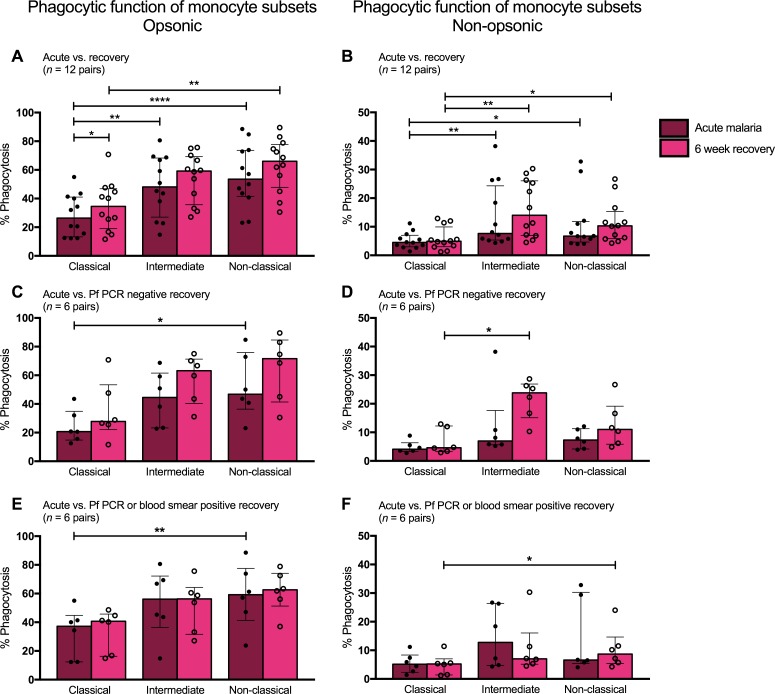

Figure 6. Intermediate and nonclassical monocytes display greater phagocytic function compared with classical monocytes.

(A) Opsonic phagocytic function of the three monocyte subsets from acute malaria (AM) and 6-week recovery PBMC samples (n = 12 pairs) in the presence of Ghana14 IEs opsonized with heat-inactivated pooled plasma from malaria-immune Kenyan adults. (B) Nonopsonic phagocytic function of monocyte subsets from AM and 6-week PBMC samples (n = 12 pairs) in the presence of Ghana14 IEs opsonized with heat-inactivated plasma from a malaria-naive North American. (C) Opsonic phagocytic function of monocyte subsets from AM and 6-week PBMC samples (n = 6 pairs) from a subset of children who were P. falciparum PCR negative at 6 weeks. (D) Nonopsonic phagocytic function of monocyte subsets from AM and 6-week PBMC samples (n = 6 pairs) from a subset of children who were P. falciparum PCR negative at 6 weeks. (E) Opsonic phagocytic function of monocyte subsets from AM and 6-week PBMC samples (n = 6 pairs) from a subset of children with asymptomatic P. falciparum infection at 6 weeks (defined by positive blood smear or P. falciparum PCR). (F) Nonopsonic phagocytic function of monocyte subsets from AM and 6-week PBMC samples (n = 6 pairs) from a subset of children with asymptomatic P. falciparum infection at 6 weeks (defined by positive blood smear or P. falciparum PCR). Differences between AM and 6-week PBMC samples analyzed by Wilcoxon matched-pairs rank test. Differences among subsets analyzed by Friedman test with multiple comparisons. Data shown are medians with interquartile ranges. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.