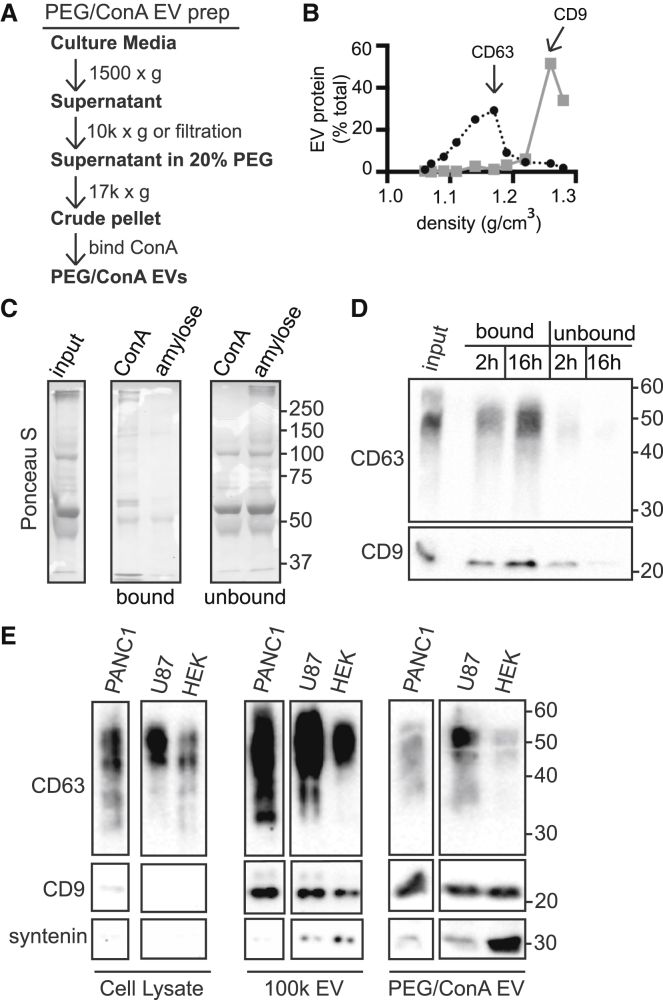

Figure 2.

Comparison of EV collection by PEG/ConA and ultracentrifugation methods. (A) Flow chart of the PEG/ConA EV collection procedure. (B) Sucrose density gradient analysis of HEK293 cell EVs precipitated with PEG. As in Fig. 1D, the x axis indicates the density of each fraction as determined by refractometry. Fractions were immunoblotted for CD63 (black line) and CD9 (gray line) and quantitated, and the values were plotted as the percent of total signal across all fractions. (C) SDS-PAGE of PEG precipitated protein binding to ConA sepharose versus control amylose resin. Ponceau S stain shows the total protein in input, bound, and unbound fractions. (D) PEG precipitated EVs from HEK293 cells were incubated with ConA sepharose for the indicated time, released from beads by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and immunoblotted for CD63 and CD9. (E) Comparison of 100k and PEG/ConA EVs. EVs released by the indicated cell lines over 24 h were harvested from culture media by ultracentrifugation (100k EV) or PEG/ConA precipitation (PEG/ConA EV). 100k EVs from 20% and PEG/ConA EVs from 10% of the cell culture media were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for CD63, CD9, and syntenin. Whole-cell lysate blots were loaded with 10 μg of total protein. The images shown are from a single exposure and were spliced to remove an irrelevant lane. Lighter exposure (not shown) of 100k EV fractions confirmed that U87 cells released the most CD63.