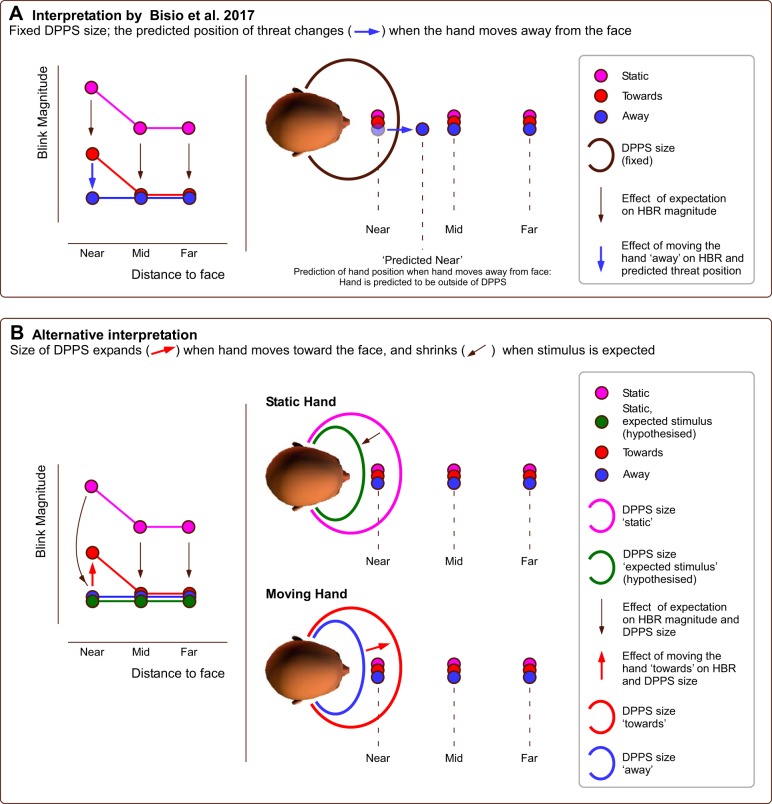

Fig. 1.

Schematic of hand movement effects on hand-blink reflex (HBR) magnitude. A: in the interpretation put forward by Bisio et al. (2017) the size of the defensive peripersonal space (DPPS) is fixed. Left: sketch of HBR magnitude across different conditions. Right: assumed DPPS (black line) and predicted positions of the threat (colored circles). In this interpretation, when 1) the threat is near the face and 2) it moves away from the face, the position of the threat is predicted to shift outside the DPPS (blue arrow in right subpanel), with a consequent decrease in HBR magnitude at the near position (blue arrow in left subpanel). In both conditions where the hand moves, the movement of the hand is linked to the stimulus onset, therefore causing an overall HBR magnitude decrease. Importantly, Bisio et al. assume this “expectation effect” to be equal at all hand positions (black arrows in left subpanel). B: an alternative interpretation is that the DPPS size is malleable. Left: sketch of HBR magnitudes across different conditions, also including hypothetical true baseline magnitude when the eliciting shock is expected. Right: implied size of DPPS (colored lines) and predicted positions of the threat (colored circles). In this alternative interpretation, when the threat moves toward the face, the DPPS expands (red arrow in right subpanel), causing an increase in HBR magnitude at the near position (red arrow in left subpanel). In this interpretation, the expectation effect results in both an overall HBR magnitude decrease and in a DPPS shrinkage (black arrows in both subpanels). While both interpretations are plausible, only the alternative interpretation fits with prior empirical observations (e.g., Wallwork et al. 2016).