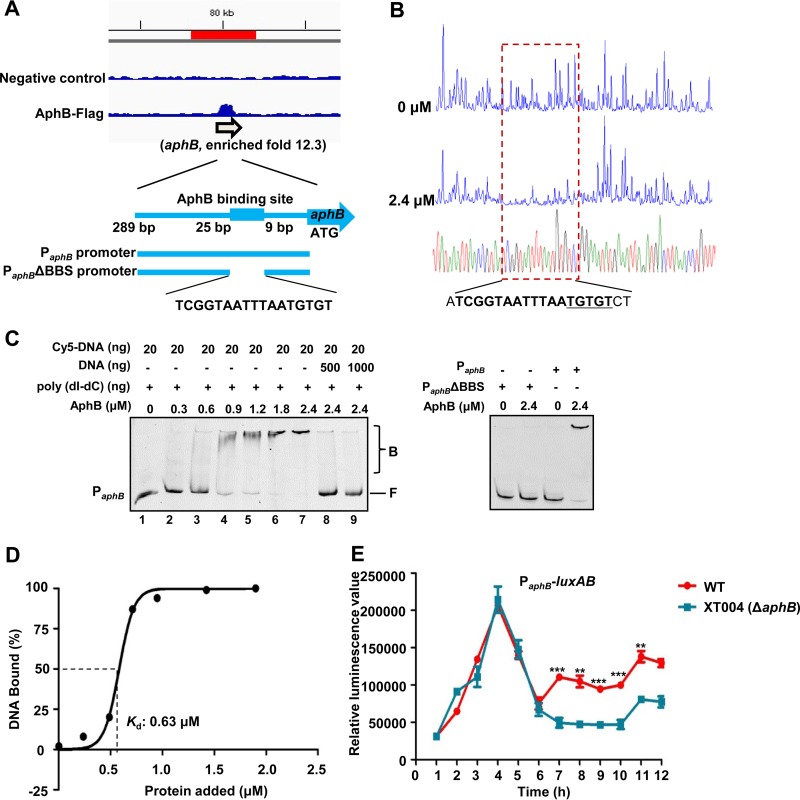

FIG 4.

AphB binding directly to its own promoter for self-activation. (A) AphB binding to its own promoter region, as illustrated by the peak (enriched 12.3-fold) identified in the ChIP-seq experiment. The AphB-binding site and the probes used for the EMSA studies shown in panel C are illustrated. (B) DNase I footprinting analysis of AphB binding to the aphB promoter. Electropherograms, after DNase I digestion, of the aphB promoter probe (200 ng) incubated with 0 or 2.4 μM AphB are shown. The imperfect dyad of the binding site (TGTGT) is underlined. (C) EMSA of the aphB promoter region (PaphB) (left) and PaphBΔBBS (right) with purified AphB. Twenty nanograms of each Cy5-labeled probe was added to the EMSA reaction mixtures. A 10-fold excess of nonspecific competitor DNA [poly(dI-dC)] was added to the EMSA reaction mixtures. A 25- or 50-fold excess of unlabeled specific competitor DNA was also included (left, lanes 8 and 9). AphB-bound (labeled B) or unbound (labeled F) DNA is shown. (D) Plot showing the affinity of AphB binding to its own promoter. The densitometric intensities of bound DNA fragments are plotted against the AphB concentrations. The concentration of AphB causing half-maximal binding (Kd) is shown. A representative plot is shown (n = 3). (E) PaphB-luxAB transcriptional analysis in wt and XT004 (ΔaphB) strains. The wt and XT004 strains carrying the PaphB-luxAB reporter plasmid were cultured in LBS medium for 12 h and assayed for luminescence every 1 h. The results are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005, Student's t test, relative to the wt strain.