Abstract

Context:

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a chronic debilitating disease which is often under reported, but laid significant impact on one's quality of life (QoL) thus is of public health importance.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to find out proportion of rural women have UI, its associated risk factors and treatment-seeking behavior, QoL of affected women.

Methods:

This was a cross-sectional clinic-based study conducted from October 2016 to January 2017 among 177 women aged 50 years or above attending a rural health facility with a structured schedule. Data were analyzed using appropriate statistical methods by SPSS (version 16).

Results:

Forty-nine (27.7%) out of 177 women were found having UI. The most prevalent type of UI was stress UI (51.0%), followed by mixed UI (32.7%) and urge UI (16.3%). In bivariate analysis, study participants who were illiterate, having a history of prolonged labor, having a history of gynecological operation, normal vaginal deliveries (NVDs) (>3), diabetic, having chronic cough, having constipation, and having lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) had shown significantly greater odds of having UI. In multivariable illiteracy (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] - 2.41 [1.02–5.69]), NVDs (AOR - 3.37 [1.54–7.37]), a history of gynecological operation (AOR - 3.84 [1.16–12.66]), chronic cough (AOR - 2.69 [1.21–5.99]), LUTS (AOR - 2.63 [1.15–6.00]) remained significant adjusted with other significant variable in bivariate analysis. Those with mixed UI had 5.33 times higher odds having unfavorable QoL. Only 30.6% sought medical help. Treatment-seeking behavior shown negative correlation with QoL while fecal incontinence and LUTS shown possitive correlation.

Conclusions:

The study revealed that rural women are indeed at high risk of developing UI. Majority of them did not sought treatment for UI which is matter of concern. Generating awareness regarding UI may help to improve health-seeking behavior and QoL.

KEYWORDS: International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-urinary incontinence, lower urinary tract symptoms, quality of life, urinary incontinence

INTRODUCTION

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a common but often under reported medical condition laid significant impact in ones quality of life (QoL). The International Continence Society defined UI as “the complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine and which is a social or hygienic problem.”[1]

UI is estimated to affect 200 million people worldwide and it will likely to affect over 423 million people by 2018.[2,3] The prevalence of UI increases with age. Moderate to severe UI affects 7% of women 20–39 years of age, 17% 40–59 years of age, 23% 60–79 years of age, and 32% ≥80 years of age.[3] This number may be an underestimate because majority of women fail to report UI to their health-care providers.[4]

Potential risk factors for UI include increasing age, parity, vaginal deliveries, obesity, surgery, constipation, and chronic respiratory problems such as cough.[5]

The inability to control urine is quite an unpleasant and distressing problem. Although it does not lead to death, it causes substantial morbidity, social seclusion, and psychological stress resulting in impaired QoL. Many women are too embarrassed to talk about it and some believe it to be untreatable.[6]

Most studies on this topic have been carried out in developed countries and affluent study populations. Scarce data exist on its prevalence in India, in rural women, or in those of lower socioeconomic status. The condition is usually under reported as many women hesitate to seek help or report symptoms to medical practitioners due to the embarrassing and culturally sensitive nature of this condition. An updated picture of UI in rural women will be of great importance in helping formulating strategies of prevention and control for UI and furthermore in reducing disease burden in India and will provide valuable and useful experiences and suggestions for other Asian countries and even for the world. This study examined UI in rural women, associated risk factors, treatment-seeking behavior, and QoL of affected women.

METHODOLOGY

It was a clinic-based observational study and cross-sectional in design. The study was conducted in Anandanagar Primary Health Centre's (PHC) Outpatient Department (OPD) during the months of October 2016 to January 2017. Women aged 50 years or above attending OPD of Anandanagar PHC were approached those who gave informed consent were included while chronically ill patients were excluded. Census method of sampling was followed. One hundred and ninety-five women aged 50 years of above attending OPD of Anandanagar PHC were approached 18 did not agreed to participate so were excluded. Structured schedule based on demographic, various risk factors of UI, the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ)-UI,[7] four questions adopted from I-QoL,[8] weighing machine, and measuring tape was used for data collection. ICIQ-UI was used to screen and classify UI. ICIQ-UI and four questions adopted from I-QoL were used to assess QoL. Pretesting of the questionnaire was done among thirty women aged 50 years or above in adjacent Diara PHC. Cronbach's alpha of QoL questionnaire was 0.798. Based on the results of pretesting, necessary modifications were made and final questionnaire was prepared. Two days in a week and 2–3 h a day was allotted for data collection interviewing a woman at an average took 10–15 min. On this way, 177 women were interviewed in 3 months period. The maximum and minimum attainable QoL score was 26 and 0, respectively, while maximum and minimum attained QoL score were 20 and 4, respectively. QoL worsens with higher QoL score. Operational definitions used are listed next.

Socioeconomic status was assessed by modified B. G. Prasad scale 2016.[9]

Heavy work: those reported their occupation as cultivator was considered doing heavy work.

Exposed to tobacco: those addicted to tobacco smoking, tobacco chewing, or exposed to passive smoking considered to be exposed to tobacco.

UI: those who reported at least one episode of involuntary loss of urine in last 1 week were considered having UI.

Fecal incontinence: those who reported at least one episode of involuntary loss of stool in last 1 week were considered having fecal incontinence.

Chronic cough: if cough was present for more than 3 days/week for the past 3 months or more, then it was considered as chronic cough.

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS): participants having anyone of the following symptoms were considered having LUTS: lower abdominal pain, burning micturition, nocturia, hematuria/urethral discharge, urgency, incomplete voiding, and frequent micturition.

Unfavorable QoL: those had QoL score ≥13 (median) were considered having unfavorable QoL.

Ethical issues

Informed verbal consent of the study participants was taken before conducting the study. During data collection, their confidentialities were maintained.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 16 (SPSS 16). First, a bivariate analysis was done to ascertain the relationship between socioeconomic, demographic, and certain known risk factors variables with UI. Only those who found to be significant were entered into a multiple logistic model by forced entry method. The strength of associations was assessed by odds ratio (OR) at 95% confidence interval, statistical significance for all analyses was set at P < 0.05. Spearman rho correlation between various factors and QoL score was done to know their strength of correlation.

RESULTS

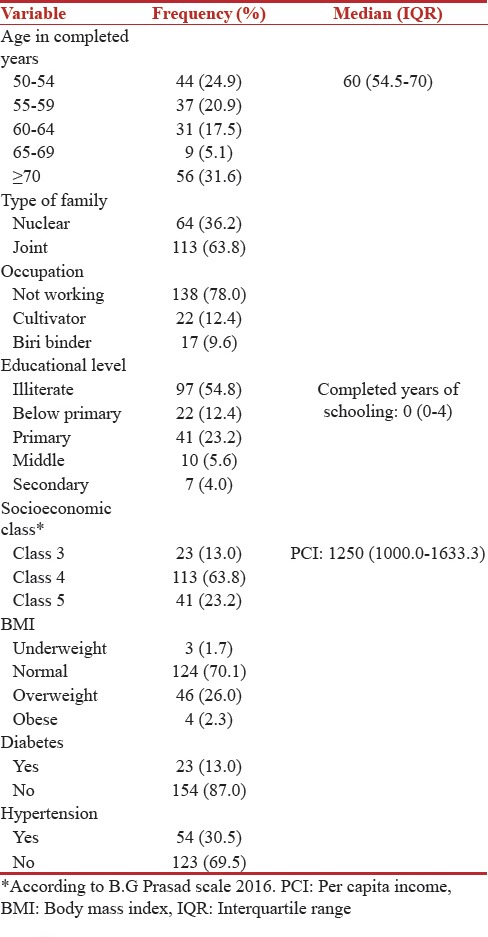

Most of the study participants belonged to age group 70 years or above. The mean (standard deviation) of the age of the study participants was 61.91 (9.69). Nearly 13% of them were diabetic while 30.5% of them were hypertensive [Table 1].

Table 1.

Background characteristics of the study participants (n=177)

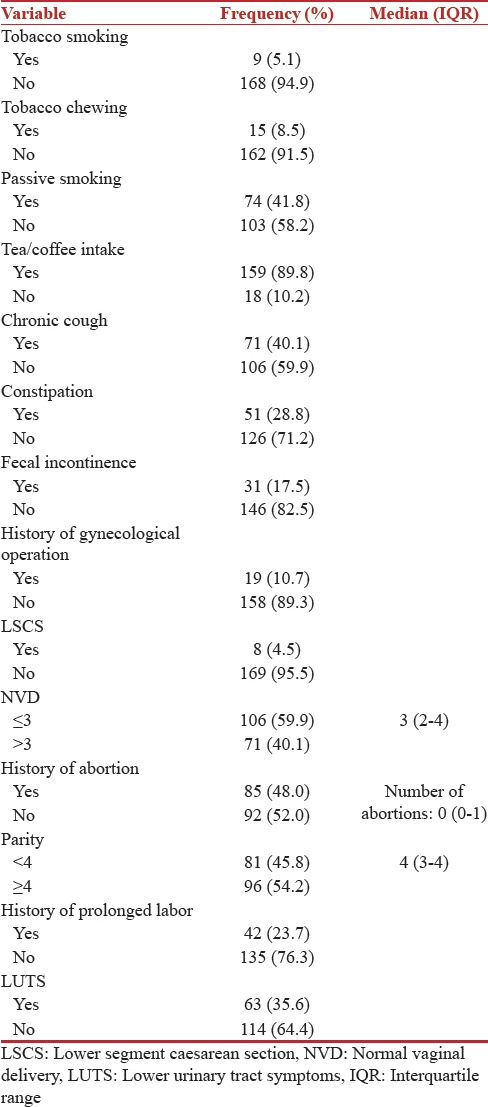

Nearly 10.7% of them had a history of gynecological operation. Thirteen of them had a history of hysterectomy while six had undergone operation for prolapse. Majority of them had normal vaginal delivery (NVD) 91.5% while 48.0% and 23.7% had a history of abortion and prolonged labor, respectively. About 35.6% of them were suffering from and one of the LUTSs [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution of study participants according to some known risk factors of urinary incontinence (n=177)

Forty-nine (27.7%) out of 177 women were found having UI. The most prevalent type of UI was stress UI (51.0%); followed by mixed UI (32.7%) and urge UI (16.3%). Only 42.9% shared their UI problems with anyone. Most of them shared their UI problem with husband (76.2%) and doctor (71.4%). Ten (47.6%) shared their problems with friend/neighbor while 8 (38.1%) (4 sisters, 3 daughters, and 1 daughter in law) shared their problems with other family members. Only 15 (30.6%) sought treatment for UI. The most prevalent cause of not seeking treatment was lack of money (70.5%) followed by shyness/embarrassment (55.8%). Sixteen (47.1%) of them considered it as normal status of aging while fear of hospitals prevented eight of them for seeking treatment. Nearly, 14.7% of them thought that UI is incurable.

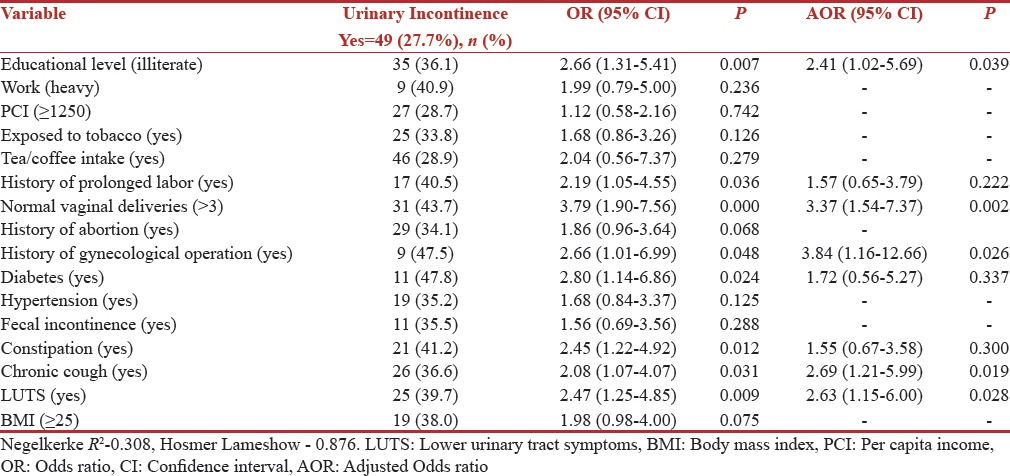

In bivariate logistic regression analysis, study participants, who were illiterate, having a history of prolonged labor, having a history of gynecological operation, NVDs (>3), diabetic, chronic cough, constipation, LUTS, had shown significantly greater odds of having UI. In multivariable model illiteracy (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] - 2.41 [1.02–5.69]), NVDs (AOR - 3.37 [1.54–7.37]), a history of gynecological operation (AOR - 3.84 [1.16–12.66]), chronic cough (AOR - 2.69 [1.21–5.99]), and LUTS (AOR - 2.63 [1.15–6.00]) remained significant adjusted with other significant variable in bivariate analysis [Table 3].

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression showing association of urinary incontinence with some known risk factors (n=177)

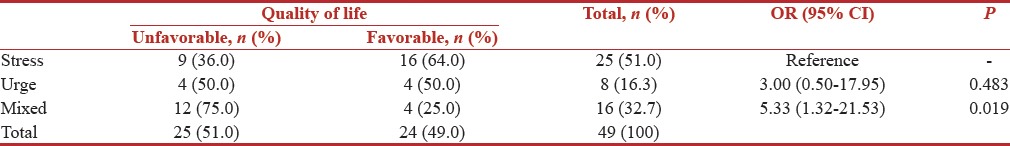

Table 4 had shown association between type of UI and QoL. Those with mixed UI had higher odds (OR - 5.33 [1.32–21.53]) of having unfavorable QoL compared to those with stress UI.

Table 4.

Association between type of urinary incontinence and quality of life (n=49)

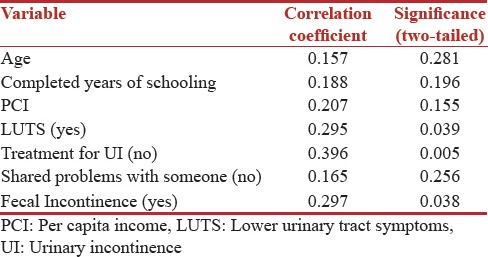

Among 49 incontinent women, those who had LUTS, fecal incontinence and did not seek medical help had positive correlation with QoL score [Table 5].

Table 5.

Spearman rho correlation of quality of life with various factors (n=49)

DISCUSSION

About 27.7% of the study population was found to have UI. The findings were consistent with findings of Prabhu and Shanbhag[10] (25.5%), Ansar et al.[11] (23.9%), and Seshan and Muliira[12] (33.8%), whereas Abha et al.[13] (34.0%), Kılıç[14] (37.2%), and Sensoy et al.[15] (44.6%) have reported more. Singh et al.[16] (21.8%), Ge et al.[17] (22.1%), Sumardi et al.[18] (13.0%), Abiola et al.[19] (12.6%), and Bodhare et al.[20] (10.0%) have reported less. This variance in the prevalence may be due to different study population, settings, and definition of UI used.

The study revealed that illiterate women are at more risk. Hence educational level plays a vital role in this regard. Sensoy et al.,[15] Seshan and Muliira,[12] and Ge et al.[17] had similar findings. A history of prolonged labor: it is an established cause of urinary tract injury thus increases the risk of UI. The study had identified a history of prolonged labor as a risk factor for UI similar to Bodhare et al.[20] and Kılıç[14] with increase in number of childbirth chance of trauma to the urinary tract also increases. The study established NVD as a risk factor for UI similar as Singh et al.,[16] Ge et al.,[17] Seshan and Muliira,[12] and Sensoy et al.[15]

A history of gynecological operation imposes risk of iatrogenic trauma to the urinary tract, thus increasing risk of UI. The study revealed that also which is similar to findings of Prabhu and Shanbhag,[10] Sensoy et al.,[15] Ge et al.,[17] and Singh et al.[16] Diabetes causes polyuria which laid additional burden on sphincters of urinary tract resulting in UI. The current study also establishes the fact same as Prabhu and Shanbhag,[10] Kılıç,[14] Ge et al.,[17] and Singh et al.[16] Constipation and chronic cough create additional stress on both the anal and urethral sphincter resulting into UI. The studies by Prabhu and Shanbhag,[10] Bodhare et al.,[20] and Sensoy et al.[15] identified constipation and chronic cough both as risk factors of UI while Ge et al.[17] found constipation and Sumardi et al.[18] identified chronic cough as a risk factor. The study establishes LUTS as one of the most important risk factors for UI similar to Sumardi et al.,[18] Sensoy et al.,[15] Ge et al.,[17] and Kılıç.[14]

The most prevalent type of UI was stress UI (51.0%), followed by mixed UI (32.7%) and urge UI (16.3%). This finding further corroborated earlier reports from epidemiological studies of UI in India in which stress incontinence was the most common type of UI among women with UI.[10,13,16]

Those with mixed UI had poorer QoL compared other UI. The study conducted by Frick et al.,[21] Minassian et al.[22] and Mallah et al.[23] had similar findings.

Only 30.6% sought treatment for UI which is better compared to Prabhu and Shanbhag[10] (14.4%), Sarici et al.[24] (10.7%), Jokhio et al.[25] (15.7%) and worse compared to Lasserre et al.[26] (39.7%). Among incontinent, those who did not seek treatment for UI had poorer QoL as not seeking treatment had positive correlation with QoL score. The findings were similar with Sarici et al.[24] The current study highlighted a lack of money and embarrassment as predominant cause of not seeking medical treatment. A qualitative study by Vethanayagam et al.[27] has found out physicians lack of prioritization and embarrassment as a leading cause. In our study, among incontinent women, those who had LUTS and fecal incontinence had unfavorable QoL as both had positive correlation with QoL score. The study conducted by Arslantas et al.[28] reported that LUTS is inversely correlated with the QoL. Kupelian et al.[29] reported similar findings. A case–control study conducted by de Mello Portella et al.[30] reported that UI group had higher prevalence of fecal incontinence than the other groups and anal incontinence adversely affected the QoL. The study by Markland et al.[31] reported findings concurrent to our findings.

Strengths

It was one of the fewer studies in rural settings of a developing country like India where data relating to UI are scarce. Taking into consideration cultural sensitivity and embarrassment associated with UI, an OPD-based study in this topic is more feasible alternative than community-based in which maintenance of privacy during data collection is difficult.

Limitations

The sample size was small. All the data were self-reported by study participants. Data were not cross-verified. Thus, there may be over or under reporting. Definitive testing was not done to measure UI.

CONCLUSIONS

Prevalence of UI is high in rural women. Most prevalent one is stress UI. Majority of them did not sought treatment for UI which is matter of concern. Generating awareness regarding UI may help to improve health-seeking behavior. In the current study, UI is predicted by certain modifiable risk factors, proper management of which is warranted to reduce the burden of UI and thus improving QoL. Several treatment choices for UI are now available with greater effectiveness and feasibility. For example, pelvic floor muscle training is established to be effective first-line intervention for improving urinary symptoms as well as QoL as evidenced in some of the studies.[32,33,34] Thus, encouraging pelvic floor muscle training in at risk women and those who are affected is useful in both the prevention and management of UI. An attempt should be made by doctor or health personnel to screen at risk women for UI at every given opportunity by asking leading questions so that the affected can be timely referred for relevant management.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrams P, Andersson KE, Birder L, Brubaker L, Cardozo L, Chapple C, et al. Fourth international consultation on incontinence recommendations of the international scientific committee: Evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:213–40. doi: 10.1002/nau.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300:1311–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norton P, Brubaker L. Urinary incontinence in women. Lancet. 2006;367:57–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67925-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Limpawattana P, Kongbunkiat K, Sawanyawisuth K, Sribenjalux W. Help-seeking behaviour for urinary incontinence: Experience from a university community. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 24];Int J Urol Nurs. 2015 9:143–8. Available from: http://www.doi.wiley.com/10.1111/ijun.12065 . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaivas GJ. Urinary incontinence: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, evaluation, and management overview. Campbell's Urol. 2002;2:1207–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newman DK. Stress Urinary Incontinence in Women: Involuntary urine leakage during physical exertion affects countless women. Am J Nurs. 2003;103:46–55. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200308000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P, et al. ICIQ: A brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:322–30. doi: 10.1002/nau.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patrick DL, Martin ML, Bushnell DM, Yalcin I, Wagner TH, Buesching DP, et al. Quality of life of women with urinary incontinence: Further development of the incontinence quality of life instrument (I-QOL) Urology. 1999;53:71–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasudevan J, Mishra AK, Singh Z. An update on B. G. Prasad's socioeconomic scale: May 2016. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 25];Int J Res Med Sci. 2016 44:4183–6. Available from: http://www.msjonline.org . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prabhu SA, Shanbhag SS. Prevalence and risk factors of urinary incontinence in women residing in a tribal area in Maharashtra, India. J Res Health Sci. 2013;13:125–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ansar H, Adil F, Munir AA. Unreported urinary and anal incontinence in women. J Liaquat Univ Med Health Sci. 2005;4:54–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seshan V, Muliira JK. Self-reported urinary incontinence and factors associated with symptom severity in community dwelling adult women: Implications for women's health promotion. BMC Womens Health. 2013;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abha S, Priti A, Nanakram S. Incidence and epidemiology of urinary incontinence in women. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2007;57:155–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kılıç M. Incidence and risk factors of urinary incontinence in women visiting family health centers. Springerplus. 2016;5:1331. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2965-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sensoy N, Dogan N, Ozek B, Karaaslan L. Urinary incontinence in women: Prevalence rates, risk factors and impact on quality of life. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29:818–22. doi: 10.12669/pjms.293.3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh U, Agarwal P, Verma ML, Dalela D, Singh N, Shankhwar P, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of urinary incontinence in Indian women: A hospital-based survey. Indian J Urol. 2013;29:31–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.109981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ge J, Yang P, Zhang Y, Li X, Wang Q, Lu Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of urinary incontinence in Chinese women: A population-based study. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27:NP1118–31. doi: 10.1177/1010539511429370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sumardi R, Mochtar CA, Junizaf, Santoso BI, Setiati S, Nuhonni SA, et al. Prevalence of urinary incontinence, risk factors and its impact: Multivariate analysis from indonesian nationwide survey. Acta Med Indones. 2014;46:175–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abiola OO, Idowu A, Ogunlaja OA, Williams-Abiola OT, Ayeni SC. Prevalence, quality of life assessment of urinary incontinence using a validated tool (ICIQ-UI SF) and bothersomeness of symptoms among rural community: Dwelling women in Southwest. Nigeria. 2016;3:989–97. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodhare TN, Valsangkar S, Bele SD. An epidemiological study of urinary incontinence and its impact on quality of life among women aged 35 years and above in a rural area. Indian J Urol. 2010;26:353–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.70566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frick AC, Huang AJ, Van den Eeden SK, Knight SK, Creasman JM, Yang J, et al. Mixed urinary incontinence: Greater impact on quality of life. J Urol. 2009;182:596–600. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minassian VA, Devore E, Hagan K, Grodstein F. Severity of urinary incontinence and effect on quality of life in women by incontinence type. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:1083–90. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31828ca761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallah F, Montazeri A, Ghanbari Z, Tavoli A, Haghollahi F, Aziminekoo E, et al. Effect of urinary incontinence on quality of life among Iranian women. J Family Reprod Health. 2014;8:13–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarici H, Ozgur BC, Telli O, Doluoglu OG, Eroglu M, Bozkurt S, et al. The prevalence of overactive bladder syndrome and urinary incontinence in a Turkish women population; associated risk factors and effect on quality of life. Urologia. 2016;83:93–8. doi: 10.5301/uro.5000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jokhio AH, Rizvi RM, Rizvi J, Macarthur C. Urinary incontinence in women in rural Pakistan: Prevalence, severity, associated factors and impact on life. BJOG. 2013;120:180–6. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lasserre A, Pelat C, Guéroult V, Hanslik T, Chartier-Kastler E, Blanchon T, et al. Urinary incontinence in French women: Prevalence, risk factors, and impact on quality of life. Eur Urol. 2009;56:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vethanayagam N, Orrell A, Dahlberg L, McKee KJ, Orme S, Parker SG, et al. Understanding help-seeking in older people with urinary incontinence: An interview study. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:1061–069. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arslantas D, Gokler ME, Unsal A, Başeskioğlu B. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms among individuals aged 50 sYears and over and its effect on the quality of life in a semi-rural area of Western Turkey. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2017;9:5–9. doi: 10.1111/luts.12100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kupelian V, Wei JT, O'Leary MP, Kusek JW, Litman HJ, Link CL, et al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and effect on quality of life in a racially and ethnically diverse random sample: The boston area community health (BACH) survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2381–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Mello Portella P, Feldner PC, Jr, da Conceição JC, Castro RA, Sartori MG, Girão MJ, et al. Prevalence of and quality of life related to anal incontinence in women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;160:228–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markland AD, Richter HE, Kenton KS, Wai C, Nager CW, Kraus SR, et al. Associated factors and the impact of fecal incontinence in women with urge urinary incontinence: From the urinary incontinence treatment network's behavior enhances drug reduction of incontinence study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:424.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan HL, Chan SS, Law TS, Cheung RY, Chung TK. Pelvic floor muscle training improves quality of life of women with urinary incontinence: A prospective study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53:298–304. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kashanian M, Ali SS, Nazemi M, Bahasadri S. Evaluation of the effect of pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT or kegel exercise) and assisted pelvic floor muscle training (APFMT) by a resistance device (Kegelmaster device) on the urinary incontinence in women: A randomized trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;159:218–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jurczak I, Chrzęszczyk M. The impact assessment of pelvic floor exercises to reduce symptoms and quality of life of women with stress urinary incontinence. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2016;40:168–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]