Abstract

Background

Working in multidisciplinary teams is indispensable for ensuring high-quality care for elderly people in Japan’s rapidly aging society. However, health professionals often experience difficulty collaborating in practice because of their different educational backgrounds, ideas, and the roles of each profession. In this qualitative descriptive study, we reveal how to build interdisciplinary collaboration in multidisciplinary teams.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a total of 26 medical professionals, including physicians, nurses, public health nurses, medical social workers, and clerical personnel. Each participant worked as a team member of community-based integrated care. The central topic of the interviews was what the participants needed to establish collaboration during the care of elderly residents. Each interview lasted for about 60 minutes. All the interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and subjected to content analysis.

Results

The analysis yielded the following three categories concerning the necessary elements of building collaboration: 1) two types of meeting configuration; 2) building good communication; and 3) effective leadership. The two meetings described in the first category – “community care meetings” and “individual care meetings” – were aimed at bringing together the disciplines and discussing individual cases, respectively. Building good communication referred to the activities that help professionals understand each other’s ideas and roles within community-based integrated care. Effective leadership referred to the presence of two distinctive human resources that could coordinate disciplines and move the team forward to achieve goals.

Conclusion

Taken together, our results indicate that these three factors are important for establishing collaborative medical teams according to health professionals. Regular meetings and good communication facilitated by effective leadership can promote collaborative practice and mutual understanding between various professions.

Keywords: interprofessional education, multidisciplinary collaboration, integrated primary and community care, qualitative research, interdisciplinary communication, geriatric health services, Japan

Background

Developed countries have seen an increase in the number of elderly individuals living in the community who suffer from multiple chronic diseases.1 Thus, providing efficient treatment and care for these elderly individuals has become a challenge. Since the 1990s, the World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed integrated care – that is, the introduction, provision, management, and organization of various health-related services such as diagnosis, treatment, care, rehabilitation, and health promotion – as a better method of medical treatment and care in the future.2,3 Recently, a study verified the outcomes of integrated care, finding that it was valid for improving client outcomes and client satisfaction, as well as reducing the cost of care.4–6 The Japanese version of integrated care is called “community- based integrated care.”7 With the goals of maintaining patients’ dignity and supporting their independent living, community-based integrated care involves the creation of systems of comprehensive community support and services that allow individuals to continue their own way of life as much as possible until the end of life, in the community in which they used to live.

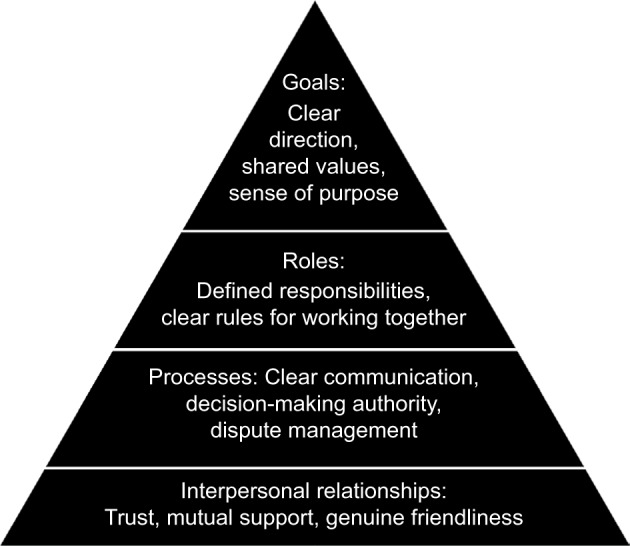

To provide comprehensive support and integrated services, it is necessary for medical, administrative, and human services departments, and the professionals affiliated to these departments, to cooperate.3,8 However, the unified intentions and rapid decision-making characteristics of good cooperation, whether interdisciplinary or interdepartmental, can be difficult to attain, given their different professional cultures and individuals’ lack of interprofessional knowledge.9–11 In order to overcome these challenges, the WHO and other medical professional societies have begun providing learning objectives and competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice, particularly with regard to effective communication strategies and shared decision making.8,12,13 Nevertheless, the question remains as to how to encourage professionals to communicate effectively and achieve consensus in a manner particular to their regional context.12 Two theoretical models in this regard have been created from the perspectives of team building and interpersonal relationships.14,15 Beckhard introduced four goals that must be clear among team members to ensure effective team building (Figure 1).14 The four goals are Goal (finding an objective), Roles (distribution and integration of roles and responsibilities), Processes (processes/procedures of the job, decision-making method), and Interpersonal relationships (interaction and relationships between members). These goals must be tackled as a team in the order presented, which in turn aids in team building. Gibb similarly pointed out four basic concerns present in individuals’ relationships with others (Table 1).15 The four concerns are acceptance (ie, anxiety about the acceptance of oneself and others), data flow (anxiety about the expression of one’s own thoughts and feelings), goal formation (concern about a common goal), and social control (concern about the division of roles and mutual dependence). By eliminating these concerns in order, mutual dependence between team members increases and the team develops as a whole.

Figure 1.

Beckhard’s team-building model stipulating the goals of team building: goals, roles, processes, and relationships.

Table 1.

Gibb’s four basic concerns present in one’s relationship with others

| Concern | Signs that concerns are not resolved | Signs that concerns are resolved | Signs of individual growth | Signs of group growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concern about acceptance: The anxiety and fear of “Am I being accepted into this group?” The feeling of distrust of “Am I accepting others?” | Fear and distrust | Acceptance and trust | Acceptance of self and others | A supportive climate, a trusting climate |

| Concern about data flow: The concern that “I cannot speak freely about my ideas, thoughts, and feelings.” | Polite pretense and cautious measures | Spontaneity and process feedback | Spontaneity and awareness | Practical communication and functional feedback |

| Concern about goal formation: When goals have not been shared within the group; even if there is a common goal, it is something given by others; there is a gap between the individual goal and the group goal. A situation in which members are not independently tackling goals |

Indifference and competition | Creative activity | Integrity and directionality | Goal integration and high degree of flexibility |

| Concern about social control: Occurs when you cannot have the effect you feel you would like to, or when you feel that you don’t have an effect on the group. As a result, strong control from others leads to abandoning the idea of having an effect on others (dependence) or opposition and rebellion (anti-dependence) | Dependence and anti-dependence | Interdependence and division of roles | Interdependence | Interdependence and construction of participatory behavior |

Notes: Data from Bradford et al.15

Despite these theories, it is still somewhat unclear how to achieve the above-stated goals and alleviate the relevant concerns in practice. Accordingly, the goal of this study was to clarify whether the process of developing interprofessional cooperation by studying what those involved in the medical profession – including practitioners, administration, and human services personnel – feel is necessary to effectively build interdisciplinary cooperation when providing community- based integrated care.

Methods

This is a qualitative research study. Through one-to-one semi-structured interviews and direct observations, we obtained the participants’ in-depth thoughts and experiences about interprofessional cooperation and community-based integrated care in order to reveal the process of developing interprofessional cooperation.16,17

Participants

We purposively chose four teams comprising a total of 26 participants from 7 professions: 4 doctors, 4 nurses, 4 public health nurses, a pharmacist, 6 care managers, 2 social workers, and 5 administrative staff. We used stratified sampling to include at least one member of every profession in each team. All of the invited participants agreed to an interview. Each team was located in a different district of northern Japan. We had two reasons for selecting these districts. First, the municipalities and regional medical facilities in which these teams were based were passionate about community-based integrated care. Second, each facility practicing community-based integrated care in these districts was consistent with each local government (ie, there was one community comprehensive support center for each local government area). All of the teams had practiced together for 10 years on average (range, 5–14 years) and had regular meetings. The mean age of the participants was 48 years, and the male-to-female ratio was 11 to 15. Table 2 shows the distributions of the participants and characteristics of the four districts. We obtained written informed consent from the participants after providing them with a verbal and written explanation of the study outline. The present study was conducted only after receiving approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine.

Table 2.

Distributions of participants and characteristics of four districts

| District A | District B | District C | District D | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of participants | 6 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 26 |

| Classification of professions | |||||

| Medical personnel: doctors, nurses and a pharmacist | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| Administrative and health officials: public health nurses and administrative staff | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| Welfare and nursing care officials: care managers and social workers | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Remarks: residential population size and amount of medical resources | 7,500; a 40-bed municipal hospital with three private practice offices | 3,500; a town clinic with beds and a long-term care facility | 3,500; a town clinic with beds and a private practice office | 3,000; a municipal clinic with beds |

Data collection

Over a 7-month period in 2014, the first author (TA) visited the selected districts and conducted individual interviews, with each interview lasting 30–60 minutes in a private room (to ensure confidentiality). An interview guide was developed based on literature on teamwork (ie, the essential elements of establishing a team), interprofessional cooperation (ie, the importance of relationships regarding quality care), and change implementation (ie, how to change practice).8–13 The developed interview guide comprised three topics relating to collaborative practice in community-based integrated care: 1) the challenges of interprofessional cooperation; 2) the essential elements of establishing a team; and 3) the ways of achieving collaborative practice. We carried out interviews until no new categories emerged from the data (ie, data saturation). All the interviews were recorded with a digital voice recorder and transcribed verbatim. The first author also observed regular meetings of the four teams.

Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using a conventional content analysis.16,18 The transcribed verbal data were segmented, and all of the passages applicable to the research question were extracted. These extracted passages were divided into meaning units (ie, words, sentences, or paragraphs containing certain aspects related to the topic of interest). We then began the process of coding the abstract concepts that emerged from those meaning units. This coding was conducted by two researchers (TA and HK). The codes were then classified into subcategories according to their similarities in concepts and meaning. We used an “ascending order,” moving from codes to subcategories to categories, for data reduction for all analysis units to ensure that categories emerged at the end. To confirm the validity of the analysis, two other collaborating researchers (KK and TT) reviewed subcategories and categories with reference to the original transcripts. The results obtained from these two latter results were in turn examined by two different collaborating researchers (MM and JO). After the analysis, the interview transcripts were returned to the participants to ensure the accuracy of the subcategories and categories as well as the relevant interpretations. The trustworthiness of the analysis was determined through peer debriefing, member checking, and reviewing the previous literature on interdisciplinary cooperation to determine its similarities to interpretation.

Results

Our results extracted three categories as elements necessary for building interdisciplinary cooperation in community-based integrated care: 1) two types of meeting configuration; 2) building good communication; and 3) effective leadership. Each category comprised various subcategories, which are explained in the various subheadings throughout this section. We also provide relevant quotations of the participants. Table 3 demonstrates the extracted three categories and their subcategories.

Table 3.

Categories and subcategories from content analysis about establishing community-based integrated care for elderly patients through interprofessional teamwork

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Two types of meeting configuration | |

| Community care meetings form the core of community-based integrated care Sharing the goal and significance of community care meetings Individual care meetings are indispensable for mutual understanding between disciplines |

|

| Building good communication | |

| Close interaction promoting mutual understanding between disciplines Building good relationships with doctors and medical institutions Building good relationships with administrative agencies |

|

| Effective leadership | |

| The need for a coordinator who manages interdisciplinary cooperation The need for leaders to promote a mutual understanding between disciplines Hope for doctors to take on the role of the leader |

Two types of meeting configuration

Participants suggested that it was necessary to have two types of meetings with differing roles: namely a “community care meeting,” which involved bringing together the disciplines, and a case-by-case, site-level “individual care meeting.” The former offered an opportunity to share the principles of comprehensive community care and care management and supported community networks by arranging discussions of practice. These efforts helped in identifying any problems and outlined residents’ care management. The latter offered an opportunity to deepen mutual understanding between disciplines through the study of individual cases.

Community care meetings form the core of community-based integrated care

Community care meetings were considered the first step toward beginning community-based integrated care. First, the participants found it essential that community care meetings continue to be held regularly. Next, it is necessary not only to think about actually holding these meetings, but also to create opportunities to share principles related to community-based integrated care and care management. In other words, by holding numerous community care meetings, they may evolve from being mere forums for multiple disciplines to consider challenges in the community into forums for planning and implementing collaborative practice.

Communities that previously had not been holding care meetings are now holding them monthly. Related institutions [medical treatment, health services, etc.] within the town are also beginning to participate in the meetings. Everyone would like to discuss things that we cannot manage on our own in the town. [General Administrative Occupation]

It took from about six months to a year to find a place for the meeting. While at first it was only to discuss difficult cases, after this, it became a meeting to discuss things like a vision for the future of the town. [Doctor]

Sharing the goal and significance of community care meetings

The participants reported that when holding a community care meeting, it is essential to maintain a clear goal and significance for that meeting. Among the goals suggested were sharing the principles of comprehensive community care, monitoring and verification of the progress of collaborative practice, clarification of the division of roles for each discipline, and interdisciplinary unification of responses to cases.

There are various reasons based on the community that cooperation is necessary. A forum for discussion to verify the progress of that cooperation is necessary. The division of roles overlaps considerably [right now]. You’ve got to discuss [these issues] properly. [Care Manage]

Public health nurses and care managers have numerous cases. When we experience a lot of those, we notice certain patterns in the challenges that we face. By just responding to each individual, it unfortunately becomes like emergency treatment. A place to respond as a system, a formal place, so to speak, is necessary. [Doctor]

Individual care meetings are indispensable for mutual understanding between disciplines

As community-based integrated care becomes more widespread, interdisciplinary cooperation becomes easier, albeit superficially. Nonetheless, there appears to be an interdisciplinary gap in professionals’ ways of thinking, particularly in terms of the definitions and directions of community-based integrated care, as well as the breadth of their involvement with patients and residents to provide community-based integrated care. Notably, the scale of the community care meetings in the promotion of mutual understanding between disciplines and filling these gaps in thinking is large. Accordingly, participants suggested a need for promoting a deeper respect for the differences in ways of thinking between disciplines and building better one-on-one relationships between members of those disciplines through the improvement of individual care meetings.

In order to understand the differences between each other’s disciplines, we must deepen the relationships between hospitals and public health centers, etc. and individuals. As a whole, it’s too large. First [it] is [necessary] to devise a way to hold meetings that allow us to understand each other’s positions. [Care Manager]

Having more individual care meetings by working-level individuals [on-site responsible professionals] in medical and health services would be good. I think that cooperation will begin through understanding the differences in ways of thinking between disciplines, and that those differences are not bad. [Public Health Nurse]

I would like to try consistently holding preventative medicine meetings with public health nurses and doctors. Public health nurses are also trying their best to hold them, but if I hear things like “do you really think this is necessary?” they always respond with “well, it’s national policy.” I think community healthcare is walking with your own feet, confirming with your own eyes, and, if there’s a problem, finding where the most effective place is to get involved in order to improve the health of community residents. I don’t think it’s the job of a public health nurse to do exactly as they are told by the country and health centers, but since I haven’t run into that problem, I would like to hear an answer from someone who has. [Doctor]

Building good communication

Building good communication referred to the various activities that helped professionals understand each other, particularly their ideas and roles in community-based integrated care. Each discipline has vastly different ideas and opinions on community-based integrated care and care management. Furthermore, professionals’ positions (ie, managerial or nonmanagerial post) and working conditions (ie, full-time or temporary) affect their commitments to their jobs. Therefore, achieving understanding between disciplines through their interactions during day-to-day operations and care meetings is difficult. A necessary element for achieving such understanding is “building good communication.”

Close interaction promoting mutual understanding between disciplines

To promote mutual understanding between disciplines, the participants had a widespread belief that each discipline had to be aware not only of their interactions during community care meetings and day-to-day operations, but also of their close interactions outside of business-related activities. These include private exchanges after the work day, engaging together in observation and study groups, and planning lectures and community-wide events. Such close interaction was viewed as helpful in building good communication between disciplines and deepening mutual understanding.

A face-to-face relationship is essential. It’s because we have a face-to-face relationship that it is easy to hold support meetings. [Furthermore,] it is because we have a face-to-face relationship, because we have had conversations, because we have drunk together, that we can share our philosophies and objectives about the job. [Social Worker]

Show your face as much as possible. Don’t only ask the doctor for help if you have a problem, or for help with a difficult case – offer your cooperation to the doctor and respond quickly if they ask a favor of you. [Public Health Nurse]

Spare no effort in creating a shared vision; in other words, [you should] completely share [your] philosophies. Share [your] goals with everyone. Not only for day-to-day work, but in a completely different place, unrelated to work. In other words, continue to share your vision as a group not on the job, but off the job. [Doctor]

Building good relationships with doctors and medical institutions

Participants reported that it was common to find it difficult to cooperate with doctors and medical institutions. They opined that it would be easy to cooperate with these parties if there were humility and ease in the consultations with them. Additionally, all of the disciplines, particularly doctors, attempted to consciously ease the difficulty that other disciplines seemed to be feeling.

I have come to feel that doctors are very open. Previously, it was common to consult with a doctor after the individuals around the doctor had laid out the groundwork beforehand. Since the current hospital director arrived, that threshold has lowered and our opinions have come to be reflected in the treatment. [Care Manager]

I listen daily to the opinions of other disciplines, not just my own thoughts. Frankly, I go to them for advice as well. [Doctor]

Building good relationships with administrative agencies

Building good relationships with administration was noted to be difficult and required considerable care and ingenuity. The reasons for the difficulty included frequent changes in administrative posts, the administrative organization’s lack of flexibility for cases spanning all relevant topics (eg, health, medical care, and welfare), and the administration’s lack of understanding because they do not know the medical and nursing fields.

In my community, relationships with administrators are a problem. Of the professionals in public office, there are few human services positions, and they change often. So, no matter what kind of job or case, we always try to share information. When we’re beginning some project, we don’t start only with welfare and nursing care [my department]. So our relationship with administration does not become strained, we try to tackle issues together with administration as much as possible. [Care Manager]

What kinds of things are the mayor and public office staff asking of doctors? On the one hand, I have my own ideal image of medical care. When both parties’ thoughts are the same, cooperation with administration starts. The important part is to politely collaborate about what kind of medical care the administration intends to ensure and, as doctors, [draw on] our many years of experience and thinking [about medical care]. [Doctor]

Effective leadership

To install comprehensive community care and interdisciplinary cooperation in currently immature regions, it is necessary to have a “coordinator” whose duty is to coordinate between the disciplines and convene care meetings when necessary. However, deepening mutual understanding between disciplines requires someone who goes beyond mere reconciliation of the disciplines and convening care meetings – namely a “leader” who helps to promote the creation of good communication between disciplines.

The need for a coordinator who manages interdisciplinary cooperation

In day-to-day operations, disciplines often find it difficult to contact and coordinate with other disciplines; therefore, teams require a coordinating role; this is most often in the form of medical social workers (MSWs). In facilities that lack an MSW, another individual is often given the same responsibilities. The essential element of this occupation is that they are not simply a contact person, but that they are given a certain authority and discretion to help improve the quality of interdisciplinary cooperation.

My focus of cooperation is with nurses, and particularly connecting nurses with other disciplines. For example, even if doctors are tied up with other business, things progress. Things like nurturing autonomy and a sense of responsibility within nurses will lead to the fostering of identity. For those hesitant to consult with doctors as well, my central idea is that, if they understand that they are nurses, they can feel free to consult with us. [Doctor]

The need for leaders to promote a mutual understanding between disciplines

On the other hand, in discussing the mutual understanding between disciplines, participants frequently pointed out the need for a leadership role. In other words, they required someone who not only could convene care meetings, but also could promote close interaction between disciplines. Simultaneously, an effective leader should be able to consider the circumstances and ways of thinking of each discipline and have personnel coordination skills.

In interdisciplinary coordination, a leader who can work effectively is necessary. In our town, that would be the doctor at the clinic and the public health nurse at the government office. But, if those people disappeared and you asked me if the cooperation we’ve had until now would function, I would say that it would be difficult. [Nurse]

The director of the hospital places considerable importance on the relationship with everyone in the community. We have the leader, namely our hospital director, and then we have his supporters – the hospital staff, residents, and administrators. These days, we’ve established a circle [of supporters]. Everyone is probably thinking “if only someone takes the lead for us, then we can get onboard.” [Nurse]

Hope for doctors to take on the role of the leader

Many of the participants hoped that the doctors would serve as leaders in community-based integrated care. In particular, doctors – especially family physicians and family medicine practitioners – must bear in mind not only the illness, but also the patient’s lifestyle. They were thought to be in a good position to capture the region’s status from a public health perspective. Doctors, particularly those working at the front lines of community care, are working day to day with an awareness of this expectation from other disciplines.

It is important that the leader be a family physician. Their point of view is not limited to that of a doctor. Even for cases that cross multiple areas of prevention, care, etc., as a leader, rather than forcibly pulling, they can act as a hub to continue smooth cooperation. I wonder if that’s a characteristic of family physicians. [Pharmacist]

It’s not at all that the leader must be a doctor. But, to some degree, it’s best if doctors are given leadership. In talking about strategy for interdisciplinary cooperation, it’s necessary to have someone who can present a solution, even when cooperation is deadlocked. I think that those elements are a part of family medicine. The part that goes beyond the clinic. [Doctor]

Discussion

We conducted on-site interviews with multiple disciplines to determine the elements of interdisciplinary cooperation in community-based integrated care. Three elements were extracted – “two types of meetings (ie, community and individual care meetings),” “building good communication,” and “effective leadership.” These results can be conceptualized as the team-building process.

When comparing our results with Beckhard’s model on team building, we find that “community care meeting” corresponds to the goal and roles, “individual care meetings” to procedures/processes, and “building good communication” to interaction/relationships.14 Thus, community-based integrated care seems to begin from holding community care meetings, wherein the principles and goals of community-based integrated care are shared between disciplines, and the division of roles among team members is clarified. Additionally, at individual care meetings, through polite discussion about the multidisciplinary team’s responses to an individual case, team members seek a consensus on the problems that patients are facing and their potential solutions. Building good communication is essential for this base of consensus and sharing principles. Finally, the promotion of interdisciplinary cooperation in community-based integrated care can be equated to the team-building process in Beckhard’s model.

Furthermore, when considering Gibb’s group development theory, through on-the-job meetings (ie, individual care meetings) and off-the-job meetings, team members can express their thoughts and feelings freely, thereby nurturing mutual acceptance and trust, which in turn can aid in building good communication and relationships between disciplines. In this way, the acceptance and data flow concerns of Gibb’s theory correspond to the categories of “building good communication” and “individual care meetings,” respectively.15 In contrast, “community care meetings” would be related to the resolution of the concern regarding goal formation. When the concern about goal formation is resolved, goals become one’s own creation, and members thereafter begin to tackle the goals independently. When applying this to community care meetings, we might note that these meetings were at first only multidisciplinary gatherings aimed at discussing difficult cases, which subsequently morphed into a space where individuals can discuss a vision and a future for their community. When community care meetings matured to the point that long-term goals such as these can be shared between disciplines, we might say that the concern about goal formation has been resolved. Furthermore, when the final step of team development, concern about social control, is resolved, members sporadically participate in the group and fellow members develop relationships of mutual dependence according to their positions and situations. In community-based integrated care, each discipline has its own long-term goal, but all of them share a mission that should be fulfilled. When they have reached the stage at which they can precisely demonstrate their expertise, they can be thought to have realized “mutually interdependent” interdisciplinary cooperation.

Taken together, our results suggest that building interdisciplinary cooperation can be regarded as a process that contains both Beckhard’s model and Gibb’s theory.14,15 To begin, community care meetings are held, wherein urgent goals and roles are set. These goals, however, do not necessarily coincide with those held by each member, namely community care meetings are considered to be in a state of “forming”.19,20 Before long, there arises a need to deepen their mutual understanding through “building good communication” and “individual care meetings.” When these have been achieved, the ideal image of comprehensive care for a given community can be shared at community care meetings. Finally, when the ideals of community-based integrated care have been sufficiently shared, interdisciplinary cooperation reaches a mature stage.

Nonetheless, simply entrusting this operation only to individual members is insufficient.9,21,22 Accordingly, the third category, “effective leadership,” is necessary. This third category is particularly indispensable when considering its ability to coordinate between multiple disciplines and the difficulty in ensuring communication between the different organizational departments (eg, administration and health care) and cooperation with exceedingly busy professionals such as doctors. Effective team leaders facilitate, coach, and coordinate the activities of other team members using the following 10 actions: 1) accepting the leadership role; 2) asking for help as appropriate; 3) constantly monitoring the situation; 4) setting priorities and making decisions; 5) resolving team conflicts; 6) balancing the workload within the team; 7) delegating tasks or assignments; 8) empowering team members to speak freely and ask questions; 9) inspiring other team members; and 10) maintaining a positive group culture. The results obtained in this study covered these items while adding the characteristics of coordinator and promoter.23 Additionally, researchers have noted the necessity of good coordinating skills and precise leadership in integrated care.13,24,25 In summary, according to our results, team members believe that, to be effective, a leader must be able to coordinate between the two types of meetings appropriately and offer a forum to build good communication between disciplines.

Limitations

This study has a few limitations. Because the sample size and geographic distribution were limited, we must be cautious in generalizing the conclusions. Furthermore, the current study’s participants belonged to medical teams looking after elderly individuals with chronic diseases; thus, the collaborative practice that we examined did not involve urban areas, young individuals, or acute diseases. We adopted a qualitative research for an in-depth understanding of the pertinent inter-professional teams rather than the study’s generalizability. Additionally, we did not obtain information on how the leader was designated in comprehensive community care. In the future, it would be necessary to investigate the perceptions of patients and their families, as they are primary stakeholders.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to explore multidisciplinary professionals’ perspective of establishing collaboration in community-based integrated care. Through content analysis of individual interviews, we identified three elements of establishing collaboration: periodic multidisciplinary meetings to set roles and goals, mutual understanding to achieve good communication, and effective leadership to promote collaborative practice.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants for their contributions and Editage for checking linguistic content. A part of this research was supported by KAKENHI (2546060703), A Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Author contributions

TA, HK, and MM reviewed previous studies and designed the study. TA conducted the interviews, the observations, and data transcription. TA and HK analyzed the data initially and drafted the manuscript. KK and TT participated in the data analysis by reviewing subcategories and categories against original transcripts. MM and JO checked the validity of the data. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(4):430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grone O, Garcia-Barbero M, WHO European Office for Integrated Health Care Services Integrated care: a position paper of the WHO European Office for Integrated Health Care Services. Int J Integr Care. 2001;1:e21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Interprofessional Collaborative Practice in Primary Health Care: Nursing and Midwifery Perspectives. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Béland F, Hollander MJ. Integrated models of care delivery for the frail elderly: international perspectives. Gac Sanit. 2011;25(Suppl 2):138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kodner DL. Whole-system approaches to health and social care partnerships for the frail elderly: an exploration of North American models and lessons. Health Soc Care Community. 2006;14:384–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park G, Miller D, Tien G, Sheppard I, Bernard M. Supporting frail seniors through a family physician and Home Health integrated care model in Fraser Health. Int J Integr Care. 2014;14:e001. doi: 10.5334/ijic.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morikawa M. Towards community-based integrated care: trends and issues in Japan’s long-term care policy. Int J Integr Care. 2014;14:e005. doi: 10.5334/ijic.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel . Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall P. Interprofessional teamwork: professional cultures as barriers. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):188–196. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xyrichis A, Lowton K. What fosters or prevents interprofessional teamworking in primary and community care? A literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(1):140–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baillie L, Gallini A, Corser R, Elworthy G, Scotcher A, Barrand A. Care transitions for frail, older people from acute hospital wards within an integrated healthcare system in England: a qualitative case study. Int J Integr Care. 2014;14:e009. doi: 10.5334/ijic.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Schaik SM, O’Brien BC, Almeida SA, Adler SR. Perceptions of interprofessional teamwork in low-acuity settings: a qualitative analysis. Med Educ. 2014;48:583–592. doi: 10.1111/medu.12424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beckhard R. Optimizing team-building efforts. J Contemp Bus. 1972;1:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradford LP, Gibb JR, Benne KD. T-group Theory and Laboratory Method: Innovation in Re-education. 1st ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 3rd ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuckman BW. Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychol Bull. 1965;63:384–399. doi: 10.1037/h0022100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grills NJ, Kumar R, Philip M, Porter G. Networking between community health programs: a team-work approach to improving health service provision. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:297. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett PN, Gum L, Lindeman I, et al. Faculty perceptions of interprofessional education. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31(2):571–576. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mickan SM, Rodger SA. Effective health care teams: a model of six characteristics developed from shared perceptions. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(4):358–370. doi: 10.1080/13561820500165142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization . Patient Safety Curriculum Guide, Multi-Professional Edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker KK, Bosco C, Oandasan IF. Factors in implementing interprofessional education and collaborative practice initiatives: findings from key informant interviews. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):166–176. doi: 10.1080/13561820500082974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall MN, Mannion R, Nelson E, Davies HT. Managing change in the culture of general practice: qualitative case studies in primary care trusts. BMJ. 2003;327:599–602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7415.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]