Abstract

Radionuclide therapy with nano-sized carriers is a very promising approach to treat various types of cancer. The preparation of radioactive nanocarriers can be achieved with minimum handling using a neutron-activation approach. However, the nanocarrier material must possess certain characteristics such as low density, heat-resistance, high metal adsorption, easy surface modification and low toxicity in order to be useful. Mesoporous Carbon Nanoparticles (MCNs) in which holmium oxide is formed in their pores by a wet-impregnation process are investigated as a suitable material for this application. Holmium (165Ho) has a natural abundance of 100% and possesses a large cross-section for capturing thermal neutrons. After irradiation of Ho-containing MCNs in a neutron flux, 166Ho, which emits therapeutic high energy beta particles as well as diagnostic low energy gamma photons that can be imaged externally, is produced. The wet impregnation process (16 w/w% Ho loading) is shown to completely prevent the leaching of radioactive holmium from the MCNs without compromising their structural integrity. In vitro studies showed that the MCNs containing non-radioactive holmium do not exhibit toxicity and the same formulation with radioactive holmium (166Ho) demonstrated a tumoricidal effect. Post-irradiation PEGylation of the MCN surfaces endows dispersibility and biocompatibility.

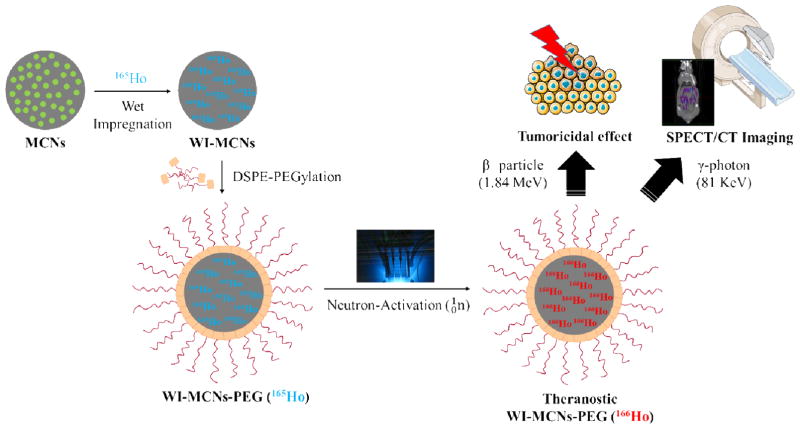

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

A variety of materials has been used in the design of nanocarriers for delivery of therapeutic agents to target organs and tissues. These agents include drugs, vaccines and radionuclides that emit particulate (α or β−) radiation. For the latter application, creating nanocarrier materials containing large amounts of therapeutic radionuclides can be hazardous to the personnel involved in this process. This can be avoided by incorporating a carefully selected stable nucleus into the nanocarriers and subsequently exposing them to a high flux density of thermal neutrons such as is found in a nuclear reactor. If the stable nuclei have a sufficiently large thermal neutron capture cross-section, they can be activated to therapeutic (i.e., tumor cell killing) radioactive nuclei. This neutron-activation approach allows the stable isotope-containing nanocarriers to be produced without constraints related to handling hazardous radioactive materials or short isotopic half-lives. The nanocarriers can be subjected to neutron irradiation just prior to the time of administration to patients, thus limiting the handling of radioactive materials by personnel. For such an application, the nanocarrier materials must be able to entrap significant amounts of the stable isotope, withstand the harsh conditions in the core of a nuclear reactor, retain the radioactive isotope produced following neutron irradiation to prevent accumulation of the radionuclide in non-target tissues due to leaching, be of relatively low density for facile administration by the intravenous route, and be non-toxic.

Mesoporous Carbon Nanoparticles (MCNs) have been widely studied for use in a variety of applications including as fuel cells, supercapacitors, gas storage devices and as catalysts, but only rarely for drug delivery applications. This is in contrast to other carbon-based materials such as carbon nanotubes, fullerenes, graphene oxide nanoplatelets and carbon nanodiamonds, all of which have been used as drug delivery vehicles [1–4]. Zhu et al. explored the possibility of using MCNs for chemo-therapeutic drug delivery by exploiting the hydrophobic nature, large surface area, easy surface modification and low toxicity profile of MCNs [5]. A product known as Carbon Nanoparticles Suspension Injection (CNSI®), which contain particles 150 nm in diameter, has been tested in human clinical trials and was approved as a lymph node tracer by the China Food and Drug Administration [6]. Interestingly, these carbon nanoparticles did not induce major toxicities or allergic reactions [7]. Here we report on the investigation of MCNs as a carrier of stable isotopes for subsequent conversion to radioactive isotopes following neutron irradiation. This neutron-activation approach allows the preparation of therapeutic radionuclides in carriers that can be targeted to tumors (requiring large amounts of radioactivity) with minimum handling by the operator. Among the potential candidates of stable neutron-activatable elements, holmium (165Ho) was chosen due to its high natural abundance (100%) and its large thermal neutron capture cross-section (64 b where 1 b = 10−24 cm2) for activation to 166Ho. This radioactive isotope of holmium decays by the emission of high energy β− particles (Emax= 1.84 MeV) and γ-photons (81 keV, 6.7% photon yield) with a relatively short half-life (26.9 h). These properties make 166Ho suitable as a ‘theranostic’ agent whereby the β− particles provide their tumor-killing radiotherapeutic function while the emitted γ-photons allows the biodistribution of 166Ho-labeled MCNs to be assessed noninvasively by SPECT/CT imaging (Fig. 1) [8, 9]. Indeed, a 166Ho/chitosan complex was formulated as a local tumor ablative agent in which their safety and efficacy were confirmed in a Phase IIb clinical study [10]. This formulation was approved under the brand name of Milican® in 2001 by the Korea Food and Drug Administration [11]. While this formulation demonstrated potential as a radiotherapeutic agent, it was produced by the cumbersome process of incorporating 166Ho into the formulation and not by neutron-activation of a 165Ho/chitosan complex.

Fig. 1.

Neutron-Activation and Theranostic Application of Mesoporous Carbon Nanoparticles (scheme produced using Servier Medical Art (www.servier.com)).

When considering materials as suitable carriers of neutron-activatable elements, one must take into account the loading capacity of the carriers for these elements as well as their stability following irradiation in a nuclear reactor where the neutron flux density is great enough to yield therapeutically-sufficient amounts of the activated radionuclide. Holmium encapsulated polymeric microspheres comprised of poly (L-lactic acid) have been used as carriers of neutron-activatable elements, and one such composition is currently in clinical trials for treating liver cancer [8, 12]. In spite of successful translation to the clinic, the biggest drawback of this formulation is degradation of the polymer by heat generated during the neutron-activation process. This can lead to premature leaching of the activated radionuclide which can result in radioactivity accumulating in non-target tissues after administration to a patient. In order to reduce this degradation, shorter neutron irradiation times must be used; however, this limits the total amount of radioactivity that can be produced to potentially sub-therapeutic levels.

Di Pasqua et al. explored the use of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) as a carrier for neutron-activatable isotopes for intraperitoneal administration [9]. Because of our interest in using neutron-activated nanocarriers as a means to treat various types of cancers by systemic administration, high specific activities (mCi of 166Ho mg−1 of nanocarrier) were required. This meant that long neutron irradiation times were needed to produce these high specific activities. Therefore, the nanocarriers required for this application need to have relatively high adsorption capacities for stable holmium and also need to be resistant to degradation in the relatively harsh nuclear reactor environment. In addition, it was desirable to avoid high-density nanocarriers to prevent settling of the particles during administration through an indwelling catheter. MCNs appeared to be an excellence choice as a nanocarrier for this theranostic application due to their desirable characteristics of lower toxicity than MSNs, heat resistance and high metal adsorption capacity [13–15]. Nanocarriers composed of mesoporous carbon were evaluated for their ability to serve as a suitable delivery vehicle for therapeutic radionuclides produced by neutron activation. Here we report that sufficient quantities of the stable isotope holmium (165Ho) could be incorporated into MCNs using a wet impregnation technique, and that minimal leaching of the radionuclide produced by neutron activation (166Ho) following irradiation in a nuclear reactor was observed. A novel NMR method was used to characterize the pore size distribution of the prepared MCNs. In addition, an in vitro cell-based assay was used to confirm that these stable holmium-containing MCNs did not induce cellular toxicity and that MCNs containing radioactive holmium demonstrated a sufficient tumor-killing effect. Furthermore, the surfaces of the MCNs were modified by the addition of a polyethylene glycol (PEG) moiety to allow them to be dispersed in physiological solutions for intravenous administration and as a means of improving their biocompatibility.

2. Experimental Section

2.1 Chemicals

Phenol, Pluronic® F127 (triblock copolymer consisting of poly(ethylene oxide)–poly(propylene oxide)–poly(ethylene oxide)), holmium (III) nitrate pentahydrate and holmium (III) oxide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Sodium hydroxide was obtained from Fisher Chemical (Fair Lawn, NJ). Formaldehyde (37%, ACS Reagent Grade) was received from Ricca Chemical (Arlington, TX). Holmium (III) acetylacetonate (Ho(AcAc)3) was acquired from GFS Chemicals (Columbus, OH). 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-ethanolamine-N-[methoxy (polyethylene glycol)-3000] (DSPE-PEG) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, Alabama).

2.2 Synthesis of MCNs

MCNs were synthesized from phenol formaldehyde resin by adopting the soft-template method of Zhao et al [16]. Briefly, phenol (0.6 g) was added to a mixture of formalin solution (2.1 mL) and sodium hydroxide solution (15 mL, 0.1 M), and stirred at 70 °C for 30 min at 360 rpm. A solution containing 0.96 g of Pluronic® F127 in 15 mL of Milli-Q water) was added to the reaction and the temperature was lowered to 66 °C. After 2 h, the mixture was diluted with 50 mL of Milli-Q water and the reaction was stopped when a reddish solid precipitate appeared. After measuring the volume of the suspension, a 3.16-fold excess of Milli-Q water was added. A hydrothermal reaction was then conducted at 130 °C for 24 h. After multiple washings with Milli-Q water, carbonization was performed at 700 °C under argon gas for 3 h after which time the final product (MCNs) was collected [16].

2.3 Wet impregnation on MCNs (WI-MCNs)

A wet impregnation (WI) approach was employed to produce MCNs from which entrapped holmium was less likely to leak. WI was accomplished by adding holmium nitrate pentahydrate (100 mg) and MCNs (10 mg) to 20 mL of ethanol and stirring for 24 h at room temperature. The suspension was then centrifuged at 2000 × g for 15 min and the supernatant was decanted to remove unbound holmium. The solids were held under vacuum at room temperature overnight; the temperature was subsequently raised to 400 °C for an additional 4 h to form holmium oxide. Any holmium oxide formed outside of the MCNs was removed by centrifugal filtration (Ultracel®, 50K MWCO) [17]. For a control study, Ho(AcAc)3 was loaded to MCNs by a physical adsorption method (MCNs-Ho(AcAc)3). This was accomplished by mixing 100 mg of Ho(AcAc)3 and 10 mg of MCNs in ethanol for 24 h at room temperature. After removing unbound Ho(AcAc)3, the mixture was dried in a vacuum oven overnight.

2.4 Surface modification of MCNs (MCNs-PEG)

The surfaces of these WI-MCNs were modified through non-covalent PEGylation by exploiting hydrophobic interactions between the MCNs and a phospholipid-based PEGylating agent. This was accomplished by adding DSPE-PEG to MCNs suspended in water and sonicating the suspension for 10 min.

2.5 Physicochemical characterization of MCNs

The hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of MCNs, WI-MCNs and WI-MCNs-PEG samples were measured using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS. Scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi S-4700) was used to obtain images of the particles. Elemental composition of samples was determined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS;) Kratos Axis Ultra DLD). As part of the sample preparation process, a powder form of the MCNs and WI-MCNs was pressed into an indium foil; interference from indium in the XPS analysis was normalized (Table 1). Powder X-ray powder diffraction (PXRD, Rigaku Multiflex X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ= 1.5418 Å)) was used to assess the structure of impregnated holmium oxide in the MCNs.

Table 1.

Elemental Analysis of MCNs and WI-MCNs by XPS.

| Element | MCNs | WI-MCNs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic % | Weight % | Atomic % | Weight % | |

| C | 94.2 | 92.4 | 79.2 | 61.9 |

| O | 5.8 | 7.6 | 19.1 | 19.9 |

| Ho | 0 | 0 | 1.7 | 18.2 |

2.6 Holmium loading on MCNs

The amount of holmium content was estimated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA; TA Instruments Q50). A 5 mg sample of WI-MCNs or MCNs-Ho(AcAc)3 was heated from 25 °C to 1000 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C minute−1. The holmium content of the MCNs was also determined by neutron-activation analysis utilizing the PULSTAR Reactor Facility at North Carolinas State University (reactor power = 1 MW; thermal neutron flux = 5.5 × 1012 neutrons cm−2 s). An ORTEC 42% high purity germanium detector system with a Canberra AFT research amplifier, multi-port II analog-to-digital converter and Genie 2000 MCA spectroscopy software were used to quantify the amount of 166Ho produced which was then used to calculate the amount of holmium (165Ho) in the sample.

2.7 Stability of MCNs following neutron irradiation

For assessing the stability and retention of holmium in the MCN formulations following neutron irradiation, samples were irradiated for 1, 5 and 10 h in the PULSTAR nuclear reactor, placed in centrifugal filter (Ultracel®, 50K MWCO) and centrifuged at 2500 × g for 20 minutes. The amount of radioactivity (166Ho) in the filtrate was measured using a γ-counter (PerkinElmer 2470 Wizard γ-counter).

2.8 Calculation of pore size distribution by NMR

The nanopore size, pore size distribution and pore volume were characterized using the NMR-based method of Wu et. Al [18]. The NMR measurements were performed on a 400 MHz (1H frequency) pulsed NMR system at room temperature. Approximately 20 mg of MCN and holmium-loaded MCN powder samples were loaded into a 4 mm spinner followed by addition of approximately 35 mg of deionized water. The spinner was then tightly sealed to prevent water loss due to evaporation. A Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) spectrum was obtained at ~7 kHz spinning by recording the free induction decay after a single 90-degree pulse (~5 μs). The last delay was set long enough (10 s, and T1 ~ 1.5 s) to ensure that the signal was fully recovered after each scan.

2.9 Evaluation of in vitro leaching

An in vitro leaching study was performed with 166Ho in which 200 μL of MCN-Ho(AcAc)3-PEG and WI-MCN-PEG samples (0.1 mg/mL) were placed in a dialysis cup (Slide-A-Lyzer MINI dialysis®, 3500 MWCO) which was suspended in 20 mL of Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) at 37 °C and shaken at 100 rpm (Thermo MAXQ 4450). A sample of the dialysate was collected at each time point (1, 2, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 36 h) and the holmium content was quantified in a γ-counter.

2.10 In vitro cytotoxicity and efficacy assessment of MCNs

The toxicity of each of the three MCN formulations was assessed in a human ovarian cancer cell line (A2780) using a CCK-8 assay kit (Dojindo Laboratories). The A2780 cells were cultured with RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The cells (5000 cells/well) were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h. Pre-determined amounts of the formulations were added to each well and cultured for 24, 48 and 72 h. After the formulations were removed and the wells were washed with PBS, the CCK-8 reagents (10 μL/well) were added. The cells were then incubated for 4 h and the absorbance at 450 nm was recorded with a plate reader (SpectraMax M5). To calculate the cell viability, the absorbance of each well was compared with an untreated group (control).

3. Results and Discussion

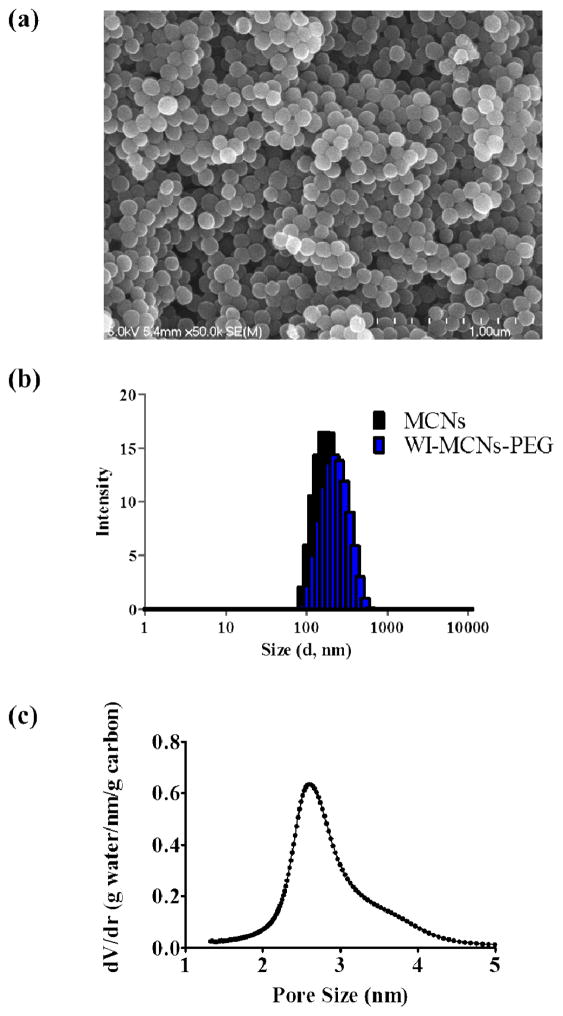

MCNs were successfully prepared using the soft template method [16]. Image analysis by SEM showed that MCNs were uniform and spherical in shape (Fig. 2a,b). The composition of MCNs was analyzed XPS and found to consist only of carbon (94.2%) and oxygen (5.8%) (Table 1). By dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potential measurements, the MCNs were shown to have an average diameter of 154 nm, almost neutral in surface charge (zeta potential = −0.37 mV) and to be monodisperse (PDI = 0.152) (Figure 1c). The Type IV isotherm curve obtained by nitrogen gas adsorption measurements was indicative of the mesoporous structure of the MCNs and, thus, were exhibited to have a large Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area (665.2 m2 g−1) (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of MCNs. a) SEM image of MCNs. b) The average particle size of MCNs and PEGylated MCNs by DLS. c) Pore size distribution of MCNs by NMR.

Fig. 3.

Change of physical characterization by WI a) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm of MCNs and WI-MCNs by BET. b) 1H MAS spectrum of water in MCNs and WI-MCNs.

Although the BET method has been widely used for characterization of porous carbon structures, the assumptions of BET theory have been questioned for micropores and mesopores because it tends to overestimate the specific surface area. Therefore, a newly developed NMR method, which is sensitive to pores less than ~3 nm, was used to characterize the pore size distribution of the MCNs [18, 19]. A typical NMR spectrum of a water/MCN mixture is shown in Fig. 3b. Intergranular water was used as the chemical shift reference (0 ppm) and the up-field peak at −1.5 ppm was from water inside the nanopores whose peak shape was used to derive the pore size distribution. The pore size was calculated from the nucleus-independent chemical shift (NICS) value by the following equation,

| (1) |

where A1, A2 and d0 are empirical parameters depending on the carbon material synthesis condition. Because MCNs were carbonized at 700 °C, which led to a lesser degree of graphitization and a smaller NICS effect, these parameters were recalibrated (scaled by 0.75 from a previous report whose carbon was prepared at 900 °C) so that the average pore size matched the value reported in the literature [16, 18, 20]. The nanopore volume per gram of carbon (excluding the intergranular pores) was calculated by the method of Xing et al.:

| (2) |

where Ap is the peak area of water in the nanopores, Atot is the total peak area, mw is the total water mass in the spinner, ρw = 0.9 g cm−3 is the nanoconfined water density and mMCN is the MCN mass in the spinner [18]. NMR analysis of water adsorption showed that the nanopore volume of MCNs was 0.69 cm3 g−1. The dominant pore size was 2.6 nm and the pore size distribution was narrow in that 95% of the pore sizes were between 2 and 4 nm (Fig. 2d). Intergranular pores were not considered because their contribution to the total surface area was negligible.

Initially, a hydrophobic form of holmium (Ho(AcAc)3) was used to load 165Ho into MCNs by physical adsorption. The amount of holmium loaded into MCNs was estimated by TGA, exploiting the fact that all of the carbon components were removed by pyrolysis between 400 °C and 600 °C, but holmium was retained even at 1,000 °C (Fig. 4). Holmium loading in the MCNs was determined to 6.96%. To maximize the loading of holmium as well as to prevent leaching, wet impregnation followed by a drying and calcination process was used to synthesize holmium oxide in the pores of the MCNs [17]. Although MCNs-Ho(AcAc)3 were able to retain 166Ho relatively well, intra-pore synthesis of holmium oxide by this technique was shown to essentially and completely prevent the leaching of radioactive holmium from these nanocarriers after they had been irradiated in the nuclear reactor for up to 10 h (Fig. 5). The particle size distribution and morphology of the WI-MCNs also did not change indicating that the structural integrity of the particles was not compromised by long irradiation times. The maximum loading of holmium by WI was determined to be approximately 14 w/w% by TGA and 18.2 w/w% by XPS (Table 1). The most accurate amount of holmium loading was determined by neutron activation analysis (NAA). After 165Ho was converted to 166Ho in the nuclear reactor, the amount of holmium in the MCNs was calculated from the quantity of radioactivity (166Ho) produced. NAA calculations determined that holmium loading in the MCNs was 5.34 w/w% and 16 w/w% by the physical adsorption method and WI, respectively. The PXRD pattern of WI-MCNs showed that holmium incorporation in MCNs resulted in significant reduction in signal intensity (Fig. S1). When it was contrasted with commercially purchased holmium oxide, several representative PXRD peaks of holmium oxide were absent in the WI-MCNs, which indicated crystalline structured holmium oxide was not formed outside of the mesoporous system. The total surface area of the MCNs was significantly reduced from 665.2 m2 g−1 to 368.6 m2 g−1 after the WI procedure. This is likely due to the holmium oxide particles occupying space in the pores of the MCNs (Fig. 3a). This was also evidenced by the NMR characterization. MCNs showed two 1H peaks where the upfield peak (at −1.5 ppm) was from water in the nanopores. However, the nanoconfined water peak was absent in the NMR of the holmium impregnated MCNs, indicating occupation of the nanopores by holmium (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 4.

Estimation of holmium loading on MCNs, MCNs-Ho(AcAc)3 and WI-MCNs by TGA.

Fig. 5.

In vitro leaching study of MCNs-Ho(AcAc)3-PEG and WI-MCNs-PEG.

For enhancing their biocompatibility and in vivo stability, surface modification of the WI-MCNs was accomplished by PEGylation reactions; both covalent and non-covalent methods were evaluated. Non-covalent PEGylation with DSPE-PEG was selected because it could be accomplished quickly with minimum handing. The hydrophobic portion (DSPE) of this phospholipid PEGylating agent rapidly associated with the hydrophobic MCNs after sonication for 10 minutes. WI-MCNs-PEG were shown to increase in diameter by approximately 20 nm and the surface charge changed from neutral to a negative zeta potential (−24.9 mV) while retaining monodispersity (PDI = 0.126) (Fig. 2c). To assess if the non-covalent PEG surface coating was stable following exposure to the neutron irradiation process, DSPE-PEGylated MCNs were irradiated in the nuclear reactor for 1, 5 and 10 hours. After a 1 h irradiation, no sign of loss of surface coating was observed, and the MCNs were as readily dispersed as they had been before neutron irradiation. However, when they were irradiated for 5 and 10 h in the nuclear reactor with the same neutron flux, the DSPE-PEG coating was apparently not stable as the particles could no longer be dispersed in aqueous media (Fig. 6a). The size and PDI of MCNs were not altered even after 10 h of irradiation (Fig. S2). If longer periods of irradiation are required to produce greater amounts of 166Ho that result in desorption of the DSPE-PEG coating, then performing PEGylation after the neutron-activation process is a possibility because the non-covalent PEGylation reaction can be accomplished within minutes (Fig. 7). This strategy was shown to be effective for WI-MCNs that had been irradiated for 5 and 10 h (Fig. 6b). Post-irradiation PEGylation provides an added advantage in that it allows the attachment of protein or peptide ligands that target tumors to the surface of the PEGylated MCNs.

Fig. 6.

Stability of DSPE-PEGylation after Neutron-Activation (a) Pre-Irradiation PEGylation (b) Post-Irradiation PEGylation.

Fig. 7.

Illustration of (a) Pre-Irradiation PEGylation and (b) Post-irradiation PEGylation approaches.

The cytotoxicity of MCNs was evaluated using a human ovarian cancer (A2780) cell line. The cells were exposed to three formulations (MCNs, WI-MCNs and DSPE-PEGylated WI-MCNs-PEG (WI-MCNs-PEG)), all containing the non-radioactive isotope of holmium (165Ho), for 48 h. As shown in Fig. 8a, none of these formulations induced any cytotoxicity at concentrations up to 100 μg mL−1. Thus, any tumor-killing activity by neutron-activated carbon nanoparticles would be due to the radiation and not be the result of chemical toxicity of the nanoparticle. After confirming the safety of non-radioactive MCNs, the efficacy of radioactive WI-MCNs-PEG that had been irradiated in a neutron flux for one hour using a longer incubation time (72 h) with the A2780 cells. While the non-radioactive (165Ho) MCNs did not induce cytotoxicity after a 72 h incubation, the radioactive (166Ho) MCNs showed a clear tumor-killing effect at the 24 h time point which significantly increased after longer incubation times (48 h and 72 h) (Fig. 8b). It has been well established that larger absorbed radiation doses induce a greater tumoricidal effect [21–24].

Fig. 8.

In vitro cell viability with formulations in a human ovarian cancer cell line (A2780). (a) Cytotoxicity of MCNs, WI-MCNs (165Ho) and WI-MCNs-PEG (165Ho). (b) In vitro efficacy of radioactive WI-MCNs-PEG (208 μCi at 100 μg MCNs/mL) vs. non-radioactive WI-MCNs-PEG. Groups were compared by two-way ANOVA (* for p<0.05 and † for Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise p<0.05 from Concentrations of MCNs) and each concentration was analyzed by independent t-test (δ for adjusted p<0.05 from 166Ho-MCNs-PEG (24 h), ε for adjusted p<0.05 from 166Ho-MCNs-PEG (48 h) and φ for adjusted p<0.05 from 166Ho-MCNs-PEG (72 h)).

The amount of 166Ho produced following irradiation of natural abundance holmium in a neutron flux was compared to the amount of other frequently employed therapeutic radionuclides (90Y and 177Lu) produced following neutron irradiation of yttrium and lutetium, respectively, under the same conditions. (Fig. 9 and Eqn. S1) [25]. While both 165Ho and 89Y have an isotopic natural abundance of 100%, 165Ho has much greater neutron capture cross-section than 89Y (64 b vs. 1.3 b) and a shorter half-life (27 h vs 64 h). While 176Lu has an approximately 40-fold larger neutron cross-section than 165Ho, its isotopic natural abundance is only 2.59% (mostly of Lu exist as 175Lu in the nature) and the half-life of 177Lu is also ~ 6-fold greater than 166Ho. Thus, the maximum amount of 166Ho that can be produced is much greater that the amount of 90Y and 177Lu, respectively, that can be produced when irradiating the same sample size under similar conditions.

Fig. 9.

Calculated mCi of radionuclides produced following irradiation of 1 mg of natural abundance holmium, yttrium and lutetium in a thermal neutron flux of 5.5 × 1012 neutrons cm−2 s as a function of time. The dotted lines represent the maximum amount of the individual radionuclides that can be produced under these conditions (radionuclide decay after the end of irradiation is not displayed). The thermal neutron capture cross-sections and half-lives were obtained from the Chart of the Nuclides (Knoll Atomic Power Lab) [26].

4. Conclusions

In summary, MCNs were investigated as a carrier material for neutron-activatable holmium for use in systemic radiation therapy. When compared to other nanoparticle systems that deliver therapeutic radionuclides, the neutron activation approach allows for easy production and adjustment of the radiation dose by using a neutron source with a different flux density (e.g., a higher power nuclear reactor), changing the time of irradiation, or increasing the loading of the stable isotope in the nanoparticle. MCNs were synthesized as spherical monodisperse particles with a diameter of approximately 150 nm. Their surface charge was neutral and they possessed a large surface area. A novel NMR method was employed for estimating the pore size distribution of the MCNs and revealed that these particles had an average pore size of 2.6 nm in diameter with a narrow pore size distribution. The wet impregnation loading method increased the loading capacity of the MCNs for holmium and resulted in no leaching of 166Ho after irradiation for 10 h in a nuclear reactor. The surfaces of the MCNs were PEGylated in order to enhance their biocompatibility and to make them suitable for intravenous administration. A non-covalent PEGylation method was selected over a conventional covalent PEGylation approach because the latter requires oxidation of MCN surfaces with strong acids and multiple washing steps. This lengthy process would not be practical if it were applied to post-irradiation surface modification of the MCNs due to the relatively short half-life of 166Ho. Finally, in vitro cytotoxicity studies employing a human ovarian cancer cell demonstrated that the non-radioactive MCNs were themselves not toxic, thus making them also suitable materials for non-radioactive therapeutic agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. A. Kumbhar and Dr. Carrie Donley at the Chapel Hill Analytical and Nanofabrication Laboratory (CHANL) at UNC for guidance in obtaining SEM and XPS data. We also appreciate S. Yusuf and Dr. F. Li at North Carolina State University (NCSU) for kind assistance with BET measurements and S. Lassell at the North Carolina State University Nuclear Reactor Program for neutron-activation analysis. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute through the Carolina Center of Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence (C-CCNE) Pilot Grant Program (1U54 CA151652-01), and a Research Scholar Grant (R03CA184394), the American Cancer Society (RSG-15-011-01-CDD), and a Dissertation Completion Fellowship from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ren J, Shen S, Wang D, Xi Z, Guo L, Pang Z, Qian Y, Sun X, Jiang X. The targeted delivery of anticancer drugs to brain glioma by PEGylated oxidized multi-walled carbon nanotubes modified with angiopep-2. Biomaterials. 2012;33(11):3324–3333. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang W, Guo Z, Huang D, Liu Z, Guo X, Zhong H. Synergistic effect of chemophotothermal therapy using PEGylated graphene oxide. Biomaterials. 2011;32(33):8555–8561. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang H, Hou L, Jiao X, Ji Y, Zhu X, Zhang Z. Transferrin-mediated fullerenes nanoparticles as Fe 2+-dependent drug vehicles for synergistic anti-tumor efficacy. Biomaterials. 2015;37:353–366. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volnova AB, Gordeev SK, Lenkov DN. Targeted Delivery of 4-Aminopyridine Into the Rat Brain by Minicontainers from Carbon-Nanodiamonds Composite. Journal of Neuroscience and Neuroengineering. 2013;2(6):569–573. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu J, Liao L, Bian X, Kong J, Yang P, Liu B. pH - Controlled Delivery of Doxorubicin to Cancer Cells, Based on Small Mesoporous Carbon Nanospheres. Small. 2012;8(17):2715–2720. doi: 10.1002/smll.201200217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye T, Xu W, Shi T, Yang R, Yang X, Wang S, Pan W. Targeted delivery of docetaxel to the metastatic lymph nodes: A comparison study between nanoliposomes and activated carbon nanoparticles. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2015;10(1):64–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu X, Lin Q, Chen G, Lu J, Zeng Y, Chen X, Yan J. Sentinel Lymph Node Detection Using Carbon Nanoparticles in Patients with Early Breast Cancer. PloS one. 2015;10(8):e0135714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mumper RJ, Ryo UY, Jay M. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication. 11. Vol. 32. Society of Nuclear Medicine; 1991. Neutron-activated holmium-166-poly (L-lactic acid) microspheres: a potential agent for the internal radiation therapy of hepatic tumors; pp. 2139–2143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Pasqua AJ, Yuan H, Chung Y, Kim JK, Huckle JE, Li C, Sadgrove M, Tran TH, Jay M, Lu X. Neutron-activatable holmium-containing mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a potential radionuclide therapeutic agent for ovarian cancer. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2013;54(1):111–116. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.106609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JK, Han KH, Lee JT, Paik YH, Ahn SH, Lee JD, Lee KS, Chon CY, Moon YM. Long-term clinical outcome of phase IIb clinical trial of percutaneous injection with holmium-166/chitosan complex (Milican) for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma. Clinical cancer research. 2006;12(2):543–548. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim SY, Suh M. Intellectual Property Business Models Using Patent Acquisition: A Case Study of Royalty Pharma Inc. Journal of Commercial Biotechnology. 2016;22(2):6–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smits ML, Nijsen JF, van den Bosch MA, Lam MG, Vente MA, Mali WP, van het Schip AD, Zonnenberg BA. Holmium-166 radioembolisation in patients with unresectable, chemorefractory liver metastases (HEPAR trial): a phase 1, dose-escalation study. The lancet oncology. 2012;13(10):1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wan L, Zhao Q, Zhao P, He B, Jiang T, Zhang Q, Wang S. Versatile hybrid polyethyleneimine–mesoporous carbon nanoparticles for targeted delivery. Carbon. 2014;79:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang C, Li Z, Dai S. Mesoporous carbon materials: synthesis and modification. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2008;47(20):3696–3717. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan A, Lau BW, Weissman BS, Külaots I, Yang NY, Kane AB, Hurt RH. Biocompatible, hydrophilic, supramolecular carbon nanoparticles for cell delivery. Advanced Materials. 2006;18(18):2373–2378. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang Y, Gu D, Zou Y, Wu Z, Li F, Che R, Deng Y, Tu B, Zhao D. A Low - Concentration Hydrothermal Synthesis of Biocompatible Ordered Mesoporous Carbon Nanospheres with Tunable and Uniform Size. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2010;49(43):7987–7991. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huwe H, Fröba M. Synthesis and characterization of transition metal and metal oxide nanoparticles inside mesoporous carbon CMK-3. Carbon. 2007;45(2):304–314. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xing Y-Z, Luo Z-X, Kleinhammes A, Wu Y. Probing carbon micropore size distribution by nucleus independent chemical shift. Carbon. 2014;77:1132–1139. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaneko K, Ishii C, Ruike M. Origin of superhigh surface area and microcrystalline graphitic structures of activated carbons. Carbon. 1992;30(7):1075–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forse AC, Griffin JM, Presser V, Gogotsi Y, Grey CP. Ring current effects: factors affecting the NMR chemical shift of molecules adsorbed on porous carbons. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2014;118(14):7508–7514. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elgqvist J, Timmermand OV, Larsson E, Strand SE. Radiosensitivity of Prostate Cancer Cell Lines for Irradiation from Beta Particle-emitting Radionuclide 177Lu Compared to Alpha Particles and Gamma Rays. Anticancer research. 2016;36(1):103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kassis AI. Seminars in nuclear medicine. Elsevier; 2008. Therapeutic radionuclides: biophysical and radiobiologic principles; pp. 358–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Y, Zhang L, Fan J, Jia R, Song X, Xu X, Dai L, Zhuang A, Ge S, Fan X. Let-7b overexpression leads to increased radiosensitivity of uveal melanoma cells. Melanoma research. 2015;25(2):119–126. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossini AE, Dagrosa MA, Portu A, Saint Martin G, Thorp S, Casal M, Navarro A, Juvenal GJ, Pisarev MA. Assessment of biological effectiveness of boron neutron capture therapy in primary and metastatic melanoma cell lines. International journal of radiation biology. 2015;91(1):81–89. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2014.942013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen JM, Ghannam M, Ayres JW. Neutron activation of iron tablets to evaluate the effects of glycine on iron absorption. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 1984;73(11):1529–1531. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600731108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baum EEM, Mary C, Knox Harold D, Miller Thomas R, Watson Aaron M. Nuclides and Isotopes : Chart of the Nuclides. 17. Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.