Abstract

Objective

This study was to aggregate the prevalence and risks of epiretinal membranes (ERMs) and determine the possible causes of the varied estimates.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

The search strategy was designed prospectively. We searched PubMed, Embase and Web of Science databases from inception to July 2016. Reference lists of the included literatures were reviewed as well.

Study selection

Surveys published in English language from any population were included if they had a population-based design and reported the prevalence of ERM from retinal photography with or without optical coherence tomography. Eligibility and quality evaluation was conducted independently by two investigators.

Data extraction

The literature search generated 2144 records, and 13 population-based studies comprising 49 697 subjects were finally included. The prevalence of ERM and the ORs of potential risk factors (age, sex, myopia, hypertension and so on) were extracted.

Results

The pooled age-standardised prevalence estimates of earlier ERM (cellophane macular reflex (CMR)), advanced ERM (preretinal macular fibrosis (PMF)) and any ERM were 6.5% (95% CI 4.2% to 8.9%), 2.6% (95% CI 1.8% to 3.4%) and 9.1% (95% CI 6.0% to 12.2%), respectively. In the subgroup analysis, race and photography modality contributed to the variation in the prevalence estimates of PMF, while the WHO regions and image reading methods were associated with the varied prevalence of CMR and any ERM. Meta-analysis showed that only greater age and female significantly conferred a higher risk of ERMs.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that ERMs are relatively common among aged population. Race, image taking and reading methodology may play important roles in influencing the large variability of ERM prevalence estimates.

Keywords: epiretinal membranes, prevalence, risk factors, meta-analysis, population-based

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that pools the age-standardised prevalence of epiretinal membrane (ERM) from population-based studies.

The investigators strictly adhered to the guidelines for systematic review and meta-analysis. All included surveys were of desirable quality and large scale.

We aggregated the prevalence of ERM and its subtype estimates (cellophane macular reflex and preretinal macular fibrosis).

Lack of studies from the African and European continents makes it difficult to project ERM prevalence estimates worldwide.

We are unable to aggregate the data on the relationship between ERM prevalence and visual acuity impairment due to lack of studies on their association.

We only included literatures in English for the present analysis.

Introduction

Epiretinal membranes (ERMs) are common retinal conditions that can impair visual acuity in old persons. ERMs may occur without any antecedent ocular conditions or surgical procedures, termed idiopathic or primary ERM. Those associated with other eye diseases (eg, retinal vascular occlusion and diabetic retinopathy), trauma or surgery are referred to as secondary ERM. Under ophthalmoscopy, earlier stage ERMs present as increases of the light reflex from the retina inner surface, which is called cellophane macular reflex (CMR). As the membrane progresses, it can contract and create superficial retinal folds. Massive folds make the retina appear with grey linear reflexes, which are termed preretinal macular fibrosis (PMF). For most cases at the advanced stage, fibrotic membranes generate tangential traction on the macula, causing macular oedema, metamorphopsias and central vision impairment.1

After the landmark study Beaver Dam Eye Study (BDES) reported the prevalence of ERM in 1994,2 several large-scale population-based studies investigated the epidemics of ERMs in Singapore,3 4 Japan,5 Australia6 7 and China.8 9 Most of these surveys introduced retinal photography and the same classification scheme for ERMs as that in BDES. However, considerable variation in ERM epidemiology across races and regions has been noted. For example, in the population-based Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA),10 ERM was as prevalent as 39.0% in Chinese, 27.5% in Caucasian, 26.2% in Africans and 29.3% in Hispanics. These estimates were much higher than those in the Handan Eye Study in North China (3.4%),8 the Blue Mountains Eye Study in Australia (7%)7 and the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study in the USA (19.9%).11 Reasons for such variability may be complex, but it has been considered to be associated with the differences in study design, population characteristics, as well as the definition of cases. Moreover, some studies did not compute the age-standardised estimates of prevalence, making direct comparison between studies difficult.

Estimating the prevalence and risk of ERM is perhaps the first step to better clinical management and understanding the burden of this disease. Therefore, we conducted the present analysis to synthesise data from population-based studies to estimate the prevalence of ERMs and to identify underlying factors causing prevalence variability as well as major risk factors for ERMs.

Methods

In this study, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (the PRISMA statement,12 see online supplementary information).

bmjopen-2016-014644supp001.pdf (64.1KB, pdf)

Search strategy and selection criteria

The search strategy was designed prospectively. We searched all reports on population-based studies for the prevalence of ERMs using PubMed, Embase and Web of Science from inception to July 2016. All English language articles were retrieved using prespecified search terms. The search terms and strategies were showed in detail in supplementary information. The reference lists of all included articles were reviewed, and the full texts of potentially related papers were examined.

We designed a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria for literature screening. Studies included were those population-based surveys in which ERMs were diagnosed on the basis of retinal colour photography with or without a combination of optical coherence tomography (OCT). Studies without population-based (eg, hospital-based or specific population-based) design were excluded. Eligibility evaluation was conducted independently by two investigators (WX and XC) using predesigned forms. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Quality assessment and data extraction

There were no consensus guidelines on evaluating cross-sectional surveys, so we adopted the quality assessment criteria used by de Weerd et al 13 and Rogers et al.14 The criteria covered the following four aspects (online supplementary information): (1) representing the general population. To achieve this, studies should be undertaken using population registries, inhabitants of a specific area or people registered with a general practice. (2) Appropriately recruiting the population. Recruitment was considered appropriate if it was performed randomly or consecutively rather than for convenience or from volunteers. (3) Adequate response rate (>70%). (4) Objective documentation of the outcomes, which means documentation of ERMs by retinal photography according to standardised protocols and graded according to standard definitions. Fulfilment of three or four points was considered adequate quality. Quality of all included studies was assessed independently by two investigators (WX and XC) using quality assessment forms based on the aforementioned criteria.

For included studies, data were extracted independently by two reviewers (WX and XC) on to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (XP professional edition; Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. We extracted the following data from each study: country, year, sample size, age range, race/ethnicity, examination methods, image grading approach, crude prevalence with95% CI and ORs with 95% CI for risk factors (including age, gender, refractive error, hypertension, diabetes, smoking status, alcohol intake, early age-related macular degeneration (AMD), body mass index (BMI) and hyperlipidaemia). Our key outcomes of interest were the prevalence and risk factors of ERM.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Age-standardised prevalence of ERMs in each study was calculated by projecting its crude prevalence rates to the WHO world standard age structure.15 This method has been adopted to estimate the regional and global prevalence and burden of several major eye diseases, such as AMD,16 diabetic retinopathy17 and retinal vein occlusion.14 The I2 statistic was used to estimate heterogeneity between studies with a value greater than 50% as significantly heterogeneous. Due to the marked difference between studies, pooled prevalence was synthesised using random-effect models.18 Sources of heterogeneity were explored by conducting subgroup analysis accordingly to race/ethnicity, WHO regions, testing method (photography with or without OCT), photography technique (digital or film) and image grading approach (centralised grading centre vs independently trained graders). To aggregate ORs for potential risk factors, random-effect models were used if included studies were significantly heterogeneous (I2 > 50%); otherwise, fixed-effect models were used. All statistical analysis was performed with STATA software (V.13.0).

Results

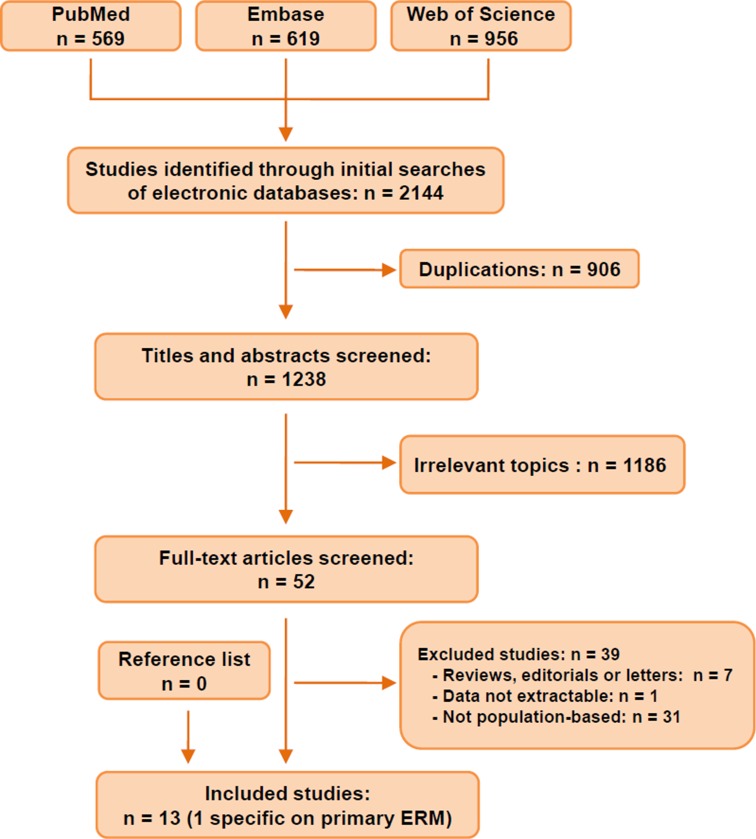

Figure 1 exhibits the procedure of literature searching and screening. The systematic searches yielded 2144 records. After removing 906 duplications, 1238 studies were screened through titles and abstracts. Among them, we ruled out 1186 irrelevant articles and reviewed the left 52 studies in full text. Finally, we identified 13 studies2 3 5–11 19–21 that were eligible for inclusion (table 1). Across the 13 studies, sample sizes ranged from 15435 to 65658, including 49 697 individuals at risk of ERMs. Two studies (Funagata and Hisayama) scored three points in the quality assessment owing to their relatively low response rate (<70%), while the others all scored four points (see online supplementary information). The Beixinjing Study21 reported specifically on the prevalence of primary (idiopathic) ERM, whereas the other 12 studies documented the prevalence of any ERM (ie, both primary and secondary ERM). Geographically, the WHO regions of Western Pacific Region and the Americas were heavily represented, with all 13 studies done in these two regions. In other words, no studies had been done in the European, Africa, Southeast Asian or Eastern Mediterranean regions. Of these 13 studies, 12 studies (all except Funagata5) assessed ERMs using both eyes of each participant; nine studies performed photography after pharmacological mydriasis. The methods of photography varied between studies, with four studies using stereophotographing (vs nine using non-stereo photographing), four studies using 30° camera (vs nine using 45° camera) and six using film photography (vs seven using digital photography). Retinal images were graded at the reading centres at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (three studies), at the University of Sydney (seven studies) or by independent ophthalmologists/trained graders (four studies). Characteristics of the included studies were summarised in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of studies identified, included and excluded. ERM, epiretinal membrane.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Country | Year | N (% male) | Age range | Race/ethnicity | Eye examined | Pupil dilation | Fundus photography | Image grading | OCT used |

| BDES | USA | 1987–1988 | 4802 | 43–84 | Caucasian | Both | Yes | 30°; stereo; >3 fields; film | Reading centre at University of Wisconsin | No |

| Beixinjing* | China | 2010–2011 | 3326 (44.5) | 50–98 | Asian | Both | Yes | 45°; non-stereo; two fields; digital | Ophthalmologists | No |

| BMES | Australia | 1992–1993 | 3490 (43.8) | ≥49 | Caucasian | Both | Yes | 30°; stereo; six fields; film | Reading centre at University of Sydney | No |

| Funagata | Japan | 2000–2002 | 1543 (43.4) | ≥35 | Asian | Right eye | No | 45°; non-stereo; one field; film | Reading centre at University of Sydney | No |

| HES | China | 2006–2007 | 6565 (46.7) | ≥30 | Asian | Both | Part of* | 45°; non-stereo; two fields; digital | Ophthalmologists | Yes |

| Hisayama | Japan | 1998 | 1765 (38.5) | ≥40 | Asian | Both | Yes | 45°; non-stereo; one field; film | Ophthalmologists | No |

| Jiangning | China | 2012–2013 | 2005 (43.7) | ≥50 | Asian | Both | No | 45°; non-stereo; >2 fields; digital | Trained graders | Yes |

| LALES | USA | 2000–2003 | 5982 (42.0) | ≥40 | Hispanic | Both | Yes | 30°degree; stereo, three fields; film | Reading centre at University of Wisconsin | No |

| MESA | USA | 2002–2004 | 5960 (47.9) | 45–84 | White, black; Asian; Hispanic | Both | No | 45°; non-stereo; two fields; digital | Reading centre at University of Wisconsin | No |

| SCES | Singapore | 2009–2011 | 3353 | 40–80 | Asian | Both | Yes | 45°; non-stereo; two fields; digital | Reading centre at University of Sydney | No |

| SiMES | Singapore | 2004–2006 | 3265 (48.1) | 40–80 | Asian | Both | Yes | 45°; non-stereo; two fields; digital | Reading centre at University of Sydney | No |

| SINDI | Singapore | 2007–2009 | 3328 (50.2) | 40–80 | Asian | Both | Yes | Non-stereo; two fields; digital | Reading centre at University of Sydney | No |

| VIP | Australia | 1992–1997 | 4313 (47.0) | ≥40 | Caucasian | Both | Yes | 30°; stereo; two fields; film | Reading centre at University of Sydney | No |

*Data only available for primary ERMs.

BDES, Beaver Dam Eye Study; BMES, Blue Mountains Eye Study; HES, Handan Eye Study; LALES, Los Angeles Latino Eye Study; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; OCT, optical coherence tomography; SCES, Singapore Chinese Eye Study; SiMES, Singapore Malay Eye Study; SINDI, Singapore Indian Eye study; VIP, Visual Impairment Project.

Analyses of the 12 studies concerning any ERM (except the Beixinjing Study exclusively on primary ERM) showed that the overall age-standardised prevalence of CMR was 6.5% (95% CI 4.2% to 8.9%), PMF was 2.6% (95% CI 1.8% to 3.4%) and any ERM was 9.1% (95% CI 6.0% to 12.2%) (table 2). Specific to primary ERM, the pooled prevalence of CMR, PMF and all primary ERM were 7.1% (95% CI 3.3% to 10.8%), 2.0% (95% CI 1.3% to 2.8%) and 9.2% (95% CI 4.7% to 13.8%), respectively. Six studies reported the prevalence of secondary ERM, and all explicitly defined the population at-risk as those with other ocular conditions (eg, retinal vascular disease and retinal detachment) or cataract surgery. The aggregated data showed the prevalence of secondary CMR, PMF and any ERM were 11.4% (95% CI 4.4% to 18.5%), 5.1% (95% CI 3.5% to 6.6%) and 16.6% (95% CI 9.7% to 23.6%), respectively.

Table 2.

Age-standardised prevalence of ERM by study

| Study | Year | N at-risk | Crude prevalence (%) | Age-standardised prevalence (%, 95% CI) | ||||

| CMR | PMF | Any ERM* | CMR | PMF | Any ERM* | |||

| All ERM† | ||||||||

| BDES | 1987–1988 | 4802 | – | – | – | 4.8 (4.3 to 5.4) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.0) | 6.4 (5.8 to 7.1) |

| BMES | 1992–1993 | 3490 | 4.8 | 2.7 | 7.0 | 3.8 (3.2 to 4.4) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.1) | 5.5 (4.8 to 6.2) |

| Funagata | 2000–2002 | 1543 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 5.4 | 2.7 (1.9 to 3.4) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.5) | 3.7 (2.8 to 4.6) |

| HES | 2006–2007 | 6565 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 3.4 | 2.3 (1.8 to 2.8) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.7) | 3.5 (2.9 to 4.0) |

| Hisayama | 1998 | 1765 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 4.0 | 2.2 (1.6 to 2.9) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.8) | 2.8 (2.1 to 3.5) |

| Jiangning | 2012–2013 | 2005 | 5.0 | 3.4 | 8.4 | 4.5 (3.7 to 5.4) | 3.1 (2.4 to 3.9) | 7.6 (6.5 to 8.7) |

| LALES | 2000–2003 | 5982 | 16.3 | 2.2 | 18.5 | 16.6 (15.7 to 17.6) | 2.5 (2.0 to 2.9) | 19.0 (18.0 to 20.0) |

| MESA | 2002–2004 | 5960 | 25.1 | 3.8 | 28.9 | 21.5 (20.1 to 22.5) | 3.0 (2.6 to 3.4) | 24.5 (23.4 to 25.6) |

| SiMES | 2004–2006 | 3265 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 11.8 | 4.7 (4.0 to 5.3) | 4.6 (4.0 to 5.3) | 9.3 (8.3 to 10.2) |

| SCES | 2009–2011 | 3353 | – | – | – | 7.0 (6.1 to 7.9) | 7.5 (6.6 to 8.3) | 13.0 (11.9 to 14.2) |

| SINDI | 2007–2009 | 3328 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 10.2 | 4.7 (4.0 to 5.3) | 4.1 (3.4 to 4.7) | 8.8 (7.9 to 9.7) |

| VIP | 1992–1997 | 4313 | 4.8 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 3.8 (3.3 to 4.4) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) | 4.9 (4.4 to 5.5) |

| Pooled estimates | NA | 46 371 | – | – | – | 6.5 (4.2 to 8.9) | 2.6 (1.8 to 3.4) | 9.1 (6.0 to 12.2) |

| I2 | 99.3 | 98.2 | 99.5 | |||||

| Primary ERM | ||||||||

| BDES | 1987–1988 | 4125 | – | – | – | 4.5 (3.9 to 5.1) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6) | 5.8 (5.1 to 6.5) |

| Beixinjing | 2010–2011 | 3326 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.9) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.3) |

| HES | 2006–2007 | 6196 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.6) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.6) | 3.1 (2.6 to 3.7) |

| Jiangning | 2012–2013 | 1854 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 7.7 | 4.3 (3.4 to 5.2) | 3.0 (2.2 to 3.7) | 7.3 (6.1 to 8.4) |

| LALES | 2000–2003 | 5631 | 15.6 | 1.9 | 17.5 | 16.1 (15.2 to 17.1) | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.6) | 18.4 (17.3 to 19.4) |

| MESA | 2002–2004 | 4761 | 22.7 | 3.3 | 26.1 | 20.2 (19.1 to 21.3) | 2.7 (2.3 to 3.1) | 23.0 (21.7 to 24.1) |

| SiMES | 2004–2006 | 2734 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 9.5 | 4.5 (3.7 to 5.2) | 3.8 (3.2 to 4.5) | 8.3 (7.3 to 9.3) |

| SINDI | 2007–2009 | 2324 | 3.8 | 2.7 | 6.5 | 4.3 (3.4 to 5.2) | 2.8 (2.1 to 3.5) | 7.0 (5.9 to 8.2) |

| Pooled estimates | NA | 30 951 | – | – | – | 7.1 (3.3 to 10.8) | 2.0 (1.3 to 2.8) | 9.2 (4.7 to 13.8) |

| I2 | 99.6 | 97.9 | 99.7 | |||||

| Secondary ERM | ||||||||

| HES | 2006–2007 | 269 | 7.1 | 3.7 | 12.3 | 6.7 (1.9 to 11.5) | 3.7 (0 to 7.8) | 11.1 (5.0 to 17.3) |

| Jiangning | 2012–2013 | 151 | 10.6 | 6.6 | 17.2 | 7.0 (3.4 to 10.7) | 3.9 (1.2 to 6.6) | 10.9 (6.6 to 15.2) |

| LALES | 2000–2003 | 345 | 27.0 | 7.5 | 34.5 | 19.8 (14.4 to 25.2) | 6.1 (2.9 to 9.3) | 25.9 (20.0 to 31.9) |

| MESA | 2002–2004 | 1199 | 34.3 | 5.8 | 40.1 | 25.1 (22.2 to 28.1) | 3.4 (2.5 to 4.4) | 28.6 (25.6 to 31.6) |

| SiMES | 2004–2006 | 531 | 9.8 | 13.6 | 23.4 | 5.3 (2.5 to 8.1) | 7.1 (5.2 to 9.0) | 12.4 (9.1 to 15.7) |

| SINDI | 2007–2009 | 1004 | 9.1 | 9.8 | 18.8 | 5.1 (3.6 to 6.5) | 6.0 (4.2 to 7.8) | 11.0 (8.8 to 13.3) |

| Pooled estimates | NA | 3499 | – | – | – | 11.4 (4.4 to 18.5) | 5.1 (3.5 to 6.6) | 16.6 (9.7 to 23.6) |

| I2 | 97.0 | 69.4 | 95.4 | |||||

*Any ERM: both CMR and PMF.

†All ERM: both primary and secondary ERM.

BDES, Beaver Dam Eye Study; BMES, Blue Mountains Eye Study; CMR, cellophane macular reflex; ERM, epiretinal membrane; HES, the Handan Eye Study; LALES, Los Angeles Latino Eye Study; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; PMF, preretinal macular fibrosis; SCES, Singapore Chinese Eye Study; SiMES, Singapore Malay Eye Study; SINDI, Singapore Indian Eye study; VIP, Visual Impairment Project.

The age-standardised prevalence of ERMs by subgroups of interest was shown in table 3. The aggregated prevalence of any ERM varied according to the WHO regions, different image acquisition and grading method. Three studies from the Americas, in which retinal images were also graded by the reading centre at the University of Wisconsin-Madison,2 10 11 documented a much higher prevalence (14.4%) than those from Western Pacific region (8.5%). Of note, this trend was potentially attributed to the extremely high prevalence of CMR in the Americas (14.3% vs 4.0% in Western Pacific region). For PMF, the advanced stage of ERM, studies using film photography synthesised a much lower prevalence than that using digital photography (1.5% vs 3.1%). PMF was slightly more prevalent in Asians than in Caucasians (3.6% vs 2.5%). There were only two studies from China that introduced OCT to confirm ERM cases.8 9 Intriguingly, studies with a combination of OCT demonstrated lower prevalence in both CMR (3.4% vs 7.2% without OCT) and PMF (1.8% vs 2.8% without OCT).

Table 3.

Age-standardised prevalence of ERMs by subgroups of interest

| CMR | PMF | Any ERM | References | |||||||

| Studies (n) |

Prevalence (%, 95% CI) |

I2 (%) | Studies (n) |

Prevalence (%, 95% CI) |

I2 (%) | Studies (n) |

Prevalence (%, 95% CI) |

I2 (%) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Caucasian | 4 | 8.9 (4.6 to 13.2) | 99.4 | 4 | 2.0 (1.4 to 2.7) | 88.8 | 4 | 11.0 (5.9 to 16.1) | 99.5 | 2 6 7 10 |

| Asian | 8 | 6.5 (4.6 to 8.5) | 98.2 | 8 | 3.6 (2.2 to 4.9) | 98.7 | 8 | 10.5 (7.2 to 13.8) | 99.1 | 3–5 8–10 19 20 |

| WHO regions | ||||||||||

| The Americas | 3 | 14.3 (3.6 to 25.0) | 99.8 | 3 | 2.4 (1.6 to 3.2) | 91.6 | 3 | 14.4 (5.6 to 23.2) | 99.7 | 2 10 11 |

| Western Pacific | 9 | 4.0 (3.1 to 4.9) | 94.2 | 9 | 2.7 (1.7 to 3.7) | 98.3 | 9 | 8.5 (4.7 to 8.4) | 98.2 | 3–9 19 20 |

| Testing method | ||||||||||

| Photography only | 10 | 7.2 (4.2 to 10.1) | 99.5 | 10 | 2.8 (1.9 to 3.7) | 97.8 | 10 | 9.1 (6.0 to 12.2) | 99.3 | 2–11 19 20 |

| Photography+OCT | 2 | 3.4 (1.2 to 5.5) | 94.8 | 2 | 1.8 (0 to 3.7) | 97.6 | 2 | 5.5 (1.5 to 9.5) | 97.7 | 8 9 |

| Photography | ||||||||||

| Film | 6 | 5.6 (2.5 to 8.8) | 99.3 | 6 | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.0) | 92.2 | 6 | 7.0 (3.4 to 10.7) | 99.4 | 2 5–7 11 20 |

| Digital | 6 | 7.4 (3.2 to 11.7) | 99.5 | 6 | 3.8 (1.9 to 5.7) | 99.0 | 6 | 10.0 (5.7 to 14.3) | 99.3 | 3 4 8–10 19 |

| Image graded by | ||||||||||

| RC at UW–Madison* | 3 | 14.3 (3.6 to 25.0) | 99.8 | 3 | 2.4 (1.6 to 3.2) | 91.6 | 3 | 14.4 (5.6 to 23.2) | 99.7 | 2 10 11 |

| RC at USYD† | 6 | 4.4 (3.5 to 5.4) | 92.3 | 6 | 3.4 (1.9 to 4.9) | 98.1 | 6 | 7.5 (5.1 to 9.9) | 98.1 | 3–7 19 |

| Ophthalmologists or trained raters | 3 | 3.0 (1.7 to 4.2) | 90.9 | 3 | 2.6 (1.8 to 3.4) | 98.1 | 3 | 4.6 (2.3 to 6.8) | 96.4 | 8 9 20 |

*Reading centre at University of Wisconsin-Madison.

†Reading centre at University of Sydney.

CMR, cellophane macular reflex; ERM, epiretinal membrane; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PMF, preretinal macular fibrosis.

As expected, individuals with greater age were more likely to have any ERM (OR=1.19 per year increase, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.26). Compared with males, females carried higher risk of ERM (OR=1.34, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.53). Smokers had an unexpected lower risk of ERM compared with non-smokers (OR=0.67, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.78). Other factors analysed, including myopia, hyperopia, hypertension, diabetes, alcohol intake, early AMD, BMI and hyperlipidaemia, were not associated with the risk of any ERM (table 4).

Table 4.

Pooled ORs for risk of any epiretinal membrane

| Risk factors | Studies | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | References |

| Age (per year) | 5 | 1.19 (1.13 to 1.26) | 95.1 | 3–5 9 10 19 |

| Sex (female) | 6 | 1.34 (1.17 to 1.53) | 24.8 | 3–5 9 19 20 |

| Myopia (present) | 4 | 1.21 (0.67 to 2.19) | 88.9 | 6 8 9 19 |

| Hyperopia (present) | 3 | 1.23 (0.78 to 1.94) | 83.8 | 6 8 19 |

| Hypertension (present) | 6 | 1.04 (0.90 to 1.20) | 11.2 | 4–6 9 19 20 |

| Diabetes (present) | 6 | 1.13 (0.92 to 1.38) | 17.1 | 4–6 9 19 20 |

| Smoking (present) | 7 | 0.67 (0.58 to 0.78) | 0 | 3–6 8 19 20 |

| Alcohol intake (present) | 3 | 0.97 (0.75 to 1.25) | 0 | 6 9 20 |

| Early AMD (present) | 3 | 0.96 (0.63 to 1.47) | 60.7 | 2 5 6 |

| BMI (per kg/m2) | 5 | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.01) | 0 | 4–6 9 20 |

| Hyperlipidaemia (present) | 4 | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11) | 62.0 | 4 5 9 20 |

AMD, age-related macular degeneration; BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

This study provides estimates for the prevalence of ERMs and its two stages using data from most appropriate population-based studies in the literature. Using data from 13 studies with 49 697 participants, we estimated the age-standardised prevalence of any ERM (both primary and secondary) to be as high as 9.1%, with CMR and PMF as 6.5% and 2.6%, respectively. Race, retinal image taking and grading method were responsible for the variation of the prevalence estimates across studies. Among the factors analysed, greater age and female sex were significantly associated with higher risk of developing ERMs.

The prevalence of ERM has been documented over the last 30 years in several population-based surveys. However, these estimates have varied considerably across studies. For example, the prevalence of any ERM has been estimated to be 35.7% in Latinos aged 70–79 years11, which was fivefold more prevalent than that in the same age Japanese (6.8%).20 To form an age-standardised estimate of ERM prevalence, and further to explore possible sources of heterogeneity, we conducted this study to synthesise the best available data. In this review, we identified 13 eligible studies with favourable quality, but they were predominantly carried out in Pacific Rim countries (the USA, Australia, Japan, Singapore and China). Further study is warranted in European and African regions so that we can generate the global prevalence and magnitude of this disease.

Previously, ERM susceptibility has been reported to vary between ethnic groups. MESA10 was the only study that directly compared the racial and ethnic differences of ERM prevalence within the same cohort. It reported a significantly higher prevalence rate for Chinese ethnicity (39.0%), followed by Hispanic (29.3%), Caucasian (27.5%) and African (26.2%) ethnicity. However, the sample sizes of each ethnic group were relatively small, particularly in the Chinese subgroup (n=724). However, our aggregated data of large sample size showed that ethnicity was less likely to be associated with ERM prevalence disparities. The prevalence difference between Asians and Caucasians for CMR and any ERM was negligible, indicating that race/ethnicity may have a limited role in ERM prevalence.

Our review shows that the variations in ERM prevalence between studies may be partly attributed to their methodological characteristics. In terms of image grading protocol, although all included studies consistently adopted the same classification scheme as that in the BDES,2 retinal images were graded in different fashions: three studies were read by the grading centre of the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the USA, six at the grading centre at the University of Sydney and the others graded by ophthalmologists or independently trained graders. In our subgroup analysis, three studies graded at the reading centre at University of Wisconsin-Madison pooled an extremely high prevalence of CMR and any ERM (14.3% and 14.4%, respectively). Due to all three studies from the Americas, differences in image reading patterns directly led to the regional differences in CMR and any ERM prevalence estimates. Taken account of the minimal difference in the synthesised PMF prevalence across reading centres, we could speculate that the substantial differences in estimated overall ERM prevalence originated from the systematic differences in grading CMR from retinal images. Accordingly, there is insufficient evidence to conclude whether the regional difference in ERM prevalence is attributable to the difference in geographical location per se or to the grading methodology. To address this issue, universal criteria for grading CMR and differentiation from normal fundus manifestations may need to be further standardised.

Interestingly, unlike CMR and any ERM, the pooled prevalence of PMF across regions were quite similar, but this prevalence was more likely to be affected by race and photography modality (film vs digital). Asians had a slightly higher prevalence of PMF (3.6% vs 2.0% in Caucasians), and digital photography seemed to detect more PMF cases than film photography (3.8% vs 1.5%).

OCT has been applied as the ‘gold standard’ in diagnosing vitreoretinal interface diseases in recent epidemiological studies.22–24 In clinical practice, OCT was superior to retinal photography in screening epiretinal irregularities25 and detecting subtle ERMs among special cases, such as those with uveitis.26 It follows that, theoretically, studies using both photography and OCT should detect more persons with ERMs. However, we unexpectedly found that two studies using OCT produced much lower prevalence rates of CMR, PMF and any ERM than the others without using it. A hypothesis explaining this apparent contradiction might be that OCT may exclude ERM suspects based on colour retinal images. For example, OCT is capable of differentiating ERM from posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), another condition that frequently affect the elderly and resemble CMR on colour retinal images. Further research is needed to assess the performance and cost-effectiveness of OCT in diagnosing ERMs prior to its adoption as the gold-standard test for epidemiological studies across the board.

For pooled risk estimates, our data showed that only age and sex were significantly associated the risk of any ERMs. Older and female individuals had higher risk of ERM from the meta-analysis (OR=1.19 and 1.34, respectively). With increasing age of the global population, ERM needs to be considered in a similar vein as AMD, a condition that significantly affects the ageing population. In terms of systemic and ophthalmic risk factors, no significant association was found between ERM and diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, BMI, myopia and early AMD.

Cigarette smoking, on one hand, is a well-documented risk factor for several eye diseases, including AMD27 and thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy.28 On the other hand, smoking can also serve as a protective factor against the development of pterygium.29 Our analysis convinced a negative association of ERM and smoking as well. This may be explained by a survival bias of smokers that cannot be excluded from cross-sectional analysis. So these findings should not discredit the importance of smoking cessation across populations.

Strengths of the present study include the large sample size, specific and inclusive nature of criteria for population-based studies and the inclusion of ERM subtype estimates (CMR and PMF). The pooled data provide a precise estimate of the ERM age-standard prevalence in the American and Asian-pacific population. However, our study contains several limitations as well. First, significant heterogeneity across studies existed in most of our analysis. Although we found that retinal image acquisition and grading methods might partly account for the heterogeneity, pooled prevalence estimates in each subgroup were still heterogeneous (all I2 >50%, tables 2 and 3). Second, the lack of studies from the African and European continents makes it difficult to estimate the global prevalence and magnitude of ERMs. Third, samples from different study designs had considerably different inclusion criteria, participant selection processes and study protocols. For example, sample populations were found to have considerably differences in proportions of subjects with cardiovascular disease or diabetes complications.9–11 Fourth, although ERMs, especially PMF, can cause moderate to severe visual impairment and metamorphopsias,4 most studies did not quantitatively analysed the association between ERMs and visual acuity. In this study, we are consequently unable to aggregate the data on their relationship.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our current study provides the first estimate of ERM and its different subtypes based on a pooled analysis of more than 40 000 participants from 13 studies in the US and the Western Pacific region. Our study shows that 9.1% of general population had some form of ERMs, 6.5% had CMR and 2.6% had the advanced form of PMF. These data suggest that ERMs have the potential to be a major cause of visual impairment. In some specific regions, such as Europe and Africa, robust evidence for the prevalence and risk of ERMs is absent. To address these gaps in the evidence, high-quality epidemiological research is needed that focuses specifically on these countries using standardised measures of diseases. Finally, we confirmed the significance and impact of two major factors, being age and sex, on the risk of ERMs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MH conceived and designed the study; WX and XC performed the literature search, study selection, data extraction and synthesis. WX prepared the draft manuscript; WY, ZZ and MH were involved in the revision and final preparation of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds of the State Key Laboratory of Ophthalmology (2016QN07), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81420108008) and Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, China (2013B20400003).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data are available.

References

- 1. Bu SC, Kuijer R, Li XR, et al. . Idiopathic epiretinal membrane. Retina 2014;34:2317–35. 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klein R, Klein BE, Wang Q, et al. . The epidemiology of epiretinal membranes. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1994;92:403–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koh V, Cheung CY, Wong WL, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors of epiretinal membrane in Asian Indians. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:1018–22. 10.1167/iovs.11-8557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheung N, Tan SP, Lee SY, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors for epiretinal membrane: the Singapore Epidemiology of Eye Disease study. Br J Ophthalmol 2016:bjophthalmol-2016-308563 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-308563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kawasaki R, Wang JJ, Sato H, et al. . Prevalence and associations of epiretinal membranes in an adult Japanese population: the Funagata study. Eye 2009;23:1045–51. 10.1038/eye.2008.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCarty DJ, Mukesh BN, Chikani V, et al. . Prevalence and associations of epiretinal membranes in the visual impairment project. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;140:288.e1–8. 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mitchell P, Smith W, Chey T, et al. . Prevalence and associations of epiretinal membranes. The Blue Mountains Eye Study, Australia. Ophthalmology 1997;104:1033–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duan XR, Liang YB, Friedman DS, et al. . Prevalence and associations of epiretinal membranes in a rural Chinese adult population: the Handan Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009;50:2018–23. 10.1167/iovs.08-2624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ye H, Zhang Q, Liu X, et al. . Prevalence and associations of epiretinal membrane in an elderly urban Chinese population in China: the Jiangning Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99:1594–7. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ng CH, Cheung N, Wang JJ, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors for epiretinal membranes in a multi-ethnic United States population. Ophthalmology 2011;118:694–9. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fraser-Bell S, Ying-Lai M, Klein R, et al. . Prevalence and associations of epiretinal membranes in latinos: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004;45:1732–6. 10.1167/iovs.03-1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Weerd M, Greving JP, de Jong AW, et al. . Prevalence of asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis according to age and sex: systematic review and metaregression analysis. Stroke 2009;40:1105–13. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.532218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rogers S, McIntosh RL, Cheung N, et al. . The prevalence of retinal vein occlusion: pooled data from population studies from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Ophthalmology 2010;117:313–9. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ahmad O, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez A, et al. . Age standardization of rates: a new who standard. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/paper31.pdf (accessed 20 June 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kawasaki R, Yasuda M, Song SJ, et al. . The prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in Asians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2010;117:921–7. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. . Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2012;35:556–64. 10.2337/dc11-1909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, et al. . A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010;1:97–111. 10.1002/jrsm.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kawasaki R, Wang JJ, Mitchell P, et al. . Racial difference in the prevalence of epiretinal membrane between Caucasians and Asians. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92:1320–4. 10.1136/bjo.2008.144626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miyazaki M, Nakamura H, Kubo M, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors for epiretinal membranes in a Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2003;241:642–6. 10.1007/s00417-003-0723-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhu XF, Peng JJ, Zou HD, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors of idiopathic epiretinal membranes in Beixinjing blocks, Shanghai, China. PLoS One 2012;7:e51445 10.1371/journal.pone.0051445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Agrawal R, Gupta P, Tan KA, et al. . Choroidal vascularity index as a measure of vascular status of the choroid: Measurements in healthy eyes from a population-based study. Sci Rep 2016;6:21090 10.1038/srep21090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meuer SM, Myers CE, Klein BE, et al. . The epidemiology of vitreoretinal interface abnormalities as detected by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: the beaver dam eye study. Ophthalmology 2015;122:787–95. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patel PJ, Foster PJ, Grossi CM, et al. . Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging in 67 321 Adults: Associations with Macular Thickness in the UK Biobank Study. Ophthalmology 2016;123:829–40. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ouyang Y, Heussen FM, Keane PA, et al. . The retinal disease screening study: prospective comparison of nonmydriatic fundus photography and optical coherence tomography for detection of retinal irregularities. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:1460–8. 10.1167/iovs.12-10727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nicholson BP, Zhou M, Rostamizadeh M, et al. . Epidemiology of epiretinal membrane in a large cohort of patients with uveitis. Ophthalmology 2014;121:2393–8. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Myers CE, Klein BE, Gangnon R, et al. . Cigarette smoking and the natural history of age-related macular degeneration: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1949–55. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shine B, Fells P, Edwards OM, et al. . Association between Graves’ ophthalmopathy and smoking. Lancet 1990;335:1261–3. 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91315-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rong SS, Peng Y, Liang YB, et al. . Does cigarette smoking alter the risk of pterygium? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55:6235–43. 10.1167/iovs.14-15046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014644supp001.pdf (64.1KB, pdf)