Abstract

Tributyltin (TBT) is a highly toxic pollutant present in many aquatic ecosystems. Its toxicity in mollusks strongly affects their performance and survival. The main purpose of this study was to elucidate the mechanisms of TBT toxicity in clam Ruditapes decussatus by evaluating the metabolic responses of heart tissues, using high-resolution magic angle-spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (HRMAS NMR), after exposure to TBT (10−9, 10−6 and 10−4 M) during 24 h and 72 h. Results show that responses of clam heart tissue to TBT exposure are not dose dependent. Metabolic profile analyses indicated that TBT 10−6 M, contrary to the two other doses tested, led to a significant depletion of taurine and betaine. Glycine levels decreased in all clam groups treated with the organotin. It is suggested that TBT abolished the cytoprotective effect of taurine, betaine and glycine thereby inducing cardiomyopathie. Moreover, results also showed that TBT induced increase in the level of alanine and succinate suggesting the occurrence of anaerobiosis particularly in clam group exposed to the highest dose of TBT. Taken together, these results demonstrate that TBT is a potential toxin with a variety of deleterious effects on clam and this organotin may affect different pathways depending to the used dose.

The main finding of this study was the appearance of an original metabolite after TBT treatment likely N-glycine-N′-alanine. It is the first time that this molecule has been identified as a natural compound. Its exact role is unknown and remains to be elucidated. We suppose that its formation could play an important role in clam defense response by attenuating Ca2+ dependent cell death induced by TBT. Therefore this compound could be a promising biomarker for TBT exposure.

Chemical compounds studied in this article: Tributyltin chloride (PubChem, CID: 15096)

Keywords: Clam, Heart, Tributyltin, Metabolism, HRMAS NMR, Toxicity, N-glycine-N′-alanine

1. Introduction

Increasing antropogenic degradation of the costal environment has a negative effect on the quality and quantity of costal shellfish culture [1]. The presence of organotin compounds in marine and freshwater ecosystems has received the most attention in toxicological or related studies because of its environmental and health hazards [2]. TBT is the most toxic of the butyltin compounds and it was selected because it is a worldwide pollutant that exists widely in marine ecosystems [3]. It is a strong lipophilic substance which is used in large scale and particularly in marine antifouling paints [4]. However, this compound detected in aquatic organisms [40] poses a broad range of responses at different levels. Deleterious effects on these animals and the well-studied effects of TBT exposure were reproductive functions, endocrine and immune systems responses [5], [6]. The toxic effect of TBT led to reduce animal growth rate [7], decrease of fertility through ovarian disorganization or atrophy [42], reproduction failure [8] and alteration of sexual differentiation [9]. The main effect of TBT recorded around the world is a condition referred to as imposex, an endocrine disruption in molluscs that leads to masculinization of females for over 150 gasteropod species [41] even at very low concentrations of TBT (<1 ng/L) [10].

High concentrations of TBT have been detected in sediment near harbors, fishery ports, marinas, and shipyards [11]. Ports and marinas are recipients of a variety of toxic chemical inputs and can affect adjacent marine coastal ecosystems [12]. Due to the nautical activities, it was reported by Devier et al. [13] that mussels transplanted to oyster farms have revealed concentrations of approximately 30 μg kg−1 dry/wt, and showed increases in July and August, even if no trace of TBTs has been detected in the water. More worrying, in mussels transplanted to harbor areas, concentrations of 800–2400 μg kg−1 were recorded.

Due to its persistence for a long time in the environment and its severe impact on aquatic ecosystems, the International Maritime Organization has decided to prohibit uses of TBT in antifouling paints since 2003 [14] and total prohibition since 2008 [5]. Present and future restrictions will unfortunately not immediately remove TBT and its degradation products from the marine environment, since these compounds are retained in the sediments where they persist [5]. Indeed, butyltins can be released from marine sediments, taken up by filter feeders and bioconcentrated in animal tissues [15]. For example, Tsuda et al. [16] reported that the daily average intake of TBT by humans from market-bought seafood has been estimated to vary worldwide from 0.18 to 2.6 μg/person. As a consequence of the prohibition of TBT use, the levels of TBT have markedly decreased in seawater but a recent study has revealed that TBT concentrations found in tissues of Mytillus galloprovincialis and in fish are still high enough to cause chronic effects in sensitive species [17].

Bivalve molluscs are known to be reliable indicators of the marine environment, because of their high filtration rate, their widespread distribution and their ability to bioconcentrate many toxicants. Among these bivalves, the carpet-shell clam Ruditapes decussatus, is an important component of infaunal communities and is an economically important bivalve in many countries. This invertebrate was submitted in the last decade, to various anthropogenic pollutants [18]. Among them TBT has previously been shown to be a threat for the growth and development of R. decussatus larvae at environmentally relevant levels [19]. It was also reported that some juveniles exposed to TBT developed abnormal shell growth, laterally, changing the typical flattened shape of riorly [4]. Moreover, it was suggested that TBT exposure causes a potential masculinization of clam R. decussatus physiology as a consequence of an increase in tissue testosterone levels as well as an alteration of testosterone metabolism and a decrease in oestradiol levels [20].

The purpose of this work was to elucidate mechanisms involved in the toxicity of TBT after characterization of metabolic profile of heart tissue of clam R. decussatus exposed to this organotin. Mechanistic understanding at biochemical levels could increase the knowledge of the survival strategies of the organisms under stressed conditions and therefore may be useful in water quality biomonitoring to protect ecosystem health. This work was performed using HRMAS NMR spectroscopy method because in a previous study we had demonstrated its high applicability to elucidate the mechanism of Roundup® toxicity [21].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Tributyltin chloride (T50202, 96%), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and trimethylsilyl propionic acid (TSP) were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich. Deuterium oxide (D2O) 100% was purchased from Euriso-top. For experimentation, TBT was solubilized in DMSO and maximal concentration of solvent in this study was 5‰.

2.2. Clam exposure

Adult clams, R. decussatus, of 3–4 cm shell length, were collected from a local fish farm. After acclimatization in aerated seawater for three days, 30 clams were transferred to five tanks (n = 6 in each tank): one control, one DMSO and three exposed groups to TBT (10−9 M, 10−6 M and 10−4 M) during 24 h and 72 h. The experiment was carried out four times. After treatments, clams were immediately dissected and the hearts were removed for HRMAS NMR analyses.

2.3. Metabolite extraction

A total of 60 clam samples were used to metabolite extraction. Immediately after treatment, clam heart tissues were taken off (n = 12 for each condition tested), pooled than weighed and crushed in 400 μL of water. The homogenate was centrifuged (4 °C, 10 min, 13,000 × g) and the supernatant was removed and lyophilized prior to one dimensional 1D 1H NMR analyses. The experiment was carried out four times.

2.4. NMR spectroscopy

All the acquisitions were recorded on a BRUKER Avance III HD 500 spectrometer equipped with an indirect HRMAS 1H/31P probe. During the HRMAS study, one heart was loaded in a 4 mm ZrO2 cylindrical rotor with 70 μL of seawater/D2O 3/1, at a spinning rate of 5000 Hz, around an axis which is oriented at the so-called magic angle of 54.7° with regard to the magnetic field B0. The spectra were performed with a 30° pulse, a 2 s delay and a presaturation of the H2O signal. The temperature was controlled at 25 °C. The result was an NMR spectrum with resolution approaching that of a liquid sample which made it possible to analyze the metabolites of low molecular weight in solution inside the organisms.

For classical 1D 1H NMR, the lyophylized powders were dissolved in 0.7 mL of deuterium oxide. 1H NMR spectra were performed according to the method previously described [21]. Identification of some metabolites were confirmed by the COSY DQF (Double-quantum filtered 1H–1H correlated spectroscopy), HMQC 1H–13C (Heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence 1H–13C), HMBC 1H–13C (Heteronuclear multiple bond coherence 1H–13C), HMBC 1H–15N and DOSY (Diffusion ordered spectroscopy) sequences.

2.5. NMR quantification

The extract of 15 clam heart tissues was dissolved in 700 μL of D2O and placed in NMR tube. In order to evaluate the level of metabolites and compare the NMR profiles, 5 μL of TSP solution (50 mg/mL) was added to the NMR tubes. The spectra were performed with a 30° pulse and a 10 s delay. The temperature was controlled at 25 °C. The obtained spectra were properly phased, baseline corrected and manually integrated. Calculation of metabolite concentrations was based on integration of NMR peaks. Area of each metabolite peak was compared to that of TSP of known concentration. The ratio of areas, proportional to the number of protons, gave the concentration of each considered metabolite.

2.6. Data analysis and statistics

All values are expressed as the means ± standard deviations (SD). Statistical differences were determined by performing the student t-test after checking the normality of distribution. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of TBT exposure on the metabolism of heart clam tissue

The metabolic 1H HRMAS NMR profiles of treated groups showed differences in the spectral region between 4.5 and 0 ppm among the three groups of clam exposed to TBT (10−9, 10−6 and 10−4 M) and also when compared to control group (Fig. 1). However, no variation in major peaks was found between the control and the exposed groups in the part of the spectrum above 4.5 ppm and, the metabolic 1H NMR profiles of control was similar to DMSO treated controls (data not shown). Generally, our results show that alanine is accumulated even at short exposure times (24 h) to TBT. Surprisingly, the NMR spectra indicated also that highest concentrations of TBT (10−6 and 10−4 M) induced the accumulation of an unusual metabolite (metabolite 2). Indeed, we noticed the appearance of two very closed doublet (1.54 and 1.55 ppm) and a singlet (3.64 ppm). These signals seem to be present simultaneously and in the same proportions, which lets us think that they belong to the same molecule.

Fig. 1.

Representative 500 MHz 1H HRMAS–NMR spectra of carpet shell clam (Ruditapes decussatus) heart after 24 and 72 h TBT exposure (N = 12 for each concentration tested). Keys: alanine (1), unknown compound (2), pyruvate (3), glutamate (4), succinate (5) and hypotaurine (6).

After 72 h of treatment, the obvious modifications in the proton spectra from heart tissues of clam exposed to TBT (10−6 and 10−4 M) were the increase in the level of alanine, succinate and that of the unknown metabolite 2, which is relatively more abundant than after 24 h of treatment. However, in low dose (10−9 M) TBT treated groups, the metabolite 2 is less accumulated but levels of alanine and succinate increased.

3.2. Metabolite analysis of clam heart extracts

1H NMR spectra of clam heart extracts from control and TBT exposures (10−9, 10−6 and 10−4 M) are presented in Fig. 2. They show 18 assigned metabolites which belong to amino acids (e.g. valine, leucine, isoleucine, glycine, arginine, etc.), organic osmolytes (taurine, betaine, hypotaurine and homarine) and Krebs cycle intermediates such as succinate (Table 1). The most prevalent compounds in clam heart tissues were betaine (3.28 and 3.92 ppm), taurine (3.27 and 3.44 ppm) and glycine (3.57 ppm) as we have indicated in our previous study [21].

Fig. 2.

Representative one dimensional 500 MHz 1H NMR spectra of clam heart tissue extracts from control and TBT (10−9, 10−6, 10−4 M) exposures (N = 48 for each group of clam). Keys: Alanine (1), unknown metabolite (2), pyruvate (3), glutamate (4), succinate (5), hypotaurine (6), isoleucine (7), leucine (8), valine (9), lactate (10), arginine (11), taurine (12), betaine (13), glycine (14), homarine (15), β-glucose (16), α-glucose (17), glycogen (18).

Table 1.

Chemical shifts of metabolites identified in 1H NMR spectrum of heart tissue extracts (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quadruplet, dd = double doublet, m = multiplet).

| Metabolites | Chemical shift and peak shape | Peak identification in Fig. 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Amino acids | ||

| Isoleucine | 0.93 (t) 0.99 (d) | 7 |

| Leucine | 0.95 (d) 0.96 (d) | 8 |

| Valine | 1.00 (d) 1.05 (d) | 9 |

| Alanine | 1.49 (d) | 1 |

| Arginine | 1.70 (m) 1.93 (m) | 11 |

| Glutamate | 2.04 (m) 2.11 (m) 2.37 (m) | 4 |

| Organic acids | ||

| Lactate | 1.34 (d) | 10 |

| Energy related | ||

| α-Glucose | 5.22 (d) | 17 |

| β-Glucose | 4.66 (d) | 16 |

| Glycogen | 5.40 (br s) | 18 |

| Pyruvate | 2.28 (s) | 3 |

| Organic osmolytes | ||

| Betaine | 3.28 (s) 3.92 (s) | 13 |

| Glycine | 3.57 (s) | 14 |

| Hypotaurine | 2.66 (t) 3.36 (t) | 6 |

| Taurine | 3.27 (t) 3.44 (t) | 12 |

| Homarine | 4.38 (s) 7.99 (dd) 8.05 (d) 8.56 (dd) 8.72 (d) | 15 |

| Krebs cycle intermediate | ||

| Succinate | 2.43 (s) | 5 |

| N-glycine-N′-alanine | 1.54 (d) 1.55(d) 3.63 (s) 3.64 (s) | 2 |

In clam R. decussatus exposed to different doses of TBT for 72 h, the concentrations of main metabolites: amino acids (alanine, metabolite 2), tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates (succinate) and organic osmolytes (betaïne, taurine and glycine) were quantified using a TSP solution (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimated concentrations of metabolites in heart tissues of clams determined after NMR peak integration. Values are mean ± SEM. Significant differences in metabolite levels between the TBT treated groups and the control groups are indicated with asterisks (**p < 0.01; * p < 0.05; NS: no significant).

| Metabolite concentrations (μmol/g wet/wt) | Control | TBT 10−9 M | TBT 10−6 M | TBT 10−4 M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine | 10.97 ± 3.32 | 15.07 ± 1.71** | 25.14 ± 5.07** | 16.17 ± 5.18* |

| N-Gly-N′-Ala | 3.96 ± 2.77 | 7.46 ± 3.77** | 17.63 ± 1.96** | 14.38 ± 1.01** |

| Succinate | 2.32 ± 1.61 | 4.04 ± 1.45** | 4.50 ± 1.95** | 7.41 ± 0.67** |

| Taurine | 110.73 ± 11.31 | 116.12 ± 17.44 NS | 71.12 ± 9.32** | 115.32 ± 5.35* |

| Betaine | 112.51 ± 11.10 | 114.26 ± 14.76 NS | 78.60 ± 6.66** | 123.86 ± 5.71* |

| Glycine | 44.14 ± 0.23 | 32.49 ± 3.80** | 18.44 ± 0.33** | 23.26 ± 5.39** |

Results show that TBT induced alteration of organic osmolytes and this was not dose dependent. Taurine and betaine were not significantly affected (p > 0.05) in groups treated with TBT 10−9 M with respect to the control clam. However, in clam groups exposed to TBT 10−6 M, levels of those molecules showed a significant depletion (p < 0.01) in comparison to that detected in the control groups and were respectively 71.12 ± 9.32 and 78.6 ± 6.66 μmol/g wet/wt. By contrast to 10−6 M, the highest dose of TBT (10−4 M) induced a significant increase (p < 0.05) in the amount of those metabolites.

Treatment with TBT also led to a significant depletion of glycine in all clam groups (p < 0.01). The minimum was about half of the concentration determined in control group and was detected in clams treated with TBT 10−6 M. Moreover, results show that the highest levels of alanine and metabolite 2 were detected in clam groups exposed to TBT 10−6 M (respectively 25.14 ± 5.07 and 17.63 ± 1.96 μmol/g wet/wt; p < 0.01), whereas the maximum of succinate was obtained with TBT 10−4 M (7.41 ± 0.67 μmol/g wet/wt; p < 0.01).

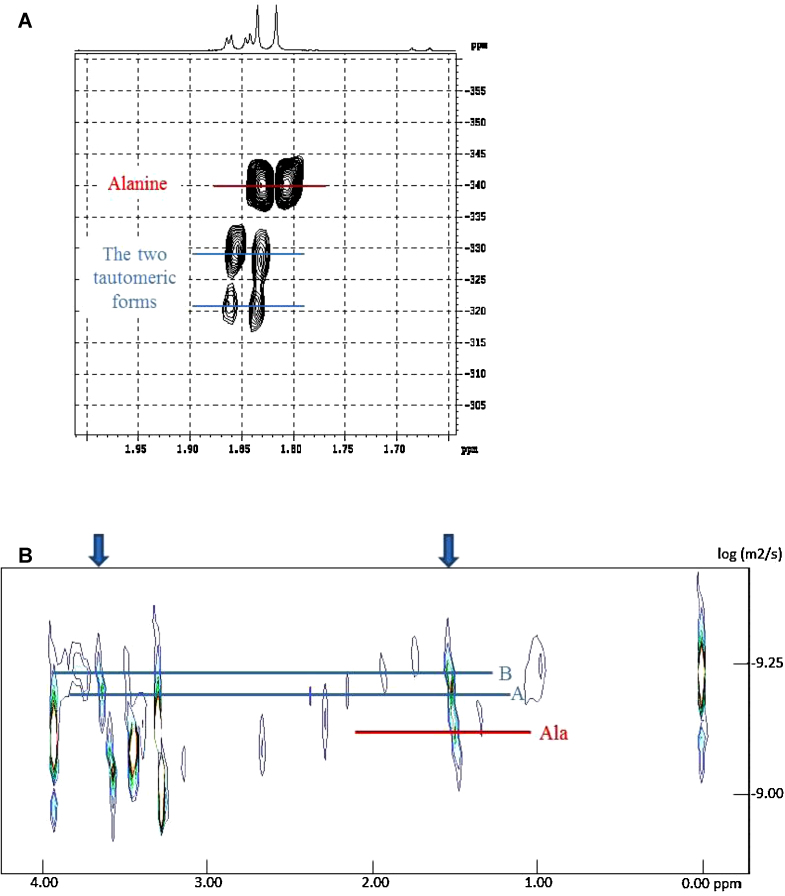

3.3. Analysis of the unknown metabolite 2

In order to characterize the new compound, heart tissue extracts from clams exposed for 72 h to TBT 10−6 M were analyzed using 2D NMR. Results show that the appearing doublets at 1.54 and 1.55 ppm belong to alanine derivative substituted on the nitrogen. In the same way, the singlets at 3.63 and 3.64 ppm belong to glycine derivative substituted on the nitrogen (Table 1). According to these results, the new molecule might be the N-glycine-N′-alanine under the shape of a tautomeric equilibrium (Fig. 3A). With a view to confirm our hypothesis, further experiments were performed. Best detection of the two tautomers was obtained after registering a spectrum of this extract in MeOD at −10 °C (Fig. 3B). Integration of these signals showed that there is 59% of the majority derivative A and 41% of the other B as previously reported in the literature [22]. Indeed, when they synthesized the N-glycine-N′-Alanine, the same ratio of tautomers were obtained. Then, the HMBC 1H/15N analysis of this sample confirmed that the two CH3 of tautomers have neighboring nitrogen with chemical shifts appreciably different which are −329 ppm for A and −321 ppm for B (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 3.

(A) N-glycine-N′-alanine tautomeric equilibrium. (B) Part of a 500 MHz 1H NMR spectrum of clam heart tissue extract from TBT 10−6 M after 72 h exposure: the extract has been solved in MeOD and the spectrum was recorded at -10 °C with a 10 s delay.

Fig. 4.

(A) Part of a 500 MHz HMBC 1H/15N spectrum of clam heart tissue extract from TBT 10−6 M after 72 h exposure: the extract has been solved in MeOD and the spectrum was recorded at 25 °C. Nitromethane is used as reference for 15N chemical shifts. (B) Part of a 500 MHz DOSY spectrum of clam heart tissue extract from TBT 10−6 M after 72 h exposure: the lyophilized extract has been solved in D2O and the spectrum was recorded at 25 °C.

Moreover, a DOSY NMR analysis confirmed that the doublet at 1.54 ppm and the singlet at 3.63 ppm belong to the same molecule (tautomer A) whereas, the doublet at 1.55 ppm and the singlet at 3.64 ppm belong to another molecule (tautomer B) (Fig. 4B). All those experiments tend to prove that compound 2 is the N-glycine-N′-alanine but its isolation is required to confirm its structure.

4. Discussion

Metabolic profiling can provide an overview of the metabolic status of a biological system including, cells, tissues, organs or even whole organisms [23]. Metabolism is context dependent and metabolite levels change with the physiological, developmental, or pathological state of cells, tissues, organs or organisms [23].

The original NMR spectrum of heart tissue of clam R. decussatus was dominated by organic osmolytes (betaine and taurine) as previously reported for clam Ruditapes philippinarum [24], [25]. As indicated in the literature, these molecules play an important role in osmoregulation in marine organisms via various metabolic pathways and hence were detected at higher level than other metabolites [26]. Those small organic molecules can actively accumulate in high environment salinity and released when the salinity decreases.

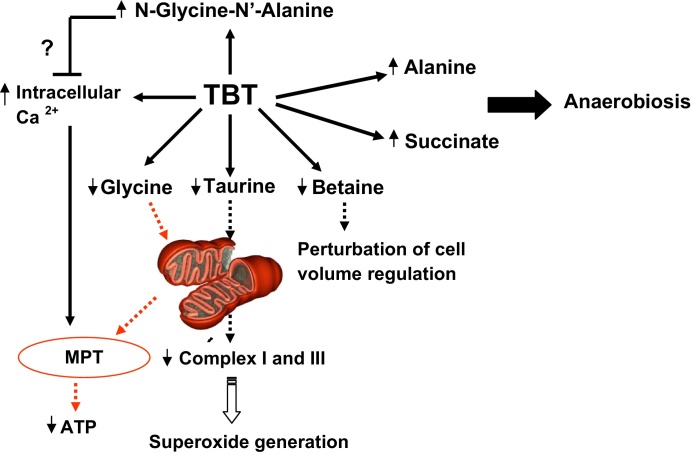

The present study showed that, in clams exposed to TBT 10−9 M level of taurine was not significantly affected. By contrast, TBT at 10−6 M induced a significant decrease in the level of this metabolite. It was reported that taurine depletion is associated with cardiomyopathy [27], [28]. Its deficiency leads to impaired electron transport in cardiomyocytes, which in turn increases mitochondrial superoxide generation by depressing the activities of primary mitochondrial sources of superoxide generation complex I and III [29]. This can partly explain the mortality observed when clams were exposed to this dose. Unlike TBT 10−6 M, no mortality was observed in clam exposed to the highest dose of TBT and results showed that this dose induced a significant increase in the level of taurine in comparison with control group. It was indicated that increasing taurine levels restores respiratory chain activity and increases the synthesis of ATP at the expense of superoxide anion production [27]. This indicates that the mechanism of TBT toxicity is not dose-dependent and this organotin may affect different pathways depending on the used dose. Thus, we can suggest that taurine plays a cytoprotective role by maintaining the normal contractile function and by preventing mitochondrial superoxide production.

According to our results, betaine level was also affected in clam groups exposed to TBT and this in the same trend as that of taurine. Betaine is essential for cell volume regulation and is a major source of methyl groups for the methylation process that are essential for diverse functions such as creatine phosphate and phospholipid biosynthesis and epigenic control of gene expression [30]. Previous studies indicated that protective effect of betaine against isoprenaline-induced myocardial dysfunction in rats was attributed to its ability to strengthen the myocardial membrane by its membrane stabilizing action or to a counteraction of free radicals by its antioxidant property [31]. Therefore a betaine insufficiency may itself be pathogenic [30]. Thus, we can suggest that betaine deficiency contribute in TBT toxicity whereas its increase in tissue could play a protective effect against TBT damage.

Concerning groups treated with the lowest dose of TBT, our results showed that this organotin at 10−9 M did not affect the levels of betaine and taurine suggesting that this dose is not high enough to induce disturbance in the amount of those metabolites under short time exposure.

The results of the present study also showed a pronounced depletion in the level of glycine in all clam groups exposed to TBT but this decrease was less important in clams exposed to low concentration of this organotin. A depletion of glycine was also reported in mussel exposed to Cu and Cd [43]. Several studies proved that glycine is a cytoprotective amino acid acting as an inhibitor of mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) [44] (Fig. 5). Glycine receptors are expressed in cardiomyocytes and participate in cytoprotection from hypoxia/reoxygenation injury [32]. Moreover, it was reported that glycine is beneficial to myocardial preservation by improving cardiomyocyte energy metabolism and increasing ATP abundance [33]. Thus, the decrease in glycine after treatment with TBT is probably due to the fact that glycine is involved in the regeneration of ATP to maintain energy metabolism in a level required for survival. This depletion also partly explains the mortality observed in clam exposed to TBT 10−6 M.

Fig. 5.

Effect of TBT in heart clam Ruditapes decussatus: Possible mechanisms.

Generally, our results show that alanine is accumulated even at short exposure times (24 h) to TBT. In this study, accumulation of alanine and succinate was observed after 24 h only with TBT 10−4 M and after 72 h of exposure with all concentration of TBT tested. Alanine is a free amino acid and is considered as an important organic osmolyte found in invertebrates. Recent studies have reported that some marine mollusks use high intracellular levels of free amino acids to protect themselves against the high and fluctuating extracellular osmolarity of their environment, and these pools of oxidizable amino acids are also used extensively in cellular energy metabolism [34]. In some studies on marine organisms, the increase of alanine caused by anoxia was correlated with the increase of succinate during environmental anoxia [35]. According to our results, a similar phenomenon regarding the levels of alanine and succinate was observed in clam exposed to TBT particularly with the highest concentration of this organotin. The increase in succinate was also reported by Zhou et al. [3] for abalone after exposure to TBT who suggested the occurrence of anaerobic respiration and slowing of the TCA cycle and the electron transport chain. Accumulation of this metabolite was more important with TBT 10−4 M and this was in agree with our observation indicating that clam shells remain closed when this bivalve is exposed to the highest concentration of TBT. It is generally thought that bivalves with opened valves rely on an aerobic metabolism but after closing the valves the enclosed oxygen is spent within a few minutes and environmental anaerobiosis commences [36].

Moreover, these results show important variations of the level of another original metabolite likely N-glycine-N′-alanine.

Indeed, the level of N-glycine-N′-alanine increased with all concentration of TBT and the highest level is observed with TBT 10−6 M. To our knowledge, this metabolite has not been identified as a natural compound but has been previously synthesized and analyzed by NMR both in solution and in the solid state [22]. This compound exists as zwitterion with the ammonium group proximal to the carboxylate anion. A consequence of zwitterion formation is the presence of large regions with distinctly negative electrostatic potentials of which the latter surrounds the carboxylate group. The exact role of this metabolite is unknown and remains to be elucidated. We suggest that its formation could play an important role in clam defense response against TBT toxicity. Corsini et al. [37] indicated that the earlier event triggered by TBT treatment is an increase in intracellular Ca2+. Also, results obtained with cultured clam heart cells exposed to TBT 10−6 M showed a significant increase of L-type calcium currents after 30 min of exposure [38]. Blockage of the Ca2+ channel opening or chelation of cytosolic Ca2+ is effective enough to protect TBT from inducing cell death [39]. Thus, we suggest that N-glycine-N′-alanine bind to calcium cations and may partly attenuate Ca2+ dependent cell death induced by TBT. Therefore this compound may be useful in assessment of TBT pollution. Further research would be required for the validation of these endpoints.

5. Conclusion

In this study the metabolic responses in heart tissues of clam R. decussatus exposed to TBT were investigated using NMR. From all our results, the mechanisms involved in the response to exposure to this organotin depend on the concentrations used. The toxicological effects of TBT lead to the disturbance of organic osmolytes (taurine, betaine and glycine) but also of metabolites related to anaerobiois (alanine and succinate). Moreover, the main finding of this study was the identification of a new biomarker to TBT pollution, likely N-glycine-N′-alanine according to this preliminary study. Its role remains unclear but we suggest that this metabolite could play an important role in clam protection against the deleterious effect of TBT. The success of this preliminary study suggests future studies such as isolation of the new metabolite in order to confirm its structure and to elucidate its precise role in TBT toxicity. These results demonstrate the high applicability of NMR techniques to elucidate mechanisms of TBT toxicity (Fig. 5) but also to identify and characterize new biomarkers which may be useful in designing tests aimed at assessing stress under field conditions.

Transparency document

.

Footnotes

Available online 2 October 2014

References

- 1.Chinabut S., Somsiri T., Limsuwan C., Lewis S. Problems associated with shellfish farming. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2006;25:627–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizuhashi S., Ikegaya Y., Matsuki N. Cytotoxicity of tributyltin in rat hippocampal slice cultures. Neurosci. Res. 2000;38:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou J., Zhu X.S., Cai Z.H. Tributyltin toxicity in abalone (Haliotis diversicolor supertexta) assessed by antioxidant enzyme activity, metabolic response, and histopathology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;183:428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coelho M.R., Langston W.J., Bebianno M.J. Effect of TBT on Ruditapes decussatus juveniles. Chemosphere. 2006;63:1499–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antizar-Ladislao B. Environmental levels, toxicity and human exposure to tributyltin (TBT)-contaminated marine environment. a review. Environ. Int. 2008;34:292–308. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonak S., Pangam P., Giriyan A., Hawaldar K. Implications of the ban on organotins for protection of global coastal and marine ecology. J. Environ. Manage. 2009;90(Suppl. 1):S96–S108. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park K., Kim R., Park J.J., Shin H.C., Lee J.S., Cho H.S., Lee Y.G., Kim J., Kwak I.S. Ecotoxicological evaluation of tributyltin toxicity to the equilateral venus clam Gomphina veneriformis (Bivalvia: Veneridae) Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 2012;32:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue S., Oshima Y., Nagai K., Yamamoto T., Go J., Kai N., Honjo T. Effect of maternal exposure to tributyltin on reproduction of the pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata martensii) Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2004;23:1276–1281. doi: 10.1897/03-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lima D., Reis-Henriques M.A., Silva R., Santos A.I., Castro L.F., Santos M.M. Tributyltin-induced imposex in marine gastropods involves tissue-specific modulation of the retinoid X receptor. Aquat. Toxicol. 2011;101:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alzieu C. Environmental impact of TBT: the French experience. Sci. Total. Environ. 2000;258:99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(00)00510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim N.S., Shim W.J., Yim U.H., Ha S.Y., An J.G., Shin K.H. Three decades of TBT contamination in sediments around a large scale shipyard. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011;192:634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.deMora S.J., Stewart C., Phillips D. Sources and rate of degradation of tri(nbutyl)tin in marine sediments near Auckland. N. Z. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1995;30:50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devier M.H., Augagneur S., Budzinski H., Le Menach K., Mora P., Narbonne J.F., Garrigues P. One-year monitoring survey of organic compounds (PAHs, PCBs, TBT), heavy metals and biomarkers in blue mussels from the Arcachon bay, France. J. Environ. Monit. 2005;7:224–240. doi: 10.1039/b409577d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Wezel A.P., van Vlaardingen P. Environmental risk limits for antifouling substances. Aquat. Toxicol. 2004;66:427–444. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyer I.J. Toxicity of dibutyltin, tributyltin and other organotin compounds to humans and experimental animals. Toxicology. 1999;55:253–298. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(89)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuda T., Inoue T., Kojima M., Aoki S. Daily intakes of tributyltin and triphenyltin compounds from meals. J. AOAC Int. 1995;78:941–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kucuksezgin F., Aydin-Onen S., Gonul L.T., Pazi I., Kocak F. Assessment of organotin (butyltin species) contamination in marine biota from the Eastern Aegean sea. Turkey Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011;62:1984–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bebianno M.J., Geret F., Hoarau P., Serafim M.A., Coelho M.R., Gnassia-Barelli M., Romeo M. Biomarkers in Ruditapes decussatus: a potential bioindicator species. Biomarkers. 2004;9:305–330. doi: 10.1080/13547500400017820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coelho M.R., Fuentes S., Bebianno M.J. TBT effects on the larvae of Ruditapes decussatus. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK. 2001;81:259–265. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morcillo Y., Porte C. Evidence of endocrine disruption in clams – Ruditapes decussata – transplanted to a tributyltin-polluted environment. Environ. Pollut. 2000;107:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(99)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanana H., Simon G., Kervarec N., Mohammadou B.A., Cerantola S. HRMAS NMR as a tool to study metabolic responses in heart clam Ruditapes decussatus exposed to Roundup®. Talanta. 2012;97:425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ballano G., Jimenez A.I., Cativiela C., Claramunt R.M., Sanz D., Alkorta I., Elguero J. Structure of N, N′-bis(amino acids) in the solid state and in solution. A 13C and 15N CPMAS NMR study. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:8575–8578. doi: 10.1021/jo801362q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin C.Y., Viant M.R., Tjeerdema R.S. Metabolomics: methodologies and applications in the environmental sciences. J. Pestic. Sci. 2006;31:245–251. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L., Liu X., You L., Zhou D., Wang Q., Li F. Benzo(a)pyrene-induced metabolic responses in Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) based metabolomics. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2011;32:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L., Liu X., You L., Zhou D., Wu H., Li L., Zhao J., Feng J., Yu J. Metabolic responses in gills of Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum exposed to copper using NMR-based metabolomics. Mar. Environ. Res. 2011;72:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preston R.L. Transport of amino acids by marine invertebrates. Comp. Physiol. Biochem. 2005;265:410–421. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ripps H., Shen W. Review: taurine: a “very essential” amino acid. Mol. Vis. 2012;18:2673–2686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaffer S.W., Jong C.J., Ramila K.C., Azuma J. Physiological roles of taurine in heart and muscle. J. Biomed. Sci. 2010;1(Suppl. 17):S2. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-17-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jong C.J., Azuma J., Schaffer S. Mechanism underlying the antioxidant activity of taurine: prevention of mitochondrial oxidant production. Amino Acids. 2012;42:2223–2232. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0962-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lever M., George P.M., Elmslie J.L., Atkinson W., Slow S., Molyneux S.L., Troughton R.W., Richards A.M., Frampton C.M., Chambers S.T. Betaine and secondary events in an acute coronary syndrome cohort. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganesan B., Buddhan S., Anandan R., Sivakumar R., AnbinEzhilan R. Antioxydant defense of betaine against isoprenaline-induced myocardial infraction in rats. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2010;37:1319–1327. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi R.B., Zhang J.Y., Lu D.X., Wang H.D., Wang H.H., Li C.J. Glycine receptors contribute to cytoprotection of glycine in myocardial cells. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2007;120:915–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y., Lv S.J., Yan H., Wang L., Liang G.P., Wan Q.X., Peng X. Effects of glycine supplementation on myocardial damage and cardiac function after severe burn. Burns. 2013;39:729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viant M.R., Rosenblum E.S., Tjeederma R.S. NMR-based metabolomics: a powerful approach for characterizing the effects of environmental stressors on organism health. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003;37:4982–4989. doi: 10.1021/es034281x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santini G., Bruschini C., Pazzagli L., Pieraccini G., Moneti G., Chelazzi G. Metabolic responses of the limpet Patella caerulea (L.) to anoxia and dehydration. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001;130:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ortmann C., Grieshaber M.K. Energy metabolism and valve closure behaviour in the Asian clam Corbicula fluminea. J. Exp. Biol. 2003;206:4167–4178. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corsini E., Viviani B., Marinovich M., Galli C.L. Role of mitochondria and calcium ions in tributyltin-induced gene regulatory pathways. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1997;145:74–81. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.8100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanana H., Talarmin H., Pennec J.P., Droguet M., Gobin E., Marcorelle P., Dorange G. Establishment of functional primary cultures of heart cells from the clam Ruditapes decussatus. Cytotechnology. 2011;63:295–305. doi: 10.1007/s10616-011-9347-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unno T., Iida R., Okawa M., Matsuyama H., Hossain M.M., Kobayashi H., Komori S. Tributyltin-induced Ca(2+) mobilization via L-type voltage-dependent Ca(2 + ) channels in PC12 cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009;28:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abidli S., Lahbib Y., Trigui El Menif N. Imposex and butyltin concentrations in Bolinus brandaris (Gastropoda: Muricidae) from the northern Tunisian coast. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011;177:375–384. doi: 10.1007/s10661-010-1640-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakanishi T. Endocrine disruption induced by organotin compounds; organotins function as a powerful agonist for nuclear receptors rather than an aromatase inhibitor. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;33:269–276. doi: 10.2131/jts.33.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sant’Anna B.S., Santos D.M., Marchi M.R., Zara F.J., Turra A. Effects of tributyltin exposure in hermit crabs: Clibanarius vittatus as a model. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2012;31:632–638. doi: 10.1002/etc.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu H., Wang W.X. NMR-based metabolomic studies on the toxicological effects of cadmium and copper on green mussels Perna viridis. Aquat. Toxicol. 2010;100:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruiz-Meana M., Pina P., Garcia-Dorado D., Rodriguez-Sinovas A., Barba I., Miro-Casas E., Mirabet M., Soler-Soler J. Glycine protects cardiomyocytes against lethal reoxygenation injury by inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition. J. Physiol. 2004;558:873–882. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

.