Abstract

Although many researchers have explored the relations among gender identification, discriminatory attributions, and intentions to challenge discrimination, few have examined the causal impact of gender identity salience on women’s actual responses to a sexist encounter. In the current study, we addressed this question by experimentally manipulating the salience of gender identity and assessing its impact on women’s decision to confront a sexist comment in a simulated online interaction. Female participants (N = 114) were randomly assigned to complete a short measure of either personal or collective self-esteem, which was designed to increase the salience of personal versus gender identity. They were then given the opportunity to confront a male interaction partner who expressed sexist views. Compared to those who were primed to focus on their personal identity, participants who were primed to focus on their gender identity perceived the interaction partner’s remarks as more sexist and were more likely to engage in confrontation. By highlighting the powerful role of subtle contextual cues in shaping women’s perceptions of, and responses to, sexism, our findings have important implications for the understanding of gender identity salience as an antecedent of prejudice confrontation. Online slides for instructors who want to use this article for teaching are available on PWQ’s website at http://journals.sagepub.com/page/pwq/suppl/index.

Keywords: gender identity, interpersonal interaction, sexism, social identity

Despite egalitarian social norms in the contemporary United States, women are exposed to prejudiced attitudes and sexist treatment across a wide range of settings (Swim, Hyers, Cohen, & Ferguson, 2001). However, many women do not confront such sexist treatment in their environment (Kaiser & Miller, 2004; Swim & Hyers, 1999; Woodzicka & LaFrance, 2001). This reluctance to challenge discrimination has important psychological and social consequences. Confrontation has not only been linked to a sense of empowerment among women (Gervais, Hillard, & Vescio, 2010), but also can serve as an effective means for social change (Mallett & Wagner, 2011). To this end, researchers have worked to understand the various factors that affect how women and other stigmatized individuals weigh the potential costs and benefits of confronting prejudice (for reviews, see Ashburn-Nardo, Morris, & Goodwin, 2008; Kaiser & Major, 2006). In the present research, we focused on the role of one such factor, the salience of personal versus gender (group) identity, and examined its causal impact on women’s confrontation of a sexist comment in the context of a computer-mediated interaction.

According to social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), because people self-identify as individual persons, as well as members of their social groups, the salience of their personal versus social identity can vary significantly across contexts. As further explained in self-categorization theory (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987), personal identity refers to “me” versus “not me” categorizations; when it is activated, individuals tend to describe themselves using personal attributes and to engage in interpersonal comparisons. By contrast, social identity refers to “us” versus “them” categorizations; it is activated when situations emphasize a particular social identity (e.g., by priming a person to invoke his or her identity as a man or a woman) or indirectly by virtue of other elements of the situation (e.g., when one is the only woman in a social setting with several other men). According to both theoretical perspectives, when social identity is activated, individuals tend to view the world primarily through the lens of their group membership and compare their own groups to other groups by accentuating intragroup similarities, perceiving in-group members as sharing characteristics that represent the prototype of the group, and emphasizing intergroup differences. Making one’s social identity salient tends to arouse motivations to defend and enhance the status of one’s group (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), which in turn prompts collective action against incidents that threaten the esteem of their group.

In most of the existing work derived from social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and self-categorization theory (Turner et al., 1987), researchers have focused on ethnic and national identities (see Abrams & Hogg, 2010, for a review). Some investigators have examined the role of gender identity salience (i.e., the extent to which women think of themselves as a member of their gender group rather than an individual person) in relation to women’s task performance when they are a numerical gender minority (e.g., Abrams, Thomas, & Hogg, 1990); however, researchers have rarely considered the impact of gender identity salience on women’s perceptions of and responses to subtly discriminatory situations.

It is important to note that the strength and the salience of one’s social identity represent closely related yet conceptually distinct constructs (Ellemers, Spears, & Doosje, 1999; see also Oakes, Haslam, & Turner, 1994). Specifically, the strength of one’s social identity typically refers to the chronic accessibility (i.e., centrality or importance) of group membership in one’s self-concept. In contrast, the salience of one’s social identity is context dependent; one’s identity as a group member might become more or less subjectively meaningful relative to one’s identity as an individual person in response to subtle situational cues (Haslam, Oakes, Reynolds, & Turner, 1999). Thus, although people who are strongly identified with a particular social group are, in general, more likely to find their group identity salient in any given situation, the salience of one’s group identity, when contextually activated, can independently shape people’s thoughts and actions (Shih, Pittinsky, & Ambady, 1999; Steele & Aronson, 1995) and may do so in ways over and above effects of individual differences in strength of identification (Transue, 2007).

The literature on individual differences in group identification includes some important insights into how the salience of women’s gender identity can influence responses to sexism. In one study, for example, women higher in gender identification (those who endorse items such as “Being a woman is an important reflection of who I am”) were more likely to attribute a male evaluator’s negative feedback to prejudice when a confederate mentioned that the evaluator “tends to grade guys and girls differently,” compared with those who scored lower on gender identification (Major, Quinton, & Schmader, 2003). This general inclination to recognize discrimination when it occurs can promote actions to challenge its perpetrators. Indeed, research on collective action has demonstrated that, relative to individuals with weaker group identification, those who identify more with their disadvantaged group express stronger intentions to participate in organized social movements with other members of their group (e.g., initiating a petition or collective protest) to address their group-based disadvantage (see van Zomeren, Postmes, & Spears, 2008, for a review). Consistent with these findings, women who endorsed higher levels of gender identification also reported greater involvement in feminism-related activities than those who endorsed lower gender identification (Liss, Crawford, & Popp, 2004).

A separate line of research has also linked the strength of gender identification, often considered as a stable individual difference (Leach et al., 2008), to inclination to confront sexist behaviors. Two retrospective studies showed that women who were strongly identified with their gender group (Good, Moss-Racusin, & Sanchez, 2012), or who identified themselves as feminists (Ayres, Friedman, & Leaper, 2009), were more likely to report confronting past instances of sexism than their more weakly identified counterparts, regardless of the perceived efficacy of their actions and even when confrontation was perceived as relatively costly. However, retrospective report paradigms have some inherent limitations (Wheeler & Reis, 1991). Specifically, participants’ recollections of their past experiences and behaviors may not be entirely accurate; furthermore, women who are high in gender identification may selectively recall instances in which they confronted the perpetrators of discrimination.

The Present Study

In the present research, we extended previous work by examining the contextual antecedents of perceiving and confronting gender discrimination. According to both social identity theory and self-categorization theory, subtle, incidental cues within a social context can spontaneously prime and activate social or personal identity. Priming social identity, compared to personal identity, is more likely to increase sensitivity to incidents that threaten the esteem of one’s group and to motivate action against these threats. Drawing from these perspectives, the current study complements previous research on the relation between individual differences in gender identification and confrontation (e.g., Major et al., 2003); specifically, we considered how contextual cues that temporarily prime social or personal identity might influence women’s confrontation of a sexist incident.

To examine this possibility, we experimentally manipulated the salience of women’s gender versus personal identity, with the goal of assessing the independent causal impact of social identity salience on women’s prejudice perception and subsequent confrontation of gender bias in the context of a simulated online interaction. We operationalized confrontation as the extent to which participants expressed opposition to the views of their male interaction partner in their written responses (see Lee, Soto, Swim, & Bernstein, 2012, for a similar operationalization). Given that individuals’ perceptions of their own behaviors often differ from those of third-party observers (Pronin, 2009), we examined our hypotheses with respect to both participants’ perceptions of their own responses to the sexist comment (i.e., self-reported confrontation) and independent coders’ ratings of these responses (i.e., coded confrontation).

As noted earlier, according to social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; see also Abrams & Hogg, 2010), individuals whose social identity is made salient are more inclined to attribute unfair treatment to group-based injustice (i.e., prejudice and discrimination) and more willing to take actions to defend and enhance the status of their in-groups (van Zomeren et al., 2008). Building on this line of research as well as existing work on individual differences in the strength of gender identification (e.g., Good et al., 2012; Major et al., 2003), we hypothesized that participants who were primed to focus on their gender identity would be more likely to confront their interaction partner about making a sexist comment (in terms of both self-report and coders’ ratings) than those who were primed to focus on their personal identity (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, consistent with the idea that individuals must first recognize discrimination before they can actively address it (Ashburn-Nardo et al., 2008; Ellemers & Barreto, 2009), we hypothesized that the effect of gender identity salience on both self-reported and coded confrontation would be mediated by prejudice perceptions: Women whose gender identity was made salient would perceive the comment from their interaction partner as more prejudiced (Hypothesis 2A) and would in turn be more likely to respond by engaging in confrontation (Hypothesis 2B).

Method

Participants

A total of 119 participants living in the United States were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (Mturk.com). Mechanical Turk is an Internet-based platform that permits members of the general public to complete tasks anonymously in exchange for monetary compensation. In order to facilitate the collection of high-quality data, MTurk allows researchers to reject participants’ work if they do not follow instructions, and thus it serves as an inexpensive yet valid source of data for behavioral science researchers (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Mason & Sufi, 2010). In the current study, five participants, who started the survey but did not complete it, were excluded from analyses and the final sample consisted of 114 women. These participants ranged in ages from 18 to 65 years (M = 36.70, SD = 12.57). Most of the sample was White (n = 85), but 29 indicated other racial and ethnic identities (15 African American, 5 Latina, 4 Asian, and 5 other). Each participant was paid US$.75 upon completion of the study.

Procedure

Participants were told that the study was designed to examine factors shaping patterns of asynchronous communication on the Internet. At the beginning of the study, participants completed the gender or the personal identity salience manipulation adapted from Verkuyten and Hagendoorn (1998).

Experimental manipulation

We manipulated identity salience by randomly assigning participants to one of the two experimental conditions designed to activate the salience of either personal or gender identity. Specifically, participants were randomly assigned to complete a short measure of either personal or collective self-esteem. Although this manipulation may seem subtle, the stereotype threat literature has consistently shown that answering simple questions about one’s membership in a particular group can increase the salience of one’s identity in relation to that group, which can in turn lead to significant cognitive and behavioral consequences (e.g., Shih et al., 1999; Steele & Aronson, 1995; Wang & Dovidio, 2011).

Participants assigned to the personal identity condition were instructed to reflect on their general feelings about themselves as unique individuals and indicated their agreement with 7 items taken from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”; Rosenberg, 1965). Each item was rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree); the internal consistency for this sample was adequate, α = .88. Participants assigned to the gender identity condition were asked to reflect on their general feelings about themselves as members of their gender group and to indicate their agreement with 7 items taken from the Collective Self-Esteem Scale (e.g., “My gender identity is an important reflection of who I am”; Luhtanen & Crocker, 1992). Each item was also rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree); the internal consistency for this sample was adequate, α = .78. The specific instructions and items used in the gender identity salience manipulation are included in the Online Supplemental Materials.

Pilot testing of the experimental manipulation

To avoid sensitizing participants to the nature of the experimental manipulation, we did not include any explicit validity checks of the gender identity salience manipulation in the current study. However, to establish the validity of the manipulation of gender identity salience and to ensure that the manipulation would work as intended, we conducted a pilot study with an independent sample of women. Participants (N = 40) for the pilot study were also drawn from a national online participant pool. They ranged in ages from 19 to 65 (M = 39.80, SD = 15.21); most of the sample was White (n = 32), but eight indicated other racial/ethnic identities (two African American, two Latina, three Asian, and one other).

Based on previous research using the accessibility of words as a measure of salience (e.g., Gilbert & Hixon, 1991; Monteith, Sherman, & Devine, 1998) and specifically the paradigm of Hass and Eisenstadt (1990), we informed participants that they would be presented with a word subliminally and then instructed to identify what they saw by choosing between a pair of words. In reality, no stimuli were presented subliminally; rather, after viewing a blank mask, participants were asked to choose between a gender-related and a nongender-related word. A total of six word pairs were used: men versus mine, woman versus human, she versus self, he versus me, boy versus body, and her versus our. The number of gender-related words selected was calculated for each participant and served as a measure of gender identity salience. Participants also completed a 4-item measure of individual differences in gender identification adapted from Leach et al. (2008; e.g., “Being a woman is an important part of my self-image.”). All items were rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree); the Cronbach’s α in this sample was .83. As intended, the manipulation affected the salience of gender identity, operationalized as the accessibility of gender-related words, but not the strength of women’s gender identification, as measured by the adapted Leach et al. (2008) measure. Specifically, women who completed the gender Collective Self-Esteem Scale reported seeing more gender-related words than those who completed the Personal Self-Esteem Scale, Ms = 3.10 (SD = 1.45) versus 2.30 (SD = 0.91), t(38) = 2.07, p = .045, d = .66. Completing the collective versus the personal self-esteem scales did not affect the strength of gender identity, Ms = 5.14 (SD = 1.23) versus 5.61 (SD = 0.43), t(38) = 0.53, p = .60, d = .051. These findings support the validity of our manipulation of gender identity salience in the current study.

Online interaction

Immediately following completion of the gender identity salience experimental manipulation, participants in the current study engaged in an online interaction in which they were given an opportunity to respond to a scripted paragraph expressing sexist views allegedly written by a male communication partner. The online communication partner, who was named Michael, was described as a 30-year-old software engineer seeking advice about a problem at work. In reality, there was no communication partner; all participants read the following paragraph:

I’m a software engineer and have been with my current company for five years. For the most part, I have really enjoyed my job: The work is challenging and interesting, my colleagues are friendly, and the pay is quite decent. However, I have noticed a change at work that has been bothering me for the past year or two. There seems to be more and more young women entering the company, and many of them strike me as not very well-qualified. I understand that this is supposed to contribute to the diversity of our industry, but frankly I think that favoring women in the hiring process may be problematic. Given that women have historically under-performed in math and science, it is only natural that there are fewer women than men in the technology industry. As I start taking on more management responsibilities, I’m concerned about these new trends in hiring practices and wonder what they will do to the future of my company and my industry more generally. I would be really interested in hearing your thoughts about this issue.

Participants then had an opportunity to provide a written response to Michael. We assessed the extent to which they engaged in confrontation in two ways: via participant self-report and by coding participants’ written responses (see Measures section for more information). Participants also subsequently completed measures of perceived prejudice.

Measures

Self-reported confrontation

We assessed self-reported confrontation using a single item specifically created for the purpose of the current study. Participants rated their responses to Michael’s comment about women in the industry using a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (expressed strong support for Michael’s comment) to 7 (expressed strong objections to Michael’s comment). This bipolar scale was selected to capture both the valence of participants’ responses (i.e., whether they agree or disagree with Michael) and the intensity of their responses.

Coded confrontation

To assess how independent coders perceived the participants’ remarks in response to the male confederate’s comments, four independent judges unaware of the experimental conditions rated each of the written responses using the same 7-point scale that the participant used, that is, in terms of the degree to which the response expressed strong support for Michael’s comment (a rating of 1) to strong objections to Michael’s comment (a rating of 7). To help establish consensus in coding criteria, coders discussed their judgments for five practice trials. Following the procedure used by Lee, Soto, Swim, and Bernstein (2012), the coders independently rated each sample statement and then discussed the criteria (e.g., types of verbs, favorability of adjectives, and emotions expressed) determining their ratings. The independent ratings from the four judges for the actual responses in the study demonstrated strong interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = .96, Krippendorff’s α = .86) and were averaged to form a single measure. Table 1 presents the criteria used by the coders and provides a paraphrased sample statement for each coding category (note that paraphrased statements are presented because we informed participants that we would not share their verbatim responses during debriefing).

Table 1.

Coding Criteria and Sample Statements.

| Coding | Criterion | Paraphrased Sample Statement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Complete agreement with Michael’s comment | I completely agree. Factors like sex and race should never play a role in the hiring process. If there are more qualified male applicants in the industry, then that’s just the way things are. |

| 2 | Moderate (qualified) agreement with Michael’s comment | I understand where you are coming from, even though I’m a woman myself. However, there is not much you can do about the situation until a supervisor notices that the women aren’t performing well. That said, maybe you shouldn’t judge all women as unqualified. Try to view them on a case-by-case basis – Perhaps some of them are actually good workers! |

| 3 | Slight (qualified) agreement with Michael’s comment | I don’t think we should hire people on the basis of filling quotas, but it does happen. I would imagine that, if someone were really unqualified, they would have to be fired or demoted to a position they could handle. My only advice is to try to be as tolerant and open-minded as possible. If you continue to notice problems, then talk to the higher management. |

| 4 | Neutral or irrelevant response to Michael’s comment | Diversity in the workplace is a good thing, but only if employees have the proper experience and training to handle their positions. Maybe your company could start an apprentice program geared towards less qualified applicants? They would probably perform better and have more confidence with some additional training. |

| 5 | Slight (qualified) disagreement with Michael’s comment | What makes you think these women aren’t qualified? Could they perhaps just be approaching issues differently than you do? If they are getting hired without the right education that is a problem. But if they have the qualifications, their different approaches to issues can be valuable in the long run. |

| 6 | Moderate (qualified) disagreement with Michael’s comment | I’m sad that you feel that way. You need to take things on a case-by-case basis and give these women a chance. They are not all the same, and some might even out-perform you. Don’t be so judgmental! |

| 7 | Complete disagreement with Michael’s comment | It sounds like you are a sexist person. Maybe you should just focus on their skills instead of their gender. I’m sure some of your male co-workers are incompetent too. |

Perceived prejudice

To assess whether the identity salience manipulation affected how participants viewed the comments made by the male confederate, we presented participants with a quote from the paragraph allegedly written by Michael (“given that women have historically under-performed in math and science, it is only natural that there are fewer women than men in the technology industry”) and asked them to indicate the extent to which they perceived Michael’s remarks as prejudiced using 2 items: (a) “to what extent do you find Michael’s comment to be sexist?” and (b) “to what extent do you find Michael’s comment to be rude?” Each item was rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much), r(112) = .64, p < .001.

Other measures

The current research was part of a larger study examining women’s emotional and behavioral responses to sexism. For the larger study, in addition to the dependent measures described above, participants completed a number of measures regarding their habitual use of different emotion regulation strategies, including the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) and the Ruminative Responses Scale (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003), at baseline. In addition, they were asked to indicate their emotional responses to Michael’s comment using a subset of items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Because these scales were irrelevant to the main purpose of the current study and were not systematically related to our outcomes of interest, they are not discussed further. All of the experimental conditions in the present research are reported. No other publications or manuscripts have resulted from this data set.

Debriefing

After completing all measures in the study, participants were asked directly what they believed was the true purpose of the current research. Then, we fully debriefed each participant when she completed her individual study session. Specifically, we informed participants that the study was designed “to better understand how women decide whether to confront gender discrimination in a web-based context.” Participants learned that “the communication partner does not exist in reality; all the information you read was generated by the investigators, and your written responses will not be shared with anyone outside the research team.”

Results

Data Analytic Strategy

No participants were excluded because of suspicion; there was little spontaneous suspicion about Michael being an actual partner in the exchange or about the true purpose of the study. In response to the open-ended question about their reactions to Michael, only two participants mentioned the possibility that Michael might be “fabricated”; 85 made comments directly about Michael (e.g., “I told myself he was limited by his upbringing”), about how his comments affected them (e.g., “I told myself to stay calm in writing my response to Michael”), and/or about the strategy with which they formulated a response (e.g., “I thought this man is ignorant so tried to be nice in my response”). When asked directly what they thought the true purpose of the study was, 40 participants (13 in the personal identity condition and 27 in the gender identity condition) inferred that it was about sexism or gender discrimination. Even in response to this direct probe, which was administered after participants indicated the extent to which they found Michael’s comment to be prejudiced, no participant mentioned the experimental manipulation to make gender or personal identity salient nor did any identify the main research hypothesis. Nevertheless, given that a greater percentage of participants in the gender identity condition, relative to the personal identity condition, identified the general purpose of the study (i.e., sexism/gender discrimination), χ2(1, N = 114) = 4.85, p = .03, we repeated all subsequent analyses with general suspicion (dichotomized as 0 = did not identify study as related to sexism and 1 = identified study as related to sexism) as a covariate. We reported these additional analyses, which replicated the results of the main analyses, in the Online Supplemental Materials.

In all analyses, we treated both self-reported and coded confrontation as continuous variables, given that they were rated, similar to other measures in the study, on a 7-point scale. To check for potential covariates, we first examined the bivariate associations between demographic characteristics and both self-report and coded confrontation. Specifically, we calculated the Pearson correlation between age and confrontation. Due to the small number of participants within each racial and ethnic minority group, we dichotomized the variable into White (n = 85) and other racial and ethnic identities (n = 29) and compared confrontation responses between these two groups using an independent samples t-test. To ensure that participants’ inclination to engage in confrontation did not vary systematically as a function of personal or collective self-esteem within each experimental condition, we further assessed the correlations between personal (collective) self-esteem and confrontation. Following these analyses, we conducted two separate univariate analyses of variance to examine the role of gender identity salience in predicting both self-report and coded confrontation (Hypothesis 1). Last, we utilized the indirect SPSS macro designed by Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes (2007) to test the idea that perceived prejudice would mediate the effect of gender identity salience on confrontation (Hypothesis 2).

In preliminary analyses, participant age was not significantly associated with either self-reported, r(112) =−.07, p = .47, or coded confrontation, r(112) = .06, p = .54. Similarly, there was no significant between-group difference across White participants and participants with other racial and ethnic identities with respect to self-reported, t(112) =−1.33, p = .19, and coded confrontation, t(112) = −.57, p = .57. Thus, these variables were not considered in all subsequent analyses. Furthermore, within each experimental condition, self-reported and coded confrontation did not systematically vary as a function of personal, r(51) = −.25, p = .07, or collective self-esteem, r(59) = .19, p = .16.

Effect of Gender Identity Salience Manipulation on Confrontation

We tested Hypothesis 1 by examining the effect of gender identity salience on both self-reported and coded confrontation, which were strongly correlated with each other, r(112) = .76, p < .001. As revealed by separate univariate analyses, the effect of identity condition was significant for self-reported confrontation, F(1, 112) = 5.31, p = .02, , but not for coders’ ratings of confrontation, F(1, 112) = 3.49, p = .06, . In light of these discrepant results, we conducted a profile analysis (also known as a test of parallelism; Bray & Maxwell, 1985), in which we treated the two confrontation measures as a two-level repeated measures factor. The Identity Condition × Measure interaction was not significant, F(1, 112) = 0.13, p = .72, indicating that self-reported and coded confrontation were commensurate (i.e., effect of the experimental manipulation did not significantly diverge across measures). Furthermore, supporting Hypothesis 1, the effect of the identity condition was significant across confrontation measures, F(1, 112) = 4.96, p = .03.

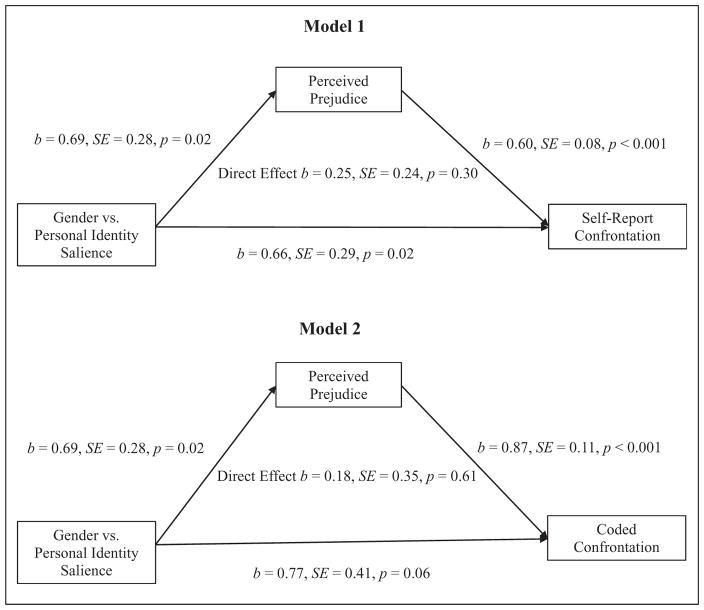

We then tested Hypothesis 2 by conducting two separate mediation analyses, with self-reported and coded confrontation as respective dependent variables. Participants’ perceived prejudice correlated significantly with both self-reported confrontation, r(112) = .61, p < .001, and coded confrontation, r(112) = .60, p < .001. As illustrated in the top panel of Figure 1, consistent with the idea that priming women with their gender identity would elicit heightened vigilance for cues of bias (Hypothesis 2A), participants assigned to the gender identity condition perceived Michael’s comment as more prejudiced than those assigned to the personal identity condition, b = .69, SE = .28, t(112) = 2.45, p = .02. With respect to self-reported confrontation ratings, consistent with Hypothesis 2B, perceived prejudice was significantly associated with confrontation, b = .60, SE = .08, t(112) = 7.64, p < .001. Furthermore, the effect of gender identity salience on confrontation was significantly mediated by participants’ perceived level of prejudice: The 95% confidence interval for the indirect path from the gender identity condition to self-reported confrontation through perceived prejudice ranged from 0.09 to 0.84 and did not include zero. A similar pattern of results, presented in the bottom panel of Figure 1, was replicated with respect to coders’ ratings of confrontation behavior. Participants’ level of perceived prejudice was again associated with confrontation, b =.87, SE = .11, t(112) = 7.65, p < .001. In addition, perceived prejudice emerged as a significant mediator: The 95% confidence interval for the indirect path from the gender identity condition to coded confrontation through perceived prejudice ranged from 0.14 to 1.19 and did not include zero.

Figure 1.

Effect of gender versus personal identity salience on confrontation through perceived prejudice.

We also examined the possibility that participants’ confrontation behavior would mediate the effect of gender identity salience on perceived prejudice. Given that coded confrontation did not significantly differ across experimental conditions (p = .06), we only tested this alternative mediation model with respect to self-reported confrontation. Participants assigned to the gender identity condition were more likely to confront the sexist comment than those in the personal identity condition, b = .66, SE = .29, t(112) = 2.30, p = .02. Furthermore, self-reported confrontation was significantly associated with perceived prejudice, b = .58, SE = .08, t(112) = 6.64, p < .001. Self-reported confrontation emerged as a significant mediator: The 95% confidence interval, ranging from 0.07 to 0.81, did not include zero.

Discussion

In the present research, we examined the effect of experimentally manipulated gender identity salience on women’s tendency to perceive and confront sexism. We found that, consistent with the basic tenets of social identity and self-categorization theory, women who were primed to focus on their gender identity perceived a subtly sexist comment from a male interaction partner as more prejudiced than those who were primed to focus on their personal identity and were more likely to respond by engaging in confrontation. While existing work has consistently linked dispositional individual differences in gender identification to both discriminatory attributions and confrontation behaviors (Good et al., 2012; Major et al., 2003), in the current study, we extended previous research by demonstrating that even increasing the salience of women’s gender identity temporarily through subtle contextual cues can play a powerful role in shaping individuals’ perceptions of and responses to potentially discriminatory situations. In light of earlier retrospective, correlational studies, in which women who more strongly identified with their gender group (Good et al., 2012), or who identified themselves as feminists (Ayres et al., 2009), were more likely to report confronting past instances of sexism; the present study represents a significant contribution to the literature by demonstrating the causal impact of gender identity salience on women’s thoughts and behaviors in response to a specific sexist incident.

Although the indirect effect of identity salience on confrontation through perceptions of prejudice was significant for both participants’ and coders’ ratings, the size of the effects was modest (in the range of r = .20). Nevertheless, in the context of experiencing or addressing bias, even statistically small effects can have significant social consequences by cumulatively shaping the behaviors of a large number of individuals over time (Greenwald, Banaji, & Nosek, 2015; Martell, Lane, & Emrich, 1996). In addition, we note that the direct effect of identity salience on confrontation was stronger for participants’ self-report assessments than for coders’ ratings. As noted by Pronin (2009), people tend to rely more on introspective information (i.e., how they think and feel) when assessing their own behaviors but focus more on the actual actions being carried out when assessing others’ behaviors. Therefore, it is likely that participants, having access to their own goals and intentions, produced ratings that, compared to those of independent coders, were more reflective of their intentions to confront sexism than evident in their actual behavior.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

We acknowledge that certain characteristics specific to the current interaction paradigm might have facilitated our participants’ confrontation behavior. First, for the purpose of maintaining the flow of the interaction, participants were explicitly invited by their communication partner to comment on the issue being discussed (i.e., diversity initiatives designed to increase women’s representation in the technology industry). This invitation provided a clear indication to participants that it was their turn to communicate, which presented a well-defined opportunity for responding to the sexist comment rarely found in everyday interactions (see also Rattan & Dweck, 2010, for the use of a similar paradigm). Second, because participants knew little about their interaction partner and did not expect to interact with him in the future, confrontation carried relatively low interpersonal costs. This interpretation is consistent with the observation that 67% of the participants engaged in confrontation to some extent, which is much greater than the rates observed in previous research documenting targets’ general reluctance to confront when they are placed in actual discriminatory situations (Swim & Hyers, 1999; Woodzicka & LaFrance, 2001). Third, whereas face-to-face interaction paradigms typically examine spontaneous responses to sexist statements, our asynchronous computer-mediated interaction allowed time for participants to reflect on the comment and prepare a response (see also Rasinski, Geers, & Czopp, 2013). As a result, the responses of our female participants were likely to be more deliberative and therefore may not directly reflect their spontaneous reactions to a similar sexist comment in more immediate interactive settings (Fazio & Olson, 2014).

Although our findings may not generalize directly to confrontation that occurs spontaneously in face-to-face interactions, the current asynchronous written communication paradigm does have relevance to naturalistic forms of social behavior, given the popularity of blogs, tweets, and other forms of electronically mediated communication in which interactants may not be personally identifiable to one another. For example, blogs, which typically allow readers to submit comments anonymously, attract 300% more views and 233% more visitors than conventional online articles on the same topic (Greenslade, 2012). Similarly, over 100 million people use Twitter (Hatchman, 2011), which has become one of the most popular forms of communication among adolescents (Greig, 2013). Thus, confrontation of sexism in the context of asynchronous, anonymous, electronically mediated communication merits study in its own right, not only because of its increasing social significance, but also because it may offer valuable theoretical insights into the dynamics of confronting sexism across different situations.

It is also worth noting that, in order to capture women’s confrontation behavior in a naturalistic way (and as in previous work on prejudice confrontation; see Lee et al., 2012), we collected participants’ written responses to the sexist comment before assessing their prejudice perceptions. This choice of measurement order was made primarily for practical considerations: Assessing how prejudiced the comment was perceived to be, before allowing participants to respond to the sexist comment, would likely make the purpose of the research entirely transparent and subject their responses to experimenter demand. Our current interpretation, that perceptions of prejudice mediated the impact of gender identity salience on confrontation, is grounded in previous work demonstrating the role of discriminatory attributions as an important antecedent of confrontation (Ashburn-Nardo et al., 2008). However, it is also conceivable that, upon reflecting on a stronger confrontation response, participants might have rated the instigating remark as more prejudiced in order to justify their actions. Although this possibility appeared to be supported by our alternative mediation model, with respect to self-reported confrontation, inherent limitations of statistical mediation precluded us from determining the direction of causality between perceived prejudice and confrontation, given the current study design (Spencer, Zanna, & Fong, 2005). Thus, it will be important for future researchers to ascertain the causal links among gender identity salience, perceptions of sexism, and confrontation behavior by manipulating the extent people may perceive a comment as prejudiced (e.g., by introducing information that another person views the comment as biased or unbiased; Sechrist & Stangor, 2001).

We further note that, consistent with previous studies that utilized similar paradigms to study prejudice confrontation (Lee et al., 2012; Rattan & Dweck, 2010), we used measures of both perceived prejudice and self-reported confrontation that were only 1 or 2 items; we wanted to minimize participants’ burden and obscure the study’s focus on confrontation. To improve the validity of our findings, we supplemented the single-item measure of self-reported confrontation with coders’ ratings of participants’ written responses. Nonetheless, future researchers might more reliably assess these constructs and use well-validated measures.

The present research also raises a number of other interesting questions worthy of future research. Given that the current study included only two experimental conditions in which participants were primed with either their personal or gender identity, and did not include a no-prime control group, we cannot be certain of the direction of the experimental manipulation’s effect. Although our interpretation that gender identity salience increased women’s willingness to confront gender discrimination is well grounded in the theoretical literature (e.g., Good et al., 2012; Major et al., 2003), it is also possible that priming women with their personal identity would reduce their willingness to confront sexist messages by increasing the sense of individuation and making women feel “singled out.” Indeed, people are more likely to conform to the expectations of others, and are more sensitive to the social costs for deviating from those expectations, when they feel more personally identifiable; by contrast, when social identity is salient, people conform more strongly to the norms and expectations of members of that social group (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Postmes & Spears, 1998). Future researchers could disentangle the facilitating effect of salient gender identity or the inhibiting influence of salient personal identity by adding a control condition in which female participants do not answer any identity-related questions prior to the simulated online interaction.

Although previous research has linked the strength of gender identification to women’s inclination to confront sexist behaviors (Ayres et al., 2009; Good et al., 2012), in the current study, collective self-esteem was positively, though not significantly, associated with confrontation. This discrepancy might be attributable to our lack of statistical power, given that only those participants who were assigned to the gender identity condition (n = 61) completed the collective self-esteem measure. Furthermore, it is possible that the collective self-esteem items used in the current study, which assessed the importance of gender identity to one’s self-concept, did not capture components of gender identification that are most closely related to prejudice confrontation. Indeed, previous research linking gender identification to confrontation has utilized measures that assessed constructs such as solidarity (Good et al., 2012) and feminist ideology (Ayres et al., 2009), which represent activist orientations. Given the multifaceted nature of in-group identification (Leach et al., 2008), future researchers could further investigate how various components of gender identification might differentially facilitate confrontation of sexism.

Future research might also directly investigate how the influence of gender identity salience may be moderated by contextual factors, such as nature of the sexist event itself. In the present research, we presented participants with a sexist but subtle comment, with the goal of eliciting significant individual variations in confrontation. Because exposure to blatant sexism, relative to subtle sexism, tends to produce more uniform recognition of unfair bias and relatively high levels of collective action tendencies with more limited variability of response (Wang, Stroebe, & Dovidio, 2012), presenting participants with a more blatantly sexist comment would likely induce high levels of confrontation in both the personal identity and gender identity conditions, thereby reducing the difference between these conditions.

Last, while the present research considered perceived prejudice as a mediator underlying the impact of gender identity salience on confrontation, the collective action literature has identified a number of other potential mechanisms, such as feelings of solidarity with other group members and perceived efficacy of one’s actions (see van Zomeren et al., 2008, for a review). Indeed, it is likely that activating a woman’s gender identity would increase her sense of connectedness with other women (i.e., sisterhood) and therefore prompt her to confront a sexist remark that threatens her gender group. Consideration of these mediators in future research could help further clarify the paths through which gender identity salience operates to influence confrontation.

Practice Implications

The current study highlights the role of gender identity salience in the context of responding to subtle forms of sexism. While previous research on stereotype threat has shown that priming women with their gender identity can lead to a wide range of negative outcomes, such as decreased performance in stereotyped academic domains (Quinn, Kallen, & Spencer, 2010; Shih et al., 1999; Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999), our results showed that doing so might have adaptive consequences under certain circumstances. Specifically, when women are placed in relatively “safe” situations where asserting their rights comes with few social costs, the salience of their gender identity might prompt the recognition of subtle sexist comments, thereby facilitating interpersonal confrontation and social change (Mallett & Wagner, 2011). In addition, confrontation under these circumstances represents an active coping strategy that increases a sense of personal and collective empowerment and control (Gervais et al., 2010), with benefits to both psychological and physical health (Greenaway et al., 2015). These effects are especially relevant in contemporary society, in which many instances of sexism are subtle and therefore difficult to recognize and actively address (Ellemers & Barreto, 2009).

Our findings have important implications for professionals designing diversity training initiatives in both higher education and workplace settings. Whereas many current interventions focus on enhancing a sense of belongingness in socially disadvantaged group members by encouraging them to find common ground with their majority peers (Dovidio, Gaertner, Ufkes, Saguy, & Pearson, 2016; Walton & Cohen, 2007; Yeager & Walton, 2011), programs that instead emphasize the acknowledgment of potential discrimination and active ways of coping with bias can represent a complementary approach. Rather than directly attempting to change the extent to which women personally identify with their gender group, programs could help women activate their gender (rather than personal) identity in the context of subtle bias and equip them with the necessary tools to evaluate the social costs and benefits associated with active confrontation in these situations. Such interventions would enable women to make context-sensitive decisions in terms of the best way to respond to subtle discrimination directed toward them or other women. In sum, given the value of confrontation as an active coping strategy with psychological benefits and an effective means to promote social change, our results suggest that gender identity salience can be an important motivator for women who continue to navigate instances of subtle sexism in their everyday lives.

Conclusions

In the present research, we examined the causal impact of gender identity salience on prejudice confrontation by using an experimental manipulation derived from self-categorization theory. While the salience of one’s personal versus social identity has received much attention in the collective action literature, especially as it relates to individuals’ affective responses to group-based injustice and the perceived efficacy of their attempts to address such disadvantage (van Zomeren et al., 2008), much less work has addressed the effects of social identity in the context of interpersonal prejudice confrontation. By investigating the impact of identity salience on confrontation in the context of a novel paradigm, the current study significantly contributed to the existing literature on the dynamics of perceiving and responding to gender discrimination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Preparation of this manuscript was supported by U.S. Public Health Services grants T32MH020031 and 3R01MH109413-S1 awarded to Katie Wang.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health. Any underlying research materials for this study, including the data on which the current analyses were based, can be obtained by e-mailing the corresponding author.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abrams D, Hogg MA. Social identity and self-categorization. In: Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, Esses VM, editors. Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination. London, England: Sage; 2010. pp. 179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams D, Thomas J, Hogg MA. Numerical distinctiveness, social identity and gender salience. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1990;29:87–92. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1990.tb00889.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburn-Nardo L, Morris KA, Goodwin SA. The Confronting Prejudiced Responses (CPR) model: Applying CPR in organizations. Academy of Management. 2008;7:332–342. doi: 10.5465/AMLE.2008.34251671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres MM, Friedman CK, Leaper C. Individual and situational factors related to young women’s likelihood of confronting sexism in their everyday lives. Sex Roles. 2009;61:449–460. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9635-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray JH, Maxwell SE. Multivariate analysis of variance. Vol. 54. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:591–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, Ufkes EG, Saguy T, Pearson AR. Included but invisible? Subtle bias, common identity, and the darker side of “we. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2016;10:4–44. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers N, Barreto M. Collective action in modern times: How modern expressions of prejudice prevent collective action. Journal of Social Issues. 2009;65:749–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01621.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers N, Spears R, Doosje B, editors. Social identity. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio RH, Olson MA. The MODE model: Attitude-behavior processes as a function of motivation and opportunity. In: Sherman JW, Gawronski B, Trope Y, editors. Dual-process theories of the social mind. New York, NY: Guilford; 2014. pp. 155–171. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais SJ, Hillard AL, Vescio TK. Confronting sexism: The role of relationship orientation and gender. Sex Roles. 2010;63:463–474. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9838-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT, Hixon JG. The trouble of thinking: Activation and application of stereotypic beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:509–517. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Good JJ, Moss-Racusin CA, Sanchez DT. When do we confront? Perceptions of costs and benefits predict confronting discrimination on behalf of the self and others. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2012;36:210–226. doi: 10.1177/0361684312440958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenaway KH, Haslam SA, Cruwys T, Branscombe NR, Ysseldyk R, Heldreth C. From “we” to “me”: Group identification enhances perceived personal control with consequences for health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2015;109:53–74. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenslade R. Research reveals popularity of life blogging. The Guardian. 2012 Nov 20; Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/media/greenslade/2012/nov/20/blogging-cityuniversity.

- Greenwald AG, Banaji MR, Nosek BA. Statistically small effects of the implicit Association Test can have societally large effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2015;108:553–561. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig A. Twitter overtakes Facebook as the most popular social network for teens, according to study. Daily Mail Online. 2013 Oct 24; Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2475591/Twitter-overtakes-Facebook-popular-social-network-teens-according-study.html.

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam SA, Oakes PJ, Reynolds KJ, Turner JC. Social identity salience and the emergence of stereotype consensus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:809–818. doi: 10.1177/0146167299025007004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hass RG, Eisenstadt D. The effects of self-focused attention on perspective-taking and anxiety. Anxiety Research. 1990;2:165–176. doi: 10.1080/08917779008249334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchman M. Twitter continues to soar in popularity, site’s numbers reveal. PC Magazine. 2011 Sep 8; Retrieved from http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2392658,00.asp.

- Kaiser CR, Major B. A social psychological perspective on perceiving and reporting discrimination. Law and Social Inquiry. 2006;31:801–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4469.2006.00036.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser CR, Miller CT. A stress and coping perspective on confronting sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:168–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00133.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leach CW, van Zomeren M, Zebel S, Viek MLW, Pennekamp SF, Doosje B, … Spears R. Group-level self-definition and self-investment: A hierarchical (multi-component) model of in-group identification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:144–165. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EA, Soto JA, Swim JK, Bernstein MJ. Bitter reproach or sweet revenge: Cultural differences in response to racism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2012;38:920–932. doi: 10.1177/0146167212440292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss M, Crawford M, Popp D. Predictors and correlates of collective action. Sex Roles. 2004;50:771–779. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.0000029096.90835.3f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luhtanen R, Crocker J. A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18:302–318. doi: 10.1177/0146167292183006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Quinton WJ, Schmader T. Attributions to discrimination and self-esteem: Impact of group identification and situational ambiguity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2003;39:220–231. doi: 10.1016/50022-1031(02)00547-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett RK, Wagner DE. The unexpectedly positive consequences of confronting sexism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2011;47:215–220. doi: 10.1016/jjesp.2010.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martell RF, Lane DM, Emrich CE. Male-female differences: A computer simulation. American Psychologist. 1996;51:157–158. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W, Sufi S. Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods. 2010;5:411–419. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteith MJ, Sherman JW, Devine PG. Suppression as a stereotype control strategy. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:63–82. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes PJ, Haslam SA, Turner JC. Stereotyping and social reality. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Postmes T, Spears R. Deindividuation and anti-normative behavior: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;123:238–259. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.123.3.238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronin E. The introspection illusion. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 41. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, Kallen RW, Spencer SJ. Stereotype threat. In: Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, Esses VM, editors. Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination. London, England: Sage; 2010. pp. 379–409. [Google Scholar]

- Rasinski HM, Geers AL, Czopp AM. “I guess what he said wasn’t that bad”: Dissonance in non-confronting targets of prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2013;39:856–869. doi: 10.1177/0146167213484769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattan A, Dweck CS. Who confronts prejudice? The role of implicit theories in the motivation to confront prejudice. Psychological Science. 2010;21:952–959. doi: 10.1177/0956797610374740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Sechrist GB, Stangor C. Perceived consensus influences intergroup behavior and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:645–654. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih M, Pittinsky TL, Ambady N. Stereotype susceptibility: Identity salience and shifts in quantitative performance. Psychological Science. 1999;10:80–83. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SJ, Steele CM, Quinn DM. Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1999;35:4–28. doi: 10.1006/jesp.1998.1373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SJ, Zanna MP, Fong GT. Establishing a causal chain: Why experiments are often more effective than mediational analyses in examining psychological processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:845–851. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African-Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:797–811. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swim JK, Hyers LL. Excuse me—What did you just say?!: Women’s public and private responses to sexist remarks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1999;35:68–88. doi: 10.1006/jesp.1998.1370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swim JK, Hyers LL, Cohen LL, Ferguson MJ. Everyday sexism: Evidence for its incidence, nature, and psychological impact from three diary studies. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:31–53. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin WG, Worchel S, editors. The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1979. pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Transue JE. Identity salience, identity acceptance, and racial policy attitudes: American national identity as an uniting force. American Journal of Political Science. 2007;51:78–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00238.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:247–259. doi: 10.1023/A:1023910315561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- van Zomeren M, Postmes T, Spears R. Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;4:504–535. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten M, Hagendoorn L. Prejudice and self-categorization: The variable role of authoritarianism and in-group stereotypes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:99–110. doi: 10.1177/0146167298241008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, Cohen GL. A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:82–96. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Dovidio JF. Disability and autonomy: Priming alternative identities. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2011;56:123–127. doi: 10.1037/a0023039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Stroebe K, Dovidio JF. Stigma consciousness and prejudice ambiguity: Can it be adaptive to perceive the world as biased? Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;53:241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark L, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler L, Reis HT. Self-recording of everyday life events: Origins, types, and uses. Journal of Personality. 1991;59:339–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00252.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodzicka JA, LaFrance M. Real versus imagined gender harassment. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:15–30. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Walton GM. Social-psychological interventions in education: They’re not magic. Review of Educational Research. 2011;81:267–301. doi: 10.3102/0034654311405999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.