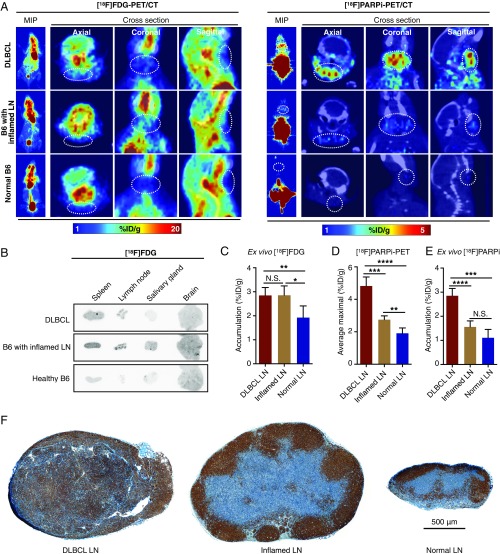

Fig. 5.

PARP1-targeted PET imaging differentiates malignant from inflamed lymph nodes. (A) Representative [18F]FDG PET (Left) and [18F]PARPi (Right) images of DLBCL mice (n = 3 for [18F]FDG; n = 5 for [18F]PARPi), B6 mice with inflamed lymph nodes (n = 3 for [18F]FDG; n = 5 for [18F]PARPi), and B6 mice with normal lymph nodes (n = 3 for [18F]FDG; n = 5 for [18F]PARPi). (B) Representative autoradiographic images of five selected tissues from the three groups of mice injected with [18F]FDG PET. (C) Ex vivo γ-counting of lymph node radioactivity from DLBCL mice (n = 5), B6 mice with inflamed lymph nodes (n = 5), and normal B6 (n = 5) injected with [18F]FDG. (D) Quantification of [18F]PARPi PET signal in lymph nodes from DLBCL mice (n = 5), B6 mice with inflamed lymph nodes (n = 5), and normal B6 mice (n = 4). Signals were calculated by averaging the maximal signals of five consecutive axial slices (1 mm thick) that cover superficial cervical lymph nodes. (E) Ex vivo γ-counting of lymph node radioactivity from DLBCL mice (n = 5), B6 mice with inflamed lymph nodes (n = 5), and normal B6 mice (n = 5) injected with [18F]PARPi. (F) Representative PARP1 immunostaining images of lymph nodes from DLBCL mice (n = 10), B6 mice with local inflammation (n = 10), and normal B6 mice (n = 10).