Abstract

A new drug delivery strategy was investigated for the development of potent anti-parasitic compounds against Trypanosoma brucei, the causative agent of African sleeping sickness. Thus, potent in vitro hexokinase inhibitors were rendered cytotoxic by appending a tripeptide peroxosomal targeting sequence that facilitated delivery of the molecular cargo to the appropriate organelle in the parasite.

Keywords: African Sleeping Sickness, benzamidobenzoic acid, trypanosomes, Peroxosomal Targeting Sequence

Graphical abstract

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), commonly called African sleeping sickness, is transmitted by the tsetse fly and is caused by trypanosomes of the species Trypanosoma brucei.1 The disease is endemic to sub-Saharan Africa, where millions of people are at risk for infection.2,3 Although treatments have existed for a number of years, these therapeutics are marked by serious adverse side-effects, such as acute toxicity, neural disorders, and in some cases, death.2,4

Bloodstream form (BSF) trypanosomes generate ATP for energy via glycolysis, in which the first step involves the formation of glucose-6-phosphate via the transfer of a phosphoryl group from ATP to the 6′ hydroxyl group on glucose.1,3,4,5 This process is catalyzed by two hexokinases, TbHK1 and TbHK2, with the former having been genetically and chemically validated for therapeutic design.2–4 Through a high-throughput screening (HTS) campaign and follow-on small molecule probe development, benzamidobenzoic acid (BABA) derivatives were identified as potent inhibitors of recombinant TbHK1 (i.e. rTbHK1) in vitro.2 In this initial screen, BABA 1 (Figure 1) emerged as a promising hit compound,2 and represented a convenient starting scaffold for the exploration of structure-activity relationships (SAR) through a medicinal chemistry campaign.6 An initial round of SAR study revealed ML205 (i.e. 2) to be a potent inhibitor of rTbHK1 (IC50 = 0.98 ± 0.07 μM). Nonetheless, compound 2 was not an effective trypanocide against whole-cell BSF parasites. Finally, compound 2 had no impact on a mammalian hexokinase, and exhibited no appreciable toxicity toward human cell lines, confirming that this drug scaffold is amenable for the selective inihibition of trypanosomal hexokinases for therapuetic gain.2,6

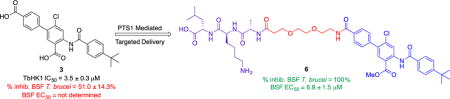

Figure 1.

BABA TbHK1 inhibitors and PTS1-BABA conjugates.

As an alternative to a conventional medicinal chemistry approach toward lead optimization, we describe herein a relatively underexplored and synthetically simple strategy toward achieving potency against live trypanosomes. Namely, we have successfully improved the trypanocidal activity of a derivative of 2 (i.e. compound 3) by conjugating the drug to a tripeptide peroxisomal targeting sequence (i.e. PTS1)7–10 that ensures delivery of the agent to the glycosome, the organelle that houses the glycolysis machinery in trypanosomes. Similar to ML205, compound 3 is a reasonably potent rTbHK1 inhibitor (i.e. IC50 = 3.5 ± 0.3 μM) that exhibits relatively poor performance against whole-cell BSF T. brucei (i.e. ~51% growth inhibition at 10 μM). Unlike ML205, compound 3 harbors a second carboxylic acid moiety (highlighted in green) that represented a convenient handle for the installation of a peptide linker and PTS1.

In trypanosomes, molecular cargo bound for glycosomes typically bears a peroxisome targeting sequence (PTS).10 The PTS type 1 sequence has been employed previously to deliver both proteinaceous cargo7–9 and a pH sensor to the glycosome in trypanosomes,10 but this appealing strategy has never been exploited for the delivery of a small-molecule drug with the aim of developing potent trypanocides. Because TbHK1 is a glycosome-resident protein, we surmised that a potent TbHK1 inhibitor exhibiting poor whole-cell activity might be rescued by appending a PTS1 sequence through relatively straight-forward synthetic operations. Thus, we designed four derivatives of 3 that incorporate a PTS1 tripeptide via an intervening diglycine or diethylene glycol linker (Figure 1, 4–7). The synthesis of PTS1-BABA conjugates 4–7 began with the iodination of 2-amino-4-chloro-methyl benzoate 8 with molecular iodine in the presence of silver (I) sulfate to afford iodinated aniline derivative 9 in quantitative yield.11 Iodo-aniline 9 was then subjected to Suzuki coupling conditions with 4-tert-butyloxycarbonyl phenylboronic acid to afford biaryl aniline derivative 10 in 96% yield.12 Next, tert-butyl benzoic acid was converted to its corresponding acid chloride by action of thionyl chloride and triethylamine, and biaryl aniline derivative 10 was then added to afford the tert-butyl ester 11 in 54% yield. The tert-butyl ester functionality in 11 was then cleaved by trifluoroacetic acid to afford the mono-carboxylic acid 12, poised for coupling with the linker and PTS1. Mono-acid 12 was saponified with aq. LiOH in THF to provide the previously evaluated13 BABA diacid 3.

The PTS1-BABA conjugates 4–7 were prepared by coupling the appropriate linker region and the LKA PTS1 sequence onto mono-acid 12 by routine Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) using the ultra-reactive uronium reagent, HCTU14, along with conventional deprotection and resin cleavage protocols15 (See ESI for details). The SPPS protocol returned the PTS1-BABA methyl esters 4 and 6, which could be subsequently converted to the PTS1-BABA carboxylic acids 5 and 7 by saponification.

Next, we evaluated PTS1-BABA conjugates 4–7 as TbHK1 inhibitors and as trypanocides against BSF T. brucei cultures. Our biological screening returned four parameters: % TbHK1 inhibition at 10 μM drug concentration, IC50 values for TbHK1 inhibition (i.e. drug concentration capable of effecting 50% inhibition of TbHK1 activity), % growth inhibition of BSF T. brucei at 10 μM drug concentration, and BSF EC50 values (i.e. drug concentration capable of killing 50% of trypanosomes in culture). BABA derivatives 2, 3, 11, and 12 along with the peptide-drug conjugates 4–7 were initially evaluated against both rTbHK1 and BSF T. brucei at 10 μM (See ESI for details). Based on the results of these initial screens, the compounds were evaluated in a dose-response format to calculate the IC50 and EC50 values for rTbHK1 and BSF T. brucei inhibition, respectively. The results of these assays are collected in Table 1.

Table 1.

Biological data for BABA derivatives and PTS1-BABA conjugates.[a]

| Entry | Compound | TbHK1% inhibition (10 μM) | TbHK1 IC50 (μM) | %BSF Growth Inhibition (10 μM) | BSF EC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | – | 0.98 ± 0.067 | 6.9 ± 3.0 | >10 |

| 2 | 3 | 93.6 ± 2.8 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 51.0 ± 14.3 | >10 |

| 3 | 11 | 0 | >10 | 9.6 ± 9.7 | >10 |

| 4 | 12 | 87.1 ± 3.5 | >10 | 24.5 ± 6.8 | >10 |

| 5 | 4 | 0 | >10 | 0 | >10 |

| 6 | 5 | 26.3 ± 3.8 | >10 | 0 | >10 |

| 7 | 6 | 10.5 ± 3.6 | >10 | 100 | 6.8 ± 1.5 |

| 8 | 7 | 67.5 ± 4.6 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 38.9 ± 11.1 | >10 |

Trypanosome cultures were assayed in triplicate in a total volume of 40 μL, and the DMSO vehicle was used as a negative control. Percent inhibition was calculated by comparison to the growth of parasites grown with the DMSO controls from each plate. SID 17387000[2] was included in each assay as a positive control. Dose-response curves performed in triplicate for compounds that elicited > 50% growth inhibition at 10 μM were pursued in a 384-well plate format, with 50% effective concentrations (i.e. EC50) determined using GraphPad Prism (version 6.0) software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

We first tested the BABA analogs 2, 3, 11, and 12 against both the enzyme (rTbHK1 isolated from Escherichia coli or yeast) and live parasites (tests run in triplicate). Recall that ML205 2 is a potent inhibitor of rTbHK1 (IC50 = 0.98 ± 0.067 μM), but exhibits poor efficacy against live BSF parasites (6.9 ± 3.0 % inhibition of BSF T. brucei growth) (entry 1).6 Similarly, diacid analog 3 inhibits rTbHK1 with an IC50 of 3.5 ± 0.3 μM, but only marginally inhibits the growth of BSF parasites (51.0 ± 14.3%) (entry 2).13 The mixed diester analog 11 was ineffective against the rTbHK1 enzyme and in the assay with live BSF parasites (entry 3). Monoacid 12, our target molecule for PTS1 conjugation, was effective against the rTbHK1 enzyme (87.1 ± 3.5% inhibition at 10 μM), yet showed weak activity against the BSF parasite (24.5 ± 6.8% growth inhibition).

Thus, most of the BABA derivatives prepared in this study are reasonably active against the purified rTbHK1 enzyme but lack efficacy against the whole-cell BSF parasite. Next, we evaluated the PTS1-BABA conjugates 4–7 against rTbHK1 and against BSF T. brucei. PTS-1 BABA methyl ester 4 and acid 5 (both attached to the PTS1 via an intervening diglycine linker) were essentially inactive. Conjugate 4, did not inhibit rTbHK1 or live BSF trypanosomes at 10 μM (entry 5). Similarly, the corresponding acid 5 was a weak inhibitor of rTbHK1 (26.3 ± 3.8% at 10 μM) and was ineffective against BSF trypanosomes at 10 μM (entry 6).

In contrast to the diglycine linked PTS1-BABA conjugates, the biological evaluation of the diethylene glycol linked PTS1-BABA ester 6 and acid 7 yielded an interesting dichotomy. The methyl ester PTS1-BABA conjugate 6, while exhibiting little activity toward rTBHK1 (10.5 ± 3.6% inhibition at 10 μM), proved to be a potent inhibitor of BSF T. brucei (100% inhibition at 10 μM; BSF EC50 = 6.8 ± 1.5 μM) (entry 7, highlighted in blue). In sharp contrast, the corresponding acid 7 was reasonably effective at inhibiting rTbHK1 (67 ± 4.6% inhibition at 10 μM; IC50 = 6.8 ± 0.2 μM), yet exhibited significantly poorer efficacy against BSF parasites in culture (38.9 ± 11.1% inhibition at 10 μM) (entry 8). In addition to the compounds denoted in Table 1, we also assayed a PTS peptide sequence that lacked a drug moiety to demonstrate that the targeting sequence itself was non-toxic. Thus a PTS tripeptide bearing a fluorescein isothiocyanate moiety instead of the BABA drug conjugate was found to exhibit no toxicity to trypanosomes at 10 μM nor did it detectably inhibit the TbHK1 enzyme in vitro (see ESI for structure and data), despite effectively localizing into the glycosomes as judged by fluorescence imaging as previously described.10 Finally, we sought to benchmark our new PTS-BABA conjugates to a well-known and clinically relevant anti-trypanosomal drug, pentamadine (see ESI for structure). In our hands, pentamadine returned an EC50 of 0.003 ± 0.001 μM against BSF parasites. This value is in reasonable agreement with results reported previously by others for pentamadine against the two human-infective subspecies of T. brucei,16 and points to the potency we aim to achieve through the further development and optimization of future PTS tripeptide-drug conjugates.

Several conclusions from these results warrant emphasis. First, the data depicted in entry 7 demonstrates the success of our approach toward rescuing the trypanocidal potency of the potent rTbHK1 inhibitor 3 by appending a peroxisomal targeting sequence to the drug scaffold. Nonetheless, it is interesting that the enhanced efficacy of 6 against live BSF parasites is accompanied by a significant reduction in potency against rTbHK1 in vitro. This seemingly strange dichotomy may in fact indicate that the PTS1-BABA methyl ester conjugate 6 acts as a pro-drug, whose biologically active form (PTS1-BABA acid 7 perhaps) is only revealed upon arrival, or en route to, the glycosomal target after PTS-1 mediated passage across the cell membrane. The data for PTS1-BABA acid 7 supports this hypothesis (entry 8). The carboxylic acid of the benzamidobenzoic acid core in conjugate 7 allows for reasonably potent rTbHK1 inhibition, but may preclude passage across the cell membrane, despite the presence of the PTS-1 tripeptide. The data presented in Table 1 highlights the potential utility of this synthetically simple approach to further lead optimization of potent in vitro enzyme inhibitors by ensuring proper targeted delivery to the appropriate cellular target in vivo.

In an effort to demonstrate that localization to the trypanosome glycosome is facilitated by appending a PTS-1 tripeptide to a drug candidate, we prepared conjugate 13 (Figure 2). This molecule is essentially identical to the acitive conjugate 6, except that the side-chain amine of the lysine residue in the PTS sequence has been modified with a FITC fluorophore that facilitated cellular imaging.

Figure 2.

Localization of conjugate 13 into the glycosome of BSF T. brucei. Top row from left to right: DIC image of live procyclic form (PF) T. brucei; PTS2-mCherry localized into glycosomes of PF T. brucei; Green fluorescent PTS1-FITC-BABA conjugate 13 localized into glycosomes of PF T. brucei; merged images of PTS2-mCherry and 13 localized into glycosomes of PF T. brucei (orange hue indicates overlap). Bottom row from left to right: DIC image of live bloodstream form (BSF) T. brucei;; PTS2-mCherry localized into glycosomes of PF T. brucei; Green fluorescent PTS1-FITC-BABA conjugate 13 localized into glycosomes of BSF T. brucei; merged images of PTS2-mCherry and 13 localized into glycosomes of BSF T. brucei (orange hue indicates overlap). Scale bar = 5 μm

Thus, we imaged live procyclic form (PF) and BSF T. brucei expressing PTS2-mCherry from the tubulin locus17 (in the presence of 13). The majority of the FITC signal co-localized with the glycosome marker protein (PTS2-mCherry). These findings suggest that in living parasites, the PTS-1 modified cargo was delivered to the appropriate subcellular compartment. The activity of conjugate 6 against enzyme and the distribution of its fluorescent analog 13 in live trypanosomes, suggests that the toxicity observed in the parasites for 6 may be in part due to inhibition of the essential hexokinase activity in vivo.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have successfully prepared a series of PTS1-BABA conjugates and evaluated their potency as inhibitors of recombinant T. brucei hexokinase 1 (rTbHK1) and as trypanocides against live BSF T. brucei. In doing so, we have demonstrated that appending the PTS1 tripeptide can rescue the poor trypanocidal efficacy of an otherwise potent inhibitor of rTbHK1. To the best of our knowledge, these results represent the first example of the successful delivery of a drug candidate to the glycosome of a kinetoplastid parasite facilitated by the incorporation of a simple targeting sequence through straight-forward synthetic operations. This strategy represents a complementary strategy for the development of potent trypanocides that does not rely on conventional medicinal chemistry derivitization of the parent scaffold. Further, we have shown that the PTS1-BABA conjugates are efficiently localized within the glycosome of PF and BSF parasites by means of fluorescence microscopy. We have confirmed for the first time that PTS1 mediated drug delivery is possible in trypanosomatids. Further, we suspect that the PTS1 conjugation strategy for drug delivery described herein could be applicable to other members of the family, including T. cruzi and Leishmania major, the causative agents of Chagas disease and leishmaniasis, respectively. Efforts to demonstrate the broader efficacy of this strategy with other trypanosomatids and to develop molecular probes to understand the cellular mechanisms for PTS1 mediated uptake in trypanosomes are underway.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of PTS1-BABA conjugates 3–6.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Clemson University Department of Chemistry and Department of Genetics and Biochemistry for their financial support of this work. Work in the JCM laboratory was partially supported by a Center for Biomedical Excellence (COBRE) grant of the National Institutes of Health under award number P20GM109094. Work in the JCM and KAC labs were partially supported by an award from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (R21AI105656). Additionally, the Clemson University Honors College and the Clemson University Creative Inquiry Program are thanked for their support. The authors thank Artita Sarkar for assistance with HRMS analysis.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Full experimental details and physical data for all new compounds. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.a.) Hide G. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:112–125. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b.) Beard CB. Emerging Infect Dis. 2009;15:510–511l. doi: 10.3201/eid1503.081060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c.) Barrett MP, Burchmore RJS, Stich A, Lazzari JO, Frasch AC, Cazzulo JJ, Krishna S. Lancet. 2003;362:1469–1480. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14694-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharlow ER, Lyda TA, Dodson HC, Mustata G, Morris MT, Leimgruber SS, Lee KH, Kashiwada Y, Close D, Lazo JS, Morris JC. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(4):e 659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joice AC, Harris MT, Kahney EW, Dodson HC, Maselli AG, Whitehead DC, Morris JC. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2013;3:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nwagwu M, Opperdoes FR. Acta Trop. 1982;39:61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers JW, Fowler ML, Morris MT, Morris JC. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;158:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharlow E, Golden JE, Dodson H, Morris M, Hesser M, Lyda T, Leimgruber S, Schroeder CE, Flaherty DP, Weiner WS, Simpson D, Lazo JS, Aube J, Morris JC. Identification of inhibitors of Trypanosoma brucei hexokinases” (2010, updated 2011) Probe Report from the NIH Molecular Libraries Program National Center for Biotechnology Information. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodson HC, Morris MT, Morris J JC. Biol Chem. 2011;286:33150–33157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.235705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milagros Camara MdL, Bouvier LA, Miranda MR, Pereira CA. Exp Parasitol. 2012;130:408–411. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa-Pinto D, Trindade LS, McMahon-Pratt D, Traub-Cseko YM. Int J Parisitol. 2001;31:536–543. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin S, Morris MT, Ackroyd PC, Morris JC, Christensen KA. Biochemistry. 2013;52:3629–3637. doi: 10.1021/bi400029m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elmore CS, Dean DC, DeVita RJ, Melillo DG. J Label Compd Radiopharm. 2003;46:993–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daugan ACM, Mirguet O, Lamotte Y. US 20130345212A1. Quinolinone Derivatives US Patent. 2013 Dec 26;

- 13.Flaherty DP, Harris MT, Schroeder CE, Khan H, Kahney EW, Hackler AL, Patrick SL, Weiner WS, Aubé J, Sharlow ER, Morris JC, Golden JE. Manuscript in preparation. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201700592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hood CA, Fuentes G, Patel H, Page K, Menakuru M, Park JH. J Pept Sci. 2008;14:97–101. doi: 10.1002/psc.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fields GB, Noble RL. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1990;35:161–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1990.tb00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raz B, Iten M, Gether-Buhler Y, Kaminsky R, Brun R. Acta Trop. 1997;68:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(97)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodson HC, Lyda TA, Chambers JW, Morris MT, Christensen KA, Morris JC. Exp Parasitol. 2011;127:423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.