Abstract

Introduction

To evaluate the feasibility and safety of single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) for uncomplicated gallbladder in elderly patients.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis of 810 patients undergoing SILC from May 2009 to October 2016 at Osaka Police Hospital was performed, and the outcomes of the patients aged < 80 years and the patients ≥ 80 years were compared.

Results

The median operative times of patients <80 years and patients ≥80 years were 100 min and 110 min, respectively (p = 0.4). The conversion rates to a different operative procedure (multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy or open cholecystectomy) were 3% (22/763) of patients < 80 years and 0% of patients ≥ 80 years (p = 0.6). Perioperative complications were seen in 6% (46/763) of patients < 80 years and 17% (8/47) of patients ≥ 80 years (p < 0.05). Pneumonia was seen in 0% (0/763) of patients < 80 years and 4% (3/47) of patients ≥ 80 years (p < 0.05). There was no mortality in either group. The median postoperative hospital stay was 4 days for patients <80 years and 5 days for patients ≥80 years (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

SILC for uncomplicated gallbladder could be performed for patients ≥ 80 years with acceptable morbidity and mortality as compared with the previous reports, though the complication rate of patients ≥ 80 years was higher than that of patients < 80 years.

Keywords: Age, Octogenarian, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC)

Highlights

-

•

The operative time and the conversion rate of patients ≥80 years after single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy were comparable to those of patients <80 years.

-

•

The incidence of pneumonia was significantly higher in patients ≥80 years than in patients <80 years.

-

•

Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy could be performed in patients ≥80 years with acceptable morbidity and mortality.

1. Introduction

Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) is an emerging technique that is gaining increased attention due to its superior cosmesis, though there are many difficulties associated with a confined operating space, in-line positioning of the laparoscope, close proximity of the working instruments with limited triangulation, and limited range of motion of the laparoscope and instruments [1], [2], [3]. Regarding the patient characteristics that may particularly indicate or preclude the application of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), increased age is sometimes noted in the literature because of the need for an increased conversion rate to open cholecystectomy [4]. Although current literature frequently documents that experienced laparoscopic surgeons can perform LC safely for patients ≥80 years [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], there have been no report evaluating the feasibility and safety of performing SILC for elderly patients. Therefore, a large single-center database was retrospectively reviewed to evaluate the feasibility and safety of SILC for elderly patients by comparing patients aged <80 years and patients ≥80 years undergoing SILC.

2. Methods

2.1. Clinical setting

A retrospective analysis of patients who underwent SILC from May 2009 to October 2016 at Osaka Police Hospital was performed. A total of 810 patients were evaluated. The indications for SILC were uncomplicated gallbladder diseases such as gallstone, benign polyp, and chronic cholecystitis. Acute cholecystitis was excluded in this study. For the outcome analyses, patients were subdivided according to their age (<80 vs. ≥ 80 years).

2.2. Surgical technique

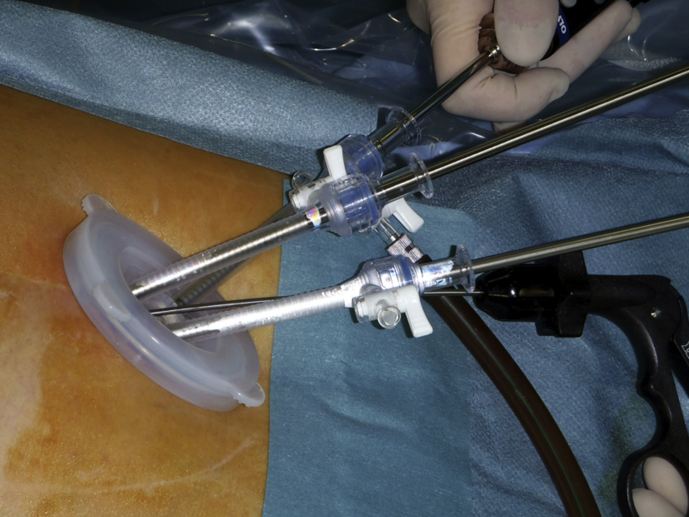

A single-access system enclosing working channels was introduced into the abdominal cavity via an incision of the muscular aponeurosis under visual control. Depending on the operating surgeon's choice and hospital supplies, several types of single-access systems (EZ access and Lap-Protector, Hakko Co., Ltd., Nagano, Japan; x-gate, Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan; SILS™, Covidien, Dublin, Ireland; OCTO™ port, Surgical Network Systems, Tokyo, Japan; and a surgical-glove technique that involves the use of a small plastic wound retractor inserted transumbilically with an attached surgical glove to prevent CO2 leakage with its fingers functioning as multiple ports for scopes and instruments) were used in this study. Recently, EZ access on the Lap Protector was typically used for the insertion of trocars. A flexible 5-mm laparoscope, standard straight laparoscopic instruments, and laparoscopic coagulation shears were used during the operations. In cases of difficult exposure, supplemental exposure systems (Mini Loop Retractor II, Covidien; or Endo Relief™, Hirata Precisions Co., Ltd., Chiba, Japan) were used according to the surgeon's preference and the clinical presentation (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) [12].

Fig. 1.

The Endo Relief and the three ports secured to the EZ Access for SILC.

Fig. 2.

The postoperative scar after SILC.

2.3. Data collection

Data on the patients' age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, history of previous abdominal surgery, operative time, bleeding volume, supplementary exposure system, conversion rate, perioperative complications, and postoperative hospital stay were obtained from the medical records.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Student's t-test and Fisher's exact probability test were used for the analyses of parametric and non-parametric data, as appropriate. Differences at p < 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (The Foundation for Statistical Computing); more precisely, it is a modified version of R commander designed to add statistical functions frequently used in biostatistics [13].

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes the patients' characteristics. Between May 2009 and October 2016, 810 patients underwent SILC at Osaka Police Hospital. These comprised 763 patients aged <80 years (94%) and 47 patients aged ≥ 80 years (6%). As expected, the mean age differed significantly between the patient groups. Mean BMI of the patients aged ≥80 years was significantly lower than that of the patients aged <80 years. There was a greater proportion of patients with an ASA score ≥3 among patients ≥80years (23%, 11/47) than among those aged < 80years (8%, 61/763), but the remaining baseline characteristics (sex and history of previous abdominal surgery) were comparable.

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics.

| Characteristics | Age <80 years (n = 763) | Age ≥ 80 years (n = 47) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 58 ± 13 | 83 ± 3 | <0.05 |

| Male sex | 380 (50) | 23 (49) | 1 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.5 ± 3.8 | 22.0 ± 3.0 | <0.05 |

| ASA score ≥ 3 | 61 (8) | 11 (23) | <0.05 |

| Previous abodominal surgery | 207 (27) | 17 (36) | 0.2 |

Datas are given mean ± SD or number (%).

SD, standard deviation.

BMI, body mass index.

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Table 2 shows the perioperative data. The median operative times of patients <80 years and patients ≥80 years, excluding the patients converted to either multiport or open surgery, were 100 min (range 35–301 min) and 110 min (range 42–219 min), respectively (p = 0.4). The median bleeding volumes in patients <80 years and patients ≥80 years, excluding the converted patients, were 0 ml (range 0–1400 ml) and 0 ml (range 0–550 ml), respectively (p = 0.9). The conversion rates to a different operative procedure (multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy or open cholecystectomy) were 3% (22/763) of patients < 80 years and 0% of patients ≥ 80 years (p = 0.6). Twenty-two cases of patients <80 years were converted: sixteen to multi-port surgery and six to open surgery. The reasons for conversion in the patients <80 years were (with some overlap): adhesion of the gallbladder in 11 cases; bleeding in 3 cases; Mirizzi syndrome in two cases; obesity in one case; disorientation of the cystic duct in one case; and a long distance from the umbilical wound to the gallbladder in one case. Perioperative complications were seen in 6% (46/763) of patients < 80 years and 17% (8/47) of patients ≥ 80 years (p < 0.05). Pneumonia was seen in 0% (0/763) of patients < 80 years and 4% (2/47) of patients ≥ 80 years (p < 0.05). There was no mortality in either group. The median postoperative hospital stay was 4 days (range 2–26 days) for patients < 80 years and 5 days (range 2–51 days) for patients ≥ 80 years (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Perioperative data.

| Age <80 years (n = 763) | Age ≥ 80 years (n = 47) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time, min | 100 (35–301) | 110 (42–219) | 0.4 |

| Bleeding volume, ml | 0 (0–1400) | 0 (0–550) | 0.9 |

| Supplementary exposure system | 658 (86) | 39 (83) | 0.5 |

| Conversion, total | 22 (3) | 0 | 0.6 |

| Multiple port surgery | 16 (2) | 0 | 0.6 |

| Open Surgery | 6 (1) | 0 | 1 |

| Complications, total | 46 (6) | 8 (17) | <0.05 |

| wound infection | 21 (3) | 2 (4) | 0.4 |

| incisional hernia of the umbilicus | 8 (1) | 2 (4) | 0.1 |

| prolonged inflammation response | 5 (0.7) | 1 (2) | 0.3 |

| intraabdominal abscess | 4 (0.5) | 0 | 1 |

| common bile duct stone | 3 (0.4) | 0 | 1 |

| injury of the intestine | 2 (0.3) | 1 (2) | 0.2 |

| pneumonia | 0 | 2 (4) | <0.05 |

| urinary tract infection | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 1 |

| bile duct injury | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 |

| Mortality | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, day | 4 (2–26) | 5 (2–51) | <0.05 |

Datas are given median (range) or number (%).

4. Discussion

In this study, there were two important clinical observations. First, the operative time and the conversion rate of patients ≥80 years after SILC were comparable to those of patients <80 years. Second, SILC could be performed in patients ≥80 years with acceptable morbidity and mortality.

First, the operative time and the conversion rate of patients ≥80 years after SILC were comparable to those of patients <80 years. Previous studies showed that elderly patients are more likely to be converted from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy [4], which might lead to a prolonged operative time. The reason for the high conversion rate in elderly patients was recurrent attacks of cholecystitis and a long history of gallstones, which might lead to both a fibrotic gallbladder and a serious adhesion between gallbladder and other organs, such as common bile duct and liver. Table 3 showed that the conversion rate of LC in patients ≥80 years was 2–27%. Contrary to these previous reports, SILC was performed for elderly patients with no conversion within a comparable operative time in the present study. In our department, which is currently one of the highest volume centers for SILS in the world, SILS is practically a standard laparoscopic approach for various procedures, such as cholecystectomy, colectomy, appendectomy, gastrectomy, acute abdomen, and hernioplasty [14]. Sufficient experience of SILS in a wide range of operative procedures and appropriate selection of patients with uncomplicated gallbladder might have led to the good operative performance of SILC in our department.

Table 3.

Summary of evaluating the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients ≥80 years.

| Author [reference] | Maxwell [5] | Uecker [6] | Brunt [7] | Hazzan [8] | Tambyraja [9] | Kwon [10] | Yetkin [11] | Wakasugi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication year | 1998 | 2001 | 2001 | 2003 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2017 |

| Number of patient ≥ 80 years | 105 | 16 | 70 | 67 | 117 | 45 | 11 | 47 |

| Age, year | 84 | NA | 83 | 84 | 83a | 83 | NA | 83 |

| Male sex | 35 (33) | NA | 25 (36) | 31 (46) | 38 (32) | 18 (40) | 5 (45) | 23 (49) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 22.0 |

| ASA score ≥ 3 | 75 (72) | NA | 43 (61) | 38 (57) | NA | NA | 9 (81) | 11 (23) |

| Previous abodominal surgery | 46 (60) | NA | 40 (57) | NA | NA | 11 (24) | NA | 17 (36) |

| Approach (multi/single- port) | multi | multi | multi | multi | multi | multi | multi | single |

| Operative time, min | 127 | NA | 106 | 94 | NA | 122 | NA | 110a |

| Conversion | 17 (16) | 2 (13) | 11 (16) | 5 (7) | 6 (5) | 1 (2) | 3 (27) | 0 |

| Complication, total | 35 (33) | 3 (19) | 18 (26) | 12 (18) | 26 (22) | 1 (2)b | 4 (36) | 8 (17) |

| Postoperative hospital stay, days | 4.4 | NA | 2.1 | 5.3 | 3a | NA | NA | 5a |

| Mortality | 5 (5) | 0 | 2 (3) | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data are given as means or numbers (%), unless otherwise specified.

NA: not applicable.

Median.

Confined to major complications.

Second, SILC in patients ≥80 years was performed with acceptable morbidity and mortality. Table 3 showed that the complication rate and the mortality of standard LC in patients ≥80 years were 2–36% and 0–5%, respectively. Yetkin et al.[11] reported that patients > 80 years had a 36% complication rate, which was significantly higher than that in younger groups. In the present study, the complication rate was 17% in patients ≥80 years, slightly better than the previous reports of the standard multi-port LC. The incidence of pneumonia was significantly higher in patients ≥80 years than in patients <80 years. We have to pay close attention to pneumonia in elderly patients undergoing SILC. The incidence of incisional hernia of the umbilicus was slightly higher in patients ≥80 years than in patients <80 years. A previous report showed that advanced age was associated with delayed would healing and could be a risk factor for incisional hernia [15]. It is mandatory to perform careful and meticulous repair of abdominal closure in elderly patients undergoing SILC.

Appropriate selection of patients and the operative procedure is important. SILC for uncomplicated gallbladder disease in octogenarians was a relatively safe procedure that could be accomplished with acceptable low morbidity and no mortality in the present study. Age ≥80 years alone should not be a contraindication to SILC. However, for extremely sick patients with severe comorbidity and high operative risk, prompt conversion of the operative procedure to multi-port LC or open cholecystectomy should be considered. This approach might reduce the rate of severe complications that might lead to mortality in elderly patients.

The present study has several limitations. First, this study was carried out at a single high-volume center and was retrospective in nature, acute cholecystitis was excluded, and patient selection bias might have been inevitable. For acute cholecystitis, skilled laparoscopic surgeons could perform SILC safely [16]. Second, this study included a limited number of elderly patients (6%, 47/810). With global population aging, the number of candidates for SILC among elderly patients is expected to increase gradually.

5. Conclusions

This report of a series of SILC for more than 600 patients performed in Osaka Police Hospital demonstrates that SILC for uncomplicated gallbladder could be performed in patients ≥80 years with acceptable morbidity and mortality.

Ethical approval

This protocol for the research project were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki in 1995 (as revised in Edinburgh 2000). This work has been reported in accordance with the PROCESS criteria [17]. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for the information to be included in our manuscript.

Sources of funding

No sources of funding.

Author contribution

Study design: MW.

Data collection:MW, KF.

Data analysis/interpretation: MW, MT.

Paper writing: MW, MT.

Data interpretation: All.

Review: MT, HA.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest to declared.

Research registry

researchregistry 2681.

Guarantor

Masaki Wakasugi.

References

- 1.Rivas H., Varela E., Scott D. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: initial evaluation of a large series of patients. Surg. Endosc. 2010;24:1403–1412. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0786-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curcillo P.G., 2nd, Wu A.S., Podolsky E.R. Single-port-access (SPA) cholecystectomy: a multi-institutional report of the first 297 cases. Surg. Endosc. 2010;24:1854–1860. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0856-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erbella J., Jr., Bunch G.M. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: the first 100 outpatients. Surg. Endosc. 2010;24:1958–1961. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0886-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang T.F., Guo L., Wang Q. Evaluation of preoperative risk factor for converting laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy: a meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:958–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maxwell J.G., Tyler B.A., Maxwell B.G. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in octogenarians. Am. Surg. 1998;64:826–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uecker J., Adams M., Skipper K., Dunn E. Cholecystitis in the octogenarian: is laparoscopic cholecystectomy the best approach? Am. Surg. 2001;67:637–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunt L.M., Quasebarth M.A., Dunnegan D.L., Soper N.J. Outcomes analysis of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the extremely elderly. Surg. Endosc. 2001;15:700–705. doi: 10.1007/s004640000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazzan D., Geron N., Golijanin D., Reissman P., Shiloni E. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in octogenarians. Surg. Endosc. 2003;17:773–776. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8529-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tambyraja A.L., Kumar S., Nixon S.J. Outcome of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients 80 years and older. World J. Surg. 2004;28:745–748. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7378-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon A.H., Matsui Y. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients aged 80 years and over. World J. Surg. 2006;30:1204–1210. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0413-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yetkin G., Uludag M., Oba S., Citgez B., Paksoy I. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in elderly patients. JSLS. 2009;13:587–591. doi: 10.4293/108680809X1258998404604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wakasugi M., Tanemura M., Tei M. Safety and feasibility of single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy in obese patients. Ann. Med. Surg. 2016;24(13):34–37. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2016.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakasugi M., Tei M., Omori T. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery as a teaching procedure: a single-center experience of more than 2100 procedures. Surg. Today. 2016;46:1318–1324. doi: 10.1007/s00595-016-1315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itatsu K., Yokoyama Y., Sugawara G. Incidence of and risk factors for incisional hernia after abdominal surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2014;101:1439–1447. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikumoto T., Yamagishi H., Iwatate M., Sano Y., Kotaka M., Imai Y. Feasibility of single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015;7:1327–1333. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i19.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Rajmohan S., Barai I., Orgill D.P., PROCESS Group Preferred reporting of case series in surgery; the PROCESS guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;36:319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]