Abstract

Background and Purpose

Obesity is associated with structural and functional changes in perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT), favouring release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), vasoconstrictor and proinflammatory factors. The cytokine TNF‐α induces vascular dysfunction and is produced by PVAT. We tested the hypothesis that obesity‐associated PVAT dysfunction was mediated by augmented mitochondrial ROS (mROS) generation due to increased TNF‐α production in this tissue.

Experimental Approach

C57Bl/6J and TNF‐α receptor‐deficient mice received control or high fat diet (HFD) for 18 weeks. We used pharmacological tools to determine the participation of mROS in PVAT dysfunction. Superoxide anion (O2 .‐) and H2O2 were assayed in PVAT and aortic rings were used to assess vascular function.

Key Results

Aortae from HFD‐fed obese mice displayed increased contractions to phenylephrine and loss of PVAT anti‐contractile effect. Inactivation of O2 .‐, dismutation of mitochondria‐derived H2O2, uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation and Rho kinase inhibition, decreased phenylephrine‐induced contractions in aortae with PVAT from HFD‐fed mice. O2 .‐ and H2O2 were increased in PVAT from HFD‐fed mice. Mitochondrial respiration analysis revealed decreased O2 consumption rates in PVAT from HFD‐fed mice. TNF‐α inhibition reduced H2O2 levels in PVAT from HFD‐fed mice. PVAT dysfunction, i.e. increased contraction to phenylephrine in PVAT‐intact aortae, was not observed in HFD‐obese mice lacking TNF‐α receptors. Generation of H2O2 was prevented in PVAT from TNF‐α receptor deficient obese mice.

Conclusion and Implications

TNF‐α‐induced mitochondrial oxidative stress is a key and novel mechanism involved in obesity‐associated PVAT dysfunction. These findings elucidate molecular mechanisms whereby oxidative stress in PVAT could affect vascular function.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on Molecular Mechanisms Regulating Perivascular Adipose Tissue – Potential Pharmacological Targets? To view the other articles in this section visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.v174.20/issuetoc

Abbreviations

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- CCCP

carbonyl cyanide m‐chlorophenyl hydrazine

- HFD

high‐fat diet

- mROS

mitochondrial ROS

- PVAT

perivascular adipose tissue

- UCP‐1

uncoupling protein 1

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| Other protein targets a |

| TNF‐α |

| Enzymes b |

| Rho kinase |

| Transporters c |

| UCP1, uncoupling protein‐1, SLC25A7 |

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| H2O2 |

| Infliximab |

| Phenylephrine |

| Y27632 |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article that are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Southan et al., 2016), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 (a,b,cAlexander et al., 2015a,b,c).

Introduction

The perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) releases a wide range of adipokines, vasoactive and inflammatory mediators that influence vascular function in a paracrine manner (Gollasch and Dubrovska, 2004; Szasz et al., 2013). Obesity is frequently associated with structural and functional alterations in PVAT, leading to dysfunction of vascular endothelium and smooth muscle, and increased overall cardiovascular risk. The proposed mechanisms include impaired anti‐contractile function, perivascular inflammation via production of pro‐inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and the accumulation of macrophages, as well as dysregulation of adipocyte‐derived adipokines (Guzik et al., 2007; Ketonen et al., 2010; Fernández‐Alfonso et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2013). TNF‐α, which plays a critical role in the development of vascular dysfunction, insulin resistance, inflammation and atherosclerosis, is produced by the PVAT (Omar et al., 2014; Virdis et al., 2015; da Costa et al., 2016). TNF‐α also induces adipocyte dysfunction, leading to a vicious circle between adipocytes and macrophages, which may aggravate inflammatory changes in PVAT (Takaoka et al., 2010; Oriowo, 2015). Therefore, TNF‐α‐induced PVAT dysfunction may represent a major mechanism whereby this cytokine exerts a deleterious role on vascular function.

The structural and physiological characteristics of PVAT vary in each vascular territory. In the mesenteric bed, PVAT resembles the white adipose tissue showing less differentiated adipocytes with low vascularization and metabolism (Fitzgibbons et al., 2011). However, the morphological characteristics of aortic PVAT are very similar to that of brown adipose tissue (BAT), with small, multilocular lipid droplets and abundant mitochondria in the adipocytes. The similarities extend to the transcriptional profile as well, with close gene expression overlapping between BAT and PVAT, including expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP‐1), important in thermogenesis (Fitzgibbons et al., 2011; Padilla et al., 2013). Increased thermogenic activity of PVAT is associated with improved endothelial function and protection from vascular disease, which implies that PVAT itself may influence thermogenesis, with immediate translation into vascular activity (Chang et al., 2012).

Mitochondria are critical regulators of cell death, calcium signalling, generation and disposal of ROS. We have recently shown that ROS generated from the mitochondrial metabolism mediates PVAT anti‐contractile effects (Costa et al., 2016). Consistent with this concept, mitochondrial dysfunction in adipocytes of obese patients increases pro‐oxidative status via generation of ROS, thereby compromising tissue homeostasis (Medina‐Gomez, 2012). Whether mitochondrial ROS (mROS) in the PVAT leads to loss of its modulatory effects on the vasculature is unclear. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that obesity induced by a high‐fat diet (HFD) impaired mitochondrial function in the PVAT, leading to increased generation of mROS and loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT. We also determined the specific role of TNF‐α on mROS generation in PVAT from obese animals.

Methods

Animals and diets

All animal care and experimental protocols were performed in accordance with the Conselho Nacional de Controle de Experimentação Animal and were approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use of the University of Sao Paulo, Ribeirao Preto, Brazil (Protocol no. 149/2014). Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath and Lilley, 2015).

Five‐week‐old, male, C57Bl/6 J and TNF‐α receptor‐deficient mice (TNF KO) were obtained from the Laboratory of Molecular Immunology and Embryology, Transgenose Institute, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Orléans, France, and maintained in the Animal Facility of the University of Sao Paulo, Ribeirao Preto, Brazil, on 12 h light/dark cycles under controlled temperature (22 ± 1°C) with ad libitum access to food and water. After a 1 week acclimatization period, mice were divided into two groups: 1) mice maintained on a control diet (protein 22%, carbohydrate 70% and fat 8% of energy, PragSolucoes, Jau, Brazil); 2) mice receiving an HFD (protein 10%, carbohydrate 25% and fat 65% of energy, PragSolucoes) for 18 weeks. After the treatment period, mice were killed by carbon dioxide (CO2) inhalation.

Nutritional and metabolic profile of high‐fat diet‐induced obese mice

The nutritional profile of the animals was determined weekly by analysis of the caloric intake, feed efficiency, body weight and body fat. Caloric intake (per mouse) was calculated from the weekly food intake multiplied by the dietary energetic value. Feeding efficiency and the ability to transform consumed calories into body weight were determined with the formula: mean body weight gain (g)/total calorie intake. Animal body weight was measured weekly and obesity was defined using the adiposity index {[body fat (g)/final body weight (g)] × 100}. Body fat was calculated by the sum of the epididymal, retroperitoneal and visceral fats (Taylor and Phillips, 1996). After 18 weeks of HFD, glucose concentrations were determined in serum samples from mice fasted for 12 h, by an enzymic colorimetric glucose oxidase method (Doles®).

Assessment of vascular function

The thoracic aorta was rapidly removed, transferred to an ice‐cold (4°C) modified Krebs‐Henseleit solution (composition in mM: 130 NaCl, 14.9 NaHCO3, 4.7 KCl, 1.18 KH2PO4, 1.17 MgSO4·, 5.5 glucose, 1.56 CaCl2·and 0.026 EDTA) gassed with 5% CO2: 95% O2 to maintain a pH of 7.4 and dissected into 2 mm rings whereby perivascular fat and connective tissues were either removed (PVAT−) or left intact (PVAT+). Aortic rings were mounted in a wire myograph to measure isometric tension, as previously described (Lobato et al., 2012). Vessels were allowed to equilibrate for about 30 min in the Krebs‐Henseleit solution. After the stabilization period, endothelial function was assessed by testing the relaxant effect of ACh (10−6 M) on vessels contracted with phenylephrine (10−7 M). Aortic rings exhibiting a vasodilator response to ACh greater than 80% were considered endothelium‐intact vessels. In experiments with endothelium‐denuded vessels, aortic rings were subjected to rubbing of the intimal surface. Rings showing a maximum of 5% relaxation in response to ACh were considered to be without endothelium. Cumulative concentration–response curves to phenylephrine (10−10–10−4 M) and the Rho kinase inhibitor Y27632 (10−10–10−4 M) were performed in PVAT+ or PVAT− aortic rings.

Contractile responses to phenylephrine were also determined after incubation with the selective superoxide anion (O2 .‐) scavenger tiron (10−4 M), the mitochondrial uncoupler, carbonyl cyanide m‐chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP, 10−6 M), Y27632 (10−4 M) or the antioxidants MnTMPyP (3 × 10−5 M) and PEG‐catalase (200 U·mL−1), 30–40 min before adding the contractile agonist. Each vascular preparation was tested with a single agent.

Measurement of ROS in PVAT

Dihydroethidium

ROS generation in PVAT was assessed by dihydroethidium (DHE), as previously described (Suzuki et al., 1995). Aortas surrounded by periaortic fat were embedded in medium for frozen tissue specimens to ensure optimal cutting temperature (OCT™) and stored at −80°C. Fresh‐frozen specimens were cross sectioned at 10 μm thickness and placed on slides covered with poly‐(L‐lysine) solution. The tissue was loaded with DHE, a non‐selective dye for ROS detection (5 × 10−6 M; 30 min at 37°C), which was prepared in phosphate buffer (0.1 M). Images were collected on a Zeiss microscope and analysed by measuring the mean optical density of the fluorescence in a computer system (Image J software) and normalized by the area. Results are expressed as fold changes, relative to the control.

Amplex red

PVAT isolated from aorta was incubated in Krebs Henseleit solution in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of CCCP (0.5 × 10−6–4 × 10−6 M). After this period, PVAT was frozen in Krebs, macerated and centrifuged. A total of 50 μL aliquots of the supernatant were removed, and the amount of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) produced by PVAT was determined fluorometrically by measuring the conversion of Amplex Red (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (8 × 10−6 M) to a highly fluorescent compound resorufin (Zhou et al., 1997), in the presence of horseradish peroxidase (4 U·mL−1). Resorufin fluorescence measured with a plate fluorimeter (Synergy™ 2 Multi‐Detection Microplate Reader, BioTek Instruments) using excitation and emission wavelengths of 530 and 590 nm respectively. The fluorescence values were expressed per total amount of tissue proteins.

Lucigenin

PVAT ROS generation was measured by a luminescence assay using lucigenin as the electron acceptor and NADH as the substrate. Periaortic fat from control and obese mice was homogenized in assay buffer (50 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM EGTA and 150 mM sucrose, pH 7.4) with a glass‐to‐glass homogenizer. The assay was performed with 100 μL of sample, lucigenin (5 μM), NADH (0.1 mM) and assay buffer. Luminescence was measured for 30 cycles of 18 s each by a luminometer (Lumistar Galaxy, BMG Labtechnologies, Ortenberg, Germany). Basal readings were obtained prior to the addition of NADH, and the reaction was started by the addition of the substrate. Basal and buffer blank values were subtracted from the NADH‐derived luminescence. Superoxide anion (O2 .‐) was expressed as relative luminescence units·mg−1 of protein.

Determination of superoxide dismutase and catalase activity in PVAT

PVAT was isolated from thoracic aorta, homogenized in 300 μL PBS (pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 5000 x g (15 min, 4°C). The supernatant was used to analyse superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity (SigmaAldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

PVAT catalase activity was assayed by H2O2 consumption. PVAT was homogenized in PBS as previously described (Gonzaga et al., 2014). Reaction buffer was added to quartz cuvettes containing 20 μL of the supernatant. The absorbance was read for 1 min at 240 nm. One catalase unit (U) was defined as the amount of enzyme required to decompose 1 μmol of H2O2·min−1.

Mitochondrial respiration in PVAT

Respiratory parameters were studied in situ in saponin‐permeabilized PVAT isolated from control and obese mice. Freshly excised PVAT was placed into ice‐cold biopsy preservation solution (BIOPS; composition: 2.7 mM EGTA, 20 mM imidazole, 20 mM taurine; 50 mM potassium 2‐(N‐morpholino) ethanesulfonate, 0.5 mM DTT, 6.5 mM MgCl2, 15 mM phosphocreatine; 0.57 mM ATP, pH 7.1). For permeabilization, tissue was placed into BIOPS solution containing saponin (0.01%) for 5 min and was washed in BSA solution (0.1%) for 5 min under agitation. Permeabilized tissues were rinsed with mitochondrial respiration media MiR05 (0.5 mM EGTA, 3 mM MgCl2, 60 mM K‐lactobionate, 20 mM taurine, 10 mM KH2PO4, 20 mM HEPES, 110 mM sucrose, 1 g·L−1 albumin, pH 7.1). PVAT respiration was monitored in MiR05 solution containing respiratory substrates (5.2 mM succinate, 4.5 mM pyruvate, 2.5 mM malate and 2.5 mM glutamate) at 37°C using the OROBOROS High Resolution Oxygraph (Austria) equipped with the DataLab 5.0 software (Dechandt, et al., 2016).

Quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from PVAT using Trizol® (Invitrogen). RNA was treated with DNAse I (1 U·μL−1, Promega) and used for first‐strand cDNA synthesis, accordingly to the manufacturer instructions. mRNA levels were quantified in triplicate by qPCR StepOnePlus™ Life Technologies. Specific primers (TaqMan™) for RT‐qPCR were as follows: mouse TNF [Mm00443260_g1] and β‐actin [Mm00607939_s1], purchased from Life Technologies. PCR cycling conditions included 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min and 72°C for 60 s. Dissociation curve analysis confirmed that signals corresponded to unique amplicons. Specific mRNA expression levels were normalized relative to β‐actin mRNA levels using the comparative 2‐ΔΔCt method.

Western blot analysis

PVAT isolated from aortas was frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in a lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 μg·mL−1 leupeptin, 1 μg·mL−1 pepstatin, 1 μg·mL−1 aprotinin, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF and 1 mM sodium fluoride). The tissue extracts were centrifuged, and total protein content was quantified using the Bradford method (Bradford, 1976). Proteins (60 μg) were separated by electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred on to nitrocellulose membranes. Non‐specific binding sites were blocked with 5% BSA in TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (for 1 h at 24°C). Membranes were incubated with antibodies (at the indicated dilutions) overnight at 4°C. Antibodies were used as follows: anti‐MnSOD (1:1000 dilution; Millipore), anti‐catalase (1:500 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology), anti‐MYPT‐1 (1:400 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology), anti‐pMYPT‐1 Thr853 (1:400 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology) anti‐UCP‐1 (1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology) and anti‐β‐actin (1:3000 dilution; Abcam). After incubation with secondary antibodies, signals were obtained by chemiluminescence, visualized by autoradiography and quantified densitometrically.

Assessment of Rho kinase activity

Rho kinase activity was determined by elisa with a Rho kinase activity assay kit (Cell Biolabs).

Data and statistical analyses

The data and statistical analysis in this study comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015). Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n represents the number of animals used. Contractions to phenylephrine are expressed as tension changes (mN) in the displacement from baseline. The individual concentration–response curves were fitted into a curve by nonlinear regression analysis. pD2 (defined as the negative logarithm of the EC50 values) and maximal response (Emax) were compared by Student's t‐test or two‐way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test, as appropriate. The Prism software, version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), was used to analyse these parameters as well as to fit the sigmoidal curves. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Materials

Phenylephrine, ACh, Y27632, PEG‐catalase, MnTMPyP and tiron were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (St. Louis, MO). CCCP and recombinant TNF‐α were purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). Infliximab (Remicade ®) was purchased from Janssen Biologics.

Results

Increased ROS generation in PVAT from obese mice impairs PVAT modulation of vascular contraction

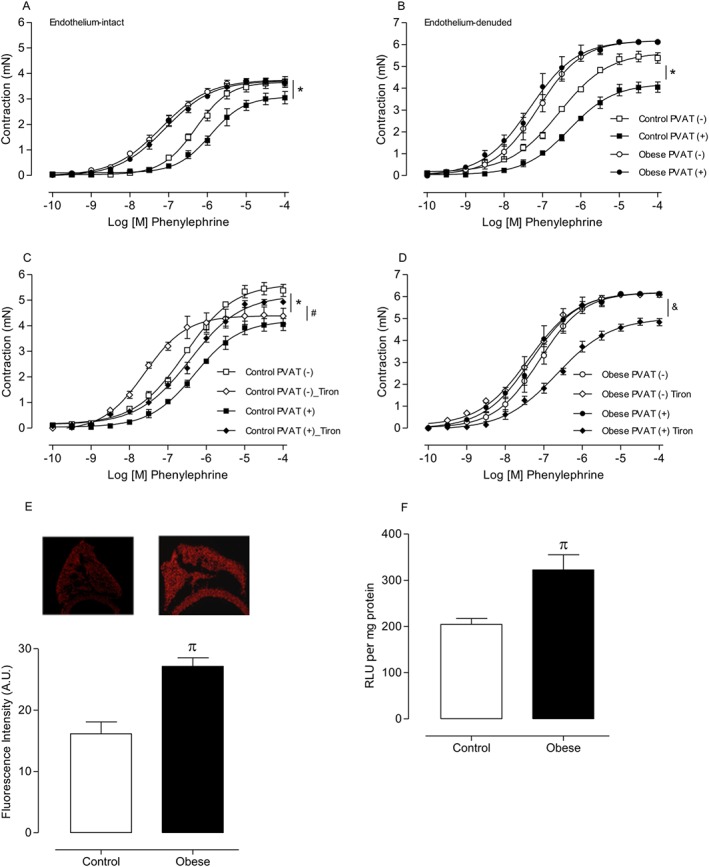

After 18 weeks on the HFD, there was a marked increase in nutritional and anthropometric parameters in the obese mice, compared with mice on the control diet (Table S1). To investigate whether HFD‐induced obesity impaired modulation of aortic contractions by PVAT, aortic rings with or without PVAT were exposed to the vasoconstrictor phenylephrine in a concentration‐dependent manner. Aortic rings with PVAT from HFD‐fed mice displayed higher maximal contractions and increased pD2 values to phenylephrine, compared with rings from control mice (Figure 1A, Table S3). Removal of PVAT increased contractions to phenylephrine only in control mice and resulted in maximal contractions that were not significantly different between the groups (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Increased superoxide anion generation contributes to the loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT in HFD obesity. Concentration–effect curves to phenylephrine (PE) were performed in endothelium‐intact [(A) n = 6 for each experimental group] and endothelium‐denuded [(B) n = 7 for each experimental group] aortic rings with or without PVAT. The role of ROS on PVAT modulation of aortic smooth muscle contraction was investigated using tiron (10−4 M), an O2 .‐ scavenger in endothelium‐denuded aortic rings from control [(C) n = 7 for each experimental group] and obese [(D) n = 7 for each experimental group] mice. ROS generation in PVAT was measured ( E) by DHE and (F) by lucigenin (n = 8 in all groups) in control and obese mice. Results represent the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05 versus Control PVAT (−); # P < 0.05 versus Control PVAT (+); & P < 0.05 versus Obese PVAT (+); π P < 0.05 versus Control.

To investigate whether increased contractions to phenylephrine in PVAT‐intact aortas of HFD‐fed mice were due to reduced release of endothelium‐dependent relaxing factors, responses to phenylephrine were also induced in endothelium‐denuded (with or without PVAT) aortic rings. Absence of the endothelium increased contractions to phenylephrine . However, aortic rings with PVAT from HFD‐fed mice still exhibited increased phenylephrine‐induced contractions when compared with the control group (Figure 1B), suggesting that the loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT in obesity is for the most part endothelium‐independent.

We next determined whether increased ROS generation in PVAT directly mediated the effects of HFD on the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT. Inactivation of O2 .‐ by the superoxide scavenger tiron (10−4 M) significantly decreased phenylephrine‐induced contractions in PVAT (−) aortic rings from control mice, whereas contractile responses in PVAT (+) rings were increased (Figure 1C). Tiron decreased phenylephrine‐induced contractions in PVAT (+) aortic rings from HFD‐fed mice (Figure 1D). These findings suggest that obesity induces a significant increase in ROS generation that contributes to the loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT. Consistent with these observations, basal levels of ROS, determined by DHE fluorescence intensity (Figure 1E) and lucigenin‐derived luminescence (Figure 1F), were significantly increased in PVAT from HFD‐fed mice compared with PVAT from control animals.

Mitochondria‐derived ROS in PVAT mediate the increased phenylephrine‐induced vasoconstriction in obese mice

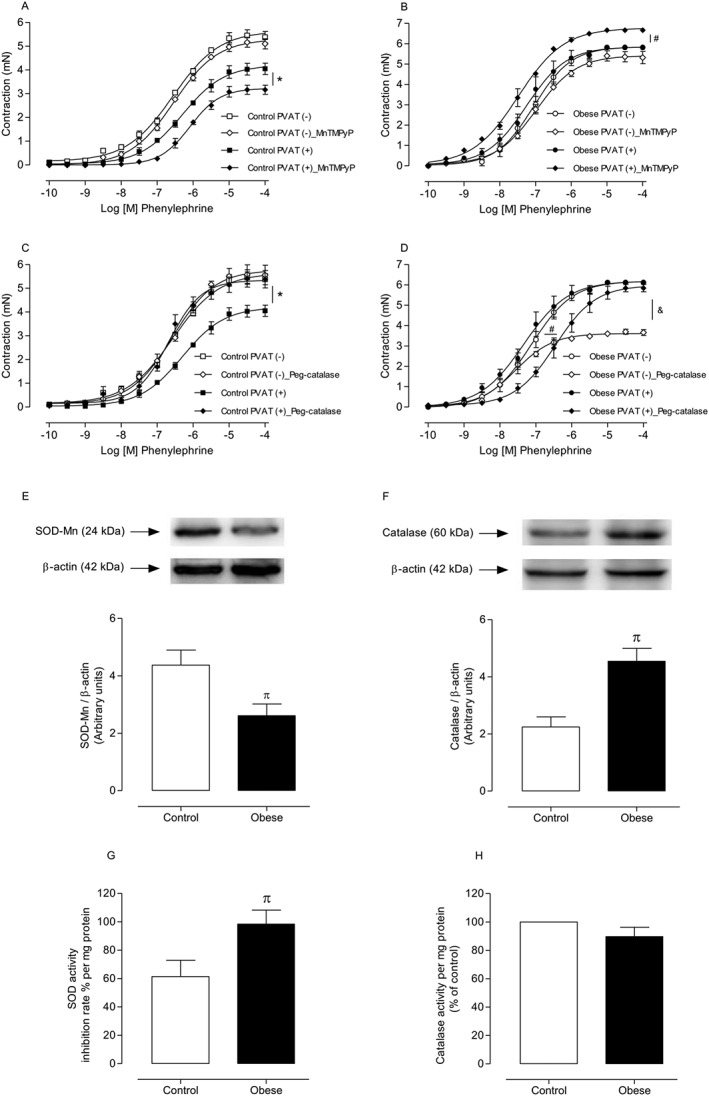

In order to assess whether obesity impaired mitochondrial function and increased O2 ·‐ production in PVAT, we used the membrane permeant Mn‐SOD mimetic MnTMPyP (3 × 10−5 M) (Liang et al., 2009). PVAT (+) aortic rings from control mice displayed decreased contractile response to phenylephrine in the presence of MnTMPyP (Figure 2A), confirming that mitochondrial O2 ·‐ mediates regulation of vascular contraction by PVAT. In PVAT (+) aortic rings from obese mice, the O2 ·‐ scavenger significantly increased contractile responses to phenylephrine, which is consistent with SOD‐mediated dismutation of the increased endogenous O2 ·‐ to generate H2O2 (Figure 2B). Indeed, the presence of PEG‐catalase(200 U·mL−1), which is rapidly transported to the intracellular space and participates in the dismutation of mitochondria‐derived H2O2, increased the contractile response to phenylephrine in PVAT (+) aortae from control mice (Figure 2C). By contrast, PVAT (−) and PVAT (+) aortic rings from obese mice displayed decreased contractile responses to phenylephrine in the presence of PEG‐catalase (Figure 2D), suggesting that H2O2 is a contractile factor in obesity. Consistent with the idea that PVAT‐derived ROS modulate vascular reactivity, expression of the Mn‐SOD isoform was significantly reduced (Figure 2E) whereas catalase expression was increased in PVAT from obese mice (Figure 2F). Obesity increased SOD activity (Figure 2G) but did not change catalase activity (Figure 2H) in PVAT. These data suggest a compensatory mechanism for increased ROS in PVAT from obese mice.

Figure 2.

Mitochondria are a potential source of increased ROS in PVAT from obese mice, and mitochondria‐derived ROS alter the expression of antioxidant enzymes in PVAT. Concentration–effect curves to PE were performed in endothelium‐denuded aortic rings from control [(A and C) n = 8 for each experimental group] and obese [(B and D) n = 8 for each experimental group] mice. The role of mROS on PVAT modulation of aortic smooth muscle contraction was investigated using MnTMPyP (3 × 10−5 M), a mitochondria‐targeted superoxide scavenger and PEG‐catalase (Peg‐cat; 200 U·mL−1), which dismutates mitochondria‐derived H2O2. Protein expression and activity of the antioxidant enzymes SOD‐Mn [(E and G) n = 5 in both groups] and catalase [(F and H) n = 5 in both groups] were determined by Western blot and SOD‐Mn and catalase activity assay kits, respectively, in PVAT from control and obese mice. Representative Western blots are shown in the upper panels, with quantitative analysis in the lower panels. Results were normalized to β‐actin expression and are expressed as relative units. Results represent the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05 versus Control PVAT (+); # P < 0.05 versus Obese PVAT (+); & P < 0.05 versus Obese PVAT (−); π P < 0.05 versus Control.

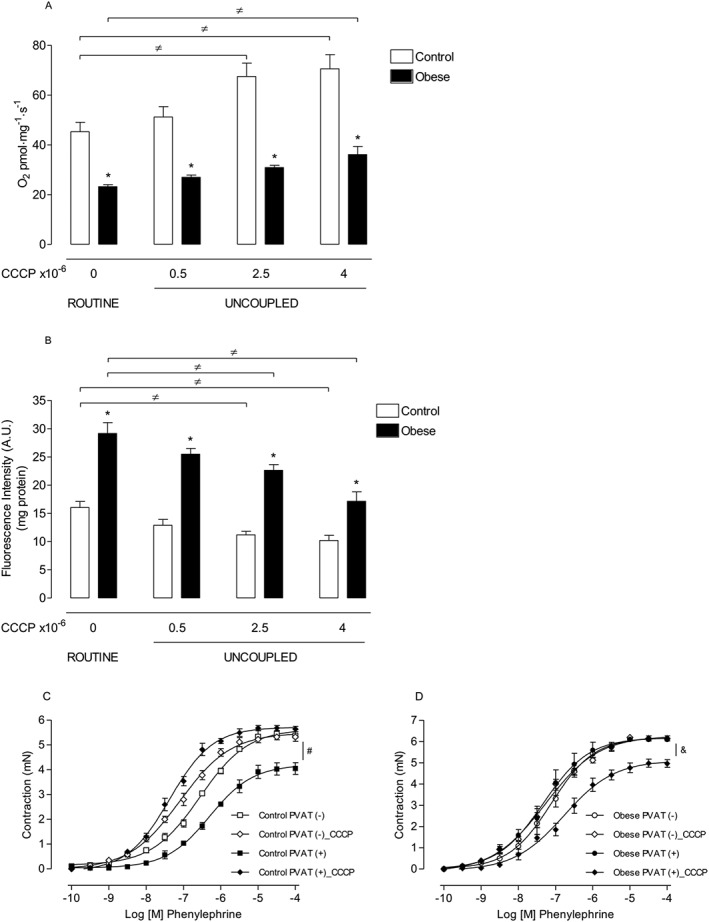

Impaired mitochondrial function mediates the increased ROS generation and loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT in HFD‐treated obese mice

We examined whether mitochondrial coupling, in turn, promotes ROS generation and the subsequent loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT in HFD‐fed mice. Analysis of mitochondrial respiration in PVAT from HFD‐fed mice revealed a severe decrease in O2 consumption rates in both ROUTINE (when the rate depends on cellular ATP demand) and UNCOUPLED (when the maximum capacity of electron transport system is stimulated by increasing concentrations of the protonophore CCCP) states of ATP synthase, when compared with that in control animals (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

HFD obesity increases mitochondria‐derived O2 .‐ conversion to H2O2, which contributes to the loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT. Mitochondrial oxygen consumption (A) and (B) H2O2 production (n = 9 in all groups) in PVAT from the thoracic aorta of control and obese animals in the presence of ROUTINE and increasing concentrations of CCCP, a protonophore and mitochondrial uncoupler. Concentration–effect curves to phenylephrine were performed in endothelium‐denuded aortic rings from control (C; n = 6 for each experimental group) and obese (D; n = 7 for each experimental group) mice. The role of mROS generation on PVAT modulation of aortic smooth muscle contraction was investigated using CCCP (10−6 M). Results represent the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05 versus respective Control; ≠ P < 0.05 versus respective ROUTINE; # P < 0.05 versus Control PVAT (+); & P < 0.05 versus Obese PVAT (+).

Under the ROUTINE conditions, PVAT from the thoracic aorta of obese animals showed a significant increase in H2O2 production, measured using Amplex Red, when compared with control animals. Increasing concentrations of CCCP, which accelerates electron transport rates into respiratory chain and decreases the lifetime of intermediates capable of donating electrons towards O2 ·‐ formation (Skulachev, 1998), gradually reduced H2O2 levels in PVAT of both groups of mice. However, in PVAT from obese mice, the additional increase in mitochondrial uncoupling led H2O2 production to the levels observed in the control group in the absence of the uncoupler (Figure 3B).

Because a reduction in O2 consumption rate increases the formation of ROS through the mitochondrial respiratory chain, we further investigated the potential contribution of mitochondria‐derived H2O2 on vascular dysfunction in obese mice. Vascular reactivity studies demonstrated a significant increase in contractile responses mediated by phenylephrine in CCCP‐treated PVAT (+) vessels from control animals (Figure 3C), which suggests that basal ROS generation in mitochondria mediates the anti‐contractile effects evoked by PVAT. In contrast to the effect of CCCP in control animals, the increased contraction to phenylephrine in PVAT (+) aortic rings from HFD‐fed mice was extensively restored by the protonophore CCCP (10−6 M) (Figure 3D). Together, these results indicate that impairment of mitochondrial respiration in obesity increases ROS generation in PVAT and leads to loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT.

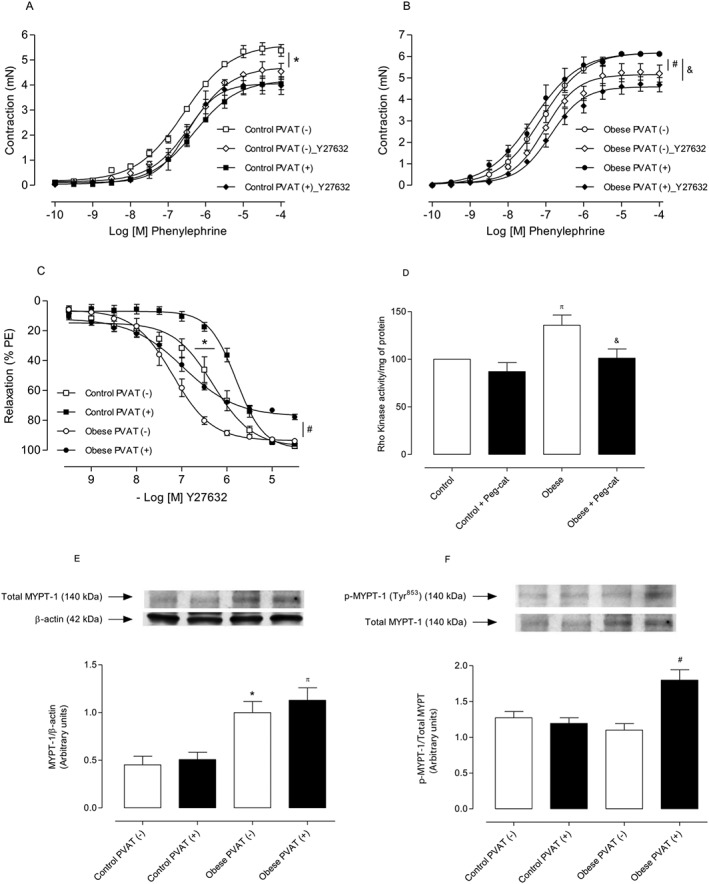

Loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT in HFD‐induced obesity is mediated by increased activity of the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway in vascular smooth muscle

The RhoA/Rho kinase pathway plays a critical role in vascular smooth muscle contraction and calcium (Ca2+) sensitization and contributes to the vascular hyperactivity in obesity and hypertension. We examined whether increased mROS in the PVAT induces RhoA/Rho kinase activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Figure 4A shows that pretreatment of aortic rings with the Rho kinase inhibitor Y‐27632 (10−4 M) decreased contractions to phenylephrine only in PVAT (−) vessels from control mice. However, Y‐27632 corrected the increased vasoconstrictor response to phenylephrine in PVAT (−) and PVAT (+) vessels from obese mice (Figure 4B). These results point to an important role of the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway in mediating the vascular effects of increased mROS generation in PVAT from obese mice.

Figure 4.

Increased mROS in PVAT from obese mice induces RhoA/Rho kinase activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Concentration–effect curves to phenylephrine were performed in endothelium‐denuded aortic rings from control [(A) n = 7 for each experimental group] and obese [(B) n = 8 for each experimental group] mice. The role of RhoA/Rho kinase pathway on PVAT modulation of aortic smooth muscle contraction was investigated using Y27632 (10−4 M). Concentration–effect curves to Y27632 (C) were performed in endothelium‐denuded aortic rings with or without PVAT (n = 8 for each experimental group); Y27632‐induced relaxation was evaluated in phenylephrine (PE)‐contracted vessels. In (D), the Rho kinase activity was determined by elisa in aortas from control and obese mice (n = 5 in both groups). Representative Western blots are shown in the upper panels, with quantitative analysis in the lower panels [(E and F) n = 5 for each experimental group]. Results were normalized to β‐actin expression and are expressed as relative units. Representative images were selected from the same membrane. Results represent the mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05 versus Control PVAT (−); π P < 0.05 versus Control PVAT (+); # P < 0.05 versus Obese PVAT (−); & P < 0.05 versus Obese PVAT (+).

Phenylephrine‐contracted arteries from HFD‐fed mice exhibited an increased sensitivity to Rho kinase inhibition compared with control arteries (Figure 4C). Rho kinase activity was up‐regulated in aortas isolated from obese mice, and PEG‐catalase decreased Rho kinase activity (Figure 4D). Consistent with the increased RhoA/Rho kinase pathway activation, PVAT from obese mice displayed significant increases in both total (Figure 4E) and phosphorylated (Figure 4F) MYPT‐1, a major Rho kinase target.

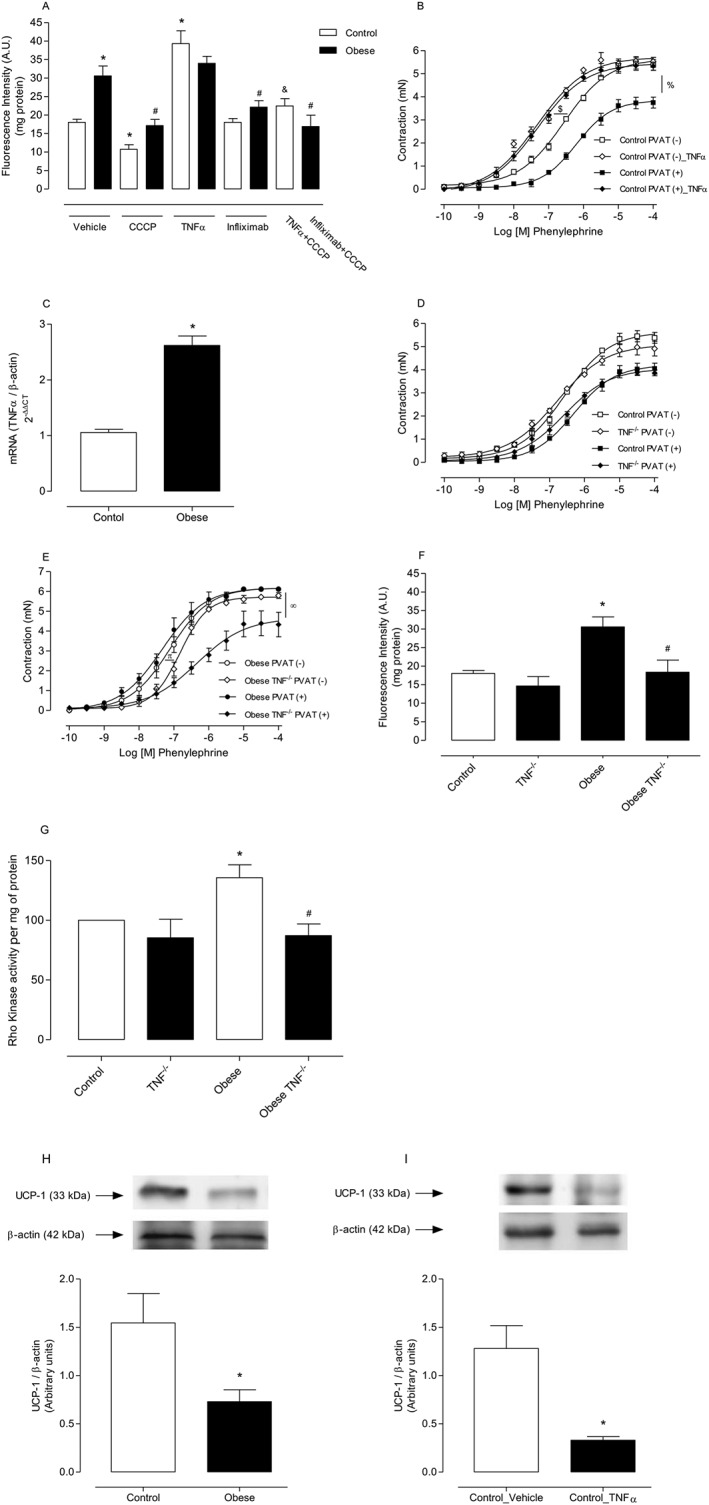

TNF‐α contributes to increased mitochondrial ROS and mediates the loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT in HFD‐fed obese mice

The contribution of TNF‐α, a major mediator of adipose tissue inflammation, to the raised levels of ROS in PVAT from obese mice, was determined. The TNF‐α inhibitor infliximab (10−4 M) effectively reduced mitochondrial H2O2 levels, evaluated by Amplex Red assay, in PVAT from obese mice. Control isotype (anti‐mouse IgG) did not alter PVAT H2O2 production (data not shown). The effects of infliximab were comparable with those evoked by the mitochondrial uncoupler CCCP, and they were not potentiated by concomitant incubation with CCCP, indicating the participation of TNF‐α in the increased mROS generation in PVAT from obese mice. Supporting these data, incubation of PVAT from control animals with TNF‐α (5 ng·mL−1) dramatically increased H2O2 levels, and CCCP attenuated this effect (Figure 5A). Aortic rings from control mice incubated with TNF‐α displayed increased contractile responses to phenylephrine when compared with respective vehicle‐treated control rings. However, the magnitude of this effect was markedly greater in PVAT (+) vessels (Figure 5B), supporting the idea that obesity‐associated inflammation directly affects PVAT and vascular smooth muscle function.

Figure 5.

PVAT‐derived TNF‐α mediates increased mROS generation and is a critical mediator of the loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT in arteries from HFD‐fed obese mice. Production of H2O2 by PVAT (A) was examined in the presence of vehicle, CCCP, infliximab and TNF‐α, using Amplex Red reagent (n = 7 in all groups). Concentration–effect curves to phenylephrine were performed in aortic rings from control mice incubated with TNF‐α (5 ng·mL−1) [(B) n = 8 for each experimental group]. TNF‐α mRNA expression was assessed by real‐time PCR [(C) n = 6 in all groups]. Concentration–effect curves to phenylephrine (PE) were performed in aortic rings from control [(D) n = 8 for each experimental group] and obese [(E) n = 8 for each experimental group] TNF‐α receptor‐deficient mice. Production of H2O2 by PVAT [(F) n = 7 in all groups]. Rho kinase activity was determined by elisa in aortas from wild type and TNF receptor deficient mice [(G) n = 5 in both groups]. UCP‐1 protein expression in PVAT from HFD‐treated mice [(H) n = 6 in both groups] and PVAT from control mice incubated with TNF‐α [(I) n = 6 in both groups] was determined by Western blot. Results represent the mean ± SEM. Representative Western blots are shown in the upper panels, with quantitative analysis in the lower panels. Results were normalized to β‐actin expression and are expressed as relative units. * P < 0.05 versus Control; # P < 0.05 versus Obese; & P < 0.05 versus Control_TNF‐α; $ P < 0.05 versus Control PVAT (−); % P < 0,.05 versus Control PVAT (+); π P < 0.05 versus Obese PVAT (−); ∞ P < 0.05 versus Obese PVAT (+).

Furthermore, PVAT from obese mice exhibited increased TNF‐α mRNA expression, evaluated by quantitative RT‐PCR experiments (Figure 5C).

The potential contribution of TNF‐α to elevated mROS generation in PVAT of obese mice was further examined using TNF‐α receptor deficient mice. As previously mentioned, TNF‐α receptor deficient mice exhibited nutritional parameters similar to those observed in wild type mice (Table S2). However, mice deficient in TNF‐α receptors did not exhibit increased blood glucose. There was no significant difference in vascular responses to phenylephrine between mice lacking TNF‐α receptors and the control group either in the presence or in the absence of PVAT (Figure 5D). However, TNF‐α receptor deficiency in obese mice significantly reduced both the sensitivity and the maximal contraction to phenylephrine in PVAT (−) and PVAT (+) aortic rings (Figure 5E).

After confirming improved PVAT modulation of vascular contraction in obese mice lacking TNF‐α receptors, we examined potential mechanisms underlying this effect by evaluating the generation of H2O2 in PVAT from obese TNF‐α receptor deficient mice. In these animals, there was a significant decrease in H2O2 levels (Figure 5F), indicating that this pro‐inflammatory adipokine is a critical mediator of the loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT in obesity. Rho kinase activity was up‐regulated in aorta isolated from obese mice, and lack of TNF‐α receptor decreased Rho kinase activity (Figure 5G).

As UCP‐1 regulates the mitochondrial redox state, UCP‐1 protein expression was determined in PVAT of obese animals using Western blot analysis. Obesity reduced UCP‐1 protein expression in the PVAT (Figure 5H). Consistent with this finding, incubation of PVAT from control mice with TNF‐α significantly reduced UCP‐1 expression (Figure 5I), further supporting our hypothesis that TNF‐α is a crucial mediator of increased mROS generation in PVAT from obese mice.

Discussion

The present study describes a previously unknown contribution of mitochondria to PVAT‐associated oxidative stress and vascular dysfunction in obesity. HFD‐induced obesity increased O2 .‐ and H2O2 formation in PVAT by reducing mitochondrial respiration, which might have been due to lower expression of the uncoupling protein UCP‐1 and decreased expression of antioxidants, primarily by increasing TNF‐α production in the adipocytes. Importantly, these changes are associated with increased activation of the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells, which further contributes to obesity‐associated vascular dysfunction.

Although most of the published experiments have used mesenteric vessels, the role of aortic PVAT in human vascular disease is becoming increasingly apparent. The Framingham Heart Study recently reported that high levels of thoracic PVAT is significantly associated with a higher prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, even in individuals without high levels of visceral adipose tissue (Britton et al., 2012). Of importance, the activation of thermogenesis in thoracic aorta PVAT is accompanied by attenuation of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E deficient mice (ApoE), whereas this protection is lost in mice where the PVAT is absent (Chang et al., 2012). Clearly, the emerging data from these studies compel us to better understand the effects of aortic PVAT on vascular pathophysiology.

Perivascular fat regulates vascular tone through the release of vasoactive mediators (Löhn et al., 2002; Gollasch and Dubrovska, 2004). Impairment of this ability has detrimental effects on the vascular system. Our data support a defective PVAT modulation of vascular contraction in obesity, as the physiological anti‐contractile properties of PVAT in response to adrenergic stimulation were abolished, leading to higher maximal contractions in obese mice. Our findings are consistent with previous studies showing impaired PVAT‐mediated vasodilation in obese mice (Marchesi et al., 2009) and increased PVAT‐mediated contractile effects in coronary arteries from obese pigs (Owen et al., 2013).

Two main mechanisms mediate the vascular effects of PVAT: an endothelium‐dependent pathway involving release of NO and an endothelium‐independent pathway involving release of H2O2 (Gao et al., 2007; Spradley et al., 2015). Our results indicate impaired regulation of H2O2 production in PVAT from HFD‐treated mice, as a consequence of increased O2 .‐ production. In general, O2 .‐ directly attenuates the biological activity of NO (Gil‐Ortega et al., 2014). However, the short half‐life and limited diffusion of O2 .‐ decreases the possibility that this ROS is the main PVAT‐derived factor controlling vascular function. The more stable metabolite of this free radical, H2O2, has paracrine effects on the vasculature, eliciting both vasoconstriction and vasorelaxation (Gil‐Longo and González‐Vázquez, 2005; Ardanaz and Pagano, 2006). Inactivation of O2 .‐ increased contractions to phenylephrine in PVAT‐intact aortas from control mice, indicating a potential role for O2 .‐‐derived H2O2 on the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT. Conversely, phenylephrine‐induced contractions were significantly lower in PVAT‐intact aortas from HFD‐fed mice in the presence of tiron. Consistent with this finding, ROS generation was substantially increased in PVAT from the thoracic aorta of obese mice, suggesting that H2O2, formed via SOD from O2 .‐, acts as a signalling molecule activating redox‐sensitive pathways, contributing to the loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT. Under conditions of oxidative stress, the body has compensatory mechanisms that decrease or increase local free radical production. This mechanism may explain the absence of antioxidant effects in PVAT‐denuded vessels, indicating that, in the presence of periaortic fat, mitochondria play a major role in ROS production.

Obesity is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, including abnormalities in mitochondrial fission and fusion, impaired mitochondrial biogenesis (Zorzano et al., 2009), inflammation and oxidative stress (Martínez, 2006). Importantly, mitochondrial membrane depolarization, through mROS‐dependent and independent mechanisms, plays a pivotal role in vascular biology. Considering the presence of large numbers of mitochondria and the relatively lower oxygen consumption in PVAT (Greenstein et al., 2009; Fitzgibbons et al., 2011; Chang et al., 2012; Padilla et al., 2013), we hypothesized that the mitochondrial electron transport chain played a key role as the major location of O2 .‐ generation in PVAT, which was then converted to H2O2 by the enzyme SOD. In fact, ROS production in PVAT is controlled by the activity of the mitochondrial electron transport system, which explains the severe decrease in the rate of O2 consumption concurrent with the highest rate of ROS production in PVAT from HFD‐fed mice when compared with that in control animals. When the electron transport system was accelerated in PVAT from obese animals, H2O2 production was reduced to levels observed in the PVAT of control animals, and contractions to phenylephrine in PVAT‐intact vessels from obese mice were restored. Changes in the number of mitochondria may underlie cellular responses related to hypoxia, oxidative stress and apoptosis (Martínez, 2006). However, there was no difference in the expression of respiratory complex proteins in PVAT from control and obese mice (Figure S1), indicating a similar number of mitochondria.

The role of the mitochondrial electron transport chain as a source of increased O2 .‐ generation in PVAT is supported by the observation that the mitochondria‐targeted antioxidant MnTMPyP, a Mn‐SOD mimetic, significantly increased contractions to phenylephrine in PVAT‐intact vessels from obese mice. This is consistent with SOD‐mediated dismutation of increased endogenous O2 ·‐ to generate H2O2, which in turn increases vascular smooth muscle contraction. In fact, the amount of mitochondrial H2O2 was significantly increased in PVAT from obese mice. Furthermore, PEG‐catalase, which catalyses the conversion of mitochondrial H2O2 into H2O, significantly decreased contraction to phenylephrine in aortae, with or without PVAT, from obese animals, further supporting our argument that mitochondrial H2O2 stimulates vascular contraction in obesity. The differential effect of H2O2 on vascular smooth muscle tone has been previously reported in hypertension and is consistent with our results, where H2O2 induces intermittent vascular contraction, an effect abolished by PEG‐catalase (Silva et al., 2013; García‐Redondo et al., 2015).

Obesity also favours increased activity of the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway, promoting cardiac dysfunction, loss of endothelium‐dependent relaxation, increased intracellular Ca2+ and subsequent vascular hypercontractility (Nishimatsu et al., 2005; Naik et al., 2006; Schinzari et al., 2012; Soliman et al., 2015). The RhoA/Rho kinase pathway is a potential contributor to the mechanism by which a higher output of mitochondrial H2O2, derived from PVAT, increased vascular contraction in obese mice. Indeed, the Rho kinase inhibitor Y‐27632 blocked the increased contractions to phenylephrine in PVAT‐intact vessels from obese mice, an effect that was abolished by PVAT removal. The relaxation induced by Y27632 provided additional evidence that PVAT increased RhoA/Rho kinase activity, as aortas from HFD‐fed mice displayed increased sensitivity to Y‐27632‐induced relaxation. The involvement of the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway in vascular dysfunction has also been demonstrated in resistance and conductance arteries of hypertensive animals (Weber and Webb, 2001; Asano and Nomura, 2003). Our data show that the presence of PEG‐catalase reduced Rho kinase activity, strengthening the hypothesis that mROS modulate the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway. ROS generation stimulates Rho translocation and Rho kinase activation, which leads to inhibition of MLC phosphatase, resulting in smooth muscle contraction in endothelium‐denuded rat aorta (Jin et al., 2004). In addition, our data showed that phosphorylation of MYPT‐1, an important Rho kinase target, was increased in PVAT‐intact aortas from obese mice. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating a direct interaction between PVAT and RhoA/Rho kinase signalling in vascular smooth muscle.

The presence of inflammation, imbalanced production of adipokines and oxidative stress in PVAT has been linked to increased vasoconstriction and vascular dysfunction in obesity (Chen et al., 2010; Morgan and Liu, 2010; Szasz et al., 2013; Anusree et al., 2015). PVAT dysfunction in obese pigs has been associated with marked alterations in the proteome profile of the coronary PVAT (Owen et al., 2013). Moreover, reduction in adiponectin production by PVAT and the consequent reduction in the opening of Ca2+ activated K+ channels (BKCa) in smooth muscle has been associated with impaired relaxation of mesenteric arteries in ob/ob mice (Agabiti‐Rosei et al., 2014). Adiponectin negatively modulates cardiovascular inflammation, and reduced adiponectin levels in obesity are associated with increased levels of TNF‐α (Nishimura et al., 2006) and, possibly, with TNF‐α‐induced deleterious effects. In this study, we focused on the role of TNF‐α to promote mitochondrial oxidative stress in the PVAT but have not addressed the possibility that a decrease in adiponectin levels may account for the effects of TNF‐α, which certainly deserves to be investigated.

We have provided evidence that the inflammatory adipokine TNF‐α modulated mitochondrial homeostasis in PVAT. Accordingly, TNF‐α increased H2O2 generation by the mitochondrial electron transport chain in PVAT, and the TNF‐α inhibitor infliximab reduced H2O2 generation in PVAT from obese mice. These observations are in agreement with a recent report showing that epithelial cells stimulated with TNF‐α exhibit reduced oxygen consumption and increased mROS generation (Babu et al., 2015). Of importance, TNF‐α receptor deficient, obese mice did not exhibit PVAT dysfunction, that is, the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT were preserved. In order to offer a better view of the status of the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway, we determined Rho kinase activity in vessels from TNF‐α receptor deficient mice and found a significant decrease in Rho kinase activity in aortas from these mice. This finding provides a link between the Rho kinase pathway, PVAT and inflammation, all contributors to obesity‐associated vascular function.

TNF‐α may alter PVAT mitochondrial respiration by decreasing the uncoupling pathways in the inner mitochondrial membrane, like that promoted by UCP. As protonophores, UCPs promote dissipation of the proton gradient, stimulating electron flux and respiration. Consistent with this hypothesis, TNF‐α significantly decreased UCP‐1 expression in PVAT. Although the mechanism involved in this effect has not been elucidated in this study, TNF‐α‐induced reduction in UCP‐1 has been demonstrated in adipocytes from brown fat (Masaki et al., 1999; Valladares et al., 2001).

There is functional similarity between the PVAT and BAT, and obese individuals exhibit functional loss of both tissues. Recent studies have shown that increased body mass produces ‘whitening’ of BAT, reduces β‐adrenoceptor signalling, favours the presence of unilocular lipids and produces marked mitochondrial dysfunction (Shimizu and Walsh, 2015). The exact mechanisms that lead to BAT damage in obesity are not completely elucidated, but it is known that the whitening effect promotes infiltration of immune cells and increases production of proinflammatory cytokines. These events corroborate data from the present study, reinforcing an association between obesity, inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction.

In summary, this study presents evidence that TNF‐α‐induced oxidative stress is a key mechanism involved in the loss of the anti‐contractile effects of PVAT. Moreover, we describe a previously unknown contribution of mitochondria to increased O2 .‐ generation and its conversion to H2O2 in PVAT. Notably, these changes are associated with increased activation of the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells, leading to vascular dysfunction in obesity.

Author contributions

R.C., N.L., L.A. and R.T. participated in the design of the study; R.C., R.F., C.D. and P.L.‐J. conducted the experiments; R.T., N.L. and L.A. contributed new reagents or analytical tools; R.C., N.L., L.A. and R.T. performed the data analysis; R.C., N.L., L.A. and R.T. wrote or contributed to the writing of the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Table S1 Characteristics of control and obese (HFD) C57BI/6 J mice.

Table S2 Characteristics of control and obese (HFD) TNF‐α receptor deficient mice.

Table S3 Emax (mN) values of phenylephrine‐induced contraction in aorta of control and obese mice.

Table S4 pD2 values of phenylephrine‐induced contraction in aorta of control and obese mice.

Figure S1 Obesity does not modify mitochondrial protein expression in the PVAT. Representative Western blotting images for mitochondrial complexes III (A) and I (B) and VDAC (C) in PVAT from thoracic aorta of control and obese mice. The graphs show the ratio of mitochondrial proteins/β ‐actin expression. Data represent the mean ± SEM; n = 5 for each experimental group.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP‐CRID 2013/08216‐2 to R.C.T. and 2010/17259‐9 to L.C.A.), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil.

da Costa, R. M. , Fais, R. S. , Dechandt, C. R. P. , Louzada‐Junior, P. , Alberici, L. C. , Lobato, N. S. , and Tostes, R. C. (2017) Increased mitochondrial ROS generation mediates the loss of the anti‐contractile effects of perivascular adipose tissue in high‐fat diet obese mice. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174: 3527–3541. doi: 10.1111/bph.13687.

References

- Agabiti‐Rosei C, De Ciuceis C, Rossini C, Porteri E, Rodella LF, Withers SB et al. (2014). Anti‐contractile activity of perivascular fat in obese mice and the effect of long‐term treatment with melatonin. J Hypertens 32: 1264–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, Faccenda E et al. (2015a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Overview. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5729–5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 172: 6024–6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, Faccenda E et al. (2015c). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Transporters. Br J Pharmacol 172: 6110–6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anusree SS, Nisha VM, Priyanka A, Raghu KG (2015). Insulin resistance by TNF‐α is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in 3 T3‐L1 adipocytes and is ameliorated by punicic acid, a PPARγ agonist. Mol Cell Endocrinol 413: 120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardanaz N, Pagano PJ (2006). Hydrogen peroxide as a paracrine vascular mediator: regulation and signaling leading to dysfunction. Exp Biol Med 231: 237–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano M, Nomura Y (2003). Comparison of inhibitory effects of Y‐27632, a Rho kinase inhibitor, in strips of small and large mesenteric arteries from spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive Wistar‐Kyoto rats. Hypertens Res 26: 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu D, Leclercq G, Goossens V, Vanden‐Berghe T, Van‐Hamme E, Vandenabeele P et al. (2015). Mitochondria and NADPH oxidases are the major sources of TNF‐α/cycloheximide‐induced oxidative stress in murine intestinal epithelial MODE‐K cells. Cell Signal 27: 1141–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton KA, Pedley A, Massaro JM, Corsini EM, Murabito JM, Hoffmann U et al. (2012). Prevalence, distribution, and risk factor correlates of high thoracic periaortic fat in the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc 1: e004200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Villacorta L, Li R, Hamblin M, Xu W, Dou C et al. (2012). Loss of perivascular adipose tissue on peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ deletion in smooth muscle cells impairs intravascular thermoregulation and enhances atherosclerosis. Circulation 126: 1067–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XH, Zhao YP, Xue M, Ji CB, Gao CL, Zhu JG et al. (2010). TNF‐alpha induces mitochondrial dysfunction in 3 T3‐L1 adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 328: 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa RM, Filgueira FP, Tostes RC, Carvalho MH, Akamine EH, Lobato NS (2016). H2O2 generated from mitochondrial electron transport chain in thoracic perivascular adipose tissue is crucial for modulation of vascular smooth muscle contraction. Vascul Pharmacol 84: 28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SP, Giembycz MA et al. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa RM, Neves KB, Mestriner FL, Louzada‐Junior P, Bruder‐Nascimento T, Tostes RC (2016). TNF‐α induces vascular insulin resistance via positive modulation of PTEN and decreased Akt/eNOS/NO signaling in high fat diet‐fed mice. Cardiovasc Diabetol 15: 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechandt CR, Couto‐Lima CA, Alberici LC (2016). Triglyceride depletion of brown adipose tissue enables analysis of mitochondrial respiratory function in permeabilized biopsies. Anal Biochem 515: 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández‐Alfonso MS, Gil‐Ortega M, García‐Prieto CF, Aranguez I, Ruiz‐Gayo M, Somoza B (2013). Mechanisms of perivascular adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity. Int J Endocrinol 2013: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbons TP, Kogan S, Aouadi M, Hendricks GM, Straubhaar J, Czech MP (2011). Similarity of mouse perivascular and brown adipose tissues and their resistance to diet‐induced inflammation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: 1425–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YJ, Lu C, Su LY, Sharma AM, Lee RM (2007). Modulation of vascular function by perivascular adipose tissue: the role of endothelium and hydrogen peroxide. Br J Pharmacol 151: 323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Redondo AB, Briones AM, Martínez‐Revelles S, Palao T, Vila L, Alonso MJ et al. (2015). c‐Src, ERK1/2 and Rho kinase mediate hydrogen peroxide‐induced vascular contraction in hypertension: role of TXA2, NAD(P)H oxidase and mitochondria. J Hypertens 33: 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil‐Longo J, González‐Vázquez C (2005). Characterization of four different effects elicited by H2O2 in rat aorta. Vascul Pharmacol 43: 128–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil‐Ortega M, Condezo‐Hoyos L, García‐Prieto CF, Arribas SM, González MC, Aranguez I (2014). Imbalance between pro and anti‐oxidant mechanisms in perivascular adipose tissue aggravates long‐term high‐fat diet‐derived endothelial dysfunction. PLoS One 9: e95312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollasch M, Dubrovska G (2004). Paracrine role for periadventitial adipose tissue in the regulation of arterial tone. Trends Pharmacol Sci 25: 647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga NA, Callera GE, Yogi A, Mecawi AS, Antunes‐Rodrogues J, Queiroz RH et al. (2014). Acute ethanol intake induces mitogen‐activated protein kinase activation, platelet‐derived growth factor receptor phosphorylation, and oxidative stress in resistance arteries. J Physiol Biochem 70: 509–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein AS, Khavandi K, Withers SB, Sonoyama K, Clancy O, Jeziorska M et al. (2009). Local inflammation and hypoxia abolish the protective anti‐contractile properties of perivascular fat in obese patients. Circulation 119: 1661–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzik TJ, Marvar PJ, Czesnikiewicz‐Guzik M, Korbut R (2007). Perivascular adipose tissue as a messenger of the brain‐vessel axis: role in vascular inflammation and dysfunction. J Physiol Pharmacol 58: 591–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Ying Z, Webb RC (2004). Activation of Rho/Rho kinase signaling pathway by reactive oxygen species in rat aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H1495–H1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketonen J, Shi J, Martonen E, Mervaala E (2010). Periadventitial adipose tissue promotes endothelial dysfunction via oxidative stress in diet‐induced obese C57Bl/6 mice. Circ J 74: 1479–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang HL, Hilton G, Mortensen J, Regner K, Johnson CP, Nilakantan V (2009). MnTMPyP, a cell‐permeant SOD mimetic, reduces oxidative stress and apoptosis following renal ischemia–reperfusion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F266–F276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobato NS, Neves KB, Filgueira FP, Fortes ZB, Carvalho MH, Webb RC et al. (2012). The adipokine chemerin augments vascular reactivity to contractile stimuli via activation of the MEK‐ERK1/2 pathway. Life Sci 91: 600–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löhn M, Dubrovska G, Lauterbach B, Luft FC, Gollasch M, Sharma AM (2002). Periadventitial fat releases a vascular relaxing factor. FASEB J 16: 1057–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesi C, Ebrahimian T, Angulo O, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL (2009). Endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and perivascular adipose oxidative stress and inflammation contribute to vascular dysfunction in a rodent model of metabolic syndrome. Hypertension 54: 1384–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez JA (2006). Mitochondrial oxidative stress and inflammation: an slalom to obesity and insulin resistance. J Physiol Biochem 62: 303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki T, Yoshimatsu H, Chiba S, Hidaka S, Tajima D, Kakuma T et al. (1999). Tumor necrosis factor‐alpha regulates in vivo expression of the rat UCP family differentially. Biochim Biophys Acta 1436: 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Lilley E (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): new requirements for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3189–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina‐Gomez G (2012). Mitochondria and endocrine function of adipose tissue. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 26: 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MJ, Liu ZG (2010). Reactive oxygen species in TNFalpha‐induced signaling and cell death. Mol Cells 30: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik JS, Xiang L, Hester RL (2006). Enhanced role for RhoA‐associated kinase in adrenergic‐mediated vasoconstriction in gracilis arteries from obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R154–R161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimatsu H, Suzuki E, Satonaka H, Takeda R, Omata M, Fujita T et al. (2005). Endothelial dysfunction and hypercontractility of vascular myocytes are ameliorated by fluvastatin in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1770–H1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura K, Setoyama T, Tsumagari H, Miyata N, Hatano Y, Xu L et al. (2006). Endogenous prostaglandins E2 and F 2alpha serve as an anti‐apoptotic factor against apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor‐alpha in mouse 3T3‐L1 preadipocytes. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 70: 2145–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omar A, Chatterjee TK, Tang Y, Hui DY, Weintraub NL (2014). Proinflammatory phenotype of perivascular adipocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34: 1631–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oriowo MA (2015). Perivascular adipose tissue, vascular reactivity and hypertension. Med Princ Pract 24 (Suppl. 1): 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen MK, Witzmann FA, McKenney ML, Lai X, Berwick ZC, Moberly SP et al. (2013). Perivascular adipose tissue potentiates contraction of coronary vascular smooth muscle: influence of obesity. Circulation 128: 9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla J, Jenkins NT, Vieira‐Potter VJ, Laughlin MH (2013). Divergent phenotype of rat thoracic and abdominal perivascular adipose tissues. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R543–R552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinzari F, Tesauro M, Rovella V, Di Daniele N, Gentileschi P, Mores N et al. (2012). Rho‐kinase inhibition improves vasodilator responsiveness during hyperinsulinemia in the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 303: E806–E811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu I, Walsh K (2015). The whitening of brown fat and its implications for weight management in obesity. Curr Obes Rep 4: 224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva BR, Pernomian L, Grando MD, Amaral JH, Tanus‐Santos JE, Bendhack LM (2013). Hydrogen peroxide modulates phenylephrine‐induced contractile response in renal hypertensive rat aorta. Eur J Pharmacol 721: 193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skulachev VP (1998). Uncoupling: new approaches to an old problem of bioenergetics. Biochim Biophys Acta 1363: 100–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliman H, Nyamandi V, Garcia‐Patino M, Varela JN, Bankar G, Lin G et al. (2015). Partial deletion of ROCK2 protects mice from high‐fat diet‐induced cardiac insulin resistance and contractile dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H70–H71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SPH et al. (2016). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucl Acids Res 44 (Database Issue): D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradley FT, Ho DH, Pollock JS (2015). Dahl SS rats demonstrate enhanced aortic perivascular adipose tissue‐mediated buffering of vasoconstriction through activation of NOS in the endothelium. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 25: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Hou N, Han F, Guo Y, Hui Z, Du G et al. (2013). Effect of high free fatty acids on the anti‐contractile response of perivascular adipose tissue in rat aorta. J Mol Cell Cardiol 63: 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Swei A, Zweifach BW, Schmid‐Schönbein GW (1995). In vivo evidence for microvascular oxidative stress in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Hypertension 25: 1083–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szasz T, Bomfim GF, Webb RC (2013). The influence of perivascular adipose tissue on vascular homeostasis. Vasc Health Risk Manag 9: 105–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka M, Suzuki H, Shioda S, Sekikawa K, Saito Y, Nagai R et al. (2010). Endovascular injury induces rapid phenotypic changes in perivascular adipose tissue. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30: 1576–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BA, Phillips SJ (1996). Detection of obesity QTLs on mouse chromosomes 1 and 7 by selective DNA pooling. Genomics 34: 389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valladares A, Roncero C, Benito M, Porras A (2001). TNF‐alpha inhibits UCP‐1 expression in brown adipocytes via ERKs. Opposite effect of p38MAPK. FEBS Lett 493: 6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virdis A, Duranti E, Rossi C, Dell'Agnello U, Santini E, Anselmino M et al. (2015). Tumour necrosis factor‐alpha participates on the endothelin‐1/nitric oxide imbalance in small arteries from obese patients: role of perivascular adipose tissue. Eur Heart J 36: 784–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber DS, Webb RC (2001). Enhanced relaxation to the rho‐kinase inhibitor Y‐27632 in mesenteric arteries from mineralocorticoid hypertensive rats. Pharmacology 63: 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Diwu Z, Panchuk‐Voloshina N, Haugland RP (1997). A stable nonfluorescent derivative of resorufin for the fluorometric determination of trace hydrogen peroxide: applications in detecting the activity of phagocyte NADPH oxidase and other oxidases. Anal Biochem 253: 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorzano A, Liesa M, Palacín M (2009). Role of mitochondrial dynamics proteins in the pathophysiology of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41: 1846–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Characteristics of control and obese (HFD) C57BI/6 J mice.

Table S2 Characteristics of control and obese (HFD) TNF‐α receptor deficient mice.

Table S3 Emax (mN) values of phenylephrine‐induced contraction in aorta of control and obese mice.

Table S4 pD2 values of phenylephrine‐induced contraction in aorta of control and obese mice.

Figure S1 Obesity does not modify mitochondrial protein expression in the PVAT. Representative Western blotting images for mitochondrial complexes III (A) and I (B) and VDAC (C) in PVAT from thoracic aorta of control and obese mice. The graphs show the ratio of mitochondrial proteins/β ‐actin expression. Data represent the mean ± SEM; n = 5 for each experimental group.