Abstract

Nod 1 and 2 proteins play important roles in the innate immune response to pathogenic microbes, but mounting data suggest these pattern recognition receptors might also play key roles in adaptive immune responses. Targeting Nod1 and Nod2 signaling pathways in T cells is likely to provide a new strategy to modify inflammation in a variety of disease states, particularly those that depend on antigen-induced T cell activation. To better understand how Nod1 and Nod2 proteins contribute to adaptive immunity, this study investigated their role in alloantigen-induced T cell activation and asked whether their absence might impact in vivo alloresponses using a severe acute graft versus host disease model.

The study provided several important observations. We found that the simultaneous absence of Nod1 and Nod2 primed T cells for activation-induced cell death. T cells from Nod1x2-/- mice rapidly underwent cell death upon exposure to alloantigen. The Nod1x2-/- T cells had sustained p53 expression that was associated with downregulation of its negative regulator MDM2. In vivo, mice transplanted with an inoculum containing Nod1x2-/- T cells were protected from severe GVHD.

The results show that the simultaneous absence of Nod1 and Nod2 is associated with accelerated T cell death upon alloantigen encounter, suggesting these proteins might provide new targets to ameliorate T cell responses in a variety of inflammatory states, including those associated with bone marrow or solid organ transplantation.

Introduction

The innate immune system provides rapid defense responses to pathogens and products of tissue injury. This primitive defense system recognizes conserved structures of molecules released from microbes and dead and dying cells that bind to membrane-bound and cytosolic pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Two well-characterized intracytosolic PRRs are the nucleotide-binding and oligomerization-domain containing (Nod) proteins Nod1 and Nod2, which are members of the Nod-like receptor (NLR) family of PRRs. These proteins sense peptidoglycan fragments of bacterial cell walls and activate intracellular signaling pathways that drive proinflammatory and antimicrobial responses. Over the past decade substantial data have emerged defining key roles for Nod family members in chronic human diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, familial arthritis/uveitis syndromes and early onset sarcoidosis (1).

Nod proteins are well known to participate in the innate immune response against bacterial pathogens, but mounting data also support a role for Nod1 and Nod2 in adaptive immune responses. The peptidoglycan products that activate Nod proteins are known adjuvants of antigen specific antibody production (2-5). Nod2 has been shown to regulate Th17 cell responses in experimental colitis models, to program human dendritic cells to secrete IL-23 and to drive development of Th17 cells from memory T cells (6, 7). Stimulation of either Nod1 or Nod2 leads to Th2-dependent responses (8, 9) and both proteins contribute to IL-6-dependent induction of Th-17 cell responses (10).

Nod1 is widely expressed in a variety of cell types, and Nod2 is found in hematopoietic cells and epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract and the kidney (1). Altering Nod1 and Nod2 signaling has the potential to modify inflammatory disease activity (1), and therefore it is no surprise that small molecule therapeutics are being developed to specifically target these cytosolic PRRs (11-13). A rational approach to modifying the activity of Nod1 and Nod2-mediated inflammation requires an understanding about how these proteins contribute to adaptive immunity. To better understand how Nod1 and Nod2 proteins contribute to T cell responses, we investigated their role in alloantigen-induced T cell activation and asked whether their absence impacted in vivo alloresponses using a severe acute graft versus host disease model.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All the mice used in these experiments were housed in the vivarium at UCSD and approved for use by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the UCSD Animal Research Center. All animals were handled according to the recommendations of the Humanities and Sciences and the Standards of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor MN. The Nod1-/-, Nod2-/- and Nod1x2-/- mice were obtained from J. Matheson at the Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA.

Relative Expression of Nod1 and Nod2 in T cells

Expression of Nod1 and Nod2 was detected in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells isolated from peripheral lymph nodes (LNs) of WT mice. To ensure that the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were not contaminated with dendritic cells (DCs) we labeled the cells with anti-CD11c and anti-CD11b antibodies followed by positive selection with magnetic beads, and then negatively selected the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell population using a magnetic cell isolation and cell separation column (MACS®). Confirmation of T cell purity (>98%) was done by FACS. Expression of Nod1 and Nod2 was measured by SYBR green-based real-time PCR according to the manufacturer's recommendations (SsoAdvanced Sybr Green SuperMix, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with an Eco Real-Time PCR system (Illumina, San Diego, CA). The amount of mRNA was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method as previously described (14) using a SuperScript III RT kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Nod1, Nod2 and GAPDH primers were purchased from Qiagen (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA).

T cell proliferation and FASL blockade

The ability of T cells to proliferate to allogeneic APCs was determined in a standard mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assay. CD3 T cells obtained from fresh LN suspensions from WT, Nod1-/-, Nod2-/- or Nod1x2-/- mice (2×10ˆ5) (all H-2b) were cultured with irradiated (2000 rad) spleen cells (2×10ˆ5) from BALB/c mice (H-2d). Cultured cells were grown in round-bottom plates (Costar, Corning, NY) in 10K medium [RPMI 1640 (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% FCS, penicillin, streptomycin and 2-ME (50 lM)] (all reagents from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Proliferation to CD3/CD28 was tested in 96-well flat-bottom plates bound with 5ug/ml of anti-CD3e and 5ug/ml of soluble anti-CD28 (all reagents from Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Detection of individual CD4 and CD8 T cells responses was accomplished by isolating the T cell subsets from WT or the Nod1x2-/- LNs (isolated to >90% purity by MACS separation columns, Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA) and added at a density of 1×10ˆ5 cells per round-bottom well. Proliferation was measured by [3H] thymidine incorporation during the final 8 hours in culture and also by using a non-radioactive cell proliferation assay (MTT) (Promega, Madison WI). To assess the effect of FasL blockade on the allogeneic T cell proliferation, anti-FasL antibody (BioLegend, San Diego CA), at concentration of 2 ug/ml, was added to the MLR cultures at day 0. T cell proliferation was then measured using a MTT assay.

T cell phenotype

The phenotype of T cells was determined by isolating T cells from LNs of WT versus Nod1x2-/- mice and staining with indicated antibodies for detection by flow cytometry. The relative percentage of T regulatory cells was determined by gating for either CD4/CD25/FoxP3+ or for CD8T/CD25/FoxP3+ cells (BioLegend, San Diego, CA).

Cytotoxicity assay

CD8+ T cells were selected from LNs of WT versus Nod1x2-/- mice by magnetic bead separation using a MACS column kit (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) on day -1 and stimulated overnight by CD3/CD28 in flat-bottomed plates (at density of 1×10ˆ5 cells) in serum-free media (37 °C, 5% CO2). At day 0, 1×10ˆ5 target cells [SP2 (H-2d) or EL4 (H-2b) cells (generous gift from Dr. Joseph Cantor, UCSD] were added to the culture wells to achieve an effector to target ratio of 1:1. LDH release by the target cells was measured at 5hr using the CytoTox non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay (Promega, Madison, WI).

T cell signaling events

To evaluate T cell signaling events, CD3 T cells (2×10ˆ6/gp) isolated from LNs of WT versus Nod1x2-/- mice were stimulated with anti-CD3e and anti-CD28 antibodies (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) for times noted in the figure legends, in a water bath at 37°C. Following stimulation, T cells were washed, pelleted at 1200 rpm for 5 min (at 4°C), and lysed in 4°C buffer containing the following protease inhibitors: leupeptin (30ug/mL), aprotinin (30ug/mL), sodium flouride (10mM), sodium orthovanadate (1mM), sodium pyrophosphate (10mM) and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (2mM). Lysate protein was normalized and equal amounts of protein (40ug) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with the detection antibody of interest: anti-cleaved caspase-8; anti-cleaved caspase-3; anti-phospho-MDM2; anti-p53; anti BAX; or anti-beta actin as a loading control (all reagents from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). The blots were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Apoptosis and mitochondrial damage

Proliferating T cells were analyzed for the cell surface expression of death markers CD95L, CD95 and TNFRa and markers of apoptosis (Annexin V and PI) (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) by flow cytometry. Mitochondrial damage was detected in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by staining for mitochondrial membrane potential with mitoprobe JC-1 (5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolocarbocyanine iodide stain) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly the CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were stimulated with CD3e+CD28 (5ug/mL) for 24 hrs and then suspended in PBS at density of 1×10ˆ6 cells/mL. The JC-1 dye was then added to the tubes to obtain a final concentration of 2 uM. For the positive control, unstimulated cells were suspended at 1×10ˆ6 cells/mL and CCCP (Carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone) was added to obtain a final concentration of 50 uM, followed by JC-1 dye at final concentration of 2 uM. The cells were then incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes. At end of incubation time the cells were washed with warm PBS and analyzed on a flow cytometer using CCCP-treated sample as standard compensation.

Bone marrow transplantation and acute GVHD assessment

Recipient mice (BALB/c) were irradiated at day -1 with two doses of 450 cGy separated by 4 hours to diminish GI toxicity. Donor bone marrow was harvested from WT or Nod1-/-, Nod2-/- or Nod1x2-/- mice. CD3 T cells were depleted from the bone marrow by negative selection using magnetic beads and MACS column (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). WT versus Nod1-/-, Nod2-/- or Nod1x2-/- T cell-depleted bone marrow cells (1×10ˆ7) supplemented either CD3, CD4 or CD8 donor T cells (5×10ˆ5) from the WT versus Nod1x2-/- mice were then injected via tail vein into the allogeneic recipient mice.

To assess for the presence of donor T cells in host mice, recipient mice were sorted into three different groups: one group received T-cell depleted WT or Nod1x2-/- bone marrow supplemented with CD3+ T lymphocytes, (from either WT or Nod1x2-/- mice); another group received T-cell depleted WT or Nod1x2-/- bone marrow supplemented with CD8+ T lymphocytes (from either WT or Nod1x2-/- mice); and another group received T-cell depleted WT or Nod1x2-/- bone marrow supplemented with CD4+ T lymphocytes (from either WT or Nod1x2-/- mice). In each case the same donor BM/T cell source was used (e.g., WT bone marrow and WT T cells or Nod1x2-/- BM and Nod1x2-/- T cells). Recipient mice were sacrificed on days 1, 3 and 7 following bone marrow transplantation and the number of donor T cells in blood and lymphoid organs (spleen, lymph nodes, thymus) were assessed. Briefly, the spleen, lymph nodes, thymus and blood were collected from the recipient mice and processed to obtain single cell suspensions for each followed by RBC lysis. The samples were analyzed by FACS for H2Kb/CD3+, H2Kb/CD4+, H2Kb/CD8+ and H2Kb/CD4/CD25/FOXP3+ donor T cells (using indicated antibodies obtained from Biolegend, San Diego, CA).

To assess for acute graft versus host disease (GVHD), another group of mice was monitored on a daily basis and assessed for weight loss, posture, activity, fur texture and skin integrity based on the clinical GVHD reporting scale previously published (15). Injections of BM with CD8 T cells from either WT or Nod1x2-/- mice did not induce GVHD and were not included in the data presented.

Statistical analysis

The p values were calculated using an unpaired two-tailed t test. Asterisks located above the horizontal lines indicate comparisons between the two experimental groups. Sample sizes and numbers of experimental trials are indicated within the figure legends.

Results

To better understand whether Nod1 and Nod2 receptors might provide a rational target for modifying adaptive immune responses, we investigated their role in alloantigen-induced T cell activation.

Nod-deficient T cells demonstrate defective proliferation to alloantigen and to CD3/CD28 stimulation

Examining T cells for expression of Nod1 and Nod2 demonstrated that both receptors were constitutively expressed in naive CD4 and CD8 T cells from WT (C57BL/6) mice, although there was more Nod2 detected in CD8 T cells by mRNA analyses (Figure 1, Panel A). Confirmation of Nod1 and Nod2 protein in both CD4 and CD8 T cells was done by immunoblotting for Nod1 and Nod2 in lysates of T cells purified from DC-depleted LNs of WT versus Nod1-/- or Nod2-/- mice (Figure 1, Panel B). Neither Nod1 nor Nod2 was induced by T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 1. Impact of NOD-deficiency on antigen-induced proliferation.

Panel A. Expression of Nod1 (black bars) and Nod2 (grey bars) mRNA in CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes isolated from WT (C57BL/6) mice. CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were positively selected, then depleted of DCs, and then negatively selected by magnetic bead sorting and total RNA was isolated. Nod1 vs. Nod2 mRNA was detected by quantitative RT-PCR. Error bars represent SD of 3 mice/gp. The graph represents one of three identical experiments. Panel B. Expression of Nod1 and Nod2 protein in CD4 and CD8 T cells from WT mice. Comparisons were made with T cells isolated from Nod1-/- and Nod2-/- mice. The Western Blot represents one of two experiments with identical results. Panel C. Proliferation of T lymphocytes (2×105/well), from WT (square), Nod1-/- (Nod1-/-, triangle), and Nod2-/- (Nod2-/-, circle) mice (all H-2b), over time in response to irradiated BALB/c (H-2d) splenocytes (2×105/well). Panel D. Proliferation of (2×105/well) T lymphocytes, from WT (square), and Nod1x2-/- (Nod1x2-/-, triangle) mice (all H-2b), over time in response to irradiated BALB/c splenocytes (2×105/well). Panel E. Proliferation of (2×105/well) CD4+ T lymphocytes, from WT (square), or Nod1x2-/- (Nod1x2-/-, triangle) mice (all H-2b), over time in response to irradiated BALB/c (H-2d) splenocytes (2×105/well). Panel F. Proliferation of (2×105/well) CD8+ T lymphocytes from WT (square) or Nod1x2-/- (Nod1x2-/-, triangle) mice (all-H-2b), over time in response to irradiated BALB/c splenocytes (2×105/well). Panel G. Proliferation of CD4+ T lymphocytes (1×105/well) from WT (square) versus Nod1x2-/- (Nod1x2-/-, triangle) mice to anti-CD3e + anti-CD28 (both antibodies used at 5ug/mL) over time. Panel H. Proliferation of (1×105/well) CD8+ T lymphocytes from WT (square) versus Nod1x2-/- (Nod1x2-/-, triangle) mice to anti-CD3e + anti-CD28 (both 5 ug/mL) over time. In each of the panels above proliferation was measured by thymidine uptake during the last 8 hours of culture. Error bars represent SD of three samples in each panel. The graphs represent one of three identical experiments. For all panels, *p<0.05; **p<0.005; ***p<0.0005.

To determine whether these cytoplasmic proteins play a role in antigen-dependent T cell responses, T cells from WT or Nod-deficient mice were exposed to allogeneic antigen presenting cells and their proliferative responses assessed in a mixed lymphocyte assay (MLR) (Figure 1, Panel C to H). While WT T cells (C57BL/6, H-2b) proliferated vigorously to allogeneic (BALB/c, H-2d) antigen presenting cells (APCs), T cells from mice deficient in either Nod 1 or Nod 2 (both H-2b) demonstrated depressed proliferative responses to alloantigen (Figure 1, Panel C). Since there is known cross-talk between these proteins (16), we harvested T cells from mice deficient in both Nod1 and Nod2 and saw that proliferation was affected to an even greater degree by the simultaneous absence of these proteins (Figure 1, Panel D and Supplementary Figure 1). The deficiency in Nod signaling affected both CD4 and CD8 T cells, as shown in Figure 1, Panels E and F respectively. T cell proliferation to CD3/CD28 stimulation was similarly affected by the simultaneous deficiency in both Nod proteins. Figure 1, Panels G and H, show that Nod1x2-/- CD4 (Figure 1, Panel G, Nod1x2-/-) and CD8 (Figure 1, Panel H, Nod1x2-/-) T cells both showed impaired TCR -mediated proliferation.

Nod-deficient and WT T regulatory cells are induced after antigen exposure and Nod-deficient CD8 T cells demonstrate intact cytotoxic functions

Since Nod2 has been shown to regulate the survival of human T regulatory cells (17), one explanation for the defective proliferative responses shown in Figure 1 could be that the absence of Nod proteins led to the expansion of induced regulatory T cells. Figure 2 Panels A-C show MLR cultures assayed over time for development of CD4 and CD8 T regulatory cells (Tregs). As shown in Figure 2, Panel B, CD4 and CD8 (Day 1 and Day 4, black line WT, red line Nod1x2-/-), there were no significant differences in FOXP3 expression between WT versus Nod1x2-/- T cells based on FACS analyses. Quantitative assessment of total CD25/FoxP3+ cells over time also showed no differences in the development of regulatory T cells between WT and Nod1x2-/- MLR cultures (Figure 2, Panel C), suggesting that decreased proliferation of the Nod-deficient T cells in vitro was not due to the preferential expansion of antigen-induced regulatory T cells.

Figure 2. Regulatory T lymphocytes and CD8 target cell lysis.

Panel A gating strategy to determine T cell frequencies and CD4 and CD8 T regulatory cells isolated from WT versus Nod1x2-/- mice. Panel B is a histogram showing staining for FOXP3+ cells on day 1 and day 4 of MLR culture. Tregs were detected by gating on CD4+/CD25+/FoxP3+ or CD8+/CD25+/FoxP3+ cells in WT (black line) versus Nod1x2-/- (grey line) MLR cultures (MLR culture conditions were the same as described in Figure 1. This experiment represents one of two similar experiments with identical results. The solid black (WT) and solid grey (Nod1x2-/-) histograms are unstimulated controls. Panel C shows percentage of CD25/FOXP3+ cells that developed over time of MLR culture, comparing T cells isolated from WT (black bar) versus Nod1x2-/- (grey bar) mice. This experiment represents one of two similar experiments with identical results. Error bars represent SD of 3 samples/group. Panel D shows cytolytic activity of CD8 T lymphocytes isolated from WT (black bars) versus Nod1x2-/- T cells (grey bars) (all H-2b) to EL4 (syngeneic, H-2b) versus SP2 (allogeneic, H-2d) target cells. The results represent one of two identical experiments. Error bars represent standard deviations of 3 samples/group.

The absence of the Nod proteins appeared to affect the proliferative responses of CD8 T cells more than CD4 T cells (as shown in Figure 1), and so we also tested whether the absence of Nod proteins conferred additional defects in CD8 T cell function. Shown in Figure 2, Panel D there were no differences in the ability of Nod1x2-/- CD8 T cells to lyse allogeneic target cells (SP2), showing that the NOD deficiency did not affect CD8 T cell cytotoxic responses.

Nod1x2-/- T cells undergo activation-induced cell death upon antigen exposure

To further understand the reason for the proliferative defect in the absence of Nod1 and Nod2, we tested whether the absence of these proteins impacted T cell survival. As shown in Figure 3 Panel A, the Nod1x2-/- T cells underwent accelerated cell death upon exposure to alloantigen, as evidenced by increased uptake of 7AAD and Annexin V in the Nod1x2-/- T cells. The same trend was seen for CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets (Figure 3, Panel B, CD3, CD4, CD8 respectfully).

Figure 3. Increased T cell death with the simultaneous absence of Nod1 and Nod2 proteins.

Panel A shows the gating strategy used to determine H2Kb+, 7-amino actinomycin D (7-AAD) and Annexin V + on CD3 lymphocytes. The same gating strategy was used for CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes. Panel B shows the percentage of CD3+, CD4+ or CD8+ T lymphocytes isolated from either WT (black bars) or Nod1x2-/- (stippled bars) mice that uptake Annexin V and 7-AAD after stimulation with irradiated allogeneic (BALB/c) splenocytes on days 0 to 4 after MLR culture. Error bars represent SD of three samples. The graph represents one of 4 identical experiments. *p<0.05; **p<0.005

To clarify the mechanisms of cell death in the Nod1x2-deficient T cells, we tested for acquisition of known death receptors following alloantigen exposure. MLR cultures assayed over time showed that antigen-induced stimulation of the Nod-/- T cells was associated with significantly increased expression of CD95L and CD95 on CD8 T cells (Figure 4, Panel B, CD95L, CD95, CD8), and a trend to increased expression on CD4 T cells by day 4 of culture (Figure 4, Panel B, CD95L, CD95, CD4). No differences were however noted in the expression of tumor necrosis factor 1 receptor (TNFR1) expression between the Nod1x2-/- CD4 or CD8 T cells, or their WT counterparts (Figure 4, Panel B, TNFR1, CD4, CD8).

Figure 4. T lymphocytes from Nod1x2-/- mice undergo cell death signaling after exposure to antigen.

Panel A shows the gating strategy to determine the relative frequencies of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes isolated from WT versus Nod1x2-/- mice. Panel B shows cell surface expression of CD95L (FASL), CD95 (FAS) or TNFR1 on CD4+ versus CD8+ T cells from WT (black bars) or Nod1x2-/- (stippled bars) mice. The T cells were stimulated with allogeneic (BALB/c) splenocytes and isolated from the MLRs on serial days for staining with the indicated antibodies and analysis by flow cytometry. Error bars represent SD of three samples. *p<0.05; **p<0.005; ***p<0.0005. The graph represents one of 3 identical experiments. Panel C shows cleaved caspase 8 and caspase 3 following 24 hr of anti-CD3 + anti-CD28 (5 ug/mL) stimulation in T lymphocytes isolated from WT versus Nod1x2-/- mice. The Western blot represents one of 5 experiments with identical results. Panel D shows T lymphocytes isolated from WT versus Nod1x2-/- mice stimulated with anti-CD3 + anti-CD28 (5 ug/mL) for indicated times (0-12hr) and lysates immunoblotted with anti-pMDM2, anti-p53, or anti-Bax. This represents one of 3 experiments with identical results. Panel E shows gating strategy (left panels) and staining with the mitoprobe JC-1 (right panels) in CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes from WT (grey line) versus Nod1x2-/- T cells (black line), versus the CCCP positive control (solid grey) 24 hr after co-stimulation with anti-CD3 + anti-CD28 (5 ug/mL). The histogram represents one of 3 experiments with identical results. Panel F shows the percentage increase in WT (black bars) versus Nod1x2-/- (grey bar) T cell proliferation over no added antibody in response to alloantigen in the presence of FASL blockade. The MLR cultures were treated with anti-FASL antibody and stimulated with irradiated BALB/c splenocytes. The data represent one of 2 experiments with identical results. Error bars represent SD of three samples/group.

We next asked whether the absence of Nod1 and 2 proteins conferred specific alterations in signaling associated with Fas/FasL-mediated cell death. We found that TCR stimulation of the Nod1x2-/- T cells led to greater caspase 8 and caspase 3 cleavage compared to stimulation of WT T cells (Figure 4, Panel C, c-caspase 8 and c-caspase 3 respectively). As shown in Figure 4 Panel D, stimulation of WT and Nod1x2-/- T cells also induced activation of other proteins important to cell death signaling, including the tumor suppressor p53. Upregulation of p53 is associated with increased Fas expression (18) and, as shown in Figure 4 Panel D (p53), we found that increased p53 expression was sustained in the Nod1x2-/- T cells. Accompanying the sustained p53 stabilization was decreased expression of its negative regulator, the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase MDM2 (Figure 4, Panel D, pMDM2), as well as sustained Bax expression over time (Figure 4, Panel D, Bax). There were however, as expected, no differences in phosphorylation of BID between the stimulated WT and NOD-deficient T cells (Supplementary Figure 2). Mitochondrial membrane potential was also found to be disrupted following CD3/CD28 stimulation of both CD4 and CD8 T cells from Nod1x2-/- mice, as detected by the JC-1 fluorochrome (Figure 4, Panel E). Adding anti-FASL antibody to the MLR cultures showed that there were no significant differences between the proliferation of WT versus Nod1x2-/- T cells to alloantigen in the presence of the anti-FASL antibody. The figure shows percentage increase in proliferation over no added antibody (Figure 4, Panel F). These data suggest that one-way Nod1 and Nod2 signaling might provide an anti-apoptotic signal is by interfering with Fas/FasL–mediated cell death.

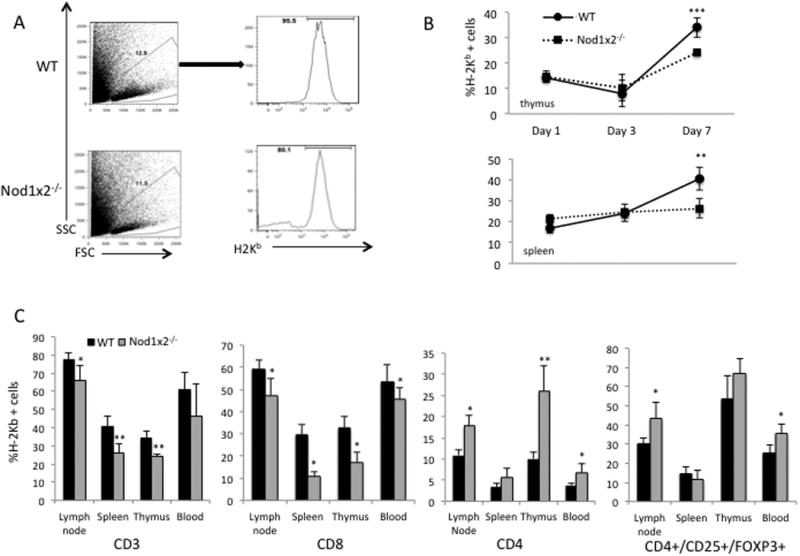

We next asked whether Nod1x2-/- T cells underwent cell death in vivo after exposure to alloantigen. We compared WT versus Nod1x2-/- T cell depleted bone marrow supplemented with exogenous T cells (CD3+, CD4+ or CD8+) from WT versus Nod1x2-/- mice into allogeneic hosts (Figure 5, Panels B and C). Donor T cells and bone marrow from either WT or Nod1x2-/- mice (all H-2b) were injected into tail veins of lethally irradiated BALB/c recipient mice (H-2d), and peripheral and central lymphoid tissues assayed for the presence of the H-2b donor cells. As shown in Figure 5 Panel B, there were identical numbers of donor H-2b cells detected early after injection of the WT versus Nod1x2-/- donor inoculum, but, by 7 days after injection significantly fewer Nod1x2-/- donor cells were detected in the spleen and thymus of the allogeneic recipient mice (Figure 5, Panel B). This is consistent with enhanced AICD in Nod1x2-/- T cells. We observed significantly fewer CD3 and CD8, Nod1x2-/- T cells in the allogeneic recipients than WT CD3 and CD8 T cells (Figure 5, Panel C, CD3 and CD8 respectfully). Interestingly, however, there were significantly more Nod1x2-/- CD4 T cells in host LNs, thymus and blood compared to WT CD4 T cells (Figure 5, Panel B, CD4). Further analyses showed the higher numbers of CD4 T cells were due to an increase in donor Tregs, in the recipients injected with Nod1x2-/- T cells, suggesting that the absence of the NOD proteins led to increased antigen-induced CD4 Treg development in vivo (Figure 5, Panel B, CD4/CD25/FOXP3+).

Figure 5. Presence of WT versus Nod1x2-/- donor T lymphocytes in central and peripheral lymphoid tissue of allogeneic recipient mice at intervals after bone marrow transplantation.

Panel A shows the representative gating strategy in lymphocytes derived from the recipient mice to determine percentage of engrafted CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ H-2b+ donor T cells. Panel B shows the percentage of H-2b donor cells in the thymus versus spleen on day 1, day 3 and day 7 after injection into allogeneic recipients (BALB/c, H-2d) injected with either WT (straight line, circle) or Nod1x2-/- (dashed line, square) donor T cells. Panel C shows the percentages of CD3, CD8, CD4 and CD4/Treg donor WT (black bars) versus Nod1x2-/- (grey bars) T lymphocytes in indicated tissues of recipient (BALB/c, H-2d) mice. The BALB/c recipient mice that received WT (black bars) or Nod1x2-/- (gray bars) bone marrow and T cells were sacrificed on day 7 for assessment of donor cells (H-2b) in blood and lymphoid organs (spleen, lymph nodes, thymus) of recipient mice. The graph represents one of 5 identical experiments. Error bars represent SD of seven animals and *p<0.05; **p<0.005; ***p<0.005.

Nod1x2-/- T cells protect from severe graft versus host disease

Antigen exposure caused Nod1x2-/- T cells to die in vitro and in vivo, so we next asked whether the absence of these PRRs in the donor inoculum protected recipients from graft versus host disease (GVHD). We used a model of severe acute GVHD, where there was a complete MHC-mismatch between the donor and recipient (H-2b donor, H-2d recipient); BM and T cells from WT versus Nod1-/-, Nod2-/- or Nod1x2-/- donor mice were transferred to lethally irradiated allogeneic recipients, as described in materials and methods.

As shown in Figure 6, Panel A, mice injected with the WT or Nod1-/- or Nod2-/- inoculum developed severe GVHD and rapidly died, whereas those injected with the Nod1x2-/- inoculum had significantly prolonged survival. A delay in weight loss and adverse clinical score parameters was seen in recipients of Nod1x2-/- bone marrow and CD3 T cells (Figure 6, Panel B) or CD4 T cells (Figure 6, Panel C), demonstrating that the simultaneous absence of Nod1 and Nod2 provided protection from GVHD.

Figure 6. Acute severe GVHD in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow and T lymphocytes from WT versus Nod1-/-, Nod2-/- or Nod1x2-/- mice.

Panel A shows Kaplan Meyer survival curves of recipients of allogeneic WT (dotted line) versus Nod1-/- (dot/dashed line) or Nod2-/- (dashed line) or Nod1x2-/- (straight line) bone marrow supplemented with CD3 T cells. Panel B top panel shows survival of allogeneic WT (straight line) versus Nod1x2-/- BM + CD3 T cells (dashed line). The middle panel of B shows percentage weight loss over time and the bottom panel shows clinical GVHD scores (assessed based on weight loss, posture, fur texture, and skin integrity) of recipient mice. Panel C top panel shows survival of allogeneic WT (straight line) versus Nod1x2-/- BM + CD4 T cells. The middle panel of Panel C shows percentage weight loss over time and the bottom panel shows clinical GVHD scores of recipient mice. The graph represents one of 4 identical experiments. Error bars represent SD of six mice per group and *p<0.05; **p<0.005; ***p<0.005.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that the concurrent absence of two of the best-characterized Nod family members, Nod1 and Nod2, is associated with increased T cell death after encounter with alloantigen. In the absence of both Nod1 and Nod2, the p53 tumor suppressor is stabilized, there is decreased expression of the p53 negative regulator MDM2 and T cells exposed to antigen undergo activation-induced cell death (AICD).

Nod1 and Nod2 proteins are known to be expressed in T cells (19-21), and their expression can be upregulated by several stimuli, including bacterial cell wall products, TLR ligands, IFNg and TNFa (22-24). We confirmed the expression of these proteins in WT T cells, and found Nod2 and Nod1 were expressed in both CD4 and CD8 T cells from naïve WT mice. We did not see upregulation of either Nod1 or Nod2 when WT T cells were stimulated through the TCR, possibly because upregulation of these proteins requires additional signals independent of TCR-mediated signals.

Nods have been demonstrated in several published studies to play an important role in T cell function (17, 19, 21, 25). Nod2 has been shown to be functionally important in Tregs derived from the lamina propria mucosae of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, where Nod2 appears to regulate Fas-mediated apoptosis in the T cells (17). In the absence of Nod-mediated apoptosis, Tregs are dysfunctional, which has been proposed as a possible link to Crohn's disease. Thus, one function of Nod2 might be to provide protection against death-receptor-mediated apoptosis in a Fas ligand-rich environment, such as that of the inflamed intestinal subepithelial space (17).

In a model of T. gondii infection, Nod2 has been found to provide a T cell intrinsic signal that is necessary not only for generating protective Th1 immunity to T. gondii, but also for driving T cell-mediated colitis (25). Using in vivo transfer experiments Shaw et al also showed a T cell-intrinsic role for Nod2 that dictated the generation of an effective Th1 response and showed that Nod2 was required for optimal IL-2 production by the activated T cells (25). Impaired T cell function in the absence of Nod2 also included lymphopenia-induced T cell population expansion and T cell driven colitis, two model systems that are driven by interaction of the TCR and the coreceptor CD28 with complexes of peptide, major histocompatibility complexes and with B7 molecules on accessory cells. TCR signaling was largely intact in the absence of Nod2, however it was suggested that Nod2 acted downstream of the CD28 signaling pathway. Their data showed not only that Nod2 could interact with c-Rel, but also that this interaction facilitated the nuclear entry of c-rel required for IL-2 transcription. They proposed that Nod2, in addition to sensing microbial products in innate immune cells such as macrophages and DCs, could also operate as a molecular scaffold that integrates costimulatory signals necessary for proper T cell function. The influence of Nod2 on adaptive immune responses in vivo therefore might be determined by whether or not CD28 signaling is preferentially required.

Nod2 is also expressed in memory CD4 T cells, however its functional role in this T cell subset is not known at this time (21). In CD8 T cells, Nod1 has been shown to cooperate with TLR2 to enhance TCR-mediated activation, suggesting that Nod1 might function as an alternative costimulatory receptor in both human and murine CD8 T cells (19).

In addition to signaling the presence of pathogens, Nods are thought to play an important role in intestinal lymphoid tissue genesis (26), the generation or maintenance of functional Paneth cells in the intestine (5, 27) and systemic neutrophil priming at sites distal to the gut (28). More recent data show that both Nod1 and Nod2 promote CD8 single positive thymocyte-positive selection and Nod ligands can promote thymocyte maturation in culture (29), suggesting a T cell intrinsic role in thymocyte maturation events.

Our results showed that the simultaneous absence of Nod1 and 2 proteins affected both alloantigen- and CD3/CD28-induced T cell activation. These findings agree with those of Watanabe et al who found that Nod2-/- mice have increased sensitivity to experimental colitis driven by T helper type 1 cells and increased IL-12 release (30, 31). Our findings differed however from that of Penack et al, who found no impairment of Nod2 deficient T cell proliferation to irradiated BALB/c spleen cells (32). While there was an initial proliferative boost in the Nod deficient T cells in our study, it was followed rapidly by T cell death. It is possible that monitoring proliferation at a single time point in Penack's study did not detect the subsequent decline in proliferative responses of the dying Nod–deficient T cells. It is also possible that microbial exposure in the different mouse colonies might explain the different experimental results, as Nod2 is known to have a bidirectional relationship with commensal microbes (27).

We believe that both the mitochondrial death pathway and FasL/Fas pathways are activated in the absence of Nod1 and Nod2 proteins. The absence of Nod proteins appears to be associated with stabilized p53 expression. p53 has been associated with both intrinsic (by promoting permeabilization of mitochondrial outer membranes– (33-35)) and extrinsic cell death pathways (through p53 response elements in the Bax gene (36)). We have observed increased Bax phosphorylation, which is consistent with the observed increased p53 in the Nod1x2 deficient cells. We did not observe a difference in phosphorylation of BID, in either WT or Nod1x2 deficient T cells, suggesting that BID does not play a primary role in mitochondrial destablization in the simultaneous absence of Nod1 and Nod2.

Nod-LRR proteins have been identified by their structural homology to the apoptosis regulator, Apaf-1, suggesting that these proteins may regulate apoptosis. The role of Nod2 in apoptosis of intestinal Tregs was discussed above (17). There are several other studies pointing to a direct role for Nod1 and Nod2 in apoptosis (17, 37). Nod1 signaling has been shown to lead to activation of apoptosis through caspase and JNK activation (37). MDP has been shown to protect against Fas-mediated apoptosis, and caspase activation is decreased in MDP-stimulated cells exposed to FasL. Overexpression of Nod1 and Nod2 has been shown to promote apoptosis (38), however these proteins also activate NF-kB, which induces the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins. Therefore, it is possible that under physiological conditions apoptosis induced through Nod-LRR proteins might depend on the sum of several signals (38).

Our data confirm that both CD4 and CD8 T cells deficient in the Nod proteins experienced destabilization of mitochondrial membrane potential and increased cell death through intrinsic apoptotic cell death signals. We also found that extrinsic cell death pathways were involved, at least in CD8 T cell death with the simultaneous absence of Nod1 and Nod2. While we did not see a significant increase in FAS/FAL expression on CD4 T cells, there was a trend over time to increased expression on these cells, which might contribute to the increased susceptibility of these cells to AICD. Since AICD in CD4+ T cells is influenced by both cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic variables (39), however it is also possible that CD4 T cells might be less responsive to FAS-mediated cells death signals, as has been reported by others (39-41).

Our in vitro data suggest that Nod proteins are required for autonomous T cell responses to allostimulation, however it is also possible that the Nod-deficient T cells, which develop in an environment in which Nod1 and 2 are absent in all cells, might be aberrantly primed to undergo cell death when challenged with antigen. There are published examples in which both cell autonomous and cell non-autonomous mechanisms govern T cell responses to antigen and apoptosis signals in animal models. A cell autonomous role has been identified for the cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen (CTLA)-4 in activated T cells, however T regulatory cells can modify CD80 and CD86 expression of APCs and therefore in a non-autonomous manner they can reduce their ability to prime effector T cells, leading to suppression and immune tolerance (42-44). Likewise, nonautonomous control of apoptosis, in which the dying cell influences either cell death or proliferation in nearby cells has been reported in multicellular organisms such as C. elegans (45). Since proper regulation of apoptosis is critical for suppressing disease, understanding how these proteins function in vivo and how they might regulate other cells in their environment under conditions associated with allograft rejection is mandatory before the development of therapeutic clinical targets. Clearly, a better understanding of the dynamic versus developmental role of Nod proteins in vivo requires additional studies using chimeric animal models and/or cre-lox systems as reported by others (46-48), that are directed to answer the fundamental questions about autonomous versus nonautonomus roles of regulatory proteins that impact T cell function.

Clues to the in vivo significance of the Nod1x2 deficiency were obtained from our study when we used a lethal acute GVHD model in which the donor inoculum contained either WT or Nod1x2-/- T cells. The simultaneous absence of both Nod1 and Nod2 proteins significantly prolonged the survival and markedly delayed the onset of weight loss and clinical score of severe acute GVHD, particularly in the inoculum containing Nod1x2-/- CD4 donor T cells. Interestingly, the deletion of only Nod1 or Nod2 alone did not protect from GVHD in our model, suggesting redundancy in Nod1 and Nod2 signaling contributes to GVHD in vivo.

SNPs in the Nod2 gene locus have been linked to GVHD in humans, leading to a higher incidence of disease and increased mortality following BM transplant (49, 50), although there are contradictory clinical studies questioning the relevance of the Nod2 deficiency in donor bone marrow on the development of acute GVHD (32, 51). It has been known for some time though that expansion of Tregs provides protection from lethal acute GVHD (52-54), which is consistent with the additional protection conferred by the donor inoculum containing the Nod1x2-/- CD4 donor T cells. Interestingly, we found that Tregs were increased in vivo when Nod1 and Nod2 were both absent, which may explain the survival benefit conferred by the Nod-deficient donors. Although we did not see expansion of Tregs in vitro, the complex microenvironment induced by the conditioning regimen in the GVHD model likely provides additional signals that are needed for the induction of Tregs. Nod2 variant genotypes have been linked in humans to Treg survival and MDP stimulation of human Tregs protects cells from Fas-mediated apoptosis (17), consistent with the absence of Nod proteins priming for Fas-mediated cell death.

Our findings of delayed onset of acute GVHD, accompanied by the in vitro findings of antigen-induced cell death, lead to the postulate that T cells deficient in both Nod1 and Nod2 proteins undergo activation induced cell death upon encounter with alloantigen due to both intrinsic and extrinsic cell death pathways. The absence of Nod1 and 2 proteins appears to have a profound effect on antigen-induced T cell responses, suggesting that these intracellular PRRs might provide a novel target to block T cell activation associated with exposure to alloantigen, a strategy highly applicable to immunosuppressive therapies used to prevent allorecognition in bone marrow or solid organ transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank John Matheson, Ph.D. from the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, CA for providing the Nod1-/-, Nod2-/- and Nod1x2-/- mice used in this study. They would also like to thank Dr. Joseph Cantor from UCSD for providing the EL4 and SP2 cell lines.

The work presented in this manuscript was supported by grants awarded to DBM from the NIH R01 DK091136, R01 DK075718 and CIRM RB5-07379.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Caruso R, Warner N, Inohara N, Nunez G. NOD1 and NOD2: signaling, host defense, and inflammatory disease. Immunity. 2014;41:898–908. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellouz F, Adam A, Ciorbaru R, Lederer E. Minimal structural requirements for adjuvant activity of bacterial peptidoglycan derivatives. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974;59:1317–1325. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(74)90458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Viala J, Chamaillard M, Labigne A, Thomas G, Philpott DJ, Sansonetti PJ. Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8869–8872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inohara N, Ogura Y, Fontalba A, Gutierrez O, Pons F, Crespo J, Fukase K, Inamura S, Kusumoto S, Hashimoto M, Foster SJ, Moran AP, Fernandez-Luna JL, Nunez G. Host recognition of bacterial muramyl dipeptide mediated through NOD2. Implications for Crohn's disease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5509–5512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi KS, Chamaillard M, Ogura Y, Henegariu O, Inohara N, Nunez G, Flavell RA. Nod2-dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Science. 2005;307:731–734. doi: 10.1126/science.1104911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Beelen AJ, Zelinkova Z, Taanman-Kueter EW, Muller FJ, Hommes DW, Zaat SA, Kapsenberg ML, de Jong EC. Stimulation of the intracellular bacterial sensor NOD2 programs dendritic cells to promote interleukin-17 production in human memory T cells. Immunity. 2007;27:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brain O, Owens BM, Pichulik T, Allan P, Khatamzas E, Leslie A, Steevels T, Sharma S, Mayer A, Catuneanu AM, Morton V, Sun MY, Jewell D, Coccia M, Harrison O, Maloy K, Schonefeldt S, Bornschein S, Liston A, Simmons A. The intracellular sensor NOD2 induces microRNA-29 expression in human dendritic cells to limit IL-23 release. Immunity. 2013;39:521–536. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fritz JH, Le Bourhis L, Sellge G, Magalhaes JG, Fsihi H, Kufer TA, Collins C, Viala J, Ferrero RL, Girardin SE, Philpott DJ. Nod1-mediated innate immune recognition of peptidoglycan contributes to the onset of adaptive immunity. Immunity. 2007;26:445–459. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magalhaes JG, Fritz JH, Le Bourhis L, Sellge G, Travassos LH, Selvanantham T, Girardin SE, Gommerman JL, Philpott DJ. Nod2-dependent Th2 polarization of antigen-specific immunity. J Immunol. 2008;181:7925–7935. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geddes K, Rubino SJ, Magalhaes JG, Streutker C, Le Bourhis L, Cho JH, Robertson SJ, Kim CJ, Kaul R, Philpott DJ, Girardin SE. Identification of an innate T helper type 17 response to intestinal bacterial pathogens. Nat Med. 2011;17:837–844. doi: 10.1038/nm.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geddes K, Magalhaes JG, Girardin SE. Unleashing the therapeutic potential of NOD-like receptors. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2009;8:465–479. doi: 10.1038/nrd2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jakopin Z. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD) inhibitors: a rational approach toward inhibition of NOD signaling pathway. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2014;57:6897–6918. doi: 10.1021/jm401841p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maisonneuve C, Bertholet S, Philpott DJ, De Gregorio E. Unleashing the potential of NOD- and Toll-like agonists as vaccine adjuvants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12294–12299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400478111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burakoff SJ, Ferrara J, Deeg HJ, Atkinson K. Graft-vs.-Host Disease. Marcel Dekker, Inc.; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tada H, Aiba S, Shibata K, Ohteki T, Takada H. Synergistic effect of Nod1 and Nod2 agonists with toll-like receptor agonists on human dendritic cells to generate interleukin-12 and T helper type 1 cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7967–7976. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.7967-7976.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman MK, Midtling EH, Svingen PA, Xiong Y, Bell MP, Tung J, Smyrk T, Egan LJ, Faubion WA., Jr The pathogen recognition receptor NOD2 regulates human FOXP3+ T cell survival. J Immunol. 2010;184:7247–7256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waring P, Mullbacher A. Cell death induced by the Fas/Fas ligand pathway and its role in pathology. Immunology and cell biology. 1999;77:312–317. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1999.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mercier BC, Ventre E, Fogeron ML, Debaud AL, Tomkowiak M, Marvel J, Bonnefoy N. NOD1 cooperates with TLR2 to enhance T cell receptor-mediated activation in CD8 T cells. PloS one. 2012;7:e42170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petterson T, Mansson A, Riesbeck K, Cardell LO. Nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptors and retinoic acid inducible gene-like receptors in human tonsillar T lymphocytes. Immunology. 2011;133:84–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zanello G, Goethel A, Forster K, Geddes K, Philpott DJ, Croitoru K. Nod2 activates NF-kB in CD4+ T cells but its expression is dispensable for T cell-induced colitis. PloS one. 2013;8:e82623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pudla M, Kananurak A, Limposuwan K, Sirisinha S, Utaisincharoen P. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 regulates suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 expression in Burkholderia pseudomallei-infected mouse macrophage cell line RAW 264.7. Innate immunity. 2011;17:532–540. doi: 10.1177/1753425910385484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenstiel P, Till A, Schreiber S. NOD-like receptors and human diseases. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:648–657. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HJ, Yang JS, Woo SS, Kim SK, Yun CH, Kim KK, Han SH. Lipoteichoic acid and muramyl dipeptide synergistically induce maturation of human dendritic cells and concurrent expression of proinflammatory cytokines. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:983–989. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0906588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw MH, Reimer T, Sanchez-Valdepenas C, Warner N, Kim YG, Fresno M, Nunez G. T cell-intrinsic role of Nod2 in promoting type 1 immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1267–1274. doi: 10.1038/ni.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouskra D, Brezillon C, Berard M, Werts C, Varona R, Boneca IG, Eberl G. Lymphoid tissue genesis induced by commensals through NOD1 regulates intestinal homeostasis. Nature. 2008;456:507–510. doi: 10.1038/nature07450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petnicki-Ocwieja T, Hrncir T, Liu YJ, Biswas A, Hudcovic T, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, Kobayashi KS. Nod2 is required for the regulation of commensal microbiota in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15813–15818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907722106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clarke TB, Davis KM, Lysenko ES, Zhou AY, Yu Y, Weiser JN. Recognition of peptidoglycan from the microbiota by Nod1 enhances systemic innate immunity. Nat Med. 2010;16:228–231. doi: 10.1038/nm.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinic MM, Caminschi I, O'Keeffe M, Thinnes TC, Grumont R, Gerondakis S, McKay DB, Nemazee D, Gavin AL. The Bacterial Peptidoglycan-Sensing Molecules NOD1 and NOD2 Promote CD8+ Thymocyte Selection. J Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe T, Kitani A, Murray PJ, Strober W. NOD2 is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 2-mediated T helper type 1 responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:800–808. doi: 10.1038/ni1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe T, Kitani A, Murray PJ, Wakatsuki Y, Fuss IJ, Strober W. Nucleotide binding oligomerization domain 2 deficiency leads to dysregulated TLR2 signaling and induction of antigen-specific colitis. Immunity. 2006;25:473–485. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penack O, Smith OM, Cunningham-Bussel A, Liu X, Rao U, Yim N, Na IK, Holland AM, Ghosh A, Lu SX, Jenq RR, Liu C, Murphy GF, Brandl K, van den Brink MR. NOD2 regulates hematopoietic cell function during graft-versus-host disease. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2101–2110. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchenko ND, Zaika A, Moll UM. Death signal-induced localization of p53 protein to mitochondria. A potential role in apoptotic signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16202–16212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mihara M, Erster S, Zaika A, Petrenko O, Chittenden T, Pancoska P, Moll UM. p53 has a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. Molecular cell. 2003;11:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haupt Y, Rowan S, Shaulian E, Vousden KH, Oren M. Induction of apoptosis in HeLa cells by trans-activation-deficient p53. Genes & development. 1995;9:2170–2183. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thornborrow EC, Patel S, Mastropietro AE, Schwartzfarb EM, Manfredi JJ. A conserved intronic response element mediates direct p53-dependent transcriptional activation of both the human and murine bax genes. Oncogene. 2002;21:990–999. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.da Silva Correia J, Miranda Y, Leonard N, Hsu J, Ulevitch RJ. Regulation of Nod1-mediated signaling pathways. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:830–839. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inohara, Chamaillard, McDonald C, Nunez G. NOD-LRR proteins: role in host-microbial interactions and inflammatory disease. Annual review of biochemistry. 2005;74:355–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKinstry KK, Strutt TM, Swain SL. Regulation of CD4+ T-cell contraction during pathogen challenge. Immunol Rev. 2010;236:110–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00921.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strauss L, Bergmann C, Whiteside TL. Human circulating CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ regulatory T cells kill autologous CD8+ but not CD4+ responder cells by Fas-mediated apoptosis. J Immunol. 2009;182:1469–1480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He YW, Bevan MJ. High level expression of CD43 inhibits T cell receptor/CD3-mediated apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1903–1908. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yokosuka T, Kobayashi W, Takamatsu M, Sakata-Sogawa K, Zeng H, Hashimoto-Tane A, Yagita H, Tokunaga M, Saito T. Spatiotemporal basis of CTLA-4 costimulatory molecule-mediated negative regulation of T cell activation. Immunity. 2010;33:326–339. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walunas TL, Lenschow DJ, Bakker CY, Linsley PS, Freeman GJ, Green JM, Thompson CB, Bluestone JA. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity. 1994;1:405–413. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wing K, Yamaguchi T, Sakaguchi S. Cell-autonomous and -non-autonomous roles of CTLA-4 in immune regulation. Trends in immunology. 2011;32:428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eroglu M, Derry WB. Your neighbours matter - non-autonomous control of apoptosis in development and disease. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:1110–1118. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herman AC, Monlish DA, Romine MP, Bhatt ST, Zippel S, Schuettpelz LG. Systemic TLR2 agonist exposure regulates hematopoietic stem cells via cell-autonomous and cell-non-autonomous mechanisms. Blood cancer journal. 2016;6:e437. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L, Liu Y, Beier UH, Han R, Bhatti TR, Akimova T, Hancock WW. Foxp3+ T-regulatory cells require DNA methyltransferase 1 expression to prevent development of lethal autoimmunity. Blood. 2013;121:3631–3639. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-451765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L, Liu Y, Han R, Beier UH, Bhatti TR, Akimova T, Greene MI, Hiebert SW, Hancock WW. FOXP3+ regulatory T cell development and function require histone/protein deacetylase 3. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1111–1123. doi: 10.1172/JCI77088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holler E, Rogler G, Brenmoehl J, Hahn J, Herfarth H, Greinix H, Dickinson AM, Socie G, Wolff D, Fischer G, Jackson G, Rocha V, Steiner B, Eissner G, Marienhagen J, Schoelmerich J, Andreesen R. Prognostic significance of NOD2/CARD15 variants in HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: effect on long-term outcome is confirmed in 2 independent cohorts and may be modulated by the type of gastrointestinal decontamination. Blood. 2006;107:4189–4193. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holler E, Rogler G, Herfarth H, Brenmoehl J, Wild PJ, Hahn J, Eissner G, Scholmerich J, Andreesen R. Both donor and recipient NOD2/CARD15 mutations associate with transplant-related mortality and GvHD following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2004;104:889–894. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elmaagacli AH, Koldehoff M, Hindahl H, Steckel NK, Trenschel R, Peceny R, Ottinger H, Rath PM, Ross RS, Roggendorf M, Grosse-Wilde H, Beelen DW. Mutations in innate immune system NOD2/CARD 15 and TLR-4 (Thr399Ile) genes influence the risk for severe acute graft-versus-host disease in patients who underwent an allogeneic transplantation. Transplantation. 2006;81:247–254. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000188671.94646.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor PA, Lees CJ, Blazar BR. The infusion of ex vivo activated and expanded CD4(+)CD25(+) immune regulatory cells inhibits graft-versus-host disease lethality. Blood. 2002;99:3493–3499. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoffmann P, Ermann J, Edinger M, Fathman CG, Strober S. Donor-type CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells suppress lethal acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Exp Med. 2002;196:389–399. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen JL, Trenado A, Vasey D, Klatzmann D, Salomon BL. CD4(+)CD25(+) immunoregulatory T Cells: new therapeutics for graft-versus-host disease. J Exp Med. 2002;196:401–406. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.