Abstract

The U.S. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) showed that lifestyle participants who achieved ≥7% weight loss and ≥150 min/week physical activity experienced the greatest reduction in type 2 diabetes incidence. Demographic, clinical, and program factors that are related to achieving both these lifestyle goals have seldom been explored in community-delivered DPP programs. The purpose of this investigation is to examine factors associated with concurrent achievement of weight loss and physical activity goals in a 12-month community DPP lifestyle intervention. Adults [n = 223; age = 58.4 (SD = 11.5); BMI = 33.8 (SD = 6.0)] with glucose or HbA1c values in the pre-diabetes range and/or metabolic syndrome risk factors enrolled from one worksite and three community centers in the Pittsburgh, PA metropolitan area between January 2011 and January 2014. Logistic regression analyses determined the demographic, clinical and program adherence factors related to goal achievement at 6, 12, and 18 months. Participants achieving both intervention goals at 6 months (n = 57) were more likely to attend sessions [Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) =1.48], self-weigh (AOR = 1.19), and self-monitor behaviors (AOR = 1.18) than those meeting neither goal (n = 35; all p < 0.05). Baseline BMI (AOR = 0.87, p < 0.01), elevated glycemic status (AOR = 0.49, p < 0.05), and female sex (AOR = 0.52, p < 0.05) were inversely related to goal achievement at 6 months. Meeting either lifestyle goal at 6 months had the strongest association with meeting both goals at 12 and 18 months. Our study supports the importance of early engagement, regular attendance, self-monitoring, and self-weighing for goal achievement. Dissemination efforts should consider alternative approaches for those not meeting goals by 6 months to enhance long-term success.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13142-017-0494-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Physical activity, weight loss, community health, behavior change

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are prevalent conditions associated with significant personal and societal burden [1, 2]. Numerous diabetes prevention efficacy [3–6] and effectiveness studies [7, 8] have demonstrated that behavioral lifestyle programs can help individuals achieve weight loss (WL), increase physical activity (PA) levels, and in turn, improve diabetes and CVD risk factors. Adaptations of the efficacious lifestyle intervention utilized in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) [3] are currently being disseminated in the community, and can provide important data on the various factors (e.g. participant and program adherence characteristics) that impact WL and PA goal achievement.

Demographic, clinical, and program adherence factors related to WL and PA goal achievement have been reported in efficacy trials [9, 10], but have seldom been reported in DPP translation studies of healthy lifestyle intervention in the community [11–14]. The DPP demonstrated that concurrent achievement of WL and PA goals by lifestyle participants was associated with the greatest reduction in diabetes incidence [15]. Despite this observation, there are currently no known community DPP translation efforts that have examined the factors that are associated with participant achievement of both the WL and PA goals after intervention or at longer term follow-up. One community study, The Montana Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes Prevention Program [11, 14] reported factors related to achievement of each of the lifestyle goals for WL and PA. However, the goals were evaluated separately and factors common among participants meeting both goals were not examined.

Information on factors related to achievement of both lifestyle goals could further understanding of effective public health delivery of evidence-based lifestyle interventions. This investigation aims to identify the participant baseline demographic and clinical characteristics and the program adherence factors associated with meeting both program goals of ≥7% WL and ≥150 min/week PA in a one-year program adapted from the DPP lifestyle intervention. This will be the first known community translation study to evaluate factors related to both goals that, once identified, may help tailor diabetes prevention efforts to enhance participant likelihood of success.

Methods

This investigation examined data from a randomized clinical trial conducted within a corporate worksite and three senior community centers in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania metropolitan area. A detailed description of the study design, worksite and community partnerships, recruitment methods, and results of primary and secondary outcomes have been reported elsewhere [16–20]. In brief, study investigators collaborated with worksite and community partners to develop recruitment and implementation plans for delivering the study intervention at each site. Eligible participants were randomized to either an immediate-start lifestyle intervention or to a 6-month wait-list delayed control group. Those assigned to the latter condition received the intervention in its entirety at the end of the delay. The secondary analyses reported herein combine all randomized participants to address the research question. The study protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Participants

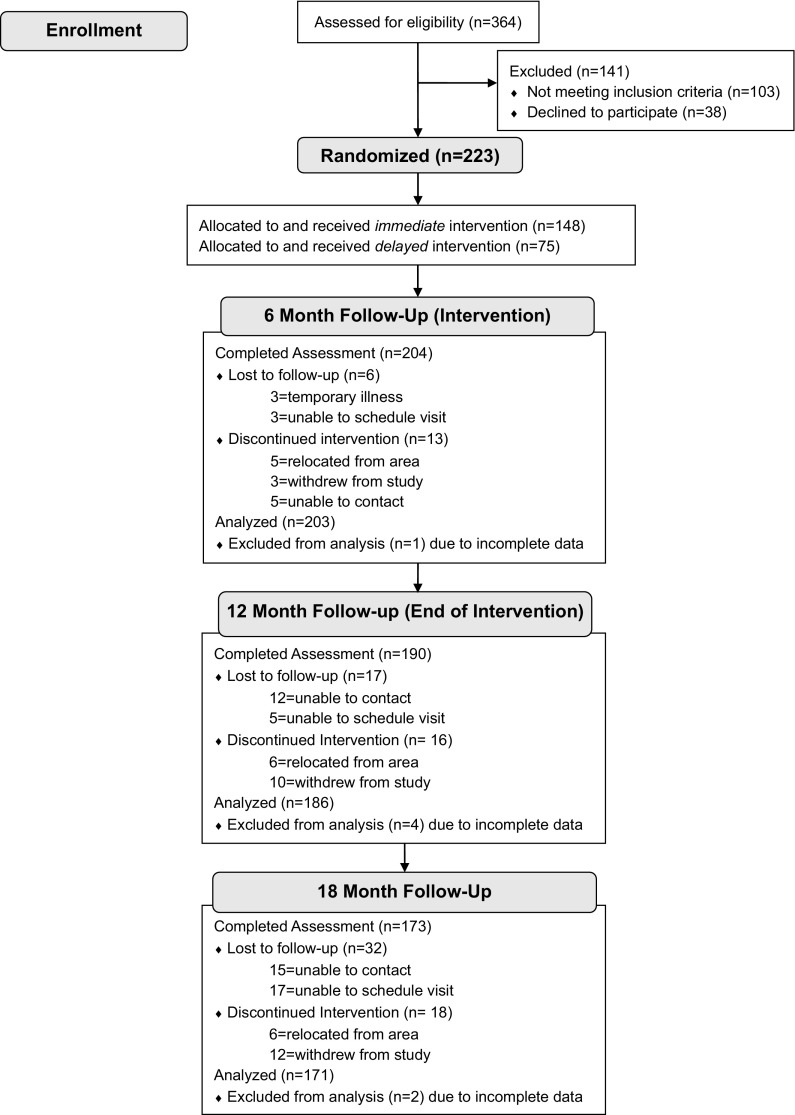

Individuals completing screening (n = 364) and who met the eligibility criteria (n = 261) were invited to participate. Eligibility included a BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2 (≥ 22 kg/m2 for Asians) and at least one of the following: (1) glucose or HbA1c screening values in the pre-diabetes range [21], (2) screening values indicative of the metabolic syndrome (NCEP ATP-III criteria; [22]), or (3) treatment for hyperlipidemia and at least one additional component of the metabolic syndrome. Individuals with a previous diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes or with screening values in the diabetes range [21] were excluded and directed to their primary care provider for follow-up care. Eligible and interested individuals (n = 223) provided written informed consent before enrolling in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram: Participant Enrollment and Follow-up

Intervention

Group Lifestyle Balance ™ (GLB) is a 12-month, 22-session adaptation of the DPP lifestyle intervention designed for delivery in community settings. The DPP-GLB program [23] is based on social cognitive theory and focuses on behavioral skills (e.g. goal setting, self-monitoring of PA, diet and weight; stimulus control, and problem-solving) to achieve program goals and to support long term behavior change. The DPP-GLB program is a direct adaption of the DPP that has been updated to reflect current dietary and physical activity recommendations, to include transition and maintenance sessions, and to allow for face-to-face group delivery. The curriculum is approved for application to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Diabetes Prevention Recognition Program (NDPRP) [24], which has outlined standards for evidence-based lifestyle interventions. The minimum program goals are 150 min/week moderate intensity PA and 7% WL. Group behavioral support was provided throughout the intervention and participants were encouraged to maintain these minimum goals or establish new personal goals for PA and WL once the minimum goals were met. Initial calorie (1200–2000 kcal/day) and fat (33–55 g/day) goals were assigned based on starting weight and could be modified to support progress and weight loss maintenance. Participants chose weekly face-to-face groups or to view a DVD for each session independently for the first 12 sessions. For participants who chose DVD, individuals watched one session per week and received a weekly telephone/e-mail contact from the lifestyle coach to discuss the session material and provide feedback on progress and behavior change. Participants who chose DVD were invited to attend optional monthly group meetings to support behavior change. The DVD sessions were also used to supplement the face-to-face group sessions when an individual could not attend the group session due to work schedule, travel, illness, etc. Since the DVD did not extend in to the final 10 maintenance sessions, those sessions were delivered as face-to-face groups on a bi-weekly to monthly schedule. Materials were mailed and follow-up telephone/e-mail contact was done for those who were unable to attend a group session. All group sessions and phone/e-mail contacts were facilitated by experienced lifestyle coaches who completed a comprehensive two-day training on the DPP-GLB curriculum and program delivery.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of this study was factors associated with the concurrent achievement of the minimum WL and PA goals at 6 months. The 6-month time point was selected a priori since it corresponds to the timeframe of the original DPP core intervention, which was based on extensive research that indicates most participants who achieve diet and exercise goals will do so within the first six months of behavioral intervention [25]. The secondary outcomes were the factors related to achievement of these goals at 12 and 18 months. Measures were collected by independent assessment staff using a standard protocol as specified.

Demographic characteristics

Participant age, race/ethnicity, smoking history, employment status, and highest education level attained were collected at the screening visit.

Baseline glycemic status

Overnight fasting (8–16 h) venous blood samples were collected. Plasma samples were analyzed (Quest Laboratories, Pittsburgh, PA) for glucose (mg/dL) and HbA1c (%). Participants were categorized as being in the pre-diabetes range if glucose was 100–125 mg/dL and/or HbA1c was 5.7–6.4%.

Weight and height

Participant weight was measured on a digital scale to the nearest tenth of a pound at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months. Participant height was measured at baseline with a stadiometer to the nearest quarter inch. Measured weight and height were used to calculate BMI (kg/m2).

Modifiable activity questionnaire

The interviewer-administered Modifiable Activity Questionnaire (MAQ) was used at baseline, 6, and 12 months to estimate past month leisure PA expressed as metabolic equivalent task (MET) hours per week [26]. The MAQ has been used in epidemiologic studies of adults [27–29], including intervention trials such as the DPP [30]. A cut-point of ≥10 MET-hrs/week was used to estimate ≥150 min/week of moderate intensity PA (4 METs multiplied by 2.5 h/week of brisk walking).

Lifestyle questionnaire

A brief lifestyle questionnaire (LSQ) was developed by the investigators for use in community translation studies and administered at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months at the same time as the weight measurement. The LSQ queried participants about their frequency (days) and duration (minutes) of usual PA, summarized as average minutes of PA during a typical week. The LSQ also asked participants to report the number of days per week (1–7) or per month (<1, 2–3) that they weighed themselves.

Attendance and lifestyle program adherence

Session attendance, phone/e-mail contacts, and completion of weekly self-monitoring records were documented by the lifestyle coach. Session attendance was counted when a participant presented at face-to-face group meetings or completed a telephone/e-mail contact. Maximum attendance was 16 sessions in the first 6 months and 6 sessions in the latter 6 months. Maximum self-monitoring adherence was completion of 23 diet and 20 PA (initiated after session 4) records during the first 6 months and 24 records for each behavior during the latter 6 months.

Statistical analysis

Cumulative ordinal logistic regression models were used to determine the participant baseline demographic and clinical characteristics and program adherence behaviors related to meeting program goals. The outcome of goal achievement was modeled in ordered values of both WL and PA goals, either the PA or WL goal, and neither goal (reference). Odds ratios (OR) and 95% profile likelihood confidence intervals (CI) were generated for each factor in association with goal achievement at 6 months, with probabilities cumulated over lower ordered values. Univariate models were evaluated for violation of the proportional odds assumption across levels of goal achievement. Variables violating the assumption were fit with unequal slopes in the multivariable models. Independent variables with p-value ≤0.25 in the univariate models were selected for inclusion in the multivariate model building process. Spearman rank order correlations were used to detect significant associations (two-sided p < 0.05) between continuous variables (e.g. attendance and self-monitoring records). Independent samples t-tests were used to detect significant differences in mean values of continuous variables between categorical groups (e.g. age and pre-diabetes). When two or more factors were significantly associated, the factor with the strongest univariate association was included in the multivariable models.

Multivariable stepwise logistic regression using the partial proportional odds model [31] was used to determine the factors that were independently associated with lifestyle goal achievement. The probability that a factor entered (p < 0.20) and stayed (p < 0.10) in the model was set a priori. The final model was evaluated by Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and max-rescaled R-square values to determine the appropriateness of the model compared to the intercept only model. To check for consistency, the final multivariable model was built interchanging the significantly associated independent variables. Finally, variables related to lifestyle goal achievement at 12 and 18 months were evaluated using ordinal logistic regression models as described above.

The secondary outcomes, factors related to achievement of each program goal at 6 months, were evaluated using stepwise binary logistic regression models.

The MAQ was used as the primary assessment of PA at 6 and 12 months and the LSQ was used for analysis at all time points. PA levels captured by the MAQ and the LSQ were significantly correlated at 6 and 12 months (Spearman’s rho = 0.57 and 0.59; both p < 0.01). Separate models using the goal approximation of 10 MET-hrs/week from the MAQ and 150 min/week from the LSQ were tested to see if factors associated with goal achievement were similar using the two measures.

Results

Sample characteristics

Study participants (n = 223) were overweight or obese adults [mean weight = 208.8, standard deviation (SD) =41.8 lbs.; BMI = 33.8 (SD = 6.0) kg/m2; age = 58.4 (SD = 11.5) years]. The majority had glucose or HbA1c values in the pre-diabetes range (64.6%), were non-Hispanic White (91.9%), female (62.3%), college educated or higher (63.2%), and worked at least part-time outside the home (65.9%) (Supplemental Table 1). Individuals with blood values in the pre-diabetes range were significantly older compared to those with normal glycaemia [mean = 60.6 (SD = 11.3) vs. 54.3 (SD = 10.7) years; p < 0.01] as were individuals who did not work outside the home compared to those employed full- or part-time [68.5 (SD = 10.1) vs. 53.2 (SD = 8.2) years; p < 0.01]. The median baseline self-reported PA was 7.88 [Interquartile range (IQR) = 2.19, 16.69] MET-hrs/week leisure PA (MAQ) and 120 (IQR = 20, 210 min/week) usual PA (LSQ). With the exception of race/ethnicity, there was adequate variation in measured baseline characteristics to examine each factor in association with program goal achievement.

Sample retention

Sample retention at assessment visits was 91% at 6 months, 85% at 12 months, and 77% at 18 months (Fig. 1). At 12 and 18 months, 43.9% and 45.6% of participants completing assessment visits were aged >60 years, respectively, compared to 26.5% and 26.9% who were aged >60 years among those lost to follow-up at each respective time point. Likewise, 37.0% and 37.4% of participants completing assessment visits at 12 and 18 months, respectively, were not employed outside the home, compared to 17.7% and 23.1% reporting not being employed outside the home at the respective time points. Other baseline characteristics were similar between those who completed study assessments and those lost to follow-up.

Intervention adherence

Participants attended 79% (mean = 12.6, SD = 4.0) of sessions in the first 6 months and 55% (mean = 3.3, SD = 2.4) of sessions in the latter 6 months. On average, 46% of weekly diet records (mean = 10.6, SD = 6.9) and 35% of PA records (mean = 7.0, SD = 6.2) were submitted during the first 6 months. Less than 15% of records were submitted during latter 6 months (mean diet = 3.3, SD = 6.6; mean PA = 3.0, SD = 6.4). Attendance was significantly correlated with self-monitoring behaviors (Spearman’s r ≥ 0.70, p < 0.01).

Intervention outcomes: Weight loss and physical activity at 6, 12, and 18 Months

Improvements in weight and PA were observed during intervention and follow-up (Fig. 2.1, 2.2). Participants lost an average of 11.9 (SD = 11.3) lbs. (5.7% of initial bodyweight) and demonstrated a median increase in PA from baseline to 6 months of 10.88 (IQR = 1.17, 22.64) MET-hrs/week as measured by the MAQ and 57.5 (IQR = 0, 120) min/week based on the LSQ (all; p < 0.0001). Significant weight reduction and increased PA levels were observed at 12 and 18 months compared to baseline. WL was moderately correlated with an increase in usual PA, as measured by the LSQ, at all post-intervention assessment visits (Spearman’s r = 0.15–0.30; all p < 0.05) and with past month leisure PA, as measured by the MAQ, at 12 months (r = 0.26; p < 0.01) with a similar trend at 6 months (r = 0.12; p = 0.09).

Fig. 2.

Changes in 1) Weight and 2) Physical Activity Levels During Intervention (6 and 12 months) and Follow-up (18 months) in a Community Diabetes Prevention Program. Note: p-value for change from baseline: *p < 0.01; **p < 0.0001

A high proportion of participants met at least one of the intervention goals for WL or PA. At 6 months, 82.8% of participants achieved at least one goal and 28.1% met both goals (Fig. 3.1). At 12 months, goal achievement was similar, with 74.7% of participants achieving at least one goal and 29% achieving both goals (Fig. 3.2). At 18 months, 6 months after the intervention ended, the proportion achieving at least one goal decreased to 49.7% (12.4% achieved the WL goal only and 37.3% achieved the PA goal only) and 15.4% of participants achieved both goals.

Fig. 3.

Frequency of Achieving Weight Loss (WL) and Physical Activity (PA) Goals at 1) 6 and 2) 12 Months in a Community Diabetes Prevention Program. *Note: PA goal defined as 10 MET-hours per week (approximately 150 min/week moderate intensity)

Factors associated with achievement of both weight loss and physical activity goals at 6 Months

The baseline demographic and clinical features and lifestyle program adherence characteristics most associated with achieving or exceeding both lifestyle goals (n = 57) compared to achieving neither goal (n = 35) are presented in Fig. 4.1. Baseline glucose or HbA1c values in the pre-diabetes range [Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) = 0.49, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 0.26, 0.91], higher baseline BMI (AOR = 0.89 per unit increase, 95% CI = 0.83, 0.96), and female sex (AOR = 0.52, 95% CI = 0.28, 0.97) were associated with lower odds of goal achievement. Likewise, interchanging age for pre-diabetes in the final model produced an inverse association with goal achievement (AOR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.94, 0.99).

Fig. 4.

Odds Ratio (OR) and Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) Point Estimates and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for Factors Associated with Achieving 1) Both Program Goals (7% Weight Loss and 10 MET-hours per week Physical Activity), 2) the 7% Weight Loss Goal, and 3) the Physical Activity Goal Compared to Participants Who Did Not Achieve Those Program Goals at 6 Months Among Participants in a Community Diabetes Prevention Program (n = 203). a Only effect variables with p ≤ 0.10 in stepwise logistic regression are included in adjusted models. b Glycemic status categorized by baseline fasting glucose and HbA1c values; estimates shown for individuals with values in the pre-diabetes range (glucose 100–125 mg/dL; HbA1c 5.7–6.4%) compared to the reference group of individuals with values in the normal range (glucose <100 mg/dL; HbA1c <5.7%). c Partial proportional odds for achieving one or both goals compared to neither goal. d Partial proportional odds for achieving both goals compared to one or neither goal. *p < 0.05

For program adherence, number of sessions completed (AOR = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.24, 1.82) and self-weighing (AOR = 1.19 per day each week, 95% CI = 1.06, 1.33) were significantly associated with greater odds of goal achievement. Interchanging self-monitoring PA (AOR = 1.18 per record submitted, 95% CI 1.12, 1.26) or diet (AOR = 1.18 per record submitted, 95% CI = 1.12, 1.26) for attendance as the marker of adherence produced similar associations. In addition, completing the assessment visit during the summer season resulted in a significantly greater likelihood of meeting both goals (AOR = 3.47, 95% CI = 1.84, 6.68). Substituting PA measured by the LSQ rather than the MAQ did not substantially change the results.

Factors associated with achievement of either the weight loss or physical activity goal at 6 Months

The factors associated with achieving either the WL or PA goal were similar to those associated with concurrent goal achievement at 6 months (Fig. 4.1). Program adherence factors were more strongly related to WL goal achievement (Fig. 4.2) and conversely baseline participant factors were more strongly related to PA goal achievement (Fig. 4.3), but overall relationships were in the same direction. Other factors that were significantly associated with achieving the PA goal at 6 months included assessment during the summer season (AOR = 7.74, 95% CI = 3.46, 17.33), PA level greater than or equal to the goal at baseline (AOR = 4.83, 95% CI = 1.97, 11.82), and never smoking (AOR = 3.37, 95% CI = 1.49, 7.64).

Factors associated with goal achievement at 12 and 18 Months

In multivariable models, several baseline and program adherence factors were associated with achieving both ≥7% WL and ≥10 MET-hrs/week leisure PA goals at 12 months. These included ≥7% WL at 6 months (AOR = 9.55, 95% CI = 6.51, 21.27), a PA level greater than or equal to the goal at 6 months (AOR = 3.53, 95% CI = 1.59, 8.14), summer season at 12 months (AOR = 3.51, 95% CI = 1.70, 7.56), self-weighing at 12 months (AOR = 1.13 per additional day per week, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.26), total attendance (AOR = 1.10 per session, 95% CI = 1.03, 1.18), and self-monitoring diet (AOR = 1.05 per record submitted, 95% CI = 1.02, 1.08) or PA (AOR = 1.05 per record submitted, 95% CI = 1.02, 1.08). At 18 months, the only significant factors related to achieving both ≥7% WL and ≥150 min/week PA in multivariable models were ≥7% WL at 6 months (AOR = 5.07, 95% CI = 2.60, 10.26) and a PA level greater or equal to the goal at 6 months (AOR = 5.76, 95% CI = 2.56, 13.82).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first DPP translation study to examine a combination of baseline and lifestyle program adherence factors associated with concurrent achievement of recommended weight loss and physical activity goals. Nearly 30% of this community sample met both the minimum 7% WL and 150 min/week PA goals at 6 and 12 months, with about 80% achieving at least one program goal. Results confirmed what has previously been shown in long-term randomized controlled trials; individuals who successfully achieved both lifestyle goals over time were those who attended sessions more frequently and regularly self-monitored weight, diet, and PA compared to those who met neither goal. Findings such as these help to establish benchmarks for significant factors related to program success in community-delivered interventions.

Having a lower starting BMI was significantly associated with greater odds of achieving both WL and PA goals at 6 months, which aligns with findings from clinical trials such as the DPP [9]. In addition, among this large sample of individuals with varying combinations of metabolic syndrome risk factors, those whose baseline glycemic status was in the normal range had 2 times greater odds of achieving both lifestyle intervention goals compared to participants whose glucose and/or HbA1c values were elevated at baseline. If replicated, this finding suggests that more concerted efforts may be needed to engage higher risk individuals in lifestyle programs to aid success in meeting program goals. Further exploration of the impact of other clinical features (e.g. duration of hyperglycemia) on achievement of behavioral goals is needed to increase understanding of the observed relationships.

Participant sex was also associated with lifestyle goal achievement. Women were nearly half as likely as men to achieve both program goals at 6 months. Observations made in the DPP [9] and in the Montana Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes Prevention Program [11] have indicated that women are less likely than men to meet the physical activity goal. The results from this community trial add to the evidence that programs may need to be tailored to help women increase their physical activity levels and achieve desired weight loss.

Markers of intervention adherence were significantly associated with concurrent achievement of lifestyle intervention goals. Participants who were able to achieve both program goals at 6 months were more likely to attend sessions, self-monitor diet and PA, and self-weigh. The DVD option for receiving the first 12 lifestyle sessions likely increased attendance and therefore goal achievement, although the study was not designed to test this relationship directly. These findings reinforce earlier studies that have shown adherence to program behaviors are critical to achieving and maintaining WL and PA goals [9, 32, 33]. Incorporating new strategies into lifestyle programs to promote more frequent diet, PA and weight self-monitoring, such as mobile applications and wearable activity monitors, may provide additional and perhaps more convenient options for participants to track their progress, with potential to enhance success in achieving goals.

In this study, completing the 6-month assessment visit during the summer season was also related to higher odds of achieving both goals and in achieving the PA goal when examined separately. This relationship is supported by our previous evaluation of PA changes among the DPP-GLB participants in which PA level was impacted by season [19]. This finding highlights the need to incorporate strategies into community programming to help individuals increase and maintain PA levels during inclement weather in order to achieve program goals.

Good sample retention and maintenance of clinically meaningful [24, 34] changes in weight and PA at 12 and 18 months enabled us to look at factors related to long-term achievement of goals in this community study. As behavioral therapy became less intensive from 6 to 12 months (i.e. transition from weekly to monthly sessions) and ended at 12 months, we anticipated a diminished proportion of participants maintaining goal achievement. The strongest association with WL and PA success at 12 and 18 months was independent achievement of those same goals at 6 months. This demonstrates the importance and predictive value of early adherence in a lifestyle program, which has been supported by observations from other clinical and community efforts [35–37]. Identifying non-responders early during an intervention is important for targeting supplemental efforts and/or systematically examining new approaches to engage participants in the lifestyle change process, particularly as they enter the second six months of intervention.

The racial and ethnic make-up of the sample (primarily Caucasian) was representative of the communities surrounding the intervention sites. This represents a limitation of the current study and generalizability of conclusions. Community efforts among racially and ethnically diverse populations should further evaluate factors related to success in order to help guide program development. Although our results were consistent with respect to factors related to goal achievement when physical activity was determined from two separate questionnaires, the inherent limitations of using self-report measurements, such as recall and reporting bias, must be acknowledged when interpreting the results.

Conclusions

Diabetes prevention efforts as a whole have been successful in helping individuals make behavioral changes that in turn positively impact health outcomes. An important part of program dissemination is identifying when and with whom public health practitioners can best target diabetes and CVD prevention efforts, given limited resources. This study supports the concept that early adoption and compliance to self-monitoring and self-weighing behaviors are associated with lifestyle success. The study also suggests that higher risk individuals (i.e. those with pre-diabetes) may benefit from additional program support. Thus, dissemination efforts should reinforce early program engagement and consider alternative approaches for those not meeting goals by 6 months, including adding strategies to make monitoring diet and PA more user-friendly and to assist participants in increasing and maintaining PA during inclement weather.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 13 kb)

Compliance with ethical standards

The study protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (now the Human Research Protection Office). Written, informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All procedures and research activities were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board and in compliance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Source of funding

Funding support was provided by the National Institutes of Health through grant number R18 DK081323–04 and grant number T32 CA186783 (postdoctoral training award for Dr. Eaglehouse). The funding agency did not have a role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; and in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Providers should reinforce early adoption of self-regulation behaviors and offer additional program support to those not achieving desired lifestyle goals within the first 6 months.

Policy: Policymakers should consider provision of coverage for healthy lifestyle programs for patients earlier in the diabetes-development process, i.e. when patients present with metabolic syndrome components even in the absence of prediabetes.

Research: Future efforts should evaluate other participant and program characteristics that impact on individual success at achieving weight and physical activity goals.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13142-017-0494-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the Uniter States. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/2014statisticsreport.html.

- 2.Ervin, R.B., Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults 20 years of age and over, by sex, age, race and ethnicity, and body mass index: United States, 2003–2006. Natl Health Stat Report, 2009; (13): p. 1–7. [PubMed]

- 3.Knowler WC, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. New Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuomilehto J, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(18):1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan XR, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The da Qing IGT and diabetes study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(4):537–544. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosaka K, Noda M, Kuzuya T. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: A Japanese trial in IGT males. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2005;67(2):152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whittemore R. A systematic review of the translational research on the diabetes prevention program. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2011;1(3):480–491. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0062-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson M, et al. Can diabetes prevention programmes be translated effectively into real-world settings and still deliver improved outcomes? A synthesis of evidence. Diabetic Medicine. 2013;30(1):3–15. doi: 10.1111/dme.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wing RR, et al. Achieving weight and activity goals among diabetes prevention program lifestyle participants. Obesity Research. 2004;12(9):1426–1434. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wing RR, et al. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(15):1563–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amundson HA, et al. Translating the diabetes prevention program into practice in the general community: Findings from the Montana cardiovascular disease and diabetes prevention program. The Diabetes Educator. 2009;35(2):209–210. doi: 10.1177/0145721709333269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinelli NR, et al. Family support is associated with success in achieving weight loss in a group lifestyle intervention for diabetes prevention in Arab Americans. Ethnicity & Disease. 2011;21(4):480–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whittemore R, et al. Translating the diabetes prevention program to primary care: A pilot study. Nursing Research. 2009;58(1):2–12. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31818fcef3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brokaw SM, et al. Effectiveness of an adapted diabetes prevention program lifestyle intervention in older and younger adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2015;63(6):1067–1074. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamman RF, et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2102–2107. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taradash J, et al. Recruitment for a diabetes prevention program translation effort in a worksite setting. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2015;41c:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer MK, et al. Improving employee health: Evaluation of a worksite lifestyle change program to decrease risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2015;57(3):284–291. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eaglehouse YL, et al. Impact of a community-based lifestyle intervention program on health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 2016;25(8):1903–1912. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1240-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eaglehouse YL, et al. Physical activity levels in a community lifestyle intervention: A randomized trial. Transl J Am Coll Sports Med. 2016;1(5):45–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer, M. K., et al. (2014). Diabetes prevention efforts in the community are effective for older, at-risk adults [abstract]. In: 74th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes. 63(Suppl 1): A1-A102.

- 21.Kerner W, Bruckel J. Definition, classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes. 2014;122(7):384–386. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1366278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grundy SM, et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433–438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramer MK, et al. Translating the diabetes prevention program: A comprehensive model for prevention training and program delivery. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(6):505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diabetes Prevention Recognition Program: Standards and Operating Procedures. Available at www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/recognition.

- 25.Wadden TA, Butryn ML. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 2003;32(4):981–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8529(03)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kriska AM, Caspersen CJ. Introduction to the collection of physical activity questionnaires. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1997;29(6S):S5–S9. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199706001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kriska AM, et al. Development of questionnaire to examine relationship of physical activity and diabetes in pima Indians. Diabetes Care. 1990;13(4):401–411. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Momenan AA, et al. Reliability and validity of the Modifiable activity questionnaire (MAQ) in an Iranian urban adult population. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2012;15(5):279–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pettee Gabriel K, et al. Reliability and convergent validity of the past-week Modifiable activity questionnaire. Public Health Nutrition. 2011;14(3):435–442. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kriska AM, et al. Physical activity in individuals at risk for diabetes: Diabetes prevention program. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2006;38(5):826–832. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000218138.91812.f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterson BL, Harrell FE. Partial proportional odds models for ordinal response variables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1990;Series B(39):205–217. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wing RR, Hill JO. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2001;21:323–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butryn ML, et al. Consistent self-monitoring of weight: A key component of successful weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(12):3091–3096. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williamson DA, Bray GA, Ryan DH. Is 5% weight loss a satisfactory criterion to define clinically significant weight loss? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23(12):2319–2320. doi: 10.1002/oby.21358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unick JL, et al. Evaluation of early weight loss thresholds for identifying nonresponders to an intensive lifestyle intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22(7):1608–1616. doi: 10.1002/oby.20777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unick JL, et al. Weight change in the first 2 months of a lifestyle intervention predicts weight changes 8 years later. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23(7):1353–1356. doi: 10.1002/oby.21112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller CK, Nagaraja HN, Weinhold KR. Early weight-loss success identifies nonresponders after a lifestyle intervention in a worksite diabetes prevention trial. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2015;115(9):1464–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 13 kb)