Abstract

Background: Older Latinos with serious medical conditions such as cancer and other chronic diseases lack information about advance care planning (ACP). ACP Intervention (ACP-I Plan) was designed for informational and communication needs of older Latinos to improve communication and advance directives (ADs).

Objective: To determine the feasibility of implementing ACP-I Plan among seriously ill, older Latinos (≥50 years) in Southern New Mexico with one or more chronic diseases (e.g., cancer, heart disease, renal/liver failure, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and HIV/AIDS).

Design: We conducted a prospective, pretest/post-test, two-group, randomized, community-based pilot trial by using mixed data collection methods.

Setting/Subjects: Older Latino/Hispanic participants were recruited from community-based settings in Southern New Mexico.

Methods: All participants received ACP education, whereas the intervention group added: (1) emotional support addressing psychological distress; and (2) systems navigation for resource access, all of which included interactive ACP treatment decisional support and involved motivational interview (MI) methods. Purposive sampling was guided by a sociocultural framework to recruit Latino participants from community-based settings in Southern New Mexico. Feasibility of sample recruitment, implementation, and retention was assessed by examining the following: recruitment strategies, trial enrollment, retention rates, duration of MI counseling, type of visit (home vs. telephone), and satisfaction with the program.

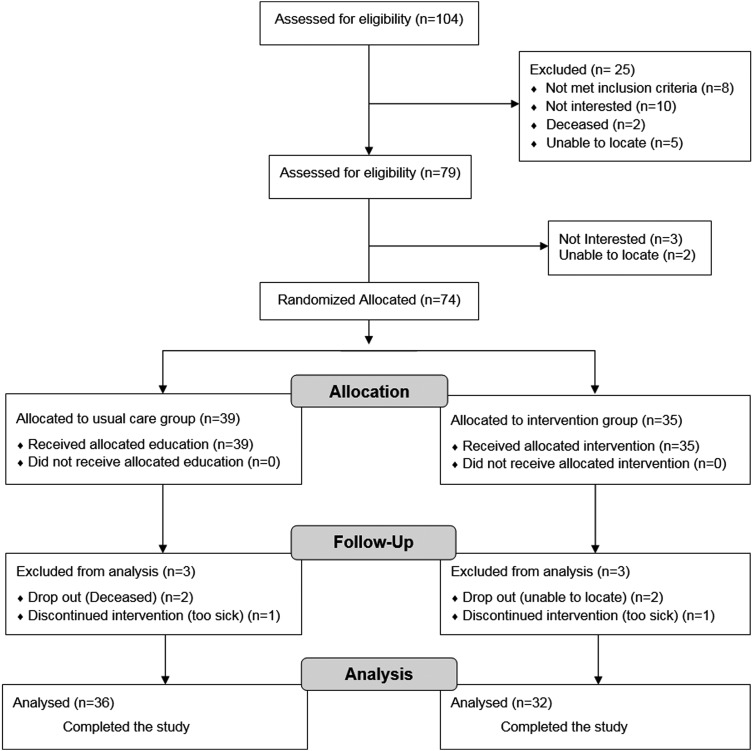

Results: We contacted 104 patients, enrolled 74 randomized to usual care 39 (UC) and treatment 35 (TX) groups. Six dropped out before the post-test survey, three from TX before the post-test survey because of sickness (n = 1) or could not be located (n = 2), and the same happened for UC. Completion rates were 91.4% UC and 92.3% TX groups. All participants were Latino/Hispanic, born in the United States (48%) or Mexico (51.4%) on average in the United States for 25 years; majority were female, 76.5%; 48.6% preferred Spanish; and 31.4% had less than sixth-grade education. Qualitative data indicate satisfaction with the ACP-I Plan intervention.

Conclusions: Based on enrollment and intervention completion rates, time to completion tests, and feedback from qualitative post-study, follow-up interviews, the ACP-I Plan was demonstrated to be feasible and perceived as extremely helpful.

Keywords: : advance care planning, advance directives, healthcare provider communication, Latino/Hispanic, qualitative research, social work issues

Introduction

Informed decision making is essential to advance care planning (ACP). Policies in the Patient Self-Determination Act1 indicate that ACP education, especially regarding advance directives (ADs), should be standard practice for healthcare providers. However, problems limiting end-of-life (EOL) care discussions hinder delivery of ACP information and completion of ADs in the United States.2 Although older adults with chronic diseases are more likely to have an AD than those without chronic disease,3 many individuals have not engaged in meaningful ACP discussions. Recommendations from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) suggest healthcare providers should routinely provide ACP education in their daily practice.4–6 Generally, there are high levels of information needed for individuals with serious illness, and especially for those facing the EOL7; however, ACP does not readily occur in medical settings.8 Interventions are needed to improve communication and delivery of ACP information, especially among individuals with chronic health conditions.9

Underserved patients with low socioeconomic status and limited English proficiency lack information about ACP and experience significant disparities (e.g., education, economic, social, linguistic, and cultural), limiting optimal decision making and EOL care communication.10–12 For example, individuals who do not speak English may also lack access to translation services, which hinder interactions with healthcare providers,13,14 making it difficult to communicate about ACP.11 Careful consideration about ACP education is especially important for racially and ethnically diverse patients (i.e., African Americans and Latinos).8 Along with a growing prevalence of multiple chronic conditions, U.S. Hispanics experience gaps in communication15 and significant barriers to management of their conditions.16 Older Latinos, living with serious illnesses, are especially vulnerable to misinformation because of disparities, limiting information provision and contributing to differential treatment, which plays an important role in medical decision making.17

Cultural beliefs and values also influence communication. Sociocultural factors influence ACP education and healthcare decision making stemming from patients' cultural beliefs and experiences for receiving such information.10,18 Latinos may not ask their healthcare providers direct questions or follow treatment plans, creating confusion between patients, family members, and providers.19 Lack of knowledge and ACP information create problems for EOL decision making.11 Factors such as low health literacy10,12,20 contribute to communication barriers and disadvantages for Latinos,21 which impact poor health outcomes.17,22,23 Although Latinos may prefer less-aggressive EOL treatment, they often have not documented or communicated their preferences to anyone.24 Although Latinos tend to accept more aggressive medical treatment compared with non-Hispanic whites,25,26 they often die in the hospital instead of at home without hospice care.27,28 Out of respect for healthcare providers, Latinos are known to follow physicians' treatment recommendations, often without asking questions because they may perceive that physicians have more education and knowledge in medicine, placing them in positions of authority.29 This indicates that when Latinos do not speak up about their preferences they could be accepting unwanted treatment without understanding or being aware of the implications of these actions. Cultural beliefs and values also influence preferences, suggesting that faith and family drive patient preferences.19 For example, Latinos can prefer to die at home,27 indicating that they prioritize the needs of the family over his or her own18 and have a desire to be close to extended-family networks; however, we have limited understanding about preferences for ACP communication or EOL care preferences for home, hospital, or other places of death. In addition, we lack understanding about family involvement in this process.

ACP education and decision-making discussions should happen early and often to inform everyone involved before the need for decision making. An early approach includes culturally adapted information10 and individualized care30 to improve EOL decision making to identify personal preferences. Initiation of early EOL conversations can lower distress among seriously ill individuals, improving quality of life.31,32 As suggested by the IOM Health Literacy and Palliative Care Workshop,20 community settings present a place where ACP education can openly occur, meeting the community needs, thereby reducing disparities.33 Instead of relying on healthcare providers to begin ACP conversations, education can happen, for example, in church settings and senior centers. Some individuals are open and prefer to receive ACP education in community-based settings34–36; however, very little research has been conducted with older, chronically ill Latinos, which is especially sparse among those living in rural settings. There is a growing need to educate older Latinos.

There are relatively few population-based research studies that pilot test the feasibility of conducting interventions with participants of similar sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, race, socioeconomic status, and education)37 and none that focus on a Hispanic population from a particular region with these characteristics and need for ACP information. Very few interventions are designed and tested to address ACP with this specific population, and none, to the best of our knowledge, have been conducted within community-based settings with older Latinos. This study addresses a key problem in ACP education among seriously ill older Latinos living in Southern New Mexico that examines feasibility and satisfaction of an ACP Intervention (ACP-I Plan) that is designed to meet informational and communication needs for ACP.

Methods

Design and participants

We conducted a prospective, pretest/post-test, two-group, randomized, community-based pilot trial by using mixed data collection methods. This study is a smaller part of a larger research project. In this study, we evaluate the feasibility of implementation and satisfaction with the ACP-I Plan. This feasibility study stems from pilot research wherein older Latinos were randomly assigned by flipping a coin to the ACP-I Plan treatment intervention group (TX) or usual care (UC).

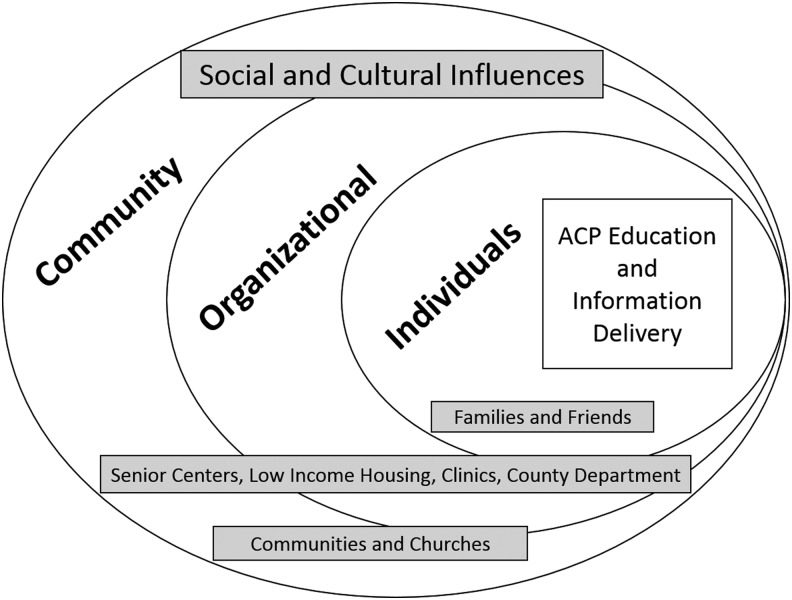

Sampling methods considered a sociocultural framework (Fig. 1) to purposively recruit Latino participants from community-based settings in Southern New Mexico and to maximize outreach efforts to the community. Using this framework, recruitment criteria included individuals, organizations, and communities to reach Hispanics/Latinos, age >50, living in Southern New Mexico, and having one or more chronic diseases (e.g., cancer, heart disease, renal/liver failure, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and HIV/AIDS). Recruitment data identified language preference, English/Spanish, or both.

FIG. 1.

Sociocultural context for recruitment strategies. ACP, advance care planning.

Screening assessed for conditions that could influence understanding of the intervention, excluding individuals if they answered yes to: “Has a doctor ever told you that you have: schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or manic/depressive disorder?” Exclusion criteria included the possibility of limited cognitive functioning that could impact decision making and research participation that asked, “Has a doctor ever told you that you have Alzheimer's disease?” Recruitment targeted populated urban and semirural areas in Southern New Mexico and surrounding colonies that are areas largely unregulated near the United States–Mexico border with minimal resources, high poverty, substandard housing, limited water sources, and inadequate roads.38

Procedures

The New Mexico State University Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the protocol and materials for this project. Patients provided written consent and received incentives for their participation: $5 for a screening interview to determine eligibility, $20 for a baseline survey, and $20 for completing a post-test survey. Written materials were available in English and Spanish. Per protocol, eligible participants were expected to complete a pretest survey soon after they screened as eligible, agreed to participate, and consented to the study. After the pretest survey, participants in the intervention group were scheduled and expected to complete one motivational interview (MI) counseling session after the educational session and within 30 days. Participants in both groups were expected to complete a post-test survey on or soon after 30 days from the pretest survey.39

A masters of social work (MSW) trained social worker provided participants with ACP education and counseling. Two study MSWs were trained on the intervention model, with approximately five hours of in-depth training to learn and practice ACP educational delivery, counseling, supportive communication techniques, and manage barriers. The intervention also addressed cultural elements that were shown to reduce barriers to ACP acknowledging individuals attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge about ACP.40 Additional training was provided to MSWs, with weekly team supervision meetings over the course of eight months, led by principal investigator (PI) to guide delivery of the intervention and improve recruitment strategies. MSWs administered all pretest/post-test surveys and conducted in-depth interviews.

Usual care group

General AD education was provided to all participants and included verbal and written information about ACP and ADs. During recruitment, AD information was introduced to all participants through a brief educational session before entering the study. We discussed specific information about the importance of appointing someone as power of attorney for healthcare decision making. We also discussed the application and limitation of medical decision making when an AD is needed, when an individual becomes unable to communicate their wishes for medical treatment. Education discussed decision making about medical treatment preferences to document on AD forms for specifying EOL care preferences. During ACP educational sessions, individuals asked questions about the forms to clarify any confusion on the process of documenting an AD. They were also encouraged to return to their healthcare providers with any medical questions that could influence decision making and AD documentation.

Treatment intervention group

The ACP-I Plan treatment intervention added one counseling session to general education about ACP to improve communication and AD documentation, combining interactive ACP treatment decisional support, counseling/emotional support, and barrier navigation. The intervention includes MI counseling39,41 and client-centered supportive care42,43 to encourage early ACP communication with healthcare providers and family members, addresses psychological distress through supportive counseling, and connects individuals to resources through patient navigation if needed.10,19,40,44 MI counseling uses a manualized protocol that is designed to help individuals explore their individual attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge about ACP. The MI session included supportive counseling for dealing with illness and talking to doctors, families, and friends about ACP, and it also explored “what is most important to you?” while considering attitudes and beliefs for talking about and/or planning EOL care. The TX group received a one-time MI session for 30–40 minutes; however, the amount of time spent with participants was individualized and based on request for more or less time. Per protocol, to individualize care, an additional follow-up session was offered as needed. Three participants requested and received an additional brief follow-up counseling discussion, which lasted no more than 15 minutes.

Feasibility measures

Before implementation, proposed benchmarks for feasibility were defined for indicators described in this section (Table 3). Feasibility is indicated by sample recruitment and study implementation examining the following: recruitment strategies to indicate a broad range of various methods and descriptive data on the demographics to show information about the target population. Screening measures in recruitment were used to report age, race, type of chronic medical conditions, number of emergency room (ER) or urgent care visits, and number of hospitalizations in the past six months to indicate the severity of illness on recruitment. We tracked language preference (English/Spanish) and type of preferred visit (face to face vs. telephone). Feasibility was also measured by number of participants screened, number enrolled, retention rate, attrition rate, duration of MI counseling, and satisfaction with the program.42 We also tracked38,40 the time it took between screening to pretest survey and to post-test survey, as well as the examining of the duration and type of visit (phone or in-person).

Table 3.

Measures of Feasibility

| Proposed benchmark | Actual | |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment strategies | a | Various strategies |

| Sample demographics | a | Descriptive data |

| Participants screened | n = 100 | n = 104, 104% |

| Trial enrollment | n = 50 | n = 74, 148% |

| Retention rate | >80% | (68), 91.9% |

| Attrition rate | <20% | (6), 8.1% |

| Type of visit | Preference | |

| Face to face | a | 79.4% |

| Telephone | a | 20.6% |

| Time | ||

| Screen to pretest | As soon as possible | 9 days (median = 3, SD = 15.32) |

| Pretest to MI counseling | As soon as possible | 18 days (median = 14, SD = 13.90) |

| Pretest to post-test | <30 days | 14 days (median = 6, SD = 19.42) |

| MI counseling duration | One, 30- to 40-minute session | Mean = 33 minutes, SD = 10.11 minutes |

| Satisfaction | Level | Qualitative data |

Variation for proposed sampling and recruitment strategy.

MI, motivational interview.

Data analysis

Mixed qualitative and quantitative methods were used to examine the feasibility of recruitment and satisfaction with the program, including data from screening, pretest/post-test surveys, and qualitative interviews. Baseline data were used to examine the feasibility of recruitment and qualitative semistructured, open-ended interviews45 were used to examine satisfaction as acceptance with the intervention. Tests for significance and change scores from pretest to post-test were not done as this study focused on feasibility. Measures of feasibility were calculated. Satisfaction was assessed as a proxy for acceptance with and retention in the program. Qualitative interviews were conducted after participants completed the post-test survey. A semistructured interview guide included questions on: satisfaction with ACP education, ACP communication with family and healthcare providers, social and cultural factors that influence discussions, emotions such as fear or denial that influence ACP communication, and suggestions for improvement of ACP information (Table 1).

Table 1.

Questions for Exit Interview Guide

| Satisfaction | How satisfied were you with this education? |

| How can we improve this information for patients? | |

| ACP communication | What about talking with family members about medical decision making? |

| What about talking with healthcare providers? Asking questions? | |

| What kind of things make it more difficult to talk about ACP? | |

| What kind of things make it easier to talk? | |

| What about language? Spanish or English? | |

| How does education level influence ACP communication? | |

| Healthcare providers | What about your relationship with your doctor? |

| Some people say they are afraid to ask their doctor questions. | |

| What about fear of talking with your doctor about ACP? | |

| Have you ever experienced discrimination? | |

| Sociocultural factors | What about social and cultural issues of Latinos that influence ACP discussions? |

| What about family involvement? What about religious or spiritual issues? | |

| What about religious or spiritual issues? | |

| Emotions | What about fear and talking about ACP? |

| What about denial? |

ACP, advance care planning.

Data from all sources, including audio recordings, transcribed interviews, team meeting memos, notes, and case summaries, were used for descriptive analysis that were analyzed in Atlas.ti, an analytical software46 using a constant comparative method and thematic analysis.47,48 Analysis involved a team approach and iterative methods to identify salient themes regarding recruitment strategies in community-based settings and to explore satisfaction. First, to ensure trustworthiness of the findings,49 two team members (coauthors, K.J.G. and A.Q.) reviewed and coded the data independently, creating categories, subcategories, and themes inductively from the codes. Then, a third person (F.N.H.) reviewed the coding schema and refined the concepts. Team meetings and multiple discussions were used to resolve discrepancies and to reach a coding consensus. Once key findings were identified, a fourth team member, who did not participate in data collection, reviewed the coding strategy to summarize the identified concepts, themes, and subthemes that emerged.

Results

Feasibility outcomes

Recruitment strategies

Using the sociocultural framework, we maximized recruitment with outreach methods to reach a maximum number of participants for the study. Outreach was conducted by reaching individuals, families, and friends, and at the organizational and community levels. As a research team, two MSW trained social workers who were fluent in Spanish entered the community weekly for a six-month period, posting information about the study as well as talking with people who were interested in this study. The process of recruitment included posting and handing out flyers, sending e-mails to community members, holding meeting with stakeholders in governmental agencies, and providing AD educational sessions with older adults in senior community centers, social service agencies, low-income housing projects, food banks, grocery stores, local community churches, and assisted living facilities. In terms of the number of people approached before recruiting the target population, ∼225 flyers were given out during the recruitment period.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Demographic information about the sample indicates the likelihood of actually recruiting the target population, which is especially important for Latinos/Hispanic individuals who historically have neither participated in research37 nor received ACP education in English or Spanish. Table 2 summarizes the background characteristics of the participants. The mean age of participants was 65.79 (standard deviation [SD] = 8.71; range 50–87). The majority were women, 76.5%. All participants identified as Latino/Hispanic, born in the United States (48%) or born in Mexico (51.4%) on average living in the United States for 25 years, 52.9% preferred Spanish, and 31.4% had less than sixth-grade education. For illness severity, participants had at least one chronic condition (10.3%); however, most had 2 (51.5%) or 3 (32.4%) conditions, with urgent care needs (38.2%, ER, urgent care, or hospitalization).

Table 2.

Demographics

| Number, mean% or range | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total (n = 68) | UC (n = 36) | Intervention (n = 32) | |||

| Age | 65.79 (SD 8.71) | (50–87) | 66.61 (SD 5.373) | 64.88 (SD 11.39) | ||

| Female | 52 | 76.5% | 28 | 77.8% | 26 | 74.3% |

| Latino/Hispanic | 68 | 100% | ||||

| Birthplace | ||||||

| United States | 31 | 45.6% | 15 | 41.7% | 16 | 50% |

| Mexico | 37 | 54.4% | 21 | 58.3% | 16 | 50% |

| Born in Mexico, Length of years in the United States | 35.54 (SD 15.30) | (4–62) | 16 | 31.75 (SD 16.22) | 21 | 38.24 (SD 14.36) |

| Language preference | ||||||

| English | 21 | 30.9% | 11 | 30.6% | 10 | 31.3% |

| Spanish | 36 | 52.9% | 21 | 58.3% | 15 | 46.9% |

| Both English/Spanish | 11 | 16.2% | 4 | 11.1% | 7 | 21.9% |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 22 | 32.4% | 13 | 36.1% | 9 | 28.1% |

| Widowed | 15 | 22.1% | 7 | 19.4% | 8 | 25.0% |

| Divorced | 15 | 22.1% | 10 | 27.8% | 5 | 15.6% |

| Separated | 6 | 8.8% | 2 | 5.6% | 4 | 12.5% |

| Never married | 7 | 10.3% | 4 | 11.1% | 3 | 9.4% |

| Living with partner | 3 | 4.4% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 9.4% |

| Education | ||||||

| <6th grade | 19 | 27.9% | 9 | 25.0% | 10 | 31.3% |

| 7th–11th | 12 | 17.6% | 5 | 13.9% | 7 | 21.9% |

| High school | 20 | 29.4% | 11 | 30.6% | 9 | 28.1% |

| >High school | 17 | 25.0% | 11 | 30.6% | 6 | 18.8% |

| Chronic medical conditions | ||||||

| Hypertension | 52 | 76.5% | 30 | 83.3% | 22 | 68.8% |

| Diabetes | 47 | 69.1% | 27 | 75.0% | 20 | 62.5% |

| Cancer | 28 | 41.2% | 12 | 33.3% | 16 | 50.0% |

| Heart disease | 16 | 23.5% | 8 | 22.2% | 8 | 25.0% |

| Liver failure | 8 | 11.8% | 5 | 13.9% | 3 | 9.4% |

| Stroke | 7 | 10.3% | 5 | 13.9% | 2 | 6.3% |

| COPD | 5 | 7.4% | 4 | 11.1% | 1 | 3.1% |

| HIV/AIDS | 2 | 2.9% | 1 | 2.8% | 1 | 3.1% |

| Comorbid medical conditions | ||||||

| 1 | 7 | 10.3% | 3 | 8.3% | 4 | 12.5% |

| 2 | 35 | 51.5% | 18 | 50.0% | 17 | 53.1% |

| 3 | 22 | 32.4% | 12 | 33.3% | 10 | 31.3% |

| 4 | 4 | 5.9% | 3 | 8.3% | 1 | 3.1% |

| In past six months, ER or urgent care visit | 26 | 38.2% | 11 | 30.6% | 15 | 46.9% |

| In past six months, hospital stay | 26 | 38.2% | 12 | 33.3% | 14 | 43.8% |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ER, emergency room; SD, standard deviation; UC, usual care.

Participation

We contacted 104 patients (Fig. 2); 74 agreed to participate and were randomized 39 to UC versus 35 to TX. Three dropped out before the post-test survey because they were too sick (n = 1) or could not be located (n = 2), and 3 patients from UC dropped out before the post-test survey. The overall completion rate was 92%, with 91.4% for UC and 92.3% for TX groups.

FIG. 2.

Study enrollment.

Time

See Table 3 for actual measures of feasibility. On average, pretest surveys were completed nine days after eligibility screening (median = three days, SD = 15.32), MI counseling was conducted 18 days after screening (median = 14, SD = 13.90), and post-test surveys were completed 14 days after the pretest survey (median = six days, SD = 19.42). For the duration of MI counseling to encourage ACP communication and AD documentation, participants were expected to participate in a 30- to 40-minute session. On average, this one-time session took ∼30 minutes (mean = 33 minutes, SD = 10.11 minutes). For the MI session delivery format, 22% of the sessions were conducted over the telephone and 78% were conducted face to face.

Satisfaction

All participants reported having a positive experience with ACP-I Plan (Table 4). Many said that ACP information was useful and fulfilled a gap in knowledge or information that brought attention to ACP and ADs. For some, it was the first time they had learned about ACP. Others said that the program added information that helped them to think and/or to talk with family members and doctors about ACP. One participant said,

Table 4.

Satisfaction

| Satisfaction codes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Simply satisfied | I like it a lot. I think it's great. (#14 is a 71-year-old female, UC) |

| Fulfilled a need (knowledge gap), to learn about ACP | I'm satisfied because I've been able to learn something. (#8 is a 69-year-old female, UC) |

| What you taught me helped me a lot…Because you talked to me about a lot of things that I've never talked about. (#33 is a 69-year-old female, UC) | |

| Fulfilled a need (information gap), to receive ACP information | Yes, to learn about that because I didn't know about that, to know about the advance directives. I think it is good how you have it, a lot of information. (#61 is a 73-year-old female, TX) |

| Fulfilled a need to be prepared for ACP | I'm satisfied with it because already I've managed to rethink my illness, to have everything in order, papers for the doctors, my daughters and my friends that they know how I am. But, in between the advice you have given me…I understand what is being said. It's true, it's not a game, that they understand what they're asking, what they say, so that they're prepared for the day. One is anticipating, already talked to you and prepared. (#73 is a 60-year-old female, TX) |

| Fulfilled an expectation that ACP needs to be done, to take action. May be difficult to do. Perceptions that ACP actions are important | Well, I've learned a lot of things, you know, what you're supposed to do, get ready, and everything else. I wasn't aware of that. I mean, I knew that you had to do a will or something like that, but I had told my daughter and I thought that was enough, you know? But, it's better to be written down and that way there's no problems. It's better to be ready to not have problems. (#71 is a 80-year-old female, TX) |

| ACP is hard or difficult to do | You have shown me a lot and I am learning a lot. I didn't know about this, that there was help for people like this. It's important because I don't want to talk much about that…It's hard to talk about those topics. (#11 is a 78-year-old female, TX) |

| Understood importance of talking about ACP (talking) | I was satisfied with it….I think you do it pretty good…make them understand that it's best for them to have a living will. (#27 is a 62-year-old female, UC) |

| Understood importance of ACP (documentation) | I just need to sit down and just do it and maybe have my husband or a family member there, and sit down with me and just write it out, you know. (#7 is a 62-year-old female, UC) |

| It's taught me that it's a wise thing to do when it comes to documentation. (#69 is a 77-year-old female, UC) | |

| Helpful to me to talk to others | I'm very satisfied, you bringing up the topic itself about like the advanced directives and all that. I've been able to talk a little bit more about it to my family. But, hearing more about it, then it made me think about it more. (#21 is a 54-year-old female, TX) |

| Helpful to others, beneficial for them too | I'm satisfied for the simple reason that I'm participating in something that might be a program that will benefit many people. (#32 is a 65-year-old male, UC) |

| Helped me feel better | I'm at ease. I can sleep peacefully. I feel more peaceful now that you have talked with me. Yes, because now I'm prepared for everything. One is not closed off. (#73 is a 60-year-old male, TX) |

| Fulfilled a need to avoid conflict in the future | You provide a lot of good information that helps to make a good decision in the process. When I first found out about this, I think I realized how important it was to do it, because sometimes people don't realize that it's a good thing to do, like when you're healthy, not at the end when it's too late and you can't even speak for yourself. Mm-hm. It's helped me a lot because, well, this person went through a lot. Actually, sometimes even fighting with the doctors because the doctors did not want to honor her wishes. And that's what you have to do, you know? And sometimes it's very, very hard. I mean, you have to fight and fight and fight, you know? And, if you don't have the strength to do it, then they win and they do whatever they want to do, you know? So that's all it boils down to, to do it. (#12 is a 63-year-old female, UC) |

| Helped me to talk with doctor | I tell you that it was good, but…because at first I didn't understand, because I wondered, why are they asking me this and everything? Then, I talked with my doctor, what were they saying about this and that? And he explained it to me. And, I'm more satisfied. And so I told him…“Oh, okay.” But, I asked, “Why are they asking me these questions?” And, I told the doctor, “I didn't like these questions.” I didn't know why they were asking me these questions. “Did they want me to die now!?” And the doctor assured me, “no, no.” He told me what it was about and explained it to me too. “It's for you to know about what to do when you're going to die, or if you were alone and no one knows what you want, to tell your children who are not here now.” (#75 is a 54-year-old female, TX) |

| Helped me to talk with my family | It's helped me…the questions that you ask that I never thought of….[and] you know, that way they might open up. So, my daughter and I got together…just me and her, and then we talked to the other kids about it. (#13 is a 79-year-old male, TX) |

| Make sure follow wishes | I don't want something that's going to be done that I didn't want it to be done. That's what makes me think…I mean, I should do it because what if they keep me on a ventilator for two, three years, and that's not what I want. (#70 is a 59-year-old female, UC) |

| Getting closer to death | I don't want to talk much about that…because in life, death is getting closer. (#11 is a 78-year-old female, TX) |

| Addressed a need for ACP for Hispanic culture | I think it's very good. I thought it was a very good study. And I think that because Hispanic women have a tendency to use remedies or to depend on family members, maybe depend on children to the point of alienating them. So, I think that sometimes that something like this is very helpful. Very helpful…maybe in helping somebody else too. Maybe being able to share information with somebody else. Well, because I think that we need to see it. We need to have it in black and white because so many times we hear things and maybe we're not paying complete attention. And then, we think back, now well, what do I need to do about this? What did she say about this? So, being able to read it and have it in front of me, I think is very important. (#19 is a 66-year-old female, UC) |

TX, treatment; UC, usual care.

I'm real happy with it. You kind of asked me questions that I never even thought about…like, questions I didn't want to think about and showed me a lot about the will. Now, I can deal with it. So that's helped me a lot. (74 UC)

Participants were satisfied because the program fulfilled a need to be prepared for the future when entering the hospital or when their family members are called to make decisions. Although most participants talked about satisfaction, some (16%) indicated being simply satisfied without providing more information about their satisfaction. Among these individuals, they either spoke Spanish only with having less than a sixth-grade education or were English speaking with only a high school degree. Limited expressions of satisfaction appear to indicate gaps in health literacy and ability to articulate ideas about ACP.

Participants provided positive feedback and suggestions to improve the ACP-I Plan intervention (Table 4); comments suggest increasing the number of educational sessions in various community settings where older adults can talk about the process of ACP. Some participants emphasized that older adults need vital ACP information repeated multiple times so that they have concrete examples and suggestions about documenting an AD. Although the information was clear and straightforward, participants would like MSWs to encourage them to ask more questions, especially because they may have difficulty understanding the information. Another consideration for improvement included aspects of faith and religiosity in the discourse on ACP to allow people to express how they feel about the process and their faith. Some participants suggested engaging chaplains or their church pastors so that there could be an ACP discussion that incorporated aspects of their faith in communication. Talking about ACP can raise emotions such as anxiety or fear about dying. Since these discussions take time, participants suggested that providers allow for more time so that feelings can emerge to be expressed in the process.

Discussion

This study highlights findings of a randomized, community-based pilot trial ACP-I Plan and explores the feasibility of implementation and satisfaction with the program, providing suggestions for improvement. Findings indicate that the ACP-I Plan is feasible to implement in Southern New Mexico with older Latinos and that participants were satisfied with the program. Although previous research finds low participation rates among Hispanics/Latinos in research, this study successfully enrolled and completed the trial with 68 participants enrolled from Southern New Mexico.

The ACP-I Plan intervention development was guided by a conceptual model of MI that intended to improve ACP communication and AD documentation for Hispanic/Latinos with chronic medical conditions. Recruitment methods implemented in Southern New Mexico to enroll the study population resulted in 74 participants who were randomly assigned to UC and intervention groups; there was an overall participation rate of 93.7%. Based on enrollment and intervention completion rates, time to completion, and feedback from a qualitative post-study, follow-up interviews, the ACP-I Plan was demonstrated to be feasible and perceived as extremely helpful. This is important because no study to date has been conducted with this population and implemented in a community-based setting.

When older Latinos experience chronic illness, they may become more vulnerable when entering the medical system. Without previous decision-making discussions and lack of AD documentation, they may rely on family members50; however, surrogate preferences can differ from patients' goals, leading to family conflict regarding treatment options.51,52 This study indicates that older Latinos are receptive to ACP communication and appreciate an opportunity to begin early discussions to prevent family conflict and confusion for everyone.

Disparities and added vulnerabilities for Latinos indicate the importance of early ACP education. Although vulnerability is a human condition that influences healthcare delivery, certain populations experience disparate circumstances that negatively impact information delivery and lead to misinformation and gaps in care.53 Some individuals encounter hardships and are more vulnerable than others, living with poverty, homelessness, or disability influencing differential treatment in EOL care.54 Our study addresses this gap by targeting the specific population with a culturally adapted approach to ACP information, providing individualized attention to their educational and linguistic needs.

Limitations

Several considerations and limitations should be considered. The ACP-I Plan was designed as a multifaceted intervention to provide ACP education and counseling to chronically ill, older Latinos to explore the possibility of recruitment and implementation of ACP. Purposive, convenient sampling was used to expand recruitment strategies that could influence a selection bias toward recruiting participants for this study. Therefore, data should not be generalized to all older Latinos. Future research will consider methods to control for selection bias. In addition, since healthcare providers should routinely integrate ACP information into daily practices, especially with seriously ill patients, it is unclear how much ACP information was received or understood before beginning the study. In future research, it is essential to assess knowledge of ACP on screening.

Conclusion

Based on enrollment and intervention completion rates, time to completion, and feedback from qualitative post-study, follow-up interviews, the ACP-I Plan was demonstrated to be feasible and perceived as extremely helpful in understanding and navigating ACP.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants who were the reason for developing and pilot testing the Advance Care Planning Intervention (ACP-I Plan) intervention, with a special appreciation for the Southern New Mexico community members who supported this research program. The ACP-I Plan pilot study was supported by the Mountain West, Clinical Translation Research Infrastructure Network (5U54GM104944 pilot grant).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Office GUSGA. Advance directives: Information on federal oversight, provider implementation, and prevalence, 2015. www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-416 (Last accessed June23, 2016)

- 2.Kale MS, Ornstein KA, Smith CB, Kelley AS: End‐of‐life discussions with older adults. J Am Geriatrics Society 2016;64:1962–1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin F-C, Laux JP: Completion of advance directives among US consumers. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:65–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosgrove D, Fisher M, Gabow P, et al. : A CEO Checklist for High-Value Health Care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emanuel L, Scandrett KG: Decisions at the end of life: Have we come of age? BMC Medicine 2010;8:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues, Institute of Medicine Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. : A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: Patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34:81–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahluwalia SC, Levin JR, Lorenz KA, Gordon HS: Missed opportunities for advance care planning communication during outpatient clinic visits. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:445–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walczak A, Butow PN, Bu S, Clayton JM: A systematic review of evidence for end-of-life communication interventions: Who do they target, how are they structured and do they work? Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:3–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nedjat-Haiem FR, Carrion IV, Ell K, Palinkas L: Navigating the advanced cancer experience of underserved Latinas. Supportive Care Cancer 2012;20:3095–3104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrion IV, Nedjat-Haiem FR, Martinez-Tyson D, Castaneda H: Advance care planning among Colombian, Mexican, and Puerto Rican women with a cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 2012;21:1233–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrion IV: Communicating terminal diagnoses to Hispanic patients. Palliat Support Care 2010;8:117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derose KP, Escarce JJ, Lurie N: Immigrants and health care: Sources of vulnerability. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:1258–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derose KP, Baker DW: Limited English proficiency and Latinos' use of physician services. Med Care Res Rev 2000;57:76–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nedjat-Haiem FR, Carrion IV, Gonzalez K, et al. : Exploring health care providers' views about initiating end-of-life care communication. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2016;34:308–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.John Snow, Inc. (JSI): An Inside Look at Chronic Disease and Health Care Among Hispanics in the United States, Washington DC: National Council of La Raza, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elder JP, Ayala GX, Parra-Medina D, Talavera GA: Health communication in the Latino community: Issues and approaches. Annu Rev Public Health 2009;30:227–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nedjat-Haiem FR, Lorenz KA, Ell K, et al. : Experiences with advanced cancer among Latinas in a public health care system. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;43:1013–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alper J: Health Literacy and Palliative Care: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medina CK, Negroni LK: LATIN@ ELDERS: Securing healthy aging inspite of health and mental health disparities. In: The Collective Spirit of Aging Across Cultures. Springer Netherlands, 2014, pp. 65–85 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. : Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA-Cancer J Clin 2004;54:78–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, et al. : Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences. J Palliat Med 2008;11:754–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelley AS, Wenger NS, Sarkisian CA: Opiniones: End‐of‐life care preferences and planning of older latinos. J Am Geriatrics Society 2010;58:1109–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwak J, Haley WE: Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist 2005;45:634–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blackhall LJ, Frank G, Murphy ST, et al. : Ethnicity and attitudes towards life sustaining technology. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:1779–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colon M: Hospice and Latinos: A review of the literature. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2005;1:27–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, et al. : Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: Why do minorities cost more than whites? Arch Intern Med 2009;169:493–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nedjat-Haiem FR, Carrion IV: Assessing challenges in end-of-life conversations with patients utilizing a public safety-net health care system. J Hospice Palliat Care 2015;32:528–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: Toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:755–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Block S: Involving Physicians in Upstream Conversations: The Serious Illness Communication Checklist. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2012;2:187 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis H, Hackner D: Early and effective goals discussions a critical review of the literature. ICU Director 2010;1:155–162 [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Institutes of Health U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Strategic research plan to reduce and ultimately eliminate health disparities. www.nimhd.nih.gov/documents/volumei_031003edrev.pdf (Last accessed May3, 2016)

- 34.Bullock K, McGraw SA, Blank K, Bradley EH: What matters to older African Americans facing end-of-life decisions? A focus group study. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2005;1:3–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waters CM: End-of-life care directives among African Americans: Lessons learned-A need for community-centered discussion and education. J Community Health Nurs 2000;17:25–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ko E, Berkman CS: Advance directives among Korean American older adults: Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. J Gerontol Soc Work 2012;55:484–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK: Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health 2006;27:1–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Núñez GG: The political ecology of colonias on the USA–Mexico border: Ethnography for hidden and hard-to-reach communities. In: The International Handbook of Political Ecology. 2015, p. 460 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skulason B, Hauksdottir A, Ahcic K, Helgason AR: Death talk: Gender differences in talking about one's own impending death. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ell K, Vourlekis B, Xie B, et al. : Cancer treatment adherence among low‐income women with breast or gynecologic cancer. Cancer 2009;115:4606–4615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller W, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. New York: Guilford Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rogers C: On Becoming a Person: A Therapist's View of Psychotherapy. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers CR: Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications, and Theory. Boston: Riverside Press, 1951 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ell K, Vourlekis B, Lee P-J, Xie B: Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: A randomized clinical trial. Prev Med 2007;44:26–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Britten N: Qualitative research: Qualitative interviews in medical research. BMJ 1995;311:251–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muhr T: User's Manual for ATLAS.ti 5.0, 2nd ed. Berlin, Germany: Scientific Software Development, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strauss A, Corbin J: Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strauss A: Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Padgett DK: Qualitative Methods in Social Work Research, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM: Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1211–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hawkins NA, Ditto PH, Danks JH, Smucker WD: Micromanaging death: Process preferences, values, and goals in end-of-life medical decision making. Gerontologist 2005;45:107–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D: The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:493–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nedjat-Haiem FR, Carrion IV, Cribbs K, Lorenz K: Advocacy at the end of life: Meeting the needs of vulnerable Latino patients. Soc Work Health Care 2013;52:558–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stienstra D, Chochinov HM: Palliative care for vulnerable populations. Palliat Support Care 2012;10:37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]