Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to review the incidence and microbiology of acute postcataract surgery endophthalmitis in India.

Methods:

Systematic review of English-language PubMed referenced articles on endophthalmitis in India published in the past 21 years (January 1992–December 2012), and retrospective chart review of 2 major eye care facilities in India in the past 5 years (January 2010–December 2014) were done. The incidence data were collected from articles that described “in-house” endophthalmitis and the microbiology data were collected from all articles. Both incidence and microbiological data of endophthalmitis were collected from two large eye care facilities. Case reports were excluded, except for the articles on cluster infection.

Results:

Six of 99 published articles reported the incidence of “in-house” acute postcataract surgery endophthalmitis, 8 articles reported the microbiology spectrum, and 11 articles described cluster infection. The clinical endophthalmitis incidence was between 0.04% and 0.15%. In two large eye care facilities, the clinical endophthalmitis incidence was 0.08% and 0.16%; the culture proven endophthalmitis was 0.02% and 0.08%. Gram-positive cocci (44%-64.8%; commonly, Staphylococcus species), and Gram-negative bacilli (26.2%–43%; commonly Pseudomonas species) were common bacteria in south India. Fungi (16.7%-70%; commonly Aspergillus flavus) were the common organisms in north India. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (73.3%) was the major organism in cluster infections.

Conclusions:

The incidence of postcataract surgery clinical endophthalmitis in India is nearly similar to the world literature. There is a regional difference in microbiological spectrum. A registry with regular and uniform national reporting will help formulate region specific management guidelines.

Key words: Cataract surgery, endophthalmitis, India, microbiology

Acute postoperative endophthalmitis following cataract surgery is a dreaded complication. Fortunately, the incidence has declined in recent times after changes in surgical techniques, sterilization procedures, and better understanding of the risk factors.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7] The global reported incidence of postcataract endophthalmitis ranges from 0.02% to 0.26%.[1,2,3,4,5,6,8,9,10,11] There is good amount of data on the incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of postcataract endophthalmitis in the Western hemisphere.[12,13] Analyses of databases such as the Medicare and Medicaid have helped understand the epidemiology of postcataract endophthalmitis, and design treatment guidelines. Two other studies that have had global impacts on practices are the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study (EVS) for acute postcataract surgery bacterial endophthalmitis treatment and the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons study for cataract surgery endophthalmitis prophylaxis.[10,14,15]

India is a large and populous country with diverse geographical profile. Despite the fact that the data collection is not uniform across the country, many large eye care providers, both public and not-for-profit, have published several seminal reports that have formed the basis of this communication.[16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30] While this may not provide the real world scenario from the entire country, we believe that a literature review of the published Indian reports will indicate the trends on the incidence and microbiologic profiles from major regions of the country.

Methods

A detailed literature search was done using PubMed, Medline, OVID, Cochrane Library, Up to Date and Google Scholar databases with the search terms “cataract,” “postoperative,” “endophthalmitis,” “India,” and “microorganism.” The search period was restricted to 21 years from January 1992 to December 2012. The articles were reviewed to capture the incidence of acute endophthalmitis after cataract surgery. We defined postcataract surgery endophthalmitis as follows: clinical endophthalmitis as inflammation of the posterior segment as evidenced by slit lamp biomicroscopy, ophthalmoscopy and ultrasound, with or without hypopyon; and acute onset endophthalmitis as the one that occurred within 6 weeks following cataract surgery.[31] Articles describing the incidence of endophthalmitis occurring within an eye care facility's own setting (in-house), were selected to report incidence data. Microbiology spectrum was pooled from all articles that reported such data on endophthalmitis from both “in-house” and “referred” cases in the Indian setting. A systematic analysis was not possible due to an inadequate number of articles. Hence, we summarized information from all available reports and present the descriptive data in this communication.

Further, we reviewed the clinical case records and the records from the microbiology laboratories of 2 large eye care facilities, at Madurai and at Hyderabad from January 2010 to December 2014 to document change, if any, of the incidence and microbiology spectrum of in-house acute postcataract surgery endophthalmitis.

Results

Incidence of postcataract endophthalmitis

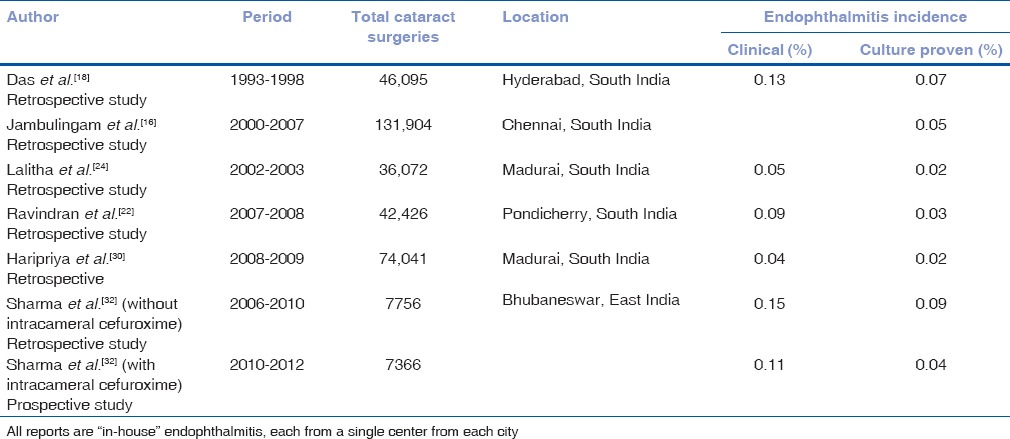

A total of 99 articles were published from the Indian setting during the 21-year study period. Six of them reported the incidence of postcataract “in-house” endophthalmitis.[16,18,22,24,30,32] The incidence of clinical acute postcataract endophthalmitis was from 0.04% to 0.15%, and the incidence of culture positive endophthalmitis was from 0.02% to 0.09% [Table 1]. The South Indian retrospective studies included the ones reported from Chennai, Hyderabad, Madurai, and Puducherry. One prospective study was reported from Bhubaneswar, East India.[32]

Table 1.

Reported incidence of endophthalmitis in India

Spectrum of microorganisms causing early postcataract endophthalmitis

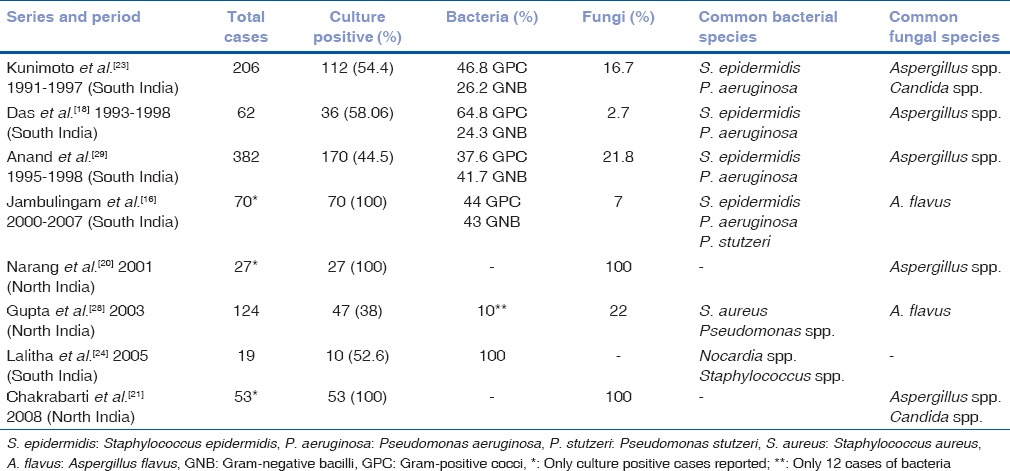

Eight major publications have reported the microbiological spectrum of postcataract surgery acute endophthalmitis that included in-house and referred cases [Table 2].[16,18,20,21,23,24,28,29] There was a major difference between different regions of the country. While there was a variable combination of bacteria and fungi, the fungal infection incidence varied from 2.7% to 70%, more often reported from the North than South India. The Gram-positive infection varied from 37.6% to 64.8% and the Gram-negative infection incidence varied from 24.3% to 43%.

Table 2.

Reported microbiology profile of postcataract surgery endophthalmitis, in-house and referred cases in India

Cluster infection

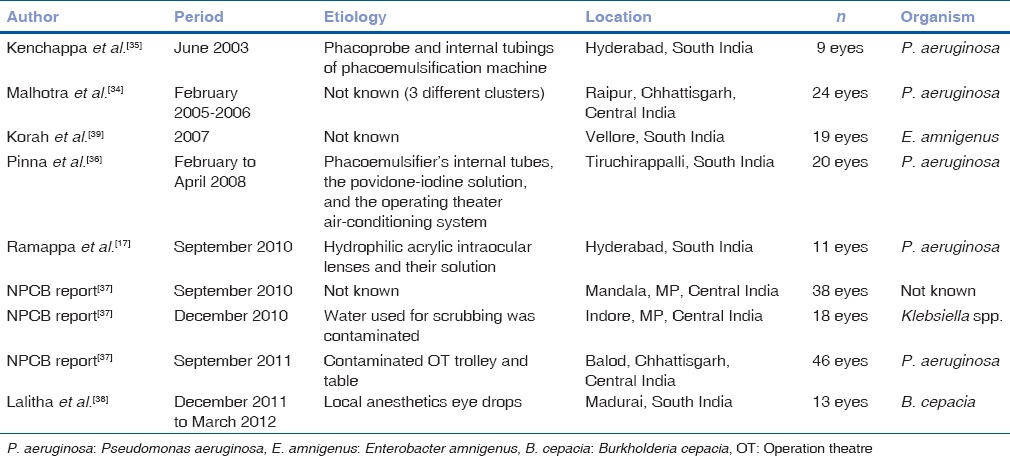

Cluster infection has been reported occasionally in Indian literature.[17,25,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] These included five reports from South India (Hyderabad, Madurai, Tiruchirappalli, and Vellore) and 6 reports from Central India [Table 3]. Pseudomonas (73.3%) or related species were the most common cause of infection as confirmed by culture and/or genotyping. In most instances, the source could be identified-the anesthetic drops, the phacoemulsification system, the fluid containing the hydrophilic lens, and the air conditioning system.

Table 3.

Reported cluster infection in India

Current trends

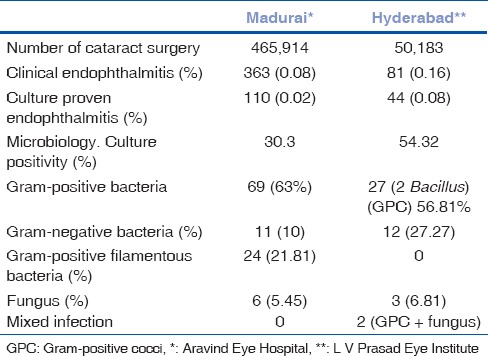

The incidence of in-house postcataract surgery acute endophthalmitis between the years 2010 and 2014 at Madurai (South India) was 0.08% (363 eyes of 465,914 cataract surgeries), culture positivity was 30.3%, and culture proven endophthalmitis was 0.02%. Bacteria were the commonest organisms and fungi accounted for 5% of instances. The incidence of in-house postcataract surgery acute endophthalmitis between the years 2010 and 2014 at Hyderabad (South India) was 0.16% (81 eyes of 50,183 cataract surgeries, excluding cluster endophthalmitis), culture positivity was 54.32% and culture proven endophthalmitis was 0.08%. Here, again bacteria were more common and fungi accounted for 6.52% instances [Table 4].

Table 4.

Five-year (2010-2014) endophthalmitis data of 2 large tertiary centers in India

Discussion

The endophthalmitis data (clinical, 0.04%–0.15%; culture proven, 0.02%–0.09%) generated from three major institutions in South India are nearly a decade old.[16,18,22,24] Institutions and practices constantly evolve in terms of surgical techniques and aseptic practices. Therefore, there is a possibility of a change in the incidence, the microbiology and antibiotic sensitivity patterns of postcataract endophthalmitis with time, and thus, there is a need for more recent reports. The incidence of postcataract in-house acute endophthalmitis in most recent 5 years (2010–2014) in 2 large eye care facilities was similar to that previously reported by these institutions.[18,22] Importantly, the cumulative number of surgeries performed in this period was more than ½ million though the rates remained similar. There was no change in the incidence or microbiologic spectrum in a 5-year period except that there was a significant decline in fungal infection in these two institutions.

Cataract surgery is one of the most widely performed surgical procedures in the world including India. Given that India performs approximately 6 million cataract surgeries per year applying a very conservative estimate of 0.08% endophthalmitis rate will translate to over 4,800 cases of endophthalmitis every year in the hospitals, excluding possible sporadic cluster infection. From this perspective alone, the current literature is not representative of the national scenario. We suspect that since the reporting of the in-house endophthalmitis may be associated with stigma and negative publicity, there might be reluctance to publishing such reports. A well-designed national registry, such as the Intelligent Research In Sight[40] and participation may be considered as a national priority.

Similar social issues apply to reporting of cluster endophthalmitis. These clusters may behave like outliers and may dramatically increase the rates of endophthalmitis from a particular geographical location. The documentation of such events and appropriate root cause analysis help not only to tide over the immediate crisis but also prevent similar future mishaps. In the Indian context, certain groups have indeed identified the offending agents, and thus modified the practice.

We found a discrepancy in reporting standards between different reports. While a few reports combined clinical and culture proven cases, others have reported only culture proven cases. Using culture proven cases only may lead to under reporting of the true incidence unless the culture positivity for the said laboratory is more than 80%. We believe, it is best to report both scenarios. In view of the reports of primary fungal infection, it is necessary to include fungus culture in Indian microbiology laboratories, as is the current practice.

Reports of higher fungal infections in both North and East India was a surprise, so also one report of higher Nocardia infection from South India. However, we recognize that some of these were referred rather than in-house cases and hence may not actually represent the true postcataract surgery endophthalmitis microbiology spectrum in the community. While we need a larger series from North India, two publications from Chennai (South India) have reported a reduction in the incidence of fungal postcataract surgery endophthalmitis.[16,29]

We found uniformity in the causative organism of cluster endophthalmitis. In two regions of the country – the Central and the South, Pseudomonas aeruginosa was the causative organism in nearly all instances. In addition, P. aeruginosa, be in cluster or isolated acute endophthalmitis was not as sensitive to ceftazidime as the EVS had reported.[15] This is a concern. Ceftazidime resistance has been reported from one center in South India.[41,42] Hence, it is prudent to review the infection and antibiotic sensitivity profile every 5 years.

The weaknesses of this report are the absence of visual outcomes, risk factors assessment, and lack of uniformity in clinical and microbiology reports in all publications. The strength of the study was an analysis of all available reports.

Conclusion

The incidence of postcataract surgery acute endophthalmitis in India is comparable to most of the developed world despite performing high volume cataract surgery. However, there is an urgent need for more reports from all institutes across different regions of India. A national registry with meticulous documentation of clinical and microbiology details will aid in developing region specific guidelines for the treatment and management of postcataract surgery endophthalmitis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Aravind Medical Research Foundation, Madurai and Hyderabad Eye Research Foundation, Hyderabad.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Khandekar R, Al-Motowa S, Alkatan HM, Karaoui M, Ortiz A. Incidence and determinants of endophthalmitis within 6 months of surgeries over a 2-year period at King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital, Saudi Arabia: A review. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22:198–202. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.154397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz G, Blum S, Leeva O, Axer-Siegel R, Moisseiev J, Tesler G, et al. Intracameral cefuroxime and the incidence of post-cataract endophthalmitis: An Israeli experience. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;253:1729–33. doi: 10.1007/s00417-015-3009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nam KY, Lee JE, Lee JE, Jeung WJ, Park JM, Park JM, et al. Clinical features of infectious endophthalmitis in South Korea: A five-year multicenter study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:177. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0900-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao K, Zhu Y, Zhu Z, Wu J, Liu Y, Lu Y, et al. The incidence of postoperative endophthalmitis after cataract surgery in China: A multicenter investigation of 2006-2011. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:1312–7. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friling E, Lundström M, Stenevi U, Montan P. Six-year incidence of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: Swedish national study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weston K, Nicholson R, Bunce C, Yang YF. An 8-year retrospective study of cataract surgery and postoperative endophthalmitis: Injectable intraocular lenses may reduce the incidence of postoperative endophthalmitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:1377–80. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Speaker MG, Menikoff JA. Prophylaxis of endophthalmitis with topical povidone-iodine. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1769–75. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day AC, Donachie PH, Sparrow JM, Johnston RL. Royal College of Ophthalmologists' National Ophthalmology Database. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists' National Ophthalmology Database Study of Cataract Surgery: Report 1, visual outcomes and complications. Eye (Lond) 2015;29:552–60. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao X, Liu A, Zhang J, Li Y, Jie Y, Liu W, et al. Clinical analysis of endophthalmitis after phacoemulsification. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42:844–8. doi: 10.3129/i07-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endophthalmitis Study Group, European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons. Prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: Results of the ESCRS multicenter study and identification of risk factors. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:978–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly SP, Mathews D, Mathews J, Vail A. Reflective consideration of postoperative endophthalmitis as a quality marker. Eye (Lond) 2007;21:1419–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du DT, Wagoner A, Barone SB, Zinderman CE, Kelman JA, Macurdy TE, et al. Incidence of endophthalmitis after corneal transplant or cataract surgery in a medicare population. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:290–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keay L, Gower EW, Cassard SD, Tielsch JM, Schein OD. Postcataract surgery endophthalmitis in the United States: Analysis of the complete 2003 to 2004 Medicare database of cataract surgeries. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:914–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doft BH, Barza M. Optimal management of postoperative endophthalmitis and results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1996;7:84–94. doi: 10.1097/00055735-199606000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han DP, Wisniewski SR, Wilson LA, Barza M, Vine AK, Doft BH, et al. Spectrum and susceptibilities of microbiologic isolates in the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71959-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jambulingam M, Parameswaran SK, Lysa S, Selvaraj M, Madhavan HN. A study on the incidence, microbiological analysis and investigations on the source of infection of postoperative infectious endophthalmitis in a tertiary care ophthalmic hospital: An 8-year study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010;58:297–302. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.64132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramappa M, Majji AB, Murthy SI, Balne PK, Nalamada S, Garudadri C, et al. An outbreak of acute post-cataract surgery Pseudomonas sp. endophthalmitis caused by contaminated hydrophilic intraocular lens solution. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:564–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das T, Hussain A, Naduvilath T, Sharma S, Jalali S, Majji AB, et al. Case control analyses of acute endophthalmitis after cataract surgery in South India associated with technique, patient care, and socioeconomic status. J Ophthalmol. 2012;2012:298459. doi: 10.1155/2012/298459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das T, Sharma S. Hyderabad Endophthalmitis Research Group. Current management strategies of acute post-operative endophthalmitis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2003;18:109–15. doi: 10.1076/soph.18.3.109.29804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narang S, Gupta A, Gupta V, Dogra MR, Ram J, Pandav SS, et al. Fungal endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: Clinical presentation, microbiological spectrum, and outcome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:609–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakrabarti A, Shivaprakash MR, Singh R, Tarai B, George VK, Fomda BA, et al. Fungal endophthalmitis: Fourteen years' experience from a center in India. Retina. 2008;28:1400–7. doi: 10.1097/iae.0b013e318185e943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravindran RD, Venkatesh R, Chang DF, Sengupta S, Gyatsho J, Talwar B, et al. Incidence of post-cataract endophthalmitis at Aravind Eye Hospital: Outcomes of more than 42,000 consecutive cases using standardized sterilization and prophylaxis protocols. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:629–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunimoto DY, Das T, Sharma S, Jalali S, Majji AB, Gopinathan U, et al. Microbiologic spectrum and susceptibility of isolates: Part I. postoperative endophthalmitis. endophthalmitis research group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:240–2. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lalitha P, Rajagopalan J, Prakash K, Ramasamy K, Prajna NV, Srinivasan M, et al. Postcataract endophthalmitis in South India incidence and outcome. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1884–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satpathy G, Patnayak D, Titiyal JS, Nayak N, Tandon R, Sharma N, et al. Post-operative endophthalmitis: Antibiogram & genetic relatedness between Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients and phacoemulsifiers. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:571–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambhav K, Mathai A, Bhatia K. Re: Fungal endophthalmitis: Fourteen years' experience from a center in India. Retina. 2009;29:1548. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181b86177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das T, Kunimoto DY, Sharma S, Jalali S, Majji AB, Nagaraja Rao T, et al. Relationship between clinical presentation and visual outcome in postoperative and posttraumatic endophthalmitis in South Central India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2005;53:5–16. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.15298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta A, Gupta V, Gupta A, Dogra MR, Pandav SS, Ray P, et al. Spectrum and clinical profile of post cataract surgery endophthalmitis in North India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2003;51:139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anand AR, Therese KL, Madhavan HN. Spectrum of aetiological agents of postoperative endophthalmitis and antibiotic susceptibility of bacterial isolates. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2000;48:123–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haripriya A, Chang DF, Reena M, Shekhar M. Complication rates of phacoemulsification and manual small-incision cataract surgery at Aravind Eye Hospital. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1360–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doft B. Focal Points: Modules for Clinicians. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 1997. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 27]. Endophthalmitis management. Available from: https://www.aao.org . [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma S, Sahu SK, Dhillon V, Das S, Rath S. Reevaluating intracameral cefuroxime as a prophylaxis against endophthalmitis after cataract surgery in India. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41:393–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pathengay A, Flynn HW, Jr, Isom RF, Miller D. Endophthalmitis outbreaks following cataract surgery: Causative organisms, etiologies, and visual acuity outcomes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1278–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malhotra S, Mandal P, Patanker G, Agrawal D. Clinical profile and visual outcome in cluster endophthalmitis following cataract surgery in Central India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:157–8. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.39126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kenchappa P, Sangwan VS, Ahmed N, Rao KR, Pathengay A, Mathai A, et al. High-resolution genotyping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains linked to acute post cataract surgery endophthalmitis outbreaks in India. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2005;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinna A, Usai D, Sechi LA, Zanetti S, Jesudasan NC, Thomas PA, et al. An outbreak of post-cataract surgery endophthalmitis caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2321–6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Programme for Control of Blindness, India Newsletter. 2011. Oct-Dec. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 30]. Available from: http://www.npcb.nic.in/writereaddata/mainlinkfile/File243.pdf .

- 38.Lalitha P, Das M, Purva PS, Karpagam R, Geetha M, Lakshmi Priya J, et al. Postoperative endophthalmitis due to Burkholderia cepacia complex from contaminated anaesthetic eye drops. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:1498–502. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korah S, Braganza A, Jacob P, Balaji V. An “epidemic” of post cataract surgery endophthalmitis by a new organism. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:464–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.36486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Academy of Ophthalmology. IRIS Registry. 2012. [Last accessed on 2017 Mar 12]. Available from: https://www.aao.org/iris-registry .

- 41.Jindal A, Pathengay A, Khera M, Jalali S, Mathai A, Pappuru RR, et al. Combined ceftazidime and amikacin resistance among gram-negative isolates in acute-onset postoperative endophthalmitis: Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibilities, and visual acuity outcome. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3:62. doi: 10.1186/1869-5760-3-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dave VP, Pathengay A, Nishant K, Pappuru RR, Sharma S, Sharma P, et al. Clinical presentations, risk factors and outcomes of ceftazidime-resistant gram-negative endophthalmitis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;45:254–60. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]