Abstract

Patient: Female, 55

Final Diagnosis: Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography biliary drain infection with Elizabethkingia meningoseptica

Symptoms: Right upper quadrant abdominal pain

Medication: IV Ciprofloxacin 400 mg/12 hrs

Clinical Procedure: None

Specialty: Surgery and Internal Medicine

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (E. meningoseptica) is an aerobic Gram-negative bacillus known to thrive in moist environments, and is now recognized as a hospital-acquired infection, being found to contaminate hospital equipment, respiratory apparatus, hospital solutions, water, and drainage systems. Nosocomial infection with E. meningoseptica occurs in immunocompromised patients, requires specialized identification methods, and is resistant to conventional antibiotics. We report a case of E. meningoseptica infection arising from a percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) tube.

Case Report:

A 55-year-old Saudi woman underwent liver transplantation. The post-operative period immediately following transplantation was complicated by anastomotic biliary stricture and bile leak, which was managed with percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) with PTBD. She developed right upper quadrant abdominal pain, and her ultrasound (US) showed a sub-diaphragmatic collection. Microbial culture from the PTBD tube was positive for E. meningoseptica, which was treated with intravenous ciprofloxacin and metronidazole. This case is the second identified infection with E. meningoseptica at our specialist center, fifteen years after isolating the first case in a hemodialysis patient. We believe that this is the first case of E. meningoseptica infection to be reported in a liver transplant patient.

Conclusions:

The emerging nosocomial infectious organism, E. meningoseptica is being seen more often on hospital equipment and medical devices and in water. This case report highlights the need for awareness of this infection in hospitalized immunocompromised patients and the appropriate identification and management of infection with E. meningoseptica.

MeSH Keywords: Biliary Tract Diseases, Corynebacterium, Cross Infection, Liver Transplantation, Saudi Arabia

Background

Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (E. meningoseptica), previously known as Flavobacterium meningosepticum and Corynebacterium meningosepticum, is a Gram-negative aerobic bacillus commonly found in the environment [1,2]. E. meningoseptica is known to thrive in moist environments and is now recognized as a hospital-acquired or healthcare-associated infection (HAI), being found to contaminate hospital equipment, water, and drainage systems [1,2]. Water-borne acquisition of E. meningoseptica infection has been demonstrated by epidemiological and molecular studies, including in critical care units [3].

Elizabethkingia spp. has a widespread distribution, can resist antibiotics, creates biofilms, and grows in moist environments [1,3]. E. meningoseptica has been shown to contaminate hospital equipment, including sink drains, respiratory apparatus, solutions, disinfectants, and hospital tap water [1,2]. Infection with E. meningoseptica is most common in immunocompromised patients and premature infants, with a reported mortality rate as high as 50% [4,5].

In the United States, approximately 5–9 cases of Elizabethkingia spp. infection are reported annually in each state, usually in healthcare settings [6]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that there are ongoing outbreaks of Elizabethkingia spp. infection in Wisconsin, Illinois, and also Michigan, in an outbreak that was initially recognized in November 2015 [7–9]. The cases reported in these states also include the first reported outbreak of E. anopheles and the largest known outbreak of Elizabethkingia spp. recorded in the United States. [6–8].

Currently, in Saudi Arabia, there is a lack of accurate epidemiological data on the incidence of outbreaks of hospital infection with Elizabethkingia spp., including E. meningoseptica. Further studies are needed to clarify the epidemiology, risk factors, signs and symptoms, as well as treatment and antimicrobial susceptibility of different strains of this organism.

We report a case of E. meningoseptica arising from a PTBD tube in a patient who was immunocompromised following liver transplantation. A brief literature review of cases of E. meningoseptica is presented to emphasize awareness of the diagnosis and management of this emerging infection.

Case Report

A 55-year-old Saudi woman, who was known to have end-stage liver disease due to cryptogenic cirrhosis, presented to the emergency department of our hospital in Riyadh, on 20th August 2015, with a one-day history of fever and cough, progressive lower limb edema, and abdominal distention. She had type 2 diabetes mellitus and was taking oral metformin 500 mg twice daily, and was treated for hypertension with oral amlodipine 5 mg, once daily. She was a non-smoker, did not consume alcohol, and had no history of drug abuse. She was admitted to hospital for one week under the liver transplantation team for further management.

On admission, her temperature was 37.7°C, heart rate of 111 beats per minute and respiratory rate of 26 breaths per minute, with normal blood pressure and oxygen saturation on breathing room air. Laboratory investigations showed a mild peripheral blood leukocytosis (12.3×109/L), platelets (41×109/L), albumin (26 g/L), bilirubin (47 µmol/L), and creatinine (59 µmol/L). A screen for infection included examination of blood, sputum, urine, and ascitic fluid. Chest X-ray showed right-sided pleural effusion, most likely representing hydrothorax with possible consolidation. She was commenced empirically on antibiotics and the dosage of her diuretics was increased. Six liters of ascitic and pleural fluid were drained. Urine culture was found to be positive for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B) that was sensitive to antimicrobials. Her clinical condition improved dramatically following treatment. Repeated chest X-ray showed reduction in the right hydrothorax. She was discharged home in good clinical condition. Her discharge medications included; a five-day course of oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg/12 hrs, oral lasix 20 mg, and a course of multivitamin tablets.

A month later, the patient was admitted to our hospital for an elective liver transplant, with a live organ donation from a relative. She underwent total hepatectomy and transplantation using a full right lobe graft. She had three biliary anastomoses, and her arterial anastomosis was repeated twice due to procedural difficulty. She required transfusion of 12 units packed red blood cells and was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) following liver transplantation.

In ICU, the patient was extubated after 24 hours. However, two days later she was re-intubated for another 24 hours due to the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). When her clinical condition had stabilized, she was moved to the general ward, and she was commenced on immunosuppressive therapy that included oral tacrolimus 1mg, oral mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg, and oral prednisolone 5mg.

The post-operative period was also complicated by an anastomotic biliary stricture and bile leak, which was managed by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) using an internal-external biliary catheter, with a pigtail catheter used for drainage of an intra-abdominal bile collection. The drains were kept in place for a few weeks until the drain output became minimal. The pigtail catheter was removed, and the internal-external PTBD catheter was left in place.

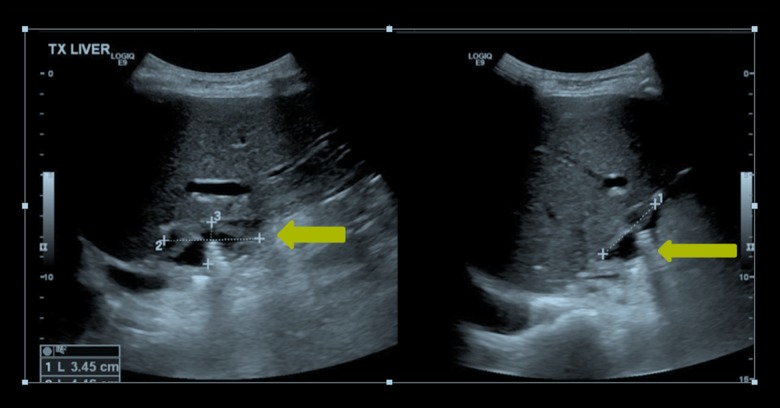

Three weeks later, the patients developed right upper quadrant abdominal pain without fever or vomiting. There was no change in peripheral blood leukocyte count, bilirubin, ALT or alkaline phosphatase levels when compared with baseline values, but her C-reactive protein (CRP) increased from 65.1 mg/L to 155.3 mg/L. Ultrasound of the abdomen showed a right-sided sub-diaphragmatic collection measuring 3.4×4.4×2.0 cm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ultrasound of the abdomen. A right-sided, sub-diaphragmatic collection measuring 3.4×4.4×2.0 cm is shown.

A septic screen included sampling and culture from blood, urine, biliary drain fluid, and the abdominal collection. The patient was commenced empirically on intravenous (IV) meropenem 20 mg/kg every 8 hrs. The culture from the PTBD catheter was positive for Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (E. meningoseptica), a multidrug-resistant organism.

Based on the antimicrobial sensitivity, IV meropenem was changed to IV ciprofloxacin 400 mg/12 hrs and metronidazole with a loading dose of 15mg/kg over one hour and a maintenance dose of 7.5 mg/kg every six hours (Table 1). After 48 hours, PTBD catheter fluid was sent for repeat cultures. Two days later, the repeat culture results were positive for moderate levels of E. meningoseptica.

Table 1.

Elizabethkingia meningoseptica antimicrobial susceptibility.

| Elizabethkingia meningoseptica | Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) dilution | MIC Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Piperacillin/tazobactam | 128 | Resistent |

| 2 | Ceftazidime | 64 | Resistent |

| 3 | Gentamicin | 16 | Resistent |

| 4 | Tobramycin | 16 | Resistent |

| 5 | Amikacin | 64 | Resistent |

| 6 | Cefipime | 64 | Resistent |

| 7 | Imipenem | 16 | Resistent |

| 8 | Meropenem | 16 | Resistent |

| 9 | Ciprofloxacin | 0.6 | Sensitive |

| 10 | Colistin | 16 | Resistent |

| 11 | Minocycline | 1 | Sensitive |

| 12 | Tigecycline | 4 | Sensitive |

| 13 | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 40 | Sensitive |

The patient’s clinical condition improved and her abdominal pain resolved. A decision was made to continue the antibiotics for a total of two weeks. After two weeks, the patient was asymptomatic with a normal peripheral blood leukocyte count (9×109/L), and her CRP dropped to 30 mg/L. Repeat fluid cultures from the PTBD catheter were negative. On follow-up, there were no complications from the antibiotic treatment.

Discussion

Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (E. meningoseptica) (formerly Chryseobacterium meningosepticum) is a member of the genus Chryseobacterium and is a non-motile, non-fastidious, catalase-positive and oxidase-positive, aerobic, glucose non-fermenting, Gram-negative bacillus that was first described by Elizabeth King in 1959 [3,6]. E. meningoseptica is commonly present in the soil, saltwater, freshwater, dry or moist clinical environments, medical equipment surfaces, intravenous lipid solutions, and municipal water supplies, including those that have been adequately chlorinated [3,6]. E. meningoseptica is associated with high mortality rates (up to 50%), partly because of the multidrug resistance of the organism [9]. However, unless patients have immunological or other susceptibility to infection, E. meningoseptica is an organism of low pathogenicity in humans [9]. Patients who may be vulnerable to infection with E. meningoseptica include preterm infants, the immunocom-promised, and those on antibiotics or in critical care units [9].

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have reported that there are ongoing outbreaks of Elizabethkingia spp. infection in the USA [6–9]. The findings from the CDC have shown that the majority of patients acquiring these infections are over 65 years old, and all patients have a history of at least one underlying serious illness [6–9]. In the year 2016, there were 63 cases of Elizabethkingia spp. infection resulting in 19 deaths [6–9]. Cities in the USA where these deaths occurred include Columbia, Dodge, Fond du lac, Milwaukee, Ozaukee, Racine, Sheboygan, Washington and Waukesha (Table 2) [6–9].

Table 2.

Wisconsin 2016 Elizabethkingia anophelis outbreak: Elizabethkingia infections believed to be associated with this outbreak reported to Division of Public Health (DPH)*, Case counts between November 1, 2015 and May 30, 2016 [7].

| Type of case | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Confirmed | 63 |

| Under investigation | 0 |

| Possible cases** | 4 |

| Total cases reported to Wisconsin DPH | 67 |

This investigation is ongoing [7]. Case counts may change as additional illnesses are identified and more cases are laboratory confirmed;

Hypoalbuminemia and infection associated with a central venous line have been reported to be risk factors in patients with E. meningoseptica, associated with an increased mortality rate [9].

Clinical presentations of E. meningoseptica infection include bacteremia (most common), eye infections, pneumonia, pericardial abscess, skin and soft tissue infection (such as cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis), intra-abdominal infection (for example, peritonitis in patients undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis), and surgical site infection (SSI) [10,11].

Elizabethkingia spp. are resistant to multiple antibiotics, including β-lactams, and may possess two different types of β-lactamases, class A extended spectrum β-lactamases and class B metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) [3,6]. MBLs result in resistance to carbapenems, which are currently used to treat infections due to multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria [3,6]. Two types of MBL, BlaB, and GOB have now been identified in E. meningosepticum, meaning that E. meningosepticum is resistant to multiple classes of antibiotic and may have varied resistance patterns that can only be determined by resistance testing in each case of infection [3,6]. Preventive measures that should be taken in hospitals to regulate this challenging infection include active infection control, such as hyper-chlorination of water, as well as regular surveillance and inspection of hospital water tanks [7,11].

This case report has presented a case of E. meningoseptica infection arising from a percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) tube in a patient following liver transplantation. The patient was doing well until one month post-transplant when she experienced abdominal pain. Abdominal pain in a patient following liver transplantation can be attributed to multiple factors including transplant rejection, infection, biliary leak or obstruction, and graft failure. In this case, the patient was afebrile, most likely due to immunosuppressive therapy that included prednisone, which commonly masks fever. A full septic screen is therefore always recommended in this population of patients when symptoms arise, as infections in patients following transplantation can be life-threatening [12,13]. The findings of a study were reported in 2010 by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDKD) that showed that the causes of death after one year in patients following liver transplantation can be categorized as follows: 28% from hepatic causes, 22% due to malignancy, 11% from cardiovascular causes, and 9% due to infection [13].

Bacterial and fungal infections remain a common cause of death within the first year after liver transplantation [13,14]. Even patients who live for several years after a transplant are at significant risk of developing life-threatening infections [14]. Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides is a rare bacterium that has been shown to originate from a bile leak in a liver transplant recipient following prolonged treatment with vancomycin [14]. Juntermanns et al. described a case of a 55-year old man who died eight years after a liver transplantation after suffering from skin and soft tissue infections [15]. Earlier detection as well as earlier surgical and antibiotic interventions could have prevented the death of the patient [15].

Fungal infections pose as a severe and potentially fatal complication in liver transplant patients. A retrospective study of 23 post-liver transplant patients admitted to the ICU and diagnosed with fungal infection, showed Candida spp. was found in 17/23 patients, Aspergillus spp. was found in 4/23 patients, but with no difference in mortality between infection from these two fungal pathogens [16].

In 2009, a study that analyzed bacterial infections in the early period after liver transplantation in adults followed 83 patients for four weeks after liver transplantation [17]. A total of 913 samples were cultured according to standard microbiological procedures [17]. Out of 913 samples, there were 469 isolated strains: 70.6% were Gram-positive bacteria, 28.4% were Gram-negative bacteria, and 1.0% were yeast-like fungal strains [17]. Multi-drug resistant (MDR) strains of bacteria were found [17]. In total, there were 138 strains of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci (MRCNS), 10 of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), 80 of high-level aminoglycoside resistance (HLAR), and 19 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-positive strains were detected [18].

To our knowledge, this is the first case of E. meningoseptica in a liver transplant patient. There were multiple risk factors in our patient for acquiring E. meningoseptica that included immunosuppression, hypoalbuminemia, the presence of a PTBD, all which facilitate the growth of this nosocomial infection. There have been no previously reported cases of PTBD-associated E. meningoseptica infection. Because this case report showed few E. meningoseptica bacteria in culture, which reflects the high virulence of this bacterium.

Conclusions

Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (E. meningoseptica) is an emerging nosocomial infection that has become recognized as the cause of outbreaks of infection and infection of individual cases of hospitalized patients. This case report demonstrates the importance of screening and early detection of this infection. Given its resistance to multiple antibiotics, healthcare providers should be aware of infection control measures to prevent outbreaks and recurrence of E. meningoseptica. Management of cases of E. meningoseptica should be directed by the findings of microbial culture and sensitivity findings to ensure rapid and effective treatment of this potentially serious infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Mohammad al Sebayel, MD, Chairman, Department of Liver and Small Bowel Transplant and Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery; Carla Alvarez Mercado, Senior Assistant, Department of Liver and Small Bowel Transplant and Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Young SM, Lingam G, Tambyah PA. Elizabethkingia meningoseptica endogenous endophthalmitis – a case report. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3:35. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-3-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie Z, Zhou Y, Wang S, et al. First isolation and identification of Elizabethkingia meningoseptica from cultured tiger frog, Rana tigerina rugulosa. Vet Microbiol. 2009;138:140–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirby JT, Sader HS, Walsh TR, Jones RN. Antimicrobial susceptibility and epidemiology of a worldwide collection of Chryseobacterium spp.: Report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997–2001) J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:445–48. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.445-448.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Issack MI, Neetoo Y. An outbreak of Elizabethkingia meningoseptica neonatal meningitis in Mauritius. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:834–39. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee C, Chen P, Wang L, et al. Fatal case of community-acquired bacteremia and necrotizing fasciitis caused by Chryseobacterium meningosepticum: Case report and review of the literature. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1181–83. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.1181-1183.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) About Elizabethkingia. Updated March 30th 2016. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/elizabeth-kingia/about/index.html.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Wisconsin 2016 Elizabethkingia anophelis outbreak. Updated May 17th 2017. Available from: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/disease/elizabethkingia.htm.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS) Investigates Bacterial Bloodstream Infections. Updated March 2nd 2016. Available from: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/news/releases/030216a.htm.

- 9.McQuiston J. Deadly midwest outbreak of Elizabethkingia. Medscape. Updated April 1st 2016 April. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/861096.

- 10.Pereira GH, de Oliveira Garcia D, Abboud CS, et al. Nosocomial infections caused by Elizabethkingia meningoseptica: an emergent pathogen. Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17(5):606–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ratnamani MS, Rao R. Elizabethkingia meningoseptica: Emerging nosocomial pathogen in bedside hemodialysis patients. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2013;17(5):304–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.120323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shinha T, Ahuja R. Bacteremia due to Elizabethkingia meningoseptica. IDCases. 2015;2:13–15. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watt KDS, Pedersen RA, Kremers WK, et al. Evolution of causes and risk factors for mortality post-liver transplant: Results of the NIDDK long-term follow-up study. Am J Transplantation. 2010;10:1420–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tholpady SS, Sifri CD, Sawyer RG, et al. Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides blood stream infection following liver transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2010;15:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juntermanns B, Radunz S, Heuer M, et al. Fulminant septic shock due to Clostridium perfringens skin and soft tissue infection eight years after liver transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2011;16:143–46. doi: 10.12659/aot.882009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marzaban R, Salah M, Mukhtar AM, et al. Fungal infections in liver transplant patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Ann Transplant. 2014;19:667–73. doi: 10.12659/AOT.892132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawecki D, Chmura A, Pacholczyk M, et al. Bacterial infections in the early period after liver transplantation: Etiological agents and their susceptibility. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15(12):CR628–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]