To the Editors

The recent publication of Wohl et al. describes a randomized controlled trial of the imPACT intervention, which had the laudable aim of preventing loss of HIV viral suppression in persons leaving prison by facilitating care access after release 1. The objectives of the imPACT intervention are important, as engagement of vulnerable persons in care will be key to lowering community viral load. Nonetheless, we question the authors’ characterization that their comprehensive motivational intervention to prevent loss of HIV viral suppression failed. The investigators dropped from analysis the experiences of participants who were reincarcerated, 16.5% (63/381) of all subjects. We believe this exclusion does not replicate real-world trajectories of persons with histories of incarceration, and could skew the results of the study.

We strongly agree that, among those not reincarcerated, the large proportion of participants who experienced an increase in viral load following community re-entry in both study arms was disappointing with respect to public health goals. Prevention of transmission, via continued viral suppression post-release, is critical to treatment as prevention efforts in the community. We believe, however, that the exclusion of participants who were reincarcerated during the course of the study unfairly links maintenance of viral suppression with overcoming socio-structural barriers to staying out of jail or prison. Our primary question concerns the viremia outcomes in those reincarcerated, who comprised half of those dropped from analysis for study non-completion (63/125).

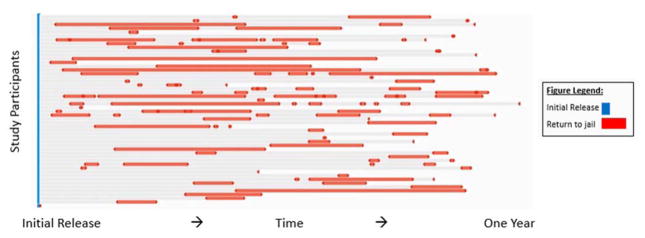

Given that presence in the community is necessary for engagement in care at a community site – a theoretical mediator of maintaining viral suppression – we understand how exclusion of those behind bars would seem logical at first glance. We argue, however, that this methodology mixes criminal justice outcomes and medical outcomes. Recidivism is common among persons living with HIV (PLWH) following release from corrections. Our experiences following a cohort of 89 HIV-infected persons upon release from jail in Atlanta, GA showed that 56.2% returned to a correctional setting at least once in the year following release (Figure 1). Furthermore, members in our cohort returned to jail up to 8 times in the year following initial release, and spent between none and 91% of their time back in jail (mean: 14.8%) 2. Medical care, including HIV care, while incarcerated is a constitutionally guaranteed right 3. Thus, jail could be an unfortunate but stable medical home for some persons, even after an initial release.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of SUCCESS Study Participants following initial Jail Release, Atlanta, GA (N = 89)

SUCCESS: Sustained, Unbroken Connection to Care, Entry Services, and Suppression

*N = 39 did not return to an Atlanta-area jail following release.

An earlier study of predictors of reincarceration among PLWH released from the Texas prison system found that ART use was statistically significantly associated with decreased risk of reincarceration. In contrast, male sex, African American race, psychiatric disorder, and release on parole were statistically significantly associated with increased risk of reincarceration 4. While imPACT study participants were presumably on ART at the time of their release, baseline characteristics also show that they were majority male, majority Black, had histories of substance use, and a third had high or very high psychological distress. We assume, but cannot confirm, whether those dropped from the study match these characteristics. These characteristics indicate a non-trivial risk of reincarceration among imPACT participants regardless of their receipt of an intervention with medically-aimed outcome objectives.

We advocate disentangling failure to attain a criminal justice objective from failure to reach a medical goal. Efforts should be made to continue delivery of interventions aimed at care engagement regardless of current residence (jail or non-jail) of study participants. Real strides in reducing recidivism come not from medical interventions, but prison programs such as adult basic, secondary and post-secondary education, which a recent meta-analysis shows reduce recidivism up to 43% 5 . We believe that periods of reincarceration should not be considered study failures if the primary outcome of the study is successful management of disease, not prevention of reincarceration. While not ideal, returns to a correctional facility remain a critical juncture to facilitate reengagement 6. Assessment of viral outcomes stratified by reincarceration may provide insight into potential interaction effects, and allow for inclusion of participants regardless of residence. We hope that in the future, single or multiple returns to correctional facilities do not preclude inclusion in data analysis, even if less rigid exclusion criteria make analysis more complicated.

Overall, the imPACT study provides insights into the challenges of engagement and maintenance of suppression by emphasizing the real-world socio-structural barriers that face PLWH released from incarceration. We agree with the study’s authors that their results “imply a need for interventions that directly address the chaotic social environments to which former inmates return…that act as obstacles to desired outcomes such as long-lasting suppression of HIV.” Indeed, social and structural resources, such as changing policies and policing, are needed beyond facilitation of linkage to community care to simultaneously prevent loss of viral suppression and recidivism. Determining factors that promote HIV suppression following incarceration may be the first step. Attempting to address all challenges at once may leave all unsolved.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: National Institute of Drug Abuse/National Institutes of Health Grant #: DA035728; Gilead Sciences

Footnotes

This data has not been presented in any publications.

References

- 1.Wohl DA, Golin CE, Knight K, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Intervention to Maintain Suppression of HIV Viremia Following Prison Release: The imPACT Trial. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2017 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spaulding AC, Drobeniuc A, Frew P, et al. SUCCESS: Illustrating Trends of Improved Retention in HIV Care after Jail Release. 10th Academic and Health Policy Conference on Correctional Health; March 17, 2017; Atlanta, GA. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estelle v. Gamble, 429 97(Supreme Court 1976).

- 4.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Harzke AJ, et al. Predictors of reincarceration and disease progression among released HIV-infected inmates. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(6):389–394. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis LM, Bozick R, Steele JL, Saunders J, Miles JNV. How Effective is Correctional Education? The Results of a Meta-Analysis. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2013. [Accessed 31 March 2017]. Available: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR200/RR266/RAND_RR266.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westergaard RP, Spaulding AC, Flanigan TP. HIV among persons incarcerated in the US: a review of evolving concepts in testing, treatment and linkage to community care. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2013;26(1):10. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835c1dd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]