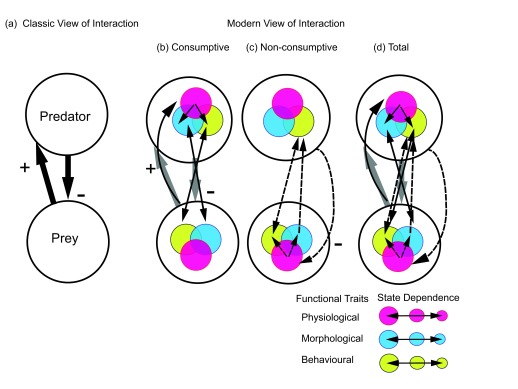

Figure 1. Depiction of classic and modern views of a predator–prey interaction.

A predator–prey interaction is represented as a module where consumptive effects are depicted by solid arrows and non-consumptive effects by dashed arrows. ( a) In the classic, generic view, predators have a negative consumptive effect on prey, and prey provide a positive nutritional benefit to predators. ( b– d) A modern view considers greater complexity due to interplay between predator and prey functional (physiological, morphological, and behavioral) traits. The predator–prey interaction is then decomposed into consumptive and non-consumptive effects. ( b) The success of the predator consumptive effect on prey is contingent on the alignment (double-headed arrows) between predator morphology (for example, gape width) and prey morphology (body size) and between predator behavior (for example, hunting mode) and prey behavior (for example, escape mode). The consumption of prey feeds directly to support predator physiological needs (the nutrient balance among maintenance, growth, and reproduction). The specific example here shows that physiology then directly determines predator morphology (for example, increased size) and behavior (for example, increased aggression), although behavior could also reciprocally determine physiology and morphology. ( c) A non-consumptive effect could arise when a predator has a negative effect on prey by eliciting a physiological stress response. Stress in turn alters prey physiology (for example, heightened metabolism), behavior (for example, alertness and vigilance), and morphology (for example, induction of escape morphology). ( d) The combination of consumptive and non-consumptive interactions leads to a total predator–prey interaction that becomes an adaptive game involving changes and feedbacks between predator and prey traits. The interactions are depicted in terms of predator and prey traits of a certain magnitude (size of circles). The nature of the game, however, can vary depending on the state of predator and prey (inset) in relation to each other, as determined by the magnitude of each other’s functional traits (size of the circles). Thus, the strengths of effects may depend on how the magnitude of physiological (for example, good condition [larger] or poor condition [smaller]), morphological (for example, large bodied [larger] or small bodied [smaller]), and behavioral (for example, bold [larger] or shy [smaller]) traits of predators and prey play off against each other in the adaptive, state-dependent game.