Abstract

The circulating soluble tumor necrosis factor (sTNF) and sTNF-receptor (R) 1 and -R2 have known as septic biomarker. The pungent component of capsicum, capsaicin (Cap), has several associated physiological activities, including anti-oxidant, anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory effects. The aim of this study was to elucidate the effect of Cap on circulating sTNF and sTNF-R1 and -R2 in vivo using lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated mice. LPS (20 mg/kg, ip)-treated group was significantly increased circulating sTNF, sTNF-R1, and -R2 and TNF-α mRNA expression levels compared to the vehicle group. Treatment with LPS (20 mg/kg, ip) + Cap (4 mg/kg, sc)-treated group was significantly decreased both circulating sTNF levels (after 1 h only) and TNF-α mRNA expression (after 6 h) compared to the LPS-treated group. There is an early increase in circulating sTNF, sTNR-R1, and -R2 observed in the LPS-treated mice. Since Cap inhibits this initial increase as biomarkers, circulating sTNF, it is considered a potent treatment option for TNF-α-related diseases, such as septicemia. In conclusion, Cap interferes with TNF-α mRNA transcription and exerts an inhibiting effect on TNF-α release from macrophages in the early phase after LPS stimulation. Thus, Cap is considered a potent agent for the treatment of TNF-α-related diseases, such as septicemia.

Abbreviations: Cap, capsaicin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NO, nitric oxide; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; TACE, TNF-converting enzyme; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; TNF-R, tumor necrosis factor-receptor

Keywords: ADAM-17, Capsaicin, Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Soluble tumor necrosis (sTNF), Soluble tumor necrosis factor-receptor 1 and 2 (TNF-R 1 and 2), TNF-converting enzyme (TACE)

1. Introduction

The pungent component of capsicum, capsaicin (Cap), has several associated physiological activities, including anti-oxidant, anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory effects [1], [2], [3].

LPS is an outer membrane component of Gram-negative bacteria and has been reported to activate NF-κB via toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which is present on antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells or macrophages [4], releasing pro-inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, interleukins (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10) [5], [6], and nitric oxide (NO) [7]. Macrophages can also release TNF-α (as soluble TNF [sTNF]) [8], which mediates its biological activities through binding to type 1 and 2 TNF receptors (TNF-R1 and -R2) [9], [10]. In addition, TNF-R2, the principal mediator of the effects of TNF-α on cellular immunity, may cooperate with TNF-R1 in the killing of nonlymphoid cells [11]. When TNF-R1 and/or -R2 are stimulated by TNF-α, the extracellular portions of transmembrane proteins are cleaved, soluble ectodomains are released from the cell surface by a sheddase known as TNF-converting enzyme (TACE) [12], and sTNF is neutralized by the sTNF-Rs [13]. After cell stimulation by various stimuli, including TNF-α itself, these two receptors can be proteolytically cleaved by TACE [14] into two soluble forms, sTNF-R1 and sTNF-R2, which show prolonged elevation in the circulation of patients with various inflammatory diseases such as septicemia, leukemia, hepatitis C virus infection, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and congestive heart failure [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]. Furthermore, increased circulating levels of sTNF-R1 and -2 have been reported in a rat model of CCL4 induced-liver injury [23].

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of Cap on circulating TNF-α (sTNF), sTNF-R1, and -R2 levels in LPS-treated mice. The expression of TNF-α, sTNF-R1 and -R2 proteins and mRNA were also examined in blood at different time points.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

LPS (Escherichia coli, 055:B55, Lot No. 114K4107) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, Co. (MO, USA), and Cap (98% purity) was provided by Maruishi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Other reagents used were commercially available extra-pure grade chemicals.

2.2. Animals

Male BALB/c mice (age, 8–10 weeks; weight, 21–26 g; Japan SLC, Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) were used. They were housed for at least one week under controlled environmental conditions (temperature, 24 ± 1 °C; humidity, 55 ± 10%; light cycle, 6:00–18:00) with free access to solid food (NMF, Oriental yeast Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and water. All experimental procedures were conducted according to the guidelines for the use of experimental animals and animal facilities established by Osaka University of Pharmaceutical Sciences.

2.3. Treatment of mice

LPS was dissolved in 2 mg/ml of physiological saline (Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and diluted to 1 mg/ml in physiological saline. Cap was dissolved in 1% ethanol + 1% Tween 20 in physiological saline. LPS (20 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally (ip) and 4 mg/kg Cap was administered subcutaneously (sc) to the backs of the mice 5 min after LPS administration.

2.4. Measurement of circulating sTNF, sTNF-R1, and sTNF-R2 levels

Mice were divided into four groups: vehicle group, LPS group, Cap group, and LPS + Cap group. The animals were sacrificed under anesthesia for the following procedures at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h after LPS administration. Whole blood was taken from the abdominal aorta of the mice. The samples were centrifuged, and the supernatant was measured. Measurements were performed using Quantikine® Immunoassay Mouse TNF-α, Quantikine® Immunoassay Mouse sTNFRI, and Quantikine® Immunoassay Mouse sTNFRII (R&D Systems, Inc., MN, USA). Within 30 min, absorbance was measured at 450 nm and 570 nm using a plate reader (Labsystems Multiscan MS; Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The measured value of the vehicle group was defined as the control value. The limits of detection of sTNF, sTNF-R1, and sTNF-R2 levels were 5.1, 5.0, and 5.0 pg/ml, respectively.

2.5. Measurement of circulating TNF-α, TNF-R1, and TNF-R2 mRNA expression (derived from macrophages) levels in whole blood

Whole blood was taken from the abdominal aorta of the mice under anesthesia at 0.5, 1, 3, 6, and 9 h after LPS administration. Total RNA was extracted from 300 μl of whole blood using a total RNA extraction kit (PureLink™ Total RNA Blood Purification Kit for isolating total RNA from whole Blood; Invitrogen Corporation, CA, USA). Synthesis of cDNA was performed by reverse transcription using total RNA solution (PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit; Takara Bio Inc, Shiga, Japan), and mRNA was measured using a thermal cycler (LightCycler®, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). The results were adjusted using glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and 18s rRNA, a housekeeping gene, as the internal standards.

2.6. Data analysis

Values are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using Tukey's test. A significant difference was determined as P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Circulating sTNF, sTNF-R1, and sTNF-R2 levels

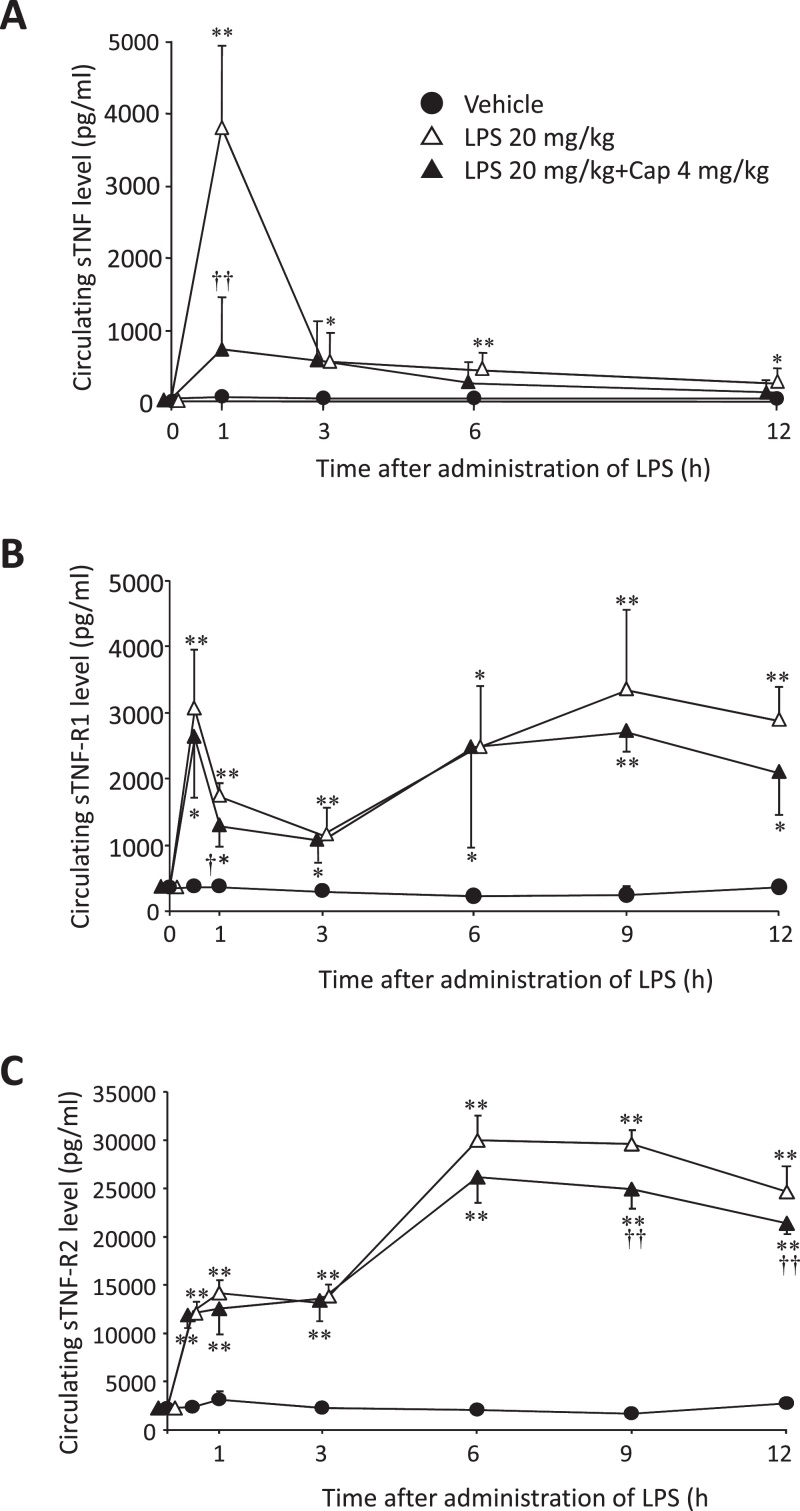

The circulating sTNF level significantly increased in the LPS group 1 h after LPS administration compared to both the vehicle (P < 0.01, Fig. 1A) and LPS + Cap (P < 0.01, Fig. 1A) groups (n = 3–4). There was no significant difference in the circulating sTNF levels between the vehicle and LPS + Cap groups (Fig. 1A). From 3 h to 12 h after LPS stimulation, circulating sTNF levels in the LPS group significantly increased compared to the vehicle group (P < 0.05 or 0.01, Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

The chronological changes in circulating soluble tumor necrosis factor (sTNF), sTNF-receptor 1 (R1), and sTNF-R2 levels. Mice were treated with or without lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 20 mg/kg, and were treated with LPS 20 mg/kg and capsaicin (Cap) 4 mg/kg. (A) Circulating sTNF level mice. Data shows mean ± SD (n = 3–4). (B) Circulating sTNF-R1 level in mice. Data shows mean ± SD (n = 3–4). (C) Circulating sTNF-R2 level in mice. Data shows mean ± SD (n = 3–4). *P < 0.05, compared to the vehicle group. **P < 0.01, compared to the vehicle group. †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01, compared with LPS group.

Both the circulating sTNF-R1 and -R2 levels in the LPS and LPS + CAP groups significantly increased from 0.5 h to 12 h after LPS administration, compared to the vehicle group (P < 0.05 or 0.01, Fig. 1B and C). No such differences in circulating sTNF-R1 levels were observed between the LPS group and the LPS + Cap group (Fig. 1B and C). But at 0.5 h after LPS administration, sTNF-R1 levels in the LPS + Cap group were significantly decreased, compared to the LPS group (P < 0.05, Fig. 1B).

At 9 h and 12 h after LPS administration, sTNF-R2 levels in the LPS + Cap group were significantly decreased compared to the LPS group (P < 0.01, Fig. 1C).

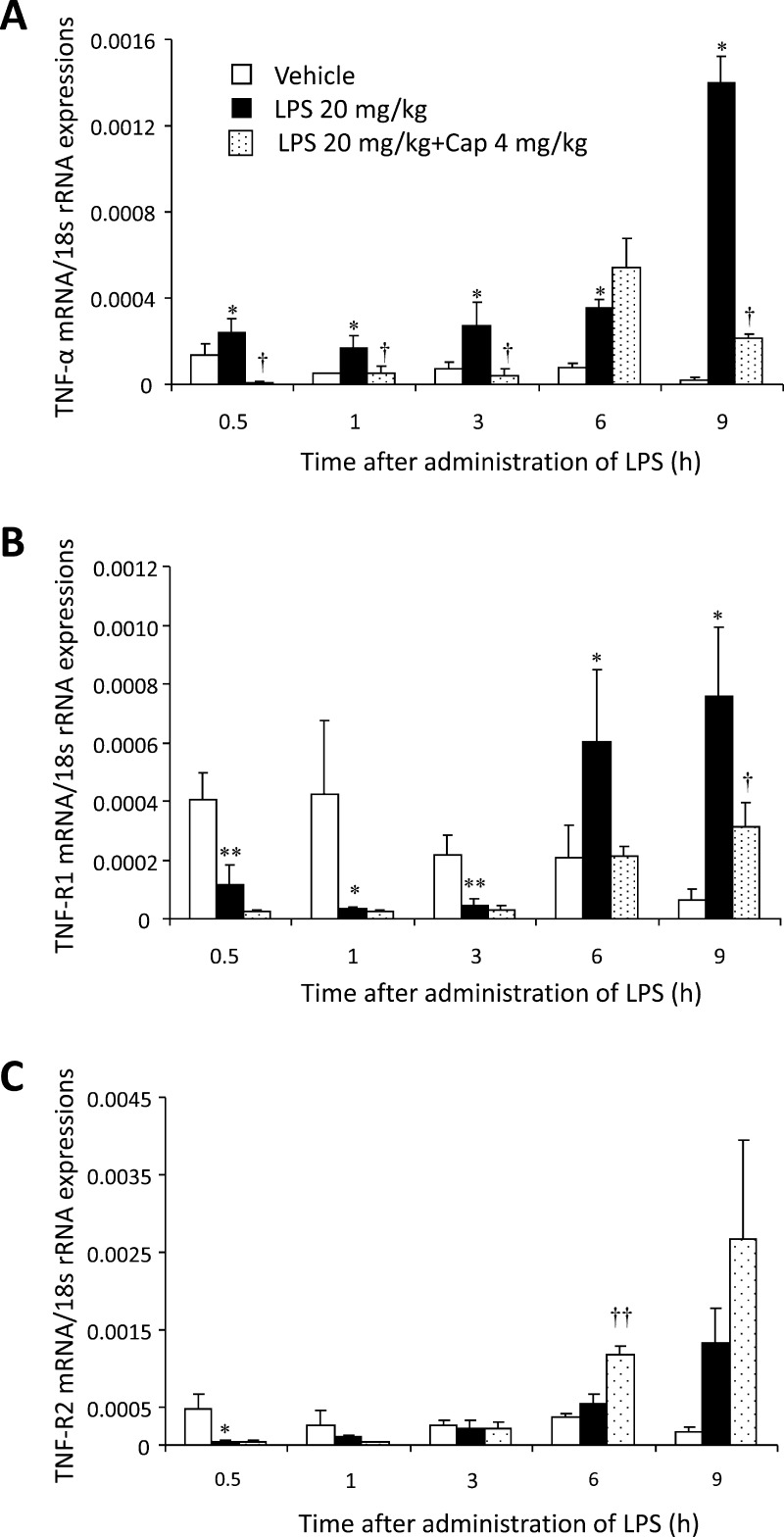

3.2. Expression of circulating TNF-α, TNF-R1, and TNF-R2 mRNA derived from leucocytes

Compared to the vehicle group, no significant change was observed in the circulating TNF-α, TNF-R1, or TNF-R2 mRNA expression levels in the Cap group (data not shown). The circulating TNF-α mRNA expression level in the LPS group was significantly increased 0.5, 1, 3, 6, and 9 h after LPS administration (P < 0.05, Fig. 2A) compared to the vehicle group. Despite this, the circulating TNF-α mRNA expression level in the LPS + Cap group significantly decreased 0.5, 1, 3, and 9 h after LPS administration compared to the vehicle group (P < 0.05, Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

The chronological changes in circulating tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, TNF-receptor (TNF-R) 1 and TNF-R2 mRNA expression levels. Mice were treated with or without lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 20 mg/kg, and were treated with LPS 20 mg/kg and capsaicin (Cap) 4 mg/kg. (A) Circulating TNF-α mRNA expression level in mice. Data shows mean ± SD (n = 3). (B) Circulating TNF-R1 mRNA expression level in mice. Data shows mean ± SD (n = 3). (C) Circulating TNF-R1 mRNA expression level in mice. Data shows mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, compared to the vehicle group (without LPS administration), **P < 0.01, compared to the vehicle group (without LPS administration), †P < 0.05, compared to the LPS group, ††P < 0.01, compared to the LPS group.

The circulating TNF-R1 mRNA expression level in the LPS group significantly decreased 0.5, 1, and 3 h after LPS administration compared to the vehicle group (P < 0.05 or 0.01, Fig. 2B), even though they were significantly increased 6 h and 9 h after LPS administration compared to the vehicle group (P < 0.05, Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the circulating TNF-R1 mRNA expression level in the LPS + Cap group significantly increased 9 h after LPS administration compared with the vehicle group (P < 0.05, Fig. 2B).

The circulating TNF-R2 mRNA expression level in the LPS group significantly decreased 0.5 h after LPS administration compared to the vehicle group (P < 0.05, Fig. 2C). Despite this, the circulating TNF-R2 mRNA expression level in the LPS + Cap group significantly increased 6 h after LPS administration compared to the vehicle group (P < 0.01, Fig. 2C).

4. Discussion

Cap has been previously reported to improve the survival rate of LPS-treated mice [24], although the precise mechanism of the effect of Cap was not explained. The aim of this study was to elucidate the effect of Cap on circulating biomarkers, sTNF, sTNF-R1, and -R2 levels in LPS-treated mice.

Increased circulating sTNF-R1 and -R2 levels have been reported in patients with hepatitis C virus infection [18], and increased circulating sTNF-R2 levels in patients with congestive heart failure [17], obesity-impaired glucose tolerance [25], and leukemia [20], [22]. In this study, we confirmed that the circulating sTNF-R2 levels in plasma were approximately 10-fold higher than the circulating sTNF-R1 levels at each time point [23]. Since the circulating sTNF, sTNF-R1, and -R2 levels are the initial signals of an immune response, plasma changes in them could represent a biomarker detectable at an earlier stage than C-reactive proteins, leukocytes, and fever during sepsis or systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). These values thus are known biomarkers of septic shock [15].

At the time to maximum plasma concentration (Tmax; 1 h after LPS administration), circulating sTNF level in LPS group was significantly increased compared to these levels in vehicle or LPS + Cap groups. The level declined from 3 h to 12 h, but the level in the LPS group significantly increased compared to the vehicle group (Fig. 2A). While the TNF-α mRNA expression level derived from blood (including leucocytes) in the LPS group also significantly increased from 0.5 h to 9 h compared with the vehicle or LPS + Cap groups (Fig. 2A). This difference may be due to the release of stored membrane-bound TNF-α (mTNF) from macrophages 1 h after LPS stimulation [26]. Following LPS stimulation (in inflammation), TNF-α is primarily expressed as a 26 kDa type II transmembrane protein, mTNF and is subsequently cleaved by the metalloproteinase-disintegrin TNF-α converting enzyme (TACE, also known as ADAM-17) into the secreted 17 kDa monopeptide TNF-α (sTNF) [12], [14], [27]. Similarly, TACE, a member of the ADAM family of zinc metalloproteinases, modulates the generation of sTNF-R1 and -R2 by proteolytically cleaving the TNF-R1 and -R2 ectodomains, respectively [27]. Following a single LPS stimulation, the circulating sTNF level in the LPS group significantly and continuously increased from 3 h to 12 h compared to the vehicle group. At 1 h after LPS stimulation the circulating sTNF was considered to be derived from mTNF. From 3 h onwards after LPS stimulation, the circulating sTNF level was considered to be derived from TNF-α mRNA induced by LPS. While both sTNF-R1 and -R2 mRNA levels were not differences among vehicle, LPS, and LPS + Cap groups from 0.5 h to 12 h after LPS stimulation.

Furthermore, the circulating sTNF-R2 level was approximately 10-fold that of sTNF-R1 in this study, similar to these levels of carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury rats [23]. TNF-R1 has been reported to bind to sTNF more frequently than TNF-R2 [26]; therefore, we assumed that binding with TNF-α after LPS stimulation neutralized TNF-R1, resulting in decreased circulation of both sTNF and sTNF-R1.

Regarding the effects of Cap on sTNF, the sTNF level in the LPS + Cap group was significantly depressed by Cap 1 h after LPS stimulation compared to the LPS group (Fig. 1A). Cap, therefore, has the potential to depress the production of sTNF via membrane stability. Furthermore, Cap significantly depressed TNF-α mRNA from 0.5 h to 9 h (Fig. 2A). Cap was assumed to depress the increase in TNF-α mRNA in LPS-treated mice. The above-mentioned results show that Cap has the potential to suppress TNF-α production following LPS-stimulation [28], [29].

Our results assume the following two mechanisms for the anti-TNF-α effect of Cap: firstly, Cap exerts a release-inhibiting effect on circulating sTNF from macrophages in the early phase of septicemia; secondly, Cap interferes with TNF-α mRNA transcription. Since Cap inhibits the initial increase in circulating sTNF, it is considered a potent treatment option for TNF-α-related diseases, such as septicemia.

5. Conclusion

There is an early increase in circulating sTNF, sTNR-R1, and -R2 observed in the LPS-treated mice. Cap interferes with TNF-α mRNA transcription and exerts an inhibiting effect on TNF-α release from macrophages in the early phase after LPS stimulation. Thus, Cap is considered a potent agent for the treatment of TNF-α-related diseases, such as septicemia.

Transparency document

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Maruishi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. for the gift of Cap.

Footnotes

Available online 22 October 2014

References

- 1.Demirbilek S., Ersoy M.O., Demirbilek S., Karaman A., Gürbüz N., Bayraktar N., Bayraktar M. Small-dose capsaicin reduces systemic inflammatory responses in septic rats. Anesth. Analg. 2004;99(5):1501–1507. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000132975.02854.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalia N.P., Mahajan P., Mehra R., Nargotra A., Sharma J.P., Koul S., Khan I.A. Capsaicin, a novel inhibitor of the NorA efflux pump, reduces the intracellular invasion of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67(10):2401–2408. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim C.S., Kawada T., Kim B.S., Han I.S., Choe S.Y., Kurata T., Yu R. Capsaicin exhibits anti-inflammatory property by inhibiting IkB-a degradation in LPS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages. Cell. Signal. 2003;15:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunzendorfer S., Lee H.K., Soldau K., Tobias P.S. Toll-like receptor 4 functions intracellularly in human coronary artery endothelial cells: roles of LBP and sCD14 in mediating LPS responses. FASEB J. 2004;18:1117–1119. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1263fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jayaraman P., Sada-Ovalle I., Nishimura T., Anderson A.C., Kuchroo V.K., Remold H.G., Behar S.M. IL-1β promotes antimicrobial immunity in macrophages by regulating TNFR signaling and caspase-3 activation. J. Immunol. 2013;190:4196–4204. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu W., Roos A., Schlagwein N., Woltman A.M., Daha M.R., Kooten V.C. IL-10-producing macrophages preferentially clear early apoptotic cells. Blood. 2006;107:4930–4937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacMicking J., Xie Q.W., Nathan C. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997;15:323–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kriegler M., Perez C., DeFay K., Albert I., Lu S.D. A novel form of TNF/cachectin is a cell surface cytotoxic transmembrane protein: ramifications for the complex physiology of TNF. Cell. 1988;53(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idriss H.T., Naismith J.H. TNF alpha and the TNF receptor superfamily: structure–function relationship(s) Microsc. Res. Tech. 2000;50:184–195. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20000801)50:3<184::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lien E., Liabakk N.B., Johnsen A.C., Nonstad U., Sundan A., Espevik T. Polymorphonuclear granulocytes enhance lipopolysaccharide-induced soluble p75 tumor necrosis factor receptor release from mononuclear cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25:2714–2717. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beltinger C.P., White P.S., Maris J.M., Sulman E.P., Jensen S.J., LePaslier D., Stallard B.J., Goeddel D.V., de Sauvage F.J., Brodeur G.M. Physical mapping and genomic structure of the human TNFR2 gene. Genomics. 1996;35(1):94–100. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshida A., Kohchi C., Inagawa H., Nishizawa T., Hori H., Soma G. A soluble 17 kDa tumour necrosis factor (TNF) mutein, TNF-SAM2, with membrane-bound TNF-like biological characteristics. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:4003–4008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Modzelewski B. Soluble TNF p55 and p75 receptors in the development of sepsis syndrome. Pol. Merkuriusz Lek. 2003;14:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine S.J., Adamik B., Hawari F.I., Islam A., Yu Z.X., Liao D.W., Zhang J., Cui X., Rouhani F.N. Proteasome inhibition induces TNFR1 shedding from human airway epithelial (NCI-H292) cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005;289:233–243. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00469.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brauner J.S., Rohde L.E., Clausell N. Circulating endothelin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α: early predictors of mortality in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:305–313. doi: 10.1007/s001340051154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao H., Wang J., Xi L., Røe O.D., Chen Y., Wang D. Dysregulated atrial gene expression of osteoprotegerin/receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK)/RANK ligand axis in the development and progression of atrial fibrillation. Circ. J. 2011;75:2781–2788. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrari R., Bachetti T., Confortini R., Opasich C., Febo O., Corti A., Cassani G., Visioli O. Tumor necrosis factor soluble receptors in patients with various degrees of congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1995;92:1479–1486. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.6.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplanski G., Marin V., Maisonobe T., Sbai A., Farnarier C., Ghillani P., Durand J.M., Harle J.R., Bongrand P., Piette J.C., Cacoub P. Increased soluble p55 and p75 tumour necrosis factor-a receptors in patients with hepatitis C-associated mixed cryoglobulinaemia. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2002;127:123–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKenna S.D., Feger G., Kelton C., Yang M., Ardissone V., Cirillo R., Vitte P.A., Jiang X., Campbell R.K. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-soluble high-affinity receptor complex as a TNF Antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;322:822–828. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navarro S.L., Brasky T.M., Schwarz Y., Song X., Wang C.Y., Kristal A.R. Reliability of serum biomarkers of inflammation from repeated measures in healthy individuals. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1167–1170. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pajkrt D., Manten A., van der Poll T., Tiel-van Buul M.M., Jansen J., Wouter J., ten C., van Deventer S.J.H. Modulation of cytokine release and neutrophil function by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor during endotoxemia in humans. Blood. 1997;90:1415–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trentin L., Pizzolo G., Zambello R., Agostini C., Morosato L., Sancetta R., Adami F., Vinante F., Chilosi M., Gallati H. Leukemic cells in hairy cell leukemia and B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia release soluble TNF receptors. Leukemia. 1995;9(6):1051–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ijiri Y., Kato R., Sadamatsu M., Takano M., Okada Y., Tanaka K., Hayashi T. Chronological changes in circulating levels of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors 1 and 2 in rats with carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury. Toxicology. 2014;316:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsukura Y., Takabatake Y., Nakazato H., Kato R., Ijiri Y., Tanaka K. Capsaicin improves survival rate in mice with lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxin shock. Circ. Cont. 2007;28:307–313. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dzienis-Straczkowska S., Straczkowski M., Szelachowska M., Stepien A., Kowalska I., Kinalska I. Soluble tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptors in young obese subjects with normal and impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:875–880. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grell M., Douni E., Wajant H., Löhden M., Clauss M., Maxeiner B., Georgopoulos S., Lesslauer W., Kollias G., Pfizenmaier K., Scheurich P. The transmembrane form of tumor necrosis factor is the prime activating ligand of the 80 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell. 1995;83:793–802. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy P., Slack J.L., Davis R., Cerretti D.P., Kozlosky C.J., Blanton R.A., Shows D., Peschon J.J., Black R.A. Functional analysis of the domain structure of tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(19):14608–14614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen C.W., Lee S.T., Wu W.T., Fu W.M., Ho F.M., Lin W.W. Signal transduction for inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 induction by capsaicin and related analogs in macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;140:1077–1087. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park J.Y., Kawada T., Han I.S., Kim B.S., Goto T., Takahashi N., Fushiki T., Kurata T., Yu R. Capsaicin inhibits the production of tumor necrosis factor alpha by LPS-stimulated murine macrophages, RAW 264.7: a PPARγ ligand-like action as a novel mechanism. FEBS Lett. 2004;572:266–270. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.