Abstract

3-Acetonyl-3-hydroxyoxindole (AHO) induces systemic acquired resistance (SAR) in Nicotiana. However, the underlying molecular mechanism is not well understood. To understand the molecular regulation during SAR induction, we examined mRNA levels, microRNA (miRNA) expression, and their regulatory mechanisms in control and AHO-treated tobacco leaves. Using RNA-seq analysis, we identified 1,445 significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) at least 2 folds with AHO treatment. The DEGs significantly enriched in six metabolism pathways including phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis for protective cuticle and wax. Key DEGs including PALs and PR-10 in salicylic acid pathway involved in SAR were significantly regulated. In addition, we identified 403 miRNAs belonging to 200 miRNA families by miRNA sequencing. In total, AHO treatment led to 17 up- and 6 down-regulated at least 2 folds (Wald test, P < 0.05) miRNAs (DEMs), respectively. Targeting analysis implicated four DEMs regulating three DEGs involved in disease resistance, including miR156, miR172f, miR172g, miR408a, SPL6 and AP2. We concluded that both mRNA and miRNA regulation enhances AHO-induced SAR. These data regarding DEGs, miRNAs, and their regulatory mechanisms provide molecular evidence for the mechanisms involved in tobacco SAR, which are likely to be present in other plants.

Introduction

Systemic acquired resistance (SAR) is an induced defense response that confers long-lasting protection against a broad spectrum of pathogen infections1,2. Localized treatment of plants with activators, compounds controlling disease without directly affecting the pathogen, results in the development of enhanced resistance against pathogens in the entire plant. Resistance induced by such activators is generally characterized by restriction of pathogen growth and decreased disease severity3,4. Only a few compounds have been found to induce SAR in plants2,5. One example, Acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM) stimulates the production of plant defense-related compounds6,7. However, no chemical treatment that can completely inhibit pathogen infection is available.

Natural products from plants have been proven to be a good resource in antimicrobial research, because plants have already evolved multiple mechanisms to selectively suppress pathogens by production of secondary metabolites with antimicrobial activities. 3-Acetonyl-3-hydroxyoxindole (AHO), a derivative of isatin, has been isolated from extracts of Strobilanthes cusia 8. AHO induces resistance in tobacco plants against infection with tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), the fungal pathogen Erysiphe cichoracearum (powdery mildew) and tospoviruses9, possibly through the salicylic acid pathway-mediated SAR8. However, the molecular mechanism of how AHO induces SAR has not been fully elucidated.

Plants have inducible defense mechanisms to protect from pathogen attacks. The inducible physiological defense of plants often includes rapid and localized cell death known as the hypersensitive response (HR), which is mediated either by gene interaction between a plant resistance (R) gene and a pathogen avirulence (Avr) gene or by the binding of a nonrace-specific elicitor, such as elicitin, to a putative receptor10. In addition, redox regulators, the mediator complex, transcription factors, endoplasmic reticulum-resident proteins, and DNA repair proteins also play critical roles in SAR4. To date, only a few genes have been shown to be involved in plant SAR, including gene expression that leads to increased salicylic acid (SA)1,11–13. A transcriptional co-activator encoded by the gene NPR1 plays a role in the SA signaling during basal resistance against pathogens14. Pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins are also in the SA signaling pathway, and some are also induced by various abiotic stresses15, and AHO-induced SAR increases PR expression in tobacco8. PRs are known to function in cell wall rigidification, signal transduction and antimicrobial activity16. Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) is a key enzyme for SA synthesis17. AHO-induced plant disease resistance is accompanied by increased PAL activity and SA accumulation8. Jasmonic acid (JA) is known to trigger plant immunity18. The increased JA level during pathogen perception promotes the CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 (COI1) expression, which represses the expression of Jasmonate ZIM domain (JAZ) and promotes degradation of JAZ. Then JAZ’s repression on several transcription factors is released, which increases the expression of defense genes18. SAR and plant disease resistance are complicated biological processes involving numerous genes and proteins. These components deserve further investigation.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding RNAs that are 20–24 nucleotides in length19–21. miRNA functions as guide RNAs to direct the repression of their mRNA targets at post-transcriptional level. Some of these target genes include those involved in hormone signaling, responses to biotic stresses and response to abiotic stresses22–27. Studies have suggested that miRNAs function in the plant defense reaction. The precursor miRNA ptc-MIR408 suppresses the expression of PALs. MiRNAs regulate several plant hormone signaling pathways of SA, abscisic acid (ABA) and jasmonic acid (JA)18,27. Down-regulation of JA biosynthesis by miR319 promotes SA-mediated resistance responses27,28. MiRNAs regulate the expression of protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) and laccase29,30. MiR398 targets at enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD) which is involved in the synthesis of antibacterial substances31,32. Because of the conserved regulatory functions of miRNA, miRNA-guided post-transcriptional regulation is expected to be involved in the response to infections in most plants. Therefore, the identification of stress-associated miRNAs should help understand the regulation at miRNA level during AHO-induced SAR in tobacco.

RNA-seq technology has been widely used to discover key genes and quantifying gene expression. This include pathogen resistance genes in Brassica napus 15, key genes for nitrogen utilization in the tea plant33, and genes for sugar metabolism in date palm34. Because miRNAs recognize their mRNA targets via base paring, the mRNA targets can be predicted using bioinformatics software. Hence, integrated mRNA and miRNA analysis has proven to be an effective method for exploring the molecular network at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels in response to biotic and abiotic stresses in plants35–39.

To better understand the molecular network in AHO-induced SAR, we applied both RNA-seq for transcriptome analysis and miRNA-seq for miRNA analysis in our study. Our results suggested that the AHO induces SAR in tobacco, and we identified differentially expressed genes and differentially expressed miRNAs (DEMs) in SAR. We predicted the mRNA targets of DEM, and predicted the regulatory interactions between specific DEM and specific DEGs. Our results help to explain the molecular mechanisms of SAR at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Because aspects of SAR are evolutionarily conserved across species, our results should provide a useful resource for SAR investigations in other plants.

Results

Inhibitory effect of AHO on tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) disease

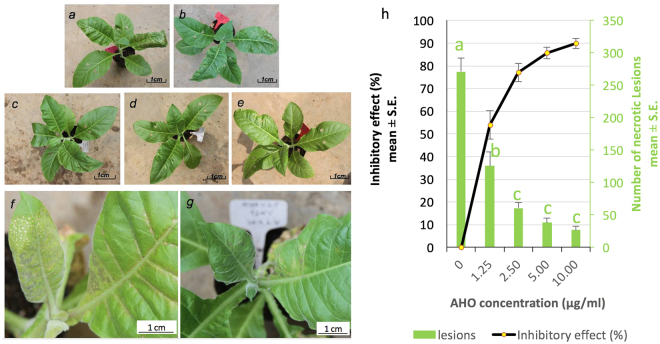

TSWV induces necrosis in tobacco plants7. To evaluate the inhibitory effect of AHO on TSWV, we inoculated N. tabacum K326, treated with different concentrations of AHO, with TSWV and recorded the disease symptoms. Our results showed that typical necrotic lesion symptoms caused by TSWV appeared in leaves after five days of inoculation in control plants (Fig. 1). After 15 days, more necrosis was observed in veins, old leaves, and the newly developed leaves in the control plants. In contrast, significantly less necrosis (ANOVA test P < 0.01) appeared on the AHO-treated leaves, especially in the treatment groups that received a high concentration of AHO treatment groups (Fig. 1f–g). The 10 µg/ml AHO treatment had an inhibitory rate of 89.9% on TSWV symptoms (Fig. 1, Table S1). Taken together, we concluded that AHO-treated plants had a significantly less TSWV infection than the control, thus suggesting that AHO induced SAR.

Figure 1.

Tobacco plants were sprayed with equal amounts of DMSO solution with different concentrations of AHO. Tomato spotted wilt virus was then inoculated mechanically on two middle leaves of each of three to five plants 24 hours after spraying. Photos were obtained after five days. (a–e) represents the tobacco plant treated with 0, 1.25, 2.5, 5.0 and 10.0 µg/ml AHO, respectively. (f,g) shows detailed infection in leaves of control and plants treated with 10 µg/ml AHO. Image h represents the inhibitory effect was calculated as the percent of (the total necrotic lesions in each control plant – that in each AHO-treated plant)/the total number of necrotic lesions in each control plant × 100%. One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis between treatment and control. Letter a, b and c in image (h) represent significance level at 0.01 compared with each other.

RNA-seq assembly and gene annotation for N. tabacum K326

To understand gene expression during AHO-induced SAR, we examined the transcriptomes in leaves of N. tabacum treated with 0 or 10 µg/ml AHO, by using Illumina HiSeq 2500 RNA-seq technology. A total of 83,753,496 clean 100-bp paired-end reads with quality Q30 > 91% were generated. To get the transcriptome accurately, we used two transcript assembling methods, the reference sequence guided and de novo assembly, to construct the transcript. The very recent updated N. tabacum K326 assembly40 was used as the reference to guide transcript assembly, and this method generated 99,547 transcripts from 66,700 super gene loci by using software Hisat and StringTie according to previously described protocols41. The gene number obtained here is close to the estimate number 69,50040. Of these gene loci, 37,759 (57%) were identical to existing gene annotation40. On average, each gene produced 1.4 transcripts. 85,461 (26%) and 35,675 (16%) novel exons and intron were found compared with existing genome annotation40, respectively. While de novo assembling with the Trinity software (version Trinityrnaseq_r20160317) according to the published protocol42 generated 236,647 transcripts belonging to 95,422 predicted unigenes, of which 26,972 were longer than 600 bp. The N50 length of transcripts from both methods were very similar, 1,775 bp in de novo assembly and 1,791 bp in reference guided assembly (Table S2). Comparison of transcription length revealed that de novo assembly generated more short transcripts than reference guided assembly (Fig. 2a), especially in <600 bp transcripts (Table S2). For both methods, more than 74% of the reads can be pair-mapped into transcripts or genome reference concordantly. The RNA-seq reads and assembly information have been deposited at NCBI and are publicly available under Bioproject number PRJNA342398 and accession number GFCB01000000, respectively. All unigenes from de novo transcripts were then used to search, via BLAST (threshold E-value 10-5), against each of the seven databases of NR, Swissprot, GO, COG, KOG, Pfam, and KEGG for annotation. The reference annotation of N. tabacum K326 at NCBI was chosen as the priority if available. By this analysis, a final total 37.8% of the unigenes were assigned a functional annotation from the best BLAST hit from at least one database, and the annotated transcript are mainly longer (>300 bp) transcripts (Table S3).

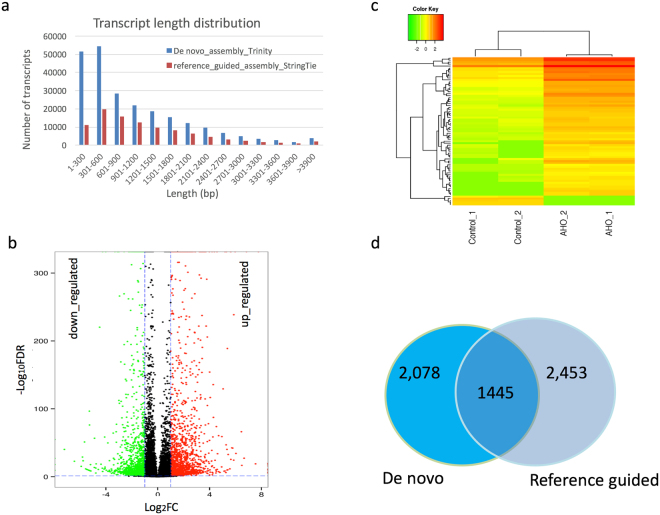

Figure 2.

Transcripts length and AHO induced differential gene expression in N. tabacum leaves. Image (a) shows the comparison of length distribution of transcripts which were de novo assembled and referenced guided assembly. Image (b) presents the differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05 and > = 2-fold change). Image (c) presents genes expression with at least 4-fold changes in gene expression with AHO treatment compared with control. Color represents the level of expression in FPKM after log2 transformation. _1 and _2 represent the two experimental repeats. Image (d) represents the shared DEGs from both assembly analyses.

Differential transcript levels in response to AHO

To reveal the DEGs in SAR induced by AHO, we measured transcript levels in fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads (FPKM) from RNA-seq data. Then, we compared the differentially expressed transcripts. After AHO treatment, 3,523 de novo unigenes in leaves were identified as DEGs with at least 2-fold change (false discovery rate <0.05) by using the previously described protocol42. Of these, 1,971 and 1,552 genes were up- and down-regulated, respectively (Fig. 2b). Further analysis revealed that 75 genes displayed at least 4-fold changes. Of these genes, 70 genes exhibited increased transcript level, whereas five transcripts exhibited decreased level (Fig. 2c). While from the reference guided assembly, we found 3,898 DEGs with at least 2-fold change (Wald test, P < 0.05) by using the tool DESeq243. Of these, 2,150 and 1,748 genes were up- and down-regulated, respectively. Of the two sets of assembled DEGs, 1,445 DEGs were shared though they were constructed from different methods (Fig. 2d).

Functional analysis of differentially expressed genes

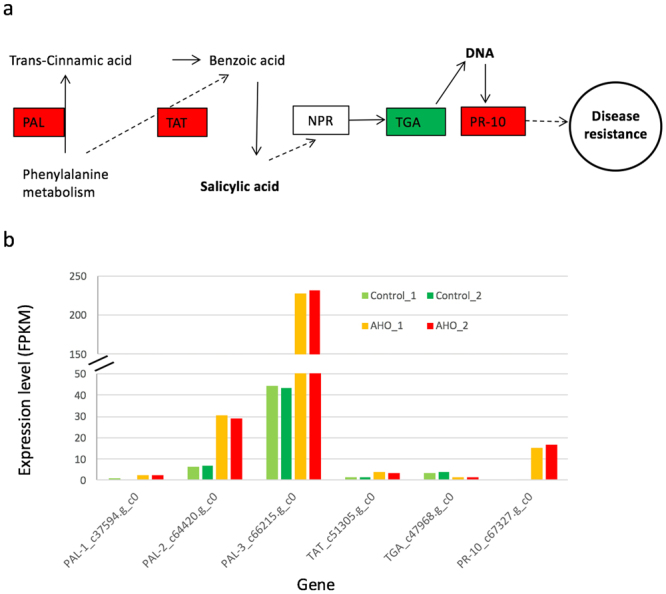

To better understand the function of the DEGs detected between the AHO-treated and control samples, we mapped the shared 1445 DEGs into the KEGG pathway database and identified enriched pathways by using the tool KAAS44. The DEGs were significantly enriched (hypergeometric test, P < 0.05) in six KEGG pathways in plants by using R package GOseq45. The enriched pathways included phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (KEGG pathway ID ko00940), sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis for protective cuticle and wax46 (KEGG pathway ID ko00909), biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (KEGG pathway ID ko01110), and photosynthesis - antenna proteins (KEGG pathway ID ko00196), etc (Table 1). As the phenylalanine involved in phenylpropanoid metabolism and is the substrate molecule for SA biosynthesis12,47, we mapped the DEGs to the SA pathway (KEGG map ID 04075)48 in Arabidopsis and found the homologous gene in tobacco (Fig. 3a). We identified three homologs (c37594.g_c0, c64420.g_c0 and c66215.g_c0) of PAL genes in SA biosynthesis, and the PALs expression was up-regulated (Fig. 3b). We also identified an up-regulated homolog (c51305.g_c0) of tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT) gene known for SA synthesis, and an up-regulated pathogen-related gene PR-10 homolog (c67327.g_c0) in the SA pathway, consistent with that reported previously49. The homolog of transcription factor TGA known to be involved in the SA pathway50 was down-regulated. In addition to SA, we assessed the transcript level for homologous genes involved in JA pathway and found only the JAZ gene (c64585.g_c0) was up-regulated while level of other genes like COI1 in this pathway were not changed.

Table 1.

Enriched differentially expressed genes in pathways at KEGG database.

| Pathway ID | over_represented P value | under_represented P value | Number of DEGs | Number of total genes | Pathway Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ko04111 | 0.002 | 1 | 22 | 26 | Cell cycle |

| ko00196 | 0.003 | 0.999 | 28 | 39 | Photosynthesis - antenna proteins |

| ko04113 | 0.009 | 0.999 | 14 | 16 | Meiosis |

| ko00940 | 0.992 | 0.02 | 51 | 114 | Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis |

| ko00909 | 0.992 | 0.02 | 6 | 29 | Sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis |

| ko01110 | 0.999 | 0.002 | 90 | 206 | Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites |

Enrichment analysis was conducted using length-bias corrected statistical method from R package GOseq45.

Figure 3.

Regulation of genes in salicylic acid pathway. The putative pathway (image a) was modified from KEGG pathway 04075 (version 9/6/16). Red and green represents the differentially up-regulated and down-regulated gene expression (image b) with AHO treatment in N. tabacum K326, respectively. Boxed are proteins or enzymes encoded by corresponding genes with same name.

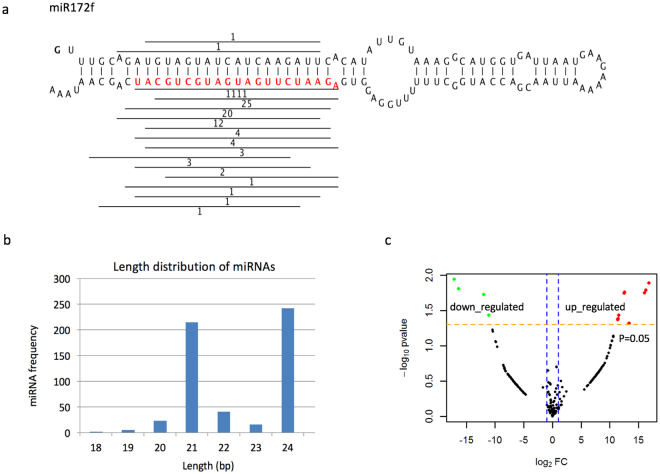

miRNA identification and its abundance measurement

To reveal the role of miRNAs in the SAR induced by AHO, we sequenced all miRNA candidates with the Illumina GAIIx (Illumina, USA) platform and obtained 15.4 million and 15.8 million single-end reads from the control and AHO treatment, respectively. To increase the accuracy of miRNA identification, we combined all read data and the publicly available genome assembly of N. tabacum K326 as a reference to mine the miRNA candidates with miRPlant software (version 4)51. After removing rRNAs, tRNAs and snoRNAs from among the candidates by using Blastn tool, we identified 403 miRNAs (Fig. 4a) belonging to 200 miRNA families (Table S4). These identified miRNAs were supported by robust genomic sequence and mapped miRNA reads. Therefore, the miRNA set identified was more accurate than that previously reported from genomic DNA in N. tabacum 52,53. After comparing the results, we identified 36 conserved miRNA families that were present in miRbase (version 21), whereas 164 miRNA families from our dataset were absent, thus suggesting that most of the miRNAs identified from N. tabacum K326 in this study were novel (Table S4). The 21-bp and 24-bp miRNAs were most abundant (Fig. 4b). Multiple members of the same miRNA family were discovered in the study. miR5303, novel107, miR156, miR166 and miR396 had 32, 24, 23, 14 and 10 members in each family, respectively (Table S4). Multiple members of miR156, miR166 and miR396 have also been reported in a previous study54. All other novel miRNA families had fewer than 5 members. We found that abundance of 115 miRNAs were at least 2-fold different in AHO treated versus untreated tobacco leaf controls. Although some previous studies only used 2 folds as a criterium to determine DEMs, we here used probability to increase the statistical power of the DEM identification with the tool DEseq243. We identified that 23 miRNAs exhibited a significant (Wald test, P < 0.05) abundance difference of at least 2 folds (Fig. 4c). Of these miRNAs, 17 and 6 DEMs members were significantly up-regulated and down-regulated, respectively (Fig. 4c, Table S4).

Figure 4.

miRNA identification, distribution and differential regulation. Image (a) presents the hairpin structure of miR172f as an example of identification of miRNAs from N. tabacum k326. The mature miRNA sequence is presented in red. The lines above or under the mature miRNA represent the matching reads in miRNA sequencing data, and the numbers represent the count of aligned reads. Image (b) presents the length distribution of miRNAs. Image (c) presents the distribution of differentially expressed miRNAs.

miRNA regulation of target gene expression

To explore the biological significance of DEMs, we analyzed the putative miRNA-target mRNA using the plant-specific prediction tool psRNATarget with strict parameter settings42. We predicted that 23 miRNA members targeted 16 DEGs in de novo assembly with AHO treatment (expectation cut off < = 2, Table S5). These miRNAs belonged into eight conserved and eight novel miRNA families (Table S5). Among these miRNAs, four members belonged DEMs and were predicted to regulate three DEGs (Table 2), thus indicating likely interactions of miRNA and mRNA in SAR (Table S5). We then compared with these target genes’ abundance in reference guided assembly, and revealed that all three genes were DEGs too with the same expression change patterns (Table 2).

Table 2.

Differentially expressed miRNAs and their differentially expressed target genes.

| Differential expressed miRNA | Differentially expressed gene | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | Log2(FC) | P value | Expression | Inhibition | Predicted target gene | FDR# P value* | Log2(FC) | Expression | Predicted gene function |

| miR156v | 12.5 | 0.02 | up | Cleavage | c32948.g_c0# N.11366* | 5E-04# 0.004* | −1.8# −1.4* | down | squamosa promoter-binding-like protein 6, transcription factor SPL6 |

| miR172f | 11.4 | 0.04 | up | Cleavage | c56968.g_c0# N.9090* | 3E-12# 0.002* | 2.4# 2.3* | up | AP2-like ethylene-responsive transcription factor TOE3 (AP2), binds to the GCC-box pathogenesis-related promoter element |

| miR172g | 11.4 | 0.04 | up | Cleavage | up | ||||

| miR408a | −11.1 | 0.03 | down | Translation | c23376.g_c0# N.38165 | 6E-112# 4E-06* | 2.1# 3.7* | up | a blue protein with copper ion binding function for electron transport |

Change was supported by transcript levels in both de novo assembling assay (#) and reference guided assembly assay (*). FDR represents false discovery rate. The predicted target gene marked by # or * are the same gene from corresponding assembly method.

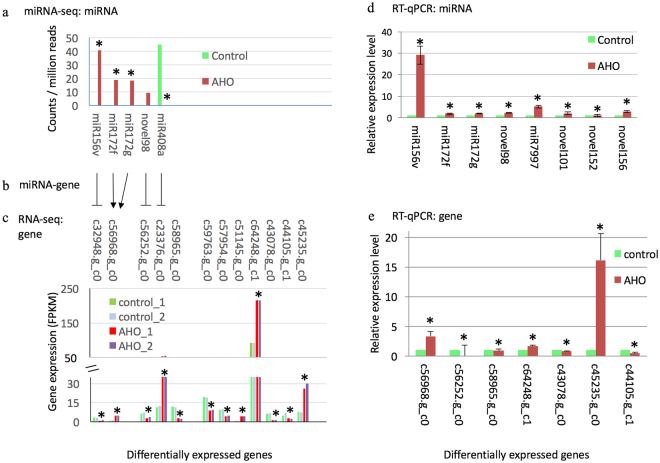

Of the three targeted DEGs, two genes were found to encode transcription factors, while the other gene encoded a protein with copper ion binding function (Table 2). We observed two patterns of miRNA-targeted gene expression. Pattern A. One miRNA targeted only one target DEG (Table 2). We predicted that increased miR156v levels are at least partly responsible for the down-regulation of DEG c32948.g_c0 during SAR (Fig. 5a,c). Gene c32948.g_c0 is predicted to encode transcription factor SPL6, a required key transcriptional regulator in resistance to TMV in tobacco and against Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis 55. The miR156v down-regulation on SPL6 in SAR is consistent with previous finding in pathogen defense in Arabidopsis 56 (Table 2, Fig. 5a,b,c). MiRNA 408a was down-regulated while its predicted targeted DEG c23376.g_c0 exhibited up-regulated transcript levels after AHO treatment (Table 2, Fig. 5a,b,c). Gene c23376.g_c0 encodes a predicted protein with copper ion binding activity in electron transport, which has been proposed to be involved in redox reactions occurring during primary defense responses in plants57. Pattern B. Several miRNAs appear to target one DEG. Three members in the miR172 family have the structural properties that would allow them to regulate DEG c56968.g_c0, encoding an AP2-like ethylene-responsive transcription factor (AP2) which has been predicted to bind to the GCC-box pathogenesis-related promoter element and to respond to environmental stimuli58,59. Only abundance of miRNA172g and miRNA172f were significantly increased (>2 folds and Wald test, P < 0.05) after AHO treatment. The relationship is that the expression of DEG c56968.g_c0 was increased although miRNA172g and miRNA172f were up-regulated (Table 2, Fig. 5a,b,c), suggesting that greater transcription of DEG c56968.g_c0 after AHO treatment overcomes the higher levels of post-transcriptional inhibition of miRNAs for this locus.

Figure 5.

Expression of miRNAs and their target transcripts. Image (a) shows the DEMs abundance change in RNA-seq analysis with AHO treatment. Image (b) represents the potential regulation between miRNAs and their target genes. The T shape end and arrow represent the opposite or same regulation trend between miRNA and mRNA. Image (c) shows the DEGs level in RNA-seq analysis. Image (d) and (e) shows the relative expression levels of miRNA and mRNA transcript assessed by qRT-PCR, respectively. The relative level of qRT-PCR calculated by the delta-delta-CT method. Data is presented as mean ± standard error.

RT-qPCR validation of levels of mRNAs and miRNAs

We used real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) to validate the expression level of selected interesting DEGs and DEMs, including specific DEMs and its targeted DEGs (Table S6). We tested eight interesting DEMs including miR156v, miR172f, miR172g, novel98 etc. and seven interesting DEGs (c56968.g_c0, c58965.g_c0, c64248.g_c1, c43078.g_c0, c44105.g_c1, c45235.g_c0 and c56252.g_c0). The test included miRNA-target pairs including DEMs of miR172f and miR172g, and their target DEG c56968.g_c0. We also tested the miRNA novel98 with 10-fold change but statistically not significant (Wald test, P = 0.8) and its predicted target DEG c56252.g_c0. The same patterns of change in RNA levels were observed in qRT-PCR as that in the RNA-seq analyses (Fig. 5d and e). Interestingly, we found that the change of novel98 level in qRT-PCR was significantly, suggesting that it should pay caution to draw conclusion on expression level with a high fold change but no statistical significance (P > 0.05) in sequencing result.

Discussion

Some chemical compounds can induce SAR in plants1,2,5, and therefore can have wide applications in agriculture. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the induction of SAR by natural products extracted from plants have rarely been investigated. A previous study has revealed that the compound AHO induces SAR together with changes in PR-1 gene expression, salicylic acid content, and PAL activity8. Our study further investigates molecular mechanisms of AHO-induced SAR in N. tabacum. Here, we focused on the genome-wide regulation of gene expression, miRNA expression, and predicted interaction between miRNAs and mRNA-encoding genes. We confirmed that AHO induced SAR in N. tabacum through TSWV inhibition experiments, and obtained expressed gene profiles from these N. tabacum leaf tissues. The reference guided assembly detected a slightly higher transcripts number (99,549) than the estimated ~93,000 in the tobacco K326 draft genome60. In contrast, the de novo assembly generated 2.6 times transcripts belonging to 95,422 unigenes, which is a standard observation for de novo RNA-seq analysis because several unigenes can often be derived from a single protein-coding gene because of incompleteness RNA-seq data contig generation or transcript clustering. This can be inferred from more short transcripts in de novo constructed transcripts than the reference guided transcripts. The RNA levels of 75 genes was found to differ by more than 4 folds. A 4-fold change in RNA level suggests a dramatic increase or decrease in expression level caused by regulating gene expression up or down, but it can also be an outcome of changes in the stability of individual mRNAs.

In our analysis, more genes were found to increase their transcript levels than to decrease with AHO treatment. This finding suggests that AHO-driven SAR activated more gene expression, thereby increasing acquired resistance in plants. These up-regulated genes may play important roles in SAR and are worthy of further investigation. Our results revealed that the AHO-treatment and resultant SAR generated a complicated set of responses enriched by DEGs in six metabolism pathways, including phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (KEGG pathway ID ko00940), sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis for protective cuticle and wax46 (KEGG pathway ID ko00909), and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (KEGG pathway ID ko01110). Some DEGS were interesting because of they have been known as involving in SAR. A DEG example associated with unigenes ID c67327.g_c0 was up-regulated in tobacco leaves treated with AHO. This gene is annotated as encoding STH-2-like PR protein (also known as PR-10a49), which plays a crucial role against viral infection in hot peppers49. PR-10 gene expression is regulated by plant hormones and defense-related signaling molecules, including JA and SA61. We have previously observed increased SA in AHO-induced SAR8, which may have up-regulated PR-10 expression in this study. Phenylalanine is the source for SA biosynthesis through the PAL enzymatic pathway12,47. Here, we also identified that PALs, TAT genes involved in SA synthesis were up-regulated. This suggests these genes in SA pathway play roles in AHO-induced SAR, similar to their roles in plant response to pathogen.

The small non-coding RNAs called miRNAs regulate numerous aspects of post-transcriptional gene expressions and have potential applications in crop improvement62. However, the roles of miRNAs in SAR in plants are not fully characterized. Although studies have reported the discovery of miRNAs in N. tabacum 52,53, the miRNAs were found to be at a low confidence by automated evaluation in the miRBase database (version 21). The reason for this low confidence was the previous lack of Nicotiana genomic sequences for use in miRNA prediction. In this study, we used the publicly available N. tabacum K326 draft genome sequence as the reference to validate the mined miRNAs from K326. We mined the miRNAs and then aligned the miRNAs to genomic sequence to confirm their origin and to improve accuracy. We identified 403 miRNA members and categorized them into 200 families. The majority of miRNA are 21 or 24 nucleotides in size, as also seen in previous report16. Most of the miRNAs were novel, and some miRNAs, such as miR172, had multiple members. These data indicated that the miRNAs discovered here are more accurate and abundant than those previously reported. We further calculated miRNA abundance and identified 17 and 6 miRNAs that were up- and down-regulated significantly (Wald test, P < 0.05) in AHO-induced SAR, respectively. The DEMs identified here have higher confidence with the statistical power than most of other DEMs associated published articles which used only 2 folds of abundance change.

Plant miRNAs have conserved regulatory function. We explored the molecular network between miRNA and its target mRNA in SAR by predicting the miRNA and its targeted DEG. MiRNAs are known to functionally down-regulate target gene expression22–27, as reflected in pattern A, whereby one DEM is predicted to repress one DEG. We found predicted interaction in this category for miR156v and miR408a (Fig. 5a,b and c). We also predicted another pattern, pattern B, wherein multiple DEMs regulated one DEG, named c56968g_c0. The observed DEG level in pattern B may reflect the combined effects of multiple regulations. We did not identify miRNA targeting of reported genes8 that encode enzymes in the SA biosynthesis pathway or PR proteins.

We identified DEMs targeting DEGs that function in disease resistance, as supported by findings in other plants. We predicted two transcription factors SPL and AP2 are AHO-affected at the miRNA level, in agreement with that transcription factor mRNAs are the preferred targets of miRNAs10. In this study, the up-regulated miR156v is predicted to target the c32948.g_c0 gene, which encodes the transcription factor SPL6. Numerous SPL genes are post-transcriptionally regulated by miR15663,64. SPL is potentially involved in divergent signal transduction pathways mediated by auxin, gibberellin, ethylene and other plant hormones65. Hence, our study confirmed that miR156v plays a role in plant disease resistance potentially through down-regulating SPL6 expression. We predicted that miR172f and miR172g targeted AP2 (unigene ID c56968.g_c0). This regulation has been reported in plants66 and is involved in nodule formation by rhizobium infection in soybean57. Multiple miR172 members regulate AP2, and we found a net increase in miR172 levels that co-occurred with increased AP2 level. This finding indicated that miR172 does not greatly suppress the net level of the AP2 transcript. A similar phenomenon has been reported in which induced miR172 is associated with high levels of AP2 transcript but no AP2 protein in Arabidopsis 67. Early studies have confirmed that miR172 regulates expression of the target gene AP2 by cleavage of mRNA or translational inhibition68. Considering these results together, we hypothesize that miRNA172 may regulate AP2 at the level of translational repression rather than mRNA cleavage in AHO-induced SAR. As a key transcription factor, it is expected that AP2 will be regulated by many factors, including those that affect RNA level. Studies have revealed that plantacyanin-like (basic blue) protein is the target of miR40866,69. Here, we predicted that decreased miR408a targeted basic blue protein-like (DEG c23376.g_c0) which exhibited an up-regulation in mRNA level. The regulated protein may play a role in plant resistance through modulating the activities of oxido-reductase in the electron transport chain (Table 2). Future efforts are needed to undertake the extensive and challenging molecular genetics are needed to experimentally validate of the interplay of miRNA and mRNA target of miRNA156, 172 and miR408a.

The discussed DEGs and DEMs may be key players in AHO-induced SAR. However, it is also possible that the additional DEGs or DEMs may account for some of the AHO-induced SAR. In this regard, we identified several interesting DEGs in the AHO-treated tissues. For instance, the decreased expression of hexose carrier protein HEX6-like (DEG ID c58965.g_c0) (Table S5) could diminish the transport of hexose in AHO-treated leaves. The susceptibility of plants to disease is dependent on the sugar content in the leaf70, and sugars play an important role in the induction of defense responses71. A prerequisite for defense gene expression is a certain level of hexoses delivered by via a transporter72,73. As a consequence of perturbation of sugar metabolism, defense-related genes are activated, and SA levels are elevated, and SAR is consequently induced72. We also found that DEG c51145.g_c0 encodes P2C protein (Table S5). P2C plays a crucial role in the ABA signaling pathway, as shown by studies in Arabidopsis and P. patens 59,74. The increased expression of P5C (DEG c64248.g_c1) in our study is also consistent with that reported in N. benthamiana during pathogen infection75. We found that P5C was up-regulated by ~ 3 folds (Fig. 5c).

Conclusions

In summary, this is an initial report of gene regulations of AHO-induced SAR in the model plant N. tabacum K326. We generated transcriptome and miRNA sequence data for control and AHO-treated tobacco leaves and performed comprehensive analysis of the AHO-induced mRNAs and miRNAs. The results revealed DEGs potentially involved in AHO-induced SAR, including genes related to responses to plant hormone signal transduction, phenylalanine biosynthesis, pathogenesis-related protein biosynthesis and starch and sucrose metabolism. In addition, our analysis also identified miRNAs that may play important roles in AHO-induced SAR. Furthermore, potential regulatory interactions between specific miRNAs and their target transcripts were revealed. These findings provide valuable information regarding the roles of mRNA and miRNA at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels in AHO-treated plant N. tabacum. It will be vital to see how similar the patterns of differentially expressed genes, miRNAs and their regulatory will be associated with SAR in other crops.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and treatment

In an insect-free greenhouse, tobacco seeds of Nicotiana tabacum cv K326 were sown in seed pans containing a mixture of 50% (w/w) peat culture substrate, 40% (w⁄w) humus and 10% (w⁄w) perlite. Thirty to thirty-five days after seeding, seedlings were transplanted into pots (one plant per pot). Tobacco plants were cultivated to the 5~6-leaf stage before use in the experiments. Briefly, 0.1 g AHO was dissolved in 1 ml dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then diluted with distilled H2O to 1.25, 2.5, 5, or 10 μg/ml. DMSO without AHO was used as a control. Each tobacco plant was sprayed with 5 ml AHO solution or control solution. Three to five plants were used in each treatment. Two experimental repetitions were undertaken.

Inhibitory effect of AHO on tomato spotted wilt virus symptomology

Tomato spotted wilt virus was mechanically inoculated on the two middle leaves of each plant 24 hours after spraying. Three-five plants were used for each treatment. These plants were cultivated in the greenhouse for 15 days. The first time of necrotic lesions appeared on the leaves was recorded. The number of necrotic lesions was counted, and the inhibition percentage was calculated by using the following formula (the total number of necrotic lesions on each control plant-the total number of necrotic lesions on each AHO-treated plant)/the total number of necrotic lesions on each control plant × 100%.

RNA extraction and sequencing

For mRNA and miRNA analysis, all leaves were collected from each of three to five tobacco plants with 10 μg/ml AHO treatment or control at 6 h and were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The leaf samples of each treatment were stored at −80 °C until use. Leaf samples were pooled for the same treatment and ground into powder in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle. Total RNA was extracted from 80–120 mg powder by using TRIzol Reagent (Ambion) (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Shanghai, China, cat# 15596-026). The quality and quantity of total RNA were characterized on a 1% agarose gel and examined with a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). The RNA integrity number (RIN) was assessed by using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA, USA). The RIN of mRNA samples was greater than 8.0, and mRNA was used for subsequent Illumina library preparation. mRNA was enriched from 15 μg total RNA by using an NEBNext poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (NEB, cat# E7490L) and AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter, Inc., cat# A63881). mRNA was cleaved into short fragments by using buffer and then indexed by nucleotide barcode. Then, the sequencing library was prepared with an NEBNext mRNA Library Prep Master Mix Set for Illumina (NEB, cat# E6110L) and NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (NEB, cat# E7500). The library was then quantified by qRT-PCR using a Quantification Kit-Illumina GA Universal (Kapa, cat# KK4824). Paired-end 100-bp sequencing was performed for the qualified library on a HiSeq 2500 machine. Two duplicated experiments were conducted.

Transcript assembly, annotation and expression analysis

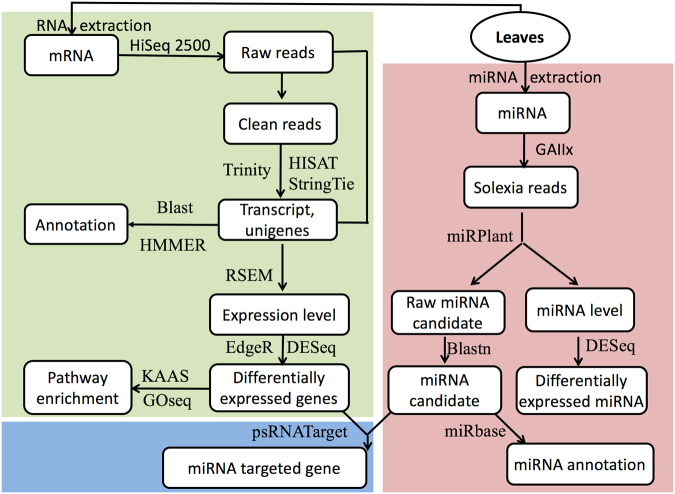

Pair-end PE-100-bp raw reads generated from Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencing were preprocessed to remove adaptor sequences, filter out reads with >5% unknown bases, and remove low-quality reads (>20% of the bases with a quality score of less than 10). The retained reads, called clean reads, from the same experimental group were combined and assembled de novo to construct transcripts with Trinity software (version Trinityrnaseq_r20160317, https://github.com/trinityrnaseq) followed described protocols42. Clean reads were mapped back to transcript assembly, and poorly supported transcripts were removed as described previously42. Unigenes were defined as the longest sequence in an assembly cluster42. RSEM76 (version 1.2.27, https://deweylab.github.io/RSEM/) was adopted to quantify the total expressed transcripts in FPKM (Fragments per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped reads) and raw counts. The R package EdgeR built in Trinity package42 was used to identify the differentially expressed mRNAs at least a 2-fold change and FDR value < 0.05. We also conducted a reference based assembling for the same batch of clean RNA-seq data by using HiSAT and StringTie followed published protocols41. The newest N. tabacum assembly V.4.5 was used as reference40. R package DEseq243 (version 1.16, https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html) was used to identify differentially expressed reference guided transcript and miRNA that exhibited at least a 2-fold change and P value < 0.05. Unigenes were then searched by Blatsn with an E-value threshold of E-5 against NR, SwissProt, GO, COG, KEGG and KOG databases and against Pfam database by HMMER with E-value of E-10. Online tool KAAS44 from KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/) was used to map expressed gene to K number and then convert to KO pathway number ID, called ko number, at database KEGG. The R package GOseq45 (http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/goseq.html) was used to conduct enrichment analysis on genes or miRNA the KEGG pathways at level P < 0.05. A schematic workflow of the analysis was presented (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

The workflow of mRNA and miRNA data analysis. The top left block in grass green shows the workflow of mRNA analysis. The bottom left block shows the workflow of prediction on miRNA and its mRNA target. The right block shows the workflow of miRNA analysis. The tools or software is given next to the line or pointer.

microRNA analysis

microRNAs were extracted with a mirVana™ miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and then used for library preparation with the Small RNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, SanDiego, CA, USA). miRNAs were sequenced by using the Solexa platform. Raw reads were first cleaned by using a corresponding Illumina process. Then, the cleaned reads were input into the software miRPlant77 (version 4, https://sourceforge.net/projects/mirplant/) to find miRNAs. The parameters were set to miR length 18–25 bp and minimum read count 4; other parameters were set to default. The adaptor sequence was 5′-AGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCT-3′, and the reference genome sequence of N. tabacum K326 was downloaded from NCBI (version http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AWOJ00000000.1/)78. Potential non-miRNAs were removed if they were identified in the SiRNA, tRNA, snoRNA and rRNA database (pfam version 11, http://pfam.xfam.org/) after a Blastn searches with the following settings: E-value 10-5, -W 4 -F -G 2 -q -4. The remaining candidates were considered as miRNA. To annotate and compare conserved or reported miRNAs, the existing miRNAs in the most recent database miRbase (version 21.0, www.mirbase.org) were downloaded and used to identify the conserved or reported tabacum miRNAs by using the Blastn tool with a maximum of two mismatches allowed. A miRNA family code was then assigned to the mined miRNA if similarity was found according to described criteria79 and was then manually confirmed. A schematic workflow of the analysis is presented in Fig. 6.

miRNA target analysis

Each miRNA target was predicted by using the tool psRNATarget80 (http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/) with a strict parameter maximum expectation of 2 and other default settings as follows: length for complementarity scoring (hspsize) 20; target accessibility (UPE) 25.0; flanking length around the target site for target accessibility analysis 17; range of central mismatch leading to translational inhibition 9–11 nt.

RT-qPCR analysis

Total RNA or miRNA was extracted from control or AHO-treated and pooled leaf samples of three to five plants used in RNA sequencing, respectively. There were at least three RT-qPCR reactions conducted for each sample. For mRNA expression analysis, the cDNA was generated using the HiScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit using random hexa-primers (Vazyme, China). For miRNA expression analysis, the stem-loop reverse transcription primers were designed as previously described81,82, and the reverse transcription reactions were performed as described for miRNA. qRT-PCR reactions were performed using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche, China) on a BIOER FQD-96A instrument. The tobacco actin gene was used as reference gene for the normalization of reactions in the mRNA analysis83, and a tobacco U6 sequence was used as the reference for data normalization in the miRNA analysis36. The relative expression of each sample was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method84. Primers used in these qRT-PCR analyses are presented in Supplementary Table S6.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Applied Basic Research Foundation of Yunnan Province (2013FB092; 2013FZ145); Yunling Scholars Program; Top Scientists Input Program (2013HA028); Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Projects (2012CH007); the Fund for Reserve Talents of Young and Middle-aged Academic and Technical Leaders of Yunnan Province (2015HB081).

Author Contributions

Y.C., X.W. and J.D. designed the study. Y.C., J.D., J.Y. and J.Z. conducted the experiments. X.W., Y.C. and M.Z. analyzed the data. X.W., Y.C. and J.B. prepared the manuscript. X.W., S.L., X.H., Z.Z. and Y.C. participated in the discussion.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Yongdui Chen and Jiahong Dong contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-12249-y.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhongkai Zhang, Email: zhongkai99@sina.com.

Xuewen Wang, Email: xwwang@uga.edu.

References

- 1.Durrant WE, Dong X. Systemic acquired resistance. Annual review of phytopathology. 2004;42:185–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gozzo F, Faoro F. Systemic acquired resistance (50 years after discovery): moving from the lab to the field. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 2013;61:12473–12491. doi: 10.1021/jf404156x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammond-Kosack KE, Jones JD. Resistance gene-dependent plant defense responses. The Plant cell. 1996;8:1773–1791. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu ZQ, Dong X. Systemic acquired resistance: turning local infection into global defense. Annual review of plant biology. 2013;64:839–863. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah J, Chaturvedi R, Chowdhury Z, Venables B, Petros RA. Signaling by small metabolites in systemic acquired resistance. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology. 2014;79:645–658. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeshita M, et al. Induction of antiviral responses by acibenzolar-s-methyl against cucurbit chlorotic yellows virus in Melon. Phytopathology. 2013;103:960–965. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-08-12-0188-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandal B, et al. Biological and molecular analyses of the acibenzolar-S-methyl-induced systemic acquired resistance in flue-cured tobacco against Tomato spotted wilt virus. Phytopathology. 2008;98:196–204. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-98-2-0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, et al. 3-Acetonyl-3-hydroxyoxindole: a new inducer of systemic acquired resistance in plants. Plant biotechnology journal. 2008;6:301–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yongdui Chen JZ, Wu K, Liu C, Xiao J, Li X. Jiahong dong, Hongguang Li. Field control effect of plant-derived natural product AHO on tospovirus diseases. Journal of Southern Agriculture. 2014;45:2167–2171. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hausser J, Zavolan M. Identification and consequences of miRNA-target interactions–beyond repression of gene expression. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2014;15:599–612. doi: 10.1038/nrg3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Rockett KS, Korner CJ, Pajerowska-Mukhtar KM. Salicylic acid signalling: new insights and prospects at a quarter-century milestone. Essays in biochemistry. 2015;58:101–113. doi: 10.1042/bse0580101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boatwright JL, Pajerowska-Mukhtar K. Salicylic acid: an old hormone up to new tricks. Molecular plant pathology. 2013;14:623–634. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith HB. Signal transduction in systemic acquired resistance. The Plant cell. 2000;12:179–181. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frazier TP, Xie F, Freistaedter A, Burklew CE, Zhang B. Identification and characterization of microRNAs and their target genes in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) Planta. 2010;232:1289–1308. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu J, et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis uncovers the complex genetic network for resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Brassica napus. Scientific reports. 2016;6:19007. doi: 10.1038/srep19007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi Y, Guo H, Li K, Liu W. Comprehensive analysis of differential genes and miRNA profiles for discovery of topping-responsive genes in flue-cured tobacco roots. The FEBS journal. 2012;279:1054–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z, Zheng Z, Huang J, Lai Z, Fan B. Biosynthesis of salicylic acid in plants. Plant signaling & behavior. 2009;4:493–496. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.6.8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campos ML, Kang JH, Howe GA. Jasmonate-triggered plant immunity. Journal of chemical ecology. 2014;40:657–675. doi: 10.1007/s10886-014-0468-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Bartel B. MicroRNAS and their regulatory roles in plants. Annual review of plant biology. 2006;57:19–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang B, Pan X, Cobb GP, Anderson TA. Plant microRNA: a small regulatory molecule with big impact. Developmental biology. 2006;289:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubio-Somoza I, Cuperus JT, Weigel D, Carrington JC. Regulation and functional specialization of small RNA-target nodes during plant development. Current opinion in plant biology. 2009;12:622–627. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin H. Endogenous small RNAs and antibacterial immunity in plants. FEBS letters. 2008;582:2679–2684. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sunkar R, Chinnusamy V, Zhu J, Zhu JK. Small RNAs as big players in plant abiotic stress responses and nutrient deprivation. Trends in plant science. 2007;12:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padmanabhan C, Zhang X, Jin H. Host small RNAs are big contributors to plant innate immunity. Current opinion in plant biology. 2009;12:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khraiwesh B, Zhu JK, Zhu J. Role of miRNAs and siRNAs in biotic and abiotic stress responses of plants. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1819:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, et al. Bacteria-responsive microRNAs regulate plant innate immunity by modulating plant hormone networks. Plant molecular biology. 2011;75:93–105. doi: 10.1007/s11103-010-9710-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Torres-Zabala M, et al. Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato hijacks the Arabidopsis abscisic acid signalling pathway to cause disease. The EMBO journal. 2007;26:1434–1443. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schweighofer A, Hirt H, Meskiene I. Plant PP2C phosphatases: emerging functions in stress signaling. Trends in plant science. 2004;9:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang ZMS, et al. prediction of microRNAs and their target genes in maize. Acta Agronomica Sinica. 2010;36:1324–1335. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2010.01324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP. Computational identification of plant microRNAs and their targets, including a stress-induced miRNA. Molecular cell. 2004;14:787–799. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sunkar R, Li YF, Jagadeeswaran G. Functions of microRNAs in plant stress responses. Trends in plant science. 2012;17:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W, et al. Transcriptome and metabolite analysis identifies nitrogen utilization genes in tea plant (Camellia sinensis) Scientific reports. 2017;7:1693. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01949-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Mssallem IS, et al. Genome sequence of the date palm Phoenix dactylifera L. Nature communications. 2013;4:2274. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qiao Y, et al. Integrated RNA-seq and sRNA-seq analysis reveals miRNA effects on secondary metabolism in Solanum tuberosum L. Molecular genetics and genomics: MGG. 2017;292:37–52. doi: 10.1007/s00438-016-1253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Q, et al. Integrated mRNA and microRNA analysis identifies genes and small miRNA molecules associated with transcriptional and post-transcriptional-level responses to both drought stress and re-watering treatment in tobacco. BMC genomics. 2017;18:62. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3372-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang M, et al. Integrated analysis of miRNA and mRNA expression profiles in response to Cd exposure in rice seedlings. BMC genomics. 2014;15:835. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng C, et al. Integrated RNA-Seq and sRNA-Seq analysis Identifies chilling and freezing responsive key molecular players and pathways in tea plant (Camellia sinensis) PloS one. 2015;10:e0125031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J, Zhang F, Li J, Chen JP, Zhang HM. Integrative Analysis of the microRNAome and Transcriptome Illuminates the Response of Susceptible Rice Plants to Rice Stripe Virus. PloS one. 2016;11:e0146946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards KD, et al. A reference genome for Nicotiana tabacum enables map-based cloning of homeologous loci implicated in nitrogen utilization efficiency. BMC genomics. 2017;18:448. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3791-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, Salzberg SL. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protocols. 2016;11:1650–1667. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haas BJ, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature protocols. 2013;8:1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome biology. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35:W182–185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome biology. 2010;11:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moses T, et al. OSC2 and CYP716A14v2 Catalyze the Biosynthesis of Triterpenoids for the Cuticle of Aerial Organs of Artemisia annua. The Plant cell. 2015;27:286–301. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.134486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vlot AC, Dempsey DA, Klessig DF. Salicylic Acid, a multifaceted hormone to combat disease. Annual review of phytopathology. 2009;47:177–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.050908.135202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silipo A, et al. The Elicitation of Plant Innate Immunity by Lipooligosaccharide of Xanthomonas campestris. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:33660–33668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506254200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaas LA, Marheine M, Sikorski J, Goker M, Schumacher HM. Impacts of pr-10a overexpression at the molecular and the phenotypic level. International journal of molecular sciences. 2013;14:15141–15166. doi: 10.3390/ijms140715141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson C, Boden E, Arias J. Salicylic Acid and NPR1 Induce the Recruitment of trans-Activating TGA Factors to a Defense Gene Promoter in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell. 2003;15:1846–1858. doi: 10.1105/tpc.012211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh A, Giri J, Kapoor S, Tyagi AK, Pandey GK. Protein phosphatase complement in rice: genome-wide identification and transcriptional analysis under abiotic stress conditions and reproductive development. BMC genomics. 2010;11:435. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo H, Kan Y, Liu W. Differential expression of miRNAs in response to topping in flue-cured tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) roots. PloS one. 2011;6:e28565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burklew CE, Ashlock J, Winfrey WB, Zhang B. Effects of aluminum oxide nanoparticles on the growth, development, and microRNA expression of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) PloS one. 2012;7:e34783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Komatsu K, et al. Functional analyses of the ABI1-related protein phosphatase type 2C reveal evolutionarily conserved regulation of abscisic acid signaling between Arabidopsis and the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant molecular biology. 2009;70:327–340. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9476-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cutler SR, Rodriguez PL, Finkelstein RR, Abrams SR. Abscisic acid: emergence of a core signaling network. Annual review of plant biology. 2010;61:651–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qamar A, Mysore KS, Senthil-Kumar M. Role of proline and pyrroline-5-carboxylate metabolism in plant defense against invading pathogens. Frontiers in plant science. 2015;6:503. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nersissian AM, et al. Uclacyanins, stellacyanins, and plantacyanins are distinct subfamilies of phytocyanins: plant-specific mononuclear blue copper proteins. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society. 1998;7:1915–1929. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jung JH, Lee S, Yun J, Lee M, Park CM. The miR172 target TOE3 represses AGAMOUS expression during Arabidopsis floral patterning. Plant science: an international journal of experimental plant biology. 2014;215–216:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Licausi F, Ohme-Takagi M, Perata P. APETALA2/Ethylene Responsive Factor (AP2/ERF) transcription factors: mediators of stress responses and developmental programs. The New phytologist. 2013;199:639–649. doi: 10.1111/nph.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sierro N, et al. The tobacco genome sequence and its comparison with those of tomato and potato. Nature communications. 2014;5:3833. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McGee JD, Hamer JE, Hodges TK. Characterization of a PR-10 pathogenesis-related gene family induced in rice during infection with Magnaporthe grisea. Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI. 2001;14:877–886. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.7.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Djami-Tchatchou AT, Sanan-Mishra N, Ntushelo K, Dubery IA. Functional Roles of microRNAs in Agronomically Important Plants-Potential as Targets for Crop Improvement and Protection. Frontiers in plant science. 2017;8:378. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen X, et al. SQUAMOSA promoter-binding protein-like transcription factors: star players for plant growth and development. Journal of integrative plant biology. 2010;52:946–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Preston JC, Hileman LC. Functional Evolution in the Plant SQUAMOSA-PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE (SPL) Gene Family. Frontiers in plant science. 2013;4:80. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martin RC, et al. The microRNA156 and microRNA172 gene regulation cascades at post-germinative stages in Arabidopsis. Seed Sci Res. 2010;20:79–87. doi: 10.1017/S0960258510000085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sunkar R, Zhu JK. Novel and stress-regulated microRNAs and other small RNAs from Arabidopsis. The Plant cell. 2004;16:2001–2019. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.022830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maunoury N, Vaucheret H. AGO1 and AGO2 act redundantly in miR408-mediated Plantacyanin regulation. PloS one. 2011;6:e28729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schwab R, et al. Specific effects of microRNAs on the plant transcriptome. Developmental cell. 2005;8:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feng H, et al. Target of tae-miR408, a chemocyanin-like protein gene (TaCLP1), plays positive roles in wheat response to high-salinity, heavy cupric stress and stripe rust. Plant molecular biology. 2013;83:433–443. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Engelsdorf T, et al. Reduced carbohydrate availability enhances the susceptibility of Arabidopsis toward Colletotrichum higginsianum. Plant physiology. 2013;162:225–238. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.209676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bonfig KB, et al. Post-translational derepression of invertase activity in source leaves via down-regulation of invertase inhibitor expression is part of the plant defense response. Molecular plant. 2010;3:1037–1048. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herbers K, Meuwly P, Frommer WB, Metraux JP, Sonnewald U. Systemic Acquired Resistance Mediated by the Ectopic Expression of Invertase: Possible Hexose Sensing in the Secretory Pathway. The Plant cell. 1996;8:793–803. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.5.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen LQ, et al. Sugar transporters for intercellular exchange and nutrition of pathogens. Nature. 2010;468:527–532. doi: 10.1038/nature09606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Komatsu K, et al. Group A PP2Cs evolved in land plants as key regulators of intrinsic desiccation tolerance. Nature communications. 2013;4:2219. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yao Y, et al. Cloning and characterization of microRNAs from wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Genome biology. 2007;8:R96. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.An J, Lai J, Sajjanhar A, Lehman ML, Nelson CC. miRPlant: an integrated tool for identification of plant miRNA from RNA sequencing data. BMC bioinformatics. 2014;15:275. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang X, Bennetzen JL. Current status and prospects for the study of Nicotiana genomics, genetics, and nicotine biosynthesis genes. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2015;290:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-0989-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meyers BC, et al. Criteria for Annotation of Plant MicroRNAs. The Plant cell. 2008;20:3186–3190. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dai X, Zhao PX. psRNATarget: a plant small RNA target analysis server. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39:W155–159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen C, et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Varkonyi-Gasic E, Wu R, Wood M, Walton EF, Hellens RP. Protocol: a highly sensitive RT-PCR method for detection and quantification of microRNAs. Plant methods. 2007;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nawrocki EP, et al. Rfam 12.0: updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic acids research. 2015;43:D130–137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.