Abstract

Objectives

This study explores Chinese cervical cancer survivors’ perceived cognitive complaints and relevant supportive care needs after primary cancer treatment.

Design

This study utilised a qualitative research design. A semi-structured interview was used to probe cervical cancer patients’ perceived cognitive complaints and supportive care needs.

Setting

This study was conducted at a secondary cancer care centre located in South China.

Participants

31 women with cervical cancer after primary cancer treatment, aged 18–60 years, were purposively selected using non-random sampling procedures.

Results

31 cervical cancer survivors joined this study. Of these, 20 women (64.5%) reported cognitive complaints after cancer treatment. The most common complaint was loss of concentration (n=17, 85.0%). Perceived contributing factors to these cognitive complaints included chemotherapy (n=15, 75.0%) and ageing (n=8, 40.0%). These cognitive problems most commonly impacted daily living (n=20, 100%). Common supportive care needs included symptom management strategies (n=11, 55.0%) and counselling services (n=8, 40.0%).

Conclusion

This study adds new insight into the growing body of research on cognitive complaints by cancer survivors, in particular Chinese cervical cancer survivors. Improved understanding of cognitive complaints could subsequently facilitate the development of relevant therapeutic interventions for prevention as well as the provision of supportive care services, such as educational and counselling services, to reduce cognitive impairment in women with cervical cancer.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Survivors, Cognitive complaints, Supportive care needs

Study strengths and limitations.

This qualitative study used written responses as a means of data collection, which is a more cost effective and less time consuming method as it does not require transcription.

An additional study strength is that written qualitative responses overcame the Chinese dialect barrier, as Chinese people, even within the same province, typically speak many different dialects. The written language is understandable across all dialect groups.

This preliminary study recruited participants at a single medical centre, which could limit the transferability of the study findings.

This study included participants who had completed primary cancer treatment within a short time frame; longitudinal research should be conducted to identify the trajectory of cognitive complaints over the cancer care continuum.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer, followed by breast cancer, among women in China.1 Due to medical advancements in early detection and the possibility of curative cancer treatment,2 the 5 year relative survival rate of cervical cancer in mainland China is up to 69% for all stages.1 As more cervical cancer survivors are living longer after curative treatment, the late effects of cancer treatment are becoming increasingly common.3 One such long term and late effect is neurocognitive, which has emerged as a significant problem affecting cervical cancer survivors.4 5

Cognitive complaints often refer to cognitive impairment or cancer related cognitive impairment.6 7 Other studies have described this as chemotherapy related cognitive dysfunction, colloquially named ‘chemo brain’ or ‘chemo fog’.8 9 Cognitive complaints have the potential to significantly impact both social and occupational functioning, interfering with the ability to carry out normal daily activities, all of which can contribute to lower quality of life (QOL) for cancer survivors.4 6 10 Cognitive complaints have been reported in approximately 40% of patients prior to any cancer treatment, and as many as 75% of patients indicate some degree of cognitive impairment during the period of active cancer treatment. Finally, cognitive complaints are still present in up to 60% of long term cancer survivors.6 In a study conducted in mainland China, female cancer survivors with an average of 2.79 years post-primary treatment reported higher levels of cognitive limitations, significantly reducing their work productivity and global QOL.11

Quantitative research approaches are used to explore cognitive complaints and related supportive care issues among cancer survivors,4 12 with researchers proposing that quantitative cognitive measures are more objective and reliable than qualitative exploration of cognitive problems in cancer survivors.13 14 However, other researchers have argued there are inherent difficulties with a quantitative approach, in terms of fully appreciating cancer patients’ cognitive complaints.4 15 Qualitative research studies would enable us to identify the presence of cognitive symptoms that quantitative approaches cannot detect, either by self-reported cognitive measures or neurocognitive tests.15 In addition, qualitative in-depth interviews could provide information about how cognitive impairment impacts cancer patients’ QOL, and could allow researchers to obtain information about the numerous coping strategies to ameliorate cognitive dysfunction symptoms, as well as to develop intervention strategies.15

Therefore, there is a need for a qualitative study to explore the perceived cognitive complaints and relevant supportive care needs of cervical cancer survivors after primary cancer treatment. A clear understanding of the cognitive complaints experienced by cervical cancer survivors, through qualitative in-depth interviews, could aid healthcare providers in developing targeted interventions, as well as in providing relevant supportive care services to alleviate the extent and impact of cancer survivors’ cognitive complaints.16

Methods

Design

The study utilised a qualitative research design. A semi-structured interview was used to probe cervical cancer patients’ perceived cognitive complaints and supportive care needs.

Study framework

This study was guided by the conceptual model of chemotherapy related changes in cognitive function proposed by Myers.17 This model consists of three key components: antecedents (cancer diagnosis and cancer treatment), mediators (physiological, psychosocial and situational factors) and consequences (QOL and functional ability).17 While this model is described as chemotherapy related cognitive impairment, recent evidence indicates that cancer itself is also related to cognitive impairment.6 As suggested by Myers, when researchers learn more about the physiological and psychological aspects of cognitive impairment, this model will require refining.17

Study sample

All study participants were recruited from the gynaecological oncology unit in a cancer hospital. Ethics approval was obtained from the hospital’s ethics committee. A purposive sampling was drawn to recruit eligible informants. Inclusion criteria were: women who were at least 18 years old, with a primary diagnosis of cervical cancer and who had completed their primary cancer treatment of surgery, radiation therapy or chemotherapy. Exclusion criteria included potential psychiatric disorders, previous cancer history or traumatic brain injury.

Study procedure and qualitative interviews

After obtaining ethics approval, participants were recruited from the hospital’s gynaecological inpatient department. One of the authors assessed the eligibility of the participants. Eligible women were invited to the hospital’s meeting room to complete the semi-structured interview individually. Eligible participants were asked to participate in a semi-structured interview, and complete a sociodemographic sheet. This sheet was used to collect information on demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, education level, marital status, tumour stage, type of cancer treatment received and time since completion of primary cancer treatment. Qualitative interviews were guided by a narrative epistemology to encourage participants to provide narrative accounts of their perceived experience.18 The author who conducted the interviews is a nursing professor who holds a Master of nursing degree. All researchers in this study have been conducting clinical research for more than 5 years, and all have qualitative research training. The interviewer was an experienced research nurse who was not a staff nurse in the research setting of the gynaecological oncology unit. The data collection method was by written narrative, so that the interviewer's beliefs, biases and preconceptions had no influence on the direction of the interviews. There were no non-participants present in the interviews, and the interviewer only remained in the meeting room to take field notes to capture any emerging thoughts to guide data analysis.

The interviews were conducted face to face in the inpatient ward’s meeting room. All interviews used an interview guide comprised of the following open ended questions. (1) Compared with before your cancer diagnosis, tell us about the overall change in your cognitive abilities? For example, your perceptions of understanding of what people say to you; thinking of the right word when responding to others; and feeling confident about completing a task or taking on new tasks. (2) What do you think the common contributing factors to any cognitive changes might be? (3) How do these perceived cognitive changes impact on your daily life or your ability to work? (4) How do you deal with these changes? In other words, what types of coping strategies do you use as a result of any cognitive changes you might be experiencing? (5) What types of supportive care services do you need from healthcare providers, to help you cope with any cognitive complaints?

Each interview lasted 30–45 min, and was recorded by a digital recorder and transcribed verbatim. Data saturation was achieved much earlier than the final sample size of 31 patients, as data collection and analysis were performed simultaneously in an iterative process.19

Data analysis

Qualitative interview data were transcribed to produce a verbatim transcript. During the entire data analysis process, the researcher consciously separated herself from personal biases, in order to be open to the information shared by the study participants. NVivo 11 qualitative software (http://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-product/nvivo11-for-windows) was applied to organise and code the verbatim transcript. Qualitative content analysis was used to prepare, organise and report the data.20 A three step content analysis process was followed. (1) The verbatim transcript was organised into meaning units (such as words, phrases, sentences or paragraphs that conveyed similar content deemed important in understanding patients' experiences). (2) The meaning units were coded and categorised. (3) The abstraction process was guided by Myers's conceptual model and continued until primary themes were identified.20

Two research members conducted content analysis independently. In the event of any disagreement with the interpretation of clusters or categories, a third research member was involved in the discussion process to establish a consensus. To ensure the study findings were accurately reflecting informants' truly perceived experiences of cognitive changes, three research participants were invited to check the final verbatim transcript for the purpose of collecting participants' feedback and validation. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) checklist was applied to guide this study and ensure study rigour (see online upplementary appendix 1).21

bmjopen-2016-014078supp001.pdf (18.7KB, pdf)

Results

A total of 50 patients with cervical cancer were approached, with 31 agreeing to participate in this written narrative interview. Those who did not participate in this study had no interest in participating in any type of research. Their characteristics in terms of age, cancer stage and treatment types were comparable with the patients who completed the semi-structured interviews. Of the 31 participants, 20 women (64.5%) reported cognitive complaints after cancer treatment. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the women with and without perceived cognitive impairment are listed in table 1. From table 1, the demographic/clinical characteristics of women with and without perceived cognitive impairment were comparable.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with and without cognitive impairment

| Variable | Number (%) | |

| With reported cognitive impairment (n=20) | Without reported cognitive impairment (n=11) | |

| Age (years) (mean (SD) (range)) | 46.40 (9.80) (19–57) | 43.45 (12.08) (19–56) |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary school or below | 11 (55.0) | 5 (45.5) |

| College | 6 (30.0) | 5 (45.5) |

| University or above | 3 (15.0) | 1 (9.0) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed but on medical leave | 10 (50.0) | 7 (63.6) |

| Unemployed or retired | 10 (50.0) | 4 (36.4) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 19 (95.0) | 10 (90.9) |

| Divorced | 1 (5.0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Disease stage | ||

| Stage IA | 7 (35.0) | 4 (36.4) |

| Stage IB-IIA | 11 (55.0) | 6 (54.5) |

| Stage IIB-IVA | 2 (10.0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Type of treatment | ||

| Surgery | 5 (25.0) | 3 (27.3) |

| Surgery+chemotherapy | 5 (25.0) | 4 (36.4) |

| Surgery+radiation therapy | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Surgery+radiation+chemotherapy | 6 (30.0) | 2 (18.2) |

| Radiation or chemotherapy | 2 (10.0) | 2 (18.2) |

| Time since completion of primary treatment (months) (mean (SD) range)) |

1.70 (1.03) (1–5) | 1.63 (1.20) (1–5) |

Major categories that emerged from the data, including cognitive complaints, perceived contributing factors, impact of cognitive problems on women’s daily lives, health outcomes and work capabilities, coping strategies and patients’ supportive care needs from healthcare providers, are shown in table 2. The most common complaint was loss of concentration (n=17, 85.0%) followed by memory problems (n=15, 75.0%). Other common cognitive complaints included difficulties in learning, language issues (finding the right words in everyday conversations) and a slowed rate of information processing.

Table 2.

Major categories from the qualitative content analysis (n=20)

| Category | n (%) | Illustrative quotes from participants |

| Cognitive complaints | ||

| Lost concentration | 17 (85.0) | It’s difficult to focus on a conversation or when reading newspapers or books. My biggest problem is lack of concentration |

| Easily forgetting things or information from others | 15 (75.0) | My memory changed a lot after chemotherapy; when I meet my friend on the street, I can’t even remember her name. Sometimes, nurses tell me information about the illness, and I can’t even remember what they have just told me |

| Feeling it’s hard to understand new things | 7 (35.0) | When I was reading books, I saw the words, but I could not make sense of the words, even when I read the same sentence several times |

| Difficulties in finding right word in general conversation | 4 (20.0) | When I speak with someone in general conversation, it’s hard for me to find the right words |

| Slowing down in working efficiency compared with how they used to be | 2 (10.0) | I was used to being well organised in my work and daily life, but now it’s hard to get back all those abilities, and work has slowed down a lot |

| Perceived causative factors | ||

| Relating to chemotherapy | 15 (75.0) | Even during chemotherapy, I found that my memory changed a lot. Now I have completed the whole cycle of chemotherapy, and more and more memory impairment has appeared |

| Side effects of cancer and its treatment | 12 (60.0) | I believe that a lot of physical examinations, such as CT at the time of diagnosis, the use of analgesics and the surgery procedure are all related to my cognitive problems |

| Ageing | 8 (40.0) | Maybe due to my age, my memory is worse and I’ve started forgetting things quickly |

| Psychosocial issues | 3 (15.0) | Having to deal with too many sources of stress, such as the financial issues related to medical treatment |

| Relating to immune function | 2 (10.0) | After I got this disease and received this series of cancer treatments, my immune function was destroyed, so my memory problems are partly due to this |

| Coping strategies | ||

| Writing memos | 15 (75.0) | Writing down important things, use of diaries or phone reminders to organise daily tasks |

| Self-adjustment and relaxation techniques | 14 (70.0) | Asking myself to focus on one task at a time. When disturbed by other things or people, I’ll adjust myself and refocus on what I was doing. By reading, or listening to music for focus |

| Doing nothing | 6 (30.0) | Now I can do nothing for this problem (cognitive impairment), as this may be due to my age; with older age, cognitive decline appears naturally. Other patients believe these cognitive problems are reversible and may get better gradually |

| Environment organisation | 2 (10.0) | To keep important personal belongs such as keys, eyeglasses, mobile phone in a fixed place |

| TCM such as acupuncture | 1 (5.0) | Doctors told me there were no effective drug therapies for this problem, so I tried acupuncture |

| Supportive care needs from healthcare providers | ||

| Providing common symptoms of cognitive impairment and its effective therapies | 11 (55.0) | It’s great for doctors and nurses to tell me about common signs or symptoms of cognitive impairment, and to provide intervention therapies to treat these problems |

| Providing counselling services to family members | 8 (40.0) | It’s hard for me to remember so much information. Healthcare providers should provide educational information and more counselling services to my family members |

| Need information about possible rehabilitation service | 7 (35.0) | After hospital discharge, where should I seek further rehabilitation service for cognitive problems? Or can I gradually recover from these problems? |

| Offering peer support networks | 2 (10.0) | At the time of diagnosis and during cancer treatment, I felt so worried. I need to connect with women who have had a similar experience, in order to share coping strategies |

| Impact on | ||

| Daily life | 20 (100) | Sometimes, when people speak with me, I immediately forget what they were talking about, or when I’m doing things and people interrupt me, I’ll forget what I wanted to do |

| Quality of life | 9 (45.0) | This disease and its treatment have severely impacted all aspects of my life, and have left me feeling overwhelmed. Now I have a poor memory, slowed thinking process and a large financial burden as a result of the medical costs, causing tension in my family relationship |

| Psychological health | 5 (25.0) | Sometimes my brain becomes a blank, and it seems my memory is not coming back, so I feel really scared |

| Work capability | 3 (15.0) | I have to leave my job, due to my body image now, during and after chemotherapy I lost a lot of hair, and I can’t work for very long, I can only work for a short period of time, then I have to rest |

| Physical health conditions | 2 (10.0) | Cognitive function changes were not obvious, but my health condition was a lot worse; before the cancer diagnosis, my health was OK. But now my sleep is not good, my immune system is much weaker, and due to the loss of physical energy I can’t work too long and need to take a break after working for just a short while |

TCM, traditional Chinese medicine.

The participants identified several factors that they believed were contributing to their cognitive complaints, including chemotherapy (n=15, 75.0%), side effects of cancer and other treatments, such as surgery or radiation therapy (n=12, 60.0%), and ageing (n=8, 40.0%). These cognitive complaints had a negative impact on daily life, sleep and rest (n=20, 100%). Two participants indicated their cognitive function had seen negligible change, but their physical health had deteriorated significantly after the diagnosis of cervical cancer. While 10 women were on medical leave at the time of data collection, two women indicated they were planning to leave their jobs due to loss of concentration and slowed information processing capacity.

As shown in table 2, the most commonly used coping strategies were memo writing (n=15, 75.0%) and self-adjustment (n=14, 70.0%). Other coping strategies included ‘doing nothing’ and organisation of their environment. In addition, one woman sought acupuncture as an alternative therapy, after her physician told her there was no effective medication for cognitive impairment. Chinese cervical cancer survivors described a variety of supportive care requirements: patient, as well as family, education on the common signs and symptoms of cognitive impairment; effective treatment therapies (n=11, 55.0%); counselling for family members (n=8, 40.0%); and information on further rehabilitation services (n=7, 35.0%). Two women expressed the need for peer support, and suggested that healthcare providers could organise a peer support group for patients starting from the diagnosis stage onwards. Several patients indicated that their healthcare providers had never mentioned the potential for cognitive impairment, and only addressed this when patients asked about cognitive problems that appeared during cancer treatment.

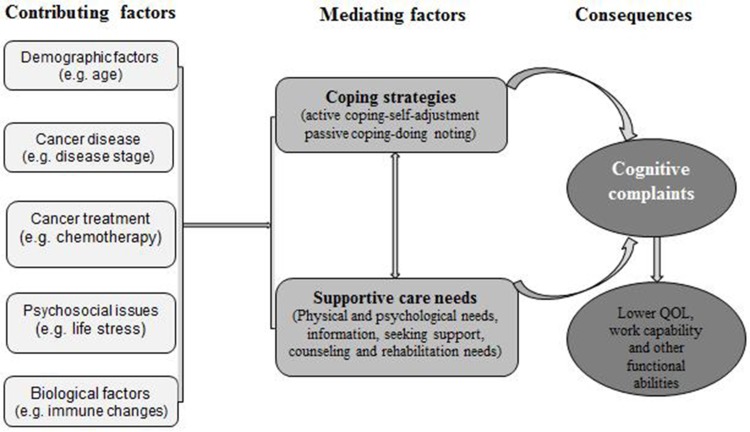

Based on the conceptual model of chemotherapy related changes in cognitive function proposed by Myers (2009), and in combination with a synthesis of these qualitative findings, a new cognition model among cervical cancer survivors is illustrated in figure 1. Cognitive complaints are multifactorial in nature, with contributing factors that include demographic characteristics, biological factors, psychological distress, disease stage and cancer therapies.

Figure 1.

Preliminary cognition model among cervical cancer survivors after cancer treatment.

Discussion

This is one of the first published studies exploring cognitive complaints among Chinese cervical cancer survivors. There is accumulating evidence documenting cognitive impairment issues among cancer survivors, but this is mainly dominated by breast cancer survivors.22 The prevalence of cognitive complaints among Chinese cervical cancer survivors was 64.5%, which is consistent with previous research.6 As this study was preliminary and adopted a small and non-random sample, epidemiological studies are needed to further quantify the prevalence, impact and extent of cognitive complaints in this study population.23

Concurring with previous research evidence, chemotherapy and the side effects of cancer are the most common factors associated with cognitive complaints.4 7 This study identified that cervical cancer survivors perceive ageing as a likely contributing factor to cognitive impairment. Study participants considered ‘ageing as a normal process of cognitive decline’ and viewed cognitive impairment as a process that could not be changed. Consistent with previous studies,17 24 study participants also reported that worry, fatigue and pain all seem to be related to cognitive impairment.

The patient experience of cancer related cognitive impairment may be the commonality of the phenomenon across tumour types,25 as this study did not find unique cognitive deficits in women with cervical cancer. However, the study did identify unique cultural issues for Chinese women seeking coping strategies for cognitive impairment. Some women did nothing to try to cope with their cognitive complaints. ‘Doing nothing’ as a common coping strategy for cognitive complaints could be related to the Chinese Taoist philosophy: ‘Accepting the fact that a situation cannot be changed, and telling oneself that one should do little, as things will be all right at the end of the day’.26 Hence a coping strategy of doing nothing and self-adjustment could help these survivors maintain a sense of calm when facing difficulties that cannot be changed.

As in previous studies,4 6 7 this study’s findings also revealed that cognitive complaints had a variety of consequences that impacted on daily living, QOL, physical and psychological health, and work capabilities. While research into the relationship between cognitive functioning and ability to work is still in its infancy,27 returning to work is a critical milestone for many survivors, as work plays a key role in psychological, economic and social well being.28 If cancer survivors were able to obtain individualised support and work related adjustments from their employer, they would be more likely to continue working.23 Hence cognitive complaints in cancer survivors generate numerous supportive care requirements, not only in the workplace, but also from healthcare providers.

Common supportive care needs that patients require from healthcare providers include the provision of information on the common signs of cognitive impairment, as well as management strategies, effective treatment therapies and possible rehabilitation services, in order to manage cognitive problems. Although many healthcare providers may gloss over the issue of patient cognitive complaints, believing they have no curative treatment to offer patients,29 findings from a meta-analysis indicate that neuropsychological interventions (cognitive rehabilitation, cognitive training and neuromodulation strategies) can improve cognitive function in cancer survivors.30 In particular, a recent Cochrane review indicated that cognitive training may be effective in improving patients' cognitive function, as well as their QOL.31 Additionally, behavioural intervention strategies (increasing physical activity levels and fostering supportive social relationships) could be helpful in improving cognitive function among cancer survivors.12

Through a synthesis of these study findings, a preliminary cognition model for cervical cancer survivors after cancer treatment was established, to provide a theoretical underpinning for the perception of cognitive complaints, contributing factors, mediating factors and the consequences of cognitive impairment in this study population. This model may be able to inform and stimulate further intervention studies. Certainly, this preliminary cognition model can be continuously refined through further empirical research investigations. Overall, this model illustrates coping strategies at a personal level, through self-adjustment or by doing nothing. Additionally, supportive care services, such as education and counselling for family members, could mitigate the consequences of cognitive impairment. In addition, participants felt a great need for support, including peer support, from diagnosis onwards, as well as for information on available rehabilitation services and counselling, in order to modulate the degree of cognitive complaints. For survivors of cervical cancer, cognitive complaints exert negative effects on daily living, QOL, work capability, and physical and psychological health.

Limitations and implications for future research

This preliminary study has two limitations. First, this study only recruited participants at a single medical centre, and the sample size is not representative of this population in general. This study primarily offers significant insights into perceived cognitive complaints, contributing factors and consequences of cognitive impairment in cervical cancer survivors. Second, this study utilised a cross sectional design and included participants who had completed primary cancer treatment within a short period of time. Future longitudinal research should be conducted to identify the trajectory of cognitive complaints over the cancer care continuum. As Myers suggested,25 qualitative studies provide valuable information for healthcare professionals on the impact of cognitive changes on cancer patients’ QOL and activities of daily living. Understanding cancer patients' experiences of cognitive impairment, their coping strategies and supportive care needs could help healthcare professionals develop interventions to prevent, mitigate and treat the cognitive sequelae of cancer and its treatment therapies.25

Conclusion

This study adds new insight into the growing body of research on cognitive complaints by cancer survivors, in particular Chinese survivors of cervical cancer. Improved understanding of cognitive complaints could subsequently facilitate the development of relevant therapeutic interventions for prevention, as well as for the provision of supportive care services such as education and counselling, to reduce cognitive impairment in women with cervical cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all participants who voluntarily joined this study and generously shared their views and concerns.

Footnotes

Contributors: YZ and ASKC are the main authors, and designed this study and drafted this manuscript. XL conducted the interviews, and XL and YZ analyzed the data independently. CCHC made significant contributions to the manuscript revisions.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of Hunan Cancer Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We are glad to share data collected in this study upon written request.

References

- 1. Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. . Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:115–32. 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lange M, Rigal O, Clarisse B, et al. . Cognitive dysfunctions in elderly Cancer patients: a new challenge for oncologists. Cancer Treat Rev 2014;40:810–7. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Treanor CJ, Donnelly M. The late effects of cancer and cancer treatment: a rapid review. J Community Support Oncol 2014;12:137–48. 10.12788/jcso.0035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Craig CD, Monk BJ, Farley JH, et al. . Cognitive impairment in gynecologic cancers: a systematic review of current approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:279–87. 10.1007/s00520-013-2029-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Faubion SS, MacLaughlin KL, Long ME, et al. . Surveillance and care of the gynecologic cancer survivor. J Womens Health 2015;24:899–906. 10.1089/jwh.2014.5127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wefel JS, Kesler SR, Noll KR, et al. . Clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management of noncentral nervous system cancer-related cognitive impairment in adults. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:123–38. 10.3322/caac.21258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Janelsins MC, Kesler SR, Ahles TA, et al. . Prevalence, mechanisms, and management of cancer-related cognitive impairment. Int Rev Psychiatry 2014;26:102–13. 10.3109/09540261.2013.864260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wefel JS, Schagen SB. Chemotherapy-related cognitive dysfunction. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2012;12:267–75. 10.1007/s11910-012-0264-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hines S, Ramis MA, Pike S, et al. . The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for cognitive dysfunction in cancer patients who have received chemotherapy: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2014;11:187–93. 10.1111/wvn.12042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Correa DD, Hess LM. Cognitive function and quality of life in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2012;124:404–9. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zeng Y. Symptom profiles, work productivity and quality of life among Chinese female cancer survivors. Gynecology & Obstetrics 2016;06:357. 10.4172/2161-0932.1000357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Henneghan A. Modifiable factors and cognitive dysfunction in breast cancer survivors: a mixed-method systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:481–97. 10.1007/s00520-015-2927-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dutta V. Chemotherapy, neurotoxicity, and cognitive changes in breast cancer. J Cancer Res Ther 2011;7:264–9. 10.4103/0973-1482.87008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hess LM, Chambers SK, Hatch K, et al. . Pilot study of the prospective identification of changes in cognitive function during chemotherapy treatment for advanced ovarian Cancer. J Support Oncol 2010;8:252–8. 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu LM, Tanenbaum ML, Dijkers MP, et al. . Cognitive and neurobehavioral symptoms in patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy or observation: a mixed methods study. Soc Sci Med 2016;156:80–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boykoff N, Moieni M, Subramanian SK. Confronting chemobrain: an in-depth look at survivors' reports of impact on work, social networks, and health care response. J Cancer Surviv 2009;3:223–32. 10.1007/s11764-009-0098-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Myers JS. A comparison of the theory of unpleasant symptoms and the conceptual model of chemotherapy-related changes in cognitive function. Oncol Nurs Forum 2009;36:E1–E10. 10.1188/09.ONF.E1-E10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Benzein E, Norberg A, Saveman BI. The meaning of the lived experience of hope in patients with cancer in palliative home care. Palliat Med 2001;15:117–26. 10.1191/026921601675617254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Von Ah D. Cognitive changes associated with cancer and cancer treatment: state of the science. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2015;19:47–56. 10.1188/15.CJON.19-01AP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheung YT, Shwe M, Tan YP, et al. . Cognitive changes in multiethnic Asian breast cancer patients: a focus group study. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2547–52. 10.1093/annonc/mds029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hart RP, Wade JB, Martelli MF. Cognitive impairment in patients with chronic pain: the significance of stress. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2003;7:116–26. 10.1007/s11916-003-0021-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Myers JS. Cancer- and chemotherapy-related cognitive changes: the patient experience. Semin Oncol Nurs 2013;29:300–7. 10.1016/j.soncn.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zeng YC. E-mail interviewing Chinese hospital nurses’ interpretations of work-related stress. Asian J Nurs 2008;11:72–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Munir F, Kalawsky K, Lawrence C, et al. . Cognitive intervention for breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy: a needs analysis. Cancer Nurs 2011;34:385–92. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31820254f3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Becker H, Henneghan A, Mikan SQ. When do I get my brain back? Breast cancer survivors' experiences of cognitive problems. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2015;19:180–4. 10.1188/15.CJON.180-184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Duijts SF, van Egmond MP, Spelten E, et al. . Physical and psychosocial problems in cancer survivors beyond return to work: a systematic review. Psychooncology 2014;23:481–92. 10.1002/pon.3467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zeng Y, Cheng AS, Chan CC. Meta-analysis of the effects of neuropsychological interventions on cognitive function in non-central nervous system cancer survivors. Integr Cancer Ther 2016. 15:424–34. 10.1177/1534735416638737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Treanor CJ, McMenamin UC, O'Neill RF, et al. . Non-pharmacological interventions for cognitive impairment due to systemic cancer treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016:CD011325. 10.1002/14651858.CD011325.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014078supp001.pdf (18.7KB, pdf)