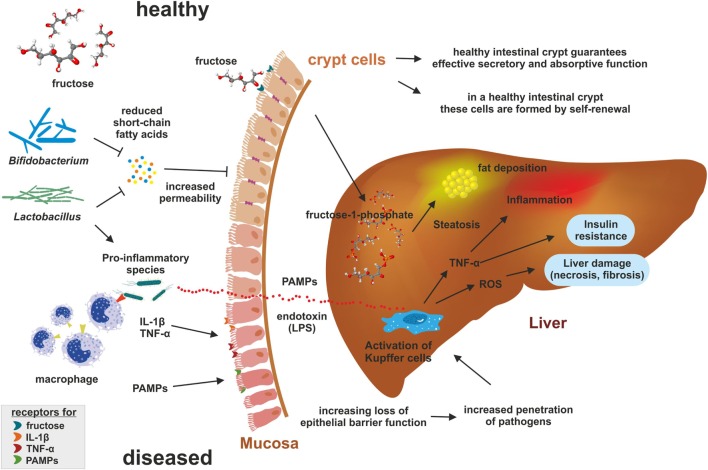

Figure 1.

Impact of fructose on microbiome. Under healthy conditions, the intestine is organized into large numbers of self-renewing crypt-villus units guaranteeing effective secretory and absorptive functions. Elevated concentrations of fructose favor pro-inflammatory microbiota producing endotoxins and suppressing production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) that are essential for intestinal barrier function. Pro-inflammatory microbiota and their products [i.e., lipopolysaccharide (LPS); pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)] recruit macrophages and bind to toll-like receptors (e.g., TLR4) leading to the release of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) causing mucosal inflammation. Subsequently, inflammation decreases expression of tight junction proteins resulting in a higher permeability of the gut barrier. In addition, endotoxins enter the leaky barrier leading to epithelial disruption and increase penetration of pathogens into the blood stream. Reaching the liver, endotoxins increase inflammation by activation Kupffer cells through binding to TLR4 and formation of reactive oxygen (ROS). The formed radicals induce hepatic damage and fibrosis. Furthermore, in the liver the fructokinase generate fructose-1-phosphate from fructose that is degraded into products providing substrate for de novo lipogenesis promoting steatosis.