Abstract

Background

Although a mechanism for resolving ethical issues in patient care is required for accreditation of American hospitals, there are no formal qualifications for providing clinical ethics consultation (CEC), and there remains great variability in the composition of ethics committees and consult services. Consequently, the quality of CEC also varies depending on the qualifications of those performing CEC services and the format of CEC utilized at an institution. Our institution implemented an online CEC comment system to build upon existing practices to promote consistency and broad consensus in CEC services and enable quality assurance.

Methods

This qualitative study explored the use of an online comment system in ethics consultation and its impact on consensus building and quality assurance. All adult ethics consultations recorded between January 2011 and May 2015 (n=159) were analyzed for themes using both open and directed coding methods.

Results

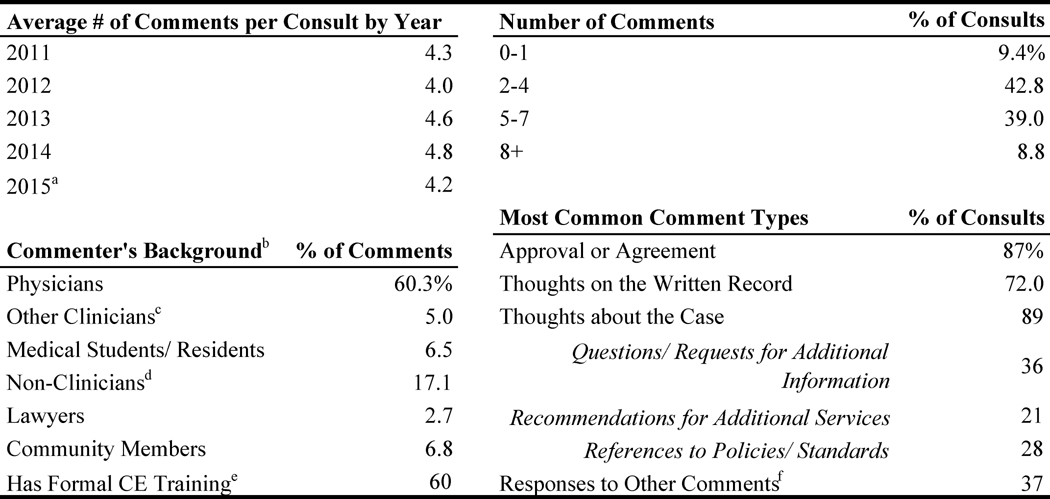

We found that comments broadly reflected three categories: expressions of approval/agreement (87% of consults), comments about the case (89%), and comments about the written record (72%). More than one-third of consults included responses to other comments (37%). The most common types of “comments about the case” included requests for additional information (36%), recommendations for additional services (21%), and references to formal policies/standards (28%). Comments often spanned multiple categories and themes. Comments about the written record emphasized accessibility, clarity, and specificity in ethics consultation communication.

Conclusions

We find the online system allows for broad committee participation in consultations and helps improve the quality of CEC provided by allowing for substantive discussion and consensus building. Further, we find the use of an online comment system and subsequent records can serve as an educational tool for students, trainees, and ethics committee members.

Keywords: clinical ethics, clinical ethics committees, quality improvement, graduate medical education

INTRODUCTION

In 1992, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO) issued standards that called for hospitals to “provide a mechanism for resolving ethics and value questions that arise in the care of patients” (JCAHO 1992). The commission did not specify how that “mechanism” should be organized or the minimum qualifications for those who would be “resolving ethics and value questions.” As a result, there is great variability in the composition of clinical ethics committees and consultation services.

A pivotal 2007 study by Fox and colleagues surveyed national practices in clinical ethics consultation (CEC) at 600 different hospitals and found that committees performing ethics consultation were composed of myriad professionals of varying backgrounds. Most CEC services relied on a small team of these individuals performing consultations (68%), as opposed to a full ethics committee (23%) or an individual (9%) (Fox et al. 2007).

In recent years, there has been growing concern about the qualifications (or lack thereof) of clinical ethics consultants. Only a minority of consultants have formal training through a fellowship or graduate degree in bioethics (Fox et al. 2007). This uneven level of preparation is worrisome, given that clinical ethics consults are “high-stakes,” involving critical decisions in times of uncertainty. In recognition of the fact that consultants play a significant role in the lives of patients and families and in shaping health care practices and institutional approaches to ethical dilemmas (American Society for Bioethics and Humanities [ASBH] 2011), some have argued that ethics consultation services should be professionalized. Others, fearing the consequences of standardization on a multidisciplinary and heterogeneous practice like clinical ethics, argue against a move to regulate ethics consultants (Bishop, Fanning, and Bliton 2009).

At our institution, we implemented an online clinical ethics consultation comment system in 2007 (Smith and Barnosky 2011). The goal of this novel approach to CEC is to build upon existing practices to promote consistency and broad consensus and enable quality assurance. The online ethics consult system provides a means of engaging all members of the committee in each consult “in real time” (within 24 hours of drafting the consultation report), thereby addressing the need for a timely response that is characteristic of ethics consults. Ethics committee members can give immediate input about consults, assuring that reasoned, valuable recommendations are provided. In addition, the online consults and discussions function as an educational tool for new members, students, and trainees.

In this article, we use the rich data afforded by our online comment system to describe and assess our experience with this approach to CEC.

METHODS

Setting

The University of Michigan Health System is a tertiary care medical center with 962 inpatient beds and includes the University of Michigan Medical School. The hospital has more than 45,000 admissions each year and approximately 70% of patients are referred from other regional hospitals.

Institutional CEC process

The institutional Adult Ethics Committee meets monthly and is a volunteer-based subcommittee of the Executive Committee on Clinical Affairs. Membership consists of a diverse range of clinicians (physicians, nurses, physician assistants [PAs], nurse practitioners [NPs], social workers, trainees, and others), as well as nonclinicians (health care attorneys, scientists, chaplains, community members, and others). Membership fluctuated over the course of the study period, with an average of 30 total members at one time. Approximately half of the committee’s members have some formal training in clinical ethics, although committee composition varied slightly over the study period. Formal training ranges from week-long intensive continuing education (CE) programs to graduate degrees in philosophy or bioethics.

Until 2015, this committee directly provided adult clinical ethics consultation services. Two volunteer committee members (one physician and one nonphysician) took calls for all CECs for a 2-week period on a rotating schedule. After conducting the initial consultation, a draft of the written consult with the recommendation(s) is posted to a secure Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant password-protected internal website, which automatically generates an e-mail alert to all committee members. All members are encouraged and expected to review consults “in real time” (i.e., within 24 hours of posting) so that their comments can be taken into consideration before the formal written consult is posted in the patient’s medical record and final recommendations are communicated to those who requested the consult. However, there is no quota or expectation for members to make online comments on specific cases. Participation in the consult is left to individual discretion. Comments are nested with the original consult and are cumulatively visible to all committee members. The committee reviews and discusses recent cases along with all posted comments at monthly meetings.

In 2016, our institution “professionalized” the clinical ethics consultation process by hiring a dedicated clinical ethicist who is supported by eight faculty ethicists, all of whom meet the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities (ASBH) criteria and are reimbursed for their service (ASBH 2011). This represents a core group with consistently more formal training in ethics than the prior volunteer-based model. The online consult system is still employed; however, given the change in CEC delivery, the data we use in this article are drawn only from the previous consultation model.

Data abstraction

The institutional review board evaluated this research protocol and deemed it exempt from formal review.

All consultation logs created between January 2011 and May 2015 are included in our analysis (n=159). Consultation logs were deidentified and each case was assigned a numerical code. Descriptive details were recorded, including who conducted the consultation, the primary issue identified by the consultant(s), the time spent on the consult, the number of comments, the commenters’ background(s), and the patient’s age and gender.

Data analysis

The consultation logs (case summaries, recommendations, and comments) were analyzed to assess how the online comment system was used by ethics committee members and to what extent it served the goals of consensus, quality assurance, and education.

During this initial examination, we noted patterns and themes in the text, and these were used to develop a set of broad comment categories: approval or agreement with the consultation, thoughts about the written record, and thoughts about the case. A coding framework was built within these categories using Dedoose, a qualitative data analysis software (SocioCultural Research Consultants 2016). This process was iterative; both open and directed coding approaches were used (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw 1995; Hsieh and Shannon 2005).

RESULTS

Our results offer a picture of the nature and extent of ethics consultation at a large academic hospital, and give us the opportunity to evaluate how our online comment system affects the quality of our CEC service and its role as an educational tool.

Consult descriptives

Table 1 describes the consultations included in the analysis. Consultations were documented by one consultant in 44% of cases (data unavailable regarding whether other engaged participants were simply not identified in the note). Occasionally, a consult would be performed by more than two consultants (15% of cases); for the most part, this occurred when trainees participated in the consult process. Time spent on the consultation was recorded for approximately 75% of consultations, which ranged in length from 30 minutes to 7 hours. More than half of consultations for which duration was reported lasted between 2 and 3.5 hours. Consultants identified a primary issue for each consultation; the most common primary issues were consent/competence (28% of cases), futility (23% of cases), and end-of-life care (16% of cases).

Table 1.

Consultation descriptives

| Primary Consult Issuea | # of Consultants | ||

|

|

|

||

| Advance Directives | 5.0% | 1 | 44.0% |

| Care Conference | 6.3 | 2 | 40.3 |

| Consent/Competence | 27.7 | 3–4 | 15.7 |

| End-of-Life Care | 15.7 | ||

| Family Disagreements | 13.2 | Length of Consult | |

|

|

|||

| Futility | 22.6 | 30 min – 1.5 hrs | 25.2% |

| Staff Relations | 3.1 | 2 – 3.5 hrs | 38.4 |

| Transplantation Issues | 0.6 | 4+ hrs | 11.3 |

| Utilization of Resources | 5.7 | Not Recorded | 25.2 |

The primary consult issue as identified by the original consultant; other issues are frequently present in a consult.

Slightly more consultations were conducted with female patients (57%). Additionally, consultations took place with patients across a range of ages from 18 to 102 years. Data regarding race, education, income, and insurance status were not reported in the online consultation system.

Table 2 provides descriptive details about the online comments entered by ethics committee members. Comments were provided on most consultations (153/159). The average number of comments per consult was four (representing roughly 13% of the committee membership), and this did not vary significantly over the analysis period. More than 80% of consultations included expressions of agreement or approval with the consultation. More than 70% of consultations included comments about the written consultation summary, and slightly fewer than 90% included comments or questions about the case details or issues. Nearly 40% of comments were responding to other comments previously posted. The majority of comments were from physician committee members.

Table 2.

COMMENT DESCRIPTIVES

Includes only consultations between January and mid-May

For 1.7% of comments, the commenter was not identified

Physician's Assistants, Nurse Practitioners, Nurses, Social Workers

Administrators and other Non-Clinical Professionals

i.e., formal CME training, such as the Kennedy Institute's Intensive Bioethics Course, or graduate study in philosophy or bioethics

Includes responses from the original consultant and other committee members

Approval and agreement

Most noticeably, the comment system enabled members to express approval or agreement with the analysis of the situation and the recommendations prior to the note being posted in the medical record. Approval comments, like those that follow, were very common.

180, Community member: I agree with the recommendations.

175, Medical student: I agree with the recommendations and look forward to discussing this complex case further at the next Committee meeting.

244, Attorney: Good job. This is an extremely difficult case.

As illustrated in these brief comments, an important function of the online system is to provide quick consensus around ethical analysis and recommendation prior to formal documentation in the medical record. Approval comments also often included compliments on specific aspects of the analysis or recommendations, highlighting key strengths in the case analysis or recommendations.

120, Nonclinician professional: Agree, and I also appreciate the discussion of futility. Not only is the narrower definition more conducive to effective communication with the family; it also maintains the important distinction between “no medical benefit” and a different kind of judgment, an ethical judgment, that the chance of benefit is not worth the risks or costs.

164, Physician: Thank you. Suicidality and DNAR [do not attempt resuscitation] are often challenging together, and you’ve nicely navigated this.

155, Nonclinician professional: Thanks for the thorough review and articulation of the ethical questions: decision-making capacity, surrogate decision-making, and goals of care.

Comments reflecting approval function more broadly to highlight when consultations are performed well and what high-quality consultation looks like to students and newer committee members.

Expressions of approval and agreement contributed to establishing consensus and assuring a quality consultation was completed. Expressions of explicit disagreement were rarely present. Instead, the comments expressing alternate perspectives were presented as “potential disagreement,” concern, requests for clarification, or sometimes as “playing the devil’s advocate.” These comments were more in the spirit of discussion or deliberation than explicit disagreement. In particular, these comments often included requests for additional information, references to hospital policies, recommendations for additional services/expertise, and deliberation on key issues.

Comments about the case

The online comment system provided an opportunity for discussion and deliberation of the issues and contextual features of challenging cases. Nearly one-third of consultations included at least one request for additional information on the case. These requests were related to different contextual features of a case, and they inquired about additional information such as pertinent medical details or aspects of the patient or family’s wishes or resources. Requests for additional information were sometimes, but not always, responded to within the comment system with follow-up comments from the original consultant (s).

245, Attorney: Did any family member(s) offer to assist in [the patient’s] care and demonstrate the ability to do so?

156, Social worker: I would be curious to know what type of insurance the patient has. If she has Medicaid perhaps she would be eligible for in-home support through the DHS Home Help Services program or the [State] Medicaid Waiver program.

252, Physician: Is his current mental status his “baseline” or worse because of withdrawal, sedation, change in usual surroundings, etc.? If he lived independently before his fall, seems like his cognitive status at least has the chance to improve, or at least improve enough so that he might be able to name someone he trusts to make medical decisions for him.

Committee members also use the comment system to suggest how to improve the consultation in real time. Given the makeup of the ethics committee and the importance of training medical students in clinical ethics, the opportunity to intervene and offer advice during the consultation process is an important function of the comment system.

185, Nurse practitioner: I think your plan sounds reasonable at this time. You mention the wife indicating that his decision is against their religion. If his religious beliefs are playing a role in him changing his mind, it may be helpful to involve spiritual care.

158, Physician: There are a number of ethical issues that could be discussed regarding this case, none of which have been elucidated. The first would be informed consent. It sounds like this patient was losing the ability to make decisions for himself while he was becoming hypotensive. Who was his surrogate decision-maker? Did he designate a DPOA [durable power of attorney]? What were his wishes surrounding end-of-life? Was there family around to help answer any of these questions? It sounds like the surgeons were operating under some sort of “presumed consent” or “best interest” criteria—for which a reasonable argument could be made … I may be reading this wrong, but it seems like this consult was called because the nurses involved disagreed with the management of the surgeons, but from what is described here it is hard to know if an ethical boundary was crossed.

170, Physician: You should clarify the concept of substituted judgment with the DPOA [person with durable power of attorney] and lay out all the evidence for how poorly he is doing. While ethically permissible to invoke the futility policy in this case, my point is that strategically it is better to have the DPOA come to the conclusion “on her own.”

The comment system provided some space for committee member deliberation and an ongoing conversation on key issues.

192, Physician: It seems rather straightforward that this patient should be DNAR [do not attempt resuscitation]. It is unclear to me why when the patient came to the ER he was queried again regarding resuscitation attempts. If the patient’s PCP [primary care provider] did the work to clarify with him that indeed he did not want aggressive resuscitation attempts it is troubling that he would be brought to the ER and then forced to try to communicate his wishes again (which sounds like a difficult enterprise.) The “conflict” between what he said in the ER regarding resuscitation (when it is likely he lacked decision-making capacity) and what he had clearly articulated to his PCP is only apparent and not real. I sometimes think that because the physicians are so scared of being considered paternalistic that they force these questions on patients as they are actively dying—and it is cruel.

[Another] Physician: It is typically policy to address code status at every admission. Often we (admitting and ER MD’s) reaffirm patient wishes if there is an apparent document, but often pts. do not have documented advanced directives or they are buried in the medical record. It is also true that pts. and family change their mind when readmitted for other conditions. So it is not necessarily cruel to ask pts about their wishes, especially since this was addressed before the patient was actively dying.

Medical student: Thank you for your comments. I understand that it’s routine to readdress code status but agree that in this case asking again unnecessarily muddied the waters because 1) the reason for readmission included altered mental status, likely uremia and 2) the quality of the prior code status discussion a week prior was much better (with PCP, more time spent explaining interventions involved, patient lucid). Perhaps high-quality code status discussions don’t need to be routinely revisited every admission (by new caregivers unknown to the patient) unless there is a good reason to do so. Also, when people are admitted with altered mental status, it may not be the best time to discuss code status unless they demonstrate capacity.

In these discussions, commenters also noted agreement with points raised in previous comments. Almost half of all consults contained at least one comment that noted agreement with a previous comment.

160, Physician: I agree with the above comments that seem to favor a time trial to get a better idea of her overall prognosis. Although quality of life is important it doesn’t seem she had overwhelming medical issues, she was able to work prior, and her psychiatric issues may be treatable.

129, Nonclinician professional: I would underline [previous commenter’s] implicit distinction between expressed wishes and true wishes. The challenge is to find some basis for judging that her true wishes are other than what she is expressing. If that can be done, then I would consider respecting those true wishes to be respect for autonomy.

The dialogue within the comment system also sometimes included follow-up statements identifying how comments resulted in changes to recommendations.

242, Administrator: The issue of nurses being afraid of bringing issues up is something I have worked with units on before. I usually work with a multidisciplinary team including the physician leaders, nursing leadership and staff to try and identify the underlying issues. One of the things I do in a situation like this is to consult with [staff person] in EAP [Employee Assistance Programs]. [They] have experience and expertise working especially with nurses who bring similar issues forward.

Physician: EAP is a good idea. We can discuss that resource with the nursing managers.

119, Nonclinician professional: Difficult case; reasonable response. You quote the article as saying, “Formal psychiatric diagnosis and treatment and ongoing psychological support is recommended for these types of patients.” It’s not clear if this patient had more than an evaluation for decision-making capacity. Would it be appropriate to recommend further psychiatric intervention?

Physician: I verbally recommended it to them this morning and they subsequently did consult psychiatry and they have left a preliminary note in the chart.

113, Physician: In response to [your] comments I modified recommendation #1, “There is no ethical obligation for the physicians to perform interventions that they judge to be causing more harm than good. If there is reasonable disagreement about what constitutes burdens, benefits, and standards of care, the patient should be referred to a physician who may consider performing the interventions in question.” [Per comments] I also recommended exploring the concept of goses [a Hebrew word signifying someone who is terminally ill and expected to die within 72 hours].

Comments about the written record

Many comments focused on the explicit written recommendations to be placed in the patient’s medical record. Comments sometimes focused on the organization of the analysis and recommendations, suggesting that more accurately categorizing different portions of the case summary or reordering recommendations would make the consultation clearer.

141, Physician: The discussion points that you have labeled 1) and 2) are not recommendations; they are part of the discussion and analysis. I would … label the final paragraph as your recommendation.

Some comments requested that the use of medical jargon and abbreviations be minimized to make consultations more understandable to committee members who did not have clinical training as well as to the requesting parties. Comments sometimes reminded consultants that portions of the medical record should be summarized versus copied and pasted into the consultation summary.

146, Physician: I am in agreement with your first set of conclusions and recommendations. Where possible though, in the future, for the benefit of those committee members who are not formally trained in either medicine or nursing, it is best to simplify medical terminology and avoid use of most acronyms … To the extent that we can foster the understanding of everyone of the committee (without compromising the medical context of the consult) we will be able to bring more of our members into the dialogue.

Comments also reminded consultants the recommendations should be clear and specific, and that language should consequently be precise. Occasionally this meant rewording phrases to be more succinct or using key phrases, such as “ethically permissible,” to frame recommendations. The focus on the written analysis and recommendations in the comments to some extent likely reflects the nature of the comment system itself: A written record is produced and therefore some comments are thus focused on how to improve writing. However, it is also possible and probable that the focus on language and communication is reflective of an effort in ethics consultation to define and practice a communication standard that emphasizes accessibility, clarity, and specificity.

130, Physician: As a [surgeon] it is my job to be nit-picky. It is never ethically permissible for a physician to not provide “care”. I know it is being used as shorthand for “invasive medical interventions” but being more precise with language serves a heuristic function for the medical students and junior residents who read our notes.

248, Nonclinician professional: This is more a matter of “application” of the recommendation, but I don’t know if we want the question to be permission to “withhold details of the diagnosis …” I think a way should be found to determine if the patient wants all medical information and decision-making to be in the hands of her family (or the person she designates). It should be clear that this means that information may be given to others rather than her, but I wouldn’t make the focus “may we not tell you what your diagnosis is?” The alternative of the patient being involved in the discussions should also be presented to be sure that she actually prefers the alternative of the family making decisions for her. I assume the hospitalist would be sensitive about this, but perhaps the recommendation should be worded a bit differently.

DISCUSSION

Consultation process

The results of our analysis suggest that the comment system is successful in generating broader committee participation in nearly all consultations (96%). Clinical ethics consultation frequently occurs independent of full ethics committees, and thus this model may have broad applicability (Bruce et al. 2011; Fox et al. 2007). Reliance on a single consultant or small consultation team may not allow for other important perspectives or ideas held by other committee members to be voiced (Aulisio, Arnold, and Youngner 2000; Rubin and Zoloth 2004). Some advocate that clinical ethics consultations are best performed by ethics committees, as they offer the opportunity to consider a larger breadth of opinions and perspectives when a difficult case is being discussed (Rubin and Zoloth 2004). However, such a model is frequently impractical. The online system makes it possible to benefit from broader participation and engage and incorporate the expertise of the entire committee “in real time” through the use of an electronic forum for case discussion and deliberation.

An important contribution of the use of an online comment system is its ability to elevate the process of clinical ethics consultation from either a small consultant team model or full ethics committee model to one that incorporates the strengths of both. By including the voices of multiple members of the ethics committee through online commentary, the online comment system sustains a distinctly interdisciplinary service without placing extraordinary demands on those whose work does not take place primarily in the hospital setting, such as lawyers, community members, administrators, and other academic experts. These observations suggest that an online comment system is an effective addition to ethics consultation services in hospitals and that it can facilitate engaged, sustained involvement of committee members throughout the consultation process.

Many consults that are relatively straightforward for those with experience and training in clinical ethics may be difficult for newer and less seasoned members. The ability of multiple members to offer quick agreement with the proposed recommendations demonstrates how consensus can be established efficiently, benefitting all involved stakeholders. This particularly benefits inexperienced consultants, who can obtain important just-in-time affirmation of their analysis and recommendations from more experienced committee members.

Quality assurance

Institutions seeking to provide quality ethics consultation at all hours but also to retain the benefits of committee discussion and consensus may struggle to schedule ad hoc meetings and provide timely advice. The comment system allows members of the committee an opportunity to voice assent immediately after a consultation is performed, wherever committee members may be located. Fundamentally, it functions as an effective form of surveillance of ethics-related discourse. This allows consult service leadership to vet all services provided even when not personally involved in the case and also ensures that even experienced high-volume consultants are not making decisions in a vacuum. In addition, its primary role in quality assurance potentially protects this electronic venue from the legal discovery process.

While consensus itself is not a metric of a successful or effective ethics consultation, it is reasonable to suggest it is an important condition for quality assurance purposes (Moreno 1988). The subsequent relevance of a process that allows for demonstrating consensus is a tool to help assess whether proper analysis and recommendations have been rendered. Agreement and approval comments also often included positive feedback on specific aspects of the analysis or recommendations, making it particularly clear how consensus comments relate to the goal of quality assurance (Agich 2005; Aulisio et al. 2000). The use of the comment system to voice alternate perspectives or reflect on other potentially important details or issues present in the case not only brings to bear the strengths of a committee model, but further helps to assure that thorough and consistent ethics consultation is performed and that dissent, if present, is considered.

Further, comments about the contextual features or issues present in a case demonstrate reflection about all elements of proper ethics consultation: the identification of the ethical question, the consideration of relevant consultation specific information, an appropriate ethical analysis, conclusion, and recommendations (Pearlman et al. 2016). For example, clarification comments or recommendations for additional services provide clear evidence of how the comment system can improve the performance of ethics consultation. Pearlman and colleagues (2016) suggest that quality ethics consultation is informed by relevant consultation-specific information, such as patient preferences and medical and social facts, and that the appropriate sources and processes have been used to obtain these facts. Requests for additional information or details ensure that consultants have not overlooked potentially important elements, and suggestions for additional services enable the ethical analysis and recommendations to reflect the best possible range of available and appropriate options.

The 2013 Quality Attestation Presidential Task Force of the ASBH outlined a means for regulating and certifying qualified ethics consultants with “diverse opportunities to demonstrate competence” (Kodish et al. 2013, 30). With pilot evaluations recently completed (Fins et al. 2016), this proposed two-step process of portfolio review and oral examination highlights key features for ensuring excellence in ethics consultation, such as experience with ethics consults, familiarity with fundamental ethics cases and concepts, and real-time reasoning through the ethics consultation process. This process is very useful in establishing whether individuals can reliably perform quality ethics consultation, but is distinct from establishing whether a particular consultation is of high quality. The Ethics Consultation Quality Assessment Tool (ECQAT) also strives to assess these key ethics consultation skills, evaluating whether a particular consultation meets quality standards (Pearlman et al. 2016). However, both these metrics of quality assurance are retrospective in nature; the unique value of an online comment system is that it allows for the assessment of ethics consultation in real time, improving and assuring quality in the index case.

The comment system helps to clarify the reasoning processes used by consultants and the justifications offered for their recommendations; it also provides the opportunity to suggest alternative approaches or resources. We recognize, however, that the system is not the same as direct observation of consultants at work, and that determining the quality of a consultant’s work—including skillful mediation and communication—cannot be fully assessed by review of the written record. However, despite its inherent limitations, we have found the system offers a valuable way of promoting the quality of the consults we provide.

Education

Online comments also provide an invaluable opportunity for educating committee members and trainees. Training newer members of ethics committees—including medical students and residents—is an important goal of hospital ethics committees (Fox et al. 2007; McGee et al. 2002). Consult documentation and the ensuing discussions and comments are helpful for members with limited experience in ethics consultation who will subsequently participate in the consultation service. These written records serve as an educational tool demonstrating how to summarize relevant information and employ appropriate ethical reasoning to convey a range of ethically appropriate options.

The comment system allows for the involvement of more experienced or formally trained members to offer a level of supervision with their feedback and assist with consults in ways that would otherwise only be available retrospectively. In addition, newcomers to the institution with prior clinical ethics experience may utilize this discussion forum as a metric to learn the “culture” of the institution’s clinical ethics service.

The medical school also runs a unique co-curricular optional Path of Excellence that allows students to gain considerable experience in clinical ethics.1 In addition to ethics education in the form of didactic talks and small-group sessions, students are required to rotate on the ethics consultation service and gain expertise in performing consults. The consultation database and comment system is an invaluable cache of prior experience from which to generate didactic materials and illustrative case examples, often with varying perspectives. This is especially important since ethics consults vary in frequency and rotating students “on call” may not be involved in enough consults for adequate training. Having students participate in the online comment and review process allows greater exposure to consultations.

Given that few clinical ethics consultants across the nation have completed a graduate degree or fellowship in bioethics, and many lack formal, direct supervision when learning how to perform ethics consultation, the applicability of our paradigm to other clinical settings appears valid (Fox et al. 2007).

Documentation

Recent efforts for credentialing and quality attestation in ethics consultation have hinged on the written record produced during an ethics consultation (Kodish et al. 2013; Pearlman et al. 2016). These efforts suggest that the written record is at the very least an appropriate source for determining whether quality clinical ethics consultation is being performed. Pearlman and colleagues focus on providing a holistic score as to whether the consultation performed is adequate. Many of their guidelines for assessing whether the consultation is adequate describe a written record that is “complete, clear, consistent, and appropriate in subject matter and level of detail” (Pearlman et al. 2016, 10). Without a clear written record, the quality of ethics consultation is difficult to ascertain.

The written record, however, is not simply evidence of whether a quality consultation has been performed but is also a significant product of the consultation itself. Consult notes are placed in the medical record and serve to educate the treating team(s) about the ethical reasoning and judgment relevant to the issues involved (Dubler et al. 2009). Articulate and easily understood language is vital to conveying how physicians and other clinicians should proceed clinically, and why a particular path is ethically permissible; unlike in-person conversations, chart notes are a resource that the treating team or teams can refer back to as they continue to care for present as well as future patients.

Accessibility, clarity, and specificity in communication are necessary for performing (and later demonstrating) quality clinical ethics consultation. Consequently, comments that reflect an effort to improve the written record reflect broadly the goals of quality assurance and educating members of the ethics committee and hospital staff on ethical reasoning.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

While the comment system provides a number of demonstrable benefits to the clinical ethics consultation process, there are inherent limitations to its role. First, committee members responding in the comment system are constrained to interpreting the information provided by the original consultant. However, the comment system does allow other committee members to point out information that may not have been taken into account based in the consultants’ summary and recommendations.

Assessments of consensus—and the benefits of this consensus—within the comment system should also be interpreted with some caution. For example, a lack of consensus or agreement comments might result when committee members had little to add or few had time to read the consultation, but does not necessarily reflect disagreement with the recommendations. On the other hand, consensus may still be misguided if those comments are from members who are less experienced or are not formally trained in CEC. However, because the system allows more experienced members to participate in all consultations, consensus regularly included the voices of long-standing committee members, those with formal training in CEC, and the committee co-chairs.

There are also some limitations to our observations. The setting of a large tertiary care academic hospital with a diverse ethics committee is distinct; institutions with a fundamentally different structure or that have a lower volume of consultation requests may not find an online comment system as beneficial in this format.

Our observations are limited by the data available to us. For example, we have no record of how often consults were accessed and read. We noted the relatively low percentage (13%) of members who commented on individual cases but, lacking data on number of “reads” for a case, we are uncertain how to interpret the proportion of members who provided comments. We speculate that members likely did not see a need to comment if they did not have substantive feedback that would augment what had already been documented in the consult or prior comments, and that this low number reflects an aversion to repetition more than lack of participation. Moreover, comments that were perceived as “less urgent” might have been reserved for monthly meeting discussions rather than electronically posted. We are now tracking this figure prospectively, and are interested in comparing our data to other centers with similar systems.

We also could not measure the timeline of comment entries. Finally, although we are able to ascertain many instances in which changes to the recommendations were made based on follow-up comments by the original consultant, we were not able to capture all of these instances within the comment system. Moving forward, the new software currently in use allows us to address some of these data collection limitations.

Future research should consider exploring how members and trainees perceive the online comment system, particularly as an educational resource. It would also be interesting to see whether nonphysicians and trainees feel more comfortable commenting online rather than in person, reflecting the perception of a professional hierarchy within the medical system. Additionally, future research should explore how this process could be adapted to serve institutions with lower volumes of consultation requests or those with differently structured service delivery. Recent research has considered how telemedicine can augment ethics consultation in rural areas (Kon and Walter 2016); it is possible that a secure online system could also allow commentary across institutions. As we expand our new clinical ethics program, the evolution of the role of the online consultation system will also benefit from renewed scrutiny; a project examining this shift and its impact on the quality of consultation services is already underway.

CONCLUSION

The use of an innovative online comment system within a dynamic clinical ethics consultation service efficiently facilitates broad committee participation and consensus building. The electronic venue creates a meaningful and substantive discussion and deliberation of relevant case details and recommendations. This process helps to improve the overall quality of clinical ethics consultation by safeguarding that appropriate details have been considered and recommendations reflect the input of diverse committee members. The comment system may also be used as a tool to provide training and education. The system encourages reflection on the written record produced in ethics consultation, with a focus on ensuring that case summaries, ethical analyses, and recommendations are accessible, clear, and specific.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Renee Anspach for helpful feedback and comments throughout this project. We also thank the Adult Ethics Committee at the University of Michigan for making these data available for analysis.

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in AJOB Empirical Bioethics on May 30, 2017, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23294515.2017.1335808.

FUNDING

The first author acknowledges fellowship support she received through an NICHD training grant to the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan (T32HD007339).

Footnotes

University of Michigan Medical School: Ethics Path of Excellence (https://medicine.umich.edu/medschool/education/md-program/curriculum/longitudinallearning/paths-excellence/ethics-path-excellence).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K. Hauschildt analyzed the data, interpreted findings, and drafted the article. T. K. Paul assisted with drafting the article. R. De Vries assisted with interpreting the findings and reviewed drafts of the article. C. J. Vercler provided scientific input and reviewed drafts of the article. L. B. Smith provided scientific input and reviewed drafts of the article. A. G. Shuman coordinated the study, interpreted findings, reviewed drafts of the article, and responded to reviewer comments.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest regarding the content of this original article.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This study was approved by the institutional review board(s) at the University of Michigan Medical School.

References

- Agich GJ. What kind of doing is clinical ethics? Theoretical Medicine. 2005;26:7–24. doi: 10.1007/s11017-004-4802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Society for Bioethics and Humanities. Core competencies for health care ethics consultation. 2. Glenview, IL: ASBH; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aulisio MP, Arnold RM, Youngner SJ. Health care ethics consultation: Nature, goals, and competencies. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;133(1):59–69. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop JP, Fanning JB, Bliton MJ. Of goals and goods and floundering about: A dissensus report on clinical ethics consultation. HEC Forum. 2009;21(3):275–91. doi: 10.1007/s10730-009-9101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce CR, Smith ML, Hizlan S, Sharp RR. A systematic review of activities at a high-volume ethics consultation service. Journal of Clinical Ethics. 2011;22(2):151–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubler NN, Webber MP, Swiderski DM, et al. Charting the future: Credentialing, privileging, quality, and evaluation in clinical ethics consultation. Hastings Center Report. 2009;39(6):23–33. doi: 10.1353/hcr.0.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson M, Fretz RI, Shaw LL. Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fins JJ, Kodish E, Cohn F, et al. A pilot evaluation of portfolios for quality attestation of clinical ethics consultants. American Journal of Bioethics. 2016;16(3):15–24. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2015.1134705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox E, Myers S, Pearlman RA. Ethics consultation in United States hospitals: A national survey. American Journal of Bioethics. 2007;7(2):13–25. doi: 10.1080/15265160601109085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Comprehensive accreditation manual for hospitals, section RI. 1.1.6.1. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: JCAHO; 1992. Patient rights. [Google Scholar]

- Kodish E, Fins JJ, Braddock C, III, et al. Quality attestation for clinical ethics consults: A two-step model from the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities. Hastings Center Report. 2013;43(5):26–36. doi: 10.1002/hast.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon AA, Walter RJ. Health care ethics consultation via telemedicine: Linking expert clinical ethicists and local consultants. AMA Journal of Ethics. 2016;18(5):514–20. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.5.stas1-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee GE, Spanogle JP, Kaplan AL, Asch DA. Successes and failures of hospital ethics committees: A national survey of ethics committee chairs. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 2002;11(1):87–93. doi: 10.1017/s0963180102001147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JD. Ethics by committee: The moral authority of consensus. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy. 1988;13:411–32. doi: 10.1093/jmp/13.4.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman RA, Foglia M, Fox E, Cohen J, Chanko BL, Berkowitz K. Ethics consultation quality assessment tool: A novel method for assessing the quality of ethics case consultations based on written records. American Journal of Bioethics. 2016;16(3):3–14. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2015.1134704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin SB, Zoloth L. Clinical ethics and the road less taken: Mapping the future by tracing the past. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics. 2004;32:218–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2004.tb00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LB, Barnosky A. Web-based clinical ethics consultation: A model for hospital-based practice. Physician Executive Journal. 2011;37(6):62–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. Dedoose: Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data, Version 7.0.23. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2016. [Google Scholar]