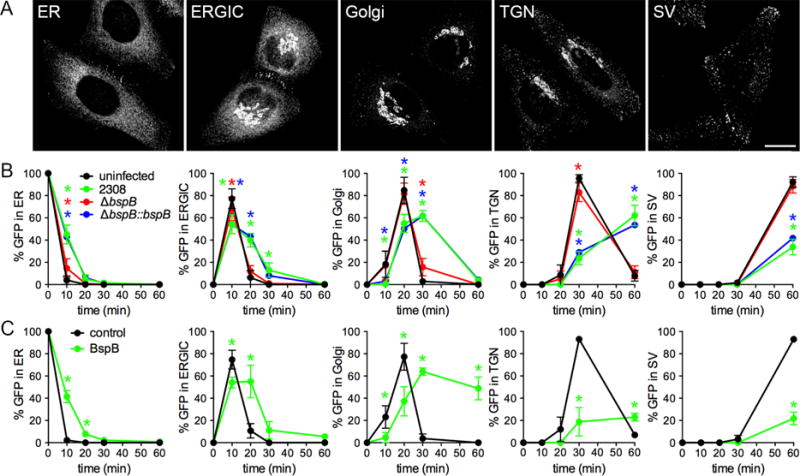

Figure 2. BspB impairs ER-to-Golgi secretory trafficking.

(A) Representative micrographs of ss-eGFP-FKBPF36M trafficking through secretory compartments [ER, ERGIC, Golgi, TGN, and post TGN secretory vesicles (SV)] in uninfected HeLa-M-(C1) cells post-rapamycin addition. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(B) Quantification of ss-eGFP-FKBPF36M trafficking in uninfected or Brucella-infected cells post-rapamycin addition over time. HeLa-M-(C1) cells were either uninfected or infected with B. abortus wild type (2308), ΔbspB, or complemented (ΔbspBⵆbspB) bacteria for 24 h. Rapamycin was added to initiate secretory traffic of ss-eGFP-FKBPF36M (t) and 0 its colocalization with Calnexin (ER), ERGIC-53 (ERGIC), GM130 (Golgi), p230 (TGN), or secretory vesicles was scored over a 60 min time course. Data are means ± SD from 3 independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significant differences compared to uninfected cells as determined by a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (P<0.05).

(C) Quantification of ss-eGFP-FKBPF36M trafficking in HeLa-M-(C1) cells transfected for 24 h with pCMV-HA (control) or pCMV-HA-BspB (BspB) prior to rapamycin addition. Data are means ± SD from 3 independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significant differences compared to control cells as determined by a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test (P<0.05).