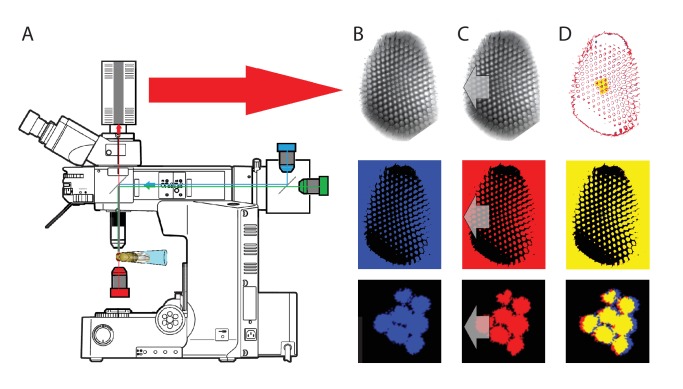

Appendix 7—figure 1. Microscope system for high-speed video recording of light-induced photoreceptor movements.

(A) High-speed camera (Andor Zyla, UK) recorded images of deep pseudopupils in the eye of an intact living Drosophila under deep-red antidromic illumination (here 740 nm LED + 720 nm long-pass edge filter underneath the fly head). Each studied fly was immobilized inside a pipette tip. (B) A 10 ms blue-green light flash, delivered through the microscope system (orthodromically) into the left fly eye (above), was used to excite R1-R8 photoreceptors; the inset below shows R1-R7 rhabdomeres (blue) of one ommatidium just before the flash. (C) Light caused the rhabdomeres to twitch photomechanically in back-to-front direction (arrows) after 8–16 ms delay, with the photoreceptors being maximally displaced in ~ 100 ms from the stimulus onset. Invariably, this was seen as a sudden jump in the recorded rhabdomere position (red). (D) The difference in the rhabdomere position (displacement) before and after the flash, depended upon the light intensity, ranging between 0.3–1.4 µm; note a typical R1-R6 rhabdomere diameter is about 1.7 µm (Appendix 5). The frame subtraction (before and after the light flash) indicates that only the rhabdomeres that aligned directly with the blue/green light source moved (within the seven central ommatidia; yellow area), while the rest of the eye remained immobile. Accordingly, the difference image shows little ommatidial walls, as these and other immobile eye structures became mostly subtracted away. In contrast, eye muscle activity, which is every so often seen with this preparation (Appendix 4, Appendix 4—figure 6) occurs more gradually and moves all the eye structures together.