Abstract

Background

Approximately 30% of patients with Crohn disease (CD) are unresponsive to biologics. No previous study has focused on a plant-based diet in an induction phase of CD treatment.

Objective

To investigate the remission rate of infliximab combined with a plant-based diet as first-line (IPF) therapy for CD.

Methods

This was a prospective single-group trial conducted at tertiary hospitals. Subjects included consecutive adults with a new diagnosis (n = 26), children with a new diagnosis (n = 11), and relapsing adults (n = 9) with CD who were naïve to treatment with biologics. Patients were admitted and administered a standard induction therapy with infliximab (5 mg/kg; 3 infusions at 0, 2, and 6 weeks). Additionally, they received a lacto-ovo-semivegetarian diet. The primary end point was remission, defined as the disappearance of active CD symptoms at week 6. Secondary end points were Crohn Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score, C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration, and mucosal healing.

Results

Two adults with a new diagnosis were withdrawn from the treatment protocol because of intestinal obstruction. The remission rates by the intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were 96% (44/46) and 100% (44/44), respectively. Mean CDAI score (314) on admission decreased to 63 at week 6 (p < 0.0001). Mean CRP level on admission (5.3 mg/dL) decreased to 0.2 (p < 0.0001). Mucosal healing was achieved in 46% (19/41) of cases.

Conclusion

IPF therapy can induce remission in most patients with CD who are naïve to biologics regardless of age or whether they have a new diagnosis or relapse.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are increasing as the condition expands into new regions; consequently, IBD is now a global disease.1

Newly introduced biologics have revolutionized the treatment of various conditions, including malignant neoplasms, autoimmune diseases, and others.2–4 Infliximab and adalimumab are monoclonal antitumor necrosis factor α antibodies that were introduced for IBD treatment and have effectively induced and maintained remission in Crohn disease (CD).5–11 Therapy with biologics has popularized the concept of mucosal healing for IBD treatment.12,13

IBD is a polygenic disease triggered by environmental factors.14 Despite the recognition that Westernization of lifestyle is a major IBD driver,15,16 no countermeasures have been recommended against such lifestyle changes with the exception of nonsmoking for patients with CD.17 Gut microflora may be the main environmental factor responsible for IBD18; further, diet influences gut microflora.19,20

IBD is prevalent in wealthy nations in which dietary Westernization has occurred.21 Dietary Westernization is characterized by increased consumption of animal protein, animal fat, and sugar, with decreased consumption of grains. A consistent risk factor for IBD is the consumption of meat22–26 and sweets,24–26 whereas a preventive factor is the consumption of vegetables and fruits.22,27 Consequently, we recognize from our clinical experience that IBD is highly associated with lifestyle and that it is mainly mediated by a Westernized diet. Additionally, diet-associated dysbiosis of the gut microflora seems to be the most relevant environmental factor in IBD.18 Therefore, restoring and maintaining gut symbiosis with an adequate diet is fundamental for IBD treatment. We designed a semivegetarian diet (SVD), a type of plant-based diet (PBD), as therapy for IBD.28 Since 2003, we have served the PBD to all inpatients with IBD at our center and found that PBD prevented CD relapse28 and induced remission without medication in a subset of patients with mild ulcerative colitis.29,30

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (US Department of Agriculture [USDA] Food Pattern) and dietary guidelines for chronic common diseases consistently recommend increased consumption of vegetables and fruits and decreased consumption of meats, processed meats and added sugars.31,32 PBDs are listed as variations of USDA healthy eating patterns.31 Epidemiologic studies provide convincing evidence that individuals who consume PBDs experience improved longevity and are less affected by common chronic diseases than those who eat omnivorous diets.33,34

Ideal treatment involves early commencement of therapy before irreversible damage occurs, namely during the window of opportunity.35 This concept has been validated in rheumatoid arthritis treatment.36–38 Current guidelines for CD limit the use of infliximab or adalimumab for patients who are unresponsive to conventional therapy.17

The natural history of CD usually is characterized by a disabling course; 10% to 15% of patients are relapse-free for the rest of their lives, however.39–41 The current remission rate in CD with early use of infliximab is 64%.8 This indicates that 30% to 40% of patients, even those treated early with infliximab, are likely to experience a disabling disease course after their first treatment. Reliable induction of remission is the first step toward improving the natural history of CD.

Our goal is a drastic enhancement of the relapse-free rate in CD—namely, induction of remission by incorporating three recently developed concepts in medicine (biologics, PBD, and window of opportunity), followed by maintenance of remission with a PBD rather than further use of biologics with or without immunosuppressants. We hypothesized that these modalities could enhance the relapse-free rate.

We designed the present trial to determine whether infliximab combined with a PBD as first-line (IPF) therapy could enhance the remission rate for patients with CD.

METHODS

Design and Settings

We designed a single-group, nonrandomized, open noncontrolled trial that was conducted at Nakadori General Hospital and Akita City Hospital, tertiary care facilities in northern Japan. The first author, MC, worked for the former facility between 2003 and 2012 and Akita City Hospital since 2013.

Patients

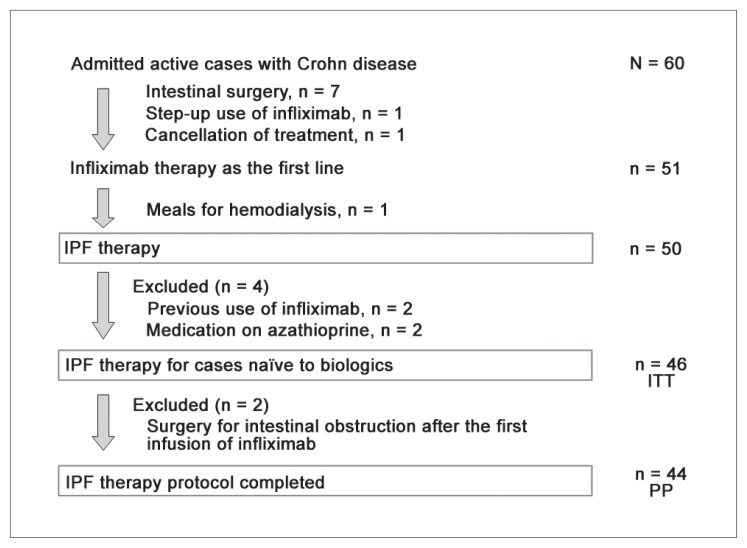

All patients with active symptom(s) regardless of their Crohn Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score42 were advised to undergo hospitalization for potential IPF therapy. Between August 2003 and December 2015, 60 patients with active CD were admitted to the hospital (Figure 1). Subjects were tested for tuberculosis or hepatitis B infection43; no patient had a positive result. Patients previously treated with biologics or those taking prednisolone or azathioprine, which influence IPF efficacy, were excluded. Patients prescribed a partial elemental diet or 5-aminosalicylic acid were included.

Figure 1.

Enrollment of inpatients with active Crohn disease for IPF therapy.

IPF therapy = infliximab and plant-based diet as first-line therapy; ITT = intention to treat; PP = per protocol.

Protocol: IPF Therapy

The protocol involved standard induction therapy with infliximab combined with an SVD.28 Briefly, metronidazole 750 mg/d was administered after admission. Patients received a liquid infusion without meals during morphologic studies to assess clinical types and intestinal stenosis. Liquid infusion duration varied from 3 to 7 days depending on the extent of previous outpatient morphologic studies before admission. Infliximab (5 mg/kg) was infused at weeks 0, 2, and 6.11 The PBD, which was initiated on the same day of the infusion, was a lacto-ovo-semivegetarian diet that included fish once a week and meat once every 2 weeks. Calories were gradually increased to a maximum of about 30 kcal per kg standard body weight. After about 1 month, metronidazole was switched to 5-aminosalicylic acids. After the third infusion of infliximab, patients were discharged. Patients who could not be admitted for the entire induction phase were discharged after the second infliximab infusion and readmitted for the third infusion.

IPF Therapy Efficacy

The primary end point was clinical remission at week 6 after the first infliximab infusion. Clinical remission was defined as the absence of active symptoms. Remission was assessed by the attending physician (MC). Secondary end points were normalization of C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration at week 6 and mucosal healing. CDAI also was evaluated. Patients were morphologically studied with colonoscopy and/or contrast barium enema before discharge. In this study, mucosal healing was defined as the absence of active findings of CD such as ulcer, aphthoid lesions, edema, redness, and bleeding. Symptoms and CDAI were evaluated before and after infliximab therapy up to week 6.

Safety Evaluations

Vital signs, patient reports, findings during daily practitioner rounds, physical examinations, and weekly laboratory test findings were assessed to ensure safety.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate differences of therapeutic effects among adults with a new diagnosis, children with a new diagnosis, and relapsed adults, the rates of remission, normalization of CRP concentration, and mucosal healing were assessed with a χ2 test. CDAI score and CRP concentration were expressed as the mean plus or minus the standard deviation and median (interquartile range). To evaluate effects of treatment on CDAI and CRP, differences were first analyzed by repeated analysis of variance (ANOVA). If ANOVA results were statistically significant, data were analyzed using the post hoc Tukey-Kramer honestly significant difference test. A p value of 0.05 or lower indicated a statistically significant difference. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP 8 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Ethical Considerations

For patients with strictures,44 infliximab therapy poses risk for intestinal obstruction,45–47 and the need for potential surgery was discussed. This protocol and the template informed consent forms were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of Nakadori General Hospital and the Ethical Committee of Akita City Hospital (Protocol number 19–2003, 12–2013, 15–2015). The primary author/investigator (MC) obtained informed consent from all patients.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Among 60 patients with active CD, 7 were indicated for intestinal surgery (Figure 1). Infliximab was used as a step-up approach for 1 patient. One patient cancelled medical treatment, and another patient on hemodialysis underwent standard first-line infliximab therapy; in that scenario, the patient required a diet for hemodialysis instead of a PBD. IPF therapy was administered to the remaining 50 patients. Two patients previously treated with infliximab and 2 patients receiving azathioprine were excluded. Forty-six patients who were naïve to biologics comprised the intention-to-treat subset and underwent IPF therapy. However, 2 patients with a new diagnosis (both men aged 21 years with stricture-type disease) developed intestinal obstruction after the first infusion of infliximab and underwent surgery. The 44 patients who completed the protocol (Figure 1) included 24 adults with a new diagnosis, 11 children ages 18 years and younger with a new diagnosis, and 9 relapsing adults. The demographic characteristics of our 44 patients are presented in Table 1. The mean disease duration for relapsing adults (92.8 months) was longer than the mean for adults with a new diagnosis (8.8 months) or the mean for children (12.7 months). More than 50% of patients in all groups had 1 or more perianal fistula(s) that were draining pus and/or anal tag(s). Five of 33 (15%) adults were smokers who stopped smoking after their admission. Eight patients had a CDAI score lower than 150 (quiescent stage); 7 had a score of 150 to 220 (mild-moderate); 19 scored 220 to 450 (moderate-severe); and 10 patients had a score higher than 450 (severe/fulminant).44 Three relapsing adults were on partial elemental diet: 600, 900, and 1200 kcal/d, respectively. The same elemental diet was maintained during the first half of hospitalizations and was decreased by 300 kcal during the latter half of hospitalizations, while the amount of PBD was increased. Five patients were discharged after the second infliximab infusion and were readmitted for the third infusion. Sixteen of 44 patients in the present protocol also were described in a 2010 paper.28

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | Total | New diagnosis | Relapsed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Childrena | Adults | ||

| Number of patients | 44 | 24 | 11 | 9 |

| Male/female | 29/15 | 15/9 | 9/2 | 5/4 |

| Age (y) | ||||

| Range | 13–77 | 19–61 | 13–18 | 21–77 |

| Mean ± SD | 27.2 ± 13.7 | 30.0 ± 11.9 | 15.9 ± 1.8 | 33.6 ± 18.8 |

| Median (IQR) | 22.0 (18.3–30.8) | 27.5 (21.0–35.0) | 16.0 (15.0–17.0) | 24.0 (21.5–43.5) |

| Disease duration (mo) | ||||

| Range | 1–240 | 1–39 | 1–60 | 22–240 |

| Mean ± SD | 26.9 ± 45.1 | 8.8 ± 10.6 | 12.7 ± 17.2 | 92.8 ± 64.1 |

| Median (IQR) | 8.0 (3.0–33.3) | 4.5 (2.0–11.5) | 6.0 (3.0–18.0) | 72.0 (57.0–122.5) |

| Location of lesion | ||||

| L1 Ileal | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| L2 Colonic | 13 | 8 | 2 | 3 |

| L3 Ileocolonic | 30 | 15 | 9 | 6 |

| L4 Isolated upper lesions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Behavior | ||||

| B1 Nonstricturing, nonpenetrating | 33 | 18 | 10 | 5 |

| B2 Stricturing | 11 | 6 | 1 | 4 |

| B3 Penetrating | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Perianal disease modifier | 31 | 16 | 10 | 5 |

| Anal fistula | 24 | 11 | 9 | 4 |

| Anal skin tag | 13 | 8 | 3 | 2 |

| Current smoker | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Previous segmental resection | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| CDAI score | ||||

| Range | 52–834 | 52–834 | 144–472 | 88–679 |

| Mean ± SD | 314 ± 188 | 348 ± 214 | 270 ± 97 | 279 ± 200 |

| Median (IQR) | 270 (177–357) | 296 (195–547) | 278 (157–322) | 225 (130–404) |

| < 150 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| 150–220 mild-moderate | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 220–450 moderate-severe | 19 | 9 | 7 | 3 |

| > 450 severe/fulminant | 10 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| C-reactive protein concentration (mg/dL) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 5.4 ± 4.9 | 5.4 ± 5.9 | 5.2 ± 3.5 | 5.6 ± 3.9 |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (1.6–7.5) | 2.8 (1.2–7.1) | 4.4 (2.4–8.6) | 5.9 (2.8–7.4) |

Children = 18 years of age or younger.

CDAI = Crohn Disease Activity Index; IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

Efficacy

The primary end point was remission. Two patients were withdrawn from the protocol because of intestinal obstruction. All remaining patients reported considerable improvement 1 week after the first infliximab infusion. Most patients had no symptoms between weeks 1 and 3. A CDAI score lower than 150 indicates remission in many studies.42 The rate of CDAI scores lower than 150 among patients with baseline CDAI scores higher than 150 was 50% (18/36), 69% (25/36), 86% (30/35), 94% (31/33), 94% (31/33), and 100% (36/36) at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively. Among patients with draining perianal fistulas, 24 experienced fistula closure within weeks 1 and 3. All 44 patients who completed the protocol achieved remission at week 6. Remission rates by intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis were 96% and 100%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rates of remission and normalization of C-reactive protein concentration and mucosal healing at week 6 after infliximab and a plant-based diet as first-line therapy

| Subjects | N | Remission | CRP concentration | Mucosal healing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 46 | 96% (44/46) ITT, 100% (44/44) PP | 84% (37/44) | 46% (19/41) |

| Adults, new diagnosis | 24 | 92% (24/26)a ITT, 100% (24/24) PP | 92% (22/24)b | 38% (9/24)c |

| Children, new diagnosis | 11 | 100% (11/11)a ITT | 82% (9/11)b | 60% (6/10)c |

| Relapsed adults | 9 | 100% (9/9)a ITT | 67% (6/9)b | 57% (4/7)c |

p value for comparison among the three groups (χ2 test) = 0.3085.

p value for comparison among the three groups (χ2 test) = 0.2344.

p value for comparison among the three groups (χ2 test) = 0.3980.

CRP = C-reactive protein; ITT = intention to treat; PP = per protocol.

Secondary End Points

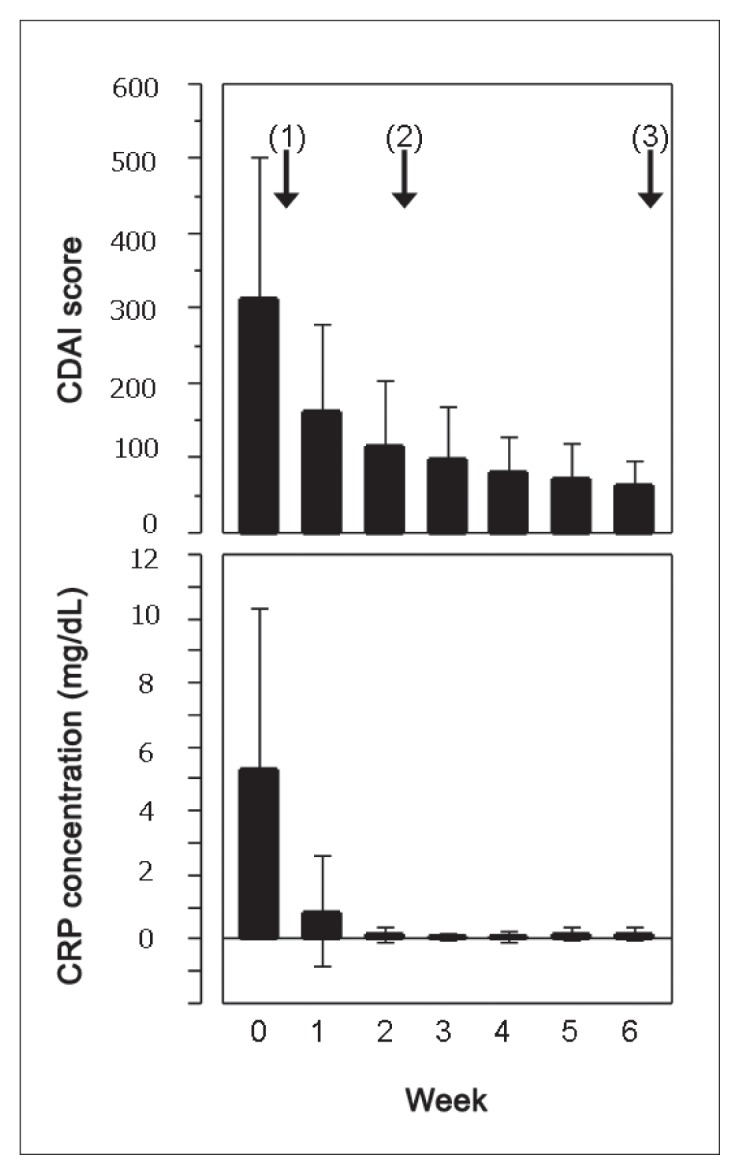

The mean CDAI score was significantly decreased from 314 before IPF therapy to 163 after the first infliximab infusion (p < 0.0001). The scores were further decreased chronologically: 115, 98, 82, 74, and 63 at weeks 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively (Table 3, Figure 2). Chronologic CDAI score changes were similar among the 3 groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

CDAI score and CRP concentration changes during induction phase after IPF therapy

| Subjects | Number of patients | Weeks after IPF therapy (mean ± SD) | p value (ANOVA) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||

| CDAI score | |||||||||

| Total | 44 | 314 ±189 | 163 ± 116 | 115 ± 89 | 98 ± 70 | 82 ± 45 | 74 ± 45 | 63 ± 32 | < 0.0001 |

| Adults, new diagnosisa | 24 | 348 ± 214 | 171 ± 141 | 121 ± 104 | 93 ± 73 | 76 ± 50 | 65 ± 44 | 57 ± 30 | < 0.0001 |

| Children, new diagnosisa | 11 | 270 ± 97 | 145 ± 76 | 108 ± 78 | 112 ± 86 | 84 ± 37 | 89 ± 52 | 71 ± 35 | < 0.0001 |

| Relapsed adultsa | 9 | 279 ± 200 | 162 ± 87 | 109 ± 58 | 99 ± 40 | 93 ± 38 | 78 ± 38 | 69 ± 35 | < 0.0001 |

| CRP concentration (mg/dL) (normal ≤ 0.3) | |||||||||

| Total | 44 | 5.3 ± 5.0 | 0.9 ± 1.7 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Adults, new diagnosisb | 24 | 5.7 ± 5.9 | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Children, new diagnosisb | 11 | 5.2 ± 3.5 | 1.1 ± 2.8 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Relapsed adultsb | 9 | 5.6 ± 3.9 | 0.8 ± 0.7 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | < 0.0001 |

p value for comparison among three groups (ANOVA) = 0.7949.

p value for comparison among three groups (ANOVA) = 0.9263.

ANOVA = analysis of variance; CDAI = Crohn Disease Activity Index; CRP = C-reactive protein; IPF therapy = infliximab and a plant-based diet as first-line therapy; SD = standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Change of CDAI score (upper panel) and CRP concentration (lower panel) before and after IPF therapy in 44 patients with CD. The solid bar denotes the mean and the thin line shows the standard deviation. Arrows with numbers in brackets indicate 3 infliximab infusions at weeks 0, 2, and 6. CDAI score and CRP concentration (mg/dL) (reference range ≤ 0.3) are presented in Table 3. All CDAI scores and CRP concentrations significantly decreased after IPF (analysis of variance p < 0.0001, Tukey-Kramer honestly significant difference test p < 0.0001).

CD = Crohn disease; CDAI = Crohn Disease Activity Index; CRP = C-reactive protein; IPF therapy = infliximab and a plant-based diet as first-line therapy.

The mean CRP concentration decreased from 5.3 mg/dL before IPF therapy to 0.9 mg/dL after the first infliximab infusion (p < 0.0001). The CRP concentration (reference range, ≤ 0.3 mg/dL) was within defined limits (0.2 mg/dL) at week 2 and thereafter (Table 3, Figure 2). The chronologic CRP concentration changes were similar among the 3 groups (Table 3). Among adults with a new diagnosis, CRP concentrations from weeks 2 to 6 remained stable (0.1 mg/dL). However, CRP concentration fluctuated within the reference range for the other 2 groups. The lowest concentration was 0 mg/dL at week 4 and 0.2 mg/dL at week 5 among children with a new diagnosis, and 0.1 mg/dL at week 3 and 0.2 mg/dL at week 4 among relapsing adults (Table 3). The rates of CRP normalization at week 6 were highest (92% [22/24]) among adults with a new diagnosis; intermediate (82% [9/11]) among children with a new diagnosis; and lowest (67% [6/9]) among relapsing adults, although the difference was nonsignificant (p = 0.2344) (Table 2). Normal CRP concentration was achieved by week 5 for 6 of 7 patients with abnormal CRP concentrations at week 6.

Three patients did not undergo morphologic assessment before discharge. Mucosal healing was achieved for 19 of 41 patients (46%) (Table 2).

Safety

Two patients were withdrawn from the protocol because of intestinal obstruction. Infusion reactions to infliximab were observed in two patients (eruptions with itching and vomiting). One child with a new diagnosis developed herpes zoster three weeks after completing IPF therapy. Metronidazole was withdrawn because of paresthesia (three patients) and leukocytopenia (one patient). 5-aminosalicylic acid was withdrawn because of mild pancreatitis (two patients), alanine aminotransferase elevation (one patient), and epigastralgia (one patient). All patients ate the PBD, and none experienced an adverse effect such as gaseous distress, abdominal discomfort, or diarrhea.

DISCUSSION

On the basis of the etiopathogenesis of IBD, we designed a PBD as a therapeutic diet for IBD.28 To drastically improve the relapse-free rate associated with CD, the first step involves safe and reliable remission induction with initial treatment. Our study showed that IPF therapy can induce remission for most patients with CD regardless of age or new diagnosis or relapse status.

The CD population (Table 1) in this study reflects Japan’s epidemiology. Male predominance is an Asian (including Japanese) characteristic related to CD.48,49

Clinical remission is far more important than clinical response in practice (the remission rate is lower than the response rate). In this study, the primary end point was induction of remission at week 6. Remission rates reported with infliximab or adalimumab are presented in Table 4.5–10,50–52 In most of the studies reported, subjects had moderate to severe CD (CDAI 220–450),42 but these studies did not include less severe (CDAI score < 220) or more severe (CDAI > 450) cases.5–10,50,51 Our study, however, included cases involving all severity levels. Most patients with CD will experience a disabling course,39–41 and even patients with mild CD experience relapse rates of 60% to 70% in a year.53 Additionally, there is no way to predict which patients will have a disabling or relapse-free course.39–41 If we attempt to improve the natural course of all patients with CD, we must study all patients with active CD regardless of severity. In this study, even if mild cases (CDAI score lower than 220 [n = 15]) were excluded, all 29 patients with CDAI scores higher than 220, including the 10 patients with severe/fulminant disease, achieved remission.

Table 4.

Literature review: Induction of remission in Crohn disease

| Author | Subjects | Regimen | Outcomes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria/scores | Number of patients | CDAI score | CRP concentration (mg/dL) | Duration of disease | Current smoker, % (no.) | Time of assessment | Remission rate (CDAI score < 150 unless otherwise specified), % (no.) | ||

| Targan et al, 19975 | CDAI 220–400 | 27 | Mean 312 | Mean 2.2 | Mean 12.5 y | nd | IFX 5 mg/kg, single infusion | Wk 4 | 48.1 (13/27) |

| Mayer et al, 20016 | CDAI 220–400 | 385 | Median 297 | Median 0.8 | Median 7.9 y | nd | IFX standard | Wk 6 | 38.4 |

| Hyams et al, 20077 | Moderate to severea Children, PCDAI > 30 |

112 | Mean PCDAI 41 | nd | Median 1.6 y | Unlikely | IFX standard and immuno-suppressant | Wk 10 | 58.9 (66/112) |

| D’Haens et al, 20088 | CDAI > 200, age ≥ 16 New diagnosis |

67 | Mean 330 | Median 1.9 | Median 2.0 wk from diagnosis | 43 (28/65) | IFX standard and AZA | Wk 14 | 64 (42/65) |

| Colombel et al, 201050 | Moderate to severea (Naïve to anti-TNF, AZA) |

169 | Mean 290 | Median 1.0 | Median 2.2 y | nd | IFX standard | Wk 6 | 30 (50/169) |

| 169 | Median 2.2 y | IFX standard and AZA | 33 (55/169) | ||||||

| Hanauer et al, 20069 | Moderate to severea Naïve to anti-TNF |

76 | Mean 295 | Mean 1.4 Median 0.9 |

nd | 42 (32/76) | Adalimumab standard | Wk 4 | 36 (27/76) |

| Sandborn et al, 200710 | Moderate to severea Previous IFX |

159 | Mean 313 | Mean 1.9 Median 0.9 |

nd | 35 (55/159) | Adalimumab standard | Wk 4 | 21 (34/159) |

| Watanabe et al, 201251 | Moderate to severe,a Japanese | 33 | Mean 301 | Mean 2.2 | Mean 11.0 y | nd | Adalimumab standard | Wk 4 | 33 (11/33) |

| Naïve to anti-TNF | 14 | 43 (6/14) | |||||||

| Previous anti-TNF | 19 | 26 (5/19) | |||||||

| Miyoshi et al, 201452 | Active, Japanese | 45 | Median HBI 6.5 |

Median 1.3 | Median 8.0 y | nd | Adalimumab standard | Wk 4 | 62 (28/45)b |

| 12 | ≤ 3 y | 92 (11/12) | |||||||

| 33 | > 3 y | 52 (17/33) | |||||||

| Present study | Active, Japanese (Naïve to anti-TNF) | 44 | Mean 314 Median 270 |

Mean 5.4 Median 4.0 |

Mean 26.9 mo Median 8.0 mo |

11 (5/44) | IPF therapy | Wk 6 | Clinical remission 96 (44/46) ITT 100 (44/44) PP |

Moderate to severe, CDAI 220–450.

Harvey-Bradshaw index ≤ 4.

Adalimumab standard = adalimumab 160/80 mg at weeks 0 and 2; AZA = azathioprine; CDAI = Crohn Disease Activity Index; CRP = C-reactive protein; HBI = Harvey-Bradshaw index; IFX = infliximab; IFX standard = infliximab 5 mg/kg at weeks 0/2/6; IPF therapy = infliximab and a plant-based diet as first-line therapy; ITT = intention to treat; nd = not described; PCDAI = pediatric Crohn Disease Activity Index; PP = per protocol; TNF = tumor nectrotizing factor.

Patients who are naïve to biologics and those receiving infliximab combined with azathioprine achieved a higher remission rate with early use of biologics and had a better prognosis than those who began treatment at a later phase or those previously exposed to a biologic or infliximab alone.8,50–52,54 One group of investigators evaluated remission rates under these conditions (early use of infliximab combined with azathioprine in biologics-naïve patients) by using a top-down approach; their patients achieved a remission rate of 64% at week 14.8 So far, that is the highest remission rate reported for a large series (Table 4), demonstrating that 30% to 40% of patients with CD are nonresponders (primary nonresponders) to infliximab. As a result, many studies have been conducted to evaluate response predictors and primary nonresponders.55–58 In our study, even though we included relapsed patients with a median disease duration of 6 years, all our patients achieved remission with IPF therapy. Therefore, disease duration of several years does not seem to be a critical factor for the induction of remission with IPF therapy. Our data show that most patients with CD who are naïve to biologics achieve remission with IPF therapy. Consequently, nonresponse to biologics seems to reflect the therapeutic modality chosen. Several factors may be involved in the successful induction of remission in our studies.

First, all patients in this study were admitted during IPF therapy. Although clinical remission could be obtained in a subset of patients after the first infusion of infliximab,5 we considered that a certain period is needed for the recovery of morphologic changes in the intestine. Consequently, 3 inductive infusions of infliximab were given in 6 weeks11 while patients were hospitalized. However, mucosal healing was achieved only for 46% of patients (Table 2).

Patients’ experience with a PBD, physician knowledge about IBD etiopathogenesis, and dietary guidance regarding PBD from a registered dietitian during hospitalization helped to ensure smooth PBD transitions from hospitals to homes after patient discharge. We confirmed a significantly higher PBD score (mean 25.0), indicating a higher adherence to a PBD59 when compared with the mean base score of 6.4 in 24 patients with CD at approximately 6 years after discharge (p = 0.0131) (unpublished observation).

Hospitalization promotes smoking cessation, and smoking is prohibited in most hospitals in Japan. In our sample, 11% of patients (5/44) were smokers until admission, at which time they quit smoking; thus, all patients were considered nonsmokers. Smoking is a deteriorating factor in CD.60,61 In other studies, the current smoking rate was as high as 43% (Table 4).8–10 Hospitalization duration in our study was shorter than duration for a conventional elemental diet therapy in Japan, for which more than 6 weeks is required.62

PBD was initiated on the same day as the infliximab infusion and was provided throughout hospitalization. We previously reported the efficacy of PBD in preventing relapse in CD.28 In the current study, all patients who completed the protocol achieved remission. Altogether, these findings indicate that PBD is effective during the active and quiescent CD stages.

Preventive factors for IBD (eating vegetables and fruits)22,27 are recommended, and risk factors (eating meat and sweets)22–26 are moderated; indeed, a PBD includes these preventive recommendations and risk moderating factors. Considering that the most important environmental factor in IBD is diet-associated gut microflora,18 we hypothesized that an adequate diet is the basis for IBD treatment during both active and quiescent stages. On the basis of our results, a PBD is recommended for patients with IBD. To date, most studies evaluating induction of remission or prognosis have not devoted resources to diet during treatment. Omnivorous and conventional low-residue diets might reduce the efficacy of biologics.

Metronidazole was used during the first half of hospitalization and is effective in CD with or without perianal fistulas.63,64 An antibiotic is used during the active stage to eliminate potentially pathogenic bacteria in the intestine.65

Clinicians strive to provide the best therapy on the basis of their experience; as a result of our 30-plus years’ experience in treating CD, IPF became routine therapy for CD in 2003 when infliximab was introduced in Japan. The therapeutic approach we propose is comprehensive, and we consider that all factors are necessary for induction of remission, although the contribution of each factor varies. This is the first study in which close attention was paid to diet during induction treatment of CD. In the absence of a control diet, the efficacy of PBD for induction of remission could not be demonstrated. It appears, however, that a PBD plus infliximab was a major contributor to our study’s success.

The Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan designated ulcerative colitis and CD as intractable diseases. Patients with intractable diseases are provided with public medical aid on registration at the Public Health Office, so physicians in Japan are able to provide the best treatments for patients with IBD with less concern about medical expenses. Therefore, its immediate applicability in other countries may be limited.

IPF therapy, which can induce remission for most patients with CD, offers several advantages over the current induction therapy. No serious adverse events occurred with IPF therapy. The rapid efficacy of infliximab enabled patients to eat dinner on the same day of infliximab treatment. Mean CDAI scores at baseline and weeks 1, 2, and 4 in patients treated with adalimumab were 313, 264, 232, and 226, respectively.9 In contrast, patients treated with IPF therapy had mean CDAI scores of 314, 163, 115, and 82, respectively (Table 3, Figure 2). With IPF therapy, the mean CDAI score was 115 as early as week 2, which is lower than the cutoff score of 150 that is recognized as denoting remission.42

The main disadvantage associated with IPF therapy is that hospitalization is required. However, most of our patients who were dealing with chronic symptoms recognized that they needed treatment and accepted hospitalization. There is risk for intestinal obstruction after infliximab treatment.45–47 Infliximab is thought to be effective for inflammatory stenosis and ineffective for fibrotic stricture,66 but it is difficult to distinguish between inflammatory and fibrotic stricture.67 In the absence of signs of obstruction, stricture per se is no longer regarded as a contraindication for infliximab therapy; patients still are regarded as reasonable candidates.66,68 In this study, intestinal obstruction developed within two weeks after the first infliximab infusion for two patients. There is scant literature about early obstruction after infliximab treatment.45–47 We speculate that infliximab is so swiftly effective in ulcer healing69 that the healing process further narrows the stenotic site, resulting in intestinal obstruction. If obstruction is a result of infliximab efficacy, an obstruction could also occur in CD with stricture. When obstruction occurs, it can be immediately diagnosed and surgically treated because patients are in a hospital. We fully inform patients with stricture about intestinal obstruction risk. Apart from two IPF study withdrawals attributable to intestinal obstruction, there were no other withdrawals.

Our study had limitations. There was no control group, and the sample size was small. Nevertheless, we expect that large, controlled studies will be conducted to validate these results.

IPF therapy can induce remission for most patients with CD. Further study is required to determine how remission can be maintained in the long term. Normal CRP concentration is a good indicator of lasting remission, but CRP concentration outside of defined limits is a sign of forthcoming relapse.59,70 Most adults in our study with a new diagnosis (92%) had a normal CRP concentration at week 6, as did children with a new diagnosis (82%) and relapsing adults (67%) (Table 2). About 50% of patients with newly diagnosed adult CD maintained long-term remission with a PBD without periodic maintenance infliximab therapy (the remission rate at 3 to 7 years was 58%, according to Kaplan-Meier analysis [unpublished observation]). Conversely, children and relapsing adults treated with PBD alone tended to relapse within 2 years. Out of 11 children and 9 relapsed adults, 9 and 4 patients experienced relapse, respectively (unpublished observation). IPF therapy should be provided to adults with a new CD diagnosis to help decrease relapse incidence.

CONCLUSION

IPF therapy can induce remission for most patients with CD regardless of age or new diagnosis or relapse status.

Food

Everything in food works together to create health or disease.

— T Colin Campbell, MD, b 1934, American biochemist, author of The China Study

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marcin J Schroeder, PhD, Professor of Mathematics at Akita International University, for the statistical review.

Brenda Moss Feinberg, ELS, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increased incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012 Jan;142(1):46–54.e42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008 Oct 23;359(17):1757–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bijlsma JW, Welsing PM, Woodworth TG, et al. Early rheumatoid arthritis treated with tocilizumab, methotrexate, or their combination (U-Act-Early): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, strategy trial. Lancet. 2016 Jul 23;388(10042):343–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30363-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. FREEDOM Trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 20;361(8):756–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809493. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0809493. Erratum in: N Engl J Med2009 Nov 5;361(19):1914. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmx090058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, et al. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s disease cA2 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997 Oct 9;337(15):1029–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371502. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199710093371502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer L, Han C, Bala M, Keenan G, Olson A, Hanauer SB. Three dose induction regimen of infliximab (Remicade) is superior to a single dose in patients with Crohns disease (CD) Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Sep;96(9 Suppl 1):S303. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9270(01)03740-6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyams J, Crandall W, Kugathasan S, et al. REACH Study Group. Induction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2007 Mar;132(3):863–73. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.003. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, et al. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: An open randomized trial. Lancet. 2008 Feb 23;371(9613):660–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60304-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: The CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006 Feb;130(2):323–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.030. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, et al. Adalimumab induction therapy for Crohn disease previously treated with infliximab: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Jun 19;146(12):829–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00159. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB. Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease: A user’s guide for clinicians. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002 Dec;97(12):2962–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07093.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9270(02)05510-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. Gut. 2012 Nov;61(11):1619–35. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302830. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH IBSEN Group. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: Results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007 Aug;133(2):412–22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lees CW, Barrett JC, Parkes M, Satsangi J. New IBD genetics: Common pathways with other diseases. Gut. 2011 Dec;60(12):1739–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.199679. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2009.199679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernstein CN, Shanahan F. Disorders of a modern lifestyle: Reconciling the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2008 Sep;57(9):1185–91. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.122143. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2007.122143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hold GL. Western lifestyle: A ‘master’ manipulator of the intestinal microbiota? Gut. 2014 Jan;63(1):5–6. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304969. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. IBD Section of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011 May;60(5):571–607. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224154. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.224154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiba M, Tsuda H, Abe T, Sugawara T, Morikawa Y. Missing environmental factor in inflammatory bowel disease: Diet-associated gut microflora. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Aug;17(8):E82–3. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21745. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Aug 17;107(33):14691–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011 Oct 7;334(6052):105–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institutes of Health (US) National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Arteriosclerosis, 1981: Report of the Working Group on Arteriosclerosis of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Vol. 2. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hou JK, Abraham B, El-Serag H. Dietary intake and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr;106(4):563–73. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.44. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ge J, Han TJ, Liu J, et al. Meat intake and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: A meta-analysis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2015 Nov;26(6):492–7. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2015.0106. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5152/tjg.2015.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morita N, Minoda T, Munekiyo M, et al. Case-control study of ulcerative colitis in Japan [Abstract in English] In: Ohno Y, editor. Annual report of Research Committee on Epidemiology of Intractable Diseases, the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan. Nagoya, Japan: The Department of Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, Nagoya University; 1996. pp. 153–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita N, Ohnaka O, Ando S, et al. Case-control study of Crohn’s disease in Japan [Abstract in English] In: Ohno Y, editor. Annual report of Research Committee on Epidemiology of Intractable Diseases, the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan. Nagoya, Japan: The Department of Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, Nagoya University; 1997. pp. 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakamoto N, Kono S, Wakai K, et al. Epidemiology Group of the Research Committee on Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Japan. Dietary risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease: A multicenter case-control study in Japan. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005 Feb;11(2):154–63. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200502000-00009. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00054725-200502000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amre DK, D’Souza S, Morgan K, et al. Imbalances in dietary consumption of fatty acids, vegetables, and fruits are associated with risk for Crohn’s disease in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Sep;102(9):2016–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01411.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01411.x. Erratum in: Am J Gastroenterol 2007 Nov;102(11):2614. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiba M, Abe T, Tsuda H, et al. Lifestyle-related disease in Crohn’s disease: Relapse prevention by a semi-vegetarian diet. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 May 28;16(20):2484–95. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i20.2484. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i20.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiba M, Tsuda S, Komatsu M, Tozawa H, Takayama Y. Onset of ulcerative colitis during low-carbohydrate weight-loss diet and its treatment with plant-based diet: A case report. Perm J. 2016 Winter;20(1):80–4. doi: 10.7812/TPP/15-038. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/15-038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiba M, Tsuji T, Takahashi K, Komatsu M, Sugawara T, Ono I. Onset of ulcerative colitis after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: A case report. Perm J. 2016 Spring;20(2):e115–8. doi: 10.7812/TPP/15-085. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/15-085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th ed. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Internet] [cited 2017 Jul13]. Available from: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/ [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Cancer Research Fund; American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: A global perspective [Internet] Washington, DC: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007. [cited 2017 Jul 13]. Available from: www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Second-Expert-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuso PJ, Ismail MH, Ha BP, Bartlotto C. Nutritional update for physicians: Plant-based diets. Perm J. 2013 Spring;17(2):61–6. doi: 10.7812/TPP/12-085. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/12-085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orlich MJ, Singh PN, Sabaté J, et al. Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Jul 8;173(13):1230–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6473. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Dell JR. Treating rheumatoid arthritis early: A window of opportunity? Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Feb;46(2):283–5. doi: 10.1002/art.10092. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/art.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiely PD, Brown AK, Edwards CJ, et al. Contemporary treatment principles for early rheumatoid arthritis: A consensus statement. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009 Jul;48(7):765–72. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep073. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kep073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smolen JS, Emery P, Fleischmann R, et al. Adjustment of therapy in rheumatoid arthritis on the basis of achievement of stable low disease activity with adalimumab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone: The randomised controlled OPTIMA trial. Lancet. 2014 Jan 25;383(9914):321–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61751-1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61751-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heimans L, Akdemir G, Boer KV, et al. Two-year results of disease activity score (DAS)-remission-steered treatment strategies aiming at drug-free remission in early arthritis patients (the IMPROVED-study) Arthritis Res Ther. 2016 Jan 21;18:23. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0912-y. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0912-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Disease activity courses in a regional cohort of Crohn’s disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995 Jul;30(7):699–706. doi: 10.3109/00365529509096316. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/00365529509096316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loftus EV, Jr, Schoenfeld P, Sandborn WJ. The epidemiology and natural history of Crohn’s disease in population-based patient cohorts from North America: A systematic review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002 Jan;16(1):51–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01140.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2006 Mar;130(3):650–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanauer SB, Sandborn W Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Mar;96(3):635–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.3671_c.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9270(01)02234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Have M, Oldenburg B, Fidder HH, Belderbos TD, Siersema PD, van Oijen MG. Optimizing screening for tuberculosis and hepatitis B prior to starting tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2014 Mar;59(3):554–63. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2820-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-013-2820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006 Jun;55(6):749–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.D’haens G, Van Deventer S, Van Hogezand R, et al. Endoscopic and histological healing with infliximab anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies in Crohn’s disease: A European multicenter trial. Gastroenterology. 1999 May;116(5):1029–34. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70005-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toy LS, Scherl EJ, Kornbluth A, et al. Complete bowel obstruction following initial response to infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease: A series of newly described complication. Gastroenterology. 2000 Apr;118(4 Pt 1):A569. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5085(00)84412-1. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vasilopoulos S, Kugathasan S, Saeian K, et al. Intestinal strictures complicating initially successful infliximab treatment for luminal Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Sep;95(9):2503. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02675.x. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao T, Matsui T, Hiwatashi N. Crohn’s disease in Japan: Diagnostic criteria and epidemiology. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 Oct;43(10 Suppl):S85–93. doi: 10.1007/BF02237231. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02237231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahuja V, Tandon RK. Inflammatory bowel disease in the Asia-Pacific area: A comparison with developed countries and regional differences. J Dig Dis. 2010 Jun;11(3):134–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00429.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 15;362(15):1383–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watanabe M, Hibi T, Lomax KG, et al. Study Investigators. Adalimumab for the induction and maintenance of clinical remission in Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2012 Mar;6(2):160–73. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.07.013. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyoshi J, Hisamatsu T, Matsuoka K, et al. Early intervention with adalimumab may contribute to favorable clinical efficacy in patients with Crohn’s disease. Digestion. 2014;90(2):130–6. doi: 10.1159/000365783. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1159/000365783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sandborn WJ, Löfberg R, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Campieri M, Greenberg GR. Budesonide for maintenance of remission in patients with Crohn’s disease in medically induced remission: A predetermined pooled analysis of four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Aug;100(8):1780–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41992.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schreiber S, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, et al. Subgroup analysis of the placebo-controlled CHARM trial: Increased remission rates through 3 years for adalimumab-treated patients with early Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Apr;7(3):213–21. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.05.015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parsi MA, Achkar JP, Richardson S, et al. Predictors of response to infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2002 Sep;123(3):707–13. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35390. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2002.35390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leal RF, Planell N, Kajekar R, et al. Identification of inflammatory mediators in patients with Crohn’s disease unresponsive to anti-TNFα therapy. Gut. 2015 Feb 1;64(2):233–42. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306518. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Billiet T, Paramichael K, de Bruyn M, et al. A matrix-base model predicts primary response to infliximab in Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2015 Dec;9(12):1120–6. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv156. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Biancheri P, Brezski RJ, Di Sabatino A, et al. Proteolytic cleavage and loss of function of biologic agents that neutralize tumor necrosis factor in the mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov;149(6):1564–74. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.002. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chiba M, Nakane K, Takayama Y, et al. Development and application of a plant-based diet scoring system for Japanese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Perm J. 2016 Fall;20(4):62–8. doi: 10.7812/TPP/16-019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/16-019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cosnes J, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, Gendre JP. Smoking cessation and the course of Crohn’s disease: An intervention study. Gastroenterology. 2001 Apr;120(5):1093–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23231. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2001.23231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nunes T, Etchevers MJ, García-Sánchez V, et al. Impact of smoking cessation on the clinical course of Crohn’s disease under current therapeutic algorithms: A multicenter prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Mar;111(3):411–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.401. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2015.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Okada M, Yao T, Yamamoto T, et al. Controlled trial comparing an elemental diet with prednisolone in the treatment of active Crohn’s disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1990 Feb;37(1):72–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brandt LJ, Bernstein LH, Boley SJ, Frank MS. Metronidazole therapy for perineal Crohn’s disease: A follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1982 Aug;83(2):383–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prantera C, Zannoni F, Scribano ML, et al. An antibiotic regimen for the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: A randomized, controlled clinical trial of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996 Feb;91(2):328–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sartor RB. Therapeutic manipulation of the enteric microflora in inflammatory bowel diseases: Antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics. Gastroenterology. 2004 May;126(6):1620–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.024. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sorrentino D. Role of biologics and other therapies in stricturing Crohn’s disease: What have we learnt so far? Digestion. 2008;77(1):38–47. doi: 10.1159/000117306. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1159/000117306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miehsler W, Novacek G, Wenzl H, et al. Austrian Society of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. A decade of infliximab: The Austrian evidence based consensus on the safe use of infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn Colitis. 2010 Sep;4(3):221–56. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.12.001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pelletier AL, Kalisazan B, Wienckiewicz J, Bouarioua N, Soulé JC. Infliximab treatment for symptomatic Crohn’s disease strictures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Feb 1;29(3):279–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03887.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chiba M, Sugawara T, Tsuda H, Abe T, Tokairin T, Kashima Y. Esophageal ulcer of Crohn’s disease: Disappearance in 1 week with infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009 Aug;15(8):1121–2. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20769. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.20769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boirivant M, Leoni M, Tariciotti D, Fais S, Squarcia O, Pallone F. The clinical significance of serum C reactive protein levels in Crohn’s disease. Results of a prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988 Aug;10(4):401–5. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198808000-00011. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00004836-198808000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]