Abstract

We assessed non‐liver‐related non–acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)‐related (NLR‐NAR) events and mortality in a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/hepatitis C virus (HCV)–coinfected patients treated with interferon (IFN) and ribavirin (RBV), between 2000 and 2008. The censoring date was May 31, 2014. Cox regression analysis was performed to assess the adjusted hazard rate (HR) of overall death in responders and nonresponders. Fine and Gray regression analysis was conducted to determine the adjusted subhazard rate (sHR) of NLR deaths and NLR‐NAR events considering death as the competing risk. The NLR‐NAR events analyzed included diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, cardiovascular events, NLR‐NAR cancer, bone events, and non‐AIDS‐related infections. The variables for adjustment were age, sex, past AIDS, HIV transmission category, nadir CD4+ T‐cell count, antiretroviral therapy, HIV RNA, liver fibrosis, HCV genotype, and exposure to specific anti‐HIV drugs. Of the 1,625 patients included, 592 (36%) had a sustained viral response (SVR). After a median 5‐year follow‐up, SVR was found to be associated with a significant decrease in the hazard of diabetes mellitus (sHR, 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.35‐0.93; P = 0.024) and decline in the hazard of chronic renal failure close to the threshold of significance (sHR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.17‐1.09; P = 0.075). Conclusion: Our data suggest that eradication of HCV in coinfected patients is associated not only with a reduction in the frequency of death, HIV progression, and liver‐related events, but also with a reduced hazard of diabetes mellitus and possibly of chronic renal failure. These findings argue for the prescription of HCV therapy in coinfected patients regardless of fibrosis stage. (Hepatology 2017;66:344–356).

Abbreviations

- AIDS

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- cART

combination antiretroviral therapy

- CHC

chronic hepatitis C

- CI

confidence interval

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESRD

end‐stage renal disease

- GESIDA

Grupo de Estudio del Sida de la Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (AIDS Study Group of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology)

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HR

hazard ratio

- IFN

interferon

- IQR

interquartile range

- IR

insulin resistance

- IRRs

incidence rate ratios

- LDL

low‐density lipoprotein

- LT

liver transplantation

- NLR‐NAR

non‐liver‐related non‐AIDS‐related

- Peg‐IFN

pegylated interferon

- RBV

ribavirin

- SEIMC

Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology)

- sHR

subhazard rate

- SVR

sustained viral response

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

The liver is the key target of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection; however, patients with HCV infection may have extrahepatic manifestations that are directly or indirectly related to the virus and may account for substantial morbidity and mortality.1 The best documented of these complications is mixed cryoglobulinemia, although other conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, chronic renal failure, diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance (IR), B‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma, and neurocognitive dysfunction, have been associated with HCV infection.1, 2

In patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC), sustained viral response (SVR) following anti‐HCV therapy (i.e., eradication of HCV) significantly reduces progression of fibrosis and may reverse cirrhosis in some patients,3 although this process is limited by the extent of extracellular matrix cross‐linking and angiogenesis.4 More remarkably, eradication of HCV has been found to reduce liver decompensation and increase survival in cohorts of patients infected by HCV alone and patients coinfected by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).5, 6, 7 In a recent systematic review and meta‐analysis of the survival benefits of achieving SVR, viral clearance was found to be associated with a survival benefit in various HCV‐infected populations, and survival was higher in patients with cirrhosis and those coinfected with HIV.8

Many of the manifestations of HCV‐related mixed cryoglobulinemia can resolve following successful HCV treatment, although patients with significant renal or neural injury may not recover fully after eradication of HCV infection.9, 10 In the HCV‐monoinfected population, eradication of HCV following anti‐HCV therapy may reduce the risk of developing type II diabetes mellitus,11 renal and cardiovascular events,12, 13 and neurocognitive dysfunction.14

To the best of our knowledge, the effect of eradication of HCV on extrahepatic manifestations of HCV has not been systematically studied in HIV/HCV‐coinfected patients. The purpose of our study was to investigate the effect of sustained viral response in non‐liver‐related non–acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)‐related (NLR‐NAR) events in a large cohort of HIV/HCV–coinfected patients treated with interferon (IFN) plus ribavirin (RBV).

Patients and Methods

DESIGN AND PATIENT SELECTION

Patients were selected from the cohort of the “Grupo de Estudio del SIDA” (AIDS Study Group; GESIDA) of the “Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica” (Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology; SEIMC). This cohort was composed of patients who were naïve to anti‐HCV therapy and who were treated with IFN and RBV. The cohort was established in 2003 to follow HIV/HCV–coinfected patients who started treatment with these drugs between January 2000 and January 2008 at 19 institutions in Spain. The primary objective of this cohort study was to determine the effect of response to IFN and RBV on long‐term clinical outcomes, including liver‐related complications, AIDS‐related conditions, and mortality. The local ethics committees waived the requirement for written informed consent, because the study was based on anonymous routine clinical data intended for scientific publication.

Anti‐HCV therapy in Spain is provided by hospital pharmacies and is covered by the National Health System. The decision to administer IFN and RBV to coinfected patients was taken by infectious diseases physicians at each institution according to national and international guidelines. The eligibility criteria for IFN and RBV therapy included the absence of previous hepatic decompensation, severe concurrent medical conditions (such as poorly controlled hypertension, heart failure, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and severely reduced renal function), CD4+ T‐cell count >200 cells/μL, stable antiretroviral therapy or no need for antiretroviral therapy, the absence of active opportunistic infections, and a ≥6‐month period of abstinence from heroin and cocaine in patients with a history of injection drug use. Patients were advised not to consume alcohol. Anti‐HCV therapy was stopped in all patients with detectable HCV RNA at week 24 of treatment. Since 2002, anti‐HCV therapy was also stopped in patients with detectable HCV RNA at week 12 of treatment and a reduction of <2 log IU/mL in HCV RNA.

INVESTIGATIONS

All the data were entered directly into a shared database (created in 2003) by trained personnel at each institution using an online application that satisfied local requirements of data confidentiality. This database included all demographic, clinical, virological (HIV and HCV), and laboratory data. The database was modified in the first semester of 2014 to include variables related to NLR‐NAR events during follow‐up (see below), which were registered between June and September 2014. All centers were monitored between October 2014 and April 2015 to verify that all the information in the database was consistent with the patient's medical history.

For each patient, we extracted the following data from the central database: age; sex; HIV transmission category; previous AIDS‐defining conditions; baseline and nadir CD4+ T‐cell counts; and baseline HIV viral load. We also recorded information about combination antiretroviral therapy, including type, date of initiation, and whether it was maintained or changed during therapy. Information related to HCV infection included genotype, HCV‐RNA levels, and estimated year of HCV infection (assumed to be the first year needles were unsafely shared in the case of injection drug users). Duration of HCV infection was unknown for patients infected through sexual contact. Patients were asked about their current alcohol intake. A high intake of alcohol was defined as the consumption of more than 50 g of alcohol per day for at least 12 months.

Local pathologists scored liver biopsy samples following the criteria established by the METAVIR Cooperative Study Group15 as follows: F0, no fibrosis; F1, portal fibrosis; F2, periportal fibrosis or rare portal‐portal septa; F3, fibrous septa with architectural distortion and no obvious cirrhosis (bridging fibrosis); and F4, definite cirrhosis. Staging of liver fibrosis was also estimated at baseline using the FIB‐4 index16; advanced fibrosis was defined as a, FIB‐4 value ≥3.25.

Patients with an undetectable serum HCV‐RNA level 24 weeks after discontinuation of therapy were classified as having an SVR; patients not fulfilling the criteria for an SVR, including those who had a relapse after achieving an end‐of‐treatment response, were classified as nonresponders. Safety was assessed by laboratory tests and evaluation of adverse clinical events during therapy.

FOLLOW‐UP

Completion of treatment was followed by active monitoring (semiannually until July 2010 and annually thereafter) to analyze clinical and laboratory parameters, including survival, presence of liver decompensation, antiretroviral therapy, CD4+ T‐cell count, HIV viral load, HCV RNA, and assessment of liver fibrosis. The length of the study was calculated from the date IFN plus RBV was stopped to death or the last follow‐up visit. The administrative censoring date was May 31, 2014.

CLINICAL ENDPOINTS

We assessed the following incident endpoints: liver‐related events; AIDS‐related events; NLR‐NAR events; and mortality.

Liver‐related events included ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), variceal bleeding, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and liver transplantation (LT). Ascites was confirmed by paracentesis and/or ultrasound. HE was established on clinical grounds after the reasonable exclusion of HIV‐associated encephalopathy based on clinical and laboratory parameters (i.e., CD4+ T‐cell counts, HIV viral load, and neuroimaging techniques). The source of gastroesophageal bleeding was confirmed by endoscopy whenever possible. For patients who had more than one event, only the first was included in the analyses of the association between sustained viral response and “any event.”

AIDS‐related events were defined as the occurrence of any new AIDS‐defining conditions.17

NLR‐NAR events included cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, peripheral artery disease, heart failure, ruptured aortic aneurysm, and mesenteric artery ischemia), renal events (chronic renal failure, dialysis, and renal transplantation), bone events (bone fractures and avascular bone necrosis), diabetes mellitus, NLR‐NAR cancer (biopsy confirmed), and non‐AIDS‐related infections. As mentioned above, incident NLR‐NAR events were collected retrospectively. For this purpose, all centers were provided with a structured electronic reporting form containing the list of NLR‐NAR events and the precise definition of each of them based on a modified version of the Cohort of the Spanish AIDS Research Network criteria19 (Supporting Tables S1 and S2).

All the information related to death (death reports, autopsy reports [if available], and standard forms) was reviewed by J.B. and J.G.G. Both authors were blind to the category of treatment response and classified deaths in accord with the opinion of the attending clinician as follows: (1) liver‐related death, when the train of events that ended in death was caused by liver decompensation or HCC; (2) AIDS‐related death, when death was directly related to an AIDS‐defining condition; and (3) NLR‐NAR deaths.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Differences between groups were analyzed using the chi‐square test, t test, or Mann‐Whitney U test, as appropriate. Normality was analyzed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. We calculated the frequency and incidence rates of the different endpoints. The Pearson chi‐square test was used to assess differences between the frequency of events between responders and nonresponders. Unadjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for events in nonresponders versus responders were estimated using Poisson regression. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to compare the overall hazard of death between responders and nonresponders. Univariate and multivariate Fine and Gray regression analyses were performed as an alternative to Cox regression for comparison of the subhazard of survival data in the presence of competing risks. The dependent variables were cause‐specific deaths, liver‐related events, AIDS‐related events, and NLR‐NAR events. When factors associated with each cause‐specific death were analyzed, the competing risk was the other causes of death as a whole. When factors associated with events were analyzed, the competing risk was overall death. In the multivariate analyses, the variables for adjustment were age, sex, previous AIDS‐defining conditions (yes vs. no), HIV transmission category (injection drug users vs. non–injection drug users), nadir CD4+ T‐cell count, combination antiretroviral therapy (yes vs. no), undetectable HIV‐RNA at baseline (yes vs. no), FIB ≥3.25 (yes vs. no), genotype (3 vs. other genotypes), and cumulative exposure to selected antiretroviral drugs. We adjusted for FIB‐4 instead of biopsy stage (METAVIR) in our multivariate analysis because we previously showed, in this same cohort, that FIB‐4 outperforms liver biopsy in the assessment of prognosis (death and liver‐related events) in HIV/HCV–coinfected patients.18 Patients who had diabetes mellitus or chronic renal failure according to our definitions at baseline were excluded from the analysis for these particular NLR‐NAR events.

Because some patients experienced reinfections and several patients underwent retreatment with IFN plus RBV, we carried out various sensitivity analyses: (1) the primary analysis, in which patients who achieved an SVR with retreatment (after failure or after relapse) were included in the SVR group; (2) the second analysis, in which follow‐up of retreated patients was censored on the same day of initiation of the second course of IFN plus RBV; (3) the third analysis, in which patients who were retreated were excluded from the analysis; and (4) the fourth analysis, in which treatment response status was considered a time‐dependent variable, that is, some patients could be considered both responders and nonresponders during follow‐up. We also performed two sensitivity analyses according to the classification of liver fibrosis in addition to the primary analysis, in which fibrosis was categorized as FIB ≥3.25 versus FIB‐4 <3.25; (1) in the first analysis—limited to patients with liver‐biopsy data—fibrosis was categorized as F0‐F2 versus F3‐F4; and (2) in the second analysis, fibrosis was categorized as FIB‐4 <3.25 or F0‐F2 versus FIB ≥3.25 or F3‐F4.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 21.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The R package, cmprsk (version 2.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing), was used to plot the cumulative incidence curves and conduct competing risks regression analysis. The cmprsk package can be downloaded from the Comprehensive R Archive Network (http://cran.r‐project.org) and run within R.

Results

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

Data from the 1,625 patients who started treatment between January 2000 and January 2008 were included in the database. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. In brief, 75.0% were men, the median age was 40 years, 22.8% had previous AIDS‐defining conditions, 1,366 (84.1%) were on combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), the median baseline CD4 cell count was 527 cells/mm3, 69.4% had an undetectable HIV viral load, 62.4% were infected with genotypes 1 or 4, and 60.6% had an HCV RNA ≥500,000 IU/mL. Baseline liver biopsy was performed in 1,154 patients, of whom 445 (38.6%) had bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis. At baseline, 77 (4.7%) patients reported a high intake of alcohol, 47 (2.9%) had diabetes mellitus, and 4 (0.2%) had chronic renal failure.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1,625 HIV/HCV–Coinfected Patients Stratified According to Response to IFN Plus RBV

| Characteristic |

No SVR (n = 997) |

SVR (n = 628) |

Total (N = 1,625) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex, no. (%) | 753 (75.5) | 466 (74.2) | 1,219 (75.0) |

| Age, years, median (IQR) (baseline) | 40 (37‐43) | 40 (37‐43) | 40 (37‐43) |

| BMI (n = 1,332), median (IQR) | 23.1 (21.1‐25.3) | 23.0 (21.3‐25.6) | 23.1 (21.2‐25.4) |

| Follow‐up months, median (IQR) | 65 (42‐85) | 65 (43‐86) | 65 (43‐85) |

| Past injection drug use, no. (%) | 802 (80.4) | 510 (81.2) | 1,312 (80.7) |

| CDC disease category C, No. (%)a | 245 (24.6) | 125 (19.9)c | 370 (22.8) |

| CD4+, nadir, cells/mm3, median (IQR) | 200 (100‐313) | 212 (113‐333) | 204 (106‐322) |

| cART during anti‐HCV treatment, no. (%) | 848 (85.1) | 518 (82.5) | 1,366 (84.1) |

| CD4+, baseline, cells/mm3, median (IQR) | 515 (374‐718) | 536 (404‐729) | 527 (391‐724) |

| Undetectable HIV‐RNA load at baseline, no. (%) | 667 (66.9) | 460 (73.2)c | 1,127 (69.4) |

| Duration of HCV infection, years, median (IQR) | 18 (13‐22) | 19 (15‐22) | 19 (13‐22) |

| HCV genotype, no. (%) | |||

| 1 | 581 (58.3) | 224 (35.7)c | 805 (49.5) |

| 2 | 13 (1.3) | 24 (3.8)c | 37 (2.3) |

| 3 | 214 (21.5) | 332 (52.9)c | 546 (33.6) |

| 4 | 170 (17.1) | 40 (6.4)c | 210 (12.9) |

| Unknown | 10 (1) | 5 (0.8) | 15 (0.9) |

| HCV RNA, no. (%) | |||

| <500,000 IU/mL | 282 (28.3) | 258 (41.1)c | 540 (33.2) |

| ≥500,000 IU/mL | 644 (64.6) | 340 (54.1)c | 984 (60.6) |

| Unknown | 71 (7.1) | 30 (4.8) | 101 (6.2) |

| HBsAg positivity, no. (%) | 39 (3.9) | 16 (2.5) | 55 (3.4) |

| METAVIR fibrosis score, no. (%) | |||

| F0 | 44 (4.4) | 31 (4.9) | 75 (4.6) |

| F1 | 163 (16.3) | 132 (21)c | 295 (18.2) |

| F2 | 200 (20.1) | 139 (22.1) | 339 (20.9) |

| F3 | 215 (21.6) | 93 (14.8)c | 308 (19.0) |

| F4 | 109 (10.9) | 28 (4.5)c | 137 (8.4) |

| Unknown | 266 (26.7) | 205 (32.6)c | 471 (29.0) |

| FIB‐4 score, no. (%) | |||

| <3.25 | 671 (67.3) | 486 (77.4)c | 1,157 (71.2) |

| ≥3.25 | 207 (20.8) | 71 (11.3)c | 278 (17.1) |

| Unknown | 119 (11.9) | 71 (11.3) | 190 (11.7) |

| Current alcohol intake >50 g/day, no. (%) | 58 (5.8) | 19 (3)c | 77 (4.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 39 (3.9) | 8 (1.3)c | 47 (2.9) |

| Chronic renal failureb | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) |

A, asymptomatic acute HIV or persistent generalized lymphadenopathy; B, symptomatic non‐C conditions; C, AIDS‐defining conditions.

Confirmed eGFR <60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 at baseline.

P < 0.05 compared to the no SVR group.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

During the study period, no significant differences were found between responders and nonresponders for qualitative or cumulative exposure to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, a potentially nephrotoxic drug.19 However, significant differences were found between responders and nonresponders in qualitative and/or cumulative exposure to didanosine, abacavir, indinavir, and lopinavir, all of which have been associated with cardiovascular disease20 (Supporting Table S3).

TREATMENT RESPONSE

A total of 791 (48.7%) patients were treated with pegylated interferon (Peg‐IFN) α2a plus RBV, 615 (37.8%) were treated with Peg‐IFN α2b plus ribavirin, and 219 (13.5%) were treated with the standard IFN α plus RBV regimen (three times weekly). The initial treatment response was categorized as SVR in 592 (36%) patients and as no response in 1,033 (64%). During follow‐up, 6 (1%) of 592 responders developed HCV reinfection a median of 49 months after discontinuing anti‐HCV therapy (minimum, 22 months; maximum, 87 months). A total of 198 patients were retreated during follow‐up: 192 patients whose first course of anti‐HCV therapy failed and the 6 patients who experienced reinfections. A total of 42 retreated patients achieved SVR, including 1 of the 6 reinfected patients. For the purpose of the primary analysis, there were 628 responders and 997 nonresponders.

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

The median (interquartile range; IQR) follow‐up from the date IFN plus RBV was stopped for nonresponders and responders was 65 (42‐85) and 65 (43‐86) months, respectively. Loss to follow‐up was recorded in 162 nonresponders (16.2%) and 74 responders (11.8%; P = 0.013).

A detailed description of incident NLR‐NAR events during follow‐up is shown in Table 2. By order of frequency, these were cancer (n = 100 [6.2%]), diabetes mellitus (n = 95 [6.0%]), cardiovascular events (n = 91 [5.6%]), non‐AIDS‐related infections (n = 81 [5.0%]), bone‐related events (n = 57 [3.5%]), and renal events (n = 33 [2.0%]).

Table 2.

Detailed Description of NLR‐NAR Events During Follow‐up in HIV/HCV–Coinfected Patients Categorized According to Response to Therapy With IFN Plus RBV

| Event |

No SVR (n = 997) |

SVR (n = 628) |

Total (N = 1,625) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer (non‐AIDS non‐liver‐related) | 67 (6.7) | 33 (5.3) | 100 (6.2) |

| Lung | 7 (0.7) | 6 (1.0) | 13 (0.8) |

| Anus | 7 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) | 9 (0.6) |

| Head and neck | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) | 8 (0.5) |

| Vagina/vulva | 6 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (0.4) |

| Colorectal | 6 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 6 (0.4) |

| Breast | 5 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.3) |

| Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 5 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.3) |

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) |

| Brain | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.2) |

| Sarcoma | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) |

| Penis | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) |

| Esophagus | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) |

| Stomach | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.1) |

| Other hematological | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) |

| Prostate | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) |

| Other | 14 (1.4) | 12 (1.9) | 26 (1.6) |

| Diabetes mellitusa | 72 (7.5)c | 23 (3.7)c | 95 (6.0) |

| Cardiovascular events | 52 (5.2) | 39 (6.2) | 91 (5.6) |

| Coronary acute myocardial infarction | 19 (1.9) | 23 (3.7) | 42 (2.6) |

| Coronary angina | 8 (0.8) | 3 (0.5) | 11 (0.7) |

| Cerebrovascular transient ischemic attack | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.6) | 6 (0.4) |

| Cerebrovascular reversible ischemic deficit | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.1) |

| Cerebrovascular established stroke | 3 (0.3) | 4 (0.6) | 7 (0.4) |

| Cerebrovascular asymptomatic cerebrovascular disease | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 7 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) | 9 (0.6) |

| Congestive heart failure | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.3) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 5 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 6 (0.4) |

| Mesenteric ischemia | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Aortic dissection | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Non‐AIDS‐related sepsis requiring hospital admission | 62 (6.2)c | 19 (3.0)c | 81 (5.0) |

| Bone‐related events | 33 (3.3) | 24 (3.8) | 57 (3.5) |

| Large bone fracture | 23 (2.3) | 19 (3.0) | 42 (2.6) |

| Avascular necrosis of bone | 5 (0.5) | 5 (0.8) | 10 (0.6) |

| Vertebral fracture | 5 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.3) |

| Renal eventsb | 27 (2.7)c | 6 (1.0)c | 33 (2.0) |

| Chronic renal failure not requiring dialysis | 24 (2.4)c | 5 (0.8)c | 29 (1.8) |

| Chronic renal failure requiring dialysis | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) |

Including 958 non‐SVR and 620 SVR patients (patients with baseline diabetes mellitus were excluded).

Including 994 non‐SVR and 627 SVR patients (patients with chronic renal failure at baseline were excluded).

P < 0.05.

The frequencies and rates of events during follow‐up stratified by response to IFN plus RBV are shown in Table 3. The rates of overall death, liver‐related death, new AIDS‐defining conditions, and all types of liver‐related events (decompensation, HCC, and LT) were significantly higher in nonresponders than in responders. As for NLR‐NAR events, we found that the rates of diabetes mellitus, non‐AIDS‐related infections, and renal events were significantly higher in nonresponders than in responders. However, the rates of NLR‐NAR cancers, cardiovascular events, and bone events were not significantly different between responders and nonresponders.

Table 3.

Frequency and Rate of Events During Follow‐up in 1,625 HIV/HCV–Coinfected Patients Categorized According to Response to IFN Plus RBV Therapy

| Frequency, No. (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No SVR | SVR | Rate/100 Person‐Years (95% CI) | |||||

| Event | (N = 997) | (N = 628) | P1 | No SVR | SVR | IRR (95% CI) | P2 |

| Lost to follow‐up | 162 (16.2) | 74 (11.8) | 0.013 | 3.19 (2.72‐3.72) | 2.33 (1.83‐2.92) | 1.37 (0.97‐1.7) | 0.075 |

| Overall mortality | 145 (14.5) | 30 (4.8) | <0.001 | 2.75 (2.32‐3.23) | 0.93 (0.63‐1.33) | 2.95 (1.99‐4.36) | <0.001 |

| Liver‐related | 83 (8.3) | 6 (1.0) | <0.001 | 1.57 (1.25‐1.95) | 0.19 (0.07‐0.41) | 8.43 (3.68‐19.3) | <0.001 |

| Non‐liver‐related | 62 (6.2) | 24 (3.8) | 0.036 | 1.17 (0.90‐1.50) | 0.75 (0.48‐1.11) | 1.57 (0.98‐2.52) | 0.059 |

| AIDS‐related | 8 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 0.224 | 0.15 (0.07‐0.30) | 0.06 (0.01‐0.22) | 2.44 (0.52‐11.5) | 0.260 |

| Non‐liver‐related non‐AIDS‐related | 54 (5.4) | 22 (3.5) | 0.075 | 1.02 (0.77‐1.33) | 0.68 (0.43‐1.03) | 1.50 (0.91‐2.46) | 0.111 |

| CDC category C disease | 43 (4.3) | 9 (1.4) | 0.001 | 0.81 (0.59‐1.10) | 0.28 (0.13‐0.53) | 2.91 (1.54‐6.97) | 0.002 |

| Liver decompensation | 123 (12.3) | 7 (1.1) | <0.001 | 2.44 (2.03‐2.91) | 0.22 (0.09‐0.45) | 11.20 (5.14‐23.6) | <0.001 |

| HCC | 29 (2.9) | 3 (0.5) | 0.001 | 0.55 (0.37‐0.79) | 0.09 (0.02‐0.27) | 5.92 (2.04‐36.0) | 0.003 |

| LT, no. (%) | 16 (1.6) | 1 (0.2) | 0.005 | 0.30 (0.17‐0.49) | 0.03 (0‐0.17) | 9.80 (1.30‐73.9) | 0.027 |

| NLR‐NAR events | |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 72/958 (7.5) | 23/620 (3.7) | 0.002 | 1.45 (1.13‐1.82) | 0.73 (0.46‐1.09) | 1.99 (1.24‐3.18) | 0.004 |

| NLR‐NAR cancer | 67 (6.7) | 33 (5.3) | 0.231 | 1.28 (0.99‐1.63) | 1.04 (0.72‐1.46) | 1.23 (0.81‐1.87) | 0.329 |

| Cardiovascular events | 52 (5.2) | 39 (6.2) | 0.396 | 0.99 (0.74‐1.30) | 1.24 (0.88‐1.69) | 0.80 (0.53‐1.22) | 0.302 |

| NAR infections | 62 (6.2) | 19 (3.0) | 0.004 | 1.19 (0.91‐1.52) | 0.59 (0.36‐0.93) | 2.01 (1.20‐3.34) | 0.008 |

| Bone events | 33 (3.3) | 24 (3.8) | 0.585 | 0.63 (0.44‐0.89) | 0.75 (0.48‐1.12) | 0.84 (0.48‐1.38) | 0.447 |

| Renal events | 27/994 (2.7) | 6/627 (0.1) | 0.015 | 0.51 (0.34‐0.75) | 0.19 (0.07‐0.41) | 2.74 (1.13‐6.65) | 0.025 |

P 1 = Pearson chi2 test; P2 = Poisson regression.

*Median follow‐up times in months (IQR) for no‐SVR and SVR were 59.3 (40.6‐79.2) and 59.5 (42.8‐81.8).

Abbreviation: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The results of the univariate and multivariate proportional hazards regression analyses of factors associated with clinical outcomes are shown in Table 4. In comparison with no response, SVR was associated with a statistically significant reduced adjusted hazard of overall death (hazard ratio [HR] and 95% CI, 0.36 [0.24‐0.54]; P < 0.001), liver‐related death (subhazard ratio [sHR] and 95% CI, 0.13 [0.06‐0.28]; P < 0.001), new AIDS‐defining events (sHR [95% CI], 0.37 [0.17‐0.79]; P = 0.010), liver decompensation (sHR [95%CI], 0.10 [0.05 ‐ 0.21]; P < 0.001), HCC (sHR [95% CI], 0.13 [0.03‐0.50]; P = 0.003), and LT (sHR [95% CI], 0.12 [0.02‐0.78]; P = 0.027). As for NLR‐NAR events, SVR was independently associated with a statistically significant reduced hazard of diabetes mellitus (sHR [95% CI], 0.57 [0.35‐0.93]; P = 0.024), with a reduced hazard of renal events close to the threshold of significance (sHR [95% CI], 0.42 [0.17‐1.09]; P = 0.074), and with a higher hazard of cardiovascular events also close to the threshold of significance (sHR [95% CI], 1.57 [0.99‐2.50]; P = 0.056). The results of the primary analysis were confirmed in the sensitivity analyses based on the definitions of treatment response, although in the third subanalysis, the reduced adjusted hazard of renal events following eradication of HCV was statistically significant (Supporting Table S4). The results of the primary analysis also remained unchanged after the different sensitivity analyses based on the different definitions of advanced fibrosis (data not shown).

Table 4.

Crude and Adjusted Hazards for Events During Follow‐up for 997 Nonresponders to IFN plus RBV Compared With 628 Responders

| Univariate Analysisa | Multivariate Analysisa, b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Overall deaths | 0.35 (0.24‐0.52) | <0.001 | 0.36 (0.24‐0.54) | <0.001 |

| sHR (95% CI) | P Value | sHR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Cause‐specific deaths | ||||

| Liver‐related deaths | 0.12 (0.05‐0.28) | <0.001 | 0.13 (0.06‐0.28) | <0.001 |

| Non‐liver‐related deaths | 0.69 (0.43‐1.1) | 0.119 | 0.73 (0.44‐1.20) | 0.214 |

| AIDS‐related deaths | 0.45 (0.09‐2.22) | 0.325 | 0.37 (0.09‐1.43) | 0.148 |

| NLR‐NAR deaths | 0.73 (0.44‐1.19) | 0.204 | 0.79 (0.47‐1.35) | 0.388 |

| New AIDS‐defining events | 0.34 (0.16‐0.72) | 0.004 | 0.37 (0.17‐0.79) | 0.010 |

| Liver‐related events | ||||

| Liver decompensation | 0.09 (0.04‐0.2) | <0.001 | 0.10 (0.05‐0.21) | <0.001 |

| HCC | 0.12 (0.03‐0.5) | 0.004 | 0.13 (0.03‐0.50) | 0.003 |

| LT | 0.10 (0.01‐0.77) | 0.027 | 0.12 (0.02‐0.78) | 0.027 |

| NLR‐NAR events | ||||

| Diabetes mellitusc | 0.54 (0.34‐0.87) | 0.011 | 0.57 (0.35‐0.93) | 0.024 |

| NLR‐NAR cancer | 0.91 (0.6‐1.38) | 0.650 | 0.91 (0.58‐1.45) | 0.703 |

| Cardiovascular events | 1.41 (0.93‐2.13) | 0.105 | 1.57 (0.99‐2.50) | 0.056 |

| NAR infections | 0.55 (0.33‐0.92) | 0.024 | 0.65 (0.37‐1.14) | 0.131 |

| Bone events | 1.39 (0.82‐2.35) | 0.225 | 1.28 (0.69‐2.38) | 0.433 |

| Renal eventsc | 0.41 (0.17‐0.99) | 0.049 | 0.43 (0.17‐1.09) | 0.075 |

Cox regression analysis was performed to compare the HR of overall death between responders and nonresponders. Fine and Gray regression analysis was performed to compare the HR of events in the presence of competing risks.

Adjusted for age, sex, previous AIDS‐defining conditions (yes vs. no), HIV transmission category (injection drug users vs. non–injection drug users), nadir CD4+ cell count, cART (yes vs. no), undetectable HIV RNA at baseline (yes vs. no), FIB4 ≥3.25 (yes vs. no), genotype (3 vs. other genotypes), and exposure to abacavir, didanosine, indinavir, and lopinavir: lower than or equal to the median cumulative exposure in years versus higher than the median cumulative exposure.

Excluding 47 and 4 patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure at baseline, respectively.

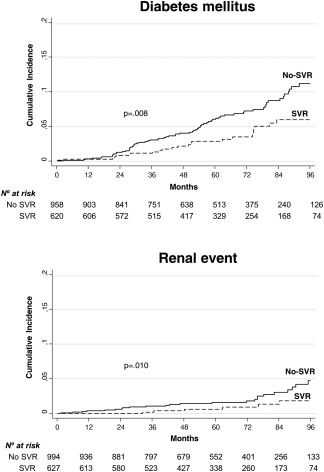

The cumulative probabilities of diabetes mellitus and renal events in responders and nonresponders are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Cumulative probabilities of renal events and diabetes mellitus in responders and non‐responders. Responders and non‐responders were compared using Gray's test.

Discussion

We evaluated the clinical course of 1,625 HIV/HCV–coinfected patients who were followed up for a median of 5 years after the end of treatment with IFN plus RBV, with the primary objective of evaluating the effect of treatment response on incident NLR‐NAR events. We found that during follow‐up, the incidence rates of diabetes mellitus, renal events, and non‐AIDS‐related infections were significantly lower in responders than in nonresponders. However, no significant differences were found between the groups in the rates of NLR‐NAR cancers, cardiovascular events, and bone events. When we carried out regression analysis after adjusting for clinically significant covariates and considering death as a competitive risk, we found that SVR was associated with a significant decrease in the hazard of diabetes mellitus. However, the decrease in the hazard of renal events almost reached statistical significance. In agreement with previous reports from this cohort, we found that treatment response was associated with a decreased hazard of overall and liver‐related death, all types of liver‐related events, and new AIDS‐related conditions.7, 21

Our finding that treatment response in HIV/HCV–coinfected patients was associated with a significant decrease in the hazard of diabetes mellitus lends further support to the causative role of HCV infection in IR and type 2 diabetes (T2D)22 and agrees with findings from previous studies in which SVR caused a reduction in the risk of T2D in HCV‐monoinfected patients.11 It is also worth mentioning that IR and diabetes are associated with progression of liver disease, hepatic decompensation, and death in patients with chronic HCV23, 24, 25, 26 and with HCC in patients with HCV‐related cirrhosis with or without HIV infection.27, 28 For these reasons, patients with CHC and IR or T2D might benefit from antiviral therapy irrespective of their stage of fibrosis.29

HCV infection has been associated with an increased risk of end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) in HCV‐monoinfected individuals30, 31 and HIV/HCV–coinfected individuals.32, 33 HCV infection has also been found to increase the mortality of patients with ESRD.34 In addition, antiviral treatment for HCV has been associated with a lower risk of ESRD in large, prospective cohorts in HCV‐monoinfected individuals.12, 13 We found a significantly higher incidence of renal events in nonresponders than in responders. However, with the stricter multivariate competing risk regression analyses, the lower hazard of chronic renal failure in responders than in nonresponders did not reach the conventional threshold for significance (P = 0.075). The clinical and public health repercussions of this finding are relevant because the risk of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization increases proportionally with reductions in estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFRs) below 60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2.35

In our study, NLR‐NAR cancer was the most common NLR‐NAR event during follow‐up; however, the hazard of this event was not found to be modified by eradication of HCV. Despite advances in HIV therapy, cancer rates are still higher among HIV‐infected individuals than among matched non‐HIV‐infected individuals,36 probably owing to the high prevalence of traditional cancer risk factors, coinfection with other oncogenic viruses, and associated immunodeficiency among HIV‐infected individuals.37 In addition, non‐AIDS‐related cancer is currently the leading non‐AIDS cause of death among people with HIV in high‐income settings.38 For all the above reasons, evidence‐based cancer screening must be considered an essential component in the care of HIV‐infected individuals.

Intriguingly, although the crude incidence of cardiovascular events was not significantly different between responders and nonresponders, competing risk regression analysis showed the adjusted hazard of cardiovascular events to be higher in responders than in nonresponders, although, once again, on the very threshold of statistical significance (P = 0.056). This finding contrasts with those other studies in which HCV clearance following anti‐HCV therapy has been found to reduce the risk of stroke.39, 40 The association between HCV infection and cardiovascular events is a contentious issue. Several observational studies have found that in the general population, HCV is an independent factor associated with coronary artery disease,41, 42, 43, 44, 45 stroke,39, 46, 47 and peripheral artery disease.48 HCV infection has also been found to increase the likelihood of cardiovascular disease among HIV‐infected individuals.49, 50 However, other researchers have not found an association between HCV infection and angiographic coronary artery disease51, 52 or myocardial infarction.53 Meta‐analyses have demonstrated an increased risk of cardiovascular events associated with HCV infection in some patients,54, 55 but not in others.56 It is important to note that HCV infection has opposing effects on the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. On the one hand, HCV induces an alteration in markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction that could potentially stimulate atherogenesis.57, 58, 59 On the other hand, HCV infection is associated with lower total cholesterol and low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels,60, 61 probably owing to increased deposition of lipids in hepatocytes, where the lipids are used to promote HCV replication and secretion of lipoviroparticles. Also noteworthy are the different effects of eradication of HCV on atherogenesis, namely, reversion of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction62 and rebound of LDL and total cholesterol to levels associated with increased risk of coronary disease.60, 63 The above findings indicate that further work is needed to assess the effects of eradication of HCV on preclinical atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events.

Both injection drug use and liver cirrhosis can contribute to bacterial infections among HCV‐infected individuals. As for liver cirrhosis, the only identified factor for bacterial infections is advanced liver disease.64 In the cART era, HCV infection has been shown to predispose to severe bacterial infections associated with hospitalization or death in HIV‐infected individuals.65 However, we did not find a significant association between response to anti‐HCV treatment and the hazard of non‐AIDS‐related infections.

Chronic HCV infection is associated with low bone mineral density, even in the absence of cirrhosis66; in coinfected patients, both HIV infection and HCV infection have been found to reduce bone mineral density through different pathophysiological mechanisms.67 Furthermore, HCV has been found to increase the risk of osteoporotic fractures among HIV‐infected patients, a risk that is explained, only in part, by the severity of liver disease.68 We did not find an association between eradication of HCV and the hazard of bone fractures; however, it has yet to be determined whether successful treatment of HCV will significantly improve bone mineral density in HIV/HCV–coinfected patients.

The main limitation of our study is that its design was not entirely prospective. However, we believe that its characteristics make it unlikely that the results differ considerably from those that would have been obtained in an entirely prospective study: patients were followed by the same infectious diseases physicians in the same reference hospitals throughout the course of the disease, with standard clinical and laboratory parameters assessed at least every 6 months. In addition, the frequency of loss to follow‐up was higher among nonresponders than among responders. However, we believe that the potential bias caused by this difference would tend to minimize the frequency and rates of events among nonresponders rather than increase them. Our study is also limited by the lack of information about pneumococcal vaccination, smoking, alcohol and drug use during follow‐up, and cardiovascular risk factors; therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that differences in these variables could have affected outcome. The strengths of our study include the high number of patients included and the long follow‐up period. We also emphasize the use of multivariate Fine and Gray regression as an alternative to Cox regression for survival data in the presence of competing risks and the performance of sensitivity analyses that confirmed the findings of the primary analysis. Finally, in our study, all the information in the database was monitored to verify that it was consistent with the patient's medical records.

Although the study design precludes determination of causality, our results suggest that eradication of HCV in coinfected patients is associated not only with a reduction in overall death, liver‐related death, new AIDS‐related events, and all types of liver‐related events, but also with a statistically significant reduced hazard of diabetes mellitus and a decline in the hazard of chronic renal failure very close to the threshold of significance. These findings argue for the prescription of HCV therapy regardless of liver fibrosis stage in coinfected patients.

Author names in bold designate shared co‐first authorship.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29071/suppinfo.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas O'Boyle for writing assistance during the preparation of the manuscript.

THE GESIDA HIV/HCV COHORT STUDY GROUP

Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid: A. Carrero, P. Miralles, J.C. López, F. Parras, B. Padilla, T. Aldamiz‐Echevarría, F. Tejerina, C. Díez, L. Pérez‐Latorre, I. Gutiérrez, M. Ramírez, S. Carretero, J.M .Bellón, and J. Berenguer. Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid: E. Rodríguez‐Castellano, J. Alvarez‐Pellicer, J.R. Arribas, M.L. Montes, I. Bernardino, J.F. Pascual, F. Zamora, V. Hontañón, J.M. Peña, F. Arnalich, M. Díaz, and J. González‐García. Hospital Donostia, San Sebastián: M.J. Bustinduy, J.A. Iribarren, F. Rodríguez‐Arrondo, and M.A. Von‐Wichmann. Hospital Universitari La Fe, Valencia: M. Montero, M. Blanes, S. Cuellar, J. Lacruz, M. Salavert, and J. López‐Aldeguer. Hospital Clinic, Barcelona: P. Callau, J.M. Miró, J.M. Gatell, and J. Mallolas. Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valencia: A. Ferrer and M.J. Galindo. Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona: E. Van den Eynde, M. Pérez, E. Ribera, and M. Crespo. Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid: J. Vergas and M.J. Téllez. Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid: J.L. Casado, F. Dronda, A. Moreno, M.J. Pérez‐Elías, M.A. Sanfrutos, S. Moreno, and C. Quereda. Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona: A. Jou and C. Tural. Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares: A. Arranz, E. Casas, J. de Miguel, S. Schroeder, and J. Sanz. Hospital Universitario de Móstoles, Móstoles: E. Condés and C. Barros. Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Madrid: J. Sanz and I. Santos. Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid: A. Hernando, V. Rodríguez, R. Rubio, and F. Pulido. Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona: P. Domingo and J.M. Guardiola. Hospital General Universitario, Valencia: L. Ortiz and E. Ortega. Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa, Leganés: R. Torres, M. Cervero, and J.J. Jusdado. Hospital General Universitario de Guadalajara, Guadalajara: M. Rodríguez‐Zapata. Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Getafe: G. Pérez and G. Gaspar. Fundación SEIMC‐GESIDA, Madrid: M. Yllescas, P. Crespo, E. Aznar, and H. Esteban.

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Gaspar consults for Gilead, ViiV, Merck, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Janssen. Dr. Gonzalez‐Garcia advises for, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from Gilead, AbbVie, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and MSD. He is on the speakers' bureau for and received grants from ViiV. Dr. Mallolas consults for, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from MSD, Janssen, and Gilead. Dr. Berenguer is on the speakers' bureau for and received grants from AbbVie, Gilead, MSD, and ViiV. He is on the speakers' bureau for Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Janssen.

Supported by grants from Fondo de Investigacion de Sanidad en España (FIS) (Spanish Health Research Funds) (Refs. EC07/90734, PI11/01556, and EC11/241) and by Red de Investigación en SIDA (AIDS Research Network) (RIS) Ref RD16/0025/0017. Dr. Juan Berenguer is an investigator of the Programa de Intensificación de la Actividad Investigadora en el Sistema Nacional de Salud (I3SNS) (Refs.).

REFERENCES

- 1. Cacoub P, Gragnani L, Comarmond C, Zignego AL. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Dig Liver Dis 2014;46(Suppl 5):S165‐S173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Soriano V, Berenguer J. Extrahepatic comorbidities associated with hepatitis C virus in HIV‐infected patients. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2015;10:309‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Poynard T, McHutchison J, Manns M, Trepo C, Lindsay K, Goodman Z, et al. Impact of pegylated interferon alfa‐2b and ribavirin on liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1303‐1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramachandran P, Iredale JP, Fallowfield JA. Resolution of liver fibrosis: basic mechanisms and clinical relevance. Semin Liver Dis 2015;35:119‐131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Veldt BJ, Heathcote EJ, Wedemeyer H, Reichen J, Hofmann WP, Zeuzem S, et al. Sustained virologic response and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:677‐684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, Wedemeyer H, Dufour JF, Lammert F, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all‐cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA 2012;308:2584‐2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berenguer J, Alvarez‐Pellicer J, Martin PM, Lopez‐Aldeguer J, Von‐Wichmann MA, Quereda C, et al. Sustained virological response to interferon plus ribavirin reduces liver‐related complications and mortality in patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2009;50:407‐413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Simmons B, Saleem J, Heath K, Cooke GS, Hill A. Long‐term treatment outcomes of patients infected with hepatitis C virus: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the survival benefit of achieving a sustained virological response. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:730‐740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shiffman ML, Benhamou Y. Cure of HCV related liver disease. Liver Int 2015;35(Suppl 1):71‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sise ME, Bloom AK, Wisocky J, Lin MV, Gustafson JL, Lundquist AL, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C virus‐associated mixed cryoglobulinemia with direct‐acting antiviral agents. Hepatology 2016;63:408‐417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arase Y, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Akuta N, Kobayashi M, Kawamura Y, et al. Sustained virological response reduces incidence of onset of type 2 diabetes in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2009;49:739‐744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hsu YC, Ho HJ, Huang YT, Wang HH, Wu MS, Lin JT, Wu CY. Association between antiviral treatment and extrahepatic outcomes in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Gut 2015;64:495‐503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hsu YC, Lin JT, Ho HJ, Kao YH, Huang YT, Hsiao NW, et al. Antiviral treatment for hepatitis C virus infection is associated with improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes in diabetic patients. Hepatology 2014;59:1293‐1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kraus MR, Schafer A, Teuber G, Porst H, Sprinzl K, Wollschlager S, et al. Improvement of neurocognitive function in responders to an antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2013;58:497‐504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The French METAVIR Cooperative Study Group . Intraobserver and interobserver variations in liver biopsy interpretation in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The French METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology 1994;20:15‐20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology 2006;43:1317‐1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.) . 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep 1992;41:1‐19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berenguer J, Zamora FX, Aldamiz‐Echevarria T, Von Wichmann MA, Crespo M, Lopez‐Aldeguer J, et al. Comparison of the prognostic value of liver biopsy and FIB‐4 index in patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:950‐958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fux CA, Simcock M, Wolbers M, Bucher HC, Hirschel B, Opravil M, et al. Tenofovir use is associated with a reduction in calculated glomerular filtration rates in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Antivir Ther 2007;12:1165‐1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bavinger C, Bendavid E, Niehaus K, Olshen RA, Olkin I, Sundaram V, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease from antiretroviral therapy for HIV: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e59551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berenguer J, Rodriguez E, Miralles P, Von Wichmann MA, Lopez‐Aldeguer J, Mallolas J, et al. Sustained virological response to interferon plus ribavirin reduces non‐liver‐related mortality in patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:728‐736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kawaguchi Y, Mizuta T. Interaction between hepatitis C virus and metabolic factors. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:2888‐2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Henry L, Younossi Z. Hepatitis. Chronic HCV infection, diabetes and liver‐related outcomes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;11:520‐521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Elkrief L, Chouinard P, Bendersky N, Hajage D, Larroque B, Babany G, et al. Diabetes mellitus is an independent prognostic factor for major liver‐related outcomes in patients with cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2014;60:823‐831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang YW, Yang SS, Fu SC, Wang TC, Hsu CK, Chen DS, et al. Increased risk of cirrhosis and its decompensation in chronic hepatitis C patients with new‐onset diabetes: a nationwide cohort study. Hepatology 2014;60:807‐814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dyson J, Jaques B, Chattopadyhay D, Lochan R, Graham J, Das D, et al. Hepatocellular cancer: the impact of obesity, type 2 diabetes and a multidisciplinary team. J Hepatol 2014;60:110‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Flemming JA, Yang JD, Vittinghoff E, Kim WR, Terrault NA. Risk prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: the ADRESS‐HCC risk model. Cancer 2014;120:3485‐3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lo Re V 3rd, Kallan MJ, Tate JP, Localio AR, Lim JK, Goetz MB, et al. Hepatic decompensation in antiretroviral‐treated patients co‐infected with HIV and hepatitis C virus compared with hepatitis C virus‐monoinfected patients: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:369‐379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Negro F. Hepatitis C in 2013: HCV causes systemic disorders that can be cured. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;11:77‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen YC, Lin HY, Li CY, Lee MS, Su YC. A nationwide cohort study suggests that hepatitis C virus infection is associated with increased risk of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2014;85:1200‐1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Molnar MZ, Alhourani HM, Wall BM, Lu JL, Streja E, Kalantar‐Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP. Association of hepatitis C viral infection with incidence and progression of chronic kidney disease in a large cohort of US veterans. Hepatology 2015;61:1495‐1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Margolick JB, Jacobson LP, Schwartz GJ, Abraham AG, Darilay AT, Kingsley LA, et al. Factors affecting glomerular filtration rate, as measured by iohexol disappearance, in men with or at risk for HIV infection. PLoS One 2014;9:e86311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Abraham AG, Althoff KN, Jing Y, Estrella MM, Kitahata MM, Wester CW, et al. End‐stage renal disease among HIV‐infected adults in North America. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:941‐949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Azmi AN, Tan SS, Mohamed R. Hepatitis C and kidney disease: an overview and approach to management. World J Hepatol 2015;7:78‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1296‐1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Park LS, Tate JP, Sigel K, Rimland D, Crothers K, Gibert C, et al. Time trends in cancer incidence in persons living with HIV/AIDS in the antiretroviral therapy era: 1997‐2012. AIDS 2016;30:1795‐1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Silverberg MJ, Chao C, Leyden WA, Xu L, Tang B, Horberg MA, et al. HIV infection and the risk of cancers with and without a known infectious cause. AIDS 2009;23:2337‐2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, Morlat P, Pradier C, Reiss P, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet 2014;384:241‐248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hsu CS, Kao JH, Chao YC, Lin HH, Fan YC, Huang CJ, Tsai PS. Interferon‐based therapy reduces risk of stroke in chronic hepatitis C patients: a population‐based cohort study in Taiwan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:415‐423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Arase Y, Kobayashi M, Kawamura Y, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Akuta N, et al. Impact of virus clearance for the development of hemorrhagic stroke in chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol 2014;86:169‐175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, Skanderson M, Lowy E, Kraemer KL, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:614‐622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Satapathy SK, Kim YJ, Kataria A, Shifteh A, Bhansali R, Cerulli MA, Bernstein D. Higher prevalence and more severe coronary artery disease in hepatitis C virus‐infected patients: a case control study. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2013;3:186‐191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pothineni NV, Delongchamp R, Vallurupalli S, Ding Z, Dai Y, Hagedorn CH, Mehta JL. Impact of hepatitis C seropositivity on the risk of coronary heart disease events. Am J Cardiol 2014;114:1841‐1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lin MS, Guo SE, Chen MY, Huang TJ, Huang JC, Hu JH, Lin YS. The impact of hepatitis C infection on ischemic heart disease via ischemic electrocardiogram. Am J Med Sci 2014;347:478‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Roed T, Kristoffersen US, Knudsen A, Wiinberg N, Lebech AM, Almdal T, et al. Increased prevalence of coronary artery disease risk markers in patients with chronic hepatitis C—a cross‐sectional study. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2014;10:55‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Adinolfi LE, Restivo L, Guerrera B, Sellitto A, Ciervo A, Iuliano N, et al. Chronic HCV infection is a risk factor of ischemic stroke. Atherosclerosis 2013;231:22‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Durand M, Sheehy O, Baril JG, LeLorier J, Tremblay CL. Risk of spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage in HIV‐infected individuals: a population‐based cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013;22:e34‐e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hsu YH, Muo CH, Liu CY, Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Sung FC, Kao CH. Hepatitis C virus infection increases the risk of developing peripheral arterial disease: a 9‐year population‐based cohort study. J Hepatol 2015;62:519‐525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gillis J, Smieja M, Cescon A, Rourke SB, Burchell AN, Cooper C, JM, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease associated with HCV and HBV coinfection among antiretroviral‐treated HIV‐infected individuals. Antivir Ther 2014;19:309‐317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Womack JA, Chang CC, So‐Armah KA, Alcorn C, Baker JV, Brown ST, et al. HIV infection and cardiovascular disease in women. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Momiyama Y, Ohmori R, Kato R, Taniguchi H, Nakamura H, Ohsuzu F. Lack of any association between persistent hepatitis B or C virus infection and coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2005;181:211‐213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Arcari CM, Nelson KE, Netski DM, Nieto FJ, Gaydos CA. No association between hepatitis C virus seropositivity and acute myocardial infarction. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:e53‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pothineni NV, Rochlani Y, Vallurupalli S, Kovelamudi S, Ahmed Z, Hakeem A, Mehta JL. Comparison of angiographic burden of coronary artery disease in patients with versus without hepatitis C infection. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:1041‐1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Petta S, Maida M, Macaluso FS, Barbara M, Licata A, Craxi A, Camma C. Hepatitis C virus infection is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of observational studies. Gastroenterology 2016;150:145‐155.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. He H, Kang R, Zhao Z. Hepatitis C virus infection and risk of stroke: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e81305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wong RJ, Kanwal F, Younossi ZM, Ahmed A. Hepatitis C virus infection and coronary artery disease risk: a systematic review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci 2014;59:1586‐1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. de Castro IF, Micheloud D, Berenguer J, Guzman‐Fulgencio M, Catalan P, Miralles P, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection is associated with endothelial dysfunction in HIV/hepatitis C virus coinfected patients. AIDS 2010;24:2059‐2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Adinolfi LE, Zampino R, Restivo L, Lonardo A, Guerrera B, Marrone A, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection and atherosclerosis: clinical impact and mechanisms. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:3410‐3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ishizaka N, Ishizaka Y, Yamkado M. Atherosclerosis as a possible extrahepatic manifestation of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Med Insights Cardiol 2014;8:1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Corey KE, Kane E, Munroe C, Barlow LL, Zheng H, Chung RT. Hepatitis C virus infection and its clearance alter circulating lipids: implications for long‐term follow‐up. Hepatology 2009;50:1030‐1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wheeler AL, Scherzer R, Lee D, Delaney JA, Bacchetti P, Shlipak MG, et al. HIV/hepatitis C virus coinfection ameliorates the atherogenic lipoprotein abnormalities of HIV infection. AIDS 2014;28:49‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Guzman‐Fulgencio M, Berenguer J, Fernandez de Castro I, Micheloud D, Lopez JC, Cosin J, et al. Sustained virological response to interferon‐α plus ribavirin decreases inflammation and endothelial dysfunction markers in HIV/HCV co‐infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66:645‐649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mostafa A, Mohamed MK, Saeed M, Hasan A, Fontanet A, Godsland I, et al. Hepatitis C infection and clearance: impact on atherosclerosis and cardiometabolic risk factors. Gut 2010;59:1135‐1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Christou L, Pappas G, Falagas ME. Bacterial infection‐related morbidity and mortality in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1510‐1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Collin A, Le Marec F, Vandenhende MA, Lazaro E, Duffau P, Cazanave C, et al. Incidence and risk factors for severe bacterial infections in people living with HIV. ANRS CO3 Aquitaine Cohort, 2000–2012. PLoS One 2016;11:e0152970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lai JC, Shoback DM, Zipperstein J, Lizaola B, Tseng S, Terrault NA. Bone mineral density, bone turnover, and systemic inflammation in non‐cirrhotics with chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:1813‐1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bedimo R, Cutrell J, Zhang S, Drechsler H, Gao A, Brown G, et al. Mechanisms of bone disease in HIV and hepatitis C virus: impact of bone turnover, tenofovir exposure, sex steroids and severity of liver disease. AIDS 2016;30:601‐608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Maalouf NM, Zhang S, Drechsler H, Brown GR, Tebas P, Bedimo R. Hepatitis C co‐infection and severity of liver disease as risk factors for osteoporotic fractures among HIV‐infected patients. J Bone Miner Res 2013;28:2577‐2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29071/suppinfo.

Supporting Information