Abstract

Background

To maximize the translational utility of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), the ability to precisely modulate the differentiation of iPSCs to target phenotypes is critical. Although the effects of the physical cell niche on stem cell differentiation are well documented, current approaches to direct step-wise differentiation of iPSCs have been typically limited to the optimization of soluble factors. In this regard, we investigated how temporally varied substrate stiffness affects the step-wise differentiation of iPSCs towards various lineages/phenotypes.

Methods

Electrospun nanofibrous substrates with different reduced Young’s modulus were utilized to subject cells to different mechanical environments during the differentiation process towards representative phenotypes from each of three germ layer derivatives including motor neuron, pancreatic endoderm, and chondrocyte. Phenotype-specific markers of each lineage/stage were utilized to determine differentiation efficiency by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and immunofluorescence imaging for gene and protein expression analysis, respectively.

Results

The results presented in this proof-of-concept study are the first to systematically demonstrate the significant role of the temporally varied mechanical microenvironment on the differentiation of stem cells. Our results demonstrate that the process of differentiation from pluripotent cells to functional end-phenotypes is mechanoresponsive in a lineage- and differentiation stage-specific manner.

Conclusions

Lineage/developmental stage-dependent optimization of electrospun substrate stiffness provides a unique opportunity to enhance differentiation efficiency of iPSCs for their facilitated therapeutic applications.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13287-017-0667-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Induced pluripotent stem cells, Mechanobiology, Differentiation, Substrate stiffness

Background

The derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has revolutionized the field of personalized regenerative medicine by offering a potentially unlimited cell source to treat a variety of diseases [1]. In addition to their clinical potential, human iPSCs provide opportunities to develop patient-tailored in vitro models for pathogenesis and toxicity studies [2–4]. To fully realize these diverse potentials, it is important to efficiently control iPSC behavior, such as self-renewal and differentiation [5]. Specifically, the ability to precisely modulate the lineage/phenotype-specific differentiation of cells is critical for minimizing safety concerns of iPSCs in vivo (e.g., tumorigenesis and teratoma formation) [6, 7] or generating physiologically relevant tissue models in vitro [2]. Similar to embryonic stem cells, iPSCs can be directed to differentiate towards various lineages/cell phenotypes by activating specific signaling pathways [7–9]. In particular, the sequential application of biochemical factors derived from embryonic development provided a foundational backbone to guide iPSC differentiation [10]. However, such protocols typically discount the role of the underlying physical factors, such as morphology, surface chemistry, and mechanical properties of substrates, which also affect differentiation efficiency.

In this regard, our previous studies have demonstrated the significant role of substrate stiffness on the spontaneous or directed early-stage differentiation of iPSCs [11, 12]. Electrospun nanofibers were used as a platform to control the stiffness of cell-adherent surfaces without affecting other physical parameters (e.g., surface chemistry, topography, availability of adhesion sites) to elicit mechanomodulated behaviors of iPSCs. The differences in substrate stiffness exerted profound effects on cell colony formation, resulting in various degrees of cell-material and cell-cell interactions, and ultimately the differentiation efficiency towards both mesendodermal and ectodermal lineages. In another study, we also showed the effects of substrate stiffness on the morphology of adult stem cells and their subsequent differentiation to end-phenotypes [13]. Based on those results, in this study we investigated the previously unexplored role of temporal changes in substrate stiffness on iPSCs throughout the course of differentiation. A well-characterized iPSC line [11] was differentiated towards representative phenotypes from each of the three germ layer derivatives while their substrate stiffness varied at each differentiation stage. Our results demonstrate that a sequential application of mechanically distinct electrospun substrates during the differentiation processes can enhance the differentiation efficiency of iPSCs in a lineage- and developmental stage-specific manner. This novel finding provides insights into the understanding of the mechanoresponsiveness of cell development and it establishes a platform to enhance directed differentiation of iPSCs by temporal modulation of the mechanical microenvironment.

Materials and methods

Electrospun substrate synthesis and characterization

Electrospinning conditions were optimized for 8 wt.% poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL; Sigma-Aldrich, MO) dissolved in 5:1 trifluoroethanol-water and 5 wt.% polyether-ketone-ketone (PEKK; Oxford Performance Materials, CT) dissolved in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFP; Oakwood Products Inc., SC) to synthesize nanofibrous substrates with approximately 450-nm fiber diameter. To obtain the same surface chemistry for cell adhesion, the substrates were air plasma-treated and collagen-conjugated as previously described [12] (see Additional file 1 for chemical characterization of the scaffolds). The elemental composition of the electrospun substrate surface was characterized by x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) using a Kratos AXIS ULTRADLD XPS system equipped with an Al Kα monochromated x-ray source and a 165-mm mean radius electron energy hemispherical analyzer. The substrates were also mechanically characterized using atomic force microscopy (AFM) as previously described [12]. The surface area was measured by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method using nitrogen adsorption.

Cell culture and differentiation

A well-characterized human iPSC line, derived from BJ-2522 human neonatal foreskin fibroblast cells transfected with OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 as previously described [11], was maintained on Geltrex®-coated tissue culture polystyrene plates (TCPS) in mTeSR™1 medium (Stemcell Technologies, Canada) in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were passaged from tissue culture plates for each stage of differentiation using 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Life Technologies, NY). A ROCK inhibitor, Y-27632 (EMD Millipore, MA), was used at 10 μM concentration to enhance cell survival after seeding onto electrospun substrates or TCPS. After overnight incubation, the Y-27632 was removed and fresh media supplemented with lineage- and stage-specific growth factors was added. Media was exchanged daily unless otherwise noted. To examine the effects of temporally varied electrospun substrate stiffness on the differentiation of iPSCs, step-wise differentiation protocols for motor neuron, pancreatic endoderm, and chondrocytes were utilized. Details of the differentiation protocols and analysis of gene and protein expression at each differentiation stage can be found in the supporting information (see Additional file 2).

Results and discussion

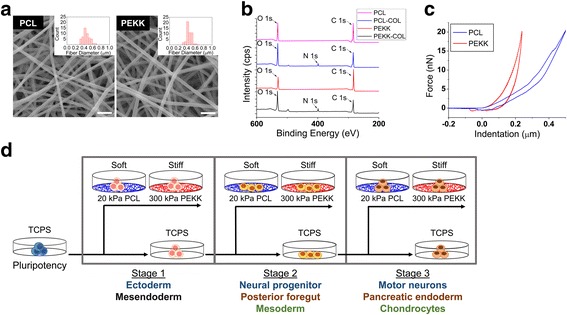

Electrospun scaffolds provide a means to examine the contributions of substrate stiffness on stem cell differentiation while uniquely regulating cell/colony morphologies [12, 13]. To synthesize mechanically distinctive, yet morphologically and surface chemically similar substrates, we optimized the electrospinning process of PCL or PEKK to achieve average fiber diameters of approximately 486 ± 128 nm for PCL and 476 ± 77 nm for PEKK (Fig. 1a). The surface area of PCL and PEKK scaffolds was determined to be 2.70 m2/g and 2.85 m2/g, respectively, by the BET method. Taking into account the similar density of PCL (1.145 g/cm3) and PEKK (1.278 g/cm3) and the similar fiber diameters, we estimate a similar porosity between the scaffolds. Collagen type I was chemically conjugated to these substrates via zero-length crosslinking by NHS/EDAC, and their surface modification was confirmed by XPS and immunofluorescent microscopy (Fig. 1b). The XPS spectra of collagen-conjugated electrospun PCL and PEKK nanofibers show the presence of nitrogen (N1s) at 400 eV, specific to the amino acids of collagen, in addition to the elemental peaks of the polymers of O1s and C1s at the binding energies of 530 and 284 eV, respectively. The 10-μm thick substrates were mechanically characterized by atomic force microscopy to calculate the reduced Young’s moduli of approximately 20 kPa for PCL and 300 kPa for PEKK from force-indentation curves (Fig. 1c). To examine the effects of temporally varied substrate stiffness on the differentiation efficiency of iPSCs at different developmental stages, the cells were cultured on either the soft (20 kPa) or stiff (300 kPa) substrates during differentiation towards motor neuron, pancreatic endoderm, or chondrocyte identities (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of electrospun substrates and experimental schematic to examine the effects of temporally varied substrate stiffness. a Scanning electron micrographs and fiber diameter histograms (insets) of electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) and polyether-ketone-ketone (PEKK) substrates (scale bar = 2 μm). b XPS spectra of electrospun PCL and PEKK substrates with/without collagen (COL) conjugation. c Representative force-indentation curves of electrospun PCL and PEKK substrates by atomic force microscopy. d A schematic of the experimental design to examine the effects of temporally varied substrate stiffness on each developmental stage of differentiation. Human iPSCs were differentiated along three phenotypes from each germ layer lineage via sequential supplementation of biochemicals (e.g., Stage 1: ectoderm; Stage 2: neural progenitor; Stage 3: motor neurons). Human iPSCs were cultured on tissue culture polystyrene plates (TCPS) prior to passaging for Stage 1 differentiation to either mesendoderm or ectoderm on soft (PCL) or stiff (PEKK) electrospun substrates. Alternatively, cells were continuously cultured on TCPS during Stage 1 differentiation before being seeded onto the soft or stiff electrospun substrates for further differentiation to Stage 2. Similar passaging and differentiation on either TCPS or the soft/stiff substrates were performed for Stage 3. At the end of each differentiation stage, the samples were analyzed for gene and protein expression of lineage/developmental stage-specific markers

Cells cultured on different substrates (i.e., soft PCL, stiff PEKK or TCPS control) at each differentiation stage were subjected to defined growth factors [14–16]. Briefly, motor neuron differentiation was induced by initial dual inhibition of SMAD signaling [17] followed by patterning to motor neurons using brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), ascorbic acid, sonic hedgehog (SHH), and retinoic acid [14]. Pancreatic endoderm differentiation was induced by high concentrations of activin A followed by primitive gut tube, posterior foregut, and pancreatic endoderm/endocrine precursor induction using fetal bovine serum (FBS), KAAD-cyclopamine, and retinoic acid [15]. Finally, chondrocyte differentiation was initiated by primitive streak induction with Wnt3a/activin A, followed by mesoderm induction using bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) and basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2), and chondrogenesis by decreasing BMP4 and increasing growth differentiation factor 5 (GDF5) concentrations [16]. Each of the biochemically driven protocols was optimized to yield the highest population of cells expressing lineage/developmental stage-specific markers to ultimately enhance the overall differentiation efficiency. However, such step-wise protocols typically do not examine how different substrate stiffness affects differentiation at each stage, and forego the opportunity to further enhance the differentiation efficiency via optimization of the physical cell niche.

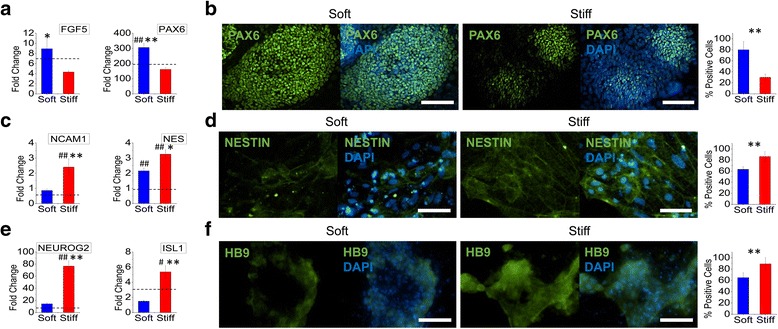

We first examined how electrospun substrate stiffness affected the differentiation of iPSCs to motor neurons (Fig. 2). During the first stage of differentiation towards ectodermal lineage from the pluripotent state, the expression of ectodermal markers FGF5 and PAX6 was significantly increased on the soft substrates (Fig. 2a). PAX6, at the protein level, also showed enhanced expression on the soft substrates with a 50% increase in percent-positive PAX6 cells as compared to those on the stiff substrates (Fig. 2b). To further examine the effects of substrate stiffness on the downstream differentiation, ectodermal cells were subcultured onto either soft or stiff substrates for subsequent neural progenitor differentiation. Unlike the previous differentiation stage, the differentiation efficiency of ectodermal cells to neural progenitors was enhanced on the stiff substrate (Fig. 2c and d). A significant increase in gene expression of NCAM1 and NES (Fig. 2c) and protein expression of NESTIN (Fig. 2d) was observed when cells were cultured on the stiff substrates. The final downstream specification of neural progenitors towards motor neurons was similarly enhanced on the stiff substrates as evident from significant increases of motor neuron markers NEUROG2 and ISL1 at the gene level and HB9 at the protein level on the stiff substrates (Fig. 2e and f). Unlike studies using hydrogel systems where neurogenesis is enhanced on softer substrates, our results indicate that specification of neural progenitor cells to motor neurons is enhanced on stiffer substrates [18, 19]. Inherent differences in topography and the pliability of electrospun fiber networks, in addition to the tested stiffness range and the specified differentiation stage, may collectively contribute to this discrepancy. Nevertheless, the results presented here demonstrate the mechanoresponsive nature of iPSCs at the early stages of lineage commitment where ectodermal induction is enhanced on soft substrates while the downstream specification to neural progenitors or motor neurons is enhanced on stiffer electrospun substrates.

Fig. 2.

The stage-specific effects of substrate stiffness on motor neuron differentiation. Human iPSCs were differentiated on either soft (PCL) or stiff (PEKK) electrospun substrates to (a, b) ectodermal, (c, d) neural progenitor, or (e, f) motor neuron lineage. a Gene expression of ectodermal markers FGF5 and PAX6 was significantly upregulated on soft substrates as compared to stiff substrates. b Immunofluorescent imaging and quantification of percent-positive cells showed that PAX6 protein expression was significantly higher on soft substrates after ectodermal induction (green: PAX6; blue: DAPI; scale bar = 100 μm). c Gene expression of neural progenitor markers NCAM1 and NES was significantly upregulated on stiff substrates as compared to soft substrates. d Immunofluorescent imaging and quantification of percent-positive cells showed that NESTIN protein expression was higher on stiff substrates (green: NESTIN; blue: DAPI; scale bar = 100 μm). e Gene expression of motor neuron markers NEUROG2 and ISL1 was significantly upregulated on stiff substrates as compared to soft substrates. f Immunofluorescent imaging and quantification of percent-positive cells showed that HB9 protein expression was higher on stiff substrates (green: HB9; blue: DAPI; scale bar = 100 μm). Gene expression was normalized to that of cells from the preceding stage of differentiation cultured on TCPS (fold change = 1). The dashed line represents the average fold change of differentiated cells on TCPS. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, versus TCPS differentiated controls. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, between substrates

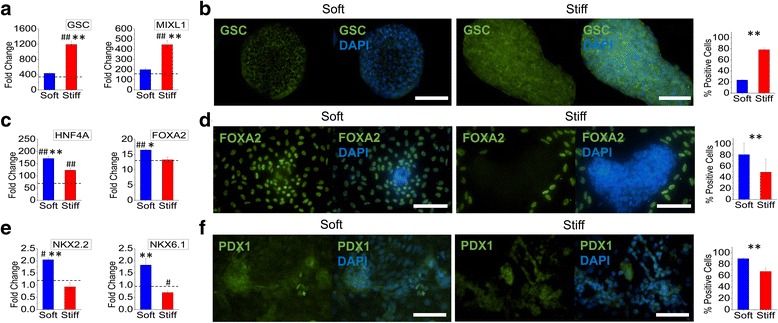

To examine the endodermal lineage differentiation of iPSCs, we alternatively directed the cells towards pancreatic endoderm specification. In contrast to early ectodermal differentiation, expression of mesendodermal markers GSC and MIXL1 was significantly increased on the stiff substrates as compared to both the soft substrates and TCPS controls when iPSCs were subjected to differentiation towards mesendodermal lineage (Fig. 3a). GSC expression at the protein level was also significantly enhanced on the stiff substrates (Fig. 3b). On the other hand, the subsequent differentiation of mesendodermal cells to posterior foregut was significantly enhanced on the soft substrates evident by the greater gene expression of HNF4A and FOXA2 (Fig. 3c). In accordance, protein expression of FOXA2 was significantly enhanced on the soft substrates showing 32% greater percent-positive cells as compared to those on the stiff substrates (Fig. 3d). The final specification of posterior foregut cells to pancreatic endoderm was also significantly enhanced on the soft substrates evident from the gene expression of pancreatic markers NKX2.2 and NKX6.1 and the protein expression of PDX1 (Fig. 3e and f).

Fig. 3.

The stage-specific effects of substrate stiffness on pancreatic endoderm differentiation. Human iPSCs were differentiated on either soft (PCL) or stiff (PEKK) electrospun substrates to (a, b) mesendodermal, (c, d) posterior foregut, or (e, f) pancreatic endoderm lineage. a Gene expression of mesendodermal markers GSC and MIXL1 was significantly upregulated on stiff substrates as compared to soft substrates. b Immunofluorescent imaging and quantification of percent-positive cells showed that GSC protein expression was significantly higher on stiff substrates (green: GSC; blue: DAPI; scale bar = 100 μm). c Gene expression of posterior foregut markers HNF4A and FOXA2 was significantly upregulated on soft substrates as compared to stiff substrates. d Immunofluorescent imaging and quantification of percent-positive cells showed that FOXA2 protein expression was significantly higher for cells cultured on soft substrates (green: FOXA2; blue: DAPI; scale bar = 100 μm). e Gene expression of pancreatic endoderm markers NKX2.2 and NKX6.1 was significantly upregulated on soft substrates as compared to stiff substrates. f Immunofluorescent imaging and quantification of percent-positive cells showed that PDX1 protein expression was higher on soft substrates (green: PDX1; blue: DAPI; scale bar =100 μm). The dashed line represents the average fold change of differentiated cells on TCPS. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, versus TCPS differentiated controls. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, between substrates

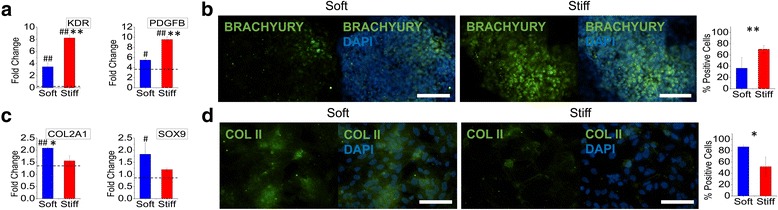

In spite of the same origin with posterior foregut, the differentiation of mesendodermal cells to mesodermal specification was preferred on the stiff substrates (Fig. 4a and b). Gene expression of mesodermal markers KDR and PDGFB was significantly enhanced on the stiff substrates as compared to both the soft substrates and TCPS control (Fig. 4a). Additionally, protein expression of BRACHYURY was also enhanced with a significant increase of 33% positive cells on the stiff substrates as compared to the soft substrates (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that the mechanical microenvironment contributes to the divergence of a mesendoderm population where specification of endodermal phenotypes is enhanced on soft substrates whereas mesodermal phenotypes are enhanced on stiff substrates. Similarly, the specification of mesodermal cells to chondrocytes was significantly enhanced on the soft substrates (Fig. 4c and d). Gene expression of COL2A1 and SOX9 was significantly increased on the soft substrates, with protein expression of collagen type II also displaying a similar trend (Fig. 4c and d). Taken together, these results suggest that the final stage of downstream differentiation to either pancreatic endoderm or chondrocyte shares the same substrate stiffness-dependent differentiation behaviors although a divergence in optimal substrate stiffness was observed for the preceding differentiation stage. Chondrocyte commitment from a mesodermal stage is consistent with our previous work with mesenchymal stem cells where chondrogenesis was enhanced on a soft electrospun substrate [13].

Fig. 4.

The stage-specific effects of substrate stiffness on chondrocyte differentiation. Human iPSCs were differentiated on either soft (PCL) or stiff (PEKK) electrospun substrates to (a, b) mesoderm or (c, d) chondrocyte lineage. a Gene expression of mesoderm markers KDR and PDGFB was significantly upregulated on stiff substrates as compared to soft substrates. b Immunofluorescent imaging and quantification of percent-positive cells showed that BRACHYURY protein expression was significantly higher on stiff substrates (green: BRACHYURY; blue: DAPI; scale bar = 100 μm). c Gene expression of chondrocyte markers COL2A1 and SOX9 was upregulated on soft substrates as compared to stiff substrates. d Immunofluorescent imaging and quantification of percent-positive cells showed that collagen type II protein expression was significantly higher on soft substrates (green: COL II; blue: DAPI; scale bar = 100 μm). The dashed line represents the average fold change of differentiated cells on TCPS. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, versus TCPS differentiated controls. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, between substrates

Conclusions

Overall, the results presented in this proof-of-concept study are the first to systematically demonstrate the significant role of the temporally varied mechanical microenvironment on the differentiation of stem cells in a lineage- and developmental stage-specific manner. For example, neural induction is initially enhanced on soft substrates but, as the differentiation process progresses, stiff substrates promote neural progenitor and motor neuron specification. In contrast, mesendodermal differentiation is significantly enhanced on stiff substrates but further specification to posterior foregut requires a soft substrate, indicating that dynamic changes of substrate stiffness may further enhance differentiation efficiency. Although optimization of the differentiation protocol was beyond the scope of this study, the optimal combination of the substrate stiffness examined in this study (e.g., sequential application of soft-stiff-stiff substrates for each stage of ectodermal-neural progenitor-motor neuron differentiation) is estimated to achieve an approximately 5-, 8-, and 11-fold increase in the yield of differentiated cells in neural, pancreatic endoderm, and chondrocytic phenotypes, respectively. Collectively, these results suggest that optimization of the mechanical microenvironment using electrospun nanofibrous substrates, incorporated into biochemically driven differentiation protocols, provides an efficient method of producing therapeutic cells for translational applications of iPSCs.

Additional files

Chemical characterization of electrospun scaffolds. Fluorescence images of nanofibrous scaffolds that are collagen type I-conjugated or unconjugated and stained with an anticollagen type I antibody. (PDF 186 kb)

Supporting information on Materials and methods. Detailed materials and methods for the differentiation of iPSCs towards various lineages, gene/protein expression analysis, statistical analysis, and a table of RT-PCR primers. (PDF 395 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the UCR Stem Cell Core Facility. The UCR Stem Cell Core is a CIRM funded shared facility.

Funding

This study was funded by the UCR Initial Complement Fund and the National Science Foundation (NSF) GRFP grant award number DGE-1326120.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AFM

Atomic force microscopy

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BET

Brunauer-Emmett-Teller

- BMP4

Bone morphogenetic protein 4

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- FGF2

Fibroblast growth factor

- GDF5

Growth differentiation factor 5

- HFP

1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol

- iPSC

Induced pluripotent stem cell

- PCL

Poly(ε-caprolactone)

- PEKK

Polyether-ketone-ketone

- SHH

Sonic hedgehog

- TCPS

Tissue culture polystyrene plates

- XPS

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

Author’s contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. MM, RJL, GI, AO, and DM performed experiments and analyzed data for figures. MM prepared the figures. MM, H-PS, and JN wrote the main manuscript text.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13287-017-0667-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Maricela Maldonado, Email: mmald006@ucr.edu.

Rebeccah J. Luu, Email: rluu004@ucr.edu

Gerardo Ico, Email: gico001@ucr.edu.

Alex Ospina, Email: aospina@engr.ucr.edu.

Danielle Myung, Email: dmyung@engr.ucr.edu.

Hung Ping Shih, Email: hshih@coh.org.

Jin Nam, Phone: 951-827-2064, Email: jnam@engr.ucr.edu.

References

- 1.Aoi T. 10th anniversary of iPS cells: the challenges that lie ahead. J Biochem. 2016;160(3):121–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Ader M, Tanaka EM. Modeling human development in 3D culture. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;31:23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ranga A, Gjorevski N, Lutolf MP. Drug discovery through stem cell-based organoid models. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;69–70:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clevers H. Modeling development and disease with organoids. Cell. 2016;165(7):1586–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pera MF, et al. What if stem cells turn into embryos in a dish? Nat Methods. 2015;12(10):917–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Leary T, et al. Tracking the progression of the human inner cell mass during embryonic stem cell derivation. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(3):278. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murry CE, Keller G. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to clinically relevant populations: lessons from embryonic development. Cell. 2008;132(4):661–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pera MF, Trounson AO. Human embryonic stem cells: prospects for development. Development. 2004;131(22):5515–25. doi: 10.1242/dev.01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kattman SJ, et al. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(2):228–40. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao J, Greber B. Concise review: signaling control of early fate decisions around the human pluripotent stem cell state. Stem Cells. 2016;35:277–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Maldonado M, et al. The effects of electrospun substrate-mediated cell colony morphology on the self-renewal of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Biomaterials. 2015;50:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maldonado M, et al. Enhanced lineage-specific differentiation efficiency of human induced pluripotent stem cells by engineering colony dimensionality using electrospun scaffolds. Adv Healthc Mater. 2016;5(12):1408–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Nam J, et al. Modulation of embryonic mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation via control over pure mechanical modulus in electrospun nanofibers. Acta Biomater. 2011;7(4):1516–24. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers SM, et al. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(3):275–80. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroon E, et al. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(4):443–52. doi: 10.1038/nbt1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oldershaw RA, et al. Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells toward chondrocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(11):1187–94. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itoh F, Watabe T, Miyazono K. Roles of TGF-beta family signals in the fate determination of pluripotent stem cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;32:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, et al. Neural differentiation from pluripotent stem cells: the role of natural and synthetic extracellular matrix. World J Stem Cells. 2014;6(1):11–23. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v6.i1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banerjee A, et al. The influence of hydrogel modulus on the proliferation and differentiation of encapsulated neural stem cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30(27):4695–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Chemical characterization of electrospun scaffolds. Fluorescence images of nanofibrous scaffolds that are collagen type I-conjugated or unconjugated and stained with an anticollagen type I antibody. (PDF 186 kb)

Supporting information on Materials and methods. Detailed materials and methods for the differentiation of iPSCs towards various lineages, gene/protein expression analysis, statistical analysis, and a table of RT-PCR primers. (PDF 395 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.