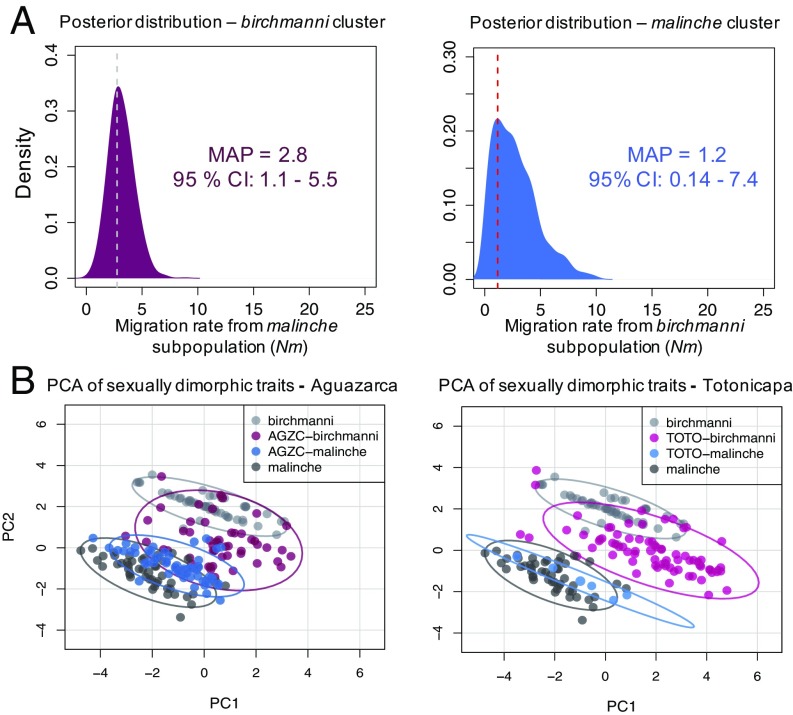

Fig. 2.

ABC simulations support near-complete reproductive isolation between the two hybrid clusters at Aguazarca, despite phenotypic and genetic similarity to another population lacking reproductive isolation. (A) Results of ABC simulations focusing on the Aguazarca population demonstrate that gene flow (Nm) between subpopulations in Aguazarca has been low over the past 25 generations (Nm from the malinche cluster, ∼2.8; Nm from the birchmanni cluster, ∼1.2). (B) Despite low levels of cross-cluster gene flow in Aguazarca, males of the birchmanni-like cluster are similar phenotypically in Aguazarca and Totonicapa, as are males in the malinche-like cluster. Shown are results of principal component analysis of male hybrids in these populations and individuals of the pure parental species. Discriminant function analysis identifies sword length and dorsal fin length as the phenotypic traits most differentiated between the two subpopulations in Aguazarca (SI Appendix, 1 and 2). However, these traits do not differ in their distribution between birchmanni cluster hybrids in Aguazarca and Totonicapa (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). This suggests that preference differences, environmental differences, or differences in traits not captured by our phenotyping underlie differences in assortative mating between populations.