Abstract

We report the acute onset of aseptic sinusitis in two patients receiving the immune checkpoint inhibitors, ipilimumab and nivolumab, for treatment of metastatic melanoma. Ipilimumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting CTLA-4, and nivolumab, targeting PD-1, have been associated with numerous immune-related adverse events (IRAE). To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report of aseptic sinusitis as a consequence of immune checkpoint inhibition therapy.

Case Presentations

Case 1

A 35-year-old man with no prior medical history presented after noticing a lump in his right upper neck in July 2015, and subsequently had biopsy-proven stage IV-M1a metastatic melanoma with a primary lesion discovered on his right scalp. Metastasis was limited to cervical lymph nodes, and he was treated with scalp lesion excision and cervical lymphadenectomy in August 2015. He began combination immunotherapy with one dose of ipilimumab 3mg/kg and nivolumab 1mg/kg in October 2015. Two and a half weeks after initial treatment, he developed nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea and was diagnosed with enteritis secondary to immunotherapy. These symptoms improved on prednisone 80 mg twice daily tapered off over four weeks. In early December, he was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation and was electrically cardioverted back to normal sinus rhythm. He also received antibiotics for sterile pyuria, later thought to be urethritis.

On December 14, 2015, he received a second dose of nivolumab. One week later, he developed symptoms of bilateral conjunctivitis and periorbital swelling. On January 1, 2016, he complained of new onset maxillary and frontal sinus pain and pressure without nasal discharge or fever. He received no relief with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and fluconazole. Additionally, he began to have bilateral knee and ankle pain and swelling that persisted despite ibuprofen 800 mg 2–3 times per day. He was started on prednisone 40 mg daily, with improvement of facial swelling and sinus pain and pressure, but had no significant benefit for his joint symptoms. Conjunctivitis also improved, with persistence of dry eyes. When steroids were discontinued, he had increase in wrist and face swelling as well as bilateral temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain. His prednisone was then increased to as high as 160 mg daily.

He presented to rheumatology for initial evaluation in February 2016. Examination was notable for bilateral knee, ankle, and wrist synovitis despite high dose prednisone. Rheumatologic labs, including anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies, rheumatoid factor, HLA-B27 and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), anti-proteinase-3 (PR3) and anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO) were negative. ESR and CRP were elevated at 80 (normal 1–15 mm/h) and 10.2 (normal <0.5 mg/dL), respectively. Prednisone was tapered, and due to lack of response of his inflammatory arthritis to steroids, he started adalimumab 40 mg, intended to be dosed every other week, on March 7, 2016. Within two days of the first dose, he noted improvement of swelling and pain in his joints. At follow-up one week after a single dose of adalimumab, he had significantly improved joint pain and stiffness, but still had persistent swelling in bilateral wrists, knees, and right 3rd metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint. He also had recurrence of nasal congestion, new green nasal discharge and sinus pressure with no fevers, which started just prior to the dose of adalimumab. He received azithromycin for five days, and later levofloxacin for seven days, with no benefit. Adalimumab was held due to concern for infection.

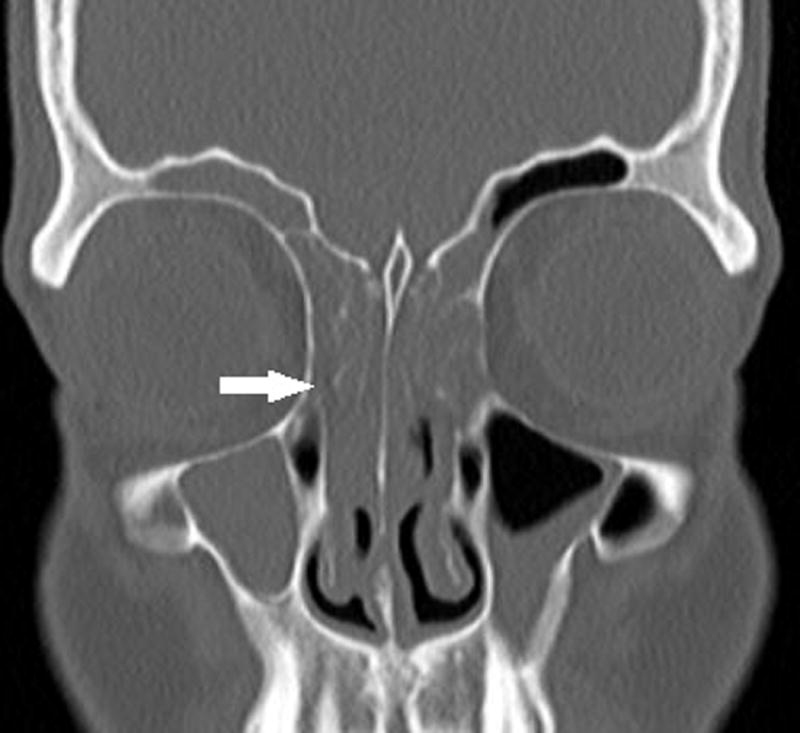

In April, his frontal sinus pain, pressure and discharge had worsened despite these two courses of antibiotics, and severe pan-sinusitis was demonstrated on facial CT sinus (figure 1). Imaging showed no air-fluid levels or suggestion of invasive fungal infection. Otolaryngology evaluated the patient’s sinuses with an intranasal endoscopic exam demonstrating hyperemic and edematous mucosa with bilateral grade 3 inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Cultures taken from the sinuses were negative for bacteria and fungi. PET scan at the same time did not suggest any tumor recurrence or involvement of the sinuses. Around the same time, he was incidentally noted to be in atrial fibrillation and subsequently cardioverted to sinus rhythm. His left ventricular ejection fraction was reduced to 35%.

Figure 1.

Maxillofacial CT without contrast shows prominent mucosal thickening of right greater than left maxillary and frontal sinuses with near complete opacification of the ethmoid air cells (arrow). No air fluid level or osseous erosion is seen.

In multidisciplinary discussion between oncology, rheumatology, and otolaryngology, it was thought that the sinus disease was inflammatory, likely attributable to prior immunotherapy, and additional immunosuppression was needed. A second course of adalimumab 40 mg every other week was cautiously initiated in light of the reduced ejection fraction, with complete resolution of sinus symptoms after just two doses. Joint symptoms improved, and the patient was able to return to exercise within one month of initiation of therapy. At last follow-up in February 2017, his melanoma remained in remission and he did not require further treatment with nivolumab since the second dose in December 2015. He had no sinus or articular symptoms with no sinus tenderness, nasal discharge or synovitis on examination. His ejection fraction had increased to 45–50%, although he did have one additional episode of atrial flutter requiring cardioversion. Adalimumab was spaced to every three weeks, with plan to space to every four weeks for potential discontinuation in February 2017.

Case 2

A 59-year-old female with a history of mild psoriasis (requiring only topical creams) was initially diagnosed with melanoma on the right leg in 2005 and underwent surgical resection. She subsequently developed lymphadenopathy in the right groin and was diagnosed with stage IIIB melanoma in 2012 by inguinal lymph node biopsy. She then entered a clinical trial comparing interferon to ipilimumab and was randomized to interferon treatment. In 2013, she was found to have a recurrence in a right iliac lymph node. She received adjuvant leukine (a melanoma vaccine) for treatment from 2013 to 2015. In 2014, a melanoma nodule was excised from her right thigh. In 2015, imaging revealed a new brain mass, and surgical resection revealed the lesion was metastatic melanoma. She subsequently received radiation with Cyberknife in January 2016. In March 2016, she received one dose of ipilimumab 1 mg/kg and nivolumab 3 mg/kg. She developed diarrhea that did not respond to 160 mg total of prednisone daily. She received two doses of infliximab 5 mg/kg in April and May to treat presumed colitis with resolution of diarrhea. In July 2016, she started on nivolumab monotherapy every two weeks.

Within days after her third nivolumab monotherapy infusion, the patient developed acute-onset of inflammatory arthritis and concomitant sinus pressure in the frontal and maxillary sinuses and nasal congestion. In contrast to previous episodes of sinusitis experienced prior to onset of immunotherapy, she did not have any fevers or nasal discharge. The arthritis involved her knees, ankles, feet, and fingers. She had a history of bilateral mild stiffness and pain in her knees from osteoarthritis but no prior joint swelling.

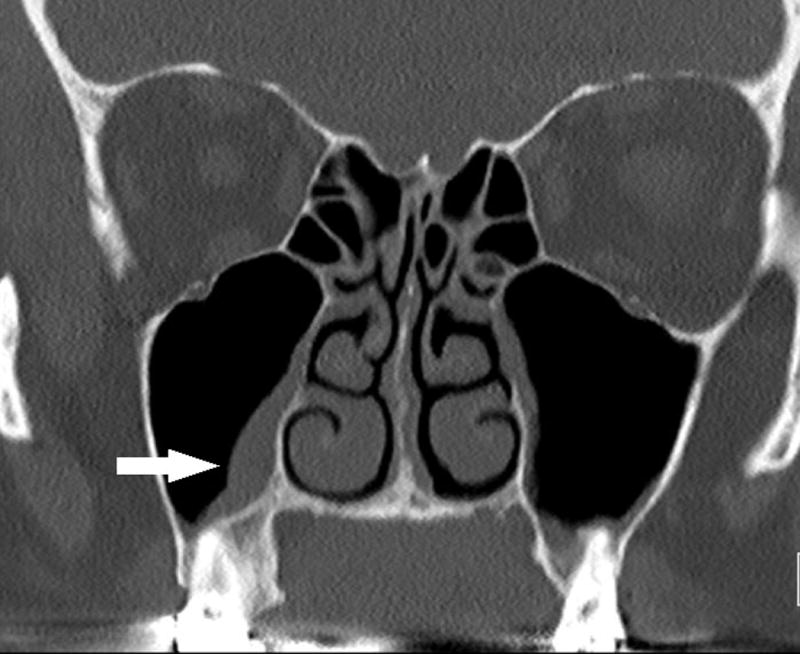

She was seen by otolaryngology and started on a week long course of doxycycline without improvement in her sinus pressure or nasal congestion. She was next evaluated by rheumatology about two weeks after the onset of joint and sinus symptoms on August 31, 2016. On initial rheumatologic examination, she had synovitis in her bilateral PIP joints, right wrist, bilateral knees, right ankle, and right 1st–3rd metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints. No rashes, psoriatic nail involvement, dactylitis or enthesitis were appreciated. Laboratory tests were notable for positive ANA (titer: 1:160 homogeneous and speckled), negative anti-CCP and rheumatoid factor. ANCAs were not checked initially. Anti-Ro (SS-A) and anti-La (SS-B) were negative. She was started on prednisone 20 mg daily for her inflammatory arthritis. Both her joint pain and stiffness and sinus pain and pressure improved on 20 mg of prednisone but did not resolve. Otolaryngology gave her a five day course of azithromycin for her sinus symptoms, which did not lead to additional improvement. Due to persistence of sinus pressure, imaging was obtained. A sinus CT showed inflammatory changes in maxillary sinuses and ethmoid air cells, right greater than left, with no air-fluid levels (figure 2a).

Figure 2.

a) Maxillofacial CT without contrast shows mucosal thickening of right (arrow) greater than left maxillary sinus. No air fluid level or osseous erosion is seen. b) Maxillofacial CT without contrast subsequent to adalimumab treatment shows decreased mucosal thickening in maxillary sinuses.

Given the lack of response of sinus pressure and nasal congestion to antibiotics and persistence of inflammatory arthritis, the patient was started on adalimumab therapy 40 mg weekly. She received four doses with total resolution of her inflammatory arthritis, sinus pressure and nasal congestion. Repeat imaging demonstrated improvement of mucosal thickening of maxillary sinuses (figure 2b). She unfortunately developed new neurologic symptoms and was found to have new metastatic brain lesions and growth of an existing metastatic thalamic lesion. Adalimumab was discontinued after four doses, and dexamethasone was started by radiation oncology. She did not receive nivolumab after she developed rheumatologic symptoms and was later started on trametinib. At last rheumatologic follow-up in December 2016, she had no signs or symptoms of inflammatory arthritis and no sinusitis since starting dexamethasone. Laboratory studies at that time were notable for a positive atypical p-ANCA (titer 1:160, negative MPO ELISA) and negative c-ANCA and PR3 ELISA.

Discussion

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are revolutionary in the field of oncology as novel agents utilizing inherent immune defenses to assist in cancer treatment. Inhibitory costimulatory molecules on T cells include cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death-1 (PD-1), as targeted in ipilimumab1 and nivolumab,2 respectively. Monoclonal antibodies directed against these checkpoint sites enhance the immune response by blocking inhibitory interactions between receptors on T cells and ligands on antigen presenting cells and tumor cells, thus leading to T cell activation3.

As a result of T-cell activation and downstream propagation of inflammatory pathways, the principal toxicities are immune-related adverse events (IRAEs).4 These immunologic-mediated toxicities have separate etiologies from traditional chemotherapeutic side effects with distinct treatment options.6 Common IRAEs include rash, pruritis, colitis, hepatitis, and endocrine disturbances.7 IRAEs with rheumatic complications like inflammatory arthritis seen in these two patients are less comprehensively described8, but have been described in case series and reports.

Here we describe two patients who developed aseptic sinusitis after immunotherapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab. To our knowledge, this is the first published report of sinusitis as an IRAE from anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 therapy. Case 1 was a 35-year-old man with multiple other IRAEs including colitis, inflammatory arthritis, conjunctivitis, urethritis, and vitiligo. His cardiac disease may also have been a manifestation of mild immune-mediated myocarditis, but without cardiac MRI or biopsy during the time of arrhythmias and decreased ejection fracture, this is unclear. Case 2 was a 59-year-old female who had additional inflammatory manifestations including colitis, inflammatory arthritis, and sicca syndrome. Both patients failed multiple antibiotic treatments and had no air-fluid levels on imaging to suggest a bacterial sinusitis. The patients both had significant and immediate response of their sinus symptoms after initiating adalimumab therapy. Case 2 had repeat imaging that showed an improvement of mucosal thickening of the paranasal sinuses after initiating anti-TNF therapy.

Several observations are notable from these cases. First, both patients were negative for c-ANCA antibodies, which are seen in another cause of non-infectious inflammatory sinusitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis). Case 2 had a positive atypical p-ANCA, which is not typically seen in GPA but can be seen in inflammatory bowel disease and other autoimmune disorders. In a case series of patients with inflammatory arthritis from nivolumab and/or ipilimumab all patients were negative for rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies9 traditionally associated with rheumatoid arthritis. That in many IRAEs, traditional autoantibodies are absent suggests one of two possibilities. Either novel autoantibodies are relevant to pathogenesis or the syndromes are not due to specific autoimmune responses and are more related to downstream inflammatory effects of T cell activation, that is, “autoinflammatory” rather than autoimmune. Second, both patients had improvement of their symptoms with TNF-inhibition. This is consistent with observations from the treatment of colitis10 and inflammatory arthritis9 due to immune checkpoint inhibitors. The utility of TNF-inhibition in these diverse clinical manifestations raises the question of how the pathogenesis of these adverse events overlap.

One limitation of this case report is that neither patient had a biopsy obtained of the sinuses for the specific immune infiltrate in the sinus mucosa to be characterized. That both patients failed to respond to courses of at least two antibiotics and improved rather than worsened with immunosuppression suggests an inflammatory and non-infectious etiology. Additionally, the role of laboratory analysis in immune-related sinusitis remains unclear. Case 2 had a positive atypical p-ANCA titer, though this was negative in case 1. The significance of this value in her presentation, as well as the role of other laboratory analysis in this diagnosis is uncertain.

Further investigation is warranted to evaluate the prevalence of sinusitis as a potential IRAE, as well as further understanding the role of corticosteroids, TNF inhibitors and other treatment options.

References

- 1.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappelli LC, Shah AA, Bingham CO. Cancer immunotherapy-induced rheumatic diseases emerge as new clinical entities. RMD Open. 2016;2:e000321. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2691–2697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fecher LA, Agarwala SS, Hodi FS, Weber JS. Ipilimumab and its toxicities: a multidisciplinary approach. Oncologist. 2013;18(6):733–743. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman CF, Proverbs-Singh TA, Postow MA. Treatment of the immune-related adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(10):1346–1353. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cappelli LC, Gutierrez AK, Bingham CO, 3rd, Shah AA. Rheumatic and musculoskeletal immune-related adverse events due to immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review of the literature. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016 Dec 20; doi: 10.1002/acr.23177. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cappelli LC, Gutierrez AK, Baer AN, et al. Inflammatory arthritis and sicca syndrome induced by nivolumab and ipilimumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Jan;76(1):43–50. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connor A, Marples M, Mulatero C, et al. Ipilimumab-induced colitis: experience from a tertirary referral center. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016 Jul;9(4):457–62. doi: 10.1177/1756283X16646709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]