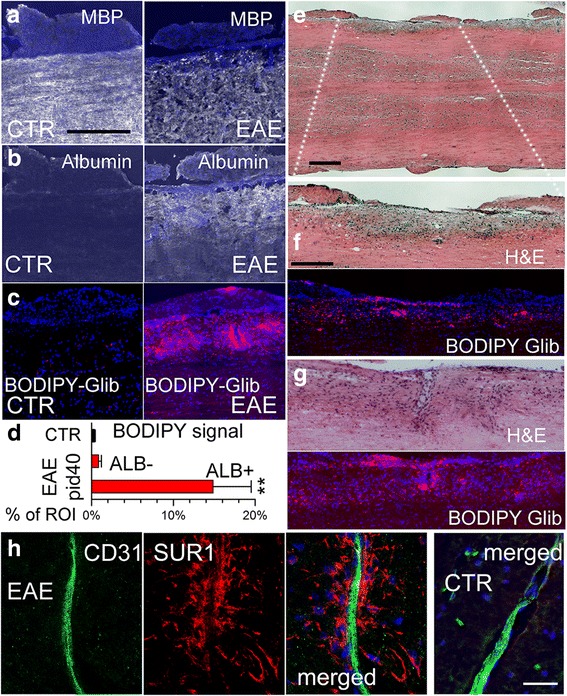

Fig. 7.

Glibenclamide enters EAE lesions in the spinal cord. a–c Sections of lumbar spinal cords from control (CTR) and EAE mice administered bodipy-glibenclamide, immunolabeled for MBP (a) or albumin (b), using an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (green signal, with signal shown as white for clarity), or imaged for intrinsic fluorescence due to bodipy (red) (c); nuclei labeled with DAPI (blue); scale bar 100 μm. d Quantification of bodipy signal in control (non-EAE) and in albumin-negative (ALB–) and albumin-positive (ALB+) regions of interest (ROI) from EAE; **P < 0.01 with respect to control (CTR). e–g Sections of lumbar spinal cords from EAE mice administered bodipy-glibenclamide, stained with H&E, illustrating a demyelinating lesion at low (e) and higher f magnification, and a non-demyelinating lesion with immune cell infiltrates (g), along with the associated intrinsic fluorescence due to bodipy (red); scale bars 200 μm. h Double immunolabeling of demyelinating lesion (3 left panels) and control tissue (right panel) for CD31 (endothelium) (green) and SUR1 (red) illustrates that SUR1 is not upregulated in endothelium but predominantly in perivascular structures typical of astrocytic endfeet; merged images are indicated; scale bars 25 μm