Abstract

Background

There are limited data regarding the risk stratification based on peak aortic jet velocity (Vmax) in patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS).

Methods and Results

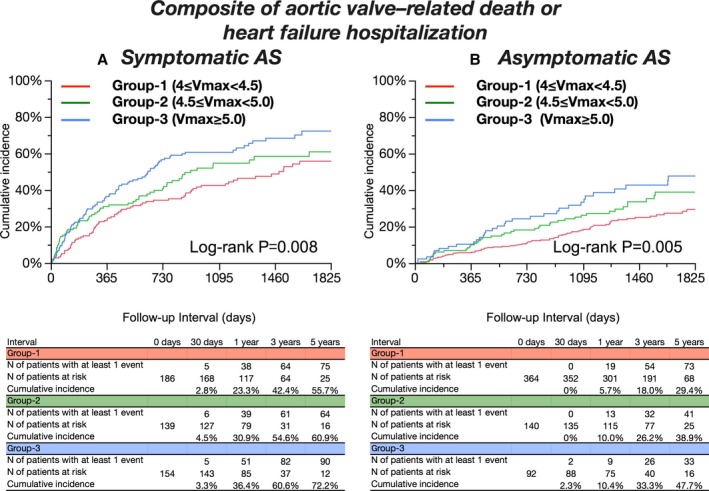

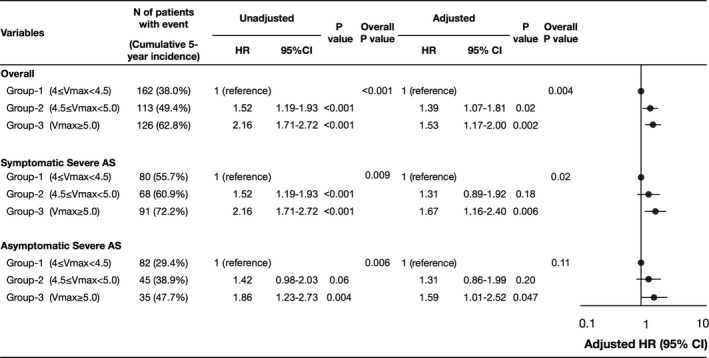

Among 3815 consecutive patients with severe AS enrolled in the CURRENT AS (Contemporary Outcomes After Surgery and Medical Treatment in Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis) registry, the study population consisted of 1075 conservatively managed patients with Vmax ≥4.0 m/s and left ventricular ejection fraction ≥50%. The study patients were subdivided into 3 groups based on Vmax (group 1, 4.0 ≤ Vmax <4.5 m/s, N=550; group 2, 4.5 ≤ Vmax <5 m/s, N=279; and group 3, Vmax ≥5 m/s, N=246). Cumulative 5‐year incidence of AS‐related events (aortic valve–related death or heart failure hospitalization) was incrementally higher with increasing Vmax (entire population; 38.0%, 49.4%, and 62.8%, P<0.001; symptomatic patients; 55.7%, 60.9%, and 72.2%, P=0.008; and asymptomatic patients; 29.4%, 38.9%, and 47.7%, P=0.005). After adjusting for confounders, the excess risk of group 2 and group 3 relative to group 1 for AS‐related events remained significant (hazard ratio, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.07–1.81; P=0.02, and hazard ratio, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.17–2.00; P=0.002, respectively). The effect size of group 3 relative to group 1 for AS‐related events in asymptomatic patients (N=479) was similar to that in symptomatic patients (N=596; hazard ratio, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.01–2.52; P=0.047, and hazard ratio, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.16–2.40, P=0.008, respectively), and there was no significant overall interaction between the symptomatic status and the effect of the Vmax categories on AS‐related events (interaction, P=0.88).

Conclusions

In conservatively managed severe AS patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, increasing Vmax was associated with incrementally higher risk for AS‐related events. However, the cumulative 5‐year incidence of the AS‐related events remained very high even in asymptomatic patients with less greater Vmax.

Keywords: aortic stenosis, clinical outcomes, peak aortic jet velocity

Subject Categories: Valvular Heart Disease

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

The cumulative 5‐year incidence of the aortic stenosis (AS)‐related events remained very high in asymptomatic patients with less greater Vmax, and increasing peak aortic jet velocity was associated with incrementally higher risk for AS‐related events in conservatively managed severe AS patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The initial aortic valve replacement strategy would be a viable option in asymptomatic patients with severe AS with peak aortic jet velocity 4.0 to 5.0 m/s, although definitive conclusions cannot be drawn until the completion of the ongoing trial comparing initial aortic valve replacement strategy with conservative strategy in patients with asymptomatic severe AS.

Introduction

In the current American and European guidelines for the management of severe aortic stenosis (AS), the presence of AS‐related symptoms is the only 1 class 1 recommendation for aortic valve replacement (AVR) surgery.1, 2 However, many patients with severe AS who could potentially be benefited from AVR may not complain any symptoms because of their sedentary life style. Furthermore, it is often difficult to distinguish the non‐specific symptoms such as fatigue and dyspnea on exertion from the true AS‐related symptoms. Several previous observational studies including our recent report have suggested better long‐term clinical outcomes with initial AVR strategy as compared with conservative strategy in asymptomatic patients with severe AS.3, 4, 5 Therefore, it is increasingly important to identify some additional objective parameters accurately predicting higher‐risk patients with severe AS other than AS‐related symptoms. Myocardial fibrosis detected by magnetic resonance imaging and novel biomarkers for fibrosis or myocyte stress such as growth differentiation factor 15 or soluble ST2 have emerged as promising predictors of outcomes in patients with severe AS.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 However, the diagnostic tests used in the decision making for AVR should be readily and repeatedly available in daily clinical practice. Therefore, among asymptomatic patients with severe AS, the current guidelines recommend AVR as the class 2a indication in patients with very severe AS (peak aortic jet velocity [Vmax] ≥5.0 m/s or mean aortic pressure gradient ≥60 mm Hg), or left ventricular dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] <50%) as evaluated by echocardiography.1, 2 However, there are limited data regarding risk stratification based on Vmax in patients with severe AS, although Vmax as assessed by Doppler echocardiography is considered to be a major predictor of adverse events in patients with moderate or severe AS, leading to the definition of severe AS as Vmax ≥4.0 m/s or mean aortic pressure gradient ≥40 mm Hg.11, 12, 13 Previous single‐center studies have reported that asymptomatic severe AS patients with Vmax ≥5.0 m/s are at higher risk for adverse events,4, 14 whereas other studies reported that patients with Vmax ≥4.5 m/s are at higher risk for adverse events.5, 15 The appropriate cut‐off value for Vmax predicting adverse outcomes has not been yet established in severe AS patients with Vmax ≥4.0 m/s. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the prognostic impact of Vmax in conservatively managed severe AS patients with preserved LVEF using data from a large Japanese multicenter registry of patients with severe AS.

Methods

Study Population

The CURRENT AS (Contemporary Outcomes After Surgery and Medical Treatment in Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis) registry is a retrospective, multicenter registry enrolling consecutive patients with severe AS who were treated at 27 centers in Japan between January 2003 and December 2011. Inclusion periods of the consecutive patients in each center were different according to the accessibility for the hospital chart in each center. The institutional review boards at all 27 participating centers (see Appendix) approved the protocol. Written informed consent from each patient was waived in this retrospective study, because we used clinical information obtained in the routine clinical practice, and no patients refused to participate in the study when contacted for follow‐up.

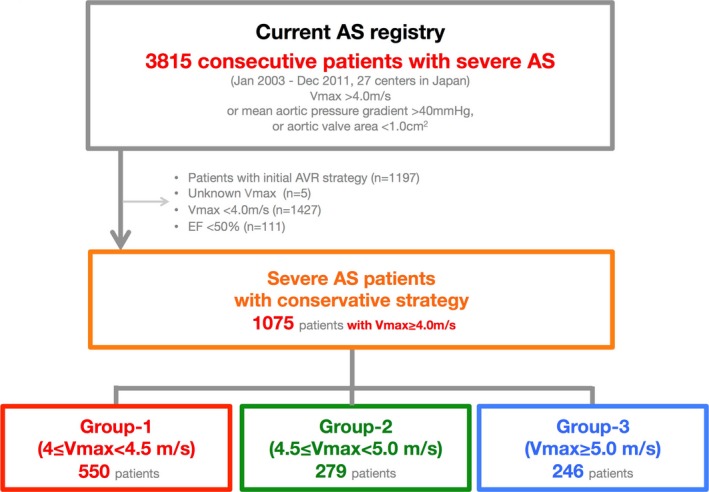

The design and patient enrollment of the CURRENT AS registry have been described previously.3 Among the 3815 patients enrolled in the registry who met the definition of severe AS (Vmax >4.0 m/s, mean aortic pressure gradient >40 mm Hg, or aortic valve area <1.0 cm2) for the first time during the study period, we excluded 1197 patients in whom aortic valve replacement (AVR) was selected as the initial treatment strategy after the index echocardiography, 5 patients whose Vmax values were unknown, 1427 patients whose Vmax values were <4.0 m/s, and 111 patients whose left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was <50%. Therefore, the current study population consisted of 1075 patients with severe AS with Vmax ≥4.0 m/s and LVEF ≥50% who were managed conservatively after the index echocardiography (Figure 1). The study patients were subdivided into 3 groups based on the Vmax values: group 1 (4.0 ≤ Vmax <4.5 m/s: N=550); group 2 (4.5 ≤ Vmax <5 m/s: N=279); and group 3 (Vmax ≥5 m/s: N=246; Figure 1). We compared the baseline characteristics and 5‐year clinical outcomes among the 3 groups.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. Treatment strategies (initial AVR or conservative) were selected shortly after the index echocardiography. AS indicates aortic stenosis; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CURRENT AS, Contemporary Outcomes After Surgery and Medical Treatment in Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis; EF, ejection fraction; Vmax, peak aortic jet velocity.

Data Collection and Definitions

The collection of the baseline clinical information was conducted through hospital chart and database reviews. Angina, syncope, and heart failure (HF) symptoms including dyspnea were regarded as AS‐related symptoms. All patients at each participating center underwent comprehensive 2‐dimensional and Doppler echocardiographic evaluations. Vmax and mean aortic pressure gradient were calculated using the simplified Bernoulli equation. Aortic valve area was calculated using the standard continuity equation and normalized to body surface area.16 Left ventricular (LV) mass was measured with the formula recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography, and was indexed to body surface area as follows: LV mass=0.8×1.04[(LVDd+LVPWTd+IVSTd)3−(LVDd)3]+0.6, where LVDd is the LV diastolic diameter, IVSTd is the diastolic interventricular septal wall thickness, and LVPWTd is the diastolic LV posterior wall thickness. According to the American Society of Echocardiography recommendations, LV hypertrophy was defined as an LV mass index >115 g/m2 in male patients and >95 g/m2 in female patients.17

The follow‐up data were mainly collected through a review of hospital charts or through contact with patients, their relatives, and/or the referring physicians asking questions on survival status, symptoms, and subsequent hospitalization.

The primary outcome measure in the present analysis was a composite of aortic valve–related death and HF hospitalization. Cause of death was classified according to the VARC (Valve Academic Research Consortium) definitions and was adjudicated by a clinical event committee (see Appendix).18, 19 Sudden death was defined as unexplained death in previously stable patients. Aortic valve–related death included aortic procedure–related death, sudden death, and death attributed to HF that was possibly related to the aortic valve. HF hospitalization was defined as hospitalization attributed to worsening HF that required intravenous drug therapy. During collection of clinical outcomes, group categorization by Vmax had not been notified to the investigators. Furthermore, a clinical event committee also adjudicated the outcomes in a blind fashion to the group categorization by Vmax.

Statistical Analysis

We present continuous variables as the mean±SD or median with interquartile range and categorical variables as numbers and percentages. We compared continuous variables using 1‐way ANOVA or the Kruskal–Wallis test according to their distributions. We analyzed categorical variables with the chi‐squared test. We used the Kaplan–Meier method to estimate the cumulative incidences of clinical events and assessed intergroup differences with the log‐rank test. The outcomes of group 2 and group 3 were compared with those of group 1 in multivariable Cox proportional hazard models by using dummy variables. Consistent with our previous report, we used the 19 clinically relevant risk‐adjusting variables (age, male, body mass index <22 kg/m2, acute HF, hypertension, current smoking, diabetes mellitus on insulin therapy, past myocardial infarction, past symptomatic stroke, atrial fibrillation or flutter, aortic/peripheral vascular disease, hemodialysis, anemia, liver cirrhosis, malignancy current under treatment, chronic lung disease, LV mass ≥181 g, any combined valvulvar disease, and tricuspid regurgitation pressure gradient ≥40 mm Hg) indicated in Table 1. With the exception of age, continuous risk‐adjusting variables were dichotomized using clinically meaningful reference values or median values. We treated age as a continuous variable in the Cox proportional hazards models. The center was incorporated as the stratification variable. The effects of group 2 and group 3 relative to group 1 on the clinical outcomes were expressed as adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% CIs. We also calculated overall P values of categorized Vmax. We also performed a subgroup analysis based on the presence or absence of the AS‐related symptoms at baseline with formal interaction analysis between the subgroup factor and the effect of the Vmax categories on the primary outcome measure. We conducted a sensitivity analysis in which patients who had undergone AVR or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) during follow‐up period were censored on the day of AVR or TAVI. Furthermore, we performed another sensitivity analysis of isolated severe asymptomatic AS patients, excluding those patients who had other moderate or severe valvular disease. The follow‐up duration was calculated by the median follow‐up duration of patients who were free from all‐cause death. Statistical analyses were conducted by a physician (K.N.) and a statistician (T.M.) with use of JMP (version 10.0.2) or SAS software (version 9.4; both SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). All of the statistical tests were 2‐tailed. We regarded P<0.05 as statistically significant.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Group 1: 4.0 ≤ Vmax <4.5 | Group 2: 4.5 ≤ Vmax <5.0 | Group 3: Vmax ≥5.0 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=550) | (N=279) | (N=246) | ||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, y | 78.5±9.5 | 79.5±9.9 | 81.8±9.6 | <0.001 |

| Age ≥80 ya | 267 (49) | 148 (53) | 171 (70) | <0.001 |

| Malea | 214 (39) | 89 (32) | 62 (25) | <0.001 |

| BMI <22 kg/m2 a | 328 (60) | 194 (70) | 189 (77) | <0.001 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.47±0.19 | 1.42±0.18 | 1.38±0.19 | <0.001 |

| Symptoms possibly related to AS | 186 (34) | 139 (50) | 154 (63) | <0.001 |

| Acute heart failurea | 79 (14) | 53 (19) | 71 (29) | <0.001 |

| Hypertensiona | 385 (70) | 193 (69) | 160 (65) | 0.37 |

| Current smokinga | 37 (6.7) | 13 (4.7) | 12 (4.9) | 0.38 |

| Dyslipidemia | 178 (32) | 75 (27) | 57 (23) | 0.02 |

| On statin therapy | 122 (22) | 61 (22) | 38 (15) | 0.08 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 120 (22) | 45 (16) | 22 (8.9) | <0.001 |

| On insulin therapya | 23 (4.2) | 11 (3.9) | 2 (0.8) | 0.04 |

| Past myocardial infarctiona | 27 (4.9) | 10 (3.6) | 7 (2.9) | 0.35 |

| Past PCI | 58 (11) | 22 (7.9) | 9 (3.7) | 0.005 |

| Past CABG | 18 (3.3) | 8 (2.9) | 3 (1.2) | 0.25 |

| Past open heart surgery | 37 (6.7) | 22 (7.9) | 5 (2.0) | 0.01 |

| Past symptomatic strokea | 70 (13) | 33 (12) | 28 (12) | 0.85 |

| Atrial fibrillation or fluttera | 108 (20) | 50 (18) | 45 (18) | 0.81 |

| Aortic/peripheral vascular diseasea | 33 (6.0) | 11 (3.9) | 10 (4.1) | 0.32 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.70 |

| Hemodialysisa | 52 (9.5) | 25 (9.0) | 15 (6.1) | 0.28 |

| Anemiaa | 298 (54) | 153 (55) | 154 (63) | 0.07 |

| Liver cirrhosis (Child‐Pugh B or C)a | 6 (1.1) | 3 (1.1) | 5 (2.0) | 0.56 |

| Malignancy currently under treatmenta | 20 (3.6) | 19 (6.8) | 11 (4.5) | 0.12 |

| Chronic lung disease (moderate or severe)a | 13 (2.4) | 19 (6.8) | 10 (4.1) | 0.0008 |

| Coronary artery disease | 119 (22) | 48 (17) | 32 (13) | 0.01 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE, % | 8.5 (5.5–14.4) | 10.4 (5.5–16.1) | 11.8 (7.9–17.2) | <0.001 |

| EuroSCORE II, % | 2.6 (1.6–3.9) | 3.1 (1.8–4.8) | 3.6 (2.3–5.2) | <0.001 |

| STS score (PROM), % | 3.6 (2.2–5.9) | 4.4 (2.4–6.8) | 4.3 (2.6–7.7) | 0.003 |

| Etiology of aortic stenosis | 0.79 | |||

| Degenerative | 497 (90) | 247 (89) | 221 (90) | |

| Congenital | 27 (4.9) | 17 (6.1) | 15 (6.1) | |

| Rheumatic | 24 (3.9) | 11 (3.6) | 8 (3.0) | |

| Infective endocarditis | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 3 (0.6) | 3 (1.1) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Echocardiographic variables | ||||

| Vmax, m/s | 4.2±0.1 | 4.7±0.1 | 5.5±0.4 | <0.001 |

| Peak aortic PG, mm Hg | 71±5 | 89±5 | 120±19 | <0.001 |

| Mean aortic PG, mm Hg | 41±5 | 51±6 | 71±14 | <0.001 |

| AVA (equation of continuity), cm2 | 0.77±0.18 | 0.67±0.19 | 0.54±0.16 | <0.001 |

| AVA index, cm2/m2 | 0.53±0.12 | 0.47±0.12 | 0.39±0.10 | <0.001 |

| LV end‐diastolic diameter, mm | 45±7 | 44±6 | 44±7 | 0.18 |

| LV end‐systolic diameter, mm | 28±6 | 28±5 | 28±6 | 0.75 |

| LVEF, % | 68.0±8.2 | 67.4±8.1 | 67.8±8.9 | 0.62 |

| IVST in diastole, mm | 11±2 | 12±2 | 13±2 | <0.001 |

| PWT in diastole, mm | 11±2 | 12±2 | 12±2 | <0.001 |

| LV mass, ga | 182±57 | 189±53 | 205±58 | <0.001 |

| LV hypertrophy | 313 (70) | 175 (80) | 178 (93) | <0.001 |

| Any combined valvular disease (moderate or severe)a | 196 (36) | 122 (44) | 132 (54) | <0.001 |

| Moderate or severe AR | 108 (20) | 68 (24) | 73 (30) | 0.008 |

| Moderate or severe MS | 11 (2.0) | 9 (3.2) | 11 (4.5) | 0.14 |

| Moderate or severe MR | 86 (16) | 49 (18) | 66 (27) | <0.001 |

| Moderate or severe TR | 70 (13) | 44 (16) | 45 (18) | 0.11 |

| TR pressure gradient ≥40 mm Hga | 64 (12) | 53 (19) | 64 (26) | <0.001 |

We present the categorical variables as number (%), and the continuous variables as mean±SD, or median with interquartile range. AR indicates aortic regurgitation; AVA, aortic valve area; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; IVST, interventricular septum thickness; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MR, mitral regurgitation; MS, mitral stenosis; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PG, pressure gradient; PROM, predicted risk of mortality; PWT, posterior wall thickness; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; Vmax, peak aortic jet velocity.

Risk‐adjusting variables selected for the multivariable Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

With increasing Vmax from group 1 to group 3, the patients became older and more often had female sex, smaller body mass index, AS‐related symptoms, and higher surgical risk scores, whereas they less often had dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, chronic lung disease, and coronary artery disease (Table 1). Regarding the echocardiographic variables, patients with higher Vmax more often had greater LV mass values, LV hypertrophy, combined valvular disease, and higher tricuspid regurgitation gradient. LVEF was comparable across the 3 groups (Table 1).

Clinical Outcomes

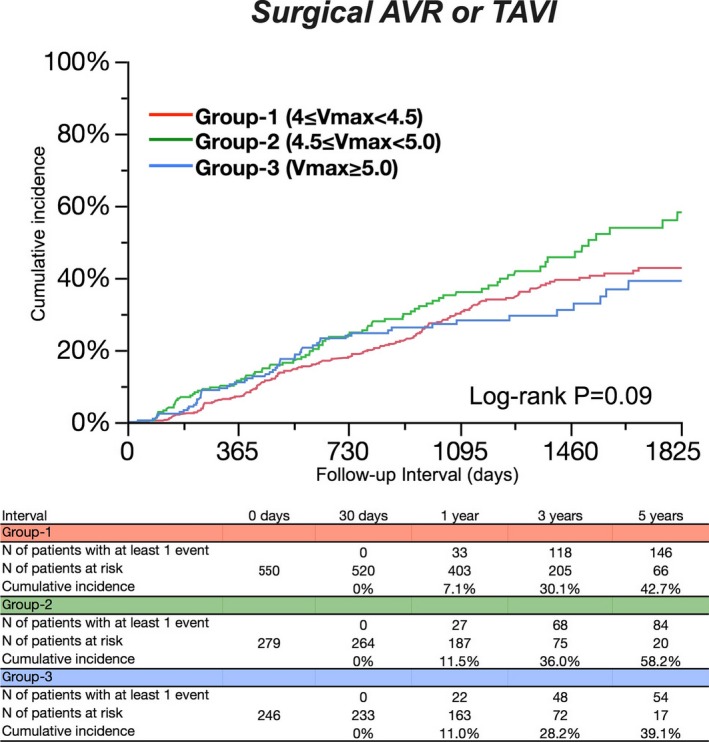

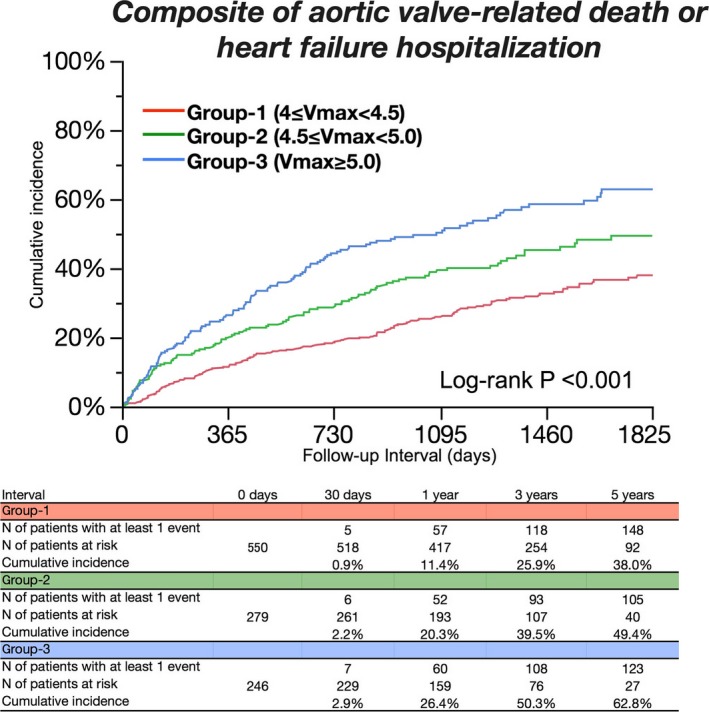

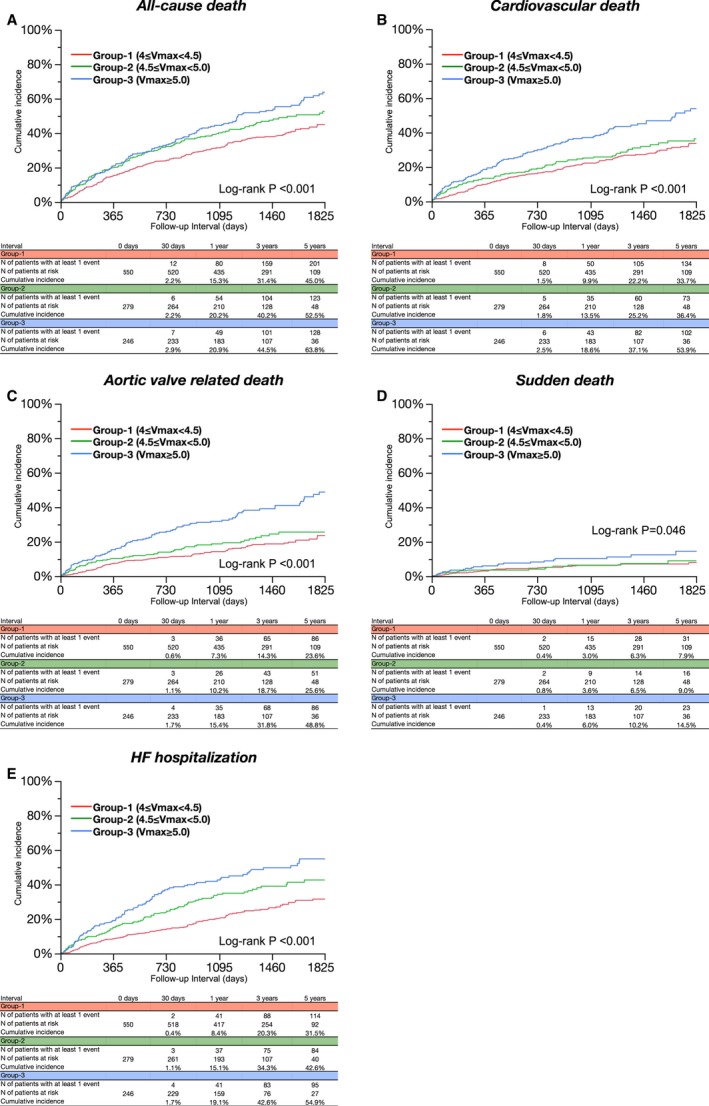

Median follow‐up duration of the surviving patients was 1336 (interquartile range, 966–1817) days. Cumulative 5‐year incidence of surgical AVR or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) was not different among the 3 groups (Figure 2). Cumulative 5‐year incidence of the primary outcome measure (aortic valve–related death or HF hospitalization) was incrementally higher with increasing Vmax from group 1 to group 3 (38.0%, 49.4%, and 62.8%; P<0.001), although the event rate even in group 1 remained very high (Figure 3; Table 2). After adjusting for potential confounders, the excess risk of group 2 and group 3 relative to group 1 for the primary outcome measure remained significant (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.07–1.81; P=0.02, and HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.17–2.00; P=0.002, respectively; Table 3). Cumulative incidences of the secondary outcome measures, including all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, aortic valve–related death, sudden death, and HF hospitalization, among the 3 groups followed the same trend as that for the primary outcome measure (Table 2; Figure 4). After adjusting for confounders, the excess risks of group 3 relative to group 1 for the individual components of the primary outcome measure (aortic valve–related death and HF hospitalization, respectively) remained significant, whereas the risks of group 3 relative to group 1 for the other secondary outcome measures and the risks of group 2 relative to group 1 for the secondary outcome measures, except for all‐cause death and HF hospitalization, were not significant (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative 5‐year incidence for surgical AVR or TAVI. Kaplan–Meier event curves for surgical AVR or TAVI among the 3 groups according to Vmax values. AVR indicates aortic valve replacement; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; Vmax, peak aortic jet velocity.

Figure 3.

Cumulative 5‐year incidence for the primary outcome measure. Kaplan–Meier event curves for the composite of aortic valve–related death or heart failure hospitalization among the 3 groups according to Vmax values. Vmax indicates peak aortic jet velocity.

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes

| Variables | No. of Patients With Event (Cumulative 5‐Y Incidence) | Unadjusted | P Value | Overall P Value | Adjusted | P Value | Overall P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||||||

| Aortic valve–related death/HF hospitalization | |||||||||

| Group 1 (4.0 ≤ Vmax <4.5) | 162 (38.0%) | 1 (reference) | <0.001 | 1 (reference) | 0.004 | ||||

| Group 2 (4.5 ≤ Vmax <5.0) | 113 (49.4%) | 1.52 | 1.19 to 1.93 | <0.001 | 1.39 | 1.07 to 1.81 | 0.02 | ||

| Group 3 (Vmax ≥5.0) | 126 (62.8%) | 2.16 | 1.71 to 2.72 | <0.001 | 1.53 | 1.17 to 2.00 | 0.002 | ||

| All‐cause death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 226 (45.0%) | 1 (reference) | <0.001 | 1 (reference) | 0.11 | ||||

| Group 2 | 135 (52.5%) | 1.27 | 1.02 to 1.57 | 0.03 | 1.29 | 1.02 to 1.64 | 0.04 | ||

| Group 3 | 138 (63.8%) | 1.53 | 1.24 to 1.89 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 0.89 to 1.43 | 0.33 | ||

| Cardiovascular death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 152 (33.7%) | 1 (reference) | <0.001 | 1 (reference) | 0.23 | ||||

| Group 2 | 82 (36.4%) | 1.14 | 0.87 to 1.49 | 0.33 | 1.17 | 0.87 to 1.57 | 0.31 | ||

| Group 3 | 106 (53.9%) | 1.75 | 1.36 to 2.24 | <0.001 | 1.27 | 0.96 to 1.68 | 0.10 | ||

| Aortic valve–related death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 98 (23.6%) | 1 (reference) | <0.001 | 1 (reference) | 0.04 | ||||

| Group 2 | 58 (25.6%) | 1.25 | 0.90 to 1.73 | 0.18 | 1.26 | 0.88 to 1.81 | 0.21 | ||

| Group 3 | 90 (48.8%) | 2.30 | 1.73 to 3.07 | <0.001 | 1.54 | 1.11 to 2.14 | 0.01 | ||

| Sudden death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 32 (7.9%) | 1 (reference) | 0.051 | N/A | |||||

| Group 2 | 20 (9.0%) | 1.30 | 0.73 to 2.25 | 0.36 | N/A | ||||

| Group 3 | 25 (14.5%) | 1.91 | 1.13 to 3.23 | 0.02 | N/A | ||||

| HF hospitalization | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 128 (31.5%) | 1 (reference) | <0.001 | 1 (reference) | 0.03 | ||||

| Group 2 | 89 (42.6%) | 1.52 | 1.16 to 1.99 | 0.003 | 1.37 | 1.01 to 1.85 | 0.04 | ||

| Group 3 | 96 (54.6%) | 2.11 | 1.61 to 2.74 | <0.001 | 1.44 | 1.06 to 1.97 | 0.02 | ||

Number of patients with event was counted through the entire follow‐up period, whereas the cumulative incidence was truncated at 5 years. Aortic valve–related death included aortic procedure–related death, sudden death, and death attributed to heart failure. HF hospitalization was defined as hospitalization attributed to worsening HF requiring intravenous drug therapy. HF indicates heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; N, number; N/A, not assessed; Vmax, peak aortic jet velocity.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Patients

| Symptomatic Patients | P Value | Asymptomatic Patients | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: 4.0 ≤ Vmax <4.5 | Group 2: 4.5 ≤ Vmax <5.0 | Group 3: Vmax ≥5.0 | Group 1: 4.0 ≤ Vmax <4.5 | Group 2: 4.5 ≤ Vmax <5.0 | Group 3: Vmax ≥5.0 | |||

| (N=186) | (N=139) | (N=154) | (N=364) | (N=140) | (N=92) | |||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||||

| Age, y | 81.1±8.9 | 82.6±9.1 | 84.3±7.4 | 0.003 | 77.2±0.5 | 76.4±0.8 | 77.6±1.0 | 0.62 |

| Age ≥80 ya | 109 (59) | 93 (67) | 126 (82) | <0.001 | 158 (43) | 55 (39) | 45 (49) | 0.35 |

| Malea | 61 (33) | 28 (20) | 36 (23) | 0.02 | 153 (42) | 61 (44) | 26 (28) | 0.04 |

| BMI <22 kg/m2 a | 121 (65) | 107 (77) | 124 (81) | 0.003 | 207 (57) | 87 (62) | 65 (71) | 0.047 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.44±0.19 | 1.36±0.17 | 1.33±0.18 | <0.001 | 1.48±0.19 | 1.48±0.18 | 1.46±0.18 | 0.52 |

| Acute heart failurea | 79 (42) | 53 (38) | 71 (46) | 0.39 | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Hypertensiona | 133 (72) | 104 (75) | 106 (69) | 0.52 | 252 (69) | 89 (64) | 54 (59) | 0.12 |

| Current smokinga | 8 (4.3) | 7 (5.0) | 6 (3.9) | 0.89 | 29 (8.0) | 6 (4.3) | 6 (6.5) | 0.34 |

| Dyslipidemia | 53 (28) | 34 (24) | 44 (29) | 0.66 | 125 (34) | 41 (29) | 13 (14) | <0.001 |

| On statin therapy | 35 (19) | 28 (20) | 30 (19) | 0.96 | 87 (24) | 33 (24) | 8 (8.7) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 36 (19) | 21 (15) | 14 (9.1) | 0.03 | 84 (23) | 24 (17) | 8 (8.7) | 0.006 |

| On insulin therapya | 4 (2.2) | 4 (2.9) | 1 (0.7) | 0.35 | 19 (5.2) | 7 (5.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0.22 |

| Past myocardial infarctiona | 10 (5.4) | 4 (2.9) | 4 (2.6) | 0.33 | 17 (4.7) | 6 (4.3) | 3 (3.3) | 0.84 |

| Past PCI | 17 (9.1) | 6 (4.3) | 5 (3.3) | 0.05 | 41 (11) | 16 (11) | 4 (4.4) | 0.13 |

| Past CABG | 9 (4.8) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (1.3) | 0.17 | 9 (2.5) | 4 (2.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0.66 |

| Past open heart surgery | 19 (10) | 10 (7.2) | 3 (2.0) | 0.01 | 18 (5.0) | 12 (8.6) | 2 (2.2) | 0.09 |

| Past symptomatic strokea | 25 (13) | 13 (9.4) | 15 (9.7) | 0.42 | 45 (12) | 20 (14) | 13 (14) | 0.81 |

| Atrial fibrillation or fluttera | 44 (24) | 30 (22) | 38 (25) | 0.82 | 64 (18) | 20 (14) | 7 (7.6) | 0.06 |

| Aortic/peripheral vascular diseasea | 10 (5.4) | 2 (1.4) | 5 (3.3) | 0.16 | 23 (6.3) | 9 (6.4) | 5 (5.4) | 0.94 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.7–1.5) | 0.9 (0.7–1.4) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.97 | 0.8 (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.15 |

| Hemodialysisa | 14 (7.5) | 11 (7.9) | 6 (3.9) | 0.29 | 38 (10) | 14 (10) | 9 (9.8) | 0.98 |

| Anemiaa | 118 (63) | 90 (65) | 109 (71) | 0.33 | 180 (49) | 63 (45) | 45 (49) | 0.66 |

| Liver cirrhosis (Child‐Pugh B or C)a | 4 (2.2) | 3 (2.2) | 5 (3.3) | 0.77 | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.53 |

| Malignancy currently under treatmenta | 5 (2.7) | 8 (5.8) | 4 (2.6) | 0.25 | 15 (4.1) | 11 (7.9) | 7 (7.6) | 0.17 |

| Chronic lung disease (moderate or severe)a | 6 (3.2) | 10 (7.2) | 9 (5.8) | 0.26 | 7 (1.9) | 9 (6.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0.01 |

| Coronary artery disease | 47 (25) | 22 (16) | 19 (12) | 0.006 | 72 (20) | 26 (19) | 13 (14) | 0.46 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE, % | 11.8 (7.0–19.2) | 12.5 (8.4–18.0) | 13.7 (10.1–21.7) | 0.02 | 7.9 (5.1–12.1) | 7.2 (4.8–13.3) | 8.7 (5.1–13.3) | 0.73 |

| EuroSCORE II, % | 3.8 (2.4–6.0) | 4.0 (2.7–5.8) | 4.2 (3.1–6.7) | 0.045 | 2.2 (1.4–3.2) | 2.3 (1.3–3.7) | 2.5 (1.4–3.5) | 0.68 |

| STS score (PROM), % | 5.1 (2.8–8.4) | 5.4 (3.6–9.2) | 5.7 (3.4–9.7) | 0.20 | 3.2 (2.0–5.0) | 3.1 (1.8–5.1) | 3.3 (1.8–4.3) | 0.75 |

| Etiology of aortic stenosis | 0.16 | 0.28 | ||||||

| Degenerative | 172 (92) | 131 (94) | 143 (93) | 325 (89) | 116 (83) | 78 (85) | ||

| Congenital | 4 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | 7 (4.6) | 23 (6.3) | 16 (11) | 8 (8.7) | ||

| Rheumatic | 10 (5.4) | 7 (5.0) | 3 (2.0) | 13 (3.6) | 4 (2.9) | 5 (5.4) | ||

| Infective endocarditis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Echocardiographic variables | ||||||||

| Vmax, m/s | 4.2±0.1 | 4.7±0.1 | 5.5±0.4 | <0.001 | 4.2±0.1 | 4.7±0.1 | 5.3±0.3 | <0.001 |

| Peak aortic PG, mm Hg | 71±5 | 88±5 | 124±21 | <0.001 | 71±5 | 89±6 | 115±13 | <0.001 |

| Mean aortic PG, mm Hg | 41±5 | 51±7 | 74±16 | <0.001 | 41±5 | 52±6 | 67±10 | <0.001 |

| AVA (equation of continuity), cm2 | 0.73±0.19 | 0.63±0.17 | 0.50±0.14 | <0.001 | 0.79±0.18 | 0.70±0.20 | 0.61±0.16 | <0.001 |

| AVA index, cm2/m2 | 0.51±0.12 | 0.46±0.11 | 0.38±0.10 | <0.001 | 0.54±0.11 | 0.48±0.12 | 0.42±0.11 | <0.001 |

| LV end‐diastolic diameter, mm | 46±7 | 44±6 | 44±6 | 0.06 | 45±6 | 45±6 | 44±7 | 0.88 |

| LV end‐systolic diameter, mm | 29±5 | 28±5 | 28±6 | 0.04 | 27±6 | 28±5 | 27±5 | 0.30 |

| LVEF, % | 65.7±8.6 | 67.0±9.2 | 66.5±9.1 | 0.38 | 69.2±7.8 | 67.8±6.9 | 69.9±8.1 | 0.08 |

| IVST in diastole, mm | 12±2 | 12±2 | 13±2 | <0.001 | 11±2 | 12±2 | 13±2 | <0.001 |

| PWT in diastole, mm | 11±2 | 12±2 | 12±2 | <0.001 | 11±2 | 12±2 | 12±2 | <0.001 |

| LV mass, ga | 190±61 | 185±49 | 208±57 | 0.002 | 178±55 | 193±56 | 201±58 | <0.001 |

| LV hypertrophy | 110 (78) | 86 (84) | 118 (97) | <0.001 | 203 (66) | 89 (77) | 60 (86) | <0.001 |

| Any combined valvular disease (moderate or severe)a | 86 (46) | 75 (54) | 99 (64) | 0.004 | 110 (30) | 47 (34) | 33 (36) | 0.52 |

| Moderate or severe AR | 44 (24) | 38 (27) | 50 (32) | 0.19 | 64 (18) | 30 (21) | 23 (25) | 0.23 |

| Moderate or severe MS | 4 (2.2) | 8 (5.8) | 7 (4.6) | 0.23 | 7 (1.9) | 1 (0.7) | 4 (4.4) | 0.15 |

| Moderate or severe MR | 51 (27) | 37 (27) | 58 (38) | 0.06 | 35 (9.6) | 12 (8.6) | 8 (8.7) | 0.92 |

| Moderate or severe TR | 37 (19) | 30 (22) | 36 (23) | 0.74 | 33 (9.1) | 14 (10) | 9 (9.8) | 0.94 |

| TR pressure gradient ≥40 mm Hga | 34 (18) | 38 (27) | 54 (35) | 0.002 | 30 (8.2) | 15 (11) | 10 (11) | 0.58 |

We presented the categorical variables as number (%), and the continuous variables as mean±SD, or median with interquartile range. AR indicates aortic regurgitation; AVA, aortic valve area; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; IVST, interventricular septum thickness; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MR, mitral regurgitation; MS, mitral stenosis; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PG, pressure gradient; PROM, predicted risk of mortality; PWT, posterior wall thickness; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; Vmax, peak aortic jet velocity.

Risk‐adjusting variables selected for the multivariable Cox proportional hazards models.

Figure 4.

Cumulative 5‐year incidence for the secondary outcome measures. Kaplan–Meier event curves for (A) all‐cause death, (B) cardiovascular death, (C) aortic valve‐related death, (D) sudden death, and (E) HF hospitalization among the 3 groups according to Vmax values. HF indicates heart failure; Vmax, peak aortic jet velocity.

Subgroup Analysis Based on the Presence or Absence of AS‐Related Symptoms

There were 479 patients with and 596 patients without AS‐related symptoms at baseline. In the subgroup of symptomatic patients, the differences in baseline characteristics among the 3 groups categorized by the Vmax values were generally consistent with those in the entire study population (Table 3). In the subgroup of asymptomatic patients, baseline characteristics were not so much different among the 3 groups categorized by the Vmax values, except for the higher prevalence of women, and smaller body mass index, as well as the lower prevalence of dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and chronic lung disease with increasing Vmax. Age and surgical risk scores in asymptomatic patients were not significantly different among the 3 groups (Table 3). In both subgroups with and without symptoms at baseline, cumulative 5‐year incidence of the primary outcome measure was incrementally higher with increasing Vmax (Figure 5; Tables 4 and 5). After adjusting for confounders, the higher risk of group 3 relative to group 1 for the primary outcome measure remained significant, whereas the excess risk of group 2 relative to group 1 for the primary outcome measure was no longer significant in both subgroups (Figure 6; Tables 4 and 5). The effect size of group 3 relative to group 1 for the primary outcome measure in asymptomatic patients was similar to that in symptomatic patients, and there was also no significant overall interaction between the symptomatic status at baseline and the effect of the Vmax categories on the primary outcome measure (interaction, P=0.88).

Figure 5.

Cumulative 5‐year incidence for the primary outcome measure in the subgroup analysis. Kaplan–Meier event curves for the composite of aortic valve–related death or heart failure hospitalization among the 3 groups according to Vmax values (A) in symptomatic patients and (B) in asymptomatic patients. AS indicates aortic stenosis; Vmax, peak aortic jet velocity.

Table 4.

Clinical Outcomes in Symptomatic Patients

| Variables | No. of Patients With Event (Cumulative 5‐Y Incidence) | Unadjusted | P Value | Overall P Value | Adjusted | P Value | Overall P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||||||

| Aortic valve–related death/HF hospitalization | |||||||||

| Group 1 (4.0 ≤ Vmax <4.5) | 80 (55.7%) | 1 (reference) | 0.009 | 1 (reference) | 0.02 | ||||

| Group 2 (4.5 ≤ Vmax <5.0) | 68 (60.9%) | 1.52 | 1.19 to 1.93 | <0.001 | 1.31 | 0.89 to 1.92 | 0.18 | ||

| Group 3 (Vmax ≥5.0) | 91 (72.2%) | 2.16 | 1.71 to 2.72 | <0.001 | 1.67 | 1.16 to 2.40 | 0.006 | ||

| All‐cause death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 102 (55.8%) | 1 (reference) | 0.32 | 1 (reference) | 0.33 | ||||

| Group 2 | 77 (60.3%) | 1.1 | 0.82 to 1.48 | 0.53 | 1.31 | 0.92 to 1.86 | 0.14 | ||

| Group 3 | 96 (69.3%) | 1.24 | 0.94 to 1.64 | 0.13 | 1.17 | 0.84 to 1.63 | 0.37 | ||

| Cardiovascular death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 75 (45.6%) | 1 (reference) | 0.06 | 1 (reference) | 0.71 | ||||

| Group 2 | 46 (40.8%) | 0.88 | 0.61 to 1.27 | 0.50 | 1.02 | 0.65 to 1.54 | 0.99 | ||

| Group 3 | 76 (58.4%) | 1.33 | 0.97 to 1.83 | 0.08 | 1.16 | 0.79 to 1.70 | 0.46 | ||

| Aortic valve–related death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 51 (34.0%) | 1 (reference) | 0.002 | 1 (reference) | 0.16 | ||||

| Group 2 | 33 (28.4%) | 0.93 | 0.60 to 1.44 | 0.76 | 1.13 | 0.68 to 1.87 | 0.65 | ||

| Group 3 | 67 (54.9%) | 1.73 | 1.20 to 2.49 | 0.003 | 1.51 | 0.98 to 2.34 | 0.06 | ||

| Sudden death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 14 (10.3%) | 1 (reference) | 0.48 | N/A | |||||

| Group 2 | 12 (10.8%) | 1.21 | 0.55 to 2.62 | 0.63 | N/A | ||||

| Group 3 | 17 (17.9%) | 1.54 | 0.76 to 3.19 | 0.23 | N/A | ||||

| HF hospitalization | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 65 (50.4%) | 1 (reference) | 0.051 | 1 (reference) | 0.12 | ||||

| Group 2 | 56 (56.8%) | 1.31 | 0.91 to 1.87 | 0.14 | 1.36 | 0.89 to 2.10 | 0.16 | ||

| Group 3 | 69 (64.4%) | 1.52 | 1.08 to 2.14 | 0.02 | 1.52 | 1.01 to 2.30 | 0.045 | ||

Number of patients with event was counted through the entire follow‐up period, whereas the cumulative incidence was truncated at 5 years. Aortic valve–related death included aortic procedure‐related death, sudden death, and death attributed to HF. HF hospitalization was defined as hospitalization attributed to worsening HF requiring intravenous drug therapy. HF indicates heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; N, number; N/A, not assessed; Vmax, peak aortic jet velocity.

Table 5.

Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic Patients

| Variables | No. of Patients With Event (Cumulative 5‐Y Incidence) | Unadjusted | P Value | Overall P Value | Adjusted | P Value | Overall P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||||||

| Aortic valve–related death/HF hospitalization | |||||||||

| Group 1 (4.0 ≤ Vmax <4.5) | 82 (29.4%) | 1 (reference) | 0.006 | 1 (reference) | 0.11 | ||||

| Group 2 (4.5 ≤ Vmax <5.0) | 45 (38.9%) | 1.42 | 0.98 to 2.03 | 0.06 | 1.31 | 0.86 to 1.99 | 0.20 | ||

| Group 3 (Vmax ≥5.0) | 35 (47.7%) | 1.86 | 1.23 to 2.73 | 0.004 | 1.59 | 1.01 to 2.52 | 0.047 | ||

| All‐cause death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 124 (39.4%) | 1 (reference) | 0.17 | 1 (reference) | 0.24 | ||||

| Group 2 | 58 (45.4%) | 1.21 | 0.88 to 1.65 | 0.23 | 1.34 | 0.94 to 1.92 | 0.11 | ||

| Group 3 | 42 (54.0%) | 1.36 | 0.95 to 1.91 | 0.10 | 1.23 | 0.83 to 1.82 | 0.31 | ||

| Cardiovascular death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 77 (27.5%) | 1 (reference) | 0.11 | 1 (reference) | 0.31 | ||||

| Group 2 | 36 (32.0%) | 1.21 | 0.81 to 1.78 | 0.35 | 1.27 | 0.79 to 2.03 | 0.33 | ||

| Group 3 | 30 (45.5%) | 1.56 | 1.01 to 2.36 | 0.045 | 1.43 | 0.88 to 2.33 | 0.15 | ||

| Aortic valve–related death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 47 (18.4%) | 1 (reference) | 0.03 | 1 (reference) | 0.18 | ||||

| Group 2 | 25 (22.3%) | 1.38 | 0.84 to 2.22 | 0.20 | 1.46 | 0.81 to 2.62 | 0.21 | ||

| Group 3 | 23 (38.1%) | 1.95 | 1.16 to 3.18 | 0.001 | 1.69 | 0.94 to 3.07 | 0.08 | ||

| Sudden death | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 18 (6.9%) | 1 (reference) | 0.42 | N/A | |||||

| Group 2 | 8 (7.5%) | 1.15 | 0.47 to 2.56 | 0.74 | N/A | ||||

| Group 3 | 8 (10.2%) | 1.76 | 0.72 to 3.91 | 0.20 | N/A | ||||

| HF hospitalization | |||||||||

| Group 1 | 63 (22.8%) | 1 (reference) | 0.02 | 1 (reference) | 0.18 | ||||

| Group 2 | 33 (30.3%) | 1.35 | 0.87 to 2.04 | 0.17 | 1.19 | 0.73 to 1.94 | 0.50 | ||

| Group 3 | 27 (41.0%) | 1.87 | 1.17 to 2.91 | 0.009 | 1.65 | 0.97 to 2.83 | 0.07 | ||

Number of patients with event was counted through the entire follow‐up period, whereas the cumulative incidence was truncated at 5 years. Aortic valve–related death included aortic procedure‐related death, sudden death, and death attributed to HF. HF hospitalization was defined as hospitalization attributed to worsening heart failure requiring intravenous drug therapy. HF indicates heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; N, number; N/A, not assessed; Vmax, peak aortic jet velocity.

Figure 6.

Unadjusted and adjusted effects of increasing Vmax on the primary outcome measure in the entire study population and in the subgroups based on symptomatic status at baseline. Unadjusted and adjusted effects of group 2 (4.5 ≤ Vmax <5.0 m/s) and group 3 (Vmax ≥5.0 m/s) relative to group 1 (reference: 4.0 ≤ Vmax <4.5 m/s) on the composite of aortic valve–related death or heart failure hospitalization were analyzed in the entire study population as well as in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. There was no significant overall interaction between symptomatic status and effect of Vmax categories (interaction, P=0.88). AS indicates aortic stenosis; HR, hazard ratio; N, number; Vmax, peak aortic jet velocity.

Sensitivity Analysis

When patients who had undergone AVR or TAVI during follow‐up period were censored on the day of AVR or TAVI, an incrementally higher risk for the composite of aortic valve–related death or HF hospitalization with increasing Vmax was similarly observed as in the main analysis (adjusted HR for group 2 relative to group 1, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.03–1.82, P=0.03, and adjusted HR for group 3 relative to group 1, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.28–2.24; P<0.001). Furthermore, when this analysis was restricted to isolated severe asymptomatic AS patients, the cumulative 5‐year incidence of the primary outcome measure was incrementally higher with increasing Vmax (27.8%, 43.2%, and 48.5%; log‐rank, P=0.02). After adjusting for possible confounders, the excess risk of group 2 and group 3 relative to group 1 for the primary outcome measure was no longer significant in the isolated severe asymptomatic severe AS patients (adjusted HR for group 2 relative to group 1, 1.27; 95% CI, 0.75–2.17; P=0.38, and adjusted HR for group 3 relative to group 1, 1.32; 95% CI, 0.70–2.48; P=0.40). However, the magnitude of the effect of increasing Vmax for the primary outcome measure was not so much different from that in the entire study population.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study were the following: (1) In conservatively managed severe AS (Vmax ≥4.0 m/s) patients with preserved LVEF, increasing Vmax (4.5–5.0 m/s and ≥5.0 m/s) was associated with incrementally higher risk for the primary composite outcome measure of aortic valve–related death or HF hospitalization; (2) however, the cumulative 5‐year incidence of the AS‐related serious adverse events remained very high even in asymptomatic patients with Vmax 4.0 to 4.5 m/s.

There are several previous studies evaluating the relation between Vmax and long‐term clinical outcomes in patients with severe AS (Vmax ≥4.0 or 4.5 m/s).4, 5, 14, 15 Kang et al reported that patients with Vmax ≥5.0 m/s were associated with higher cardiac mortality in 197 asymptomatic patients with very severe AS (Vmax ≥4.5 m/s).4 Kitai et al reported that patients with very severe AS (Vmax ≥5.0 m/s, mean pressure gradient ≥50 mm Hg, or aortic valve area <0.6 cm2) were associated with higher mortality and higher valve‐related event (cardiac death/HF hospitalization) among 108 conservatively managed patients with severe AS (Vmax ≥4.0 m/s, mean PG ≥40 mm Hg, or aortic valve area <1.0 cm2).14 Pellikka et al reported that patients with very severe AS (Vmax ≥4.5 m/s) were associated with higher risk for cardiac death or AVR with a relative risk of 4.9 among 143 asymptomatic patients with severe AS (Vmax ≥4.0 m/s),5 whereas the same group of investigators later reported that patients with very severe AS (Vmax ≥4.5 m/s) were associated with higher risk for cardiac death or AVR with an HR of 1.48 among 622 asymptomatic patients with severe AS (Vmax ≥4.0 m/s).15 All these previous studies were single‐center studies from the high‐quality centers, which might be associated with some limitations in extrapolating the study results into real clinical practice with differences in the quality of echocardiographic examinations, manner of patient follow‐up, and operative mortality rate of AVR across centers. Furthermore, mean age of the patients enrolled in these studies ranged from 63 to 72 years, which would be much younger than the age of patients encountered in the contemporary clinical practice. In the present study evaluating the largest ever number of patients with average age of 80 years from 27 centers, increasing Vmax, particularly Vmax ≥5.0 m/s, was clearly associated with worse long‐term AS‐related outcomes, consistent with previous studies. Notably, the effect size of Vmax ≥5.0 m/s relative to Vmax 4.0 to 4.5 m/s for aortic valve–related death or HF hospitalization in asymptomatic patients was similar to that in symptomatic patients, supporting the guidelines recommendation of AVR in asymptomatic patients with very severe AS (Vmax ≥5.0 m/s).1, 2 Otto et al reported that Vmax value was an independent predictor of death or AVR among 123 asymptomatic moderate‐to‐severe AS patients (Vmax ≥2.5 m/s).20 Also, Gerdts et al reported that an association between increasing Vmax value and incrementally higher risk for cardiovascular events in mild‐to‐moderate asymptomatic AS patients (Vmax ≥2.5 m/s).21 Furthermore, Rosenhek et al reported that patients with Vmax ≥5.5 m/s were associated with a higher risk for cardiac death or indication for AVR among 116 asymptomatic isolated very severe AS patients (Vmax ≥5.0 m/s).22 However, it should be noted that the event rate for aortic valve–related death or HF hospitalization in this study remained very high even in asymptomatic patients with Vmax 4.0 to 4.5 m/s. Too much emphasis on the Vmax values in the decision making for AVR might expose the patients to unacceptably high event risk within a few years. Based on the results from several observational studies suggesting better long‐term clinical outcomes with initial AVR strategy as compared with conservative strategy in asymptomatic patients with severe AS,3, 4, 5 the initial AVR strategy would be a viable option in asymptomatic patients with severe AS with Vmax 4.0 to 5.0 m/s, although the definitive conclusion could not be drawn until the completion of the ongoing trial comparing initial AVR strategy with conservative strategy in patients with asymptomatic severe AS.23

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. First, we should take the measurement error of the echocardiographic Vmax into account in this study and also in the daily clinical practice. Furthermore, the echocardiographic measurement was not performed in a core laboratory, but in each participating center. Therefore, we could not deny the possibility for variations in the echocardiographic measurement of Vmax. However, cardiologists and ultrasonographers in each participating center had enough experience of echocardiography, and the measurements were performed according to the current guidelines.16 Second, patients with greater Vmax were more likely to undergo AVR. Therefore, we should assume the presence of selection bias among the groups categorized by Vmax, because the conservatively managed patients with greater Vmax might include higher proportion of sicker patients unsuitable for AVR. However, we chose the AS‐related outcomes (aortic valve–related death or HF hospitalization) as the primary outcome measure, which would be less likely to be influenced by selection bias than all‐cause death. Third, we did not have data on the place where patients were regularly followed during the study period and whether the patients were included in any follow‐up programs or not. However, in ≈85% of patients, final follow‐up information was obtained from the hospital chart in the study participating center, suggesting that the majority of patients were followed by the cardiologists in the study participating center. Finally, the presence of AS‐related symptoms is a class 1 indication of AVR. Therefore, risk stratification by Vmax in symptomatic patients may not be necessary. However, in the real clinical practice, patients sometimes refuse AVR despite the presence of symptoms. Also, it is sometimes difficult to make unequivocal diagnosis of AS‐related symptoms. Therefore, we did not exclude the symptomatic patients, but rather conducted a stratified analysis based on the presence or absence of symptoms.

Conclusions

In conservatively managed severe AS patients with preserved LVEF, increasing Vmax was associated with incrementally higher risk for the composite of aortic valve–related death or HF hospitalization. However, the cumulative 5‐year incidence of the AS‐related serious adverse events remained very high even in asymptomatic patients with less greater Vmax.

Sources of Funding

The current study was supported by Kyoto University.

Disclosures

None.

CURRENT AS Registry Investigators

Principal Investigators

Takeshi Kimura, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan; Ryuzo Sakata Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan.

List of participating centers and investigators for the CURRENT AS registry

Cardiology

Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine: Takeshi Kimura, Tomohiko Taniguchi, Hiroki Shiomi, Naritatsu Saito, Masao Imai, Junichi Tazaki, Toshiaki Toyota, Hirooki Higami, Tetsuma Kawaji; Department of Cardiology, Kokura Memorial Hospital: Kenji Ando, Shinichi Shirai, Kengo Korai, Takeshi Arita, Shiro Miura, Kyohei Yamaji; Division of Cardiology, Shimada Municipal Hospital: Takeshi Aoyama, Norio Kanamori; Department of Cardiology, Shizuoka City Shizuoka Hospital: Tomoya Onodera, Koichiro Murata; Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital: Yutaka Furukawa, Takeshi Kitai, Kitae Kim; Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kurashiki Central Hospital: Kazushige Kadota, Yuichi Kawase, Keiichiro Iwasaki, Hiroshi Miyawaki, Ayumi Misao, Akimune Kuwayama, Masanobu Ohya, Takenobu Shimada, Hidewo Amano; Department of Cardiology, Tenri Hospital: Yoshihisa Nakagawa, Chisato Izumi, Makoto Miyake, Masashi Amano, Yusuke Takahashi, Yusuke Yoshikawa, Shunsuke Nishimura, Maiko Kuroda; Division of Cardiology, Nara Hospital, Kinki University Faculty of Medicine: Manabu Shirotani, Hirokazu Mitsuoka; Department of Cardiology, Mitsubishi Kyoto Hospital: Shinji Miki, Tetsu Mizoguchi, Masashi Kato, Takafumi Yokomatsu, Akihiro Kushiyama, Hidenori Yaku, Toshimitsu Watanabe; Department of Cardiology, Kinki University Hospital: Shunichi Miyazaki, Yutaka Hirano; Department of Cardiology, Kishiwada City Hospital: Mitsuo Matsuda, Shintaro Matsuda, Sachiko Sugioka; Department of Cardiovascular Center Osaka Red Cross Hospital: Tsukasa Inada, Kazuya Nagao, Naoki Takahashi, Kohei Fukuchi; Department of Cardiology, Koto Memorial Hospital: Tomoyuki Murakami, Hiroshi Mabuchi, Teruki Takeda, Tomoko Sakaguchi, Keiko Maeda, Masayuki Yamaji, Motoyoshi Maenaka, Yutaka Tadano; Department of Cardiology, Shizuoka General Hospital: Hiroki Sakamoto, Yasuyo Takeuchi, Makoto Motooka, Ryusuke Nishikawa; Department of Cardiology, Nishikobe Medical Center: Hiroshi Eizawa, Keiichiro Yamane, Mitsunori Kawato, Minako Kinoshita, Kenji Aida; Department of Cardiology, Japanese Red Cross Wakayama Medical Center: Takashi Tamura, Mamoru Toyofuku, Kousuke Takahashi, Euihong Ko; Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center: Masaharu Akao, Mitsuru Ishii, Nobutoyo Masunaga, Hisashi Ogawa, Moritake Iguchi, Takashi Unoki, Kensuke Takabayashi, Yasuhiro Hamatani, Yugo Yamashita; Cardiovascular Center, The Tazuke Kofukai Medical Research Institute, Kitano Hospital: Moriaki Inoko, Eri Minamino‐Muta, Takao Kato; Department of Cardiology, Hikone Municipal Hospital: Yoshihiro Himura, Tomoyuki Ikeda; Department of Cardiology, Kansai Electric Power Hospital: Katsuhisa Ishii, Akihiro Komasa; Department of Cardiology, Hyogo Prefectural Amagasaki General Medical Center: Yukihito Sato, Kozo Hotta, Shuhei Tsuji; Department of Cardiology, Rakuwakai Otowa Hospital: Yuji Hiraoka, Nobuya Higashitani; Department of Cardiology, Saiseikai Noe Hospital: Ichiro Kouchi, Yoshihiro Kato; Department of Cardiology, Shiga Medical Center for Adults: Shigeru Ikeguchi, Yasutaka Inuzuka, Soji Nishio, Jyunya Seki; Department of Cardiology, Hamamatsu Rosai Hospital: Eiji Shinoda, Miho Yamada, Akira Kawamoto, Chiyo Maeda; Department of Cardiology, Japanese Red Cross Otsu Hospital: Takashi Konishi, Toshikazu Jinnai, Kouji Sogabe, Michiya Tachiiri, Yukiko Matsumura, Chihiro Ota; Department of Cardiology, Hirakata Kohsai Hospital: Shoji Kitaguchi, Yuko Morikami.

Cardiovascular Surgery

Department of Cardiovascular Surgery Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine: Ryuzo Sakata, Kenji Minakata, Kenji Minatoya; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Kokura Memorial Hospital: Michiya Hanyu; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Shizuoka City Shizuoka Hospital: Fumio Yamazaki; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital: Tadaaki Koyama; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Kurashiki Central Hospital: Tatsuhiko Komiya; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Tenri Hospital: Kazuo Yamanaka; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Nara Hospital, Kinki University Faculty of Medicine: Noboru Nishiwaki; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Mitsubishi Kyoto Hospital: Hiroyuki Nakajima, Motoaki Ohnaka, Hiroaki Osada, Katsuaki Meshii; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Kinki University Hospital: Toshihiko Saga; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Kishiwada City Hospital: Masahiko Onoe, Hitoshi Kitayama; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Osaka Red Cross Hospital: Shogo Nakayama; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Shizuoka General Hospital: Genichi Sakaguchi; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Japanese Red Cross Wakayama Medical Center: Atsushi Iwakura; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center: Kotaro Shiraga; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Cardiovascular Center, The Tazuke Kofukai Medical Research Institute, Kitano Hospital: Koji Ueyama; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Hyogo Prefectural Amagasaki General Medical Center: Keiichi Fujiwara; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Rakuwakai Otowa Hospital: Atsushi Fukumoto; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Shiga Medical Center for Adults: Senri Miwa; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Hamamatsu Rosai Hospital: Junichiro Nishizawa; Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Japanese Red Cross Otsu Hospital: Mitsuru Kitano.

A clinical event committee

Hirotoshi Watanabe, MD (Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine); Kenji Nakatsuma, MD (Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine), Tomoki Sasa, MD (Kishiwada City Hospital).

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005524 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005524.)28739863

References

- 1. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Guyton RA, O'Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM, Thomas JD; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2438–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, Antunes MJ, Baron‐Esquivias G, Baumgartner H, Borger MA, Carrel TP, De Bonis M, Evangelista A, Falk V, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Pierard L, Price S, Schafers H‐J, Schuler G, Stepinska J, Swedberg K, Takkenberg J, Von Oppell UO, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Zembala M, Bax JJ, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, Dean V, Deaton C, Fagard R, Funck‐Brentano C, Hasdai D, Hoes A, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, McDonagh T, Moulin C, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Vahanian A, Windecker S, Popescu BA, Von Segesser L, Badano LP, Bunc M, Claeys MJ, Drinkovic N, Filippatos G, Habib G, Kappetein AP, Kassab R, Lip GYH, Moat N, Nickenig G, Otto CM, Pepper J, Piazza N, Pieper PG, Rosenhek R, Shuka N, Schwammenthal E, Schwitter J, Mas PT, Trindade PT, Walther T. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012): the Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio‐Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2451–2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taniguchi T, Morimoto T, Shiomi H, Ando K, Kanamori N, Murata K, Kitai T, Kawase Y, Izumi C, Miyake M, Mitsuoka H, Kato M, Hirano Y, Matsuda S, Nagao K, Inada T, Murakami T, Takeuchi Y, Yamane K, Toyofuku M, Ishii M, Minamino‐Muta E, Kato T, Inoko M, Ikeda T, Komasa A, Ishii K, Hotta K, Higashitani N, Kato Y, Inuzuka Y, Maeda C, Jinnai T, Morikami Y, Sakata R, Kimura T. Initial surgical versus conservative strategies in patients with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2827–2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kang DH, Park SJ, Rim JH, Yun SC, Kim DH, Song JM, Choo SJ, Park SW, Song JK, Lee JW, Park PW. Early surgery versus conventional treatment in asymptomatic very severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2010;121:1502–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pellikka PA, Nishimura RA, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ. The natural history of adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:1012–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weidemann F, Herrmann S, Stork S, Niemann M, Frantz S, Lange V, Beer M, Gattenlohner S, Voelker W, Ertl G, Strotmann JM. Impact of myocardial fibrosis in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2009;120:577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Azevedo CF, Nigri M, Higuchi ML, Pomerantzeff PM, Spina GS, Sampaio RO, Tarasoutchi F, Grinberg M, Rochitte CE. Prognostic significance of myocardial fibrosis quantification by histopathology and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with severe aortic valve disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:278–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dweck MR, Joshi S, Murigu T, Alpendurada F, Jabbour A, Melina G, Banya W, Gulati A, Roussin I, Raza S, Prasad NA, Wage R, Quarto C, Angeloni E, Refice S, Sheppard M, Cook SA, Kilner PJ, Pennell DJ, Newby DE, Mohiaddin RH, Pepper J, Prasad SK. Midwall fibrosis is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1271–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lancellotti P, Dulgheru R, Magne J, Henri C, Servais L, Bouznad N, Ancion A, Martinez C, Davin L, Le Goff C, Nchimi A, Piérard L, Oury C. Elevated plasma soluble ST2 is associated with heart failure symptoms and outcome in aortic stenosis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lindman BR, Breyley JG, Schilling JD, Vatterott AM, Zajarias A, Maniar HS, Damiano RJ, Moon MR, Lawton JS, Gage BF, Sintek MA, Aquino A, Holley CL, Patel NM, Lawler C, Lasala JM, Novak E. Prognostic utility of novel biomarkers of cardiovascular stress in patients with aortic stenosis undergoing valve replacement. Heart. 2015;101:1382–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lancellotti P, Donal E, Magne J, Moonen M, O'Connor K, Daubert J‐C, Pierard LA. Risk stratification in asymptomatic moderate to severe aortic stenosis: the importance of the valvular, arterial and ventricular interplay. Heart. 2010;96:1364–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Monin J‐L, Lancellotti P, Monchi M, Lim P, Weiss E, Piérard L, Guéret P. Risk score for predicting outcome in patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2009;120:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stewart RAH, Kerr AJ, Whalley GA, Legget ME, Zeng I, Williams MJA, Lainchbury J, Hamer A, Doughty R, Richards MA, White HD. Left ventricular systolic and diastolic function assessed by tissue Doppler imaging and outcome in asymptomatic aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2216–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kitai T, Honda S, Okada Y, Tani T, Kim K, Kaji S, Ehara N, Kinoshita M, Kobori A, Yamamuro A, Kita T, Furukawa Y. Clinical outcomes in non‐surgically managed patients with very severe versus severe aortic stenosis. Heart. 2011;97:2029–2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pellikka PA, Sarano ME, Nishimura RA, Malouf JF, Bailey KR, Scott CG, Barnes ME, Tajik AJ. Outcome of 622 adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis during prolonged follow‐up. Circulation. 2005;111:3290–3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baumgartner H, Hung J, Bermejo J, Chambers JB, Evangelista A, Griffin BP, Iung B, Otto CM, Pellikka PA, Quiñones M. Echocardiographic assessment of valve stenosis: EAE/ASE recommendations for clinical practice. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor‐Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt J‐U. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–39.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, Piazza N, van Mieghem NM, Blackstone EH, Brott TG, Cohen DJ, Cutlip DE, van Es G‐A, Hahn RT, Kirtane AJ, Krucoff MW, Kodali S, Mack MJ, Mehran R, Rodés‐Cabau J, Vranckx P, Webb JG, Windecker S, Serruys PW, Leon MB. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1438–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leon MB, Piazza N, Nikolsky E, Blackstone EH, Cutlip DE, Kappetein AP, Krucoff MW, Mack M, Mehran R, Miller C, Morel M, Petersen J, Popma JJ, Takkenberg JJM, Vahanian A, van Es G‐A, Vranckx P, Webb JG, Windecker S, Serruys PW. Standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:253–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Otto CM, Burwash IG, Legget ME, Munt BI, Fujioka M, Healy NL, Kraft CD, Miyake‐Hull CY, Schwaegler RG. Prospective study of asymptomatic valvular aortic stenosis. Clinical, echocardiographic, and exercise predictors of outcome. Circulation. 1997;95:2262–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gerdts E, Rossebø AB, Pedersen TR, Boman K, Brudi P, Chambers JB, Egstrup K, Gohlke‐Bärwolf C, Holme I, Kesäniemi YA, Malbecq W, Nienaber C, Ray S, Skjærpe T, Wachtell K, Willenheimer R. Impact of baseline severity of aortic valve stenosis on effect of intensive lipid lowering therapy (from the SEAS study). Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1634–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosenhek R, Zilberszac R, Schemper M, Czerny M, Mundigler G, Graf S, Bergler‐Klein J, Grimm M, Gabriel H, Maurer G. Natural history of very severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2010;121:151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Banovic M, Iung B, Bartunek J, Asanin M, Beleslin B, Biocina B, Casselman F, da Costa M, Deja M, Gasparovic H, Kala P, Labrousse L, Loncar Z, Marinkovic J, Nedeljkovic I, Nedeljkovic M, Nemec P, Nikolic SD, Pencina M, Penicka M, Ristic A, Sharif F, Van Camp G, Vanderheyden M, Wojakowski W, Putnik S. Rationale and design of the Aortic Valve replAcemenT versus conservative treatment in Asymptomatic seveRe aortic stenosis (AVATAR trial): a randomized multicenter controlled event‐driven trial. Am Heart J. 2016;174:147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]