Abstract

Although the evidence base for treatment of depressive disorders in adolescents has strengthened in recent years, less is known about the treatment of depression in middle to late childhood. A family-based treatment may be optimal in addressing the interpersonal problems and symptoms frequently evident among depressed children during this developmental phase, particularly given data indicating that attributes of the family environment predict recovery versus continuing depression among depressed children. Family-Focused Treatment for Childhood Depression (FFT-CD) is designed as a 15-session family treatment with both the youth and parents targeting two putative mechanisms involved in recovery: (a) enhancing family support, specifically decreasing criticism and increasing supportive interactions; and (b) strengthening specific cognitive-behavioral skills within a family context that have been central to CBT for depression, specifically behavioral activation, communication, and problem solving. This article describes in detail the FFT-CD protocol and illustrates its implementation with three depressed children and their families. Common themes/challenges in treatment included family stressors, comorbidity, parental mental health challenges, and inclusion/integration of siblings into sessions. These three children experienced positive changes from pre- to posttreatment on assessor-rated depressive symptoms, parent- and child-rated depressive symptoms, and parent-rated internalizing and externalizing symptoms. These changes were maintained at follow-up evaluations 4 and 9 months following treatment completion.

Keywords: depression, child, family, family functioning, treatment

Despite substantial advances in the evidence base for treatment of adolescent depression, there are no established treatments for children with depressive disorders (for review, Tompson, Boger, & Asarnow, 2012). Developmental considerations during middle to late childhood, including greater dependence on parents and rapidly changing cognitive capacity, make it unlikely that adult treatments and their adaptations for adolescents can simply be extended downward, pointing to a need for developmentally informed treatment specifically for children. Parents provide support and feedback throughout this period, and children are dependent on their parents’ abilities to interface with the community, support their development, and model and teach coping and other key life skills (Ladd, 1999; Steinberg, 2001). Family-inclusive interventions, therefore, are likely to be particularly beneficial during this childhood period.

Family-Focused Treatment for Childhood Depression (FFT-CD; Tompson et al., 2012; Tompson et al., 2007), a developmentally tailored approach for children ages 7 to 14, includes up to 15 sessions focusing on psychoeducation about depression and skill-building in a family context to enhance coping and increase generalization. FFT-CD addresses the needs of school-aged children and their parents by fostering positive, supportive parent-child interactions to scaffold the development of a positive self, helping parents provide positive feedback on developmentally appropriate achievements, and enhancing family and child coping by focusing on communication, behavioral activation, and problem solving within the family. This article describes FFT-CD, illustrates its implementation with three children and their families, provides case-specific data on outcomes, and discusses common challenges that arise.

Underlying Conceptual and Empirical Roots

The FFT-CD protocol was influenced by interpersonal theories of depression (Joiner & Coyne, 1999), the evidence supporting family treatment approaches for mood disorders in adults and adolescents (O’Connor, Tompson, & Miklowitz, 2015), cognitive behavioral approaches for youth depression (Tompson et al., 2012), an understanding of factors impacting the development and course of child depression (Beardslee, Gladstone, & O’Connor, 2012), and developmental studies of middle childhood/early adolescence (Ladd, 1999; Steinberg, 2001). These influences led to creation of the treatment model and specific adaptations for children.

Interpersonal theories of depression (Joiner & Coyne, 1999) emphasize interpersonal stress and functioning as both risk and maintaining factors. Indeed, recent research underscores the bidirectional association between depression and stress, particularly increased interpersonal conflicts and stressors, and emphasizes how depression leads to “stress-generating” interpersonal interactions which further fuel depression (Hammen, 2006; Liu & Alloy, 2010). This approach views depression as a biopsychosocial phenomenon. Biological and environmental factors contribute to its onset, and negative cognitive processes and interpersonal stress impact course and outcome, leading to a downward spiral of escalating symptoms, negative cognitive processes and stressful events/interactions (Asarnow, Jaycox, & Tompson, 2001). In FFT-CD the therapist focuses on understanding the family’s unique interpersonal processes and, using an integrated family systems and cognitive behavioral model, provides expanded psychoeducation and skills building within the family to increase positive and decrease negative interactional sequences.

FFT-CD’s techniques are based in family psychoeducational approaches, family-focused treatments developed for adults and adolescents, and cognitive-behavioral interventions. Family psychoeducational approaches have been used in the treatment of mood disorders in children (e.g., Asarnow, Scott, & Mintz, 2002; Fristad, Arnold, & Leffler, 2011; Miklowitz & Goldstein, 2010) and adults (for review, O’Connor et al., 2015) and combine education about the disorder with skills development to enhance coping and increase medication compliance. Psychoeducation emphasizes the biological and stress factors that contribute to mood disorders and the need to manage these disorders to improve outcomes. Enhancement of communication and problem-solving are targeted to decrease stress, blame, and burden for both families and patients. Cognitive-behavioral approaches to mood disorders in children have also emphasized coping enhancement through skills development (Weisz, McCarty, & Valeri, 2006), including skills focused on behavioral activation (McCauley, Schloredt, Gudmundsen, Martell, & Dimidjian, 2011). In a departure from psychoeducational approaches, our FFT-CD does not explicitly emphasize medication compliance. The role and efficacy of medication intervention for pre-adolescent-onset depression is more equivocal (Cheung, Emslie, & Mayes, 2005), and parents and children often prefer psychosocial treatment alone for internalizing problems (Bradley, McGrath, Brannen, & Bagnell, 2010; Brown, Deacon, Abramowitz, Dammann, & Whiteside, 2007; Jaycox et al., 2006; Lewin, McGuire, Murphy, & Storch, 2014). In our clinical trial, many parents reported that they contacted us because they wanted a non-medication intervention, and just over 10 % of participants were on an antidepressant. Thus, though a clear discussion of biological factors is included in our FFT-CD, medication compliance is not a key focus. Where youth are taking medications (for any condition), medication compliance may become a focus of family problem solving, but the primary foci are enhancement of family support and reduction of interpersonal stress.

Depression during this developmental period has a number of clinical characteristics and risk factors that make a family approach, such as FFT-CD, particularly appropriate. First, given the familiality of childhood depression, many depressed children are likely to be living with depressed parents, particularly mothers (Tompson, Asarnow, Mintz, & Cantwell, 2015). Further, depressions tend to be temporally linked across family members, with depressions in one family member seeming to be triggered by stress associated with another family member’s depression (Hammen, Burge, & Adrian, 1991), and successful treatment of parental depression is associated with reduction in child depressive symptoms (Cuijpers, Weitz, Karyotaki, Garber, & Andersson, 2015). In the large multisite Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial (Weissman et al., 2006), maternal depression led to reductions in diagnoses of child depression; in a study examining pharmacologic treatment of child depression, improvements in child symptoms were mirrored by improvements in maternal symptoms (Kennard et al., 2008). Interestingly, in neither study were family member symptoms specifically targeted. These findings underscore the potential reciprocal relationship between child and parent depression and further suggest that a family approach, which can address disorders in multiple family members and enhance family functioning, may decrease risk of depressive episodes in the family as a whole. Second, specific family processes and stresses are associated with poor depression outcomes (Tompson, McKowen, & Asarnow, 2009). For example, parental expressed emotion (EE), an index of criticism and emotional overinvolvement in the home, predicts outcome in children with depressive disorders (Asarnow, Goldstein, Tompson, & Guthrie, 1993; McCleary & Sanford, 2002; Silk et al., 2009). The FFT-CD approach was designed to specifically target reduction of EE and enhancement of family support and functioning. Third, depressed children often present with comorbid conditions, particularly anxiety and disruptive behavior disorders (Kessler, Avenevoli, & Merikangas, 2001). Although our FFT-CD may be depression-focused, enhanced family coping, support, and problem solving may have broad effects on child psychopathology.

Integrating Development Considerations

Developmental characteristics during middle childhood through early adolescence influenced the intervention design. Careful attention was paid to constructing a developmentally appropriate/informed intervention that could support durable behavior change and generalization across multiple settings. Three particular developmental considerations were targeted.

First, school-aged children may be uncomfortable talking about problems, instead using avoidance as a coping strategy (Vierhaus, Lohaus, & Ball, 2007). Throughout, we frequently normalized stress and family conflicts. We began with positive examples (i.e., “upward spirals”) before addressing problems (i.e., “downward spirals”). We presented skills slowly to allow the child to learn about the idea and then apply it. Skills were taught and practiced with easy, age-appropriate examples first (e.g., using active listening skills while a family member describes how to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich), then later applied to more emotionally salient examples (e.g., using active listening skills while a family member talks about an argument with another family member). Families are provided handouts and numerous hypothetical examples; once comfortable with the concepts, they generate examples from their own family.

Second, children learn best by being engaged in activities and practice may enhance generalization of skills. In CBT approaches with pre-adolescents, they reported finding behavioral rather than cognitive components most helpful (Asarnow et al., 2002) and we have emphasized those in FFT-CD. Exercises are presented as “games” initially to make them more engaging to school-aged children and increase the likelihood that these “games” could become “family tools” for combating depression. Additionally, the “game” approach often included silly examples that resulted in family members laughing and appearing to have enjoyable in-session family interactions, strengthening “pleasant family activities” —a family-centered behavioral activation strategy. We have found that, likely due to anhedonia and withdrawal, children with depression and their family members may have disengaged somewhat and seem less likely to spend enjoyable time together. These exercises may be useful in decreasing the withdrawal/disengagement and lack of motivation frequently evident in depressed children, providing an opportunity for mutual enjoyment during session, and strengthening family relationships through positive time spent together both in and out of session.

Third, FFT-CD was designed to match the generally more concrete cognitive level of children. Session handouts use simple language, and skills are broken down into small components that can be mastered in a step-wise fashion. For example, giving positive feedback consists of identifying positive behavior (“catching upward spirals”) and giving feedback (“keeping upward spirals going”). In addition, we used poker chips as tokens or “thanks notes” (Rotheram-Borus et al., 2002; Asarnow, Berk, Hughes, & Anderson, 2015) throughout treatment as a strategy to increase expressions of appreciation and positive communication within the family.

Description of the Treatment

Therapist Role

The therapist listens and validates, provides information and teaches skills, models behavior, and engages families in working on new ways of interacting. Although the therapist brings knowledge, parents are regarded as “experts” on their child. The therapist and family members collaboratively adapt the techniques/skills to the needs of the individual family. Family members are encouraged to try activities (i.e., role-playing), and the therapist maintains a hopeful, curious, and collaborative stance. Normalizing and validating parents’ emotions (e.g., frustration, hopelessness) is essential and provides a first step in trying new strategies. Ultimately, as with most treatments, listening and connecting with families’ experiences is essential for competent application of FFT-CD.

Using an interpersonal model of depression, the therapist provides information on the causes and correlates of depression, along with individualized feedback about how these factors relate to the child’s depression. The therapist provides education about the implementation of new strategies for managing symptoms and interpersonal problems. Handouts describe each skill to be learned. Role-playing, behavioral rehearsal, and practice assignments are used to help shape these behaviors. The therapist actively models, directs, and provides verbal reinforcement to family members during this learning process. Again, normalization is frequently used, conveying to family members that though these skills are important, it is natural and understandable for all families to need to practice them. When modeling the skills being learned, the therapist conveys information explicitly (e.g., describing steps in communication training or problem solving) and implicitly (e.g., providing positive attributions about others’ behavior and motives).

Treatment Structure

Following initial parent and child psychoeducational sessions, all session are conducted with the child and parent(s), with the possibility of including siblings and/or, more occasionally, other family members (e.g., grandparents, step-parents) if conflicts with these members frequently contribute to family stress, the relationship(s) may be a particularly effective source of support, or the child and/or parents desire sibling or other family member participation.

Typically, after the initial psychoeducational sessions, remaining sessions maintain a regular structure. The therapist and child briefly meet to check in about recent stressors and complete mood monitoring forms (usually the Depression Self Rating Scale [DSRS]; Asarnow & Carlson, 1985). Family members then join, and participants review positive events (“upward spirals”) of the past week and give one another positive feedback, both verbally (“Saying What You Liked”) and behaviorally (reinforcing with tokens/chips). Homework/practice is reviewed, skill building is introduced, and practice (modeling, role-plays) is used to develop skills. Practice-at-home is an integral part of treatment and is included weekly. We avoided the term “homework,” as many children have negative associations with “homework” and the term “practice” conveys the importance of continuing to improve use of the treatment skills outside of therapy.

FFT-CD includes five modules: (1) psychoeducation, (2) communication skills, (3) behavioral activation; (4) problem solving, and (5) relapse prevention. Although modules typically proceed in order, Modules 2–4 are sometimes reordered to meet the needs of particular families. For example, if families are in a crisis or at an important decision point, problem solving may be used at treatment outset, allowing emergent issues to be addressed.

Individual Modules

Psychoeducation

This module includes three sessions—one with the parent(s), one with the child, and one with the family together—that set the stage for the treatment. The first two sessions are often completed back-to-back during the first week of treatment to increase treatment efficiency. The module’s goals and strategies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

FFT-CD Session Goals and Strategies

| Module Name | Number of Sessions | Goals | Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding Depression (Module 1) | 3 | Join with family |

|

| Present Interpersonal Model |

|

||

| Outline upward and downward spirals |

|

||

| Families Talking Together (Module 2) | 3 – 4 | Increase Positive Feedback |

|

| Promote Active Listening |

|

||

| Improve Negative Feedback skills |

|

||

| Things We Do Affect How We Feel (Module 3) | 2 – 3 | Identify pleasurable events/activities |

|

| Promote Assertiveness |

|

||

| Plan enjoyable family and individual activities |

|

||

| We Can Solve Problems Together (Module 4) | 3 – 4 | Part 1: What’s the Problem? | |

| Enhance Problem-Identification |

|

||

| Institute Mood Monitoring |

|

||

| Part II: Solving the Problem | |||

| Teach the family a Problem-solving Model |

|

||

| Solve Family Problems |

|

||

| Saying Goodbye (Module 5) | 1 – 2 | Promote skill generalization |

|

| Empower family to continue process |

|

||

| Plan for future |

|

||

Through listening to many families, we have affirmed some central assumptions that guide psychoeducation. First, all families are different. Children become depressed for many reasons and through a variety of pathways, and depression impacts families in myriad ways. Many depressed children experience peer and family stress, parental psychopathology, learning and behavior problems, and other stressors. Second, parents and children have often tried many strategies before entering this treatment. Acknowledging that some of these efforts have been partially successful recognizes and validates family efforts at coping. Collaboration, a core principle of CBT approaches, is essential here. The therapist often conveys the idea that “we have some ideas and strategies that work with lots of families; let’s try some things out and figure out what works best for your family.” Third, parenting in general is often stressful and parenting a child with depression can be especially so. Frustration, self-blame, defensiveness, and worry are frequent, and understandable, in parents of children with depression. Symptoms of anhedonia, irritability and social withdrawal are difficult for parents to manage and cope with, and children often have challenging comorbid disorders.

Within this framework, parent session goals include: providing psychoeducation about depression tailored to their child’s presentation/experience (including symptoms, contributing factors, course, potential treatments), supporting and highlighting the importance of parents’ roles as models and change-agents for their children, emphasizing “stress” in perpetuating family difficulties and child problems/symptoms, and refocusing the problem from “fixing” the child to helping the family to cope with stress. Therapy is presented as an opportunity to learn skills for overcoming depression and for the parents to develop strategies for promoting the child’s recovery. Rather than focusing on potential parent deficits, this approach emphasizes the essential role of parents, their strengths, and their power to help their child. Parental psychopathology may be discussed during these psychoeducation sessions, as parental depression is common among youth with depressive disorders (Tompson et al., 2015). Discussion of parental depression can be used to enhance parents’ empathy for their child’s challenges, and parents are frequently encouraged to pursue or continue their own treatment should depression interfere with parental functioning and/or with their ability to engage in the ongoing treatment.

Module 1 then proceeds to an individual session with the child, in which the therapist engages the child in a discussion of “happy,” “sad,” and “angry” feelings, allowing the therapist to assess the child’s ability to describe his/her emotional experience. The therapist presents an interpersonal CBT model linking thoughts, actions, and feelings, emphasizing how this relates to family and interpersonal situations, and how one’s own behavior, the behavior of others, and moods are all connected. Although the CBT model guides our thinking in this treatment, the focus on the interpersonal model is central, and we tell the child that “in this treatment we’re going to be talking a lot about these two pieces—the actions and the feelings.” We then present an interpersonal model linking mood with both one’s own behavior and the behavior of others. The central point of the interpersonal model is made—moods influence our interactions and our interactions influence our moods. By reducing conflict and stress in relationships and getting more support in dealing with stress, the child can begin to feel better.

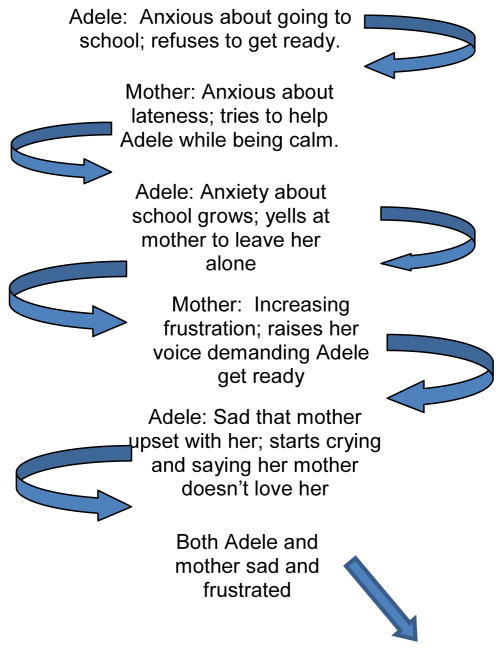

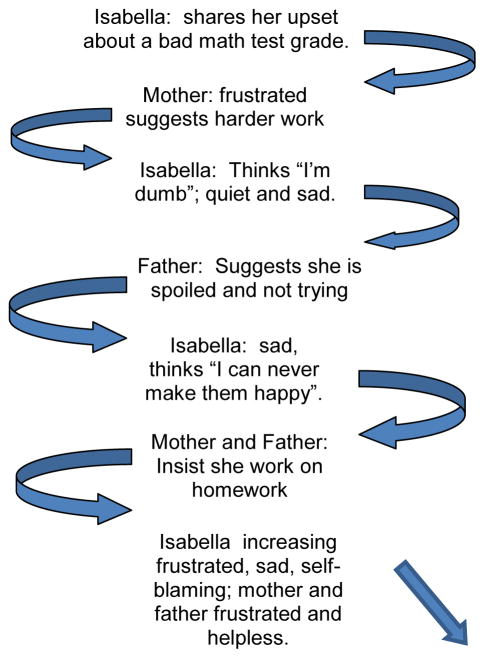

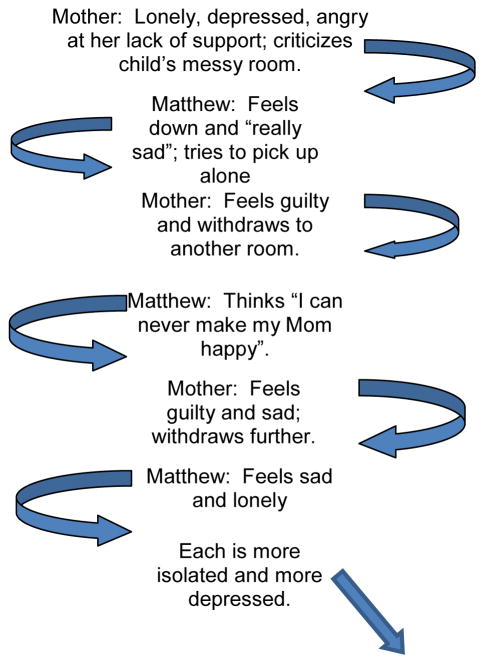

In the final Module 1 session, the therapist reviews the interpersonal depression model and the rationale for FFT-CD with the parents and child together. The therapist establishes the family as the unit of treatment by reframing the problem as an interpersonal one whereby working together parents and children can help combat depression and create ways of responding within the family that reduce stress and enhance support and enjoyment for all members. In this session, the handouts about the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and about the relationship between mood, one’s own behavior, and others’ behaviors, are reviewed, often with the child “teaching” the parents about the concepts from the child-only session. Children and their families are provided information about the ways in which family and other social interactions affect mood, using the concept of emotional spirals (illustrated on handouts). The idea of upward and downward interactional spirals is presented and the family is encouraged to provide examples. Throughout, negative interactions are normalized and their role in perpetuating depression is emphasized. Normalizing is used to remind families that all families experience negative, as well as positive, spirals, to reduce family members’ blaming of others. We often “disclose” examples of other imaginary or real families to emphasize the ordinary nature of these processes, how they can become a problem, and how they can be understood and changed. In “upward spirals” (Figure 1) positive interpersonal interactions contribute to positive emotions, which further fuel positive interpersonal interactions. In “downward spirals” (Figures 2–4), negative interpersonal communication contributes to negative emotions, which further contribute to negative communication, and so on. Family members are encouraged to identify similar patterns within their families. Thus, the session focuses on identifying the understandable patterns that families get into when someone is depressed or confronting high levels of stress and to engender hope that family members can thus have some positive, helpful impact on the depressed individual. The rationale of the treatment is clearly laid out —”building skills to stop downward spirals and to start upward spirals and keep them going.”

Figure 1.

Example of an Upward Spiral

Figure 2.

Adele’s Downward Spiral

Figure 4.

Isabella’s Downward Spiral

Communication Training

Communication training or “Families Talking Together” is typically 3 to 4 sessions. Goals and specific techniques are listed in Table 1. Overall, we aim to improve family communication, increase the child’s assertiveness skills, decrease depressive withdrawal and irritability, engage the family members, and encourage empathy. Specific skills include giving positive feedback to other family members (e.g., saying what you liked, being specific, saying how it made you feel), active listening (e.g., paying attention, asking questions, confirming what was said), and giving corrective feedback (e.g., saying exactly what it was you didn’t like, how it made you feel, and what you would rather the person do next time). A game is introduced in which participants draw cards with positive or negative statements written on them and give others the (sometimes silly) feedback. Handouts, role-plays, behavioral rehearsal, and practice at home are used to help shape these behaviors. The therapist actively models, directs, and provides verbal reinforcement to family members during this learning process. Again, normalization is frequently used, conveying to family members that though these skills are important, it is natural and understandable for all families to need to practice them.

To facilitate the transition from the “Understanding Depression” module to communication training and relationship enhancement, tokens of appreciation (brightly colored poker chips) are introduced. In session, the therapist models using the tokens to express appreciation and give positive feedback and the child and parents practice expressing appreciation in a series of games designed to promote positive feedback. For example, after a parent or child describes a positive family interaction during the week, the therapist might give them a token to express appreciation for practicing positive interaction and sharing this practice in session. Between session practice includes “giving away” tokens to promote generalization of positive family communication patterns to the home environment. Family members are each given a number of tokens (often five) with the instructions that they must give them all away by noticing the nice things others are doing. Children often respond with surprise and questions about “what do I do if I get some from other people?”; we instruct them to keep giving those away to others as well, making it a game for family members to play. It is important to emphasize that, unlike traditional token economy approaches, the goal is not to earn more tokens or to exchange them for awards. Rather, the token practices are intended to focus family members on the positive, provide a fun game-like exercise that enhances communication and provides information about appreciated behaviors, and encourage social reinforcement. In our work, we have found that families frequently enjoy using these tokens both in session and during the week, and a number have reported with humor how, in the jumble of busy family life, they found some of the tokens again weeks later “under the seat of the car” and put them into play while on the go! However, they are not effective with all families, and their use may be tailored for individual and children (e.g., tokens versus notes, formal or scheduled use versus spontaneous or unscheduled).

For older children, we often used “thanks notes,” an approach from the SAFETY intervention for suicidal youths (Asarnow, Berk, Hughes, & Anderson, 2015), that uses small Post-it notes or items on which family members and/or the therapist write a “thank you” for an appreciated behavior or characteristic. This approach has the advantage of giving children and family members a concrete reminder of behaviors and characteristics that are appreciated and allows for family members to use “thanks notes” as positive messages when they are not physically present (placing one in a lunch box or leaving one on the pillow when parents are out for the evening).

We have found that using multiple games to introduce and practice skills enhances learning and helps in keeping sessions enjoyable and positive. We start with neutral topics, move to more emotion-laden ones, and finally to emotional, personally and temporally relevant topics. For example, we used these steps during Active Listening training. Components of Active Listening include eye contact, careful attention to what the other person is saying, communication that one is indeed listening (nodding, saying “uh huh,” asking questions), and summing up to make sure one has heard accurately. There is also an emphasis on not responding until you’ve clearly heard and reflected what was said and being succinct (particularly given the brief attention spans of younger children). We provide a handout that outlines these components, model an example of active listening and summarizing, and then proceed to practice role-plays using written prompts that family members randomly draw from a box/hat. First we practice with nonaffective content, emphasizing that in listening actively we must attend carefully to content. A family member draws a prompt asking him/her to describe a very concrete activity in some detail (e.g., packing a lunch, walking to school, setting up a board game) as the other family member listens actively. Others in the room, including the therapist and family members, then critique the listener, with an emphasis on praising what they are doing right and gently pointing out areas of potential improvement. Second, practice shifts to affective content but prompts focus on others’, rather than one’s own, emotions (e.g., describe a girl’s thought and feeling after getting a bad grade on a test, describe a boy’s thoughts and feelings when waking to dark and rainy morning when he’s planned a day at the beach). Third, and finally, practice involves real and personal examples to help family members to use the skill to actively attend to others’ feelings and to promote affective disclosure (e.g., describe a time when you didn’t get something you really wanted). At each step, family members take turns in the speaker, listener, and observer roles.

Just as our practice-in-session is gradual, so too is the practice-at-home. For example, after the first positive communication session we assign a “catching upward spirals” practice designed to help family members notice positive interactions and their association with positive mood. The next week we expand on this practice with a “keeping upward spirals” going practice, which extends the monitoring of positive interactions with the addition of communicating that positivity to other family members. These exercises are reviewed at the beginning of each session. Some family members have difficulty completing practice at home and will come to sessions with incomplete work. In those situations, we then do the work in session. Should this continue to be a problem, we engage in problem-solving exercises around completing this practice at home.

Behavioral Activation

“Things We Do Affect How We Feel” takes 2 to 3 sessions and is focused on behavioral activation principles, emphasizing both general wellness and managing mood. The goals of these sessions (see Table 1) are to increase the number of enjoyable activities in the child’s life (a common component of CBT for depression; e.g., McCauley et al., 2011) and to increase positive family interactions. Within the FFT-CD model behavioral activation is framed as a strategy for “starting upward spirals,” thus tying it closely to the interpersonal model of depression core concept of treatment and maintaining a consistent treatment model for families that spans across the different FFT-CD skill modules. Each member specifies several activities that can be used to increase daily enjoyment (a wellness strategy; e.g., talking a brief walk each day) or make him or her “feel better after a rough day” (mood management strategy; e.g., taking an impromptu walk with the dog). The therapist uses this discussion to normalize stress, to emphasize measures focused on reducing its impact, and to encourage communication of needs between family members. Sharing individual lists in session helps generate greater empathy. Generating activities that can be engaged in independently, with friends, and with family is emphasized as it creates greater flexibility in coping across many situations, balances working toward greater family bonding with the need to encourage growing child autonomy and social activities with friends, and recognizes that others aren’t always available or interested in participating in a given activity. Because children can sometimes be unrealistic in generating options for daily use (e.g., Disney Land, skiing), we make a point of including a few of these as potential future family activities and also try to generate more accessible daily activities (e.g., board games, athletic activities, reading together).

Family members use communication exercises to ask other family members to engage in activities using “asking for what you want” skills. Families are then encouraged to plan and implement several fun activities together. Care is taken to help them select “do-able” activities that require limited resources and time, increasing the diversity of activities (e.g., solo, family, and friend activities), and linking improved mood to engagement in activities. Activity planning requires specifics—dates, times, resources—and this provides an early opportunity to note family strengths and/or difficulties that might arise in more general problem-solving.

Problem Solving

In “We Can Solve Problems Together” (3 to 4 sessions) skills are broken down to enhance learning of problem identification and problem solving. Goals and strategies are outlined in Table 1. The goals of the first section of this module are to have family members develop problem identification skills, to practice self-monitoring of emotional states, and to reframe problems as choices and opportunities to problem-solve. We have noticed that pre-adolescent children are often reticent to admit problems and normalization is essential—“all kids have problems . . . a problem is a choice . . . when you decide what to wear to school, you have a problem.” Effective problem solving cannot take place when emotions are too high. We work on monitoring mood states through taking our “emotional temperature.” We have each family member list problems they have had recently and how “hot” they were at the time. The emphasis is placed on solving problems in a preventive way when temperatures are cool to moderate. Discussions focus on emotion-regulation strategies for when temperatures are too high and on picking solvable problems (e.g., you can’t change the past).

The goals of the second section of this module are to practice conflict-resolution skills and to empower the family to solve and become more flexible in approaching problems. We have found that enhanced communication alone can help with many family problems, and problem-solving approaches serve as a next step when communication of like/dislike is not sufficient. Standard problem-solving models are taught, including (a) agreeing on the problem, (b) brainstorming possible solutions, (c) evaluating options, (d) choosing the optimal solution(s) and planning their implementation, (e) carrying out the solutions, and (f) reviewing the success of the implemented solution(s). Several helpful caveats have emerged in our problem solving and bear mentioning. First, most problems involve more than one person, and solutions are more likely to be successful if they involve some changes on the part of all involved family members. One-person solutions reinforce the “identified patient” concept, tending to blame that individual for ongoing difficulties. Second, stay focused on the present situation and stop any attempts to dredge up old examples of similar problems. The focus should be on what is to be done in the “here and now.” Avoid getting side-tracked. Third, work on one problem at a time. One specific problem is more likely to be solved and less likely to go “off track.” It helps to pick less complex problems at the outset, as it allows family members to work on the skill and enhances the likelihood of success. Fourth, using the communication skills may help focus and define the problem in a more behavioral way. Fifth, even when a problem-solving solution is reached, work out the details. Little problems can keep solutions from being implemented. Finally, we often predict that the initial solution will not be successful and will need to be revised—“If this was easy to solve, it would be solved already!” We often suggest that the initial solution is an experiment to see what might work better.

Termination

This module—“Saying Goodbye” —takes 1 to 2 sessions. Goals, outlined in Table 1, include engaging in additional practice in problem solving, enhancing generalization of skills, addressing relapse prevention (e.g., identification of symptoms to look out for and a plan for how child can talk to parents), and establishing a regular family meeting time. During these sessions, the family members are praised for their hard work, progress is acknowledged, and further work planned as necessary. The child is presented a colorful folder including all the handouts from the treatment; these are briefly reviewed both to illustrate the gains made by the family and to remind members of the strategies available for coping with future stressors. Family members are encouraged to predict upcoming stressors (i.e., new school year, transitions) and use problem-solving strategies to do anticipatory planning. A problem-solving exercise is conducted to solve the problem “how can you keep your new skills going” after termination. One common solution is to continue to meet weekly as a family to communicate and problem solve, in place of the standard therapy meeting time. Liberal use of tokens was used to help keep this session focused on positive achievements and family gains. Following treatment, the therapist should remain available for booster sessions to facilitate maintenance of treatment gains and crisis management.

Special Issues in Treating Depression

As with evidence-based treatments in general, tracking treatment progress is essential. This can be accomplished using a range of symptom checklists for both depression and additional comorbid concerns; in our treatment, we used the Depression Symptom Rating Scale (DSRS; Asarnow & Carlson, 1985). In addition, we tracked suicidal thoughts and behaviors and nonsuicidal self-injury. Though deaths by suicide do occur in children under age 14 (for review, see Soole, Kolves, & De Leo, 2015) and suicide is the third leading cause of death in children, ages 10 to 14 (CDC, 2013), high levels of suicidal ideation in depressed younger children are less common than in adolescents or adults. Reported rates of suicidal ideation in younger children vary —1.9% in 7- to 12-year-olds (Gould et al., 1998) to 5% in 9- to 11-year-olds (Kerr et al., 2008) to 10% in 8-year-olds (Thompson et al., 2005). Given the limited understanding of suicidality in young children (Tishler, Reiss, & Rhodes, 2007), it is important for those working with depressed children to carefully assess for thoughts of death, self-injurious behaviors (considering level of lethality from the child’s perspective), and parent-report of death- or suicide-related talk. We supplemented the questions on the DSRS to include two items on suicidal ideation. Where items indicating possible suicidal ideation were endorsed, the therapist questioned the child for further information. Questions were asked in a developmentally appropriate manner, with thoughts described as “something you say to yourself” or “something you hear in your head” to those children too young to understand cognitions, and intent described as “hurt yourself on purpose.” If a child endorsed suicidal thoughts, behaviors, or nonsuicidal self-injury, parents were made aware and a safety plan was developed. The safety plan included strategies for distracting or self-soothing, as well as identified supports. Additionally, the therapist would discuss the importance of increased monitoring and addressing home safety (by removing access to lethal means).

Method

Participants

Three children and their family members who were participants in a study comparing a family-based treatment to an individually based treatment for child depression served as subjects for this set of case illustrations. Cases were selected to illustrate common characteristics and challenges in treating children suffering from depression and their families and provide an opportunity to demonstrate the flexible application of core treatment components. First, the children chosen include both a boy and girls and reflect a range of ages to which this treatment is optimal. Second, children with depression differ in terms of severity/chronicity and comorbidity; we have included children with major depressive disorder (MDD) and “double depression” (MDD/DD – MDD and dysthymic disorder), anxiety disorders and learning problems. Finally, children with depression frequently present with numerous family and psychosocial stressors. Thus, we have included cases in which children and their families are grappling with parental psychopathology, academic and peer stress, and family conflict. The three cases described below were referred from school guidance, radio advertising, and print/Internet advertising. They did not request family treatment but were randomly assigned to FFT-CD. Cases have been disguised to protect the identities of participants, with names and details changed to protect anonymity. The research was approved by Institutional Review Boards at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and Boston University (BU) and all children and their parents provided informed assent/consent.

Participants were evaluated at baseline, posttreatment, and at 4- and 9-month follow-ups by independent evaluators who were naive to treatment condition.

Therapists

The therapists were two licensed psychologists who were part of the study team at their respective sites (DAL at BU; JLH at UCLA). Each therapist underwent a 2-day training in FFT-CD implementation with the first author; this training included didactics, case illustration, and role-plays. Each therapist then had two intensive training cases, including audiotape review and supervision for each treatment session. After implementing the treatment with fidelity on both training cases, therapists were considered certified FFT-CD providers. Ongoing supervision was provided weekly with periodic audiotape review. To evaluate treatment fidelity, independent raters used a 7-point rating scale to evaluate FFT sessions on adherence to the general treatment model and competence in providing the treatment. For each of the three cases, three sessions were randomly selected (one each from Sessions 1–5, 6–10, and 11–15) and rated. In all cases scores were high for adherence (average scores across 3 sessions for Case 1 = 7; Case 2 = 7; Case 3 = 6.67) and for competence (average scores across 3 sessions for Case 1 = 7; Case 2 = 7; Case 3 = 6.67).

Measures

In evaluating clinical status, both diagnostic and continuous symptom measures were included, and we chose the most psychometrically sound interviewer-, self-, and parent-report measures. DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) diagnoses were based on interviewer ratings from the K-SADS-PL (Kaufman et al., 1997) administered to the parent about the child and to the child about him/herself. Interviewers were doctoral- or master-level clinicians who received structured training in administering and scoring the KSADS. In the larger study estimates of inter-rater agreement based on 60 cases independently rated by two diagnosticians indicated excellent reliability for any depressive diagnosis (kappa = .91). Interviewer-rated depression severity over the past 2 weeks was measured using the clinician-rated CDRS-R (Poznanski & Mokros, 1996), with Total CDRS ≤28 considered remission in antidepressant trials with youth (Bridge et al., 2007), and interviewer-rated global functioning was assessed using the Children’s Global Adjustment Scale (C-GAS; Shaffer et al., 1983). Inter-rater reliability was high for total CDRS-R (ICC = .94, p < .01) and C-GAS (ICC = .77) in the larger trial. Children self-reported depressive symptoms on the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1996). Parent-report questionnaires included the CDI and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991).

Case Examples

FFT-CD CASE 1 VIGNETTE: “Working with Depression and Anxiety”

Initial Presentation

Adele, a 9-year-old Italian-American girl, was in the 3rd grade and lived with her parents and 4-year-old brother. She was diagnosed with double depression. According to Adele’s parents, she had been “sensitive” and difficult to soothe as an infant, had experienced clinically impairing separation anxiety as young child, and, upon starting elementary school, demonstrated great anxiety about what to wear to school, resulting in frequent refusal to dress in the morning. Adele’s parents recalled some symptoms starting during Kindergarten: low mood and irritability, difficulty sleeping (long latency to sleep and frequent night-time waking), low self-esteem and difficulty concentrating. They reported that during the last month, these symptoms worsened and new ones emerged, including lack of enjoyment of once fun activities, increased fatigue, decreased appetite, excessive guilt, and saying she wished she was “dead.” Similarly, Adele reported feeling sad more days than not, especially at school, and thinking about things she’d like to change about herself. She reported feeling guilty when another child was reprimanded, even though she had done nothing wrong. Though she thought things might get better, she was not able to articulate anything she was looking forward to. Mother’s target problems included: concerns about Adele’s safety; low self-esteem, particularly during homework time; her unhappiness; and difficulties getting ready for school and the associated anxiety. Although anxiety is not necessarily a focus of FFT-CD, it often contributes to downward spirals and integration of anxiety-focused interventions may become a part of problem-solving associated with reducing these downward spirals.

Early Phase of Treatment

Adele and her parents were highly motivated. Initial sessions focused on engaging the family and explaining the treatment rationale and plan. Although typically sessions focus on the depressed youth and her parents, due to a lack of child care, the family was faced with the choice of having one of the parents stay home (or in the waiting room) with the brother or have him in the treatment room. In discussion with the therapist, the family decided to have him in the room, playing independently for some sessions and joining in when possible (e.g., handing out and receiving tokens). This allowed Adele to see how even with him present, her parents were able to focus primarily on her and work as a subsystem. Adele and her parents easily provided examples of downward and upward spirals during the psychoeducation module. Typically, a downward spiral would occur when getting ready in the morning (Figure 2) or doing homework in the afternoon. The therapist highlighted how, not by the fault of anyone, each would respond to the other’s stress by getting more stressed. Adele’s parents noted that when they tried to support Adele, for example, with her difficulty putting on clothes in the morning, she would often become angrier with them. The therapist used this opportunity to normalize both downward and upward spirals, and note that the goal of treatment was to learn more effective ways to decrease (and stop) downward spirals and start (and maintain) upward spirals. In the session with Adele’s parents alone, Adele’s mother reported understanding Adele’s symptoms because she had also suffered from depression. Although this increased her empathy, she also felt guilt, worrying that her own struggles with depression may have set up Adele for similar struggles.

Middle Phase of Treatment

This phase focused on communication and problem-solving skills, starting with increasing positivity by “saying what you liked.” Adele’s family picked up this skill easily and enjoyed giving tokens to one another for both real and made-up silly reasons. By the 4th session the family began working on active listening. As is common for many children and parents, giving cues that indicate active listening (e.g., nodding, saying “uh-huh”) came more easily to Adele and her parents, though it took more practice for them to check out what they heard by repeating it back. Their default response was either to respond to the statement by providing their own opinions (instead of checking out what they heard first), or repeating back one aspect of what they heard while missing key points. Normalizing this challenge, the therapist used it as an example for the family of the importance of checking out what is heard, as, even when people think they’ve listened carefully, it’s easy to miss things (and, for parents, it’s best to keep statements short if they want their child’s full attention). After covering the “saying what you didn’t like skill,” the family used their communication skills to discuss the downward spiral that occurred around getting dressed for school. For the bulk of the session, Adele and her parents alternated speaking and listening roles. A parent would say what was disliked in the morning and what was preferred, and Adele would actively listen and check out what she heard. Upon confirmation that she heard the parent’s statement accurately (sometimes with a few attempts), she would share her opinion and parents would actively listen. Through this iterative process, each expressed their needs and preferences, and they agreed on a plan to attempt, which, with only minor tweaking in following weeks, was successful.

Building off of the success of communication skills for solving a problem, the therapist and family moved on to the problem-solving modules to learn how to solve problems collaboratively when good communication alone wasn’t sufficient. After practicing with made-up and less emotionally heated problems, the family tackled the problem of stress doing homework. Perhaps the most useful part of problem solving for the homework problem was defining the problem accurately. Through active discussion, it became clear that “homework stress” really represented a set of problems: Adele’s worries about making a mistake, Adele wanting to spend less time on homework and more time with her mother, Adele not wanting to miss out on family activities, and Adele finding her brother’s behavior distracting. Each problem was then addressed individually. Through the problem-solving module, the therapist was able to incorporate other behavioral techniques, such as having “practicing making mistakes” be one of the solutions to Adele’s worries about making a mistake to encourage opportunities for exposure.. Three of the problems were discussed in two separate sessions and the fourth problem was assigned to complete together at home, and then reviewed in session.

Final Phase of Treatment

This treatment phase focused on solidifying existing skills and relapse prevention. Doing fun activities together was a preexisting strength of the family, so the focus on this skill was brief, but it was included to reinforce the importance of maintaining these activities. Communication and problem-solving skills were furthered by continued practice. Each week the parents and Adele would report on the week’s upward spirals and skills used, and raise any downward spirals to focus on in session. The therapist gradually transferred leadership of the discussion to Adele and her parents, so that they discussed the problem, identified the skill(s) to use, and used those skills with decreasing therapist input. By the final session, Adele and her parents agreed that they were ready to use these skills independently, and that downward spirals were significantly less frequent and severe compared to when they started treatment.

FFT-CD CASE 2 VIGNETTE: “Building Resilience Into the System”

Initial Presentation

Matthew was an 8-year-old European-American boy in the 2nd grade living with his parents and 18-month old sister. He and his mother reported that his depressive symptoms began about 1 year previously. He began therapy at that point, but the therapy was disrupted when the family relocated 6 months ago due to his father’s job. They moved from a small suburb with a strong family support system to a large city with little support. Matthew reported being “mostly excited” about the move, as he liked the adventure of it, but “really sad” to be away from his friends and family. Although he had close friends at his former school, he had difficulty making friends at his new school. His depressive symptoms worsened around the time of the move. Matthew’s mother described him as “very, very smart” and “articulate,” with restricted interests, including dinosaurs and airplanes. She noted that although he could be interested in and engage with others in conversations about other topics, he preferred to focus on his main interests. Although early evaluation had ruled out an autism spectrum disorder, Matthew had a number of social challenges. Despite frequent dysphoria, Matthew was not anhedonic, as he reported being happy at home, feeling close to both parents, and enjoying family activities, such as camping, going to the library, and doing science experiments. Matthew’s mother reported that the foursome spent a lot time together, particularly since moving, as they did not know many local families. She reported her own history of severe depression; having been treated successfully with medication and therapy, she reported being symptom free for the past year.

Early Phase of Treatment

Matthew and his mother attended 15 sessions of FFT-CD, and his father joined in when his work and travel schedule allowed, approximately one third of sessions. In the first few weeks, they focused on communication skills. They enjoyed the “Saying What You Like” skill, using the token system both in and out of session to reinforce helpful statements and behaviors. Matthew excitedly reported in Session 3, “We traded dots at home!” The presence of his younger sibling in sessions was challenging at times, as it divided his mother’s attention. However, the therapist included her when possible (e.g., giving her tokens to use/drool on), and the mother made sure to have toys and snacks available to distract her. Matthew did not seem to mind having the sister in the room and even included her in certain silly examples and exercises.

Matthew expressed some frustration that his father, who worked full-time, was not in the sessions. Matthew and his mother collaborated with the therapist to identify ways in which the father might be involved in treatment, including asking him to attend sessions, teaching the materials to him at dinner after sessions, and including him in weekly practice assignments. Matthew expressed interest in all of these ideas and, with obvious delight, was successful in bringing his father to session following this discussion. The father’s participation in the skills review and role-plays made it clear that the family had been practicing skills at home. Matthew’s father excelled at reinforcing that Matthew had taught him skills, stating, “I learned about that from him” and praising his skills use in session. The family was readily able to apply the concepts to their family interactions. Matthew particularly enjoyed the silly examples in the role-plays (e.g., “I liked it when you went bowling in your pajamas”), giggling with his parents.

In a brief individual meeting, the father noted his concerns with Matthew’s ability to regulate emotions, as he was easily angry and struggled to recover. The therapist provided additional psychoeducation about the role of irritability in childhood depression and how FFT-CD skills could help Matthew learn ways to manage his emotions through interactions with others. Although the emotion thermometer is often not introduced until problem-solving, it was implemented to aid Matthew in monitoring the intensity of emotions.

Middle Phase of Treatment

The next phase of treatment focused on identifying downward spirals and addressing them with communication or problem solving. Matthew’s father frequently joined, and the family was active and engaged during treatment sessions. Parental marital tension became apparent, but the therapist was able to keep the family focused on role-plays and Matthew’s perspectives to keep the tension from fully playing out in session. Sample downward spirals included conflict related to chores and computer time, as well as spirals related to parents’ mood states and stress levels. For example, the mother was able to identify that when she has had a day where she felt more down, stressed, or not supported, she was more likely to be “short” with Matthew, which then would lead him into a downward spiral (see Figure 3). The family used the Fun Activities module to focus on building more positive experiences in the family such that everyone’s stress was reduced, helping to prevent some of these spirals. Additionally, the therapist met separately with the mother to check-in and gave referrals for her to see a therapist due to her increased depressive symptoms. Other downward spirals related to Matthew’s difficulty in developing and maintaining friendships. The family and therapist used the Fun Activities module to brainstorm activities Matthew could do with friends, such as his mother setting up play dates and his joining classes at the local community center, as well as setting up some summer day camps.

Figure 3.

Matthew’s Downward Spiral

The therapist introduced the problem-solving module by highlighting the many problems Matthew had successfully solved after moving to the city, highlighting his strength in this area. The family decided to address the problem of eating dinner together, as the father had been working later and others were hungry earlier. The family brainstormed possibilities, with the therapist highlighting but not judging any possibilities and throwing in silly ideas as well (e.g., Matthew and his mother go to work and eat on the father’s desk). This exercise occasionally tripped on additional marital conflict, but the therapist was able to keep the focus on the defined problem by meeting briefly with parents to explicitly acknowledge the conflict, redirect the focus of the treatment to the child, and refer the parents for couples’ treatment.

Final Phase of Treatment

Matthew demonstrated great gains during FFT-CD and clearly benefitted from learning the skills, as evidenced by his reporting using the strategies at home. During treatment, it became increasingly apparent that his parents were struggling in their relationship. Fortunately, FFT-CD had helped to build resilience into the system such that his parents were able to use the skills to support Matthew’s continued improvement, even while making some difficult decisions about their family situation. In Session 11, his mother reported that she and his father had decided to separate. Following treatment completion, one booster session was conducted at the time of the follow-up assessment. Matthew had continued to maintain gains made during the treatment.

FFT-CD CASE 3 VIGNETTE: “A Culturally Sensitive FFT-CD Approach”

Initial Presentation

Isabel, a 10-year-old Mexican-American girl, was beginning 5th grade and living at home with both parents and a 6-year-old brother. She had suffered with low levels of depressive symptoms since the middle of her 3rd grade year and had been irritable at school, which her mother originally attributed to Isabel not working hard enough and having troubles with teachers. Toward the end of 4th grade, Isabel’s depressive symptoms worsened, leading to a diagnosis of double depression. Isabel reported that she would often get in trouble at school for talking in class or asking repeated questions and at home for annoying her brother. She also reported frequent worries that her parents might divorce and felt guilty and that she was causing stress and fighting between her parents. Isabel also reported that she “doesn’t always understand” her schoolwork and that her grades have been declining since 3rd grade. Isabel’s mother expressed frustration that Isabel “does not seem to like school” and reported trying various strategies to motivate Isabel to do homework at night, but that “nothing has really worked.” Isabel and her mother described a close family who enjoyed spending time together, particularly with extended family. Isabel reported feeling closest to her mother.

Her parents had immigrated to the U.S. as teenagers and, although quite conversant in English, the family spoke primarily Spanish at home and held many traditional Latino cultural views. The father played the dominant role in the family and was viewed as having primary responsibility for providing for and protecting family members (a concept often referred to as machismo). It was important for the therapist to understand and respect the father’s role, and gain his consent and leadership in the treatment sessions, while also recognizing that depression in girls is not always viewed as something needing treatment. Indeed, the concept of marianismo refers to the belief that suffering for women may be revered and related to spirituality. Further, while there is no clear translation for the concept of simpatia, individuals from Latino culture may be used to “warmer” interpersonal relationships and interactions. As such, it was important for the therapist to express care and concern for the well-being of the entire family and to engage in pleasant, warm interactions with the family (e.g., avoiding direct confrontation).

Early Treatment

Isabel and her family attended 15 sessions of FFT-CD. Sessions typically included Isabel, her mother, and her father, with her brother joining occasionally. In the initial session, the therapist provided psychoeducation about depression to Isabel’s parents. The father reported that growing up in rural Mexico, his family did not speak about mental illness or use mental health services. The therapist worked to understand his views and beliefs about what could be helpful for his daughter and family, engaging him and his wife in treatment process, and to develop a view of treatment that the parents felt good about and could support. With time, both parents and Isabel actively pursued treatment goals and Isabel was able to use the interpersonal model to describe situations at school to her parents.

For the first joint family session with Isabel and her parents, the therapist introduced downward and upward spirals, with Isabel’s assistance. She accurately described a downward spiral at school, and parents were obviously pleased with her understanding of the content. When it was time to discuss examples from home, the therapist worked to keep the examples “light” as the father frequently highlighted examples where the children were misbehaving or not listening, stating that his children are “spoiled” compared to his childhood. The therapist validated this frustration, and highlighted the plan for FFT-CD to enhance communication, problem solving, and relationships at home. The therapist introduced the “Saying What You Liked” skill at the end of the session, using “thanks notes” (Asarnow et al., 2015) (instead of tokens) for each family member to “say what you like and appreciate.” The father led this task and family members enjoyed reading their notes aloud.

During the communication module, it became increasingly apparent through examples used in session that Isabel was having academic difficulties. In an individual session with the therapist, the parents continued to attribute this to Isabel not trying and a poor fit with teachers. As Figure 4 illustrates, a core downward spiral in this family involved Isabel’s difficulties with schoolwork, her parents’ unsuccessful attempts to motivate and correct her, and her increasingly negative perception of herself. The therapist raised the question of whether Isabel might have a learning problem, explaining that these difficulties may become more apparent as children become older and schoolwork becomes more difficult. The therapist and parents discussed the possibility of testing and ways that testing could be used to increase needed support at school and enhance Isabel’s school functioning.

Isabel requested that her little brother join the session, as some of the downward spirals involved him. Parents agreed, and he was invited into the session. Isabel taught him the first few skills that he had missed, and he was easily able to join the session and seemed to enjoy the silly practice examples. The family demonstrated much benefit from the communication skills, describing less conflict at home which they attributed to skills use, such as “Saying What You Didn’t Like” and using “thanks notes” to highlight helpful behaviors.

Middle Phase of Treatment

The next phase continued with communication, particularly active listening. The therapist worked with the parents to apply active listening skills in a way that was culturally sensitive, as the father initially expressed hesitation, believing it was most important for children to listen to their parents (not vice versa). The therapist highlighted how listening doesn’t necessarily mean that a person is agreeing with what is said or the course of action, it simply demonstrates that the other person was heard and can help children to feel valued and cared about, while also learning how to effectively explain their situations and ask for help when needed. Due to reported sleep and academic problems, the therapist decided to move the problem-solving module earlier in the standard session sequence. The family identified the problem that the family had all been going to bed late due to Isabel’s homework. All family members brainstormed ways to move the bedtime earlier, including eating dinner earlier, starting homework before dinner, and getting the “easy stuff” done before dinner and the “hard stuff” after dinner. The therapist threw some improbable ideas (e.g., do all homework in the early morning) into the list to highlight the need to brainstorm and not evaluate options. Parents and Isabel worked through the “plusses” and “minuses” of each option, and developed a plan. For example, the father agreed to try to get home earlier, the mother agreed to help Isabel organize her tasks into “easy” and “hard” after school so she could start with the “easy,” and Isabel agreed to use her communication skills if she felt overwhelmed (e.g., when mother was trying to explain a concept that Isabel did not get).

In the next session the therapist introduced fun activities. Isabel again invited her brother into this session, and the family developed a list of fun activities for the coming week. The therapist introduced the emotional thermometer to help the family track the mood shifts that occur during fun activities (and to aid Isabel in communicating about her anxiety related to school issues). The family reported back the next session about the activities they had done.

Final Phase of Treatment

Isabel demonstrated strong gains over the course of FFT-CD and the entire family described benefiting from learning the skills. In the final sessions, the therapist and family reviewed the skills that had been most helpful, discussed “early warning signs” of depression for Isabel and parents to be alert for, and developed a plan to use communication and problem-solving skills if they notice these signs. Isabel continued to struggle academically, but was in the process of getting tested at school, and her older cousin—a good student—was helping her with homework. Isabel appeared hopeful that things were going to get better and agreed that she would let her parents know if she felt stressed or any of the warning signs.

Results

Table 2 provides data on symptoms before and after treatment and at 4- and 9-month follow-ups. All three youth demonstrated sharp reductions in depressive symptoms and diagnostic remission from their depressive disorders. In two of the three cases there were sharp reductions in parent rating of depressive symptoms on the CDI and internalizing and externalizing scales on the CBCL. Global functioning scores increased markedly for these children, particularly by the 4- and 9-month follow-up points. Interestingly, although up to 3 booster sessions were offered during the 4 months following treatment, only one of the families requested and participated in a single booster session, and children continued to maintain or show additional improvements on most indicators.

Table 2.

Symptom Change Over Treatment and Follow-ups

| Case | Pre- treatment | Post- treatment | Follow-up 1 (4 months) | Follow-up 2 (9 months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Case 1 Adele | Depression Diagnosis | MDD/DD | None | None | None |

| CDRS-R Total Score | 56 | 26 | 22 | 20 | |

| Children’s Global Assessment Scale | 55 | 70 | 91 | 95 | |

| CDI Child/Parent | 4/21 | 0/9 | 1/7 | 0/12 | |

| CBCL Internalizing | 68 | -- | 58 | 56 | |

| CBCL Externalizing | 62 | -- | 49 | 51 | |

|

| |||||

| Case 2 Matthew | Depression Diagnosis | MDD | None | None | None |

| CDRS-R Total Score | 55 | 25 | 21 | 23 | |

| Children’s Global Assessment Scale | 55 | 60 | 75 | 68 | |

| CDI Child/Parent | 6/23 | 0/15 | 0/13 | 1/10 | |

| CBCL Internalizing | 73 | 68 | 63 | 68 | |

| CBCL Externalizing | 54 | 56 | 51 | 60 | |

|

| |||||

| Case 3: Isabel | Depression Diagnosis | MDD/DD | None | None | None |

| CDRS Total Score | 48 | 19 | 22 | 19 | |

| Children’s Global Assessment Scale | 58 | 75 | 80 | 85 | |

| CDI Child/Parent | 8/18 | 1/6 | 3/5 | 5/8 | |

| CBCL Internalizing | 75 | 50 | 50 | 56 | |

| CBCL Externalizing | 60 | 44 | 49 | 58 | |

Note. MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; DD = Dysthymic Disorder; CDRS-R (Child Depression Rating Scale – Revised) a score of 28 or lower indicates clinical recovery; CDI (Child Depression Inventory) a child-report score of 13 is the clinical cutoff; C-GAS (Children’s Global Assessment Scale) scores less than 70 are associated with mental health concerns; CBCL (Child Behavior Checklist) a t-score of 60 or greater is considered the borderline clinical range for Internalizing and Externalizing domains.

General Discussion

These three cases illustrate important attributes of the FFT-CD approach to treatment for depressed children. First, FFT-CD can be flexibly implemented within a range of family structures and include different family members. Second, while FFT-CD integrates CBT skills, it does this within the context of interpersonal interactions and processes. Third, the FFT-CD model and skills can be used to address the broad range of interpersonal challenges that depressed children frequently face, including academic challenges, peer difficulties, and family strains and tensions (e.g., parent conflict). Moreover, because the FFT-CD model focuses on the “family” and teaching skills for overcoming depression within a family context, this approach has potential for addressing depression in parents as well as children.

When choosing a family treatment, the question of who attends sessions can be a difficult conundrum. Who are the key players? Early family systems interventions (Minuchin, 1974) emphasized the importance of including all family members. We have found, however, in working with modern families with diverse structures, work demands, and complex schedules, such an insistence would largely preclude a family treatment approach for many families. Our pragmatic approach is one in which we would rather work with some family members than not do treatment unless everyone can be available. In addition, sometimes working with subsystems may be very effective, as children may respond differently to mothers vs. fathers. Downward spirals can occur with just two family members and a focus on those parties may be beneficial. As illustrated in our discussion of Matthew, the participants can vary over the course of treatment as schedules and treatment priorities evolve. At the beginning of treatment we were only able to engage Matthew and his mother; his father joined in during the middle of treatment; and as the parents decided to separate, we focused again on Matthew and his mother toward the end of treatment. In the case of Isabel, both parents were brought in early in treatment, as her father’s buy-in was essential to the family’s commitment to treatment; as his work schedule changed, later sessions were conducted with Isabel and her mother (and sometimes brother). The inclusion of siblings may also be dictated by logistical and/or clinical considerations. With both Adele and Matthew, younger siblings often attended sessions when childcare was not available; we were able to work with these very young children in session with minor adjustments. In the case of Isabel, inclusion of the brother was deemed appropriate when sibling interactions were central. In some cases, sibling conflicts are a frequent source of downward spirals and their resolution can be a key therapeutic goal; in other cases siblings provide an important source of support and help create many upward spirals. Thus, siblings can be incorporated into treatment on a case-to-case basis. At times absence of an important family member can impede solving important problems; but these times also offer opportunities to explore alternative coping strategies with family members who are in the session and to support families in using the skills outside of session to address issues with a family member who could not attend treatment. FFT-CD is a flexible model, giving therapists and families many options as treatment proceeds.

FFT-CD employs an interpersonal model of depression, emphasizing relationships and interpersonal interactions in mood regulation, with the primary treatment target of enhancing family interaction and support as a mechanism for supporting recovery. Although many skills common across CBTs for depression are interwoven within this model (e.g., mood monitoring, behavior activation, communication and problem-solving skills, and strengthening social skills and support systems), FFT-CD is not “doing CBT with the family.” Rather, FFT-CD aims to mobilize strengths within the family, change interactions and reinforcement patterns to promote skills and recovery, and enhance the family’s resources for communicating and problem-solving effectively with stresses that may trigger or maintain depressive cycles. Throughout treatment implementation, parents and children are talking to one another, trying new ways of communicating, and making plans and solving problems together.

Consistent with our developmental focus, FFT-CD is designed to meet the needs of children. Given that children’s primary supportive relationships are most often with family during the childhood period, FFT-CD teaches the child and his/her inner circle/family how to adapt to stressors and apply the skills to enhance well-being. Part of the “art” of implementing this intervention is to apply the model to the specific challenges families are facing. In the cases presented, these challenges involve associated syndromes, parental psychopathology, and external stressors. Interestingly, there are many parallels across these three cases. Each included all modules in the treatment and, largely, in the recommended order. In each, new skills were introduced, role-playing was used frequently, practice-at-home was completed. However, the central interpersonal processes were quite different. In the case of Adele, problems with anxiety- fueled negative family interactions leading to decreased support and tensions within the family; across development, anxiety is frequently comorbid with and tends to precede the onset of depression (Cole, Peeke, Martin, Truglio, & Seroczynski, 1998; Kovacs, Gatsonis, Paulauskas, & Richards, 1989). Within the FFT-CD model the family was able to observe which of the strategies for dealing with her anxious behavior were not working and try some new ones, including integrating exposure within the problem-solving training. With Matthew, withdrawal was more characteristic of the family interactions, where mother and/or child depressive symptoms sent each to their respective corners, lonely and sad. Supporting positive interactions became a central part of treatment, and family members were able to see how their withdrawal fueled mutual sadness. It is important to acknowledge that, unlike some forms of family treatment which would see the parents’ marital conflict as a central feature and address it directly, FFT-CD is focused on particular aspects of family functioning that directly impact this child and his/her symptoms. In the case of Matthew there was significant marital difficulty for which parents were referred to another provider. FFT-CD provided strategies for helping the parents cope with parenting their son during the fallout from their relationship demise. In the case of Isabel, the emphasis was on tense interactions associated with academic stress; enhancing the family relationships and directly focusing on turning negative spirals around schoolwork into more positive interactions were pivotal FFT-CD interventions. In all cases, the goal of the therapist was to help identify both negative and positive interactional patterns. Using the FFT-CD approach, we can help families develop strategies for catching downward depressive spirals triggered by stress and/or symptoms and mobilize family strengths to turn these spirals upwards and address challenges more effectively.