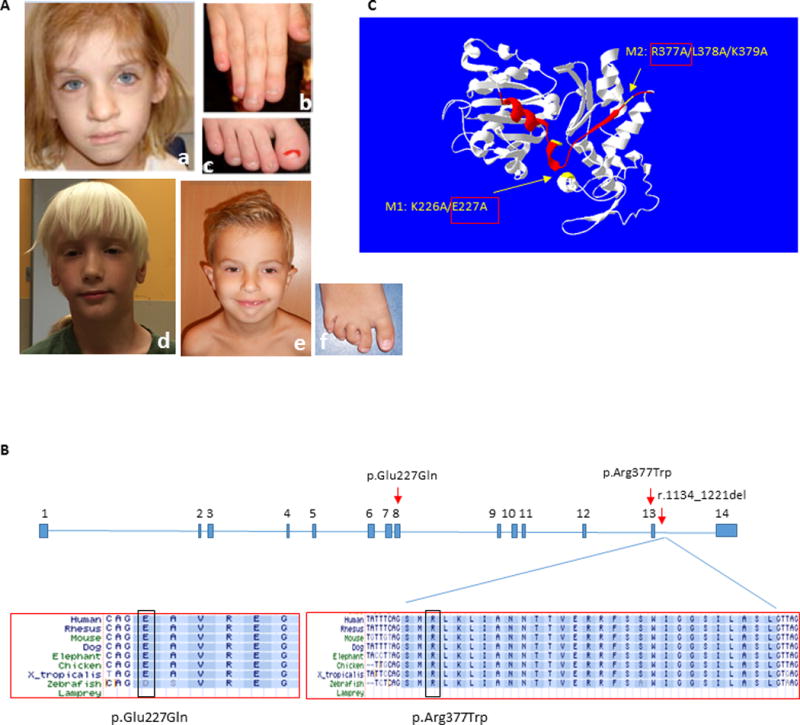

Figure 1. Clinical photographs of subjects and summary of ACTL6A pathogenic variants.

(A) Subject 1 at age 7 years, demonstrating coarse facial features with broad nasal tip (a), broad fingers and toes with dystrophic nails, and short distal phalanges (b, c); Subject 2 at age 6 years, demonstrating elongated face with large forehead, narrow eyelids, broad nasal tip and poorly developed philtrum ridge (d); and Subject 3 at age 6 years, showing prominent high forehead, low set everted ears, narrow eyelids, broad nasal tip, and small chin (e). Note digital anomalies, including overriding second toe, clinodactyly of 3rd–5th toes and sandal gap (f). The photographs of Subject 1 were reproduced with permission from the American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A (Brautbar, et al., 2009).

(B) Annotation of the two amino acid residues in exons 8 and 13 affected in Subjects 1 and 2, and the splicing variant causing in-frame deletion of exon 13 in Subject 3. Conservation across species is shown for the three variants.

(C) ACTL6A protein structure model as predicted by I-TASSER server (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER) (Zhang, 2008) and visualized using Swiss-Pdb viewer (http://spdbv.vital-it.ch/) (Guex and Peitsch, 1997), showing localization of the mutated amino acids in Subjects 1 and 2 (yellow arrows), and the deleted exon 13 in Subject 3 (red ribbon). Previous study (Nishimoto, et al., 2012) demonstrated that M1 and M2 mutants of human ACTL6A exhibit impaired binding capacity to beta actin (ACTB) and BRG1/SMARCA4, and thus disrupt ACTL6A recruitment to the BAF complex. This data supports a deleterious effect for p.Glu227Gln (E227Q/M1) and p.Arg377Trp (R377W/M2) on ACTL6A protein function.