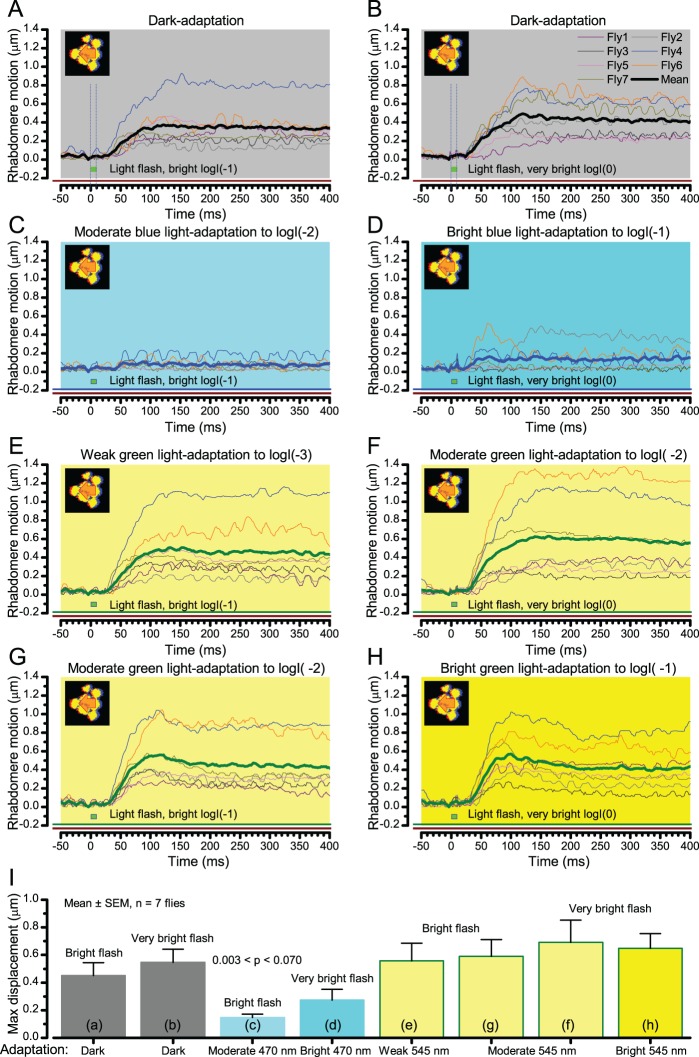

Appendix 7—figure 12. Wild-type photomechanical rhabdomere movement dynamics at different light-adaptation states.

Characteristic non-averaged photomechanical rhabdomere movements of 7 wild-type flies and their means (thick traces) to bright (logI(−1); left) or to very bright (logI(0); right) light flashes. The recordings were performed in relative darkness (>720 nm) or when the eyes were adapted for 30 s to different green (545 nm) or blue (470 nm) light intensity levels; from weak (logI(−3)) to bright (logI(−1)). (A–B) In dark-adaptation, consistent with the results in Appendix 7—figure 11, the brighter the flash, the larger and faster the evoked mean rhabdomere movements. (C–D) Prolonged blue light exposure converted virtually all Rh1-rhodopsins to their active meta-form, causing a PDA (prolonged depolarizing afterpotential). PDA increases the photoreceptors’ intracellular calcium load, cleaving PIP2 from the plasma-membrane and so keeping them in a contracted state. A very bright green flash rapidly converts some of the meta-Rh1 back to Rh1, enabling small and brief rhabdomere movements, which resemble those seen with hdcJK910 flies (Appendix 7—figure 11). (E–H) Adaptation to different green-light intensity levels did not abolish rhabdomere movements to light increments. These movements can, in fact, be larger than in the same cell’s dark-adapted state, as was seen in Fly4 and Fly6 recordings. Notice that a 1.2–1.4 µm rhabdomere displacements means ~4-5o shifts in a R1-R6 photoreceptor’s receptive field (Appendix 7—figure 4), which can be more than the average Drosophila interommatidial angle.