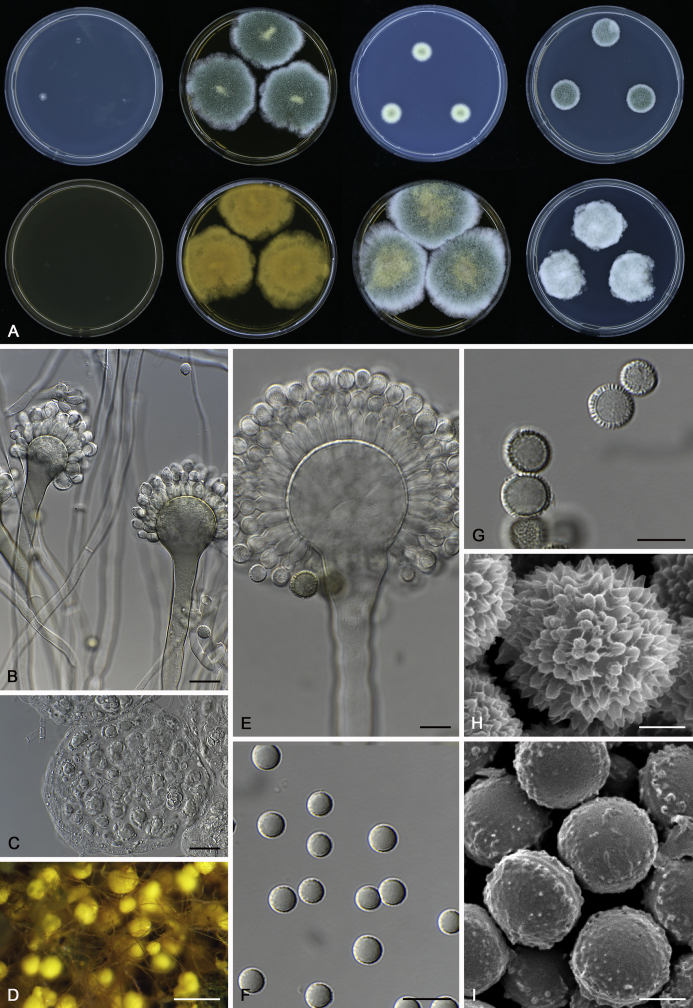

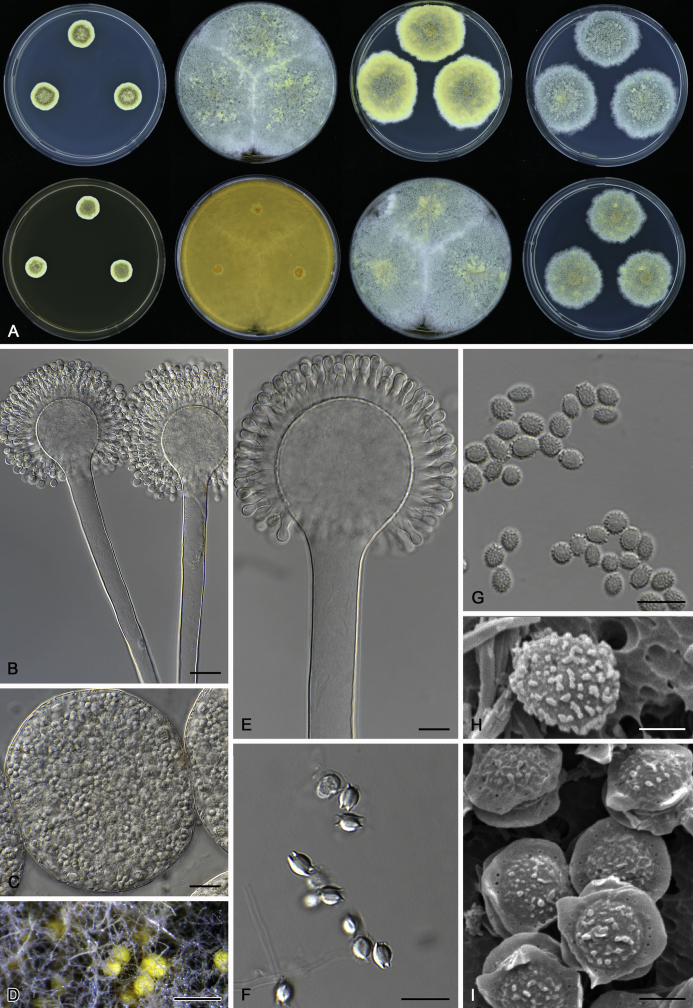

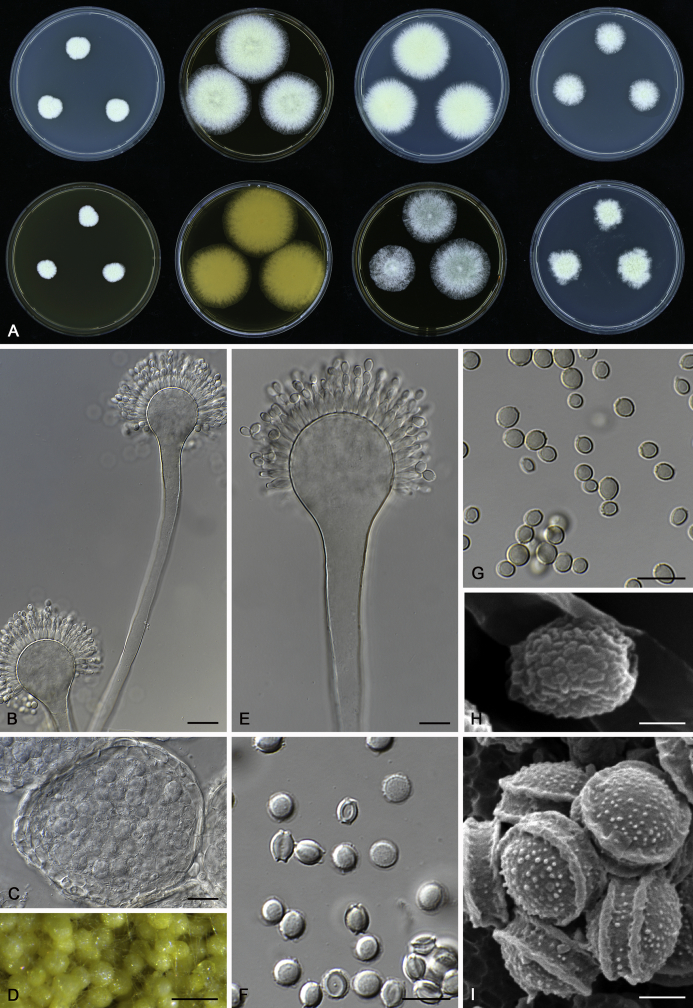

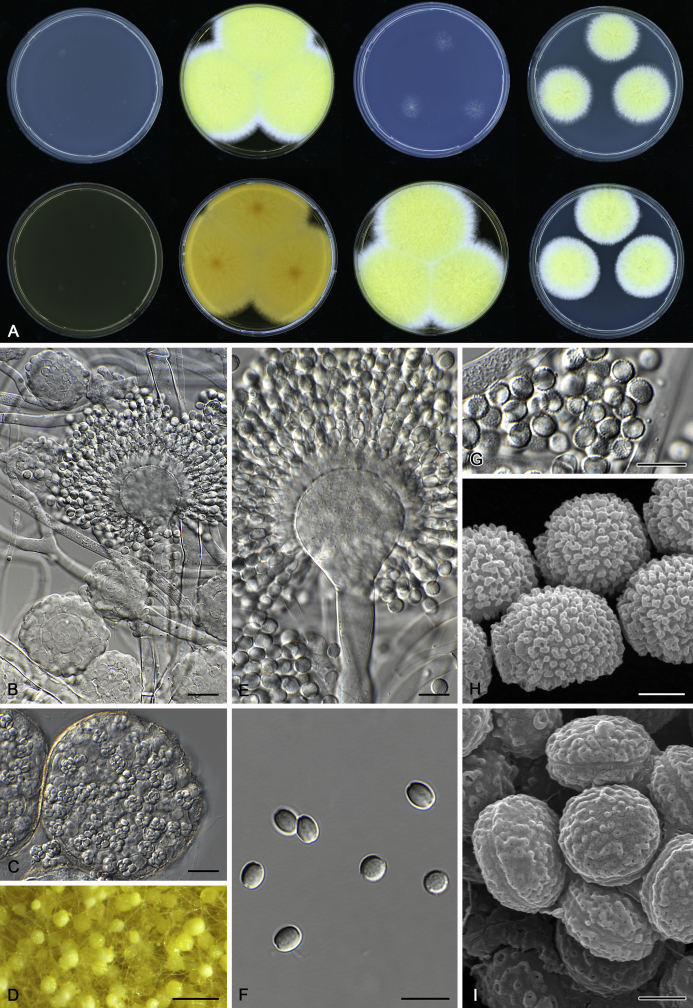

Macroscopic characters were studied on agar media Czapek yeast autolysate agar (CYA), CYA with 20 % sucrose agar (CY20S), CYA supplemented with 5 % NaCl (CYAS), Malt extract agar (MEA; Oxoid), MEA with 40 % sucrose agar (M40Y), MEA with 60 % sucrose agar (M60Y), MEA supplemented with 10 % NaCl (MEA10S) and Dichloran 18 % glycerol agar (DG18). Trace elements (0.1 g ZnSO4·7H2O and 0.5 g CuSO4·5H2O in 100 ml distilled water) were added to all media to obtain stable pigment production and consistent conidial colours (Smith, 1949, Samson et al., 2014). Isolates were inoculated at three points on 90 mm plates and incubated for 7 d at 25 °C in darkness. In addition, CY20S and M60Y plates were incubated at 30 °C and 37 °C, respectively. After 7 d of incubation, colony diameters were recorded. Colony texture, degree of sporulation, obverse and reverse colony colours, production of soluble pigments, exudates and ascomata were determined. Colour codes used in description refer to Rayner (1970).

Light microscope preparations were made from 1 wk old colonies grown on M40Y. Ascomata, asci and ascospores were observed after 2 or 4 wks. Lactic acid (60 %) was used as mounting fluid. Ethanol (96 %) was used to remove excess conidia and prevent air bubbles. A Zeiss Stereo Discovery V20 dissecting microscope and Zeiss AX10 Imager A2 light microscope both equipped with Nikon DS-Ri2 cameras and NIS-Elements D v 4.50 software were used to capture digital images.

Cryo Scanning Electron Microscopy (cryo-SEM) observations of ascospores were prepared based on Chen et al. (2016), alternatively, an osmium tetroxide method was used for fixation as described by Hubka et al. (2013b). To prevent conidia collapsing, agar blocks containing conidial structures were snap-frozen and observed as described in Visagie et al. (2013).

Extrolite analysis

Strains were incubated on DG18, CY20S and YES for 7 d at 25 °C in darkness. Two agar plugs (diameter 6 mm) were subsequently cut out from each medium and placed in an Eppendorf plastic vial and extracted with ethyl acetate / isopropanol (75:25, vol/vol) with 1 % formic acid. After ultrasonication for 50 mins the extraction liquid was transferred to another Eppendorf vial and the organic solvents evaporated. The chemical content was re-dissolved in 400 μl methanol and centrifuged at 13 400 rpm for 3 min. One μl liquid was injected into a HPLC-DAD with an additional fluorescence detector as described by Nielsen et al. (2011). For fluorescence detection, the excitation wavelength was 230 nm and the emission wavelengths were 333 nm and 450 nm. This allowed for sensitive detection of ochratoxins, aflatoxins, citrinin and indol alkaloids. Alkylphenone retention indices were calculated according to Frisvad and Thrane, 1987, Frisvad and Thrane, 1993.

Results and discussion

Phylogeny

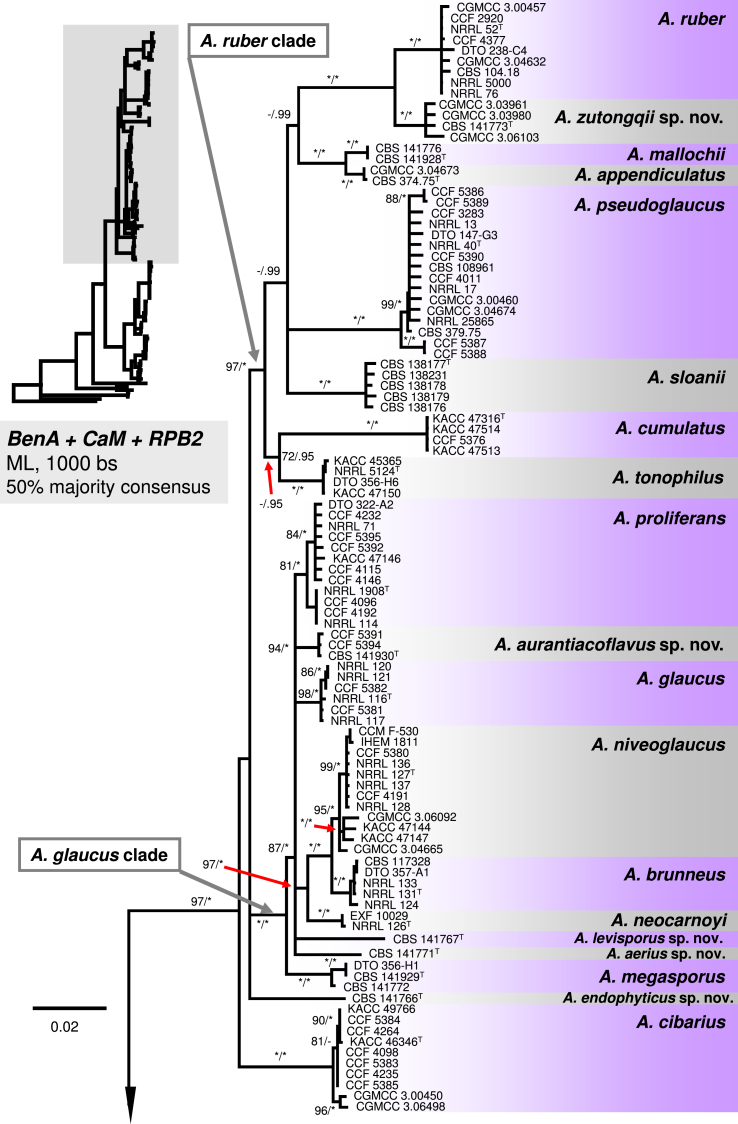

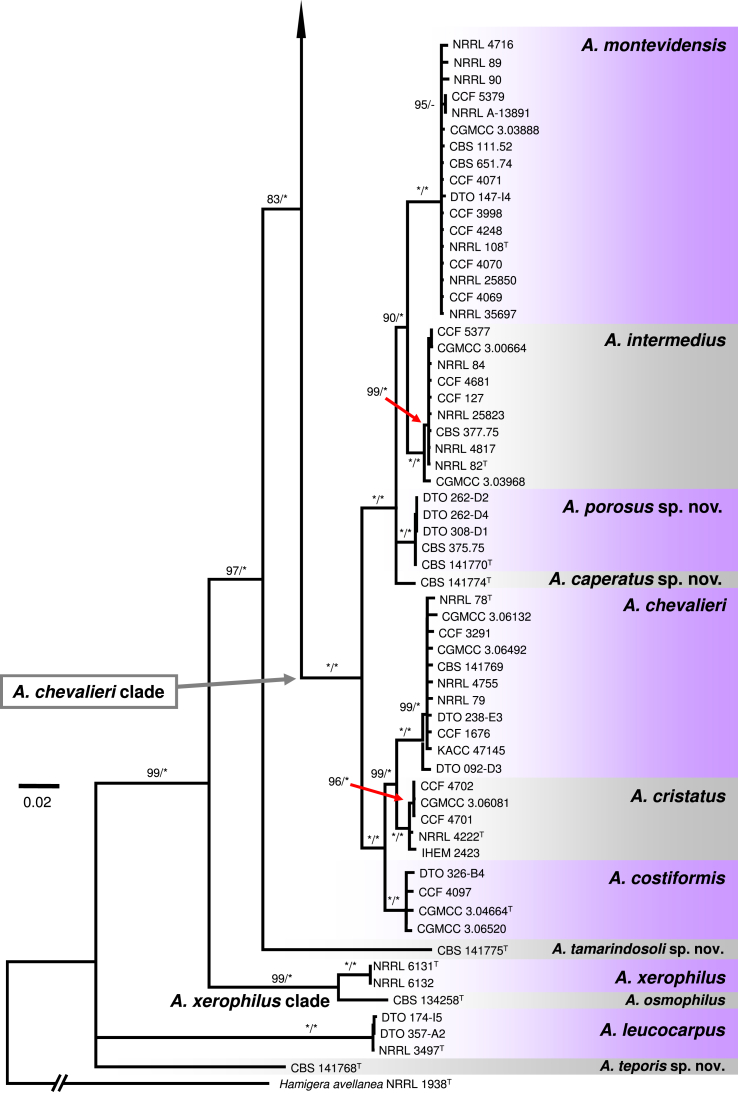

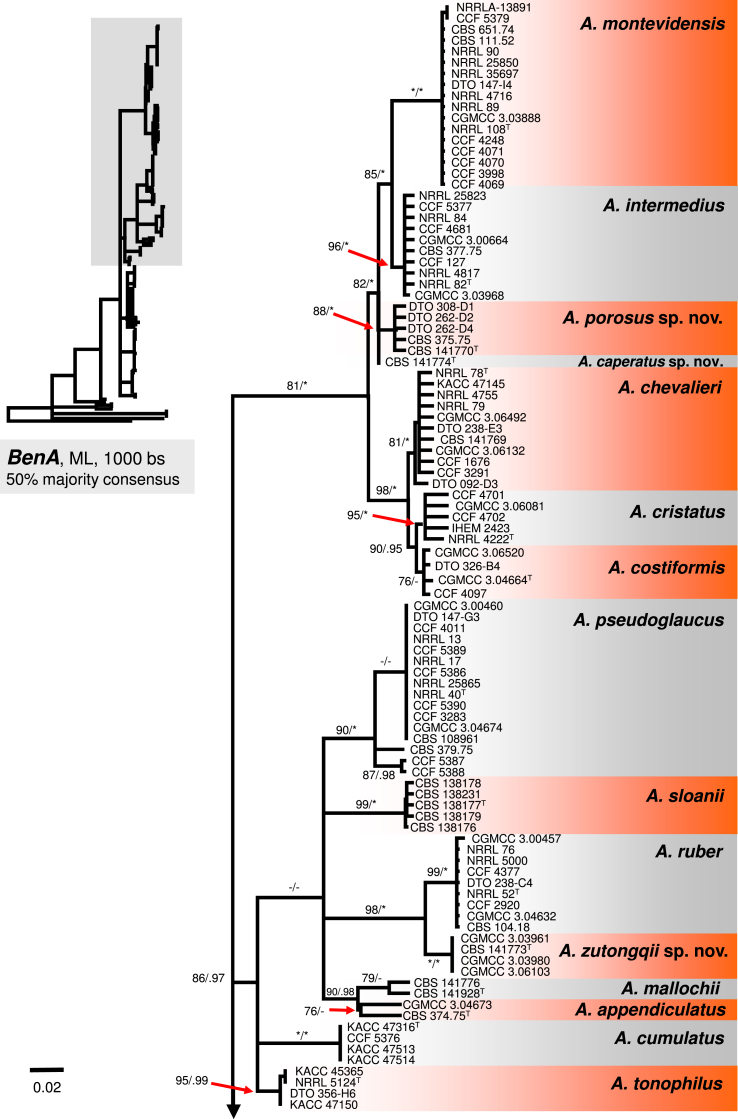

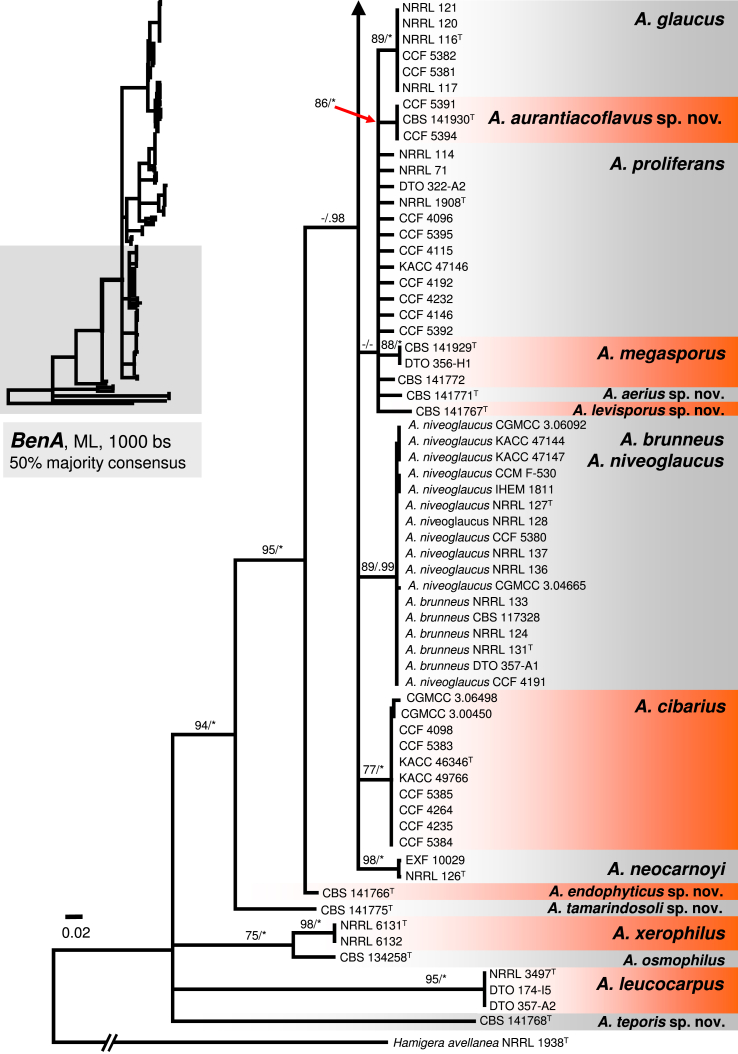

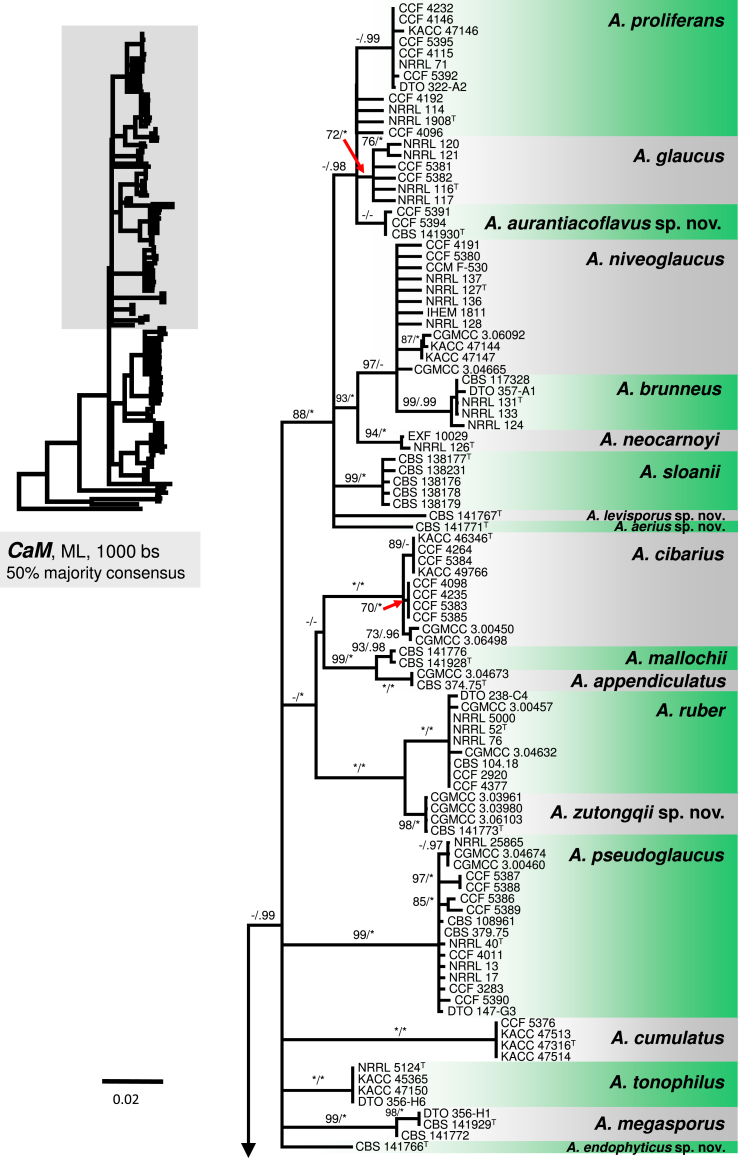

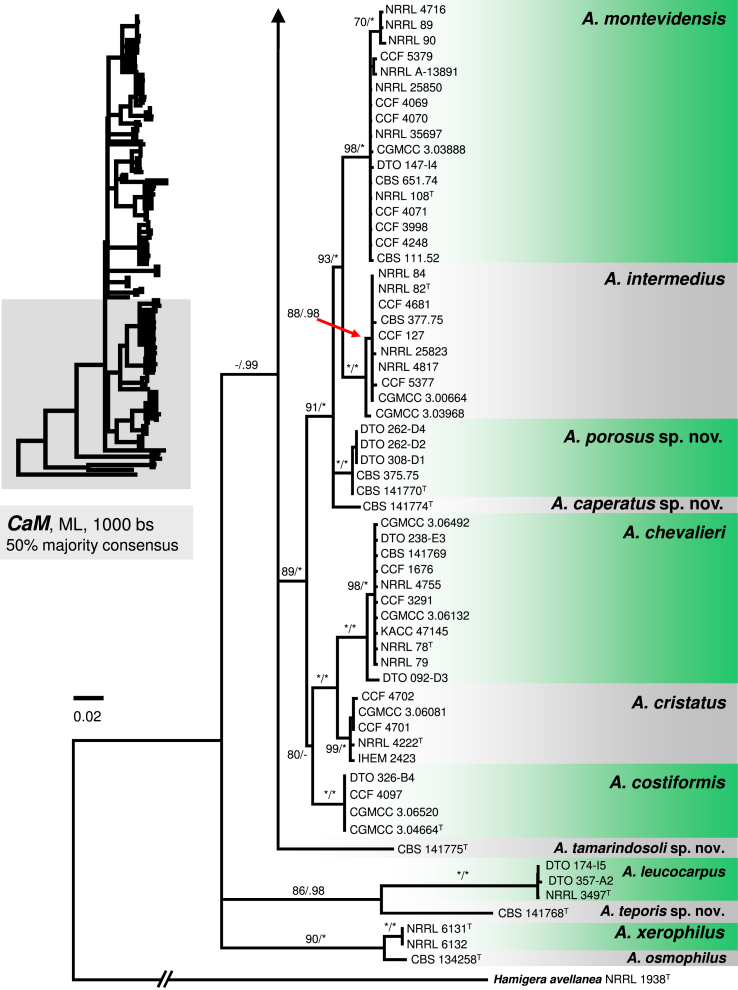

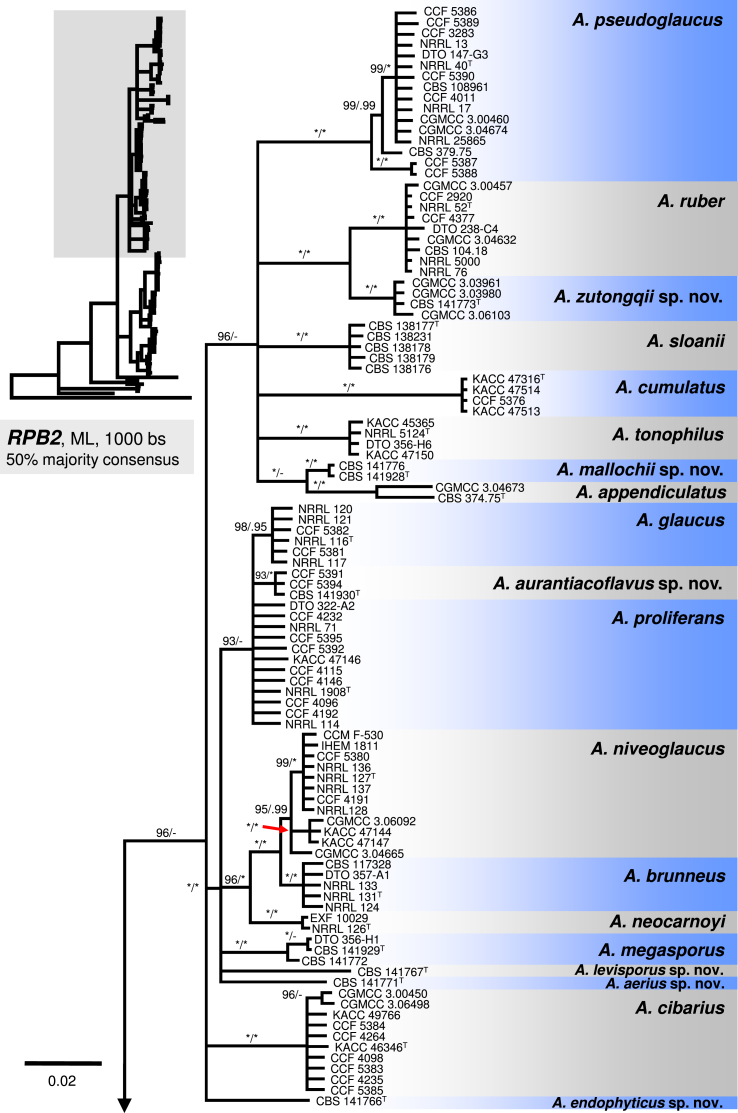

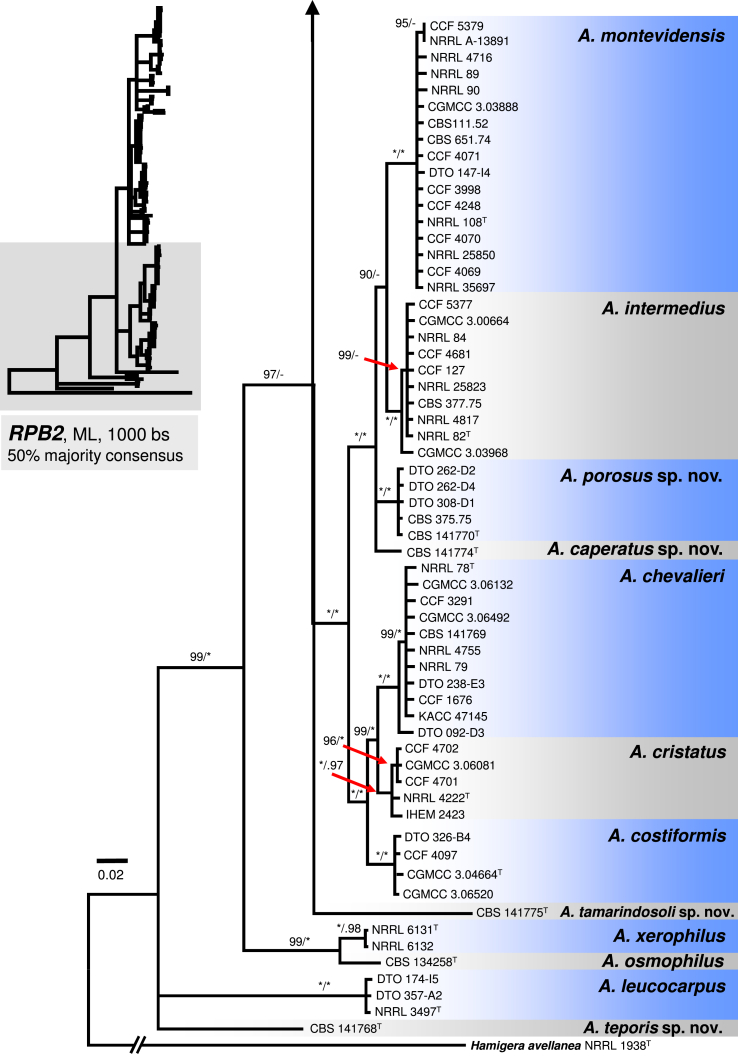

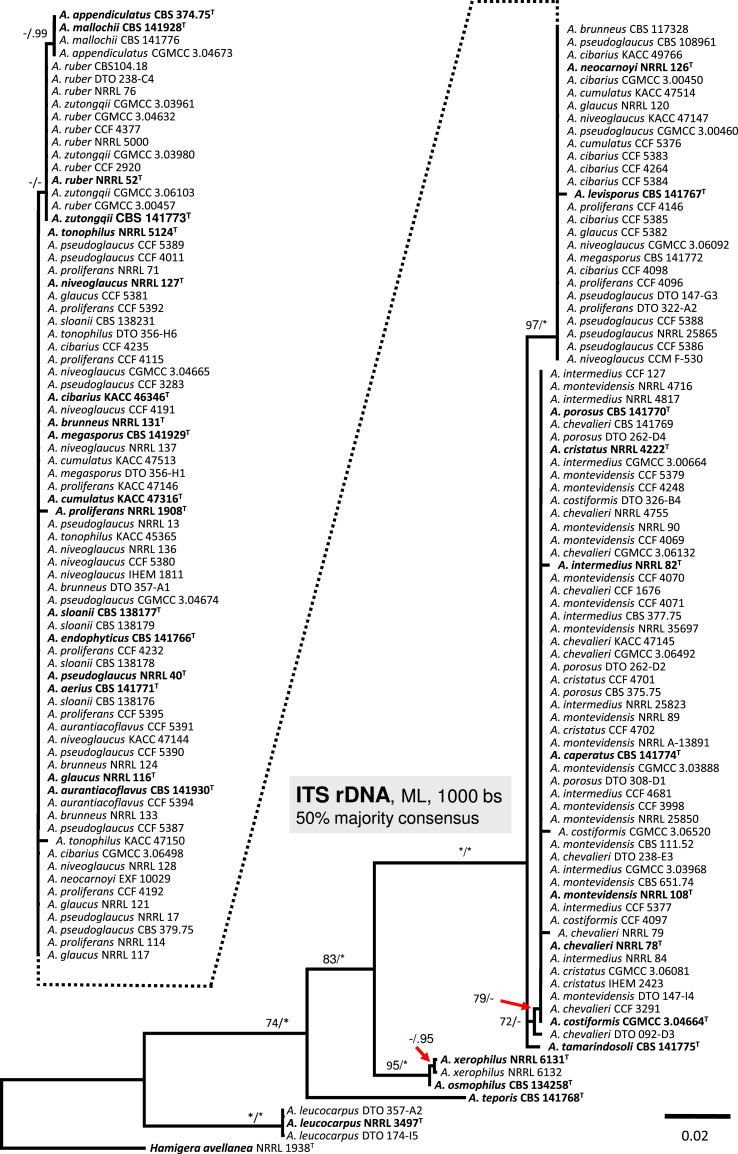

The phylogenetic relationships between 163 sect. Aspergillus strains were studied using concatenated sequence data of three loci: BenA, CaM and RPB2. In the 50 % majority consensus ML tree shown in Fig. 1, members of sect. Aspergillus are resolved in three major clades (named here the A. ruber, A. glaucus and A. chevalieri clades) and several, mostly basal, lineages containing one or two species. The Bayesian consensus tree was nearly identical to ML and therefore Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) are shown on the ML tree nodes.

Fig. 1.

A 50 % majority rule Maximum likelihood consensus tree based on combined dataset of BenA, CaM and RPB2 sequences showing the relationship of species within Aspergillus sect. Aspergillus. Dataset contained 164 taxa, other alignment characteristics, partitioning scheme and nucleotide substitution models are listed in Table 3, Table 4. Maximum likelihood bootstrap proportion (bs) and Bayesian posterior probability (pp) are appended to nodes; only bs ≥ 70 % and pp ≥ 95 % are shown, lower supports are indicated with a hyphen, whereas asterisks indicate full support (100 % bs or 1.00 pp); ex-type strains are designated by a superscript T. The tree is rooted with Hamigera avellanea NRRL 1938T.

The A. ruber clade contains A. appendiculatus, A. cumulatus, A. mallochii, A. pseudoglaucus, A. ruber, A. sloanii, A. tonophilus, and a new species A. zutongqii, with four strains originating from China (CBS 141773, CGMCC 3.03961, CGMCC 3.03980, CGMCC 3.06103) forming a sister clade to A. ruber. Its placement as sister to A. ruber is further supported by the single-gene trees (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Aspergillus fimicola (ex-type: CBS 101747), Aspergillus glaber (ex-type: CBS 379.75) and A. reptans (ex-type: NRRL 13) resolve in the A. pseudoglaucus lineage; A. tuberculatus (ex-type: CBS 101748) and A. athecius (ex-type: NRRL 5000) in the A. ruber lineage; and A. aridicola (ex-type: CBS 101746) in the A. appendiculatus lineage. Very similar topologies of the A. ruber clade was produced by phylogenetic analyses based on BenA (86 % BS / 0.97 PP; Fig. 2) and RPB2 (96 % BS / 0.79 PP; Fig. 4), while these topologies were not supported by CaM-based phylogeny (Fig. 3). All eight lineages within the clade were strongly supported in the combined phylogenetic analyses as well as single-gene analyses (BS ≥ 90 %, PP ≥ 0.98). The exception is in the BenA phylogeny where nodes bearing A. mallochii and A. appendiculatus had limited support (79 % BS / 0.92 PP and 76 % BS / 0.88 PP, respectively; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A 50 % majority rule Maximum likelihood consensus tree based on partial β-tubulin (BenA) sequences showing the relationship of species within Aspergillus sect. Aspergillus. Maximum likelihood bootstrap proportion (bs) and Bayesian posterior probability (pp) are appended to nodes; only bs ≥ 70 % and pp ≥ 95 % are shown, lower supports are indicated with a hyphen, whereas asterisks indicate full support (100 % bs or 1.00 pp); ex-type strains are designated by a superscript T. The tree is rooted with Hamigera avellanea NRRL 1938T.

Fig. 3.

A 50 % majority rule Maximum likelihood consensus tree based on partial calmodulin (CaM) sequences showing the relationship of species within Aspergillus sect. Aspergillus. Maximum likelihood bootstrap proportion (bs) and Bayesian posterior probability (pp) are appended to nodes; only bs ≥ 70 % and pp ≥ 95 % are shown, lower supports are indicated with a hyphen, whereas asterisks indicate full support (100 % bs or 1.00 pp); ex-type strains are designated by a superscript T. The tree is rooted with Hamigera avellanea NRRL 1938T.

Fig. 4.

A 50 % majority rule Maximum likelihood consensus tree based on partial RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPB2) sequences showing the relationship of species within Aspergillus sect. Aspergillus. Maximum likelihood bootstrap proportion (bs) and Bayesian posterior probability (pp) are appended to nodes; only bs ≥ 70 % and pp ≥ 95 % are shown, lower supports are indicated with a hyphen, whereas asterisks indicate full support (100 % bs or 1.00 pp); ex-type strains are designated by a superscript T. The tree is rooted with Hamigera avellanea NRRL 1938T.

The A. glaucus clade contains A. brunneus, A. glaucus, A. megasporus, A. niveoglaucus, A. neocarnoyi, A. proliferans and three new species (Fig. 1). Three isolates originating from the USA (CBS 141930, CCF 5391 and CCF 5394) formed a well-supported clade (94 % BS / 1.00 PP) closely related to A. glaucus and A. proliferans (Fig. 1); this clade showed moderate to high support in BenA and RPB2 phylogenies (Fig. 2, Fig. 4), but weak support in the CaM tree (Fig. 3). The clade is introduced as a new species, A. aurantiacoflavus, in the taxonomy section. All three species (A. glaucus, A. proliferans and A. aurantiacoflavus) have fixed single-nucleotide polymorphisms at BenA, CaM and RPB2 loci that guarantee their reliable discrimination from each other (positions in particular alignments available in Dryad Digital Repository — BenA: positions 53, 138, 219 and 297; CaM: positions 2, 131, 460, 600; RPB2: positions 211, 279, 666). CBS 141771 and CBS 141767 formed distinct single-isolate lineages nested in the A. glaucus clade but with unresolved position. They are distantly related to each other and remaining taxa in the clade based on CaM and RPB2 data, and are proposed below as new species A. aerius and A. levisporus. In the BenA phylogeny, these two species are resolved on a weakly supported branch with A. proliferans, A. glaucus, A. aurantiacoflavus and A. megasporus (Fig. 2), but their sequences contain numerous substitutions sufficient for reliable identification. Aspergillus medius (ex-type: NRRL 124) belongs in the A. brunneus lineage, A. parviverruculosus (ex-type: CBS 101750) in the A. niveoglaucus lineage, and A. manginii (ex-type: NRRL 117) and A. umbrosus (ex-type: NRRL 120) in the A. glaucus lineage. The A. proliferans lineage includes a strictly anamorphic ex-type strain NRRL 1908 and numerous isolates producing eurotium-like sexual state. Tree topologies of the A. glaucus clade in the CaM, RPB2 and combined trees are nearly identical (Fig. 1, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). In contrast, the BenA locus has only limited discriminatory power in this clade and many species were collapsed in a polytomy (Fig. 2). But still BenA sequences are sufficient for identification of all species except A. brunneus and A. niveoglaucus. Species represented by at least two strains usually gained high or moderate support in ML and BI analyses based on combined data, or CaM and RPB2 genes (Fig. 1, Fig. 3, Fig. 4) except A. aurantiacoflavus, A. glaucus and A. proliferans that were weakly supported in single-gene phylogenies. However, recognition of these species is supported by phenotype, especially by morphology of ascospores (see below). On the other hand, additional strongly supported clades delimited by same analyses (Fig. 1, Fig. 3, Fig. 4) within A. glaucus, A. niveoglaucus and A. proliferans lineages, had no or very limited phenotypic support, which is the reason why we decided for broader species concept rather than for splitting these species.

The A. chevalieri clade includes A. chevalieri, A. costiformis, A. cristatus, A. intermedius, A. montevidensis and two new species A. caperatus and A. porosus. Aspergillus caperatus is represented by CBS 141774 from South Africa. Aspergillus porosus is represented by five strains originating from Turkey and Israel (CBS 141770, CBS 375.75, DTO 308-D1, DTO 262-D2, DTO 262-D4), they formed a clade with full support that is related to A. caperatus, A. intermedius and A. montevidensis (Fig. 1). The topology of this subclade is identical in single-gene phylogenies and all lineages are strongly supported (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). The rest three species in the A. chevalieri clade cluster together and form another strongly supported subclade (Fig. 1) with highly congruent topology shown in single-gene phylogenies (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Aspergillus spiculosus (ex-type: CBS 377.75) is included in the A. intermedius lineage; A. hollandicus (ex-type: CBS 518.65), A. heterocaryoticus (ex-type: CBS 410.65) and A. vitis (ex-type: CBS 651.74) in the A. montevidensis lineage.

The remaining taxa belonging to sect. Aspergillus were distantly related to species from these three main clades and formed remote lineages with not fully resolved or basal position in the trees. Aspergillus cibarius and strain CBS 141766 (described below as A. endophyticus) were resolved in a basal position adjacent to A. ruber and A. glaucus clades (Fig. 1); their position varies between single-gene trees (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Aspergillus xerophilus and closely related A. osmophilus form A. xerophilus clade, A. leucocarpus, A. tamarindosoli and A. teporis formed basal lineages distantly related to core species of sect. Aspergillus (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

ITS sequences do not contain sufficient variation for distinguishing among sect. Aspergillus species (Fig. 5), and therefore this locus was excluded from the combined phylogenetic analysis. Only five species had unique ITS sequences (A. tamarindosoli, A. xerophilus, A. osmophiluc, A. leucocarpus and A. teporis; Fig. 5); identical sequence is shared for species from the A. chevalieri clade (n = 7); A. appendiculatus and A. mallochii; and A. ruber and A. zutongqii. All remaining species (n = 15) are indistinguishable by ITS sequences. Intraspecific single-nucleotide polymorphisms were observed in sequences of A. proliferans, A. tonophilus, A. intermedius, A. costiformis and A. chevalieri.

Fig. 5.

A 50 % majority rule Maximum likelihood consensus tree based on ITS sequences. Maximum likelihood bootstrap proportion (bs) and Bayesian posterior probability (pp) are appended to nodes; only bs ≥ 70 % and pp ≥ 95 % are shown, lower supports are indicated with a hyphen, whereas asterisks indicate full support (100 % bs or 1.00 pp); ex-type strains are designated by a superscript T. The tree is rooted with Hamigera avellanea NRRL 1938T.

Peterson (2008) accepted 15 species in sect. Aspergillus based on congruence analysis of BenA, CaM, ID and RPB2. Fourteen sexual species were placed under the Eurotium name, the only anamorphic species A. proliferans formed a monophylic group with two ascomata producing strains identified as “Eurotium rubrum” and “E. mangini” (NRRL 71 and NRRL 114). The phylogenetic identity of anamorphic ex-type strain NRRL 1908 and other ascosporic strains was additionally supported by Hubka et al. (2012) and Asgari et al. (2014). Hubka et al. (2013a) applied the GCPSR criteria in sect. Aspergillus based on the same four loci and adopted Aspergillus names for Eurotium species. In their study, 17 species were accepted, all of which can be distinguished by CaM or RPB2 loci, and the concept of A. proliferans was extended by a description of its sexual state. In this study, 31 well-supported phylogenetic lineages representing species are recognized. This conclusion is based on phylogenetic analysis of concatenated and partitioned sequence data, comparison of topologies of single-gene phylogenetic trees and reflection of phenotypic data (see below). All species can be distinguished by CaM or RPB2 sequences, while BenA can be used to identify 29 species, with A. brunneus and A. niveoglaucus sharing identical BenA sequences.

Morphology and physiology

Members of sect. Aspergillus are generally characterized by yellow cleistothecia (the only exception is A. leucocarpus, which produces white cleistothecia), lenticular, hyaline ascospores, uniseriate conidiophore heads and globose, subglobose or ellipsoidal conidia. In the past, colony appearance, ascospore and conidial morphology were emphasized to differentiate species in this section (Thom and Raper, 1941, Thom and Raper, 1945, Raper and Fennell, 1965, Blaser, 1975, Kozakiewicz, 1989, Sun and Qi, 1994, Guarro et al., 2012). This led to many species recognized which do not necessarily correspond to species based on recent phylogenetic data.

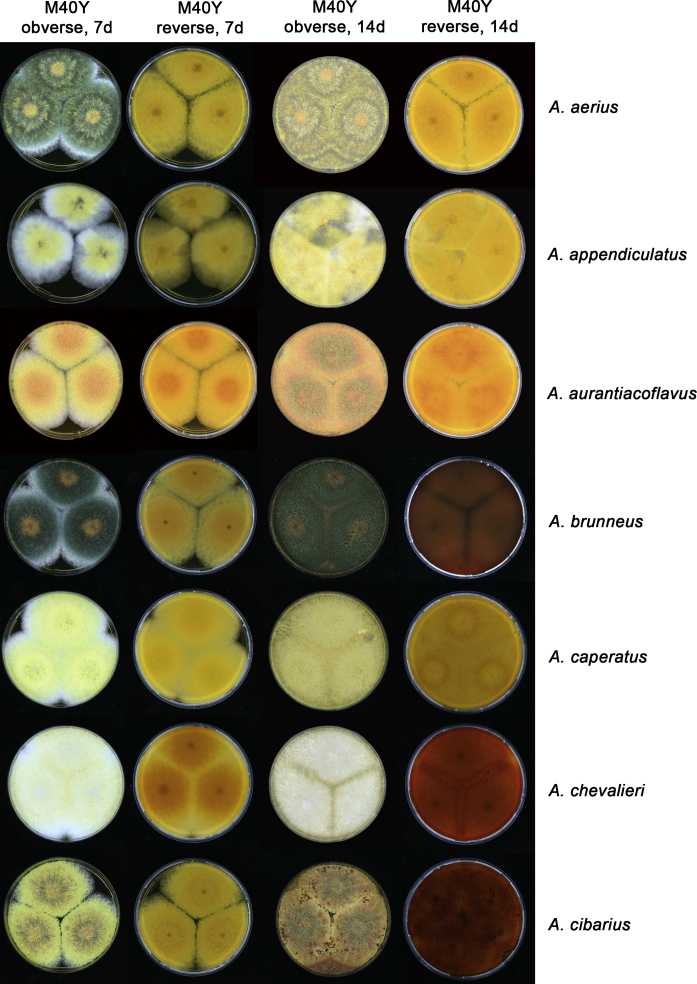

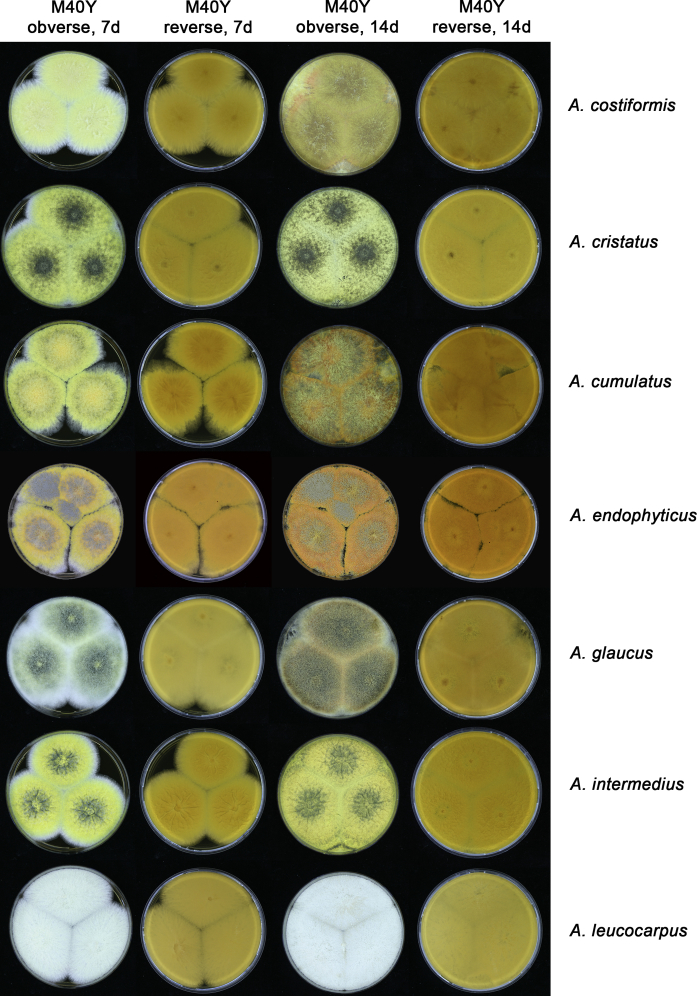

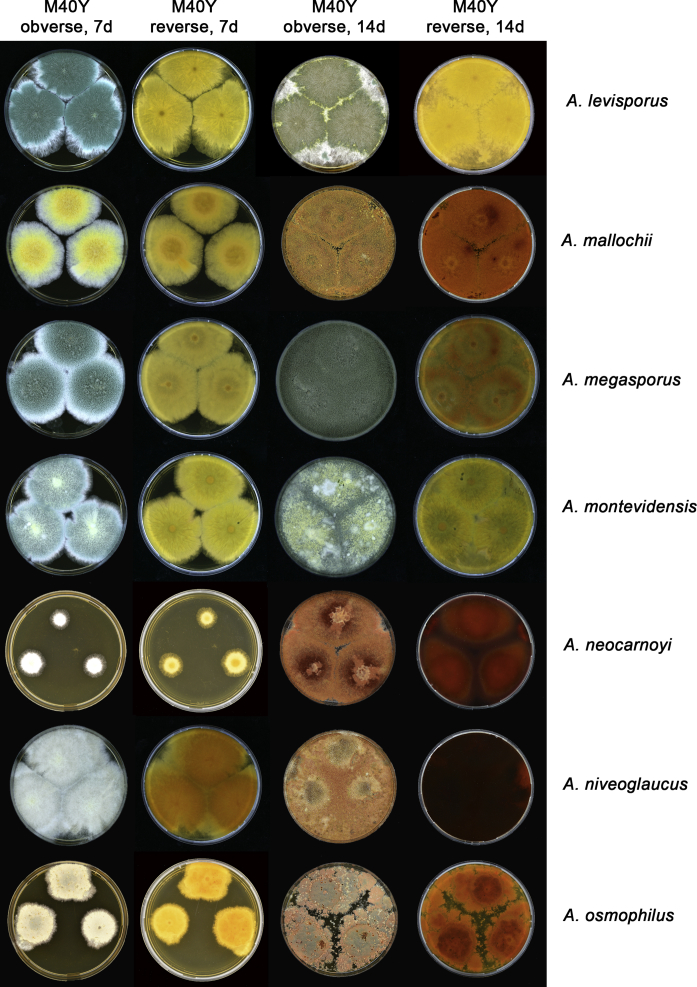

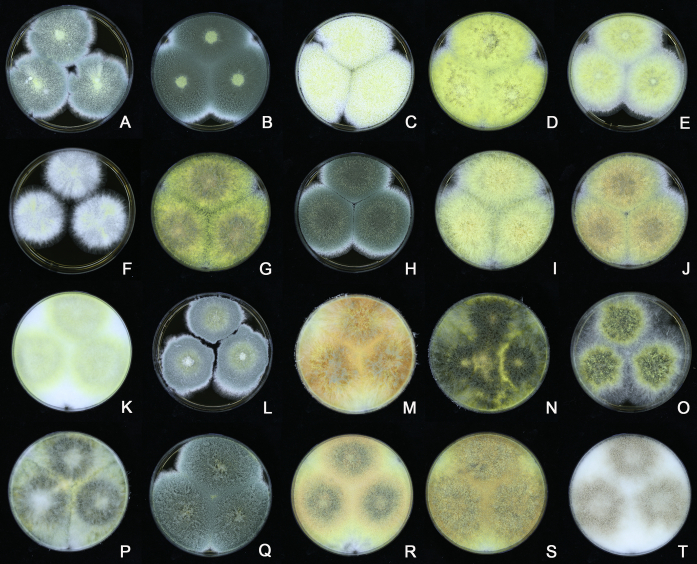

Macromorphology

The colony appearance is highly variable within a species. The ratio of asexual and sexual structures can greatly influence the colony appearance (Thom and Raper, 1941, Thom and Raper, 1945, Raper, 1957, Raper and Fennell, 1965). Some strains of A. brunneus, A. sloanii and A. proliferans do not produce sexual structures. On the contrary, anamorphic structures are absent in some strains of A. costiformis and A. cristatus. Hubka et al. (2013a) reported that the anamorph of these species can be induced by decreasing the water activity of the medium and simultaneously raising the incubation temperature. Red-pigmented mycelium was used to distinguish A. ruber from other related species (Raper and Fennell, 1965, Pitt, 1985, Klich, 2002), but can also occur after two weeks in some isolates of A. brunneus, A. cibarius, A. glaucus, A. niveoglaucus, A. proliferans and A. zutongqii (Fig. 13, Fig. 14, Fig. 15, Fig. 16, Fig. 17). Therefore, it cannot be used as a distinguishing character for these species. White conidial heads were used for distinguishing A. niveoglaucus and A. glaucus (Thom and Raper, 1941, Thom and Raper, 1945, Raper and Fennell, 1965), however, green spored A. niveoglaucus strains were reported by Hubka et al. (2013a) and are also confirmed in this study. Other examples include A. montevidensis CBS 410.65 (ex-type of A. heterocaryoticus) and A. ruber CBS 464.65 (ex-type of A. athecius) which produce white or vinaceous buff conidial head, respectively (Fig. 12). Based on these examples, the conidial head colour should not be used as a single distinguishing character either.

Fig. 13.

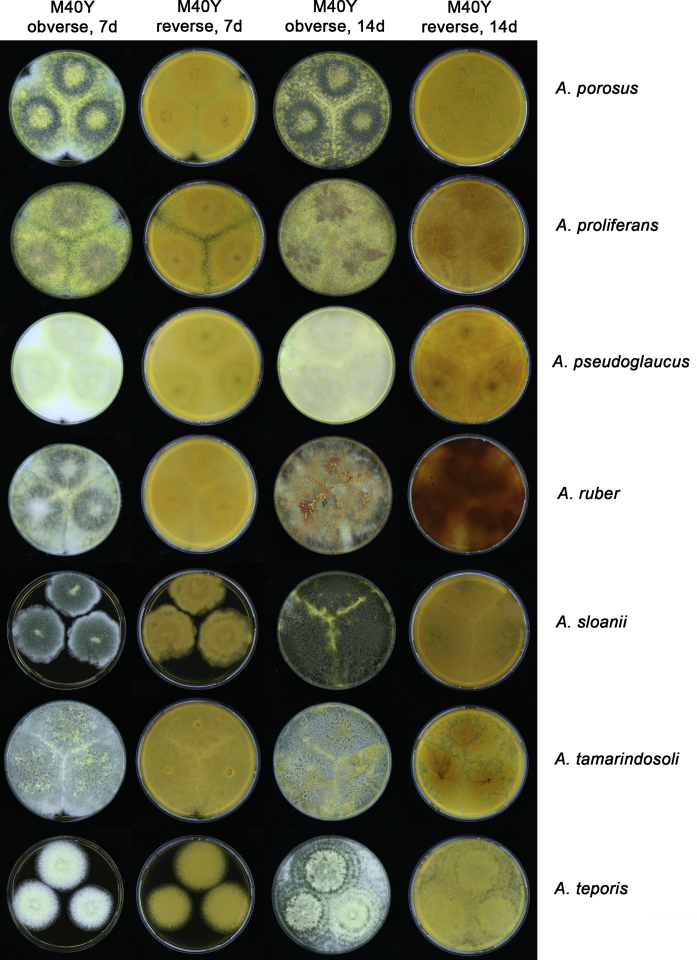

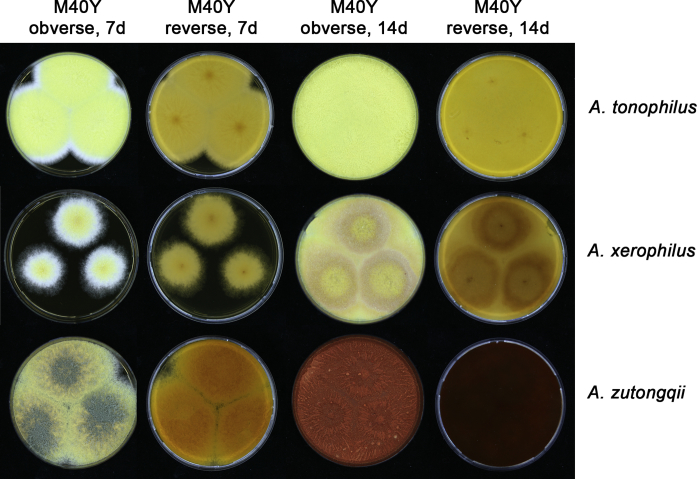

Growth comparison of Aspergillus sect. Aspergillus species on M40Y for 7 d and 14 d at 25 °C.

Fig. 14.

Growth comparison of Aspergillus sect. Aspergillus species on M40Y for 7 d and 14 d at 25 °C.

Fig. 15.

Growth comparison of Aspergillus sect. Aspergillus species on M40Y for 7 d and 14 d at 25 °C.

Fig. 16.

Growth comparison of Aspergillus sect. Aspergillus species on M40Y for 7 d and 14 d at 25 °C.

Fig. 17.

Growth comparison of Aspergillus sect. Aspergillus species on M40Y for 7 d and 14 d at 25 °C.

Fig. 12.

Diversity of macromorphology (colonies on M40Y, 25 °C, 7 d) within Aspergillus sect. Aspergillus species. A–E.A. montevidensis. From left to right: CBS 491.65T, CBS 651.74 (ex-type of A. vitis), CBS 410.65, CBS 518.65 (ex-type of A. hollandicus), CBS 111.52. F–J.A. proliferans. From left to right: CBS 121.45T, DTO 322-A2, CCF 4096, CCF 5395, CCF 5392. K–O.A. pseudoglaucus. From left to right: CBS 123.28T, CBS 101747 (ex-type of A. fimicola), CBS 379.75 (ex-type of A. glaber), DTO 147-G3, CGMCC 3.00460. P–T.A. ruber. From left to right: CBS 530.65T, DTO 238-C4, CBS 101748 (ex-type of A. tuberculatus), CBS 104.18, CBS 464.65 (ex-type of A. athecius).

Physiology

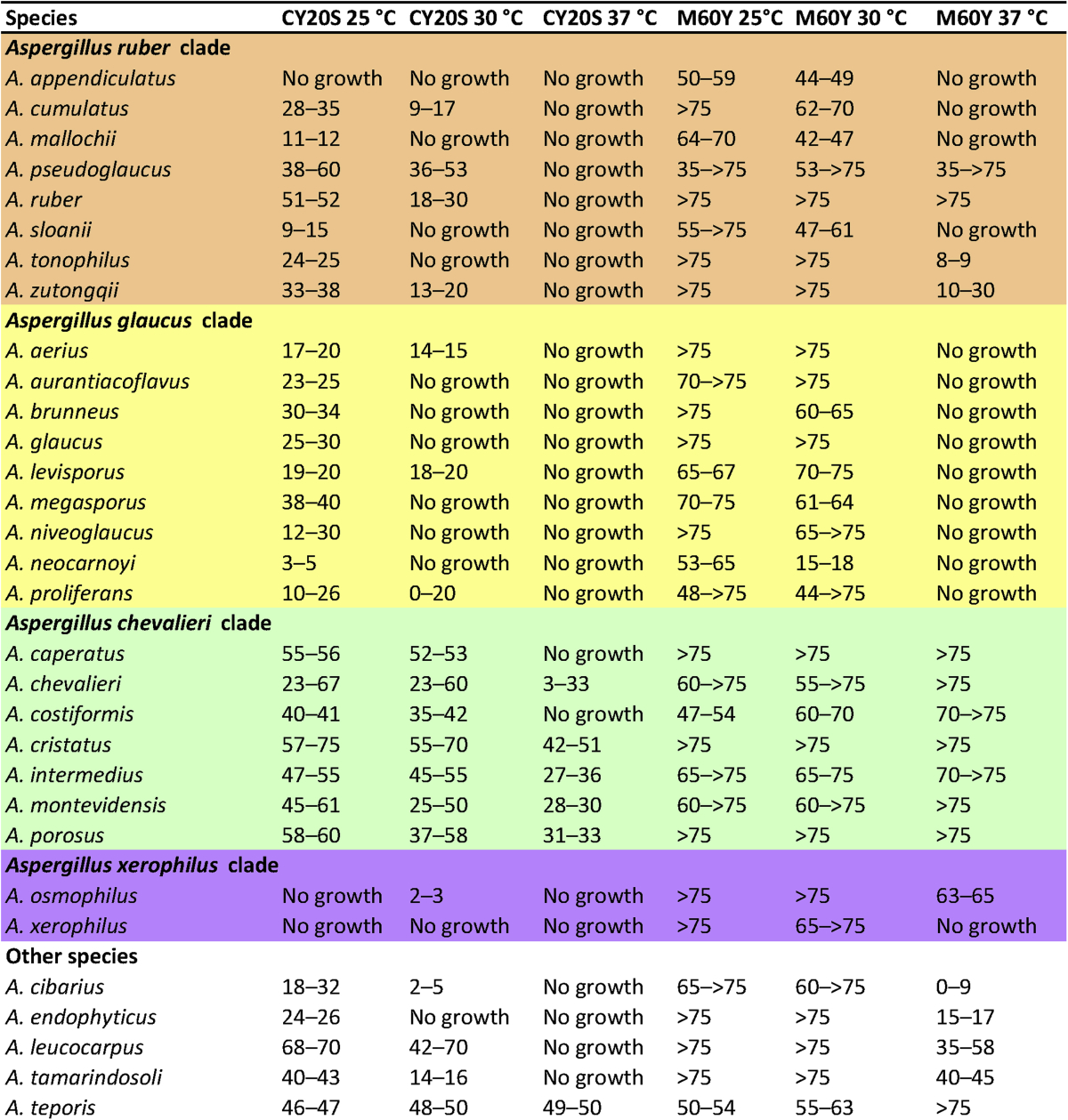

Growth rates at higher temperatures show certain correlation with phylogenetic topologies, most species in the A. chevalieri clade (except A. costiformis and A. caperatus) grow on CY20S at 37 °C, while all species in the A. ruber and A. glaucus clades do not grow under this condition. Growth profiles on M60Y at 37 °C show a similar pattern with CY20S 37 °C. The only difference is that several species from the A. chevalieri and A. ruber clades including A. caperatus, A. costiformis, A. pseudoglaucus, A. ruber, A. tonophilus and A. zutongqii grow on M60Y at 37 °C, but show no growth on CY20S at 37 °C (Table 5). The growth ability on CY20S and M60Y at 37 °C together with the size and surface morphology of ascospores were found to correlate mostly with the phylogenetic species concept in this section (Hubka et al. 2013a). This conclusion is confirmed in this study using a world-wide section Aspergillus strains, and we found the growth ability on CY20S and M60Y at 37 °C a reliable feature for distinguishing morphologically similar species. For example, A. proliferans and A. ruber share similar smooth or slightly rough, furrowed ascospores and tuberculate conidia, among them A. proliferans cannot grow on M60Y at 37 °C, while A. ruber grows well on M60Y at 37 °C. The growth ability on media with high water activity (CYA, MEA) is also useful diagnostic features for certain species. Most species in sect. Aspergillus grow restrictedly on these two media, some species like A. appendiculatus, A. neocarnoyi, A. osmophilus, A. tonophilus and A. xerophilus show more xerophilic abilities compare to others and do not grow on CYA and MEA at all.

Table 5.

Temperature growth profiles (mm) of section Aspergillus species.

Colour codes: yellow = A. glaucus clade, orange = A. ruber clade, green = A. chevalieri clade, purple = A. xerophilus clade.

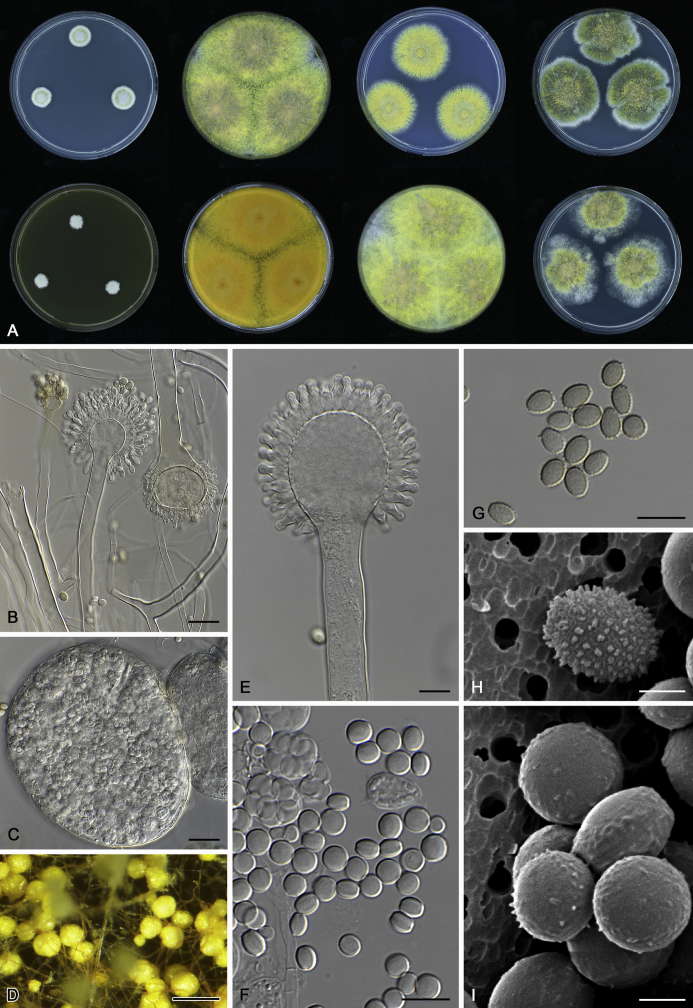

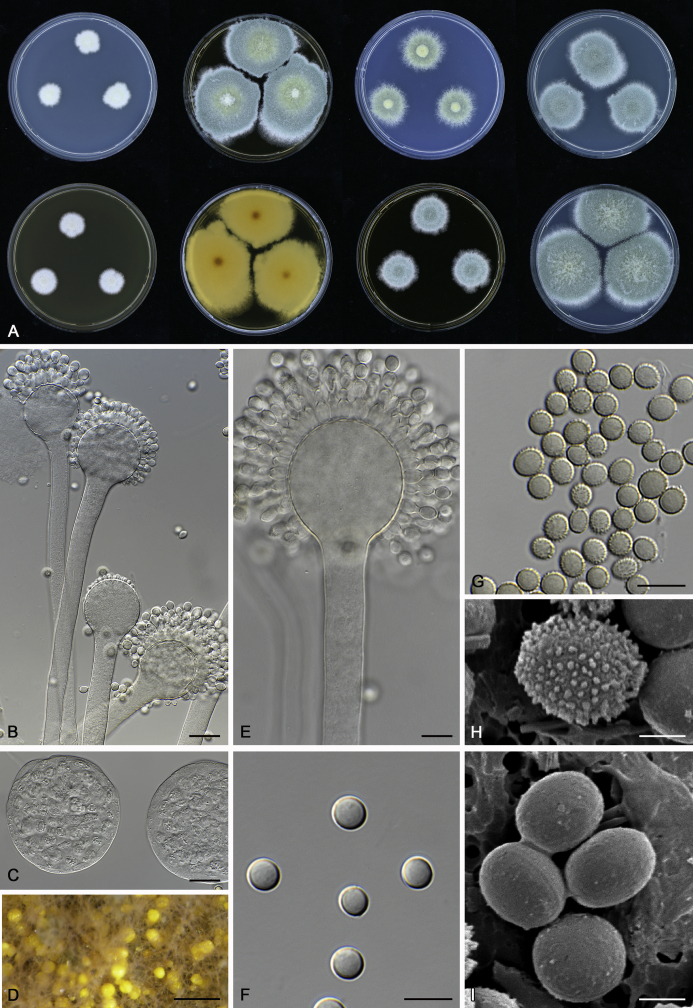

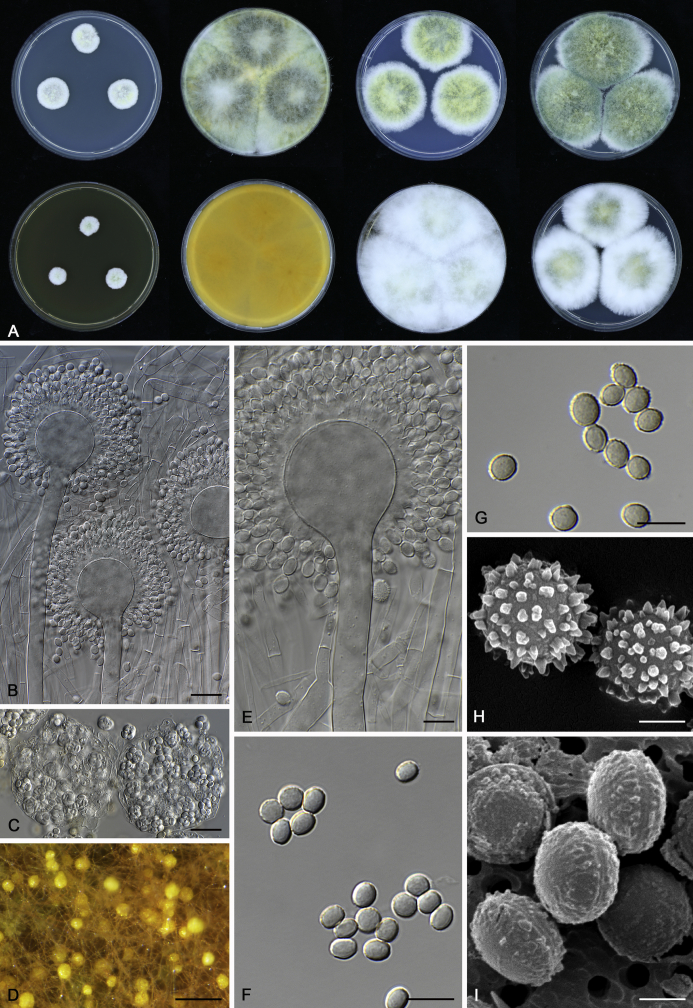

Micromorphology

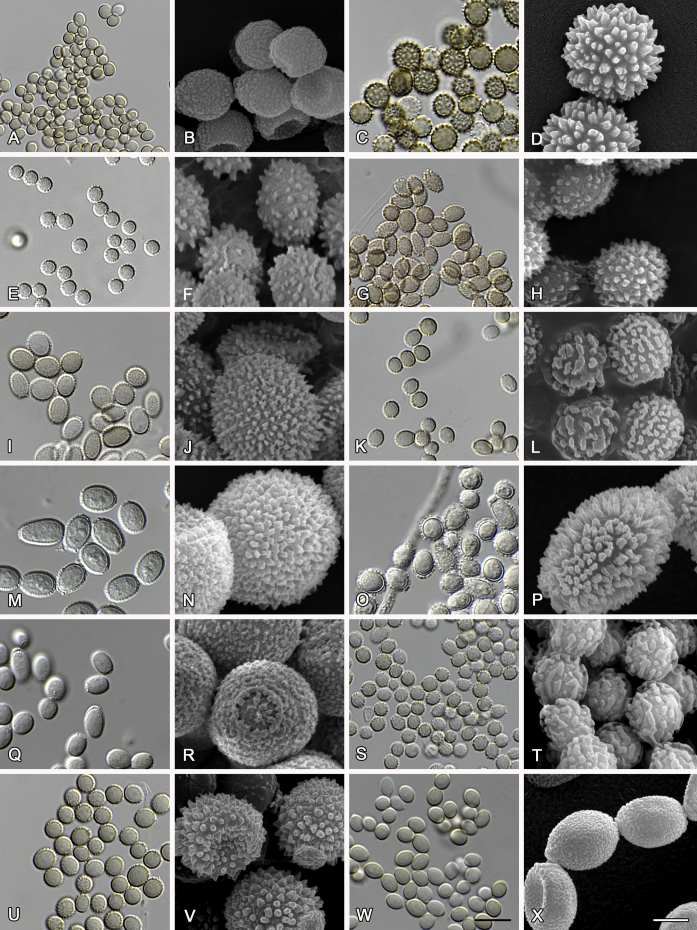

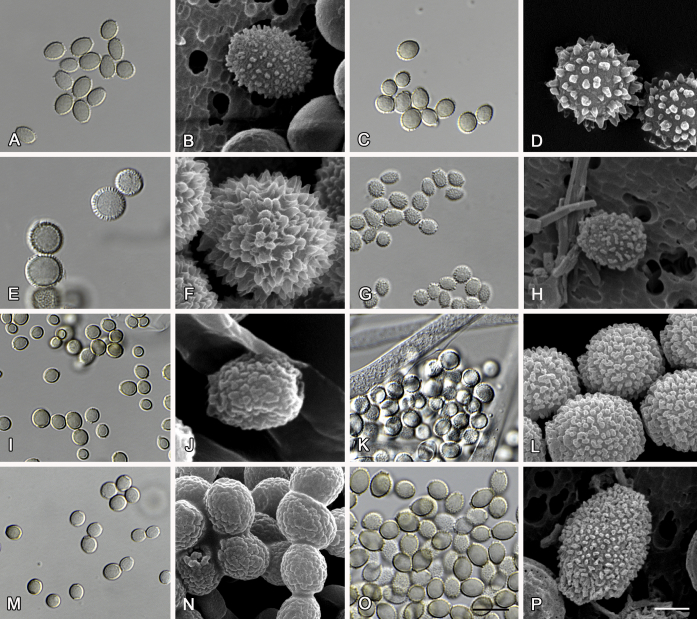

Compared to colony appearance, micro-morphological characters within a species are relatively stable and informative (Table 6). The size and ornamentation of ascospores are generally the most informative phenotypic characters for species recognition (Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8). Large ascospores (spore bodies average > 6.5 μm) are produced by A. aerius, A. brunneus, A. costiformis, A. glaucus, A. neocarnoyi, A. niveoglaucus, A. osmophilus and A. zutongqii; small ascospores (spore bodies < 5 μm) are produced by A. caperatus, A. intermedius, A. levisporus and A. tamarindosoli, while remaining species produce intermediate ascospores. Convex sides of ascospores can be smooth, verruculose or rugulose, and these ornamentations are generally stable with only minor intraspecific variability. However, in some rare cases, the ascospore morphology differs within a species. For example, most A. ruber strains produce smooth ascospores with minute rough ornamentations along equatorial ridges, but CBS 101748, previously described as A. tuberculatus (Sun & Qi 1994), has tuberculate ascospores (Fig. 8). Variations were also found in A. montevidensis, strain CCF 4248 has similar ascospores with A. tuberculatus, but shows identical sequences, growth parameters and colony phenotype with A. montevidensis (Hubka et al. 2013a), and another atypical strain CCF 4070 has smooth or slightly rough ascospores. It is noteworthy that ascospore ornamentation is related to the stage of development, and fine structures and ornamentation can be overlooked when observed using a light microscope (Blaser, 1975, Kozakiewicz, 1989, Guarro et al., 2012, Hubka et al., 2013a). In addition, some species are morphologically slightly different even when observed under SEM, and therefore careful comparison with experience is needed for morphological identification. Aspergillus parviverruculosus was introduced based on CGMCC 3.04665 producing verruculose ascospores (Kong & Qi 1995), Hubka et al. (2013a) considered it synonymous with A. niveoglaucus based on phylogenetic analysis and they observed appendaged ascospores. We confirmed the appendages in immature ascospores of the ex-type of A. parviverruculosus (CGMCC 3.04665). Filiform appendages were also observed in immature ascospores of A. appendiculatus (Kozakiewicz, 1989, Hubka et al., 2013a) and these appendages can merge with ascospore body and form petaliform crests. Appendaged ascospores are also presented in A. filifer and A. qinqixianii in Aspergillus subgenus Nidulantes; however, these appendages are consistently presented in mature ascospores (Horie et al., 2000, Zalar et al., 2008, Chen et al., 2016).

Table 6.

Most important micromorphological characters for section Aspergillus species (μm).

| Species | Teleomorphic characters |

Anamorphic characters |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomata | Spore bodies | Ornamentation of convex surface | Furrow | Crests | Conidiophores | Vesicles | Phialides | Conidia | |

| Aspergillus aerius | 190–275 | 6.5–8 × 4.5–6 | Smooth, rough along equatorial ridges | Present | Absent | 500–1 000 × 7–15.5 | 26–41 | 7.5–12.5 × 5–8 | Tuberculate, (5–)10–13 × 6–10 |

| A. appendiculatus | 100–225 | 5–7.5 × 4–5.5 | Slightly rough | Absent or showing as a trace | Filiform appendages or petaliform, petals 1–1.5 μm at high parts | 800–2 000 × 7–12(–14.5) | 30–64 | 8–16 × 4.5–7.5 | Tuberculate, 5–10(–12) × 5–7(–8.5) |

| A. aurantiacoflavus | 110–250 | 4–5.5 × 3–5 | Verruculose | Present | Irregular, <0.5 | 250–800 × 7.5–12 | 30–45 | 6–11 × 3.5–6.5 | Tuberculate, 5–9 × 4–7 |

| A. brunneus | 110–240 | 7–10 × 6–8 | Rough along equatorial ridges | Present | Irregular, <0.5 | 700–1 200 × 7–18 | 32–58 | 10–18.5 × 7–12.5 | Tuberculate, 8–15 × 8–13 |

| A. caperatus | 130–220 | 3.5–4.5 × 2.5–4 | Verruculose to rugulose | Pronounced | 0.5–1 | 250–500 × 6.5–9(–12) | 26–45 | 7.5–12 × 4–7.5 | Lobate-reticulate, 3.5–5.5 × 3.5–4.5 |

| A. chevalieri | 100–250 | 3.5–5.5 × 3–4 | Smooth to slightly verruculose | Present | 0.5–1 | 200–1 000 × 6–12 | 23–47 | 5.5–7.5(–10) × 3–5 | Tuberculate to lobate-reticulate, 3–4(–6) × 2.5–3.5(–5) |

| A. cibarius | 100–200 | 4–5.5 × 3–5 | Rough along equatorial ridges | Present | Irregular, <0.5 | 500–700 × 8–14 | 32–58 | 6–11 × 3–5.5 | Tuberculate, 4–7 × 3.5–5.5 |

| A. costiformis | 100–255 | 5.5–7 × 5–6.5 | Rugulose | Pronounced | 0.5 | 500–800 × 7–13 | 20–45(–60) | 6–9.5 × 3–4.5(–5.5) | Microtuberculate, 4–5.5(–6.5) × 3–4.5(–5.5) |

| A. cristatus | 100–200 | 4.5–6 × 4–6 | Verruculose to rugulose | Present | 1.2–1.5 | 300–500 × (6–)8–12 | (26–)35–51 | 5.5–9 × 3.5–6 | Tuberculate, 4–6.5 × 3.5–5 |

| A. cumulatus | 100–200 | 4–6 × 3.5–5 | Slightly rough | Pronounced | Irregular, <0.5 | 500–1 300 × 7–15 | 32–57 | 7–12 × 4.5–7.5 | Tuberculate, 5–8 × 4–7.5 |

| A. endophyticus | 120–200 | 4–5.5 × 3–4.5 | Verruculose to rugulose | Pronounced | 0.5–1 | 350–800 × 9.5–14 | 32–52 | 6–10 × 3.5–5.5 | Tuberculate to lobate-reticulate, 5.5–8 × 4.5–6 |

| A. glaucus | 120–250 | 5.5–7.5 × 3.5–6 | Smooth, minute rough along equatorial ridges | Pronounced | Irregular, 0.5–1 | 150–500 × 10–21(–30) | 30–60 | (8–)12–20 × (4–)5–8.5 | Tuberculate, 6–12.5 × 5.5–9 |

| A. intermedius | 100–250 | 3.5–5 × 3–4.5 | Verruculose to rugulose | Present | 0.5 | 250–600 × 7.5–13 | (26–)40–60 | 5.5–7.5(–9) × 3–5.5 | Microtuberculate, 3–4(–6) × 3–4.5 |

| A. leucocarpus | 80–140 | 4.5–5.5 × 3.5–5 | Verruculose | Present | 0.8–1.5 | 800–1 400 × 7.5–12 | 35–60 | 8–11.5 × 3.5–6.5 | Tuberculate, 5.5–9 × 5–8 |

| A. levisporus | 70–130 | 3–4.5 × 2.5–4 | Smooth | Present | Absent | 400–600 × 10–14 | 30–44 | 6–8.5 × 3.5–6 | Tuberculate to lobate-reticulate, 3.5–4.5 × 2.5–4 |

| A. mallochii | 130–220 | 4–6 × 3–5 | Smooth, minute rough along equatorial ridges | Absent or showing as a trace | Petaliform, 1–2 at high parts | 600–1 500 × 6–9.5(–12) | 27–43 | 6.5–9 × 3–5 | Tuberculate, 4.5–7 × 4–5.5 |

| A. megasporus | 110–300 | 4–6.5 × 3.5–5.5 | Smooth, rough along equatorial ridges | Present | Absent or indefinite | 1 000–1 500 × 6.5–12(–21.5) | 30–54 | 7.5–14 × 4–7.5 | Tuberculate, 7–14 × 5–8.5 |

| A. montevidensis | 80–250 | 4–6 × 3–4.5 | Generally rugulose, smooth or slightly rough in atypical strain CCF 4070, tuberculate in atypical strain CCF 4248 | Pronounced | 0.5 | 250–500 × 6–13.5 | 25–35(–50) | 5–8.5(–11) × 3–6 | Lobate-reticulate, 4–6.5 × 3.5–5 |

| A. neocarnoyi | 120–230 | 6.5–9 × 4.5–7 | Verruculose to rugulose | Present | Absent or indefinite | 1 000–2 000 × (9–)12–23 | (32–)50–92 | 12–21 × 6–9 | Tuberculate, 8–15.5 × 6–10 |

| A. niveoglaucus | 90–240 | (4.5–)5.5–7.5 × (3–)5–6 | Rough along equatorial ridges or verruculose to rugulose | Present | Irregular, <0.5 | 1 000–1 500 × (7.5–)10–23 | (31–)55–85 | 8–14(–20) × 4–7(–11) | Tuberculate, (6–)8–13.5 × 4–9 |

| A. osmophilus | 100–350 | 7–9 × 6–7.5 | Verruculose | Pronounced | 0.5 | 300–1 000 × 7.5–12 | 28–46 | 9–12 × 4.5–7 | Microtuberculate to tuberculate, 6–8.5 × 5.5–7.5 |

| A. porosus | 80–230 | 3.5–5.5 × 3–4.5 | Rugulose, pitted | Pronounced | 0.5 | 250–600 × 5–12.5 | 24–58 | 5–10 × 2.5–5 | Lobate-reticulate, 3.5–5.5 × 2.5–4.5 |

| A. proliferans | 100–240 | 4–6 × 3–5 | Smooth or slightly verruculose or rough along equatorial ridges | Present or pronounced | Absent | 250–1 000 × 8–16.5 | 20–50 | 6–12 × 3–5.5 | Tuberculate, 5–7.5(–10) × 4–6(–7) |

| A. pseudoglaucus | 75–200 | 4–6.5 × 3–4.5 | Smooth or slightly rough | Absent or showing as a trace | Absent | 500–1 000 × (7–)11–22 | (26–)37–65 | 6–11 × 4–6.5 | Tuberculate; microtuberculate in atypical strain CBS 379.75, (3.5–)6–9 × (3–)5.5–7.5 |

| A. ruber | 50–175 | 4–6 × 3.5–5 | Generally smooth or minute rough along equatorial ridges, tuberculate in atypical strain CBS 101748 | Present or pronounced | Absent | 500–750 × 7–13.5 | 25–48 | 7–9(–12) × 3.5–6 | Tuberculate, (4.5–)7–9(–12) × 4–6(–8) |

| A. sloanii | 60–205 | 4–6 × 3–4.5 | Smooth, minute rough along equatorial ridges | Present | Absent | 160–900 × 7.5–16 | (10–)34–53 | (7.5–)9–13.5(–18) × (5–)7–9.5 | Tuberculate, 5.5–9.5 × 5.5–9 |

| A. tamarindosoli | 130–240 | 3.5–5 × 3–4 | Verruculose | Present | Irregular, 0.5–1.5 | 700–1 000 × 10–15 | 40–72 | 6.5–12 × 4–5.5 | Lobate-reticulate, 4–7 × 3–4.5 |

| A. teporis | 120–180 | 5–6.5 × 4–5.5 | Slightly verruculose | Pronounced | 0.5 | 800–1 200 × 8–19 | 33–53 | 7–12 × 3.5–5 | Lobate-reticulate, 3.5–6 × 3–4.5 |

| A. tonophilus | 100–235 | 4–6 × 3–4.5 | Verruculose | Present | Absent | 120–500 × 7–12.5 | 25–44 | 6–11 × 3–5 | Tuberculate to lobate-reticulate, 5–7.5 × 3.5–6 |

| A. xerophilus | 165–330 | 4.5–6.5 × 3.5–5 | Verruculose | Present | Irregular, <0.5 | 50–200 × 6.5–9.5(–12) | 40–66 | 6–9 × 3.5–6 | Microtuberculate, 3.5–5.5 × 3–4.5 |

| A. zutongqii | 110–220 | 6–7.5 × 4.5–6 | Verruculose | Pronounced | Absent | 150–500 × 7.5–13 | 25–40 | 8–12 × 4–6.5 | Tuberculate, 5.5–10 × 4–7 |

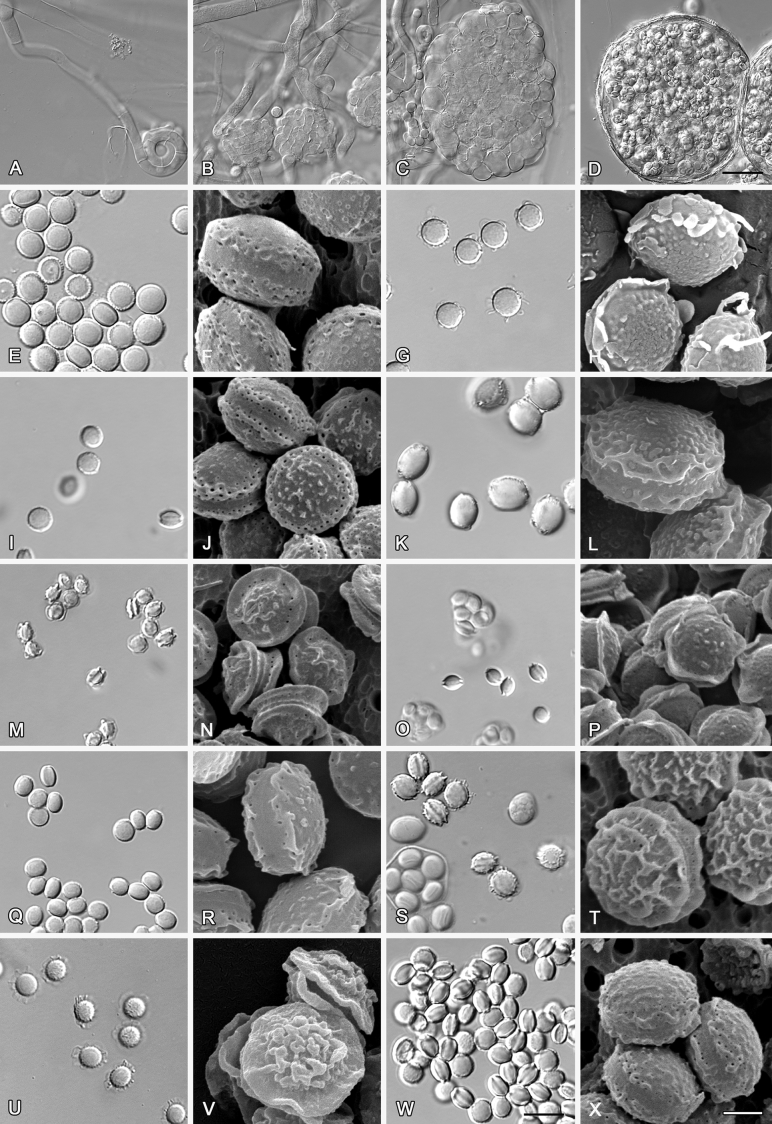

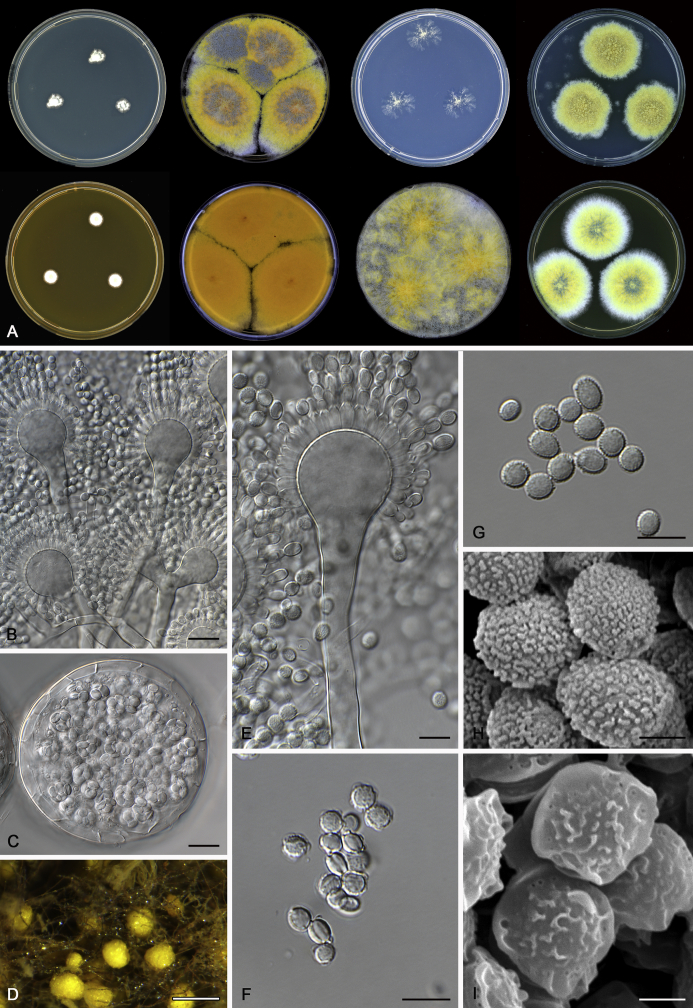

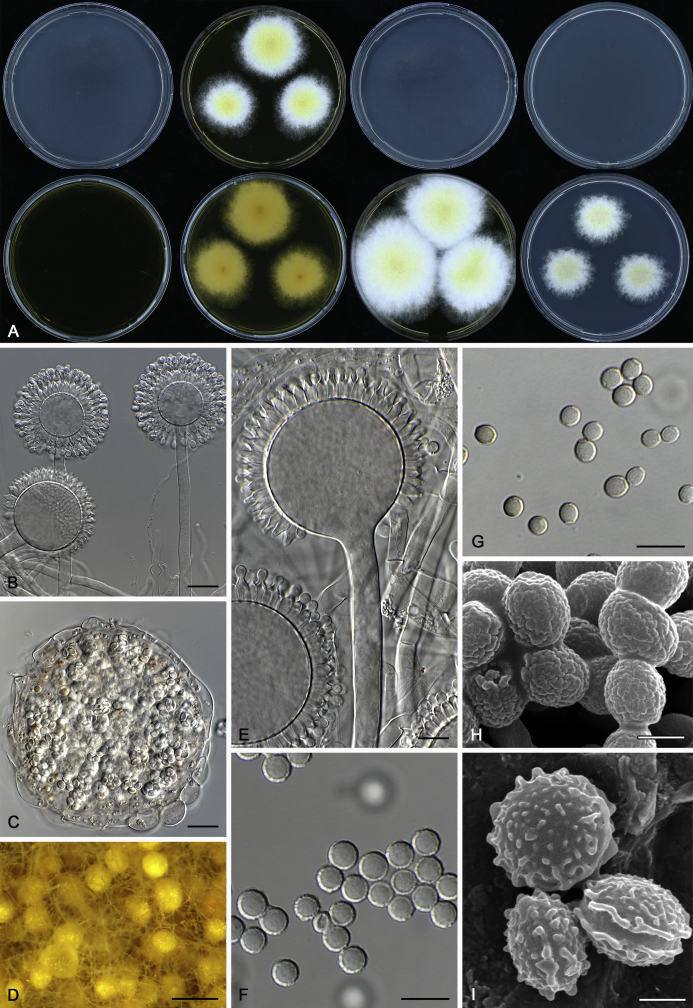

Fig. 6.

Formation of ascomata and range of ascospore phenotypes. A–D. Initials and ascomata. E, F.Aspergillus aerius CBS 141771T. G, H.A. appendiculatus CBS 374.75T. I, J.A. aurantiacoflavus CBS 141930T. K, L.A. brunneus CBS 112.26T. M, N.A. caperatus CBS 141774T. O, P.A. chevalieri CBS 522.65T. Q, R.A. cibarius KACC 46346T. S, T.A. costiformis CBS 101749T. U, V.A. cristatus CBS 123.53T. W, X.A. cumulatus KACC 47316T. Scale bars: D = 20 μm, applies to A–C; W = 10 μm, applies to E, G, I, K, M, O, Q, S, U; X = 2 μm, applies to F, H, J, L, N, P, R, T, V.

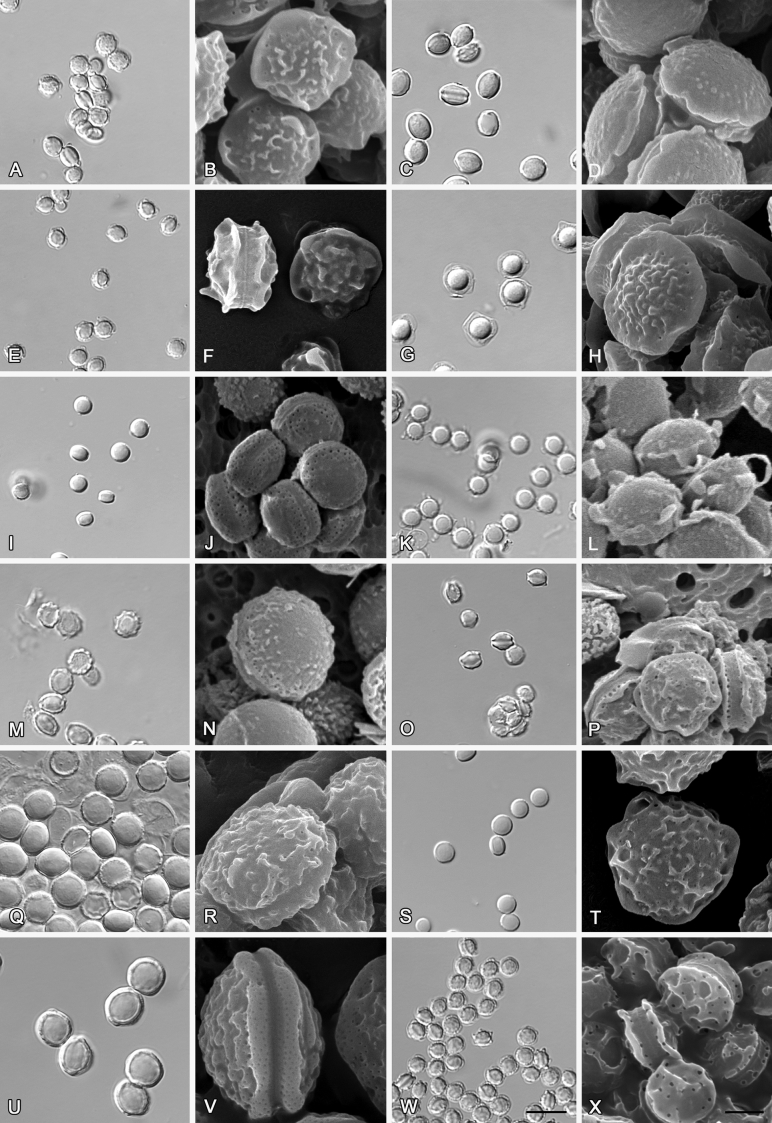

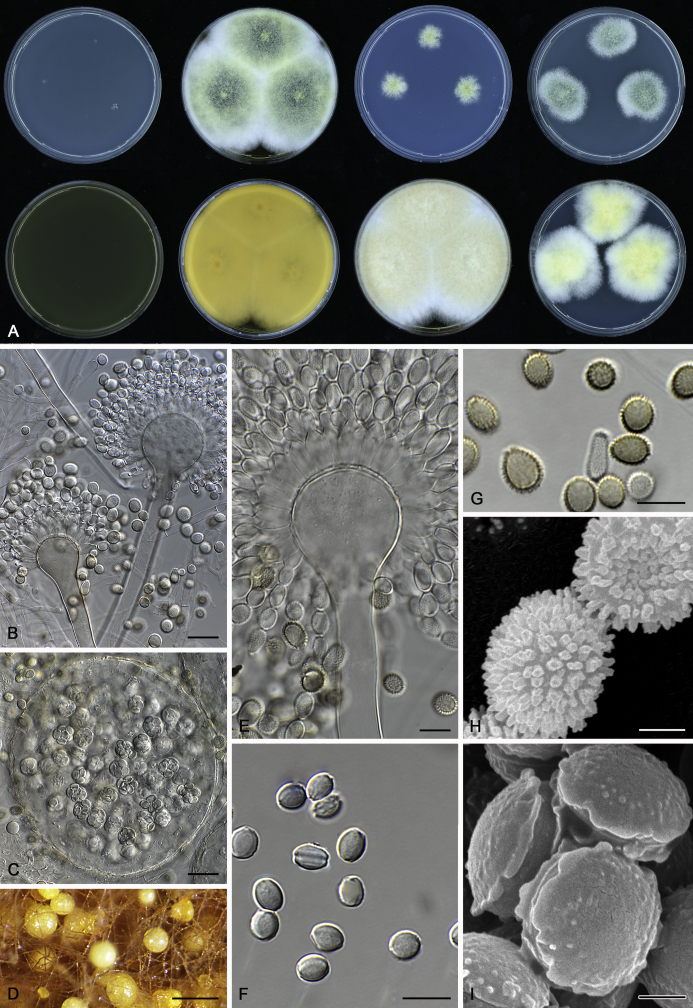

Fig. 7.

Range of ascospore phenotypes. A, B.Aspergillus endophyticus CBS 141766T. C, D.A. glaucus CBS 516.65T. E, F.A. intermedius CBS 523.65T. G, H.A. leucocarpus CBS 353.68T. I, J.A. levisporus CBS 141767T. K, L.A. mallochii CBS 141928T. M, N.A. megasporus CBS 141929T. O, P.A. montevidensis CBS 491.65T. Q, R.A. neocarnoyi CBS 471.65T. S, T.A. niveoglaucus CBS 114.27T. U, V.A. osmophilus CBS 134258T. W, X.A. porosus CBS 141770T. Scale bars: W = 10 μm, applies to A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O, Q, S, U; X = 2 μm, applies to B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P, R, T, V.

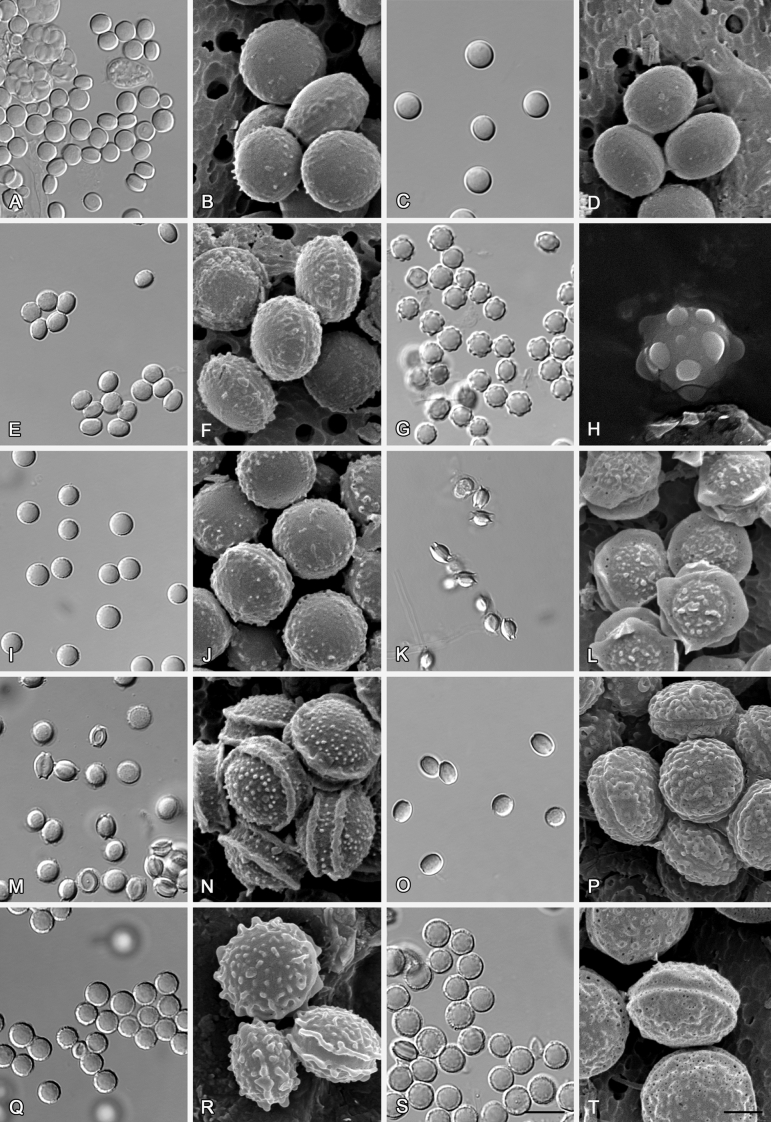

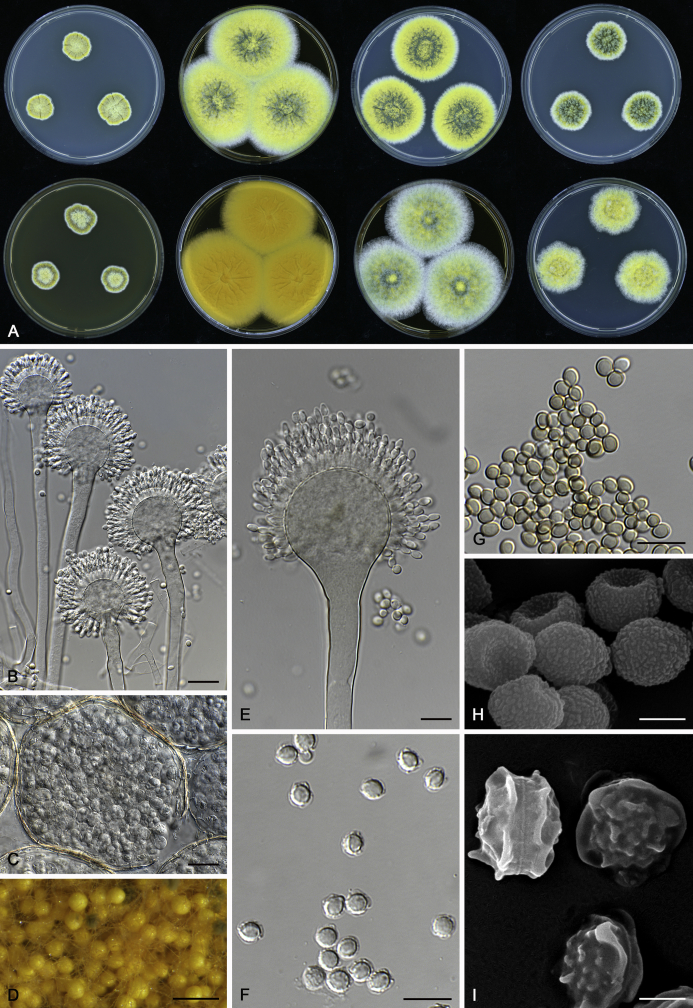

Fig. 8.

Range of ascospore phenotypes. A, B.Aspergillus proliferans DTO 322-A2. C, D.A. pseudoglaucus CBS 101747 (ex-type of A. fimicola). E, F.A. ruber CBS 530.65T. G, H.A. ruber CBS 101748 (ex-type of A. tuberculatus). I, J.A. sloanii CBS 138177T. K, L.A. tamarindosoli CBS 141775T. M, N.A. teporis CBS 141768T. O, P.A. tonophilus KACC 47150. Q, R.A. xerophilus CBS 938.73T. S, T.A. zutongqii CBS 141773T. Scale bars: S = 10 μm, applies to A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O, Q; T = 2 μm, applies to B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P, R.

The diameter and shape of conidia are highly variable within species and generally not useful for species differentiation. However, conidial ornamentation is useful for differentiating phylogenetically related species or species with similar ascospore morphology (Fig. 9, Fig. 10, Fig. 11). For example, A. intermedius is phylogenetically related to A. montevidensis. Both produce verruculose ascospores with 0.5 μm crests, however, the microtuberculate conidia of A. intermedius can easily distinguish it from A. montevidensis. Most species produce consistent conidial ornamentations, except in A. pseudoglaucus where most strains produce tuberculate conidia, but CBS 379.75, previously described as A. glaber (Blaser 1975), produces microtuberculate conidia. Kozakiewicz (1989) assigned the conidial ornamentation into four categories, ranging from microtuberculate, aculeate, tuberculate to lobate-reticulate. Based on our observations, aculeate and tuberculate ornamentations may occur in same species, and can be affected by the fixation methods or age of conidia. We therefore, combined these two types of ornamentation within the tuberculate category. The three categories of conidial ornamentation described here include microtuberculate, tuberculate or lobate-reticulate.

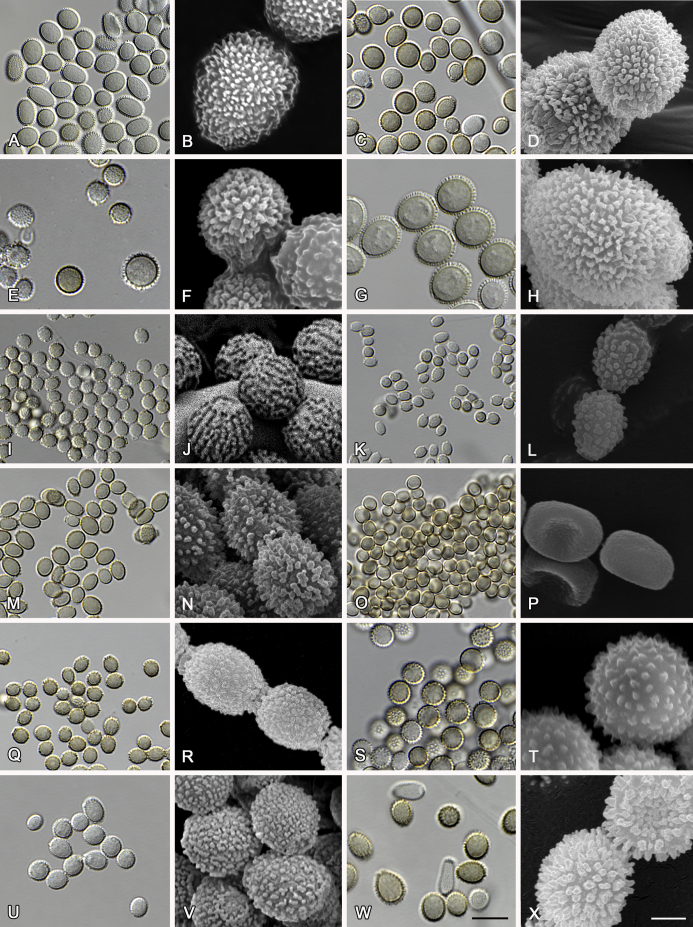

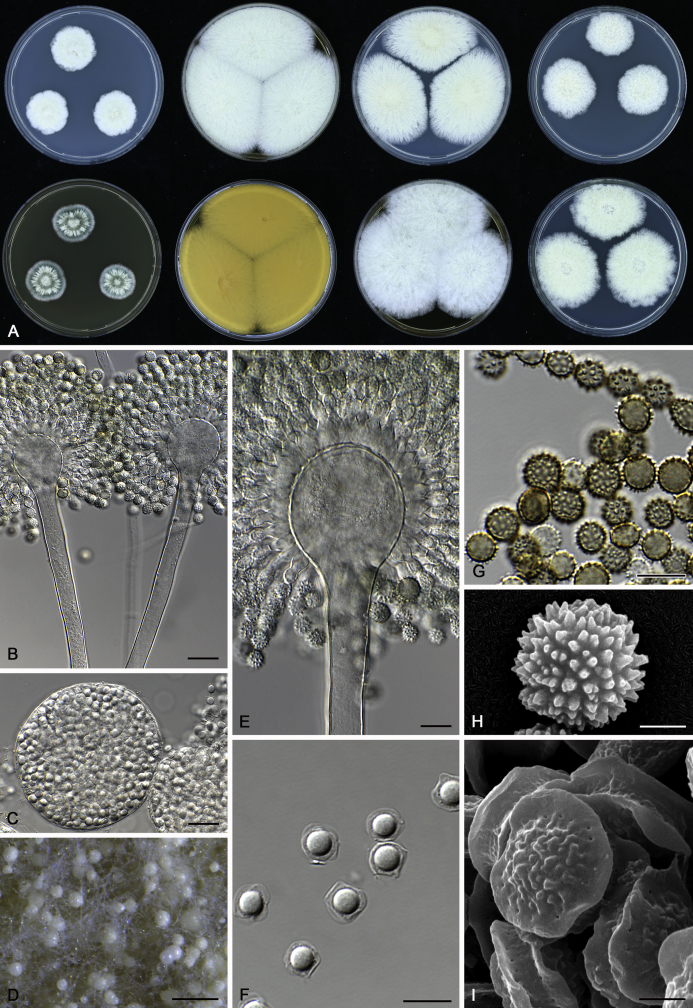

Fig. 9.

Range of conidia phenotypes. A, B.Aspergillus aerius CBS 141771T. C, D.A. appendiculatus CBS 374.75T. E, F.A. aurantiacoflavus CBS 141930T. G, H.A. brunneus CBS 112.26T. I, J.A. caperatus CBS 141774T. K, L.A. chevalieri CBS 522.65T. M, N.A. cibarius KACC 46346T. O, P.A. costiformis CBS 101749T. Q, R.A. cristatus CBS 123.53T. S, T.A. cumulatus KACC 47316T. U, V.A. endophyticus CBS 141766T. W, X.A. glaucus CBS 516.65T. Scale bars: W = 10 μm, applies to A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O, Q, S, U; X = 2 μm, applies to B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P, R, T, V.

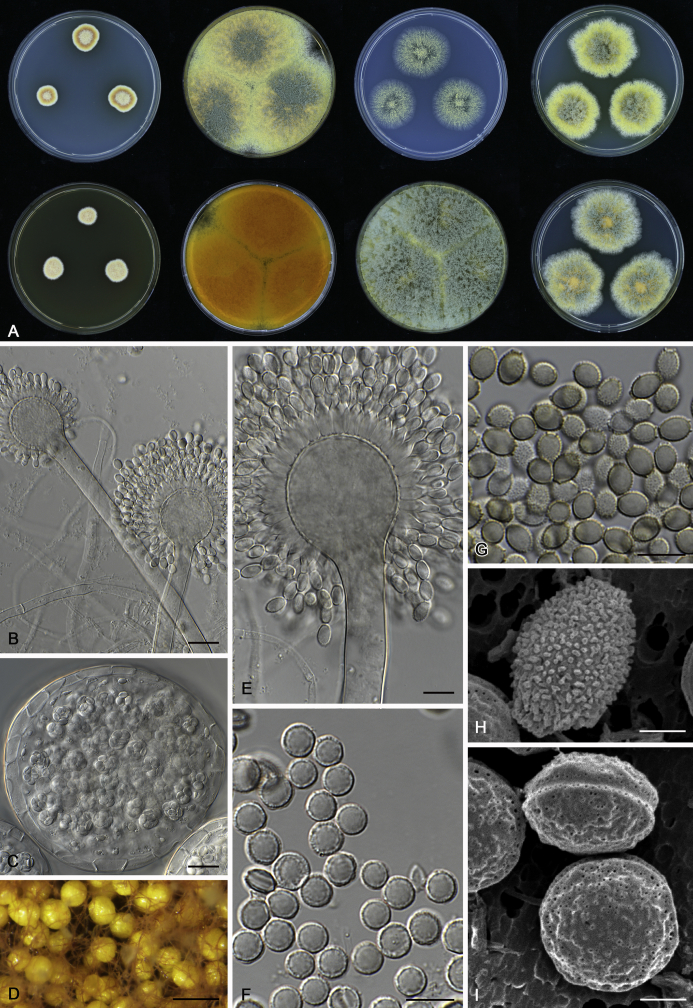

Fig. 10.

Range of conidia phenotypes. A, B.Aspergillus intermedius CBS 523.65T. C, D.A. leucocarpus CBS 353.68T. E, F.A. levisporus CBS 141767T. G, H.A. mallochii CBS 141928T. I, J.A. megasporus CBS 141929T. K, L.A. montevidensis CBS 491.65T. M, N.A. neocarnoyi CBS 471.65T. O, P.A. niveoglaucus CBS 114.27T. Q, R.A. osmophilus CBS 134258T. S, T.A. porosus CBS 141770T. U, V.A. pseudoglaucus CBS 101747 (ex-type of A. fimicola). W, X.A. pseudoglaucus CBS 379.75 (ex-type of A. glaber). Scale bars: W = 10 μm, applies to A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O, Q, S, U; X = 2 μm, applies to B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P, R, T, V.

Fig. 11.

Range of conidia phenotypes. A, B.Aspergillus proliferans DTO 322-A2. C, D.A. ruber CBS 530.65T. E, F.A. sloanii CBS 138177T. G, H.A. tamarindosoli CBS 141775T. I, J.A. teporis CBS 141768T. K, L.A. tonophilus KACC 47150. M, N.A. xerophilus CBS 938.73T. O, P.A. zutongqii CBS 141773T. Scale bars: O = 10 μm, applies to A, C, E, G, I, K, M; P = 2 μm, applies to B, D, F, H, J, L, N.

Extrolites