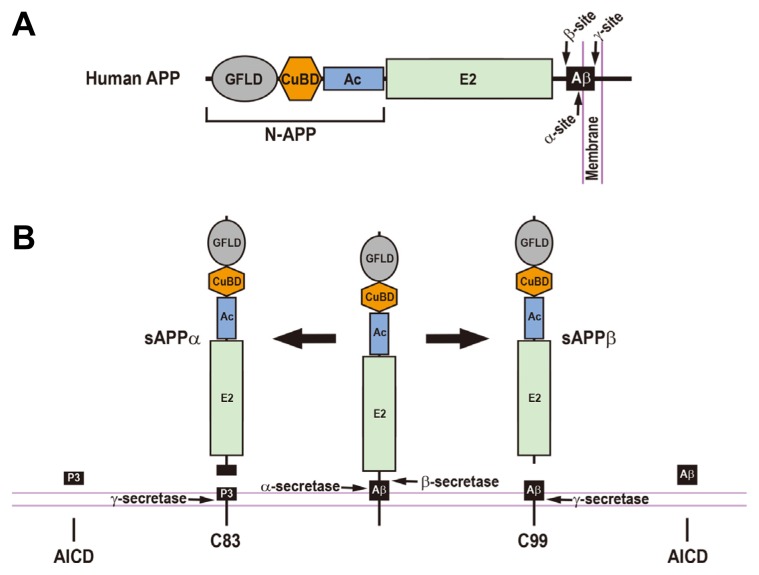

Fig. 1.

The Regulated Proteolytic Processing of Human β-Amyloid Precursor Protein and the Resulting Cleavage Fragments.

(A) Schematic diagram of human β-amyloid precursor protein (APP). The arrows represent the cleavage sites by α-, β-, and γ-secretases. GFLD, growth factor-like domain; CuBD, copper-binding domain; Ac, acidic domain; E2, APP extracellular carbohydrate domain; Aβ, amyloid β-peptide; N-APP, a cleaved N-terminal fragment of APP. (B) Human APP can be processed through either amyloidogenic or non-amyloidogenic pathways. In the amyloidogenic pathway (right), the proteolytic cleavage of the APP by β-secretase produces a large soluble ectodomain of APP (sAPPβ) and a membrane-associated C-terminal fragment (C99). The C99 is subsequently cleaved by γ-secretase, releasing an amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) and an APP intracellular domain (AICD). In a non-amyloidogenic pathway (left), α-secretase-mediated cleavage of the APP generates a soluble ectodomain of APP (sAPPα) and a membrane-tethered C-terminal fragment (C83). The subsequent cleavage of the C83 by γ-secretase gives rise to a P3 peptide and an AICD.