Abstract

Methods are described for the determination of pKas for weak carbon acids in water. The application of these methods to the determination of the pKas for a variety of carbon acids including nitriles, imidazolium cations, amino acids, peptides and their derivatives and, α-iminium cations is presented. The substituent effects on the acidity of these different classes of carbon acids are discussed; and, the relevance of these results to catalysis of the deprotonation of amino acids by enzymes and by pyridoxal 5′-phosphate is reviewed. The procedure for estimating the pKa of uridine 5′-phosphate for C-6 deprotonation at the active site of orotidine 5′-phosphate decarboxylase is described, and the effect of a 5-F substituent on carbon acidity of the enzyme-bound substrate is discussed.

Keywords: Proton Transfer, Carbon Acids, Imidazole Carbenes, Enolates, Pyridoxal, Enzyme, Catalysis

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

I was taught by my PhD advisor Perry Frey that the greater carbon acidity of thioesters compared to esters strongly favors enzymatic catalysis of Claisen-type condensation reactions of thioesters (Scheme 1),1 and the evolution of metabolic pathways which feature this high-energy functional group in the biosynthesis of carbon-carbon bonds. I was surprised to then learn from my postdoctoral advisor Bill Jencks how little was known about the stability of thioester enolates in water. An attempt to generate and detect a thioester enolate by hydroxide-ion catalyzed deprotonation of the α–carbonyl carbon of ethyl thioacetate in tritium-labeled water met with scant success, because deprotonation of this carbon acid is much slower than competing thioester hydrolysis to form the carboxylic acid.2 Thioester enolates were likewise considered as putative intermediates of enzyme-catalyzed Claisen condensation,3 but there was no direct documentation of their existence at enzyme active sites.4

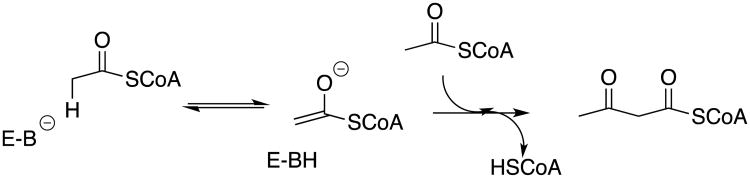

Scheme 1.

Thiolase-catalyzed Claisen condensation reaction of acetyl coenzyme A to form acetoacetyl coenzyme A.

Our early work focused on characterizing the effect of electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents on carbocation stability in water.5 During this time I came to appreciate how little was known about the acidity of simple carboxylic acid derivatives in water. Not only was the pKa of ethyl thioacetate not known, but the following widely cited, poorly documented, pKas from work by Pearson and Dillon published in 1953 appeared to be regarded as adequate: ethyl acetate; pKa = 24.5; acetonitrile; pKa = 25; and, acetamide; pKa = 25.6 It seemed unlikely to us that these different carbon acids would have similar pKas, and we became intrigued by the problem of developing new methods to document the pKas of weak carbon acids in water.

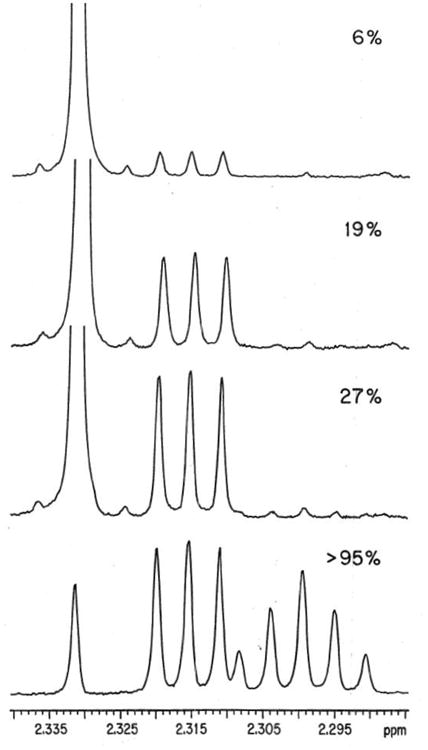

2 The Carbon Acidity of Ethyl Thioacetate

We first examined the carbon acidity of the simple thioester ethyl thioacetate. The challenges here were to modernize the analytical methods used to follow the transfer of hydrons from solvent to the carbon acid through a thioester enolate intermediate, and to minimize the thioester hydrolysis reaction. We avoided experiments to monitor the exchange of tritium from the solvent water into carbon acids, because of difficulties in separating tritiated solvent from volatile tritiated carbon acids, such as ethyl thioacetate or ethyl acetate. We focused instead on monitoring buffer and solvent-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions in D2O, and observed that buffer-catalyzed exchange of deuterium between D2O and the acidic α-CH3 of ethyl thioacetate is easily detected using 500 MHz 1H-NMR. This is illustrated by Figure 1, which shows that the signals for α-CH2D and α-CHD2 labeled thioesters are cleanly resolved from one another and the signal for the starting α-CH3 group (Scheme 2).7

Figure 1.

Partial 500-MHz 1H NMR spectra (recorded in CDCl3) of ethyl thioacetate recovered at different times during an experiment to monitor the exchange of the α-protons for deuterium in the presence of 3-quinuclidinone buffers in D2O.7 The fraction of exchanged thioester is indicated at the top right of each spectrum. At early times, the singlet at 2.331 ppm due to the α-CH3 group is replaced by an upfield triplet at 2.315 ppm (J = 2.2 Hz) for the α-CH2D group and at later times this is replaced by a quintet at 2.299 ppm (J = 2.2 Hz) for the α-CHD2 group. The tiny peaks on either side of the major singlet at 2.331 ppm in the top three spectra are 13C-satellites from coupling of the α-CH3 hydrogens to the neighboring carbonyl carbon. Reprinted with permission from ref. 6. Copyright 1992 American Chemical Society.

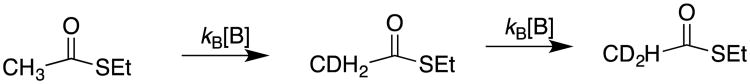

Scheme 2.

Base-catalyzed exchange for deuterium in D2O of the α-CH3 hydrogens of ethyl thioacetate.

Using simple rules of organic reactivity taught to us by Bill Jencks, we examined the reaction of ethyl thioacetate at neutral pH and in the presence of quinuclidine buffers (Scheme 3).8 These buffers provide strong catalysis of deprotonation of α-carbonyl carbon,9 but are less effective at promoting hydrolysis.10 Deuterium exchange was predicted to become the dominant reaction at neutral pH where [kB[B] > (k′LO [LO-] + k′B[B])], Scheme 3). This prediction was confirmed in the experiment illustrated by Figure 1, where > 95% exchange of the fully hydrogen labeled ethyl thioacetate was observed with little thioester hydrolysis.7

Scheme 3.

Pathways for lyoxide ion- and buffer-catalyzed deprotonation and hydrolysis reactions of ethyl thioacetate. The proton transfer reaction is favored for catalysis by 3-substituted quinuclidines (kB ≫ k′B) and the hydrolysis reaction is favored for catalysis by lyoxide ion (k′HO > kHO).

A comparison between the kinetic acidity for deprotonation of ethyl thioacetate (kB = 2.2 × 10-5 M-1s-1) and acetone (pKa = 19, kB = 5.2 × 10-5 M-1s-1) by quinuclidinone buffer in water at 25 °C,11 gave a range of 20.4 ≤ pKa ≤ 21.5 for the former carbon acid.7 These data demonstrate that the thioester enolate is sufficiently stable to exist for the time of a bond vibration, and is a viable reaction intermediate for enzyme-catalyzed Claisen condensation reactions.4, 7

3 The Carbon Acidity of Carboxylic Acid Derivatives

Following up on our demonstration that 500 MHz 1H-NMR is a powerful analytical tool for monitoring deuterium exchange reactions between solvent DOD and carbon acids,7 we used this method to probe the carbon acidity of a broad range of carboxylic acid derivatives. The critical experiment is the determination of rate constants kB or kLO (M-1s-1) for buffer or lyoxide ion-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions by rate-determining formation of unstable carbanion intermediates.12-14

The next step was the analyses of structure-reactivity relationships for reversible proton transfer at these weak carbon acids, which show that carbanion protonation in the strongly thermodynamically favorable direction to regenerate the carbon acid may serve as “clocks” for carbanion lifetime in the calculations of carbon acid pKas.13-16 This procedure is summarized in Scheme 4 for the calculation of carbon acid pKas from: (a) The pKa of the buffer acid catalyst of carbon protonation, the rate constant kB for deprotonation of the carbon acid by the Brønsted base, and kBH = kd = 5 × 109 M-1 s-1 for diffusion limited carbanion protonation in the microscopic reverse direction.12 (b) The pKa of water, the rate constant kHO for deprotonation of the carbon acid by hydroxide anion, and kHOH = 1 × 1011 s-1 for carbanion protonation that is limited by the rate of water rotation into a reactive position within the first-formed solvent shell.13, 14, 17 The rationale for the development of these clocks is described in greater detail in our original publications and subsequent review articles.13-16, 18

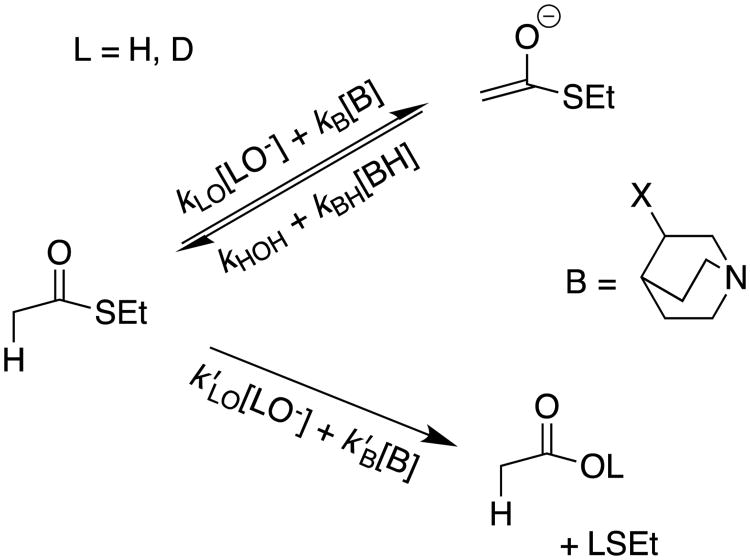

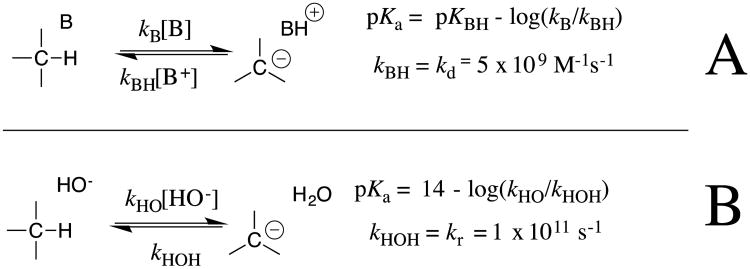

Scheme 4.

Equations used to calculate pKas for weakly acidic carbon acids from experimentally determined rate constants kB or kLO (M-1s-1) for buffer or lyoxide ion-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions, when protonation of the carbanion by buffer acid or solvent serves as a clock for carbanion lifetime. (A) Diffusion limited protonation of the carbanion by buffer acids, with an estimated rate constant of kBH = kd = 5 × 109 M-1 s-1.12 (B) Carbanion protonation by water in a reaction limited by reorganization of the solvent shell, which places water into a reactive conformation; kHOH = kr = 1 × 1011 s-1.13, 14

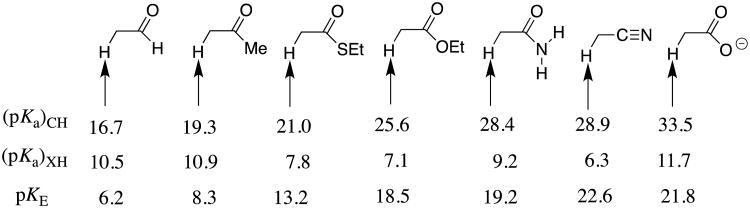

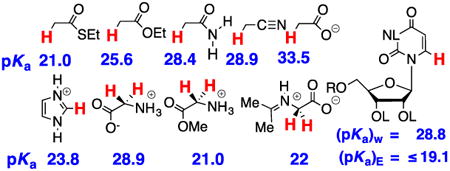

These experimental results provide the following equilibrium constants (chart 1) as defined in Schemes 5A and 5B, for the enolization and carbon-deprotonation of carboxylic acids derivatives.7, 12-14 (a) The carbon acid pKas [(pKa)CH] for deprotonation of the α-carbonyl carbon.7, 12-14 (b) The heteroatom pKas for deprotonation of the corresponding enol tautomers [(pKa)XH].7, 12-14, 19 (c) The values of pKE = -log KE for conversion of the carbonyl derivative to the enol tautomer, which were calculated from the relationship pKE = (pKa)CH - [(pKa)XH].19 chart 1 also reports the values of equilibrium constants determined by Kresge and coworkers for enolization of acetaldehyde and acetone.19

Chart 1.

Logarithmic values of the equilibrium constants (Scheme 5) for reactions of carboxylic acid derivatives, an aldehyde, a ketone and a nitrile.

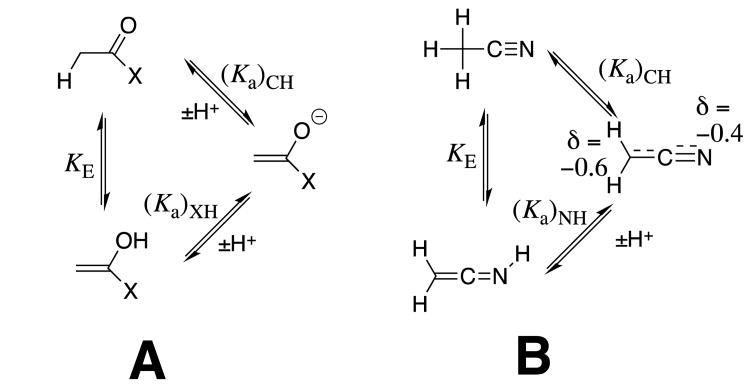

Scheme 5.

Thermodynamic cycles which divide tautomerization of carboxylic acid derivatives (KE) into separate steps for proton transfer at carbon [(Ka)CH] and at a heteroatom [1/(Ka)XH]. (A) Enolization at α–carbonyl carbon. (B) Tautomerization of acetonitrile.

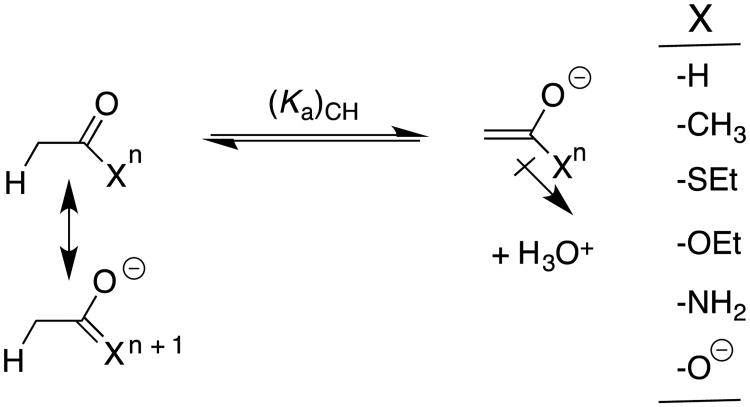

Substituent Effects on Carbon Acid pKa: Deprotonation of α–Carbonyl Carbon

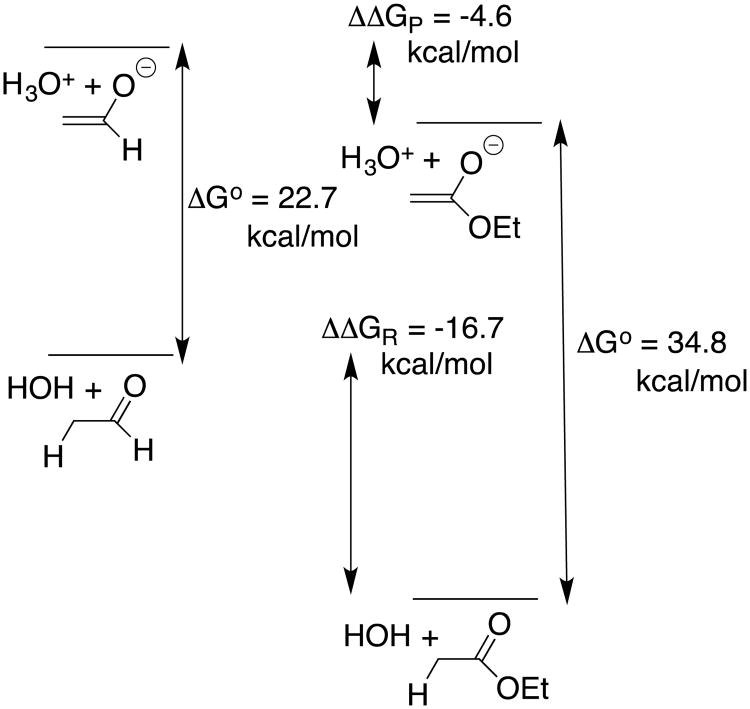

The substituent effects on the equilibrium constants for formation of reactive intermediates, such as carbanions and carbocations, are most often controlled by interactions between the substituent and the charged intermediate.5, 16 The data from chart 1 provide an instructive example of a case where the substituent effects on carbon acidity [(pKa)CH] are controlled instead by interactions between the neutral resonance electron-donating substituents and α–carbonyl group (Scheme 6). This is illustrated by Figure 2 for the EtO-substituted carbonyl group (an ester), where the total effect of the -OEt substituent on ΔG° for deprotonation of acetaldehyde (ΔΔG° = 34.8 - 22.7 = 12.1 kcal/mol) is partitioned into interactions that affect the stability of the reactant (ΔΔGR) and of the product (ΔΔGP). In this case, the effect of stabilizing polar interactions between the electron-withdrawing –OEt and the enolate oxyanion, ΔΔGP = -4.6 kcal/mol (Scheme 6) is obtained as the effect of–OEt on ΔG° for deprotonation of the enolate [(Ka)XH]. The change in the stabilizing resonance interaction at the reactant, ΔΔGR = -16.7 kcal/mol (Scheme 6) is then calculated as the difference between the overall substituent effect on ΔG° (ΔΔG° = 12.1 kcal/mol) and the 4.6 kcal/mol substituent effect on product stability (eq 1). This value of ΔΔGR = -16.7 kcal/mol can also be obtained from the substituent effect on pKE (chart 1).

Scheme 6.

Illustration of the stabilizing resonance interaction between a substituent -X and the reactant carbonyl group, and of the stabilizing inductive interaction between electron-withdrawing–X and the enolate oxygen anion. The resonance and inductive substituent effects are assumed to dominate in determining the changes in pKE for enolization and in (pKa)XH for ionization at oxygen, respectively; and, to be negligible for acetaldehyde (X = H). Negligible polar effects on (pKE) and resonance effects on (pKa)XH are assumed for this analysis.

Figure 2.

Partitioning the overall effect of the –OEt group on the pKa of acetaldehyde (ΔΔG° = 34.8 – 22.7 = 12.1 kcal/mol) into product (ΔΔGP = -4.6 kcal/mol) and reactant effects (ΔΔGR = -16.7 kcal/mol). Negligible polar effects on (pKE) and resonance effects on (pKa)XH are assumed for this analysis.

| (1) |

Table 1 summarizes the interactions between substituents –X at the carbon acid reactant and the enol product, that were calculated from thermodynamic data reported in chart 1.14 These estimates reinforce and further define well-established trends.20 The most striking observation is that the resonance interaction of –OEt (-16.7 kcal/mol) and of –NH2 (-17.7 kcal/mol) with the carbonyl are similar to one another, and nearly as large as the -20.2 kcal/mol interaction for–O-. This shows that the energetic penalty to the separation of positive and negative charge at zwitterionic resonance structures for ethyl actetate and acetamide (Scheme 6) is small [(2-4)-kcal/mol] in comparison to the 20 kcal/mol stabilization obtained from delocalization of the unit negative charge at the acetate anion.

Table 1.

Interaction Energies Between–X and the Carbonyl Group at the Reacting Carboxylic Acid Derivative (ΔΔGR) or the Product Oxygen Anion (ΔΔGP), Estimated from Data Presented in Chart 1 and as Illustrated in Figure 2 for the –OEt Group.

| Substituent | ΔΔG° b kcal/mol | ΔΔGPc kcal/mol | ΔΔGRd kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|

| -CH3 | 3.5 | 0.5 | -3.0 |

| -SEt | 5.8 | -3.7 | -9.5 |

| -OEt | 12.1 | -4.6 | -16.7 |

| -NH2 | 15.9 | -1.8 | -17.7 |

| -O- | 22.8 | 2.6 | -20.2 |

The values of (ΔΔGR) and (ΔΔGP) are calculated from the substituent effects on (pKE) and (pKa)XH, respectively (Chart 1), using a factor of 1.36 to convert ΔpK to ΔΔG°.

The substituent effect on the free energy for ionization of acetaldehyde to form the enolate, calculated from the values of (pKa)CH reported in Chart 1.

The estimated polar interaction between the substituent and the oxygen anion at the enolate, calculated from the substituent effect on (pKa)OH for the enolate of acetaldehyde (Chart 1).

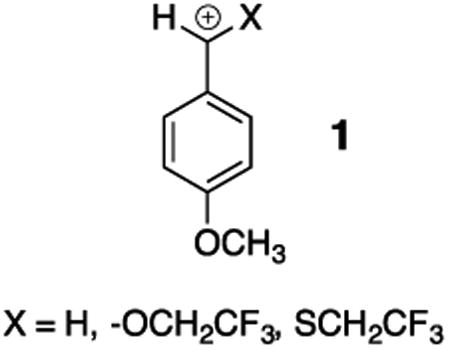

The 9.5 kcal/mol stabilizing interaction between –SEt and the carbonyl group is 60% that for –OEt (Table 1). This reflects the stronger overlap between the matching 2p-O and 2p-C orbitals at CH3C(O)OEt compared with the mismatched 3p-S and 2p-C orbitals at CH3C(O)SEt. By contrast, the similar stabilizing interactions of α–OCH2CF3 and α–SCH2CF3with the 4-methoxybenzyl carbocation 1 shows that these substituent effects are not controlled only by this difference in 2p and 3p orbital overlap.21 Pi-overlap between carbon and α–S compared with α–O appears to be favored when stabilization of positive charge at the more polarizable sulfur compared with oxygen becomes an important consideration.5

Carbon Acidity of Nitriles

The larger dipole moment for acetonitrile (3.2 D) compared with acetaldehyde (2.5 D) shows that–CN is more polar electron-withdrawing than –CHO. The greater resonance effect of -CHO dominates in determining the large difference in the pKas for acetonitrile (28.9) and acetaldehyde (16.7). By contrast, the pKas for dicyanomethane (11.4)22 and acetylacetone (8.9)23 are similar. This shows that the nearly additive effects of two strongly polar electron-withdrawing–CN groups balance the nonadditive resonance effects for the –CHO groups. This non-additivity of resonance effects has been referred to as “resonance saturation”.24

The results of high-level ab initio calculations provide the following insight critical to understanding the origin of the weaker resonance stabilization of the ketenimine anion formed by deprotonation of acetonitrile, compared with the enolate of acetaldehyde.13

A comparison of the calculated Hirshfeld atomic charges at acetonitrile and the α-cyano carbanion show that deprotonation of the carbon acid results in only a 0.4 unit increase in negative charge at the cyano group, and that the preponderance of negative charge (0.6 units, Scheme 5B) lies at the α–carbon for the carbanion, despite the smaller electronegativity of carbon compared with nitrogen.25

High-level ab initio calculations gave a value KE = 10-22.6 for tautomerization of acetonitrile to form the ketenimine (Scheme 5B),13 which is ca 16 orders of magnitude smaller than KE = 10-6.2 for tautomerization of acetaldehyde. The large barrier to tautomerization of acetonitrile to form the ketenimine is manifested as a high resistance to charge delocalization at the carbanion, which requires a large contribution of the unstable contributing cumulated valence bond resonance structure, to the overall structure. The result is a relatively large charge density at weakly electronegative carbon, and a low charge density at the nominally more electronegative nitrogen of the cyanomethyl carbanion (Scheme 5B).

4 The Carbon Acidity of Imidazolium Cations

I learned from Steven Diver, my colleague at Buffalo, of some of the many applications of electron-rich N-heterocyclic carbenes as ligands for organometallic catalysts,26, 27 and as nucleophilic catalysts of reactions such as benzoin condensation,28 and acyl transfer.29 We noted that, despite the reports of the isolation and characterization of stable N-heterocyclic and other diamino carbenes,27, 30 there were no systematic studies of the formation and stability of imidazoly-2-yl carbenes in water at room temperature, which would serve as the starting point for analyses of the kinetic and thermodynamic acidity of the C(2)-proton of simple imidazolium cations.

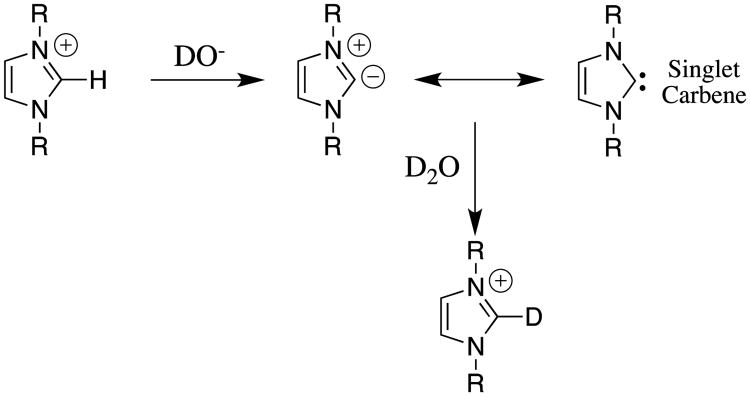

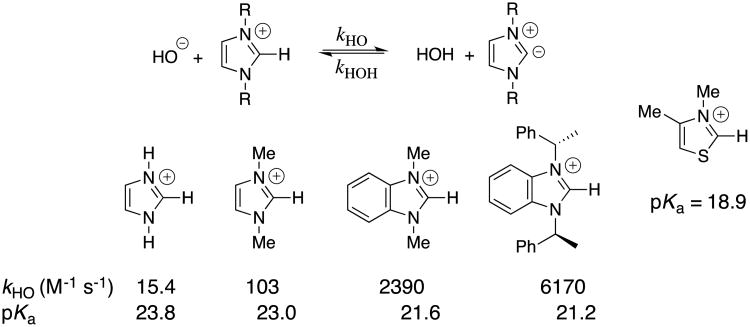

Our laboratories collaborated in examining the deuterium exchange reactions between solvent D2O and the C(2)-proton of simple imidazolium cations at 25 °C (Scheme 7).31 These data were evaluated to first obtain rate constants kHO for hydroxide ion-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions. Evidence was presented that the reverse protonation of imidazol-2-yl carbenes by solvent water is limited by solvent reorganization and occurs with a rate constant of kHOH = kreorg = 1011 s-1.13, 31 Combining the values of kHO and kHOH (Scheme 4B) gave the carbon acid pKas for ionization of the imidazolium cations at C(2) reported in chart 2.31 The value of pKa = 18.9 reported for the carbon ionization of the 3,4-dimethylthiazolium cation (chart 2) shows that thiazolium cations are stronger carbon acids than similarly substituted imidazolium cations.32 Recent reports from the literature provide examples of the scope for studies on substituent effects on these carbon acid pKas.33

Scheme 7.

The exchange reaction of deuterium from solvent D2O for the C(2)-proton that was examined for a series of a simple imidazolium cations.

Chart 2.

Second-order rate constants kHO and carbon acid pKas for ionization of imidazolium cations at C(2), calculated as shown in Scheme 4B. A representative carbon acid pKa for a thiazolium cation is also reported.

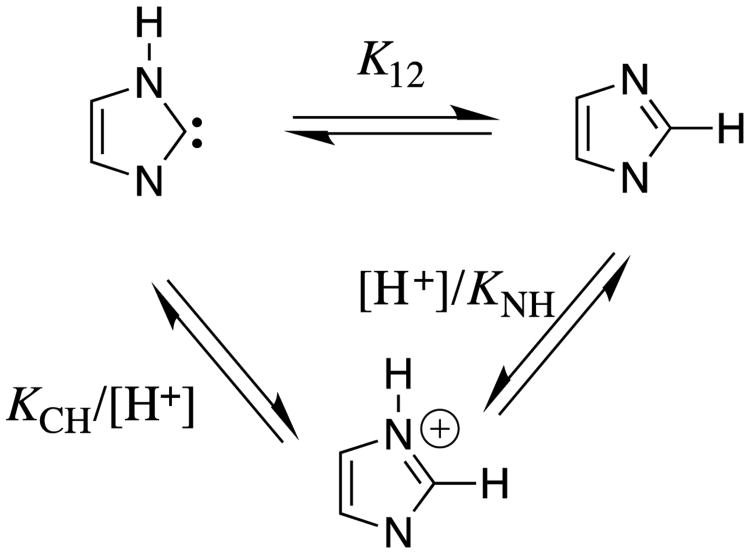

The relative acidity of the cationic nitrogen (pKa = 7.1) and of the neutral C(2) carbon at the imidazolium cation (pKa = 23.8, chart 2) defines the equilibrium constant of pK12 = 16.7 for the 1,2-hydrogen shift at the imidazole-2-yl carbene (eq 2, derived for Scheme 8). This hydrogen shift, which is thermodynamically favorable by 23 kcal/mol occurs by the stepwise mechanism shown in Scheme 8, because the concerted 1,2-hydrogen shift is symmetry forbidden,34 with a calculated activation barrier of between 40 and 47 kcal/mol.35

Scheme 8.

Thermodynamic cycle that shows the relationship between the nitrogen (KNH) and C(2) carbon (KCH) acidity of the imidazole cation; and, the equilibrium constant K12 for the 1,2-hydrogen shift at the imidazole-2-yl carbene.

| (2) |

5 The α–Carbon Acidity of Amino Acids, Peptides and Their Derivatives

I was asked to prepare a dipeptide in 1975, during a thoroughly nonproductive interlude in my graduate career, and learned that significant racemization of amino acids is observed during the course of peptide synthesis, under apparently mild conditions.36 I later learned that the halftime for epimerization of isoleucine in bones is > 100,0000 years;37 while, the aspartyl residues in dentin in the eye, and myelin undergo racemization at a rate of 0.1%/year.38 An examination of the literature showed that these anecdotal observations were symptomatic of the lack of rigor in discussions of the acidity of α–amino carbon of amino acids and their derivatives. We have worked to improve this situation.

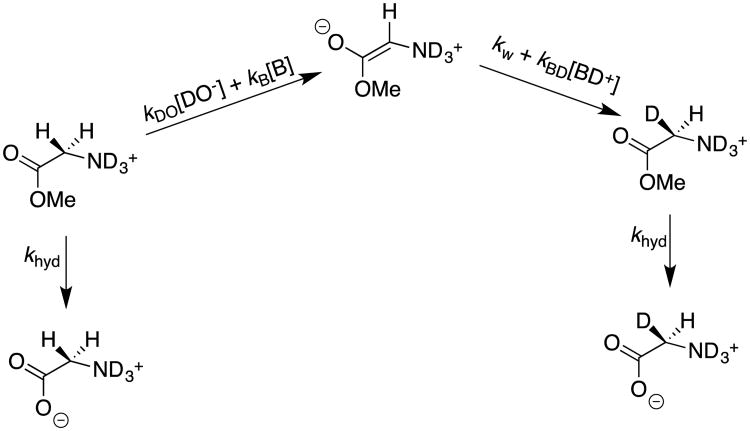

The observations of peptide racemization under mild synthetic conditions prompted Dr. Ana Rios to monitor the exchange of deuterium from solvent D2O for the α–hydrogen of N-protonated glycine methyl ester at room temperature and neutral pH, where she found that α–amino acid esters undergo competing base-catalyzed hydrolysis and deuterium exchange reactions (Scheme 9).39, 40 In cases where the hydrolysis reaction was significantly faster than deuterium exchange, hydrolysis was monitored until completion by 1H-NMR, and the relatively low deuterium enrichment of the product glycine was then determined. First-order rate constants kex for deuterium exchange were determined according to eq 3, where khyd is the first-order rate constant for hydrolysis, and fD < 0.10 is the fraction of glycine that contains a single deuterium.39

Scheme 9.

Competing hydrolysis and deuterium exchange reactions of N-protonated glycine methyl ester in D2O.

| (3) |

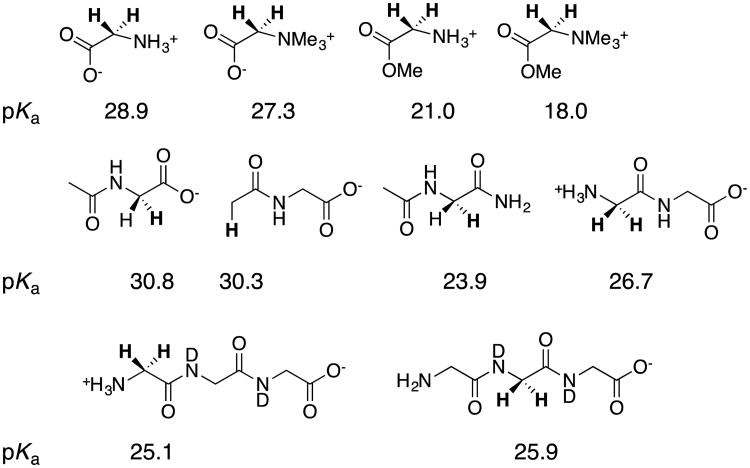

Dr. Rios next examined the base-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions of the α–amino hydrogen of glycine, betaine, glycine peptides and derivatives of these peptides. The data define the kinetic acidity of these carbon acids, and were used to provide estimates for the carbon acid pKas summarized in chart 3.39-41 Coote and coworkers have carried out computational studies to model the carbon acidity of substituted acetamides, diketopiperazines and linear dipeptides42 The results of their calculations on dipeptides were in good agreement with our experimental work.42

Chart 3.

The pKas for deprotonation of glycine, glycine derivatives; and, glycyl peptides and their derivatives, where the acidic hydrogen is shown in bold type.

Effect of Cationic –NR3+ Substituentson Carbon Acid pKa

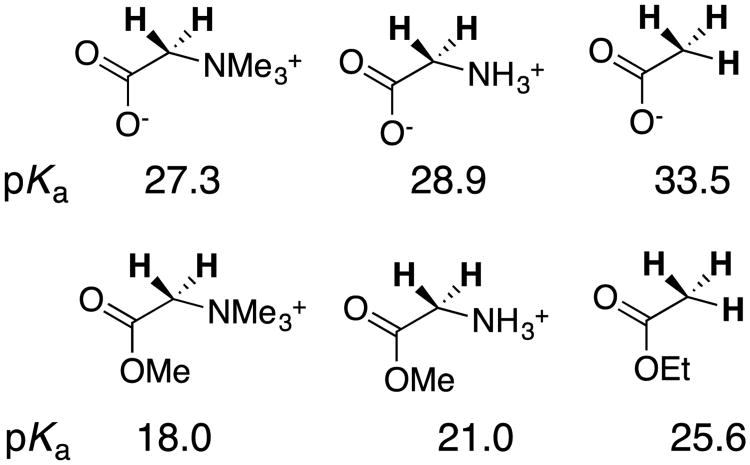

The α–NH3+ for -H substitution at acetic acid or ethyl acetate results in ca 4.5 unit decreases in carbon acid pKa, while an additional two to three unit reduction in pKas are observed for the corresponding α-NMe3+ substituted carbon acids (chart 4). We regarded these substituent effects on carbon acidity as large, until we learned of the enormous effect of changing medium on the -NMe3+ substituent effect on the oxygen acidity of carboxylic acids.43, 44 The addition of an -NMe3+ group to acetate ion results in a small 2.9 unit decrease in the pKa of the carboxylic acid (ΔΔGw = -4 kcal/mol), but this substitution results in an enormous -110 kcal/mol decrease in gas phase basicity, from 349 kcal/mol for CH3CO2- to 239 kcal/mol for +Me3NCH2CO2-.44 The ca 100 kcal/mol difference in the -NMe3+ substituent effects on deprotonation of glycine in the gas phase and water [ΔΔGg - ΔΔGw ≈ -100 kcal/mol] shows that the free energy of solvation of the trimethylammonium cation and carboxylate anion is ≈ 100 kcal/mol larger when these groups are located at separate molecules (ΔGRsolv), than when they are present at a single formally neutral zwitterion, (ΔGPsolv, [ΔGg - ΔGw = ΔGRsolv - ΔGPsolv, Scheme 10A).

Chart 4.

The effect of cationic nitrogen substituents on the acidity of the α–carbonyl carbon of acetate anion and ethyl acetate.

Scheme 10.

(A) Thermodynamic cycle that compares the deprotonation of betaine by acetate anion in the gas phase and in water. The difference in the change in Gibbs free energy for the reaction in these two media ([ΔGg - ΔGw ≈ -100 kcal/mol] is equal to the difference in the change in Gibbs free energy for transfer of reactants, compared with the transfer of products from the gas phase to water (ΔGRsolv - ΔGPsolv). (B) Cycle that compares deprotonation of N-protonated proline by a thiolate anion at the nonpolar enzyme active site for proline racemase,48 and the corresponding proton transfer in water. A larger affinity of the hydrophobic enzyme active site for binding the carbanion zwitterion, compared with the cationic substrate, from water will result in a smaller barrier to substrate deprotonation at the enzyme compared to water.

We reasoned as follows in proposing that the weak solvation of zwitterions compared to separated free ions has profound consequences with respect to the mechanism for enzymatic catalysis of carbon deprotonation of N-protonated amino acids to form the carbanion zwitterion (Scheme 10B);39, 45 the first step in the racemization or epimerization of amino acids catalyzed by enzymes such as proline racemase,46-48 glutamate racemase,49, 50 and diaminopimelate epimerase.51

The effect of changing medium on the substituent effect for deprotonation of cationic amino acids at the α–carbon and at the carbonyl oxygen is predicted to be similar, because the product of each reaction is a zwitterion and is more poorly solvated than the corresponding free ions (Scheme 10A).43, 44

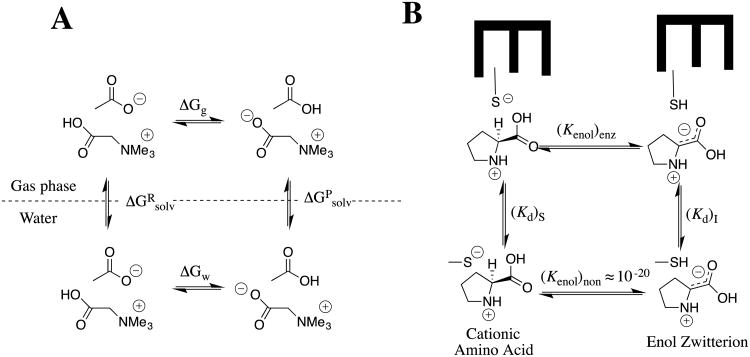

The large activation barrier to base-catalyzed deprotonation of the α–carbon of cationic amino acids in water at pH 7 is due mainly to the large thermodynamic barrier to formation of the enolate (Kenol)non ≈ 10-20 (Scheme 10B).52 This barrier must be reduced in order to obtain efficient catalysis of amino acid racemization through a carbanion zwitterion intermediate.

The activation barrier for enzyme-catalyzed carbon deprotonation of N-protonated proline is lowered by the transfer of the cationic amino acid from aqueous solution to a nonpolar active site, where the apparent dielectric is substantially smaller than D = 79 for water (Scheme 10). The difference in the free energy for transfer of the enolate zwitterion from water to a nonpolar enzyme active should be substantially smaller than the ca. free energy 100 kcal/mol difference for transfer from water to the gas-phase,43, 44 because the “effective” dielectric constant at the enzyme active site is larger than D = 1 for the gas phase.45

This proposal is supported by the results of a QM/MM computational study on glutamate racemase-catalyzed deprotonation of the α–carbon of glutamate.53 The substrates for proline racemase,48 glutamate racemase,50 and diaminopimelate epimerase51 are bound at enzyme active sites that resemble “cages”,54 where the apparent dielectric constant of the engulfing protein is substantially smaller than for aqueous solution.55 This proposed effect of such hydrophobic active sites on reactivity provide a simple rationale for the otherwise difficult to fathom rate accelerations for substrate deprotonation. This proposal has not been strongly criticized, nor is it universally accepted,47, 56 perhaps because of the difficulty in accepting this passive role for exceptionally active enzymes, in achieving their large catalytic rate accelerations.

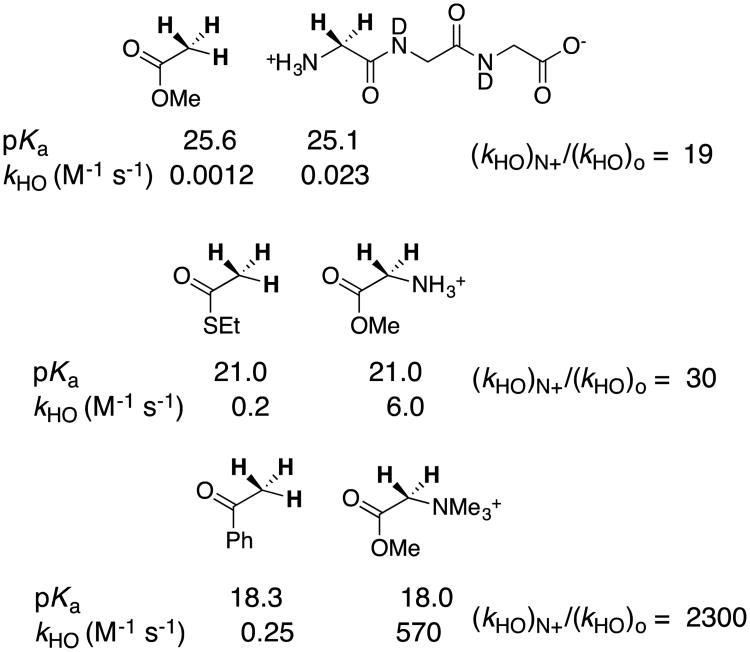

Effect of Cationic Substituents on Intrinsic Barriers for Carbon Deprotonation

chart 5 shows that a cationic α–NH3+ substituted amide has a carbon acid pKa similar to that for a neutral ester, while cationic α–NH3+ and α–NMe3+ substituted esters show carbon acid pKas that are similar to that for a neutral thioester and ketone, respectively. More importantly, chart 5 shows that cationic α-carbonyl carbon acids undergo lyoxide anion-catalyzed deprotonation from (20–2000)-fold faster than neutral carbon acids of similar pKa.39, 41 There is a (20 – 2000)-fold kinetic advantage to protonation of the enolate zwitterions in the microscopic reverse direction. In other words, the cationic α–NH3+ and α–NMe3+ substituents result in decreases in the activation barriers for proton transfer that are larger than expected for their very small effects on reaction driving force.

Chart 5.

A comparison of the thermodynamic (pKa) and kinetic acidity (kHO for hydroxide catalyzed deprotonation) of neutral and cationic carbon acids. The paired carbon acids show similar pKas, and a significantly larger rate constant kHO for deprotonation of the cationic acid.

The kinetic activation and thermodynamic reaction barriers for carbon deprotonation and other reactions may be normalized to obtain Marcus intrinsic reaction barriers λ for hypothetical thermoneutral proton transfer, when there is no thermodynamic reaction barrier [ΔG° = 0].57 This Marcus formalism allows the separation of substituent effects on organic reactivity into the effects on reaction driving force ΔG° and reaction intrinsic barrier λ.16, 58, 59 The results summarized in chart 5 show that cationic α–NR3+ result in significant decreases in the intrinsic barrier λ for proton transfer reactions at α–carbonyl carbon.

There is compelling evidence that the intrinsic barriers λ for protonation of enolates and related resonance stabilized carbanions increase systematically with increasing delocalization of negative charge from carbon to oxygen, culminating in the large λ for protonation of the nitromethyl carbanion, where negative charge lies nearly exclusively at the nitronate oxygens.25 A. Jerry Kresge,60 William P. Jencks,61 and Claude Bernasconi58 have proposed closely related models to rationalize changes in the intrinsic barriers observed for a wide range of chemical reactions of resonance stabilized reactive intermediates. A description of the rational for these models lies outside the scope of this review, but each predicts that decreases in the intrinsic barrier for protonation of enolate zwitterions, compared with simple enolates, reflects the reduced resonance stabilization and the greater localization of negative charge at the α-carbon for the enolate zwitterion. We have proposed that the shift in negative charge away from the electronegative oxygen and toward the α–carbon at enolate zwitterions is driven by an increase in columbic stabilization observed with decreasing distance separating the interacting charges (Scheme 11).16, 39, 45

Scheme 11.

Valence bond resonance structures for an enolate zwitterion. The structure on the right, with negative charge localized at carbon, provides for optimal stabilizing polar interactions at the zwitterion, and is proposed to make a larger contribution to the overall structure of cationic enolates compared with simple enolates.

6 Electrophilic Catalysis of Deprotonation of Amino Acids: The α-Carbon Acidity of Iminium Cations

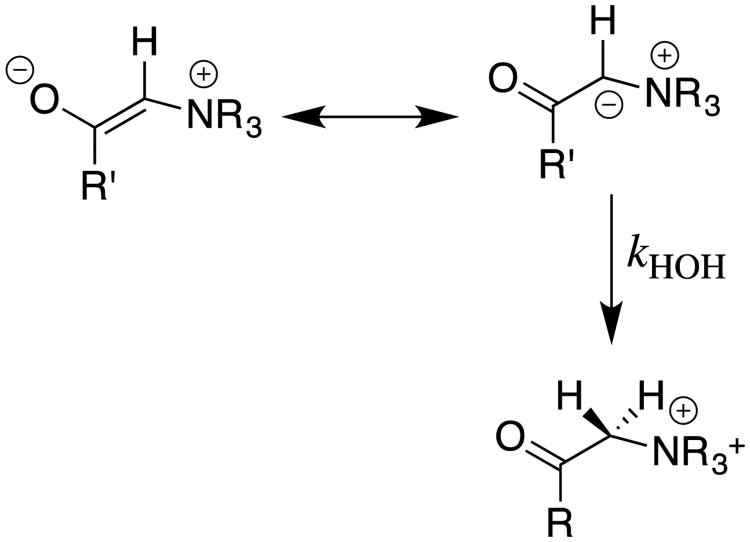

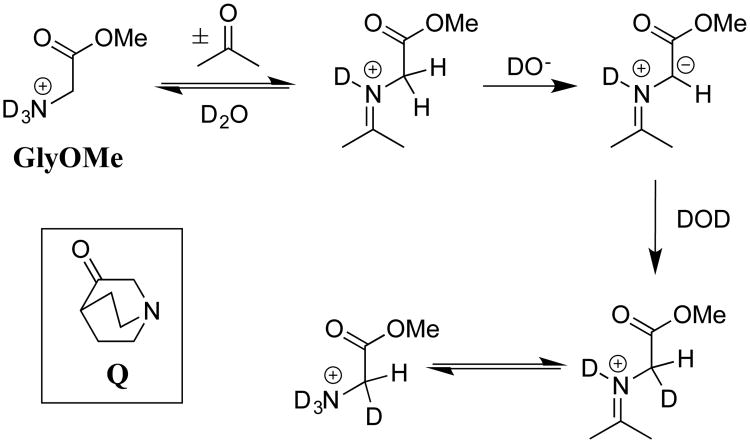

Our studies on carbon acidity, which were initiated more than twenty-five years ago, represent our best efforts to demonstrate that the decline in interest in classical studies of reaction mechanisms in solution in no way reflects the lack of significant and appealing problems to solve. In recent years, we have worked to transition to investigations of reactions that occur at enzyme active sites, and to direct studies on the mechanism of enzyme action. This transition was facilitated by Dr. Ana Rios's unpublished observation that the small tertiary amine 3-quinuclidinone (Q, Scheme 12) acts as a bifunctional electrophilic and general base catalyst of carbon deprotonation of glycine methyl ester (GlyOMe) in aqueous solution. We proposed that bifunctional catalysis results from activation of GlyOMe through formation of an iminium ion adduct to the carbonyl functional group of Q, and that this iminium ion undergoes deprotonation at the α-imino carbon by a second Q. We evaluated electrophilic catalysis by examining the deprotonation of GlyOMe catalyzed by acetone. This study showed that the efficiency of this simple ketone arises from the 7-unit decrease in the carbon acid pKa of 21 for the α-amino carbon of N-protonated Gly-OMe to a pKa of 14 for the α-imino carbon of the iminium ion adduct (Scheme 12).62

Scheme 12.

The mechanism for catalysis of deprotonation of Gly-OMe by the coordinated action of the ketone acetone and the Brønsted base DO-. The tertiary amine 3-quinuclidinone (Q) acts as a bifunctional catalyst of deprotonation of Gly-OMe through formation of an iminium ion adduct in the first step, and action as a general base catalyst of deprotonation of this adduct in the second step.

We were surprised by the large effect of formation of amino acid adducts to the carbonyl group, on the acidity of α-amino carbon (Scheme 12). These results emphasized the sensitivity of the pKa of the α-carbon to changes in hybridization at the nitrogen substituent, and to the presence of alkyl groups at this nitrogen.39, 62, 63 This suggests that chiral ketones may serve as powerful organo-catalysts in enantioselective syntheses of chiral α-amino acids from glycine and suitable carbon electrophiles.

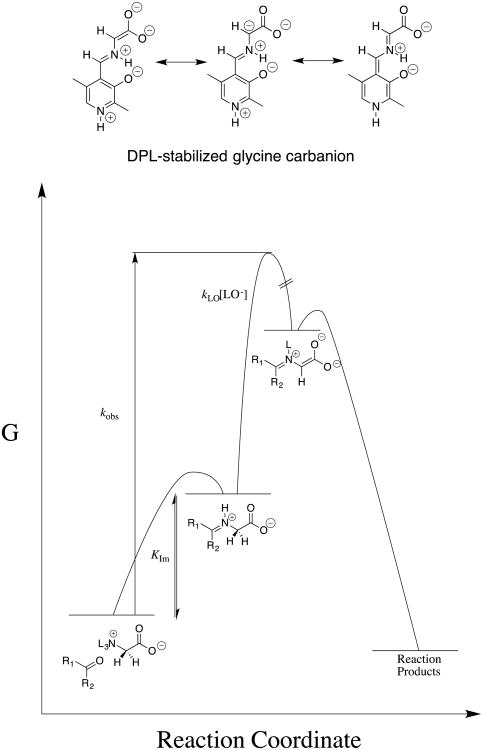

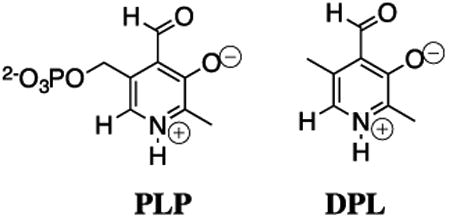

Our early experimental results showed that much of the power of the biological electrophilic catalyst pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) resides in the carbonyl functional group. This prompted experiments to compare the electrophilic reactivity of acetone, 5′-deoxypyridoxal (DPL) and other carbonyl compounds as catalysts of the deprotonation of glycine. One result that caused much confusion was the great difficulty experienced in detecting DPL-catalyzed exchange of deuterium from solvent D2O into the α-carbon of glycine, because we knew that DPL was a powerful electrophilic catalyst of deprotonation of glycine. We eventually demonstrated that the relatively rapid formation of the DPL-stabilized glycine carbanion by deprotonation of the DPL-glycine iminium ion is effectively irreversible under our reaction conditions, and the rate-determining step for Claisen-type addition of the DPL-stabilized glycine carbanion to the carbonyl group of a second molecule of DPL to form an enantiomeric mixture of DPL-glycine adducts (chart 6).64 The rate constants for deprotonation of the α-iminium carbon of the DPL-glycine iminium cation (pKa = 17, chart 7) were determined by monitoring the disappearance of DPL at 412 nm in this Claisen-type reaction.65 The products of two additional Claisen-type condensation reactions of DPL-stabilized carbanions in water were characterized (chart 6).66, 67 The addition reactions of DPL-stabilized amino acid carbanions to DPL in water reflects the high carbanion selectivity for addition to the carbonyl group, over protonation by buffer acids.

Chart 6.

The products of Claisen-type addition reactions of DPL-stabilized amino acid carbanions. (A) Products from addition of the DPL-stabilized glycine carbanion to DPL.64 (B) Products from addition of the α-pyridyl carbon of the DPL-stabilized alanine carbanion to DPL.66 (C) Products from addition of the DPL stabilized glycine carbanion to the α-imino carbon of the DPL-glycine iminium cation.67

Chart 7.

Carbon acid pKas for deprotonation of the α-amino carbon of N-protonated glycine, the α-ammonium carbon of pyridinium dication, and the α-imino carbon of the adduct of glycine to the following carbonyl compounds; acetone; DPL, benzaldehyde, salicylaldehyde, and phenyl glyoxalate.

The results of experiments to characterize the reactivity of different aldehydes and ketones as catalysts of deprotonation of glycine are summarized in chart 7 as the carbon acid pKas for the corresponding glycine iminium cations.63, 65, 68, 69 These pKas were estimated from the observed rate constants for the ketone-catalyzed reactions, and equilibrium constants for formation of the reactive iminium ions from glycine and the respective carbonyl compounds,70 which define the contribution of this reaction barrier to the overall barrier for carbon deprotonation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Free energy reaction profile which shows that the overall activation barrier for carbonyl-catalyzed deprotonation of glycine to form a stabilized glycine carbanionis composed of the barrier for conversion of the reactants to the iminium cation and, the barrier for deprotonation of this cation by lyoxide anion. The carbonyl-catalyzed reactions were generally followed by monitoring protonation of the carbanion reaction intermediate in DOD to give deuterium-labeled glycine. However, the disappearance of DPL was monitored during formation of the Claisen-type adduct shown in Chart 6.64

The carbon acid pKas reported in chart 7 show the following.

Formation of the glycine-acetone iminium cation results in 9.5 kcal/mol increase in the driving force for deprotonation of the α-amino carbon of glycine. This is more than 50% of the 16.3 kcal/mol effect of formation of the glycine-DPL iminium cation on the reaction driving force.

The difference between the pKas of 17 and 25 for deprotonation of the glycine-DPL and glycine-salicylaldehyde iminium cations shows that the cationic pyridine nitrogen results in an 11 kcal/mol increase in the driving force for deprotonation of the α-iminium carbon.

The lower pKa of 14 compared with 17 for deprotonation of the α-iminium carbon of the glycine-phenylglyoxalate and glycine-DPL iminium cations, respectively, illustrates the large potential for simple ketone catalysis of the deprotonation of α-amino carbon.

The defining feature of catalysis by PLP is the effective delocalization of negative charge across both the α-imino and α-pyridyl carbons of PLP-stabilized amino acid carbanions. This enables efficient cofactor catalysis of transamination reactions of amino acids.71 The low carbon acid pKa of 18 for deprotonation of the α-NH3+ carbon of the pyridinium dication is one measure of the effectiveness of delocalization of charge onto the cationic pyridinium ring.68

7 pKas for Carbon Acids at Enzyme Active Sites

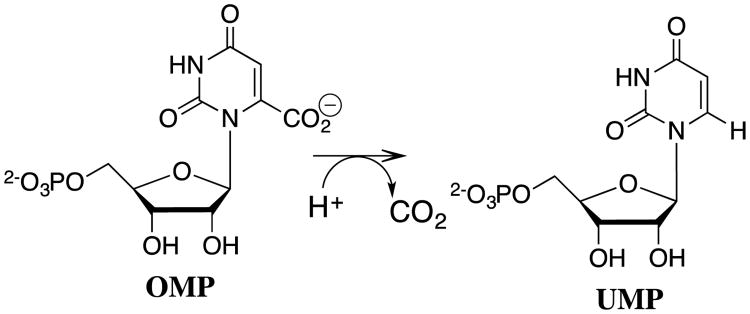

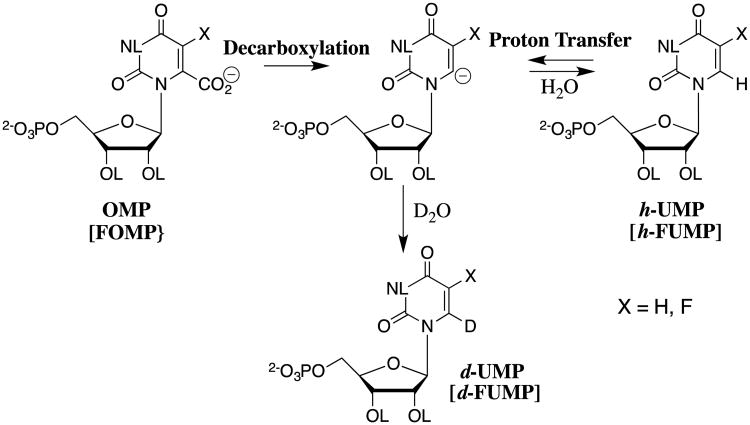

Most recently, we have adopted procedures used to characterize the acidity of weak carbon acids in studies on the effect of enzyme catalysts on the acidity of protein bound substrates.72, 73 The results of studies on the very difficult decarboxylation of orotidine 5′-monophosphate (OMP) to give uridine 5′-monophosphate (UMP, Scheme 13) catalyzed by orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC) demonstrate the power of these protocols to provide insight into enzymatic reaction mechanisms.73-76

Scheme 13.

The decarboxylation of orotidine 5′-monophosphate (OMP) to give uridine 5′-monophosphate (UMP) catalyzed by orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC).

The mechanism of OMPDC was controversial for several years, because of the seemingly enormous 31 kcal/mol transition state stabilization required for simple decarboxylation through a vinyl carbanion reaction intermediate (Scheme 14).77 It was suggested that “ …. the 1023 M-1 proficiency of ODC must arise from covalent catalysis, since only 1011 M-1 proficiency is possible by noncovalent binding”.78 The proposed mechanisms for covalent catalysis appeared unattractive,79 but difficult to rigorously exclude.

Scheme 14.

The decarboxylation of OMP and FOMP, and the deuterium exchange reactions of UMP and FUMP in D2O through common vinyl carbanion reaction intermediates.

The activation barrier to the nonenzymatic decarboxylation of OMP (t1/2 = 78 million years) is effectively equal to the thermodynamic barrier to formation of the highly unstable C-6 UMP vinyl carbanion (Scheme 14). We took the position that the power of proteins as catalysts was underappreciated, and that the UMP vinyl carbanion is a viable reaction intermediate. We reasoned that if the UMP carbanion forms at the active site of OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP, then it must also form by direct deprotonation of UMP by OMPDC for reaction in the reverse direction, and might therefore be detected in a study of OMPDC-catalyzed transfer of deuterium from solvent D2O to UMP (Scheme 14). This prediction was confirmed in studies on the OMPDC-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions of UMP,73 on the much faster OMPDC-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions of 5-fluoroorotidine 5′-monophosphate (FUMP),74 and on the phosphate dianion activated OMPDC-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions of the phosphodianion truncated substrate 1-(β-D-erythrofuranosyl)-5-fluoroorotic acid.76

This observation of strong catalysis by OMPDC of the difficult deuterium exchange reactions of UMP and FUMP shows that the binding of these ligands results in a large increase in the driving force for deprotonation to form the respective carbanions, through the development of strong stabilizing interactions with the protein catalyst.80 These interactions may be quantified through the determination of the effect of binding of UMP and FUMP to OMPDC on the carbon acidity of C-6.

The estimated equilibrium constants for proton transfer reactions between OMPDC and enzyme-bound UMP or FUMP (Scheme 15) were obtained in experiments that measure the difference in the pKas for the reacting substrate and basic side chain at the enzyme.74 This difference in pKas was combined with the pKa of the enzyme side chain to give the carbon acid pKas reported in Scheme 15.74 There is a large 3.7-unit effect of a single C-5 fluorine on the carbon acid pKa of enzyme-bound UMP. This effect is consistent with transmission of the polar effect of the electron-withdrawing fluorine at an enzyme active site of low apparent dielectric constant.45

Scheme 15.

Estimated carbon acid pKas for C-6 deprotonation of uridine and fluorouridine in water [R = H, (pKa)w] and of UMP and FUMP at the active site of OMPDC [(R = -PO32-), (pKa)E]. The values of [(pKa)w] for ionization in water were estimated from the second-order rate constant kLO for the lyoxide-catalyzed deuterium reaction,74 as described by Scheme 4B. The values of [(pKa)E] were determined in an analysis of the kinetics for OMPDC-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions of UMP and FUMP, which showed that substrate binding to OMPDC results in a ≥ 5 × 109-fold increase in the equilibrium constant for deprotonation at C-6. The values of (pKa)E are upper limits, because of the uncertainty in the rate constant for protonation of the UMP and FUMP carbanions at the enzyme active site.

8 Concluding Remarks

The planning and execution of our first studies to determine the carbon acid pKa of ethyl thioacetate was carried out too many years ago, as young investigators. The success of this study was cause for excitement,7 as we came to understand the sizeable gaps in our understanding of the mechanisms for proton transfer reactions at carbon. We have filled a few of these gaps over the past 25 years. After passage of this considerable time, we maintain our strong conviction that the topic of the mechanisms of polar organic reactions remains vibrant, fertile, and filled with important problems ripe for solution through creative investigations. We feel mostly sadness in watching as so many important problems are being forgotten.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the US National Institutes of Health Grants GM116921 and GM039754 for generous support of our work.

Biographies

Tina L. Amyes received BA and MA degrees in Natural Science from Cambridge University, and her PhD degree in Chemistry from the same University working with Anthony J. Kirby. She learned Physical Organic Chemistry from Tony Kirby and the MD William P. Jencks and in 1988 began a collaboration with John Richard that lasted for 25 years. She currently serves as Team Science Grant Coordinator at the Roswell Park Cancer Institutes.

John P. Richard received a BS in Biochemistry and a PhD in Chemistry (1979) from The Ohio State University working with Perry Frey. He learned Physical Organic Chemistry from the MD William P. Jencks and next worked with Irwin P. Rose and Anthony J. Kirby, before joining the faculty at the University of Kentucky in 1985. In 1993 he moved to the University at Buffalo (SUNY) where he is now Distinguished Professor of Chemistry. Richard has delineated important imperatives for many polar organic reactions, including proton and hydride transfer, nucleophilic addition to carbocations and to aliphatic carbon, carbocation-anion pair rearrangements, alkene-forming elimination and decarboxylation. He has along-standing interest in understanding the mechanism by which carbanion and carbocation intermediates of enzymatic reactions are stabilized by interactions with protein catalysts, and has demonstrated a general mechanism for obtaining specificity in intermediate binding to protein catalysts.

References

- 1.Jencks WP. Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1969. p. 519. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lienhard GE, Wang TC. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:3781–3787. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurz LC, Shah S, Crane BR, Donald LJ, Duckworth HW, Drysdale GR. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7899–7907. doi: 10.1021/bi00149a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thibblin A, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:4963–4973. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richard JP. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:1535–1573. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearson RG, Dillon RL. J Am Chem Soc. 1953;75:2439–2443. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10297–10302. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jencks WP. Acc Chem Res. 1980;13:161–169. [Google Scholar]; Jencks WP. Acc Chem Res. 1976;9:425–432. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:4926–36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jencks WP, Gresser MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:6963–6970. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tapuhi E, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:5758–5765. [Google Scholar]; Chiang Y, Kresge AJ, Tang YS, Wirz J. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:460–462. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3129–3141. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richard JP, Williams G, Gao J. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:715–726. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richard JP, Williams G, O'Donoghue AC, Amyes TL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2957–2968. doi: 10.1021/ja0125321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amyes TL, Richard JP. Proton transfer to and from carbon in model reactions. Vol. 2007. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2007. pp. 949–973. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richard JP, Amyes TL, Toteva MM. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:981–988. doi: 10.1021/ar0000556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaatze U, Pottel R, Schumacher A. J Phys Chem. 1992;96:6017–6020. [Google Scholar]; Kaatze U. Journal of Chemical Engineering Data. 1989;34:371–374. [Google Scholar]; Giese K, Kaatze U, Pottel R. J Phys Chem. 1970;74:3718–3725. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amyes TL, Richard JP, Jagannadham V. Spec Publ - R Soc Chem. 1995;148:334–350. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keeffe JR, Kresge AJ. Kinetics and mechanism of enolization and ketonization. In: Rappoport Z, editor. The Chemistry of Enols. John Wiley and Sons; Chichester: 1990. pp. 399–480. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiberg KB, Ochterski J, Streitwieser A. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8291–8299. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jagannadham V, Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:8465–8466. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hojatti M, Kresge AJ, Wang WH. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:4023–4028. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahrens ML, Eigen M, Kruse W, Maas G. Ber Bunsen-Ges Phys Chem. 1970;74:380–385. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoefnagel AJ, Hoefnagel MA, Wepster BM. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:6194–6197. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiberg KB, Castejon H. J Org Chem. 1995;60:6327–6334. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrmann WA, Köcher C. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1997;36:2162–2187. [Google Scholar]; Kaufhold S, Petermann L, Staehle R, Rau S. Coord Chem Rev. 2015;304-305:73–87. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bourissou D, Guerret O, Gabbaie FP, Bertrand G. Chem Rev. 2000;100:39–91. doi: 10.1021/cr940472u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiang PC, Bode JW. RSC Catal Ser. 2011;6:399–435. [Google Scholar]; Breslow R. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:3719–3726. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomson JE, Rix K, Smith AD. Org Lett. 2006;8:3785–3788. doi: 10.1021/ol061380h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nyce GW, Lamboy JA, Connor EF, Waymouth RM, Hedrick JL. Org Lett. 2002;4:3587–3590. doi: 10.1021/ol0267228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arduengo AJ., III Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:913–921. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amyes TL, Diver ST, Richard JP, Rivas FM, Toth K. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4366–4374. doi: 10.1021/ja039890j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Washabaugh MW, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:674–683. [Google Scholar]; Washabaugh MW, Jencks WP. Biochemistry. 1988;27:5044–5053. doi: 10.1021/bi00414a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massey RS, Quinn P, Zhou S, Murphy JA, O'Donoghue AC. J Phys Org Chem. 2016;29:735–740. [Google Scholar]; Massey RS, Collett CJ, Lindsay AG, Smith AD, O'Donoghue AC. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:20421–20432. doi: 10.1021/ja308420c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alder RW. Diaminocarbenes: Exploring Structure and Reactivity. In: Bertrand G, FontisMedia SA, editors. Carbene Chemistry. Marcel Dekker Inc.; 2002. pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maier G, Endres J. Eur J Org Chem. 1998:1517–1520. [Google Scholar]; Mc Gibbon GA, Heinemann C, Lavorato DJ, Schwarz H. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1997;36:1478–1481. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kemp DS. Racemization in Peptide Synthesis. In: Undenfriend S, Meienhofer J, editors. The Peptides. Vol. 1 Academic Press; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bada JL, Kvenvolden KA, Peterson E. Nature. 1973;245:308–310. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helfman PM, Bada JL. Nature. 1976;262:279–281. doi: 10.1038/262279b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rios A, Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9373–9385. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rios A, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:8375–8376. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rios A, Richard JP, Amyes TL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:8251–8259. doi: 10.1021/ja026267a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ho J, Coote ML, Easton CJ. J Org Chem. 2011;76:5907–5914. doi: 10.1021/jo200994z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ho J, Easton CJ, Coote ML. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5515–5521. doi: 10.1021/ja100996z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patrick JS, Yang SS, Cooks RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:231–232. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price WD, Jockusch RA, Williams ER. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:3474–3484. doi: 10.1021/ja972527q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richard JP, Amyes TL. Bioorg Chem. 2004;32:354–366. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rudnick G, Abeles RH. Biochemistry. 1975;14:4515–4522. doi: 10.1021/bi00691a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubinstein A, Major DT. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8513–8521. doi: 10.1021/ja900716y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buschiazzo A, Goytia M, Schaeffer F, Degrave W, Shepard W, Grégoire C, Chamond N, Cosson A, Berneman A, Coatnoan N, Alzari PM, Minoprio P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1705–1710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lundqvist T, Fisher SL, Kern G, Folmer RHA, Xue Y, Newton DT, Keating TA, Alm RA, de Jonge BLM. Nature. 2007;447:817–822. doi: 10.1038/nature05689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hwang KY, Cho CS, Kim SS, Sung HC, Yu YG, Cho Y. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:422–426. doi: 10.1038/8223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pillai B, Cherney MM, Diaper CM, Sutherland A, Blanchard JS, Vederas JC, James MNG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8668–8673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602537103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams G, Maziarz EP, Amyes TL, Wood TD, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8354–8361. doi: 10.1021/bi0345992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Puig E, Garcia-Viloca M, González-Lafont A, Lluch JM. The journal of physical chemistry A. 2006;110:717–725. doi: 10.1021/jp054555y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Richard JP, Amyes TL, Goryanova B, Zhai X. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2014;21:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kukic P, Farrell D, McIntosh LP, García-Moreno EB, Jensen KS, Toleikis Z, Teilum K, Nielsen JE. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16968–16976. doi: 10.1021/ja406995j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Simonson T, Carlsson J, Case DA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4167–4180. doi: 10.1021/ja039788m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Möbitz H, Bruice TC. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9685–9694. doi: 10.1021/bi049580t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marcus RA. J Phys Chem. 1968;72:891–899. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bernasconi CF. Acc Chem Res. 1987;20:301–308. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Richard JP, Amyes TL, Williams KB. Pure Appl Chem. 1998;70:2007–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kresge AJ. Can J Chem. 1974;52:1897–1903. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jencks DA, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:7948–7960. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rios A, Crugeiras J, Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7949–7950. doi: 10.1021/ja016250c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Crugeiras J, Rios A, Riveiros E, Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2041–2050. doi: 10.1021/ja078006c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Toth K, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Malthouse JPG, NiBeilliu ME. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10538–10539. doi: 10.1021/ja047501v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toth K, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3013–3021. doi: 10.1021/ja0679228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Go MK, Richard JP. Bioorg Chem. 2008;36:295–298. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toth K, Gaskell LM, Richard JP. J Org Chem. 2006;71:7094–7096. doi: 10.1021/jo061090e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crugeiras J, Rios A, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:2145–2149. doi: 10.1039/b504399a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Crugeiras J, Rios A, Riveiros E, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3173–3183. doi: 10.1021/ja110795m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Crugeiras J, Rios A, Riveiros E, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15815–15824. doi: 10.1021/ja906230n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Richard JP, Amyes TL, Crugeiras J, Rios A. Biochim Biophys Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2011;1814:1419–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Richard JP, Amyes TL, Crugeiras J, Rios A. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.O'Donoghue AC, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2622–2631. doi: 10.1021/bi047953k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; O'Donoghue AC, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2610–2621. doi: 10.1021/bi047954c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Amyes TL, Wood BM, Chan K, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1574–1575. doi: 10.1021/ja710384t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tsang WY, Wood BM, Wong FM, Wu W, Gerlt JA, Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:14580–14594. doi: 10.1021/ja3058474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goryanova B, Goldman LM, Amyes TL, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2013;52:7500–7511. doi: 10.1021/bi401117y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goryanova B, Amyes TL, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:6545–6548. doi: 10.1021/ja201734z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Radzicka A, Wolfenden R. Science. 1995;267:90–93. doi: 10.1126/science.7809611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang X, Houk KN. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:379–385. doi: 10.1021/ar040257s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stanton CL, Kuo IFW, Mundy CJ, Laino T, Houk KN. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:12573–12581. doi: 10.1021/jp074858n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pauling L. Nature. 1948;161:707–709. doi: 10.1038/161707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]